Overview

On October 12, 2020, four Native American scholars, jurists, and activists engaged in a panel discussion (via Zoom) that examined the historical contexts and implications of the US Supreme Court’s McGirt v. Oklahoma ruling, a significant victory for Native land rights. The edited transcript presented here includes a question-and-answer segment from the virtual audience. This panel was made possible through the generous financial support of the Hightower Lecture Fund of Emory University and was co-sponsored by the Native American and Indigenous Students Initiative, Emory's Michael C. Carlos Museum, and the School of Law Health Law, Policy & Ethics Project.

Introduction

Craig Womack: Welcome, everybody, to Atlanta and to Emory University. Welcome to a place where Muscogee Creek people have had government, jurisdiction, and land tenure since time immemorial—way back before the written records. Because this is the heart and soul of where Creek people come from, we feel that this is an important place to have this discussion.

Our panelists include Andrew Adams, currently a justice on the Muscogee Creek Nation Supreme Court. At two different times he's served as chief justice of that body, and he has worked with other tribes, including seven years as chief justice for the Santee Sioux. Justice Adams has also conducted legal work for Chippewa bands in the Midwest. We're glad to have somebody who's in the trenches the way that Andrew is in terms of the matters that we're talking about today. Andrew is a full member of Tvlahasse Wvkokaye Creek Ceremonial Grounds.

The first time I can remember meeting Andrew—and please understand, at this point in my life sometimes the things that I think I remember never actually happened—but my memory of meeting him was at the old location of Tvlahasse Grounds in the mid-1990s. We were the guests of Helen Burgess and Jim Burgess at a Green Corn event that was scantly attended, as far as people in the ring. It was a baptism by fire in the sense that we got thrown into doing a bunch of stuff that a couple of newbies usually wouldn't be doing. I ended up keeping the fire in the ring that night. A year or two later, at that location or at the new grounds site, I got to meet Andrew's dad. Another fond memory.

Craig Womack: Professor Barbara Creel is a member of Jemez Pueblo. Much of the early part of her career, after graduating from the University of New Mexico School of Law in 1990, was in the Pacific Northwest, in the state of Oregon, where she spent seven years as assistant public defender. She was involved in defending reservation residents who were prosecuted under the Major Crimes Act. This is a piece of federal legislation that has a very strong bearing on the case that we're discussing today. She was also a liaison between Oregon tribes and the Army Corps of Engineers whose big water projects often have overlapping jurisdictions with tribes. Professor Creel joined the UNM law school faculty in 2007. She's the former director of the Southwest Indian Law clinic and is now directing her own project on Indigenous innocence, representing Native Americans in post-conviction appeals.

Our moderator this evening is Professor Megan O'Neil, who will be assisting with audience questions after the panel discussion. Professor O'Neil teaches here at Emory and is Faculty Curator of the Art of the Americas. She is a specialist in the ancient Maya and Mesoamerican cultures.

Sarah Deer is in the Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Kansas. Before this, she was a professor of law at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in the Twin Cities for almost a decade where she taught federal Indian law. She's co-authored three books on Native constitutions, tribal legal studies, and tribal criminal law. Her 2015 University of Minnesota Press book, The Beginning and End of Rape, won numerous awards. This area of inquiry is highly significant to our discussion today since the McGirt case not only has to do with tribal jurisdiction, but also with issues of sexual violence.

Professor Deer is a MacArthur Fellow and in the Muscogee Creek Nation. We're very proud of her having captured this award. She's currently the Chief Justice of the Prairie Island (Minnesota) Community Court of Appeals. She was also a judge for three years for the White Earth Chippewa nation, another Minnesota tribe. She's testified before the US House of Representatives, the United States Commission on Civil Rights, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, and many other federal committees and agencies. She has served multiple federal appointments, including chairing the US Attorney General's task force on sexual assault in Indian Country.

The other day I went out to my mailbox. Hope reigns eternal that someday there will be something good in there, and there was! Instead of bills, I pulled out a package from Dustin, Oklahoma. It was from a friend of mine and a friend of Sarah's, Rosemary McCombs Maxey, who's a language teacher, an activist, and a person involved in educating Creek young people. There was a note in the package—Sarah and Rosemary had sewn me a COVID mask out of Creek patchwork. I'm now convinced I have the coolest COVID mask on the planet. It's got this Creek patchwork running down the middle. Now I'm all masked up with nowhere to dance!

I'm going to say a few brief things about Creek history. I've spent a month trying to whittle my comments down to a manageable way of talking about a topic that's very difficult to contextualize in terms of this Supreme Court decision. It requires extensive historical knowledge as well as the need to describe how crimes are prosecuted on reservations. And it involves a complicated narrative about how Oklahoma tribal jurisdiction has a unique status in relationship to other Indian reservations across the United States.

