Overview

The Shenandoah Valley

Edward Beyer, Digital Restoration of "Harper's Ferry from Jefferson Rock" from Album of Virginia: Illustrations of the Old Dominion, 1858.

The Shenandoah Valley's history marks it as a distinct region of the American South with a geography that has encouraged in-migration, land and industrial development, and trade.

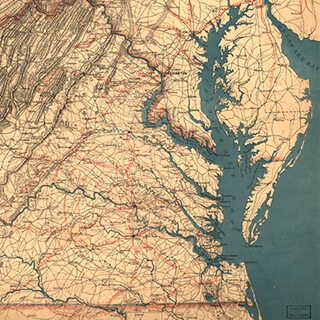

The Shenandoah Valley has a habit of confounding and surprising visitors. In local parlance to go "up the Valley" is to go south and to go "down the Valley" is to go north. In both cases the direction is relative to the great rivers that bisect the valley: the North and South forks of the Shenandoah River. In fact, there are two rivers and two valleys for much of the Valley, as the Massanutten ridge separates the forks of the Shenandoah for over 40 miles on their course northward. They join in northwestern Virginia near Front Royal and then the Shenandoah continues its flow northward until it joins the Potomac at Harpers Ferry.

The Shenandoah Valley encompasses the part of the Great Valley, or the Great Valley of Virginia, that is the drainage for the Shenandoah River. As a geographic entity, however, the Great Valley extends beyond Virginia into Maryland and Pennsylvania, bordered continuously by the Alleghany and Cumberland Mountains to the west and the Blue Ridge and South Mountains on the east. The valley floor contains one of the richest agricultural regions in the eastern United States.Any visitor quickly loses his or her sense of direction in this setting, just as the Northern troops facing Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Confederate forces did in the spring of 1862. After a few years experience in the Valley, however, Northern troops under General Philip Sheridan in 1864 thoroughly understood the region's complex geography and its social and economic landscape; so much so, that they systematically conquered it.

The breathtaking beauty of the Shenandoah Valley is not only evoked in its Indian name which means "Daughter of the Stars" but also in the wide ranging literature about its rivers, streams, mountains, caves, and springs. Thomas Jefferson, in his Notes on the State of Virginia, described Harpers Ferry, for example, as one of the most "stupendous scenes in nature." From the high land above the rivers, he wrote, "On your right comes up the Shenandoah, having ranged along the foot of the mountain an hundred miles to seek a vent. On your left approaches the Potomac, in quest of a passage also. In the moment of their junction, they rush together against the mountain, rend it asunder, and pass off to the sea."

The Valley's natural resources, beauty, rich soil, abundant water, and mild climate have contributed to its position as one of the most dynamic regions in Virginia, the South, and Eastern America. From the earliest human presence in the region over 10,000 years ago, the Valley was a central corridor for travel, migration, hunting, and planting. The Valley was the homeland for no single tribe, and Eastern Woodland Indians used it to occupy the edges of their tribal territories and as an avenue for travel and warfare.

The Monacan occupied the Shenandoah and the upper James and Piedmont regions, but they were under constant challenge from large tribes on all sides. To the north the powerful and dominant Susquehanna moved into the Valley at several points to travel south and hunt. To the east the Powhatan Confederacy loosely allied tribes in the upper coast plain. Scientists have characterized the Valley as a vast grass prairie in the early seventeenth century. Native American tribes burned large sections of it annually and settled in villages along its many streams and rivers.

In the eighteenth century the Valley was the backcountry frontier of the colonies. Settlers from Pennsylvania, many of them Germans and Scotch-Irish, some of them Quakers, nonconformists and dissenters, crossed into the lower Valley, and eastern Virginians moved from the Piedmont west through the gaps along the Blue Ridge. Colonial Virginia governors and officials were glad to encourage settlement in the Valley as a buffer against French and Indian claims in the mountains west and north.

In part because of its heavy settlement from Pennsylvania, the Valley has been called "a world between," or the "third South," part of middle America, where according to some historians there was less commitment to the Southern cause in the Civil War and even less to the institution of slavery. Historians point to the large influx of Pennsylvania religious dissenters and non-conformists who would not countenance slavery and to the distinctive agricultural practice of mixed crops they brought with them.

The idea of the Shenandoah as exceptional to the South is understandable but problematic. In the eighteenth century tidewater and Piedmont planters speculated in land in the Valley and planned to move their operations to its rich soil. They brought with them hundreds of enslaved people, encouraged land development, and expected slavery to flourish in the area. By the eve of the Civil War Shenandoah Valley residents included around 25 percent of the total population enslaved. There was significant sub-regional variation in the spread of slavery across the Valley; in Clarke County, for example, nearly half of the population was enslaved, in Augusta one quarter, and Rockingham ten percent.

Recent scholarship, however, has stressed the pervasiveness of slavery in the Shenandoah, its adaptability to mixed crop and wheat production, and its connection to the development of the railroad. In Augusta County, for example, slavery in 1860 was widespread, affecting every aspect of social and economic life. Slavery, it turns out, was most pronounced where economic development forces were the strongest. Railroads, industrial enterprises, cash crop agriculture, businesses and institutions fed and were fed by slavery.

Just as significant for the Valley's identity and character, slaveholders heavily influenced its politics in the nineteenth century, and the social logic of the slaveholders extended deeply into the region. Although most of the Valley counties voted for John Bell in 1860 and for unionist candidates to the constitutional convention to consider secession in 1860-61, Valley white citizens interpreted these events within the context of their social and economic system dominated by slavery. In the final choice in April 1861, most of the Valley counties gave themselves over fully to the Confederate cause, with conviction and determination.

