Overview

In October 2022, during oral arguments in a US Supreme Court case concerning reapportionment, Justice Samuel Alito suggested from the bench that racial bloc voting in Alabama is a partisan, ideological difference, unrelated to race. Steve Suitts reviews this voting rights case and briefly explains how Alito ignores Alabama's long history of race-based voter suppression and why, if adopted in future cases, Alito's ahistorical assertion could devastate Black voters' chances to win voting rights challenges across the nation.

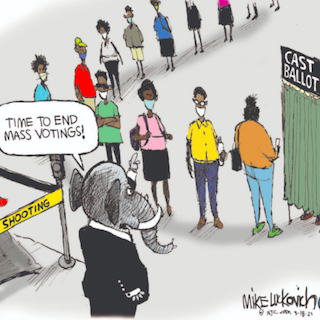

The US Supreme Court has chosen to hear several cases this term that could overturn many of the laws and practices the nation has come to accept as instrumental for advancing a fair, democratic society—affirmative action in higher education, LGBTQ rights, Native American sovereignty, the electoral college's essential integrity, and the voting rights of Black citizens. In some of these pivotal cases, it isn't entirely clear if the Court's new conservative majority will stay together for at least five votes, but in the voting rights case, it seems only a question of how—not if—the current US Supreme Court will reduce federal protections for Black and other minority voters.

A case argued in October 2022 concerning Congressional reapportionment in Alabama reveals that the Court's conservative majority is likely poised to follow the lead of Associate Justice Samuel Alito, who in July 2021 wrote the Court's majority opinion reinterpreting the Voting Rights Act's Section 2 to make it more difficult to win a case challenging laws that restrict voting procedures.1 Steve Suitts, "Undoing the Voting Rights Act," Southern Spaces, July 12, 2021, https://southernspaces.org/2021/undoing-voting-rights-act/.

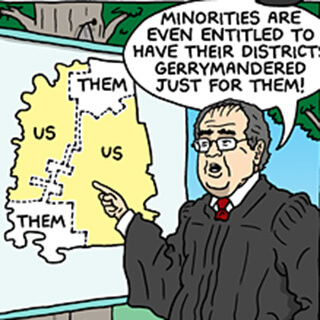

By further crippling the Act's Section 2, instead of voiding it completely, as the Court did nine years ago to the Act's Section 5 in an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts involving Shelby County, Alabama, the current Court will reach the same practical result: overturning the ruling of a three-judge court (composed of two Trump-appointed and one Clinton appointed federal judges) that would permit Alabama's Black voters—one-fourth of the state's population—an opportunity to help elect a candidate of their choice in two (not just one) of the state's seven Congressional districts.2Amy Howe, "In 5–4 vote, Justices Reinstate Alabama Voting Map Despite Lower Court's Ruling that It Dilutes Black Votes," Scotusblog, Feb. 7, 2022, https://www.scotusblog.com/2022/02/in-5-4-vote-justices-reinstate-alabama-voting-map-despite-lower-courts-ruling-that-it-dilutes-black-votes/; Merrill v. Milligan, 142 S. Ct. 879 (2022); Shelby County, Ala. v. Holder, 570 US 529 (2013). Steve Suitts, "States Rights Resurgent: The Attack on the Voting Rights Act," Southern Spaces, Aug. 29, 2013, https://southernspaces.org/2013/states-rights-resurgent-attack-voting-rights-act/.

The case, Merrill v. Milligan, will adversely shape voting rights in Alabama and across the nation, but the worst is yet to come if Justice Alito's remarks from the bench on October 4 foretell the Court's future approach. In an exchange with the US Solicitor General, who sided with Alabama's Black plaintiffs, Alito proffered a couple of far-reaching, deeply flawed notions about voting. If adopted by the Court, they will provide the rationale for further gutting the Voting Rights Act, as effectively as if it were revoked, and for removing federal courts from virtually any future role in protecting Black voting rights in the US South. These are consequences that could be built on Alito's blatant misstatement of facts and blithe misconception of the history of voting rights struggles.