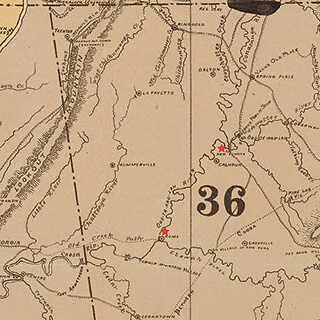

When I've looked at the recent media coverage of McGirt, I've often found it disappointing, even when I read reputable papers like the New York Times. There's no way to fully cover the topics I just mentioned in newspaper articles. You would be hard pressed to cover them in a book, and there is little doubt that books will be written about this decision. My summary is too brief and reductive, but I'm going to flash forward through a huge expansive history. I'm going to skip Creeks as ancient mound builders, skip colonial history and Creek Nation relationships to the English and to the Spanish before them. I'm going to skip the early part of the nineteenth century when Creeks fought a civil war against one another in 1813 and 1814. And I'm going to skip the forcible removal of Indians in 1836 from this very area that I'm speaking from and from other parts of Georgia and Alabama.

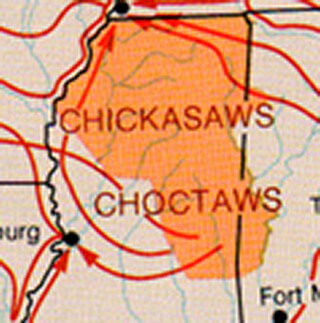

I'm going to fast forward all the way up until the American Civil War when Creeks had barely recovered from the traumatic 1836 removal from Georgia and Alabama. They had suffered loss of life, loss of culture, loss of livelihood, businesses, and farms. They had to start all over. They had to find families to take care of all the orphans whose parents had died during the removal. During the 1860s, when the US Civil War occurred, the official Creek government headquartered in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, sided with the Confederacy. There were a disproportionate number of Creek leaders who had close ties to the Deep South: economic relationships, cultural influences, and, to some degree, plantation systems. Some leading Creek governmental figures were slaveholders. There were also those who had sympathies with the Union. Many of these Creek Union sympathizers fled to Kansas during the conflict. Many Creek men volunteered to join Union forces. The Creek leader Chitto Harjo went to Leavenworth to serve in a Union army unit.

We all know the end of this story. Fortunately, the Confederacy lost the war. Creeks were then forced to renegotiate their treaties with the federal government. They signed the Treaty of 1866, as it's come to be known, which, like most treaties, involved a land cession. One of the things that Creek people had to do was sell a big chunk of the western portion of their lands. The idea being, supposedly, that this area would be used by the United States to resettle other tribes. But the United States also wanted to open it up for eventual white settlement. In spite of having to make that land cession, this treaty made several strong guarantees about Creek sovereignty and jurisdiction into perpetuity in the territory. Because of this, many Creek leaders today regard the 1866 treaty as sort of the gold standard of Creek treaties.

The Civil War was a disaster in Creek country. It split the nation in two. Farms and mills were burned to the ground, infrastructure destroyed. A cholera epidemic ran rampant, killing many. Two decades later, when Creek people had begun to recover from this, they got hit with another disaster for Indian America across the United States. This is the Dawes Act of 1887, federal legislation that forced tribes to allot land that had previously been held in the tribal domain to individual tribal members. The "surplus land" was then opened up to white settlement. This is a main reason that reservations have a checkerboard pattern. Sometimes people think just Indians live on reservations, but because of the Dawes Act, there are also non-Indian residents there.

From Indian Territory's early inception, the United States government set it aside by congressional act as a place for tribes to live and govern themselves. So, the US had to approach the tribes in the Territory—in a way that they didn't have to approach tribes in the rest of the United States—to ask if they would be willing to voluntarily comply with allotment. The southeastern tribes were against allotment and especially against the dissolution of tribal government that was part of the process. The US federal policy idea behind this is that as tribal citizens accepted allotment certificates they eventually would become US citizens and have the same legal status as anybody else in the United States.

If you don't get anything else out of this talk, you can take away the "Native 101" fact that that tribal people, unlike any other minority group, ethnic group, or any other racial group, are defined differently from a legal standpoint in the United States. They constitute governmental entities that have the right to a government-to-government relationship with the United States federal government. With the passage of the Dawes Act, the United States was thinking maybe it could also work itself out of the Indian business, so to speak—which is to say work itself out of the unique status guaranteed to tribes. Sometimes people call this status a trust relationship, not because Indian tribes and the government particularly trust each other, but because of this unique legal standing that involves the right to self-government.

Congress found itself in a bind, having to ask the southeastern tribes, unlike other tribes in the US who weren't located in a special territory, if they'd allot land, if they'd give up tribal government. The tribes said no. Congress, being the entity that passes legislation in relationship to tribes, then flexed its muscles by expanding its plenary powers, the rights it has to pass regulations relevant to tribes, to the nth degree. It tried to make those powers as fulsome as possible by passing the Curtis Act of 1898 which forced the Indian Territory tribes to allot.

One of the things that's really striking about the Curtis Act, from the perspective of someone like me who's not a legal scholar, is that it legislates that the tribes can't have legal representation, can't contest the Act, can't rise to their own defense. With the tribes being forced to allot, the Curtis Act was an assault on tribal government, tribal land, and tribal culture.

After the Dawes Act was passed, then the Curtis Act in Indian Territory, of course tribes didn't disappear. They still organized themselves and formed political entities. After this, the federal government tended to recognize tribal governments on an ad hoc basis. There was a lot of inconsistency. From my perspective, it seemed to work this way: the Bureau of Indian Affairs says, "Okay, here's a tribe that's cooperative. Here's a tribe that opens up its reservation for exploitation of its resources to outsiders; that lets people come in and harvest timber, water, mineral resources, good tribal government, duly elected, we recognize this one." But then there's this other tribal government that's not so keen about letting people come in and take water, timber, and minerals. Then the BIA cries foul, claims this one as bad government they don't recognize, for any number of reasons they create. Since some tribal governments were recognized and others weren't, there was a growing web of confusion with no national template or cohesive policy.

