Overview

Since its launch in 2004, the open-access, peer-reviewed journal Southern Spaces has combined multimedia scholarly publishing with critical regional studies and graduate student training. This retrospective, conducted 2016–2017 and updated periodically, features recollections and commentaries from the journal’s founders and past members of the editorial staff. While conveying some of the highlights, milestones, and challenges, this is a partial history of Southern Spaces in every sense—abridged for length, incomplete, and told with a slant.

Participants: Southern Spaces’s co-founders Martin Halbert, Katherine Skinner, and Allen Tullos (senior editor); former managing editors Sarah Toton, Frances (Franky) Abbott, Katie Rawson, Jesse P. Karlsberg, and Meredith Doster; former series editor Mary Battle; and former Emory Center for Digital Scholarship projects coordinator Sarah Melton.

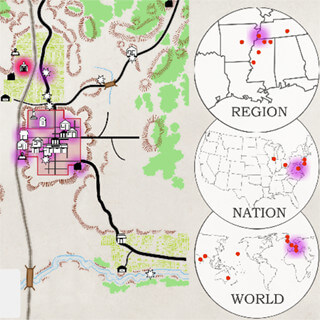

1926 Pharus Map of Berlin, Andrew Battista’s "Spatial Humanities and Modes of Resistance: a Review of Hypercities," September 15, 2015. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Beginnings

How did you become involved with Southern Spaces?

Halbert: I was involved in the inception of Southern Spaces and can shed some light on the endeavors that led to the creation of this marvelous and innovative new vehicle for scholarly communication. A fascinating and unpredictable journey through accidents and sagacity took us to what we needed.

During the early 2000s, I was Director for Digital Programs and Systems at Emory University Libraries while also pursuing my interdisciplinary PhD in Emory's Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts (ILA). Following my experience and training as a librarian and a technologist (at IBM and Rice University), I wanted to explore what the internet could mean for humanistic inquiry. How could the library and the systems department work more closely with scholars? The story of Southern Spaces began with an initiative seemingly unrelated to creating a journal, but without the initial support for graduate students, faculty travel, and technical assistance, Southern Spaces would not have happened. In retrospect it's very surprising, if not a small miracle, that the support became available for this work at all.

In 2001 the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation funded a series of projects on "metadata harvesting."1Martin Halbert, ed., Workshop on Applications of Metadata Harvesting in Scholarly Portals, MetaScholar Initiative, October 24, 2003, Emory University General Libraries. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277283794_Workshop_on_Applications_of_Metadata_Harvesting_in_Scholarly_Portals_Findings_from_the_MetaScholar. I was the principal investigator for two of these (the MetaArchive and AmericanSouth), which brought in some six hundred thousand dollars to the Emory Libraries. These grants inaugurated a new era of work for digital library activities at Emory which, I am gratified to say, have greatly expanded.

Without delving too deeply into these two projects, I'll share a few salient points. According to Mellon program officer Don Waters, the general idea of the initiative was to "explore the requirements for developing scholarly-oriented portal services based on the use of a variety of internet technologies, including the new Metadata Harvesting Protocol." 2Donald J. Waters, "The Metadata Harvesting Initiative of the Mellon Foundation," ARL: A Bimonthly Report, no. 217 (August 2001): 10–11. arl.org/storage/documents/publications/arl-br-217.pdf.

While other institutions in this initiative devoted their project work to narrowly defined technical development of software systems designed to use the metadata harvesting telecommunications protocol, I thought that these grant-funded projects should not build technical systems in isolation, but should explore digital innovations through collaborative relationships between the library and scholars. I sought to make MetaArchive and AmericanSouth such a broadly conceived program. I talked with interdisciplinary faculty and, whenever possible, hired bright project personnel who were themselves scholars.

I was interested in how media innovations affect the way we think about scholarly communication—in my doctoral research I studied media history scholars such as Walter Ong, Eric Havelock, and Harold Innis. I labeled this combination of projects the MetaScholar Initiative, and tried to get everyone involved to think both broadly and reflectively about the opportunities that new digital technologies offered. I was very fortunate in meeting people like Allen Tullos (who became my close collaborator and dissertation advisor), Katherine Skinner (my ally in many subsequent endeavors) and a number of ILA graduate students.

Skinner: I was part of the picture when SouthernSpaces.org germinated, gelled, and launched. I worked as its founding managing editor from 2003–2007, and I supervised subsequent managing editors until 2009, when I transitioned into my current role on the journal's editorial board.

Allen Tullos, Charles Regan Wilson, Will Thomas, Lucinda MacKethan, and Carole Merritt made up the scholarly design team for the AmericanSouth project that was led by Martin and on which I served as project manager. We were studying how to unite materials from disparate archives around a specific topical area—the study of the US South—using the internet and the bridging device protocol OAI-PMH (Open Archives Initiative-Protocol for Metadata Harvesting).

As we worked together on this project, Allen (who was also my dissertation director) suggested that primary source materials could be complemented by the creation of an online vehicle for scholarship. From our first conversations about founding a site for scholarly publication, Allen, Martin, and I agreed that we needed to demonstrate how the online environment could not only disseminate text-based digital scholarship, but could create and express new forms. We wanted to advance scholarship that used digital media as essential components.

We also wanted to differentiate the purpose of this new publication from "Southern Studies" in general, which considered "the South" as a monolithic historical and cultural entity. We wanted to examine the plurality of "souths" that existed and overlapped. We prioritized peer-reviewed scholarship that relied on multimedia elements, not just as reference points of cited works supporting an argument, but as part of the scholarship itself.3Charles Reagan Wilson, "A Scholar's Perspective on AmericanSouth.Org," in Halbert, ed., Workshop on Applications of Metadata Harvesting in Scholarly Portals.

Tullos: In terms of editorial perspective, Southern Spaces emerged from spatial theory (Henri Lefebvre), critical regional studies (David Harvey, Doreen Massey, Dolores Hayden), social justice theory (Iris Marion Young), cultural studies (Raymond Williams), and documentary practice. As Katherine Skinner mentions, one of our intentions was to critique broad, mystifying conceptions of the South—"Southern" imaginaries. Who needs or shapes a South and why? Why do simplistic and oppressive meanings of the South manage to live on into the twenty-first century? In such a South, it's always the day after yesterday. What can we gain by understanding the South not as a region, but as a geography of many changing regions and places?

We developed and solicited content about these southern regions (old, recent, and emerging), and about real and imagined places. We sought analysis that made conections from these locales to the wider world. And we aimed for an audience of scholars and teachers, students in and out of classrooms, writers and media producers, and the general public.

We wanted to distinguish Southern Spaces from strictly disciplinary publications and from just-the-facts online projects such as Wikipedia—invaluable though these are. As I assumed the role of senior editor, the scholarly design team transformed into a very active editorial board with the addition of Barbara Ellen Smith, Tom Rankin, Natasha Trethewey, and Earl Lewis—each contributing distinctive perspectives and talents.4See "About," at http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/. Early on, we featured essays offering interpretations of regions such as the Mississippi Delta, Black Belt, Carolina Piedmont, South Louisiana, metro Atlanta, and the Valley of Virginia. As a field project, we began the "Poets in Place" series (supported by an award from the Emory provost's office) collaborating with Natasha Trethewey to identify and video-record poets reading and commenting on their poems in the places they write about.