In the Civil War the Valley became a strategic theater of operations. In 1862 and 1864 major Union campaigns in the Valley aimed to capture or disable what was widely called "the breadbasket of the Confederacy." In the fall of 1864 General US Grant directed General Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah to "eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they [Early's army] go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their provender with them." Sheridan's troops burned large swaths through the Valley, drove off livestock, and scattered the Confederate forces. In the campaign one main objective was the Virginia Central Railroad which linked Staunton in the Upper Valley with eastern Virginia through Rockfish Gap. The line was a vital connector to Robert E. Lee's army defending Richmond; it carried food to Lee's army and in years past carried Confederate forces into the Valley on missions to use the Valley's broad plain to move quickly north to cross the Potomac, threaten the capital, and take the battle to Northern ground.

Sheridan's raid went into local history as "the burning." Far from destroying the entire Valley and subjugating its population, Sheridan's forces inflicted limited and targeted damage. Sheridan claimed that his cavalry units captured or destroyed so much civilian property that the Valley "will have little in it for man or beast." Sheridan's final report on the campaign stated that his troops destroyed or captured 3,772 horses, 10,918 cattle, 12,000 sheep, 15,000 hogs, 20,397 tons of hay, 435,802 bushels of wheat, 77,176 bushels of corn, 71 flour mills, and 1,200 barns. Rockingham County did a thorough survey of the damage, however, and apparently lost 450 of the 1,200 barns, 31 of 71 flour mills, and 6,000 of 20,000 tons of hay destroyed in the Valley. In Rockingham County where Sheridan's cavalry visited widespread destruction, the county's estimate of total losses represented less than a quarter of the county's production levels in 1860. Still, the burning was reported widely in diaries and letters and invariably described as lighting up the night skies, visible for miles from the mountain ridges and outcrops.

If the Valley had always been an avenue of transportation, migration, and development, after the Civil War it continued in this role. It was the corridor for regional development of new industries, mines, hotels, and railroads. Its leading citizens played active roles in the push for economic development of mineral wealth. Jedediah Hotchkiss surveyed the region, met with investors, started land development companies, and published and spoke about the Shenandoah Valley. He served in the Confederate Army under Jackson as a cartographer and became known as the "mapmaker of the Confederacy." Hotchkiss and his associate, John D. Imboden, helped promote railroad and coal mining throughout southwestern Virginia, Appalachia, and the Valley in the 1870s and 1880s.

The beauty of the region attracted investors to build hotels and resorts, especially near the hot springs, natural wonders, and caverns in the mountains. A flourishing tourism business developed in the nineteenth century around these resorts. By the 1920s some Virginia leaders wanted to create a national park in the region to attract tourism. These boosters spoke of harvesting the "scenery crop" and expected a national park in the Shenandoah to bring many thousands of visitors a year from the eastern cities and many millions of dollars into the region. Park boosters engineered state takings (under eminent domain) of the land from mountain and Valley residents and in 1934 turned the land over to the federal government to create the Shenandoah National Park. In the process hundreds of families were forcibly removed from their homes.

The removals stirred animosity and resentment among longtime residents in the region toward the state and federal officials, as well as the local brokers, who created the park. Park promoters and historians for years tried to justify the taking by fabricating cultural, economic, social, and ethnic differences between the mountain and Valley residents. Mountaineers were stereotyped as subsistence farmers, clannish (Scotch-Irish), inbred, reclusive, and backward, a distinct group from the independent, frugal, German Valley settlers and the rest of Virginia. Recent research, however, has shown clearly that these stereotypes not only were badly mistaken but also purposefully circulated. Mountain residents grew the same crops, marketed them in the same commercial systems, and entered new local industries in the same ways as their neighbors in the Valley throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The creation of the national park was part of a long pattern of boosterism and economic development in the Valley, but it did herald a change in scope and scale. Larger and larger institutions opened business in the Valley throughout the twentieth century. DuPont, Coors, Tyson, Wampler, and Merck each have massive plants there, making it one of the most heavily industrialized regions in Virginia. The American Farmland Trust recently designated the Valley as one of the most threatened regions in the nation, as housing development, agribusiness, and industry spread across the landscape. The Shenandoah National Park, created for the purpose of boosting the region and in the process squelching some of the indigenous development underway there, stands ironically now as a buffer against encroachment. The Valley's natural beauty may be as endangered as its historic landmarks in large part because the region's natural advantages have differed so little over four hundred years--a fertile land for agriculture, a transportation network with easy access to the east and west, an abundance of water, and an array of natural wonders.

Cover Image Attribution:

Mount Marshall, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, October 21, 2014. Photography by Flickr user David McSpadden. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.Recommended Resources

Text

Gallagher, Gary ed. The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Hantman, Jeffrey. "Monacan History and Archaeology of the Virginia Interior," in Societies in Eclipse: Archaeology of the Eastern Woodland, AD 1400-1700. D.S. Brose and R. C. Mainfort, eds. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

Koons, Kenneth E. and Warren R. Hofstra, eds. After the Backcountry: Rural Life in the Great Valley of Virginia, 1800-1900. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000.

Lambert, Darwin. The Undying Past of Shenandoah National Park. Boulder: Roberts Rinehart, Inc., in cooperation with the Shenandoah Natural History Association, 1989.

Perdue, Charles and Nancy J. Martin-Perdue. "'To Build a Wall Around These Mountains:' The Displaced People of Shenandoah." Magazine of Albemarle County History (1991) 49:48-71.

Web

Ayers, Edward L., William G. Thomas, III, and Anne S. Rubin, The Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War. http://valley.vcdh.virginia.edu

Horning, Audrey J. "When Past is Present: Archaeology of the Displaced in Shenandoah National Park." National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/shen/historyculture/displaced.htm