In 1934, Franklin Roosevelt appointed John Collier to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Collier, a much more progressive leader than his predecessors, successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Indian Reorganization Act. This legislation, often called the "Indian New Deal," allowed tribes to form constitutions if they chose to do so, to submit them to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for approval, and, if they were approved, then they were allowed to form governments that the United States would recognize.

I'm going to leave it at that. The panel can correct my mistakes and I will not be offended. Sarah is going to describe how the status of the Creek Nation has changed since the July 9, 2020, McGirt Supreme Court ruling. Then we'll see what other panelists want to say.

Panel Discussion

Sarah Deer: Thank you, Craig, for that great introduction and thank you all for inviting me to be part of this panel. As a Creek citizen, this is a case that will have deep meaning for us for many years to come. And as a disclaimer, I'm here today in my personal and academic capacity. Because I also advise the Creek Nation, I want to clarify that I don't speak here in any official capacity, on behalf of the Nation.

I want to make sure as we discuss this case that you've got the basic facts. We're talking about two cases here, but the one that counts is McGirt v. Oklahoma, which was argued online due to COVID-19. We could all call in and hear the oral arguments—we're not used to that. Most of the time you have to go in person.

The decision was released in July on the very last day that decisions were announced. I think it's clear that this is one of Justice Ginsburg's final, if not the final, votes of her tenure on the Court. It's interesting that we focus on reservation law with this case, but actually both of the cases at issue here began as criminal cases. I'm glad that Professor Creel is on our panel because she'll have some more insight into the work of how criminal defense attorneys think about reservation issues.

But there were two cases. There was a case involving Patrick Murphy (Sharp v. Murphy), who was convicted of homicide and sentenced to death by the state of Oklahoma. And then the case's (McGirt v. Oklahoma) namesake here, Jimcy McGirt, a Seminole man who committed some heinous sexual crimes on children and received a draconian one thousand years in Oklahoma custody. So, these are two men that had very little to lose by appealing their decisions. When you're on death row, you've got attorneys who are trying any way to save their client's life. And from Mr. McGirt's standpoint, there was not a lot to lose by challenging jurisdiction. But both of these men, and even the state of Oklahoma would agree, committed their crimes within the boundaries of the 1866 reservation that Craig discussed.

From the perspective of a criminal defense, the fact is that if this is an Indian Reservation, if it still exists, then these two men were prosecuted by the wrong government. Under the Major Crimes Act, the federal government has criminal power over lands considered Indian Country and the state does not. So their argument on jurisdiction hinges on the question of whether or not the 1866 treaty is still the standard by which we assess Creek territorial jurisdiction. There were other cases that came before this, that did not have to do with the Creek Nation but answered a similar question: Is the reservation still there or not? Do the boundaries still apply or not? And the rules that the Court has created over the years require that Congress explicitly change the governing territory of the tribe. There were two other cases in the last thirty years in which the Court held that only Congress can establish a reservation and it cannot be inferred. It has to be explicit.

Attorneys for Murphy and McGirt argued that the defendants were prosecuted by the state of Oklahoma, which did not have jurisdiction over them. Now Craig did a great history here, so I don't need to go through all of this, but it was in 1866 that this treaty was signed. And really the language of the treaty that I think Justice Gorsuch focuses on in his written decision is the very clear language that this land—and again, there was half of it ceded in 1866—would be forever set apart as a home for the Creek Nation. And this is consistent with the other treaties that the Creek Nation had signed, even those prior to removal. So the language was consistent—words like "forever" and "perpetuity" are important for the contemporary interpretation.

What Justice Gorsuch did in McGirt was write the official decision on behalf of the majority. It was a five-four split. Writing for what people characterize as the liberal arm of the bench, Justice Gorsuch determined that because there had been no explicit language by Congress, despite allotment, despite demolishing tribal courts, despite all of those things which Oklahoma certainly argued, there was never a clear disestablishment of the reservation by Congress. Therefore, the 1866 reservation still exists. Therefore, McGirt and Murphy were prosecuted by the wrong government.

The Creek Nation and other amicus clients filed briefs in this case, and the ultimate outcome was one of victory—not just for these two criminal defendants, but for the Creek Nation and potentially many other nations. Justice Gorsuch writes that on the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise, and "because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word."

I want to share two more quotes from McGirt to emphasize how emotional this decision was for many of us. It felt like it set things right for the first time in a long time. One of the passages I so admire from this decision is that "Congress may sometimes wish an inconvenient reservation would simply disappear. But wishes don't make for laws." These kinds of principles transcend Indian law and speak to what justice really is about.

Justice Gorsuch also writes, "None of these moves by Oklahoma would be permitted in any other area of statutory interpretation and there is no reason why they should be permitted here. That would be the rule of the strong, not the rule of law." And finally: "Unlawful acts performed long enough and with sufficient vigor are never enough to amend the law. To hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right."