Southern Spaces built upon and extended a network of writers and scholars developed from my experiences as editor (1982–2003) of the print journal Southern Changes and from contacts suggested by our editorial board. We set up rights and permissions so that copyright of articles, images, videos, etc., remained with content creators. We depended on the networked infrastructure offered by the Emory Libraries (thanks to Martin and to library director Linda Matthews), and learned about organizing and describing materials from the library's subject area and metadata specialists. We decided, early on, that Southern Spaces would become a site for training graduate students in digital publishing. And that, where possible, we would collaborate with small non-profit organizations engaged in regional research and education that might not have access to their own publishing platforms.

Toton: I came to Emory in the fall of 2003 as a graduate student in American Studies from the University of Iowa. As a research assistant for Prof. Tullos I first transcribed OCR text into XML for the digital archiving of the journal Southern Changes. In January 2004 I began with Southern Spaces where I advanced from editorial associate to photo and media editor, then assistant managing editor, and finally managing editor before becoming a digital strategist at Emory Libraries in 2009. I left Emory to work as a technical product manager in digital media for Turner Broadcasting in 2010.

Abbott: I started working on Southern Spaces as a research assistant for Dr. Tullos during the 2006–2007 school year. I was an editorial associate in the summer of 2007, assistant managing editor from fall 2007 until August 2009, and managing editor from September 2009 until August 2011.

Battle: I began working as a graduate assistant for Southern Spaces in fall 2007, became a part-time, student employee in the summer of 2008, and served as an editorial associate and series editor until December 2010, when I moved to Charleston, South Carolina, to finish researching and writing my dissertation.

Rawson: I came to Emory to continue studying culture in the US South, and I had a background in editing literary journals and producing video, so I knew I wanted to be part of Southern Spaces. I initially tried to volunteer my time; however, the journal has an admirable policy of not having students work for free. Luckily, it didn't take long for then-managing-editor Sarah Toton to find the needed funding to add another position. I joined Southern Spaces as an editorial associate in the summer of 2008. From 2011 to 2013, I was the managing editor.

Melton: When I applied to Emory after my master's program in American Studies at the University of Alabama, I knew that I wanted to work on Southern Spaces. As part of my first-year graduate training for the ILA in 2009, I began as an editorial associate. I continued working on the journal for the next few years, becoming a series editor and assistant managing editor. In 2014, I transitioned into a full-time position at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS) where I continued to support the journal and other projects as a digital publishing strategist.

Karlsberg: I joined Southern Spaces in January 2011 as an editorial associate while serving as Allen Tullos's research assistant. I worked as assistant managing editor from 2012–2013 before becoming managing editor. Two years later I transitioned to a new role as consulting editor in which I help with strategy and technology concerns. I was especially involved in the migration of the journal from its Drupal 6 platform to Drupal 7 in 2015.

Doster: I came on staff in January 2013, transitioning to assistant managing editor in spring 2014. In August 2015, I stepped into the managing editor position, just in time to shepherd the final stages of the journal's migration to Drupal 7 to completion. My main emphasis as managing editor was the sustainability of journal staffing and training with lofty goals of coordinating and implementing a five-year strategic plan.

What was Southern Spaces like when you began working with it? How did it change with your participation?

Halbert: Of course, there was no journal when we started these projects and that wasn't what we thought we were creating. We began with concepts of "annotation," as in annotating archival records and web information discovered in a search and retrieval system. We set out to build "portals." Nowadays you would simply say we were creating websites. And, we built an array of them that did many things. But from discussions with scholars about what would be useful to them, one point kept emerging. While the basic assumption of the projects was that we needed to create systems for researchers to discover existing scholarly information, what scholars really wanted was a means of publishing new work. Everyone had been drowning in information for a long time. We didn't need to drink from a bigger fire hose. What people wanted was a way to make sense of information. Although I was obligated to finish the metadata portal work we had proposed, it was clearly Southern Spaces that became the single most compelling outcome of the projects.

It is always a surprise when you embark on a journey of discovery seeking one thing, and instead come upon something completely different. I thought this was a wonderful and wholly delightful outcome. While Southern Spaces now counts its start as 2004, we were debating the first questions associated with the idea of web-based scholarly publications as early as the 2002 meetings I convened at Emory. We discussed and planned the journal through 2003. Mellon continued to fund the metadata harvesting work with subsequent awards, but Southern Spaces grew in relative importance until it was the project.

Skinner: There was no "journal" in the beginning and we contested and debated the use of that term internally. We wanted relevance that stretched beyond the readers of traditional scholarly publications. Atlanta-based Mindpower Inc., where I'd worked prior to graduate school, produced the earliest design for Southern Spaces: sage green and orange, with a compass in the logo. We produced the site in Dreamweaver—which was a great way for non-coders to build. As the primary "keeper of the code," I produced the initial Southern Spaces publications by hand, using the coding view in Dreamweaver. I tried to code it all in xhtml. As we brought on additional students to help—Sarah Toton, Steve Bransford, Paul O'Grady, Jere Alexander, and Zeb Baker—we refined our methods. We hoped to provide a model that others could adapt.

Tullos: During our first year we were able to model most of content types that came to characterize the journal going forward: text essays that included hyperlinks, images, and maps; videos of poets in place; multi-media surveys of musical genres; media-illustrated lectures and edited conference presentations; interpretive overviews of regions and literary genres.

Not only did we create an excellent and active editorial board, we began to build a network of editorial reviewers to carry out scholarly evaluations of submissions. This network has grown over the years to include many peer reviewers in the US and beyond. Much of the labor that goes into Southern Spaces comes from these unpaid critical scholars, photographers, videographers, and writers—our editorial reviewers.

Southern Spaces scroll bar, 2005. Designed by Sarah Toton. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Toton: At the beginning, Southern Spaces operated with stand-alone, static pages using Dreamweaver. Media was stored in wmv and mov files and to implement Google Analytics, we added the Google snippet to the JavaScript on every page. I programmed all the first SWFs (small web format) for the journal's top scroll until 2006 when Franky Abbott took over this task. We formatted all articles using html and made the journal a composite of handcrafted digital objects. Media was always a bit of a challenge, as was walking content through internal review, peer review, and copyright review. We worked with Lisa Macklin, the first director of Emory's scholarly communications office, to create release-permission forms for writers and content creators and to address questions of copyright and intellectual property.

Battle: The look and feel of Southern Spaces changed significantly during my time working on it, particularly when we shifted from Dreamweaver to Drupal 6 in 2010. While planning for that migration, the staff conducted an audience survey that provided insights into changing the site's appearance to become more user-friendly. We created more accessible menu options for navigating the growing content. With the increasing number of multimedia articles and features, we standardized the organization of pieces to enhance accessibility. We shifted from pieces with numerous pages to scroll-down navigation. These changes began with Sarah Toton, before Franky Abbott oversaw the implementation of the redesign by the Southern Spaces staff. It was a giant endeavor that involved extensive discussions, and was carried out with assistance from a Georgia Tech web designer. As someone new to digital humanities, being involved in that process helped me learn a great deal about how to build web-based projects.

2010 Southern Spaces after migration to Drupal, July 28, 2011. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Abbott: When I started working on Southern Spaces in the fall of 2006, it was in transition. During my tenure, I like to think I helped clarify the journal's online identity to its readership and build systems that remain part of the way Southern Spaces operates: setting goals for monthly publication rate, inaugurating topical series, measuring traffic and considering users and use with Google Analytics, tracking workflow with the first project management system, as well as formalizing training for new students in copyediting, research, and review best practices.