Justice Alito has sought to overturn the Supreme Court's prior cases about reapportionment and voting rights since he was in the Reagan Administration's Justice Department in the 1980s. In his application for a political appointment as Deputy Assistant Attorney General in 1985, he wrote, "In college, I developed a deep interest in constitutional law, motivated in large part by disagreement with Warren Court decisions, particularly in . . . reapportionment."3Mark Sullivan, Memorandum for Mark Levin, Dec. 12, 1985, https://www.archives.gov/files/news/samuel-alito/accession-060-97-761/Acc060-97-761-box1-Alito.pdf. It was in the same application in which Alito that he stated he was "particularly proud of my contributions in recent cases in which the government has argued in the Supreme Court racial and ethnic quotas should not be allowed and that the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion."

During oral arguments in Merrill v. Milligan, Justice Alito claimed that the current standards used to prove a violation of Section 2 in reapportionment cases were far too easy, allowing Black plaintiffs to win every case or, as he put it, "always run the table" in the South. This assertion is flatly wrong, contradicted by the findings of four noted political scientists who filed a brief in the Alabama case. They told the Court that during the last twenty years, there have been only thirty-one lawsuits claiming dilution of minority voting in the redistricting of the legislative seats of fifty states and 435 Congressional districts. But, only nine of the thirty-one challenges have prevailed in federal courts.4Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, US Supreme Court, Oct. 4, 2022, 105, https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/2022/21-1086_6j36.pdf; Brief of Amici Curiae Jowei Chen, Christopher S. Elmendorf, Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, and Christopher S. Warshaw In Support of Appellees/Respondents, Merrill v. Milligan, July 18, 2022, 7–8, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1086/230239/20220718132621523_91539%20HARVARD%20BRIEF%20PROOF3.pdf. The brief notes that these numbers do not include settlements. Also, the brief reports that earlier in the 1990s 43 Section 2 challenges to district plans involved twenty-two of them in favor of plaintiffs.

Even if Alito and his law clerks had not read the brief, he could not fail to hear Justice Sonya Sotomayor cite the same statistics minutes earlier during oral argument. "Section 2 is not being used that widely," she noted, quoting the brief's statistics as she made the point that cases were brought and won "only in an extreme circumstance where voters are polarized completely and where there's no crossover between the races."5Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, 71–72.

Alito would have none of these facts. He claimed that the current test for proving a Section 2 violation meant Alabama would never win a reapportionment case. "They're not going to win on whether the minority group is politically cohesive. They're not going to win on whether the majority votes as a bloc," he charged.6Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, 105. In other words, Alito contended that Black plaintiffs would always win a case because they always could prove that white voters in Alabama cast most of their ballots as a bloc and that their bloc-voting rarely, if ever, included support for the candidates of Black voters, who also usually voted as a cohesive group.

But, according to Alito, Black plaintiffs ought not win the cases because the bloc-voting by both Black and white people "may be due to ideology and not have anything to do with race. It may be that voters and white voters prefer different candidates now because they have different ideas about what the government should do."7Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, 105. Simply put, Alito suggests it is an ideological, partisan difference, not a racial difference, that can explain why white voters usually reject and defeat the Black voters' candidates of choice in districts where white voters are in the majority.

Alito's observation echoes the outline of an argument that the national Republican Party is aggressively advancing to disable the Voting Rights Act. The National Republican Redistricting Trust (NRRT), the primary Republican organization coordinating national, state, and local Republicans in every state's Congressional and state legislative redistricting, filed a friend of the court brief in the Alabama case. It claims that the Voting Rights Act "intended to equalize minority voting opportunities has instead become a cudgel wielded against any state law that fails to advance the institutional interests of the Democratic Party."8Brief of Amicus Curiae The National Republican Redistricting Trust in Support of Appellants/Petitioners, Merrill v. Milligan, May 2, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1086/222354/20220502163340023_21-1086%20and%2021-1087%20Amicus%20NRRT%20Supp.%20Appellants.pdf.