Because today is Indigenous Peoples' Day, this particularly resonates with me. It isn't just about this Creek tribe and this Creek reservation. It's about a justice of the Supreme Court acknowledging the harms that were done and fighting for justice today.

So now we have a reservation. We always had one, but now it's recognized again. And what that means is that our territorial reach as a nation is far further than we have been exercising it. The Creek Nation now has full territorial reach throughout the boundaries of the 1866 reservation. Which is about a twelve to thirteen county area, including a great deal of the city of Tulsa. We are now tasked as a nation with governing that reservation and with the challenges posed by a large expansion of recognized territorial reach. But these are challenges that the Creek Nation is ready to take on.

Prior to McGirt, the Creek Nation had what we call Indian Country, a legal term of art referring to land that's been in trust or has a restricted status, owned in fee by the tribe—plots of land, whether they be former allotments or contemporary business district holdings. That was it. That was Indian Country. Once you step off that plot of land into the state of Oklahoma, then the state would no longer recognize you as being in Indian Country. But one of the definitions of Indian Country is all lands within the limits of any Indian reservation. So if the reservation still exists, our authority in terms of criminal law doesn't just rely on a particular plot of land; it's going to be anywhere within the boundaries of the reservation. This is a dramatic increase in recognized territorial authority.

Craig Womack: Professor Creel do you have anything you would like to add?

Barbara Creel: Yes, thank you for inviting me. Happy Indigenous Peoples' Day. Know that you are on Native land that was inhabited before contact, before the white settlers came. The McGirt case is one of the most important Supreme Court cases in land acknowledgement.

As far as background to McGirt, I wanted to add a couple of things. Professor Deer mentioned Sharp v. Murphy which started out in the Tenth Circuit as Murphy v. Royal and percolated up to the Supreme Court. It was argued and set for re-argument, but it was going to be a four-four split because Gorsuch had recused himself. You see, the decision was a Tenth Circuit decision from when he had been on that court. He didn't write that decision, but it wouldn't be proper for him to weigh in on it from his new position on the Supreme Court.

McGirt didn't change the status of the Creek Nation or expand tribal jurisdiction. McGirt recognized that the tribe had ancestral lands that were documented in treaties and congressional enactments. Federal criminal jurisdiction versus tribal jurisdiction versus state had been established in the 1883 case of Ex parte Crow Dog, which led to the Major Crimes Act of 1885. So, as Professor Deer said, if it was Indian Country and a murder after 1885, the case would be prosecuted in federal court.

Craig Womack: Along the lines of talking about ideas that came out of the 1883 case, I want to ask a question. And this very much comes from the perspective of someone whose head swims when hearing legal history. (Mainly I write novels and I play the fiddle.) But my question is this: since the McGirt decision recognizes Oklahoma tribes as having reservation status, does this ruling simply catch up Oklahoma tribes to the rest of Indian Country—much of which has had reservation status for a century now—or does it do something more?

Andrew Adams III: I guess I'll jump in quickly. First of all I thank Craig and Emory University and everyone that put this together. And I will give the same disclaimer that Professor Deer offered: I'm here speaking in my own personal, individual capacity. But to quickly answer your first question, Craig. I approach it from the standpoint that the status of the tribe didn't change, but the status of the law and essentially the federal government's posture and position related to the Muscogee Nation, changed.

The Muscogee Nation didn't change. But if you think about it in very practical terms, before the McGirt decision was issued, the Department of Interior didn't have to recognize or give any credence to the reservation boundaries. But after the Court issued its decision essentially reaffirming—and I say "reaffirming" because I don't like the terms "recognized" or "reestablished." Those reservation boundaries never went away. I can remember my first year of law school at the University of Tulsa in 2003 sitting in Professor Rice's office (whom I affectionately call Uncle Bill) and him saying, "Nephew, your tribe's reservation, you're sitting on it. You're living on it right now." I had always heard these stories about the reservation going away and he said don't believe any of that. "Congress is the only entity that can take away or diminish a reservation. And by golly nephew, when you moved down here from Michigan you moved onto your homeland."

And so when the decision was issued, it struck me emotionally. I already knew that Uncle Bill was one of the smartest people I'd ever met. But it just drove that belief further home that nearly twenty years ago, Uncle Bill—and not only Uncle Bill, but also one of the colleagues that I have on the Supreme Court, Justice Leah Harjo-Ware, when she was the attorney general for the Muscogee nation years ago—that nearly twenty years ago he made those same arguments.

There are a lot of Muscogee people who have walked with that belief close to their hearts and minds.

Then to answer your second question, Craig, the existence and disputes and concerns about reservation boundaries permeate across Indian Country. There are a number of tribes that either are in some type of dispute with, say, a county sheriff over who has jurisdiction over what people over what geographical area, or they could be in federal district court, or in some type of court of appeals where they're trying to press their case as to why the boundaries that are identified by the federal government or a state government or some subdivision of a state government are not correct.

I believe that what McGirt has done for Indian Country is to reaffirm all of those decisions in the past like Solem v. Bartlett and Hagen v. Utah where Congress is the only entity that can diminish or disestablish a reservation. And you actually see just in the time since McGirt was decided, a positive cascading effect on other federal courts, where they have provided some favorable decisions for tribes. As an Indian law practitioner and someone who, when I wake up in the morning, kind of feels like Luke Skywalker—that I fight for the good guys, that I represent tribes—I hope that continues. I hope that various levels of government get to the point where they do have that respect for tribal homelands.