Rawson: I began when the journal used an orange color scheme and was hand-coded with Dreamweaver. Our audio and video media was encoded in three different formats for three different media players. Articles had multiple pages.

Melton: Our shift to Drupal allowed streamlined editing and reviewing. In 2015, with the assistance of Sevaa (an Atlanta-based technical group) we migrated to Drupal 7, which updated the look and feel of the site, as well as added much backend functionality.

We also added and reorganized quite a bit of content. When I began, we had no separate category for reviews, which are now important to the journal. We also added an active blog, that allows us to highlight our new publications and makes the journal and its processes more transparent.

Karlsberg: When I joined Southern Spaces in early 2011, it had recently migrated to the Drupal 6 platform. The site's aesthetics felt contemporary and fresh, and new articles read well and were easy to navigate. One major change from the earlier design was a transition from publishing articles on multiple pages to just a single scrolling page. This transition made sense as page load times improved and users became increasingly accustomed to reading online. However, the new design was an awkward fit with a number of older articles and essays which used novel, beautifully conceived navigation schemes, but were often hard to adapt to the new site's design. As we continued to work with Drupal 6, we transitioned from then-archaic downloadable streaming media players in Real, Quicktime, and Windows Media formats to an embedded JW Player that could accommodate audio and video as well as playlists. These changes increased the range of publication types and media Southern Spaces could accommodate.

Southern Spaces homepage tablet display, 2016. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.

As monitors grew and pixels shrank and the web's dominant aesthetic shifted from a three-dimensional emulation of real life to a flatter and more minimal aesthetic, our site began to look dated. Conceived with desktop or laptop computers in mind, it was not as easily read on smartphones and tablets. Analytics showed that our readers increasingly accessed our content on handheld devices, part of a larger trend. These concerns informed a redesign we initiated in 2014 that culminated in the August 2015 soft-launch of the Drupal 7 site. The new site featured larger text and a cleaner aesthetic that minimized visual clutter and emphasized content and essential navigation. It was more responsive on mobile devices and tablets and better enabled larger media. As with our previous redesign, fitting old pieces to the new site was a challenge that sometimes required revisiting layout and navigation.

Doster: In my first few semesters at Southern Spaces, we published in Drupal 6 and were beginning conversations about the redesign. New to both Mac operating systems and coding of all kinds, my first months required a steep learning curve. I had finally mastered our older operating systems when we migrated to Drupal 7.

Software, Platforms, and Technology

What were some of the technical challenges of the journal? What software platform(s) did you use? What systems did you develop and implement? How did these technologies impact Southern Spaces's rendering of scholarship?

Halbert: At first, the notion of focusing software development on the journal part of the projects (namely Southern Spaces) did not occupy our thinking much. All the software development went towards the metadata harvesting brouhaha. What we talked about regarding Southern Spaces were (to me more interesting) questions of innovative scholarship: What should the forms, conventions, and citation standards of an "online" journal be? Remember, this was more than a decade ago. You had to do an inspired job of tap-dancing, wheedling, and convincing most humanities faculty that the two words "online" and "journal" could be used in the same sentence. Technical challenges? Software development? Hell, we just wrote up Southern Spaces's initial content in HTML (Ur-language of the internet). And after having done my share of chasing imagined perfect software solutions, I'm convinced that the technology used for publication is far less important than ensuring scholarly standards.

Having said that, Southern Spaces evolved in technical sophistication tremendously and quickly. We realized that the technical infrastructure of an online journal could not be left in basic HTML. There were a number of iterations of the underlying software as we explored the needs and functions involved in content management. I left Emory well before the move to the Drupal platform; I celebrate and salute the Southern Spaces team for their achievement in implementing this sophisticated and robust new software infrastructure. But I also can't help interjecting a longer-term observation that this moment is always a circle-of-life point. What happens when the day comes for extracting all the content out of Drupal? I can virtually guarantee that a new generation of Southern Spaces editors will be scratching (pounding?) their heads over that challenge.

Skinner: A better question would be what technical challenges did we NOT experience . . . wow. Hand-coding a site was one piece of the puzzle—always complicated and prone to problems. But we also had other challenges—video capture (Martin broke a long-standing rule in the Emory Libraries against purchasing Macs so that we could have our first video editing station), storage, back up, preservation, metadata. Paul O'Grady will remember the weeks we spent working with Emory metadata librarian Laura Akerman. Everything was a blank slate. Everything required decisions.

At launch, we used two platforms—one for the journal itself, and another for the editorial process. Open Journal Software (OJS) was being used by another start-up journal at our sister campus in Oxford at the time. We hoped that OJS would help to streamline and manage all of the editorial functions—submission, responding to authors, circulating a piece for blind peer review, synthesizing the reviews, communicating back to the author the status of a piece, etc. It didn't. It was easier for our editorial board to use email. That meant that tracking was also done by hand, both by Allen as senior editor, and by me as managing editor.

As technologies changed, we struggled to adapt. The challenge—always—was almost non-existent funding and staffing. We were a lean enterprise, and heavily relied on the skill sets of graduate students and the work of widely-scattered scholars. That said, I think one of the reasons we're celebrating our years of publishing incredible scholarship is that we operated on sustainable funding and energy.

Tullos: With Dreamweaver, each digital article became a handmade object. But because the journal was innovative and collaborative, our student editorial staff found the layout and design work interesting and artful even as it was tedious and painstaking. My training in ethnographic fieldwork and videography led Southern Spaces, early on, to publish stand-alone video pieces as well as to embed video and audio as necessary complements to written narrative and interpretation. We received a timely grant from the Lewis Beck Foundation to purchase a digital video camera, microphone kit, and editing suite. This helped us launch our Poets in Place series in mid-2004. As a public-facing publication, we sought to balance the quality of media streaming with the low-tech media players that many people used to access the journal. Here we received help from Jim Kruse who maintained Emory library's streaming service. Also, realizing that most of the scholars we were soliciting material from did not have digital production expertise, we felt it was part of our job to provide assistance in gathering, editing, and displaying media in their articles. And we were "long form" before that became a conventional term. One of our most important multimedia essays, Daniel A. Pollock's "The Battle of Atlanta: History and Remembrance" features the long form and an accompanying web app for cell phones that offers a guided tour of this critical Civil War battle. With the move to Drupal 7 came responsive design for mobile device accessibility and our increased use of social media to entice visitors to Southern Spaces.

Battle: Dreamweaver was time consuming and difficult to learn for a person only moderately tech savvy like myself. For example, after we pasted in text for an article from a Word Document, we then had to go through and add code for breaks, italics, bold lettering, em-dashes, links, anchors, and so on. We also had to find and change all apostrophes or quotation marks in the text, because they always pasted in as the wrong font. All of them. This could actually be a weirdly satisfying task after a long day of classes—like a mindless video game to chase the ugly punctuation marks—but it took time. There was also no spellcheck. Inserting images involved lots of fussing with their size and appearance in Photoshop, and figuring out the places to wrap text around the images. With a small staff, we relied on each other heavily for checking all these "fixes." Together, we tackled the endless technical difficulties that seemed to arise in layout and in converting and uploading videos.

After the move from Dreamweaver to Drupal in 2010, layout became much quicker and there were fewer possibilities for errors. This made a difference in the scholarship and impact of Southern Spaces. We could produce more pieces at shorter intervals. This enhanced the overall activity on the site, and our user audiences grew significantly, which led to more scholarly attention and submissions. On the back end, Drupal was easier to learn than Dreamweaver, so our staff could grow to include graduate students with minimal digital expertise who worked for both long and short periods (in the past, the longer learning curve often meant that a staff member had to work on the site for a while to acquire the technical skills).