The NRRT brief cites an earlier lower court opinion from Alabama where US District Court Judge Keith Watkins decided that in the statewide elections for state supreme court justices "factors other than race—most prominently, partisan politics and the decline of the Alabama Democratic Party" explain the election outcomes.9Ala. State Conference of the NAACP v. Alabama (M.D. Ala. Feb. 5, 2020), Case 2:16-cv-00731-WKW-SMD Document 181, 100. The Black plaintiffs lost the case.

Southern Republican leaders are also beginning to parrot this claim. For example, Republican US Representative Troy Nehls of Texas (author of The Big Fraud, in support of former President Trump's claims of a stolen election) recently told the New York Times that the majority of white voters in his Congressional district were not voting against the minority communities' candidate: "These people aren't against brown or Black people. They just don't like the way Democrats are running the country."10Michael H. Keller and David D. Kirkpatrick, "Their America Is Vanishing. Like Trump, They Insist They Were Cheated," New York Times, Oct. 23, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/23/us/politics/republican-election-objectors-demographics.html.

Alito's Republican-inspired argument, if adopted by the Supreme Court, would be devastating to voting rights cases. In 2019 the Court held in a case concerning North Carolina's Congressional reapportionment that federal courts cannot become involved in partisan gerrymandering since it would involve the courts in allocating power among the political parties.11Rucho v. Common Cause. 139 S. Ct. 2484 (2019). An essential part of winning a Section 2 lawsuit against a reapportionment plan requires proving that most white voters in majority-white districts routinely do not vote for the candidate whom Black voters support. In this way, bloc voting by white voters on account of race effectively denies Black voters an equal opportunity to participate in electing candidates to office in violation of the Voting Rights Act. But, if courts begin to decide that bloc voting by whites is based on partisan politics, instead of race, there can be no case heard by the federal courts about voting rights.

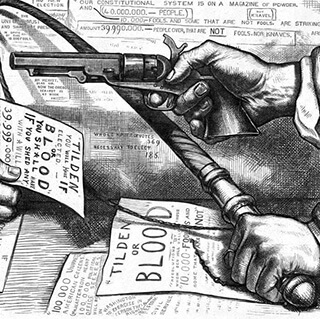

Not even the state of Alabama was brazen enough to make this claim, although it did make its own shameless argument in its brief as to why the Court ought not consider the effects of racial bloc voting. "Racially polarized voting is not state action," the state of Alabama claimed. It is the actions of private citizens and therefore outside the reach of the Constitution which only restricts government actions.12 Reply Brief for Appellants/Petitioners, Merrill v. Milligan, Aug. 24, 2022, 37–38, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1086/234404/20220824160744143_Merrill%20-%20Merits%20Reply%20Brief%20FINAL.pdf. This is an old, discredited notion. Segregationists of the 1940s argued unsuccessfully that the Democratic party's primary elections in the South were private primaries of private political parties, not state action, uncontrolled by the Constitution or the courts. Of course, the Supreme Court flatly rejected that claim since the Court understood that southern officials were using a non-governmental political party's all-white primary as an essential tool in the state government's plan to minimize the impact of Black voting.13Smith v. Allwright, 321 US 649 (1944).

The assertions of the Republicans and Justice Alito are no less ancient and discredited. Southern white leaders have attempted to intimidate, limit, and deny Black people's voting ever since they gained the right to vote because Black citizens have held a different political ideology. In 1867, for example, the first "Alabama Colored Convention" endorsed the Republican party and as new voters proclaimed a political ideology that included "education secured for all; with the old and helpless properly cared for; with justice everywhere impartially administered."14Lucille Griffith, Alabama: A Documentary History to 1900 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1968), 461. The following year, the executive committee of the all-white Democratic and Conservative Party of Alabama announced its opposition to the state's Reconstruction Constitution, which sought the Black Convention's political agenda, which included universal, adult voting and free schools for all children financed by a set aside of one-fifth of the state annual revenues.