Craig Womack: Thank you, Andrew. Do other panelists want to join in this discussion about reservations status?

Sarah Deer: There's been a lot of backlash from both state officials and the general public in Oklahoma, whom I don't think fully understand what McGirt means. No, it does not mean that five tribes own the east half of Oklahoma as it's somehow been suggested. Nothing changes the status of the land within the reservation. If you own a home in Tulsa or Glenn Pool, nobody's going to take that home away from you. If you're a private business and you have your business on the reservation, the status of the land where you run your business does not change. What it changes, though, is the extent to which the tribe's sovereignty is matched in the territory that it exercises; the Creek Nation has more options for exerting governmental power now. But in no way does it does it take somebody's land away or take their livelihood away. And I think that's been misrepresented in the press quite a bit.

Craig Womack: A lot of what we have heard and read about has focused on the tribe having increased jurisdiction over criminal cases. It's being depicted as an advantage. But we have also heard about the tribe now having more cases to take care of than ever before, and some have said, the situation may be overwhelming to the extent that there may be a need for expansion of the tribal court system. I was thinking when I listened to Professor Creel's podcast, which is really excellent, about her insights into the Major Crimes Act and how this act is still imbued with a colonial viewpoint. So are there other advantages, or any disadvantages, to be considered?

Sarah Deer: I'm going to let Professor Creel answer the crux of that, but yes, again, a lot of people don't realize that, technically, tribes retain concurrent authority over felonies on reservations. That's misunderstood when people read the Major Crimes Act as though it was a grant of exclusive jurisdiction to the federal government. Tribes in some states, not all, prosecute homicide, rape, and child sexual abuse, but by and large, when we think about those kinds of crimes on reservations, we think about them "going federal"—so the US attorney's office becomes involved. But certainly the tribe can also independently exercise that kind of criminal authority. To the extent that one would calibrate justice for victims with more tribal prosecution, the tribe is now in a position to do that on a much grander scale. But it does require additional staffing to be able to govern that big of a stretch of reservation. In terms of the criminal defense perspective, I'd like to ask Dr. Creel.

Barbara Creel: Thank you, Professor Deer. I would like to hear from the tribe about advantages and disadvantages, but I know from my criminal law teaching that sovereignty is what sovereignty does. As a sovereign, the tribes have incredible power to shape their own justice systems. I teach the differences between the American cultural and moral values and Indigenous cultural values and rely heavily on Sarah Deer and Carrie Garrow's book, Tribal Criminal Law and Procedure, in which they discuss where tribes get their inherent decision making about what wrongdoing is and how to punish it. How do sovereigns address wrongdoing in their own jurisdiction? It's powerful to think about. We could start over, right? We could be a Crow Dog nation that looks to restorative and rehabilitative justice instead of retribution.

We all know that the first thing we hear on Indigenous Peoples' Day is the parade of horrible statistics that Native Americans are subjected to. This case provides opportunity for the defendant who was a community member and the tribe to be on the same side. That does not happen in Indian Country cases. It's usually the United States acts as a punisher and the tribe acts as a punisher. But at this point, the two interests converge between the individual defendant and the tribe. I think it promotes what I teach: tribes are made up of individuals. What I was taught from my family values is that the people are the heart of the tribe. The tribe is the body and the people are the heart.

The advantage is having tribal sovereign government rethink its criminal jurisdiction and do differently than what the adversary system has imposed upon us. The disadvantages in this line of thinking are what Professor Deer mentioned: we're so far behind in resources in our own justice systems because they were taken away or encroached upon due to the Major Crimes Act.

We are impoverished in the ability to think and rethink about justice. I've taught tribes how to look into their own history to decide how to move forward. This was a foreign concept, either because the state took over after termination or because of the Major Crimes Act. But because of this rule of history that Gorsuch mentions—this is always the way we've done it, so we're going to keep doing it that way—tribes have lost their own thread of thought in how to treat wrongdoing. They've been without resources and basic governmental functions.

Andrew Adams III: When you think about federal policy related to Indian tribes over the last two hundred years, it's gone through different themes. Since the Indian Self Determination and Educational Assistance Act, the federal government has been in this mindset of self-determination—that tribes should be self-determining in expanding their sovereignty. So the biggest advantage that I see from McGirt is that the decision opens up a lot of options for the Muscogee Nation to expand and mature its jurisprudence. It expands the different types of cases that can come before the Muscogee Nation courts. I believe that the volume will increase and with that more opportunities for the courts of the nation to issue decisions that further the maturation of Muscogee case law.

Craig Womack: Thank you, Andrew. I want to ask one more question of Sarah, and of course anyone else can weigh in on this. Since McGirt has to do with tribal jurisdiction and sexual violence, can you address these two topics in relation to one another?