Toton: Writing a parser to convert content to Drupal was challenging. The hand-coding was something we'd grown used to and losing that was really hard. My biggest fear wasn't the technical side, but that we'd lose funding or that students wouldn't want to work on the journal. I believed in it and wanted to ensure it moved forward. Southern Spaces could have been run on a WordPress site in terms of technical publishing and delivery requirements, but the quality of the content would have suffered. The majority of time was spent on vetting content, conducting internal reviews, researching primary materials, emailing writers and archives, finding supportive media, researching historical information, gaining copyrights, and formatting the text for an online, born-digital piece.

Abbott: I became managing editor of Southern Spaces amid the 2010 redesign from static html to Drupal. This was challenging for a group of students with no experience of holistic web project design, and limited time and funding. We did the very best that we could though! The migration of individual pieces, which had often been constructed in unique ways, provided a huge quality control challenge and required resilience and creativity. Mary Battle, Katie Rawson, Sarah Melton, Caddie Putnam Rankin, and I put a lot of heart and soul into moving Southern Spaces to a new site. I also helped squeeze the first draft of a peer review dashboard out of our part-time developer on his way out the door so that we could have a more consistent process and better archiving for pieces under review. I also led the transition from the three-format encoding model for media files to a single format with the embedded JW Player.

Rawson: When I began, video encoding was often a struggle. We wanted media to work at low bandwidth for accessibility to the widest group of users, but we also wanted clarity and smooth motion. We had to find media player settings that would work for the greatest number of users. Then there was the variation in original materials. Producers submitted many forms, sizes, playback rates, etc. I cut my technical teeth on making video function well. Around 2011, I worked with Jesse Karlsberg and Alan Pike to improve the system by having one embedded streaming player.

The 2010 redesign had a steep learning curve—it was terrible and ultimately amazing. With Dreamweaver, I had filled legal pads with specifications. The redesign built many of those specifications into Drupal, along with easier systems for laying out images and text and adding footnotes.

Melton: Migrating to Drupal 6, a content management system with databases and added functionality, was a challenge. We spent some time thinking about sustainability processes, consistent file naming conventions, and how to wrangle all our pieces into an organizational schema. Much of the work of running a journal is invisible, particularly on the technical end. We periodically update file types to keep up with web standards for usability and accessibility.

Karlsberg: One continuing technological challenge has been a multimedia player that looks good and is easy for readers and staff to use. In 2012 we adopted JW Player, a customizable streaming audio and video player, but running it meant serving video from an in-house server and purchasing regular updates. We decided to migrate to Vimeo, a cloud hosted service with a fair use policy that aligns with our own, an easy-to-use back end, and a widely trafficked site. While Vimeo can accommodate streaming audio if paired with still images, it's a challenge. Multimedia is a core commitment for the journal, but one for which there's no ideal single tool.

Another challenge is maintaining and updating our Drupal platform. With development of Drupal 8 underway but far from complete, and a strong interest in redesigning Southern Spaces, we decided to remake our site in the Drupal 7 environment. Lacking an easy path, upgrading required a substantial investment of time and resources. As an open source platform with a large and active user base, Drupal offers flexibility, and support. These advantages motivated us, but the challenge of upgrading is nontrivial.

Doster: While we initially migrated all audio content to SoundCloud during the migration to Drupal 7, we quickly encountered incompatibilities between our interpretation of "fair use" and SoundCloud's restrictive copyright policies. As an open-access journal we are committed to pushing the boundaries of scholarly communications. To accommodate our authors' interest in embedding a variety of copyright-protected material according to accepted fair-use standards, we decided to migrate our audio files to an internally-hosted streaming server maintained in Emory's Woodruff Library, once again assisted by Jim Kruse. The in-house WOWZA server grants us control over streaming content and allows us to respond quickly and efficiently to any fair-use contestations.

The Publishing Process

What were some of the editorial challenges you and your colleagues faced during your time at Southern Spaces? How did the role(s) of editorial staff shift during your time at the journal?

Halbert: I quickly realized as we dreamed up Southern Spaces that a key role would be to identify a scholar recognized in Southern Studies to step up and serve as editor in chief. I cannot say how pleased I was that Allen Tullos took this on. I believe that Allen's leadership and persistence is one of the primary factors in the success of the journal, the others being the extraordinary project management, diligence, and creativity of Katherine Skinner and the graduate students recruited into the project. That Southern Spaces maintains a living, breathing network of scholars is the reason that it has survived so far. The lack of scholarly engagement is why all the metadata harvesting portals we built in many of the Mellon-funded projects went by the wayside. While I do think I played a significant role in founding Southern Spaces, it was the involvement and commitment of the scholars serving in editorial capacities that made it blossom.

Skinner: Just getting the basic procedures in place and making decisions about . . . everything! Including: what our publishing schedule would be (rolling, not issue-based since "issues" are a print convention and one of the strengths of the digital medium is its lack of dependence on a one-time issuing of batches of content); how we would update content over time; versioning conventions, naming conventions (URLs that were human readable were important in the early years when we were managing lots of files); what to save and store (master images, video, GIS files, etc.) so that we could create new derivatives in future years as technical standards of quality changed.

Tullos: Southern Spaces would not have come into being or have continued for very long without the work of so many collegial, smart, and engaged graduate students. Each of the managing editors has had skills and talents appropriate and equal to the challenges facing the journal at the time they stepped into the position. Although we never had a significant or secure budget until we became part of the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship in 2013 during Rich Mendola's reorganization of Library and Information Technology Services (LITS), we relied upon Woodruff Library's technical infrastructure and support staff from the beginning.

Toton: When it started, it was pretty much Allen Tullos, Katherine Skinner, Emily Satterwhite, and me helping when I could. Steve Bransford began video editing in January 2004. He filmed, edited, and encoded. Paul O'Grady joined as a fellow for historical pieces in fall 2004. Zeb Baker followed as an editorial associate for twentieth-century history and pop culture and did a retrospective on the Atlanta Olympic Games. Jere Alexander worked as an editorial associate in 2005 focusing on pop culture and literature. Robin Connor and Matt Miller also worked on writing, researching, producing video, and copyediting.

When Franky Abbott came onboard in 2006 I felt like Southern Spaces as a student-operated journal was going to succeed and live on. She operationalized the review and publishing process, identified peoples' strengths, and made the journal hum along.

Battle: One of the most useful skills I learned at Southern Spaces was how to work with and rely on a team for our editorial and layout process. So much academic work involves producing your research in isolation. It can be hard to learn how to reach out for help. We relied on staff to provide editorial criticism, assist with technology questions, and provide insight about overall goals. I learned how to give and receive criticism, and how to benefit from multiple perspectives. Now that I am managing graduate students in my current position at the College of Charleston, I constantly have to remind them to ask each other for help.

Group coordination at Southern Spaces relied on leadership from the managing editor. During most of my time there, Franky Abbott filled this role, and I cannot say enough about her attention to structure, communication, and keeping deadlines. Once we started using the project management software Basecamp, Franky was able to delegate tasks more easily and we could see what other staffers were working on.

When I joined in 2007, many scholars were new to producing digital or even multimedia projects, and seemed unclear about their academic significance compared to traditional print publications. By the time I left, more authors were becoming familiar with digital contexts and taking their possibility and impact seriously. As our audience grew, we received and reviewed more competitive and polished submissions across a range of subjects, gaining invaluable experience about the editorial process.