The conservative white Democrats insisted, "Color or race has nothing to do with the motive of any one in withholding political privileges." They wrote that it was only because too few Black voters embraced "the science of civil policy to cast an intelligent vote, wisely favor or oppose a legislative measure" that they opposed the new constitution and Black voting.15"To the People of Alabama," Jacksonville (AL) Republican, Oct. 24, 1868, 2.

When conservative whites, including the Ku Klux Klan, burned Black schools and churches in Alabama and across the South during Reconstruction, their defenders claimed it had little or nothing to do with race—only political differences. "As a rule the schoolhouses (and churches also) were burned because they were the headquarters of the Union League and the general meeting places for Radical politicians," wrote Walter L. Fleming in 1905, "or because of the character of the teacher and the results of his or her teachings."16Walter L. Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (New York: Columbia University Press, 1905), 628.

Later, along with other southern states, conservative white Democrats in Alabama disfranchised Black voters in the state's 1901 constitution not merely because they were formerly enslaved Black people. They disfranchised them because Black voters had joined with white Republicans and Populists to challenge conservative white Democratic candidates in pursuit of a different political agenda.17C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), 321–331. Of course, it involved "different ideas about what the government should do" between most white and Black people, and partisan differences. But it was also rank racism.

Similarly, Alabama Governor George Wallace's opposition to Black voting, which eventually helped to enable passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, was based on race, but it also involved a partisan fear that the "bloc vote" (as he called Black voters) would join with a minority of white voters to defeat his political agenda at the ballot box.18Steve Suitts, A War of Sections: How Deep South Political Suppression Shaped Voting Rights in America (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2023).

There is no way to forecast if Justice Alito will attempt to incorporate his Republican-serving rationalizations into the Alabama case or if other members of the Court will follow him in constituting a majority in this case or another. What is clear is that by continuing to dismantle the nation's foremost protections of Black citizens' right to vote and their right to have their votes count equally in election outcomes, a majority of US Supreme Court Justices, often in the name of color-blindness, will be blind to the political history of racism in the Deep South—or will knowingly misconstrue it with an apparent partisan result.

About the Author

An adjunct with Emory University's Institute for the Liberal Arts, Steve Suitts is the author of the A War of Sections: How Deep South Political Suppression Shaped Voting Rights in America (Athens: NewSouth Books, an imprint of the University of Georgia Press, 2023). Earlier in his career, Suitts served as the executive director of the Southern Regional Council, vice president of the Southern Education Foundation, and executive producer and writer of "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," a thirteen-hour public radio series that received a Peabody Award for its history of the civil rights movement in five Deep South cities.

Cover Image Attribution:

Merrill v. Milligan Voting Rights Rally on Capitol Hill, Washington, DC, October 2022. AP photo by Bryan Dozier.Recommended Resources

Text

Anderson, Carol. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Davidson, Chandler, and Bernard Grofman, eds. Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965–1990. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Downs, Jim, ed. Voter Suppression in U.S. Elections. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2020.

Foreman, P. Gabrielle, Jim Casey, and Sarah Lynn Patterson, eds. The Colored Conventions Movement: Black Organizing in the Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

Goldstone, Lawrence. On Account of Race: The Supreme Court, White Supremacy, and the Ravaging of African American Voting Rights. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press, 2020.

Web

"Merrill v. Milligan." Brennan Center for Justice. July 18, 2022. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/court-cases/merrill-v-milligan.

Sanderfer, Selena, Eileen Moscoso, and Rosalie Hooper, curators. Stake Claim or Take Flight: The Birth of Southern Conventions After the Civil War. Digital exhibit. Colored Conventions Project at Penn State University, University Park, PA. https://coloredconventions.org/southern-conventions/.

Stephanopoulos, Nicholas. "The Supreme Court Showcased Its 'Textualist' Double Standard on Voting Rights." Washington Post, July 1, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/01/supreme-court-alito-voting-rights-act/.