Sarah Deer: Certainly. What's interesting about this case is that I worked with a Cherokee attorney named Mary Kathryn Nagle, and we've been filing amicus briefs in Indian law cases for the last five or six years. We feel like the voices from Indian Country of victims of crime are not often presented to the Court. We did that in McGirt and in Murphy. Our primary client was the National Indigenous Women's Resource Center, a large national Native nonprofit that's dedicated to ending violence against Native women and children. We argued on behalf of McGirt and on the side of the tribe that these cases belong in tribal court. To the extent that we have strange bedfellows, I think it's worth noting again that this idea of sovereignty matters for victims and sovereignty matters for defendants. Tribal nations are in the best position to make decisions about how to protect people and hold people accountable. It may seem ironic that a victims' rights organization would side with somebody alleged to do some pretty horrific things, but the end goal of making sure that tribal nations are strong and capable of protecting one another is at the core of what any sovereignty battle is about—the battle to define what's right and wrong and how we resolve those questions.

Barbara Creel: That's Indian law, right? We're a unique, interesting, quirky, crazy quilt of jurisdiction. I wanted to add another point with regard to disadvantages. Tribes have the power to adjudicate criminal acts on the reservation. Because of separate sovereignty and the dual sovereignty doctrine, a Native American can be facing up to a year in jail without the benefit of counsel. Natives are the only people that that happens to in the United States. We're the only ones that can go to jail without an attorney. Natives are also subject to double jeopardy because they can be prosecuted by their own tribes and by federal court under the Major Crimes Act. The problem of over-policing and over-criminalizing and over-incarcerating Native Americans has a long legacy. In footnote six of the McGirt decision, the Court says some helpful things about land recognition and Native rights and points to the Pueblo Indians in the case of United States v. Sandoval. But that 1913 case was one in which the Supreme Court was trying to decide who was an Indian, and whether Pueblo Indians were Indian because there was no definition. What did the Court look to determine whether Natives were Indians? Behaviors and stereotypes. They decided that Pueblo Indians were dimwitted, had plural marriages, practiced non-Christian religions, and were in need of guardianship. That's the legacy that continues to thread into these 2020 cases. We're still carrying around those labels.

Craig Womack: Thank you. We're going to move to questions with the help of Dr. Megan O'Neil, assistant professor of art history at Emory University and faculty curator of the Art of the Americas at the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

Question and Answer Session

Megan O'Neil: Thank you, Craig. The audience has posted many questions, which I think speaks to how important this work is.

First I want to read a comment from an attendee, Stuart Fenton: "The language used by Justice Gorsuch was beautiful, brings tears to my eyes, even though I'm not Native. I'm a lawyer, however, and Jewish so I understand deeply the wrongs done to your people; similar wrongs have been done to mine."

How about the more general question about the implications of this decision in Indian Country outside of the Creek Nation?

Sarah Deer: I think the way in which Gorsuch challenges the other justices to confront the ugly history of federal Indian law and to look at what really happened on the ground could have impact on cases involving tribes that have related concerns about questions of self-government. His ability to look and be honest about the history is, I hope, a template for justices ruling on Indian Country cases in other contexts.

Megan O'Neil: Here's a question regarding what's written in the McGirt majority opinion, that there is no reason why Congress cannot reserve land for tribes in much the same way, allowing them to continue to exercise governmental functions over land even if they no longer own it commonly. How would such a conclusion affect the outcome of Alaska v. Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government, et al. from 1998?"

Sarah Deer: Venetie is a devastating case out of Alaska. It actually came out when I was a law student. It made me wonder why I was in law school, it was so poorly reasoned. But it's a question of tribal territory, really a different animal, because it's looking at the Alaska Native Claim Settlement Act, which is not applicable in the lower forty-eight and certainly not in Oklahoma. So, I would love to see Venetie reconsidered, but I'm not sure McGirt really changes anything as far as that decision goes.

Barbara Creel: I agree. Venetie was looking at the definition of Indian Country and deciding whether the Alaskan Native corporations fit within one of those definitions and found that they did not.

Megan O'Neil: Here's a question from Sarah Hill asking if you could comment on the response to the decision by the Cherokee Nation and the state of Oklahoma.

Sarah Deer: Well, the state of Oklahoma is pretty unhappy, and that's been expressed by a number of state officials, including the attorney general, who referred to us as "sovereignty hobbyists" in one of his disparaging comments about our efforts to expand tribal authority. I can't speak to the Cherokee's official position or not. Each tribe is unique and different.

Megan O'Neil: This next question is for Justice Adams, from Veronica Passfield: "After attending graduate school with Andrew I moved to Oklahoma City. Governor Stitt created a committee to strategize about how to adapt to McGirt. His committee included oil and gas CEOs, but no tribal leaders. I'd like to hear thoughts on McGirt backlash and how the community can advocate to help offset it."

Andrew Adams III: It's appropriate that we're having this conversation on Indigenous Peoples' Day. The parade of horribles you hear from individuals, from the state attorney general and Senator Inhofe, claims that the Supreme Court is creating an untenable situation in Oklahoma where the Muscogee Nation is going to be able to exercise "enhanced jurisdiction" or "extra jurisdiction" over its reservation. People say that the sky is going to fall if you give these Indians authority over their land again.

A lot of people, when they think about reservations and about treaties, think about the United States saying, "Okay, we're going to give you this land." But there's another way of thinking—and there's power in words—that reservations are the land that the tribes reserved for themselves. It wasn't anything that was given to the Muscogee Nation. This was land that the Muscogee Nation saved for itself as a homeland in exchange for other rights. Anyone who predicts the sky is going to fall, they are perpetuating the settler mentality imposed upon Indian peoples. The US Supreme Court did the right thing by issuing this decision. And now let the state of Oklahoma and the Muscogee Nation work as sovereigns.