Abbott: I am proudest of the impact that I had on the culture of the student editorial staff. When I arrived as a research assistant, graduate students came and went from the staff every semester; the editorial process was more of an assembly line where individual students applied a particular skill (html/css, video editing) to relevant pieces as they went to publication. At that time, Dr. Tullos was responsible for all aspects of the in-house editorial process that weren't copyediting. I helped build a student review into the process to give us a chance to develop editing skills while decreasing Dr. Tullos's workload (and getting pieces through the system more quickly). We convinced him to extend more editorial trust by working hard on our reviews and discussing challenges honestly in staff meetings. With the development of topic-focused series, social media accounts, and other responsibilities, I also thought about how to incentivize a multi-year commitment to the Southern Spaces team through increased engagement and skill building. I wanted everyone to get the chance to learn skills that interested them and to then show leadership in that area as they spent more time on staff. This model led to a tight-knit team that worked hard to make the journal better. It was all about creating a culture of investment in the project and encouraging new student staff members to buy in. This didn't happen 100% of the time, but it happened often enough to give Southern Spaces some institutional memory and its students some great experience for a variety of future jobs.

Tires dragged along roads by the Border Patrol to see fresh footprints left by immigrants, Brownsville, Texas, 2010. Photograph from Susan Harbage Page and Inés Valez's photo essay "Residues of Border Control," April 27, 2011. Courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Rawson: One of the challenges was learning to reject submissions that were not going to make it to publication. I can name several pieces that we put a great deal of time into when we probably should have cut our losses. At the same time, I can name pieces that we put a lot of work into that were worth every minute because their content is significant and original. We also had a few challenges that involved student-produced work and figuring out how and if we could accommodate it in a peer review journal. I don't know that these questions were resolved in an ideal way—but I felt like these were important conversations around scholarly production.

During the time I was at Southern Spaces, we supported practicing artists, in particular photographers, in developing photo essays that make significant scholarly contributions—and are compelling. The redesign gave us more time to edit. Also, we began pursuing and including book reviews (thanks Alan Pike!).

Melton: Before we became part of the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, funding for Southern Spaces was a continuing challenge. We had some support from Woodruff Library and from the Laney Graduate School through fellowships.

In general, I've watched the editorial staff become much more comfortable and proactive about the technological directions of the journal. We want staff to leave the journal with a solid set of tech skills that they can use elsewhere. This shift towards overt training sets us apart in many ways—we're teaching staff members how to edit, critique, and build digital scholarship.

Karlsberg: During my time on the journal's staff we added two new regular publication types with different editorial processes than our peer reviewed articles, photo essays, and short videos. Determining how to critically evaluate book reviews and blog posts took experimentation, and, where our decisions broke with common practice, required clear communication with authors. For example, our book reviews undergo rigorous internal review in a genre where author expectations vary widely. Blog posts, which can undergo internal review without the oversight of the senior editor, required a working out of how best to balance prompt publishing with critical evaluation. Our staff also formalized rigorous processes for peer review that were already in practice, helping make clear when editorial staff members take part and how their work contributes to that of the senior editor, editorial board, and external peer reviewers. A parallel challenge was how to train new staff on these processes and expectations, and how to share knowledge about potential publications as they navigated the review process. Better documenting our training process helped us bring new staff members up to speed on our editorial guidelines. Shifting weekly staff meetings from reporting on progress to an opportunity to talk through reviews in progress helped with training and keeping everyone informed about the submissions we were considering.

Doster: Southern Spaces is the product of teamwork and I have benefitted immensely from the hard work and innovation of my predecessors and my colleagues. When I began as managing editor, many of our standard editorial procedures were fully vetted and operational. In 2015, Alan Pike encouraged the journal to adopt Trello, an open-access management tool that we now use to track all phases of solicitation, review, and publication. This tool makes our editorial process easier to follow and manage. In addition to continuing to hone and streamline our internal review—a task that each managing editor and Southern Spaces team takes on—we continue to assess how to best convey digital scholarship conventions to authors more familiar with traditional print publications. On the content front, editorial associate Clint Fluker worked closely with me to revive the Southern Spaces blog. Clint's interdisciplinary work helped keep the blog current and relevant. Editorial associate Kelly Gannon has also championed our more active presence on social media, extending the journal's reach and readership.

Staff Favorites

Describe an article or project that best represents your experience at Southern Spaces.

Halbert: Two early articles are Carole Merritt's essay on the Herndon Home in Atlanta and Will Thomas' essay on television coverage of the civil rights movement. These pieces forced the questions I mentioned earlier: What form should an online journal take? What static elements carry over from print journals and what dynamic elements emerge? The internet enabled the display of high-resolution color photographs and audiovisual clips as evidence in making scholarly claims. It's a medium with many more functional capabilities and flexibility than print.

Skinner: One of the most representative articles I hand coded in the earliest years was Will Thomas's piece on television news and civil rights. This was one of the first articles that demonstrated how a multimedia environment could transform scholarship. It was also the last article that I coded mostly solo—and I used it to help train Sarah Toton in my esoteric xhtml dreamweaver practices.

Toton: I remember Rob Amberg's "Corridor of Change" photo essay being particularly challenging. It encompassed around sixty printed pages and we needed to figure out how to tell his story in an online-friendly format. We worked on that essay off and on for months, stitching it together into a piece that was interesting and nonlinear, yet made logical sense. I also worked on laying out Will Thomas's Eastern Shore piece for months. We researched primary materials, found photos and maps, created galleries, slideshows, graphs, etc. to make it a rich born-digital piece of historical storytelling. After we published, Will sent me a pewter otter statue from an artist on the Eastern Shore.

Battle: Starting in 2009, I served as the editor for the series, "Migration, Mobility, Exchange." This included organizing a call for papers and recruiting and reviewing article proposals. We published seven pieces in this series. This was one of my first leadership experiences at Southern Spaces, and it gave me insights into the editorial process from beginning to end. I was proud of the work we produced.

Abbott: Some of the earliest pieces I worked on in 2007 had a big impact on my own scholarship, my growth as an editor and designer, and my sense of what was possible for Southern Spaces: Kevin Pask's "Deep Ellum Blues" and Terry Easton's "Geographies of Hope and Despair." Also the pieces in the Space, Place, and Appalachia series: Scott Mathews' "John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky" and Earl Dotter's "Coalfield Generations." Matt Miller's "Dirty South." Later, Dot Moye's Hurricane Katrina five-year anniversary photo exhibition. The list goes on and on.

Rawson: Clive Webb's "Counterblast" article exemplifies a Southern Spaces experience to me, because of the multimedia components and its scholarly intervention. It included a mix of public domain images that I found—particularly the released FBI files—and things we had to seek permission for, such as letters from Emory's Rothschild Papers and video from the WSB television collection. It's the kind of article that examines a moment in a particular place and adds to our understanding of the civil rights movement.

Melton: I was a relatively new staff member during the Drupal 6 migration in 2010. The transition was a great opportunity to learn what is required to create and sustain a long-term project. We had six years of article drafts, edited and unedited video, and audio clips and photographs to organize. During this process, I became interested in how we might best support the lifecycle of digital publications. This experience set me on the path to my current career.