Thurgood Marshall Institute at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Democracy Diminished: State and Local Threats to Voting Post-Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder. October 6, 2021. https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/Democracy-Diminished_-10.06.2021-Final.pdf.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Steve Suitts, "Undoing the Voting Rights Act," Southern Spaces, July 12, 2021, https://southernspaces.org/2021/undoing-voting-rights-act/. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Amy Howe, "In 5–4 vote, Justices Reinstate Alabama Voting Map Despite Lower Court's Ruling that It Dilutes Black Votes," Scotusblog, Feb. 7, 2022, https://www.scotusblog.com/2022/02/in-5-4-vote-justices-reinstate-alabama-voting-map-despite-lower-courts-ruling-that-it-dilutes-black-votes/; Merrill v. Milligan, 142 S. Ct. 879 (2022); Shelby County, Ala. v. Holder, 570 US 529 (2013). Steve Suitts, "States Rights Resurgent: The Attack on the Voting Rights Act," Southern Spaces, Aug. 29, 2013, https://southernspaces.org/2013/states-rights-resurgent-attack-voting-rights-act/. |

| 3. | Mark Sullivan, Memorandum for Mark Levin, Dec. 12, 1985, https://www.archives.gov/files/news/samuel-alito/accession-060-97-761/Acc060-97-761-box1-Alito.pdf. It was in the same application in which Alito that he stated he was "particularly proud of my contributions in recent cases in which the government has argued in the Supreme Court racial and ethnic quotas should not be allowed and that the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion." |

| 4. | Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, US Supreme Court, Oct. 4, 2022, 105, https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/2022/21-1086_6j36.pdf; Brief of Amici Curiae Jowei Chen, Christopher S. Elmendorf, Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, and Christopher S. Warshaw In Support of Appellees/Respondents, Merrill v. Milligan, July 18, 2022, 7–8, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1086/230239/20220718132621523_91539%20HARVARD%20BRIEF%20PROOF3.pdf. The brief notes that these numbers do not include settlements. Also, the brief reports that earlier in the 1990s 43 Section 2 challenges to district plans involved twenty-two of them in favor of plaintiffs. |

| 5. | Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, 71–72. |

| 6. | Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, 105. |

| 7. | Transcript of Oral Argument, Merrill v. Milligan, 105. |

| 8. | Brief of Amicus Curiae The National Republican Redistricting Trust in Support of Appellants/Petitioners, Merrill v. Milligan, May 2, 2022, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1086/222354/20220502163340023_21-1086%20and%2021-1087%20Amicus%20NRRT%20Supp.%20Appellants.pdf. |

| 9. | Ala. State Conference of the NAACP v. Alabama (M.D. Ala. Feb. 5, 2020), Case 2:16-cv-00731-WKW-SMD Document 181, 100. |

| 10. | Michael H. Keller and David D. Kirkpatrick, "Their America Is Vanishing. Like Trump, They Insist They Were Cheated," New York Times, Oct. 23, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/23/us/politics/republican-election-objectors-demographics.html. |

| 11. | Rucho v. Common Cause. 139 S. Ct. 2484 (2019). |

| 12. | Reply Brief for Appellants/Petitioners, Merrill v. Milligan, Aug. 24, 2022, 37–38, https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1086/234404/20220824160744143_Merrill%20-%20Merits%20Reply%20Brief%20FINAL.pdf. |

| 13. | Smith v. Allwright, 321 US 649 (1944). |

| 14. | Lucille Griffith, Alabama: A Documentary History to 1900 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1968), 461. |

| 15. | "To the People of Alabama," Jacksonville (AL) Republican, Oct. 24, 1868, 2. |

| 16. | Walter L. Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (New York: Columbia University Press, 1905), 628. |

| 17. | C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), 321–331. |

| 18. | Steve Suitts, A War of Sections: How Deep South Political Suppression Shaped Voting Rights in America (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2023). |