Megan O'Neil: This next question is from Sarah Armstrong, a current public defender in Atlanta, a University of New Mexico alum, and a former student of Professor Creel. "What advice can you give to non-Native defenders of Indigenous rights, especially with respect to this decision?"

Barbara Creel: Every time I work with a person from a different family, a different community, a different tribe, a different government, I treat that experience as one of an ambassador. Learning about the particular tribe. I teach the way to be an ally is to promote Indigenous wisdom and Indigenous voices. Learn about the ancestral lands which you are standing on right now and elevate the voices of Native people. Educate yourself but know that each tribe is different. There is no pan-Indian way. Combat willful ignorance. Don't give up because these issues are complicated. Be willing to fight those injustices where you see them.

I appreciate the work of the Indigenous Women's Network and of all those who come to these issues with their own wisdom and with the experiences of having lived through violence or the criminal justice system or being court-involved.

Megan O'Neil: The next question is for Professor Deer, regarding sexual violence law jurisdiction in Indian Country: "How do you hope the case against McGirt and other cases of sexual violence committed in this region will be pursued? How does the Violence Against Women Act come into play, and how might the Creek and other Native nations bring Indigenous perspectives to such cases?"

Sarah Deer: Thank you for the question. Yes, Mr. Murphy and Mr. McGirt have both been indicted in federal court, which was the appropriate court that should have had their case from the beginning. While some headlines suggested that McGirt is leading to the release of dangerous persons, the reality is that McGirt and Murphy are still under the jurisdiction of the United States and are going to either plea or be prosecuted by the US attorney. So as far as they're concerned, the question might be, "Could the tribe also prosecute them under concurrent authority?" Certainly, going forward, the Creek Nation has a homicide law. It has a rape law. It has a child sexual abuse law, a child pornography law. So, the Tribal Council, the legislative branch of the tribe, has passed laws which suggest that the government would like to see authority in those cases. Only time will tell. I do think that the tribe has the potential at this point to take other kinds of crimes under tribal law. That'll be an interesting development, and as Professor Creel noted, we're not necessarily wedded to the Western law-and-order model. We can create therapeutic models of justice. Many tribes have done that. It's a very interesting time to be Creek.

Megan O'Neil: "The Supreme Court has not ruled on whether the Major Crimes Act divested tribes of jurisdiction, but it's widely accepted now that it did not. However, there's contrary language in some Supreme Court decisions. As I read the Gorsuch opinion, it doesn't have any definitive language suggesting he views the Major Crimes Act as divesting tribes of power, but there's some language that could be read as suggesting he assumes it did. Can you say anything about whether or how the opinion might affect tribal jurisdiction over major crimes or how the tribe might be approaching the question?"

Barbara Creel: That sounds like Professor Rolnick.

Sarah Deer: Thanks, Professor Rolnick, I'm sure we can write a law review article on this question at some point. I think any reference to whether the tribes retain jurisdiction or not in Gorsuch's opinion is a matter of dicta. Of course, you know, I think the reasoning that only Congress can divest tribes of jurisdiction would apply here. That the Major Crimes Act did not divest—there's no explicit language in the Major Crimes Act divesting tribes of jurisdiction. But yes, you're right. The question is not definitively answered in the Supreme Court at this time, but I feel confident that using this kind of case as a precedent will aid that if it does come before the Court at some point.

Barbara Creel: I read the opinion, too, with Gorsuch saying that the Major Crimes Act encroached upon tribal jurisdiction, but it was a limited encroachment in that it was specific enumerated crimes. It's widely accepted that there's concurrent jurisdiction because of Supreme Court decisions that say the dual sovereignty doctrine applies. I think that there have been implications that both the tribe and the feds have jurisdiction.

Megan O'Neil: Here's a general question about Muscogee Creek language: "As someone who was born and raised in Bogotá, Colombia, currently living in Massachusetts, I advocate for linguistic human rights being a native Spanish speaker. And I'm wondering if any of the scholars in the panel know about laws regarding language access or language advocacy, not just for the Muscogee language or the Creek people, but any of the hundreds of Indigenous languages in the United States."

Craig Womack: I'm not sure I can answer this question. For a long time, Sarah and I were in a group that got together to speak Creek with our mentor Rosemary McCombs. One of the things that Sarah was always interrogating was whether or not there are certain Muscogee words or ideas that had to do with legal principles. So, Sarah, did you want to say something about this? You can answer it better than I can.

Sarah Deer: I have to admit, that while I am a language learner, I don't know much about any federal or governmental policies about promoting language per se. I tend to focus my scholarship in the criminal arena, but there are people actively trying to save the Creek language today. It is an endangered language. We do have a linguist that committed himself to our language. His name is Jack Martin at the College of William and Mary. He co-authored our dictionary and grammar book. It is always an ongoing process to save an Indigenous language and our tribe does have a language department and there are a couple of colleges in Oklahoma that teach Muscogee language. But beyond that, I don't know that I have a lot of knowledge to bestow.

Craig Womack: I don't know of any state that has recognized a Native language as an official language.