Doster: Many of the pieces mentioned above have taken considerable work to translate into the Drupal 7 redesign. As all Southern Spaces content is conceived and laid out in a specific platform, migrations often require piece-by-piece updates to retain or improve upon previous design and layout. The 2014 Battle of Atlanta publication, for example, required several modifications in its original layout to build a multi-media essay with accompanying app. While the piece is still engaging, the layout isn't as tight in Drupal 7. Updating older pieces while maintaining an active publishing schedule remains a perennial challenge.

Graduate Student Training

How do you understand Southern Spaces's scholarly and pedagogical missions?

Halbert: Southern Spaces provides tremendous research content for interdisciplinary scholarship. It also represents learning and training opportunities for the graduate students who work on it. Many of these students built on their experiences when they progressed to their own careers.

Skinner: Southern Spaces had huge ambitions from 2003, when it was just an idea, and I think those have fed into its mission and its accomplishments. It is no accident that I was a grad student and was given a tremendous amount of access to and collaboration with seasoned and highly respected scholars in the field. From its inception, senior editor Allen Tullos and key library supporter Martin Halbert, engaged students in the work of the publication. Part of the journal's purpose has always been to support the next generation of scholars, giving them exposure to and a voice in scholarly communications. Many of us who have worked on Southern Spaces credit it with leading us into our careers and giving us the skill sets, connections, and street cred we needed to succeed.

A key facet of the Southern Spaces mission is its engagement. That training is similar to what some university presses once did. It benefits the students and enriches the publication. Southern Spaces explores and enables multimedia scholarship in ways that few other publications have done—using the power of the medium, including its huge audience base (much larger than the academy's) in the process. It's a demonstration of public scholarship that crosses boundaries and engages people in different spheres.

Toton: At a selfish level, Southern Spaces is something I can share with my mother. She's often overwhelmed by academic or scholarly writing. I love Southern Spaces because it's open-access so I can send her links for great articles. She reads them, understands and appreciates their points, and we can talk about them. They're accessible. She's excited when new pieces appear.

Battle: When I first started at Southern Spaces in 2007, digital humanities felt like an emerging field. DH has a much longer history, but most academics I knew at that time were not particularly involved. The staff sometimes experienced skepticism from other students and from faculty about dedicating so much time and energy to the journal in the midst of a PhD program. Awareness of the value of this student experience started to grow, but I did not realize the impact digital humanities would have on how I conceptualized scholarship and my future career until I finished working on the journal. The pedagogical importance of digital humanities has since become more recognized at Emory, which I see as a great thing. I learned not just how to build a project using different technology platforms, but also how to conceptualize project structure, workflow, partner collaboration, and layout possibilities. These conceptualization skills have proven crucial in my current work with the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative at the College of Charleston.

Abbott: Southern Spaces offers its graduate student staff the opportunity to have real responsibility in a deeply collaborative environment. This is so rare. Most graduate student jobs are isolated or short-term. They don't offer the kinds of editorial, digital, and team-oriented skill building that a variety of employers look for. Southern Spaces gives students the ability to show off individual work through edited pieces or curated series as well as their contributions to the growth of a whole project and team. It's also rare for a faculty member (in this instance Prof. Tullos) to devote so much time to a student-staffed project, to be that big an advocate for the students, and to use so much of his own time, energy, and intellectual bandwidth to see it grow in positive directions.

For readers, I think Southern Spaces is a smart, well-articulated experiment that they can watch grow and change. The journal publishes academic content alongside artistic and journalistic forms. And Southern Spaces does this in the context of an organized, digital space that capitalizes on the best aspects of that medium: redesigns, updates to functionality, attention to usability, interaction with users, timeliness, rolling submissions. Plus, it's one of the oldest living open access journal surrounded by a graveyard of other open access journals, which says something in and of itself.

Rawson: Two parts of Southern Spaces scholarly mission are central to how I understand it and why I love it: Southern Spaces publishes critical scholarship that is accessible—in medium and style—and Southern Spaces demonstrates that scholarship is more than interpretative text on a page, not simply enriched but made more significant by including primary sources, maps, photography, audio, and film. The journal offers a wide spectrum of what research is, as well as insight into the construction of culture and geographies, the intersection of lived experiences of people and politics, and the ways that places and spaces shape individuals and societies.

Southern Spaces provides three important forms of training. First, intensive scholarly training: editorial staff learn to assess arguments and evidence within the context of multiple fields of inquiry including American Studies, geography, and history, ultimately constructing and revising scholarly publications. Second, training with technology: the details change over time, but Southern Spaces is always on the edge of new media and methods in research and publishing, whether video, digital tools, copyright, GIS, or design. The training is the best, because it is driven by needs and goals. We learn and we teach because that is what keeps the journal going.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, Southern Spaces provides professional training that opens doors and builds careers. I learned how to run a meeting. I learned how to train and manage others as well as how to work collaboratively with peers, with people who are experts and leaders in their fields, and with people who are just venturing into academia—and in situations where everyone did not see eye-to-eye and where solutions were hard won. I learned how to write emails that were direct, tactful, and productive; to write a form email, organize a major transition, develop a workflow, cold call archives and artists, and how to find resources in a complex institution.

Melton: We take time trying to define who our publics are, and I'm not sure we'll ever get a final answer. I've watched our readership grow in ways that I could not have expected, from K-12 students to university librarians to history buffs, and everyone in between. This diversity is part of what I love about the journal (I once found my own article cited on a blog about football). It's clear from readership analytics that our policy of making work open access and minimizing the use of academic jargon has garnered a wide audience.

Karlsberg: Southern Spaces embraces scholarly rigor and an interdisciplinary orientation incorporating history, English, music, anthropology, sociology, and geography as well as interdisciplines such as critical regional studies, critical race theory, sexuality studies, women's and gender studies, and of course space and place theory. The journal also adopts a critical posture that it took me a while to absorb that likewise challenges conventional scholarly and public understandings of the South. Southern Spaces critiques the idea of a monolithic South, eschewing romanticization and stereotypes. The journal advances a vocabulary that complements this critique, urging authors to scrutinize "region"; to reserve "region" rather than "subregion" for geographies such as the Delta or the Black Belt; and to refrain from capitalizing the terms "southern" or "southerner" except in their historically nationalist frame of reference.

Southern Spaces equips the graduate student editorial staff with technical, editorial, and conceptual skills that will aid in the job market and expand career possibilities. Staff members also acquire technical skills—ranging from video, audio, and image editing to familiarity with markup language and web design, to working with interactive mapping tools such as CartoDB—which prepare them for positions involving the digital humanities at university departments, libraries and beyond academia. Staff participation in a digital scholarship graduate training program initiated in the fall of 2015 by ECDS staff member and former Southern Spaces review editor Alan G. Pike, extends and formalizes this process.

Space/Place and the US South: A Critical Approach

What did you learn about critical regional studies, new approaches to the US South, and spatial imaginaries?

Halbert: These are of course some of the most intriguing intellectual foundations of Southern Spaces, and the perspectives that excited us most in its creation. The journal has very effectively challenged and ramified conceptions of the South.

Skinner: I will never, ever approach "the South" or, indeed, any other broad space, as though it can be defined in one dimension. I learned to appreciate pluralities. I also learned that those pluralities can be found in a variety of subject matter—from quilts to poems, and from tree farms to TV broadcasts.

Toton: I moved to a PhD program at Emory from Iowa. I had no understanding of where I would be living beyond that it was in "The South." The idea was nebulous, foreign, antiquated and downright scary. Southern Spaces helped me understand that the South was a collection of regions, and of neighborhoods. This insight influenced not only how I started to understand Atlanta, but the surrounding areas. It taught me the importance of the intersection between geography and cultural studies by repeatedly offering examples of how places impact people and vice versa.

Battle: Being involved in the review and editorial process at Southern Spaces significantly expanded my ability to critically engage scholarship about the US South. In my dissertation research and as a public historian, dismantling traditionally exclusive representations of Charleston's historic tourism landscape to include African American history, as well as the history of slavery and its legacies, is central to my work. My experiences with Southern Spaces helped provide me with the skills to take on this challenge.

Abbott: Discussions of space and place, especially in southern studies, can be abstract, easy, assumptive, and essentialist, or they can be particular and meaningful ways to think about identity, context, and social constructions. Working on Southern Spaces teaches you to know the difference between these when you see it. And how to make use of a map.

Rawson: Southern Spaces conventions are so engrained in me now that I have a hard time seeing them. Southern Spaces asks for certain approaches to language, which is one of the first things I learned as an editorial associate. At the time, I remember feeling exasperated with some of these distinctions; however, I have come to understand how powerful it is to attend to the specific geography of places, the pieces of history and environment that shape a piece of soil, that make imagined Yoknapatawpha, lived Lafayette County, the state of Mississippi, and an imagined literary South each have their own meaning and influence. When we move between these places and scales of place discursively, we must be intentional and attentive.

I also am a real believer in Southern Spaces's mission to expand what people publish—whose stories get told, what the subject matter is, what counts and how places are connected. I am glad that we have chosen to publish difficult stories, work that accounts for what is violent and unjust, as well as work that examines how people respond creatively and productively to facilitate change.

Melton: Coming from an American Studies background, I had already thought a lot about the ways we define the South and the necessity of avoiding monolithic descriptions. Working at the journal has helped broaden my understanding of how to understand the US South and the global South in relation to each other. Mary Frederickson's article on the connection between labor practices in the Carolinas and Uzbekistan remains one of my favorite pieces for precisely this reason.

My own dissertation research examines connections between the struggles for civil and human rights in the US South and South Africa. Southern Spaces has helped me to analyze how people understand the interplay between global and local histories.

Karlsberg: My work at Southern Spaces influenced and was concurrent with my growing interest in applying a critical regional frame to my scholarly work on Sacred Harp singing. I was initially drawn to southern studies because the culture accompanying this musical genre is most widespread in several southern states, but until I began reviewing, discussing, and editing Southern Spaces's submissions, I had little sense of the recent critical turn away from southern exceptionalism and toward analysis of the constructedness of the concept of the "South"—and the acknowledgment of the many intersecting people and southern regions.

Doster: Coming from Appalachian Studies, I was eager to find a cohort of critical regionalists at Emory. At Southern Spaces, I worked among dialogue partners and colleagues invested in critical approaches to the study of the South's many sections. At times, I have questioned the journal's framing—I'm still working out my own relationship to the term "community"—but I have a deep appreciation for Allen Tullos's vision and commitment to fresh narratives and new approaches to southern spaces.

Professional Development

How did your work with the journal influence your professional career goals and employment trajectory?

Halbert: The various projects that collectively comprised what I called the MetaScholar Initiative, and in particular the role I played in the creation of Southern Spaces, are some of the career achievements of which I am most proud. The perspective and experience that I gained during the thirteen years I was at Emory have informed my work subsequently as a library dean in thinking about the broader needs of the university.

Skinner: There isn't a day that goes by that I'm not referencing the experiences and using the skills that I first honed working on Southern Spaces.

Toton: My background in digital publishing and migrating journals to content management systems was the reason I got a position at Turner as a technical product manager. After Southern Spaces, I helped design the content management system used to publish some of Turner's news and sports websites.

Battle: Southern Spaces ended up playing a very influential role in my career. After I moved to Charleston, I found part-time work at the Lowcountry Digital Library (LCDL) housed at the College of Charleston. When my boss at the time, Dr. John White, asked me to update some online exhibitions connected to LCDL, I was able to conceptualize new ways to develop the exhibitions altogether, and to organize a cohesive digital public history platform rather than a series of stand-alone projects. We successfully received major grant support in 2011 and 2013 to launch the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative (LDHI) in 2014. In 2013, I finished my Emory PhD and became the public historian at the College of Charleston's Avery Research Center. The workflow for LDHI online exhibitions relies heavily on the collaborative student work model and editorial process I learned through Southern Spaces.

Abbott: Southern Spaces was the turning point in my own career. I joined because I was interested in southern studies. I left a digital project manager. For many of the core team, the idea was that if we made Southern Spaces as good as possible, we would be rewarded through our affiliation with it on the job market. It was a great and rare kind of experience to have as graduate students and I think it's clear this gamble paid off for us. I wouldn't have had any of the jobs I've had since I graduated without Southern Spaces. It was Southern Spaces that showed me that I didn't want to be a traditional academic and that I would be skilled at a different path. Since graduating from Emory, I've run a digital humanities center at the University of Alabama and I'm currently working as a curation and education strategist for the Digital Public Library of America.

Rawson: My career is what it is because of Southern Spaces. After I completed my American Studies PhD at Emory, I became the coordinator for digital research at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Southern Spaces was one of the key factors in my investment in digital scholarship. It prepared me for much of the work that I do and gave me connections that are important for my career. My relationship to Kat Skinner is one example of this. Of course, the group I went through with—Franky Abbott, Mary Battle, Sarah Melton (along with Miriam Posner who sat at the cube over from us)—is the core of my professional network. It is a network that is noticeable at conferences like ASA and DLF. Working at Southern Spaces also helped me understand the importance of supporting people on the alt-ac track. I realized that I like other kinds of work in addition to teaching and research: I like working in teams, at set hours, on projects with clear timelines. Further, I can excel at these things and create and facilitate work that is meaningful. After two-and-a-half years at Penn, I returned to Emory in 2016 in a position as a humanities librarian that emphasizes my digital skills.

Melton: My time at the journal shaped my professional employment trajectory in ways I could not have anticipated. I became interested in open access publishing more generally and began working towards better situating Southern Spaces in the publishing landscape. After the formation of Emory's digital center, I was hired as digital projects coordinator and worked with several of our open access publications. I've become more involved with open educational resources and open data efforts. Southern Spaces has connected me to an international network of people interested in improving scholarly communications. Along the way, I've also learned invaluable skills about managing people and projects that prepared me for my current job as head digital scholarship librarian at Boston College.

Redux homepage, September 2016. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Karlsberg: My work at Southern Spaces has taught me how much I enjoy collaboration, editing, and facilitating the publication of excellent and important writing. Thinking critically about the publishing platform of Southern Spaces introduced me to exciting conversations about digital humanities and the future of scholarly publishing. This contributed to my interest in my next positions: a postdoctoral fellowship centered around the editing of a series of digital critical editions of turn-of-the-twentieth-century US tune- and hymnbooks and a fulltime job as senior digital scholarship strategist in ECDS. In this new role, I manage an open access, multimodal journal and blog featuring interdisciplinary scholarship on Atlanta called Atlanta Studies, continue to work on the proof-of-concept series of publications for a platform for digital critical editions called Readux, and contribute to numerous collaborative research and publishing projects in helping to streamline our center's project process. I remain interested in positions that combine teaching and research but now also hope to make editing and involvement in the future of scholarly publishing a part of the mix.