Barbara Creel: New Mexico's constitution guarantees access to the courts in additional languages besides English. That means Spanish and Native languages. Because of the Major Crimes Act, Native language certifications are really important. States with large Native populations or states that care about Native citizens can pass a statute with regard to language access in the court system simply on a due process basis. The Pueblos come at it from a little bit different viewpoint in that my tribe has language immersion at Head Start. Language is spoken in the home and in intergenerational daycare. There's also a lawsuit in New Mexico suing the state department of education for lack of language access and services for Navajo and Pueblo speakers.

Andrew Adams III: I'll just quickly add that there are tribes all across the country that have passed tribal laws concerning traditional and Indigenous intellectual property protections. Often, tribes will identify their language as being part of that corpus of information that they consider that needs to be protected and archived and will actively budget funds for that protection, not looking to the state or the feds.

Barbara Creel: In my tribe, there is a rule against sharing the language because Pueblo language is not for public consumption. You don't find it taught in community colleges as you do in other tribes. It exists for internal purposes and is imbued with concepts that shouldn't be shared with others. The tribal language provides a different function than English does.

Megan O'Neil: Thank you so much. Here's a question from Ed Barker who's asking if McGirt affirms Congress's power to extinguish Indian Country. What do you all think about that question?

Andrew Adams III: From my standpoint, McGirt does essentially prop up the legal concept, the plenary power over tribes, right? That Congress, if it wants to, can pass statutes that dramatically change the legal relationship between the United States and federally recognized Indian tribes. And in this current environment, in some respects I don't mind that.

Sarah Deer: I agree, and I think that's been a big critique, especially by scholars who raise the question, "Is this really a victory if it continues to recognize Congress's plenary power?" In response to that, I'm not sure we will ever have that victory in the Supreme Court. What's important to note about this question is that tribal interests have had a much better go of things working with Congress than working with the courts. We tend to lose in the federal courts quite a bit, but yet we've managed to sustain some pretty progressive legislation in Congress. So if Congress is the place to go, I feel like the political process offers more ways to pursue tribal interests. We don't have control over the litigation that comes up about our sovereignty within the federal courts. But I don't think at this day and age, you would see a complete repudiation of Congress's plenary power, but one can always hope, I suppose.

Sarah Deer: I've written on tribal law, but primarily on violence against Native women. And because I get asked a lot, I finally made a website where you can find my writings at SarahDeer.com.

Barbara Creel: I'll also recommend the Sarah Deer, Carrie Garrow book that I mentioned before, Tribal Criminal Law, as a ready resource for people that just want to understand criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country with really good examples of Native thought in criminal law.

Conclusion

Craig Womack: This has been an amazing discussion. Not only for those of us on the panel, but for the impressive level of experience of the audience—people who went to law school with, or are former students of a panelist, academics such as Sarah Hill, who've written about southeastern people, grassroots people doing work in Creek country, law students across the country, law professors. And all the other members of the audience who have listened in. I'm excited too about the potential, as Professor Creel said, of being able to do things differently and maybe to expand into more ways of looking at restorative justice and creative approaches to governments and alternatives to punitive-based approaches to criminal justice. It's exciting to think about where this might lead us. Cehecvres, see you all again.

About the Panelists

Andrew Adams III is a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and member of the Tvlahasse Wvkokaye Ceremonial Grounds. He currently serves as Justice of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Supreme Court, Chief Justice on the Santee Sioux Nation of Nebraska Supreme Court, and Justice on the Gun Lake Tribal Supreme Court.

Barbara Creel, a member of the Pueblo of Jemez, is a professor of law at the University of New Mexico School of Law and former director of the Southwest Indian Law Clinic.

Sarah Deer is a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma and University Distinguished Professor at the University of Kansas. She holds a joint appointment in the Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and the School of Public Affairs and Administration. Professor Deer is also the Chief Justice for the Prairie Island Indian Community Court of Appeals.

Craig Womack is an Oklahoma Creek-Cherokee Native American literary scholar, writer, and teacher, and an associate professor of English at Emory University.

Recommended Resources

Anderson, William L., ed. Cherokee Removal: Before and After. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

Banner, Stuart. How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

Garrison, Tim Alan. The Legal Ideology of Removal: The Southern Judiciary and the Sovereignty of Native American Nations. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Garrow, Carrie E. and Sarah Deer. Tribal Criminal Law and Procedure, 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Littlefield, Daniel F. Jr. and James W. Parins, eds. Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Imprint of ABC-CLIO, 2011.

Richland, Justin B. and Sarah Deer. Introduction to Tribal and Legal Studies, 3rd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Web

"Home." Tribal Court Clearinghouse. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.tribal-institute.org/index.htm.

Reese, Elizabeth. "Welcome to the Maze: Race, Justice, and Jurisdiction in McGirt v. Oklahoma." The University of Chicago Law Review Online. August 13, 2020. https://lawreviewblog.uchicago.edu/2020/08/13/mcgirt-reese/.

"Tribes, Tribal Organizations, and Tribal Public Health." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last reviewed December 21, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/tribal/tribes-organizations-health/tribal_groups.html.

"Welcome." Sarah Deer: Tribal Legal Scholar. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.sarahdeer.com/.

Zardo, Maria Noel Leoni. "Gender Equality and Indigenous Peoples' Right to Self-Determination and Culture." American University International Law Review 28 no. 4 (2013): 1053-1090. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1755&context=auilr.