Southern Spaces: What's Next?

How do you see Southern Spaces evolving in the next ten years? What goals do you have for the journal as it moves forward?

Halbert: There are an enormous number of future avenues for Southern Spaces. Clearly, the basic pattern and best practices of digital scholarship of the journal have now been thoroughly laid down and explored, and should be continued as they constitute some of the best and most accessible digital scholarship available anywhere today. The question comes down to what new directions (if any) Southern Spaces should consider. There are at least two speculative issues. First, is the potential relationship of Southern Spaces with the other big website that I helped create and had to leave behind when I left Emory, namely the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database (slavevoyages.org). The second is the potential connection between Emory and the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), where former Southern Spaces managing editor Franky Abbott now works.

The significance of Southern Spaces should be evident to everyone that encounters it, as one of the most successful experiments in digital scholarship to have been created to date and as a model for collaboration between researchers and librarians.

Skinner: I hope to see Southern Spaces continue to widen the net and attract many different people to scholarly writing by addressing questions that matter throughout society. I hope it continues to bend what "scholarly writing" is—emphasizing quality, not pedigree, and engaging forms beyond the article, like the reviews, poetry, video, etc. that it already publishes. I hope the journal continues to be propelled by the fabulous ideas and energy of the students who are trained by and contributing to its form over time.

Toton: I think the content has become more diverse and prolific as the journal has enlarged its staff. I love the reviews and hope to see more student-written pieces. I think that the "Southern Spaces Blog" ought to be folded into the general content.

Battle: I am very excited to see where and how Southern Spaces grows. I'm sure we will continue to have plenty to learn from what the journal produces. From my own experience directing the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, we hope to expand our work on multi-institutional projects as well as projects with individual authors. For example, our current works-in-progress include projects with smaller cultural heritage institutions, translating physical exhibitions to an online context (particularly museums that do not have the resources to host their own online exhibitions). We are also working with library and museum institutions to produce exhibitions that highlight archival collections. With the resources at Emory, it could be interesting to see what similar institutional collaborations could produce through Southern Spaces, particularly for public-facing projects as well as scholarly works.

Abbott: Southern Spaces will have to keep pace with ever-evolving web design. Each generation of Southern Spaces staff thinks the site is a dinosaur and can't wait to make changes. That energy will keep it healthy. Now that the journal has a more stable home in ECDS, I think new collaborations are possible. I want Southern Spaces to never let itself fall into traditional academic modes of discourse—but to continue to push for experiments with video, photography, perhaps the exhibition as a medium. I'd love to see Southern Spaces work more closely with materials from the many great archives at colleges and universities, museums, historical societies, research centers, in pieces that place digital content curation at the narrative center. I also hope Southern Spaces continues to make plans to sustain itself for the future—by consistently engaging and growing the editorial board, seeking grant funding for special projects, providing staff support for graduate students, staying on the bleeding edge of conversation in both digital humanities and critical regional studies.

Rawson: I hope the journal continues to gain readers in the academy and beyond. I expect it to continue to publish important work and new forms of scholarship and to engage with literary production and public scholarship. I hope it continues to expand its role as a space for critical conversation around politics and social justice. On the technology side, I think Southern Spaces has the potential to be a great commuter/wait-time read and hope that the mobile presentation of the journal keeps up with devices and users' reading practices.

Melton: I'm proud that Southern Spaces is an incubator for new directions in scholarly publishing. With the launch of our redesigned site we're also experimenting with new ways to measure the journal's reach. I want to see more of this spirit of experimentation. I also hope Southern Spaces will continue to serve as a model for other publications, both technically and in the context of student training as it seeks to manage sustainability and currency.

Karlsberg: Technologies and design conventions of web-based publishing shift rapidly. Committing to web-only publishing creates opportunities for our authors, yet obligates us to periodically remake our site to preserve and enhance access to what we've published. This also provides us with an opportunity to embrace new tools and to share what we develop. Over the four year period I served as a member of the staff we redesigned the site twice, switched audio and video formats as many times, and introduced new tools for slideshows and interactive mapping. I expect Southern Spaces will continue to revisit these choices as new technologies emerge. As Southern Spaces moves forward I anticipate it will continue to pioneer innovations in the form of scholarly journal publishing that others can learn from and adopt, and that this will enable us to continue to keep our own presentations of scholarship current.

Doster: I'd like to see the journal move into a stronger advocacy role among its peer publications and in national networks, and to continue to model the training of doctoral students in academic digital publishing. I also advocate for long-term planning that regularly assesses the journal's management structure, the sustainability of its staffing model, and its replicability.

Tullos: In 2003, as we began planning what became Southern Spaces, we imagined that other scholarly journals would soon participate in this new model for digital publishing (beyond the pdf) by creating multi-media content formats, expanding open access, and providing grad student training. For many reasons that include slow-to-change academic publishing models, scholarly-society inertias, antiquated tenure and promotion practices, and limited institutional resources—especially following the Great Recession—there are still few digital publications such as ours. In the intervening years we've learned a good deal about the field of scholarly digital publishing, acquiring insights about what works and what to avoid. In this spirit, we welcome inquiries from interested institutions and editors. As our primary emphasis remains with critical content, we hope to continue our commitment to regional studies through original scholarship about southern regions, and exemplary examples from regions far and wide.

Cover Image Attribution:

All photographs by Tom Rankin. Collage by Eric Solomon, 2017.Recommended Resources

Text

Boismenu, Gérard and Guylaine Beaudry. Scholarly Journals in the New Digital World. Translated by Maureen Ranson. Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press, 2004.

Gold, Matthew K., ed. Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu.

Gardiner, Eileen and Ronald G. Musto. The Digital Humanities: A Primer for Students and Scholars. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Web

Alabama Digital Humanities Center. “Projects.” https://www.lib.ua.edu/using-the-library/digital-humanities-center/adhc-projects/.

Ayers, Edward L. “Does Digital Scholarship Have a Future?” Educause Review. August 5, 2013.

http://er.educause.edu/articles/2013/8/does-digital-scholarship-have-a-future.

Creative Commons. https://creativecommons.org/.

DHCommons. http://dhcommons.org/.

Digitalhumanities. “The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0.” May 29, 2009. http://manifesto.humanities.ucla.edu/2009/05/29/the-digital-humanities-manifesto-20/.

Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/.

Dinsman, Melissa. “The Digital in the Humanities: A Special Interview Series.” Los Angeles Review of Books. 2016. https://lareviewofbooks.org/feature/the-digital-in-the-humanities/.

Emory Center for Digital Scholarship. http://digitalscholarship.emory.edu/.

Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. http://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/.

UCLA Digital Humanities. "Projects." http://www.cdh.ucla.edu/projects/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Martin Halbert, ed., Workshop on Applications of Metadata Harvesting in Scholarly Portals, MetaScholar Initiative, October 24, 2003, Emory University General Libraries. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277283794_Workshop_on_Applications_of_Metadata_Harvesting_in_Scholarly_Portals_Findings_from_the_MetaScholar. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Donald J. Waters, "The Metadata Harvesting Initiative of the Mellon Foundation," ARL: A Bimonthly Report, no. 217 (August 2001): 10–11. arl.org/storage/documents/publications/arl-br-217.pdf. |

| 3. | Charles Reagan Wilson, "A Scholar's Perspective on AmericanSouth.Org," in Halbert, ed., Workshop on Applications of Metadata Harvesting in Scholarly Portals. |

| 4. | See "About," at http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/. |