Overview

On July 1, 2021, in the case of Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, the Supreme Court issued eighty-five pages of opinions concerning a new interpretation of a 1982 amendment to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Steve Suitts, who was involved in the Congressional hearings and debate that led to the renewal of the Voting Rights Act in 1982, provides this primer on what the majority opinion holds, its contradictions and shortcomings, and its dangerous implications for voting rights.

Blog Post

In a 2021 case from Arizona, Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., issued an opinion of the US Supreme Court—calling it a "fresh look"—that sabotages Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In effect, he rewrites the amendments Congress adopted in 1982 and annuls their purpose of making it easier, not harder, to strike down voter suppression laws resulting in racial discrimination. The Court's decision will likely unleash a new round of widespread discrimination in voting across the nation and continues its section-by-section destruction of the law that has been the nation's most effective force for expanding democracy over the last 150 years.

The Court decision reveals again that on matters of race and racism, when it suits their agenda, Justice Alito and the current Court's majority will abandon their own "textualist" judicial philosophy of adhering to the text of a law. Those studying this opinion will find it difficult to believe that it was written by the judge who, on and off the bench for years, has declared, "Statutes mean something. And the role of a judge is to interpret and apply the laws as they are written. . . . That's what we mean when we say that we have the rule of law and not the rule of men."

In his majority opinion, written for the six members who comprise the Court's conservative wing on controversies of race, Justice Alito upholds Arizona law that invalidates a voter's entire ballot if it is cast in the wrong precinct for any reason (even if the mistake is the fault of a voting official), and prohibits civic groups from collecting sealed ballots. Alito's opinion damages the ongoing protection of voting rights across the nation. It creates a list of standards that federal courts should consider when applying Congress's 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act's Section 2—the section that permits federal lawsuits challenging voting discrimination across the country. These Congressional amendments overturned a 1980 Supreme Court opinion that a law violated the Act only if intent to discriminate could be proven. Congress's amendments provided that, after considering a "totality of circumstances," a federal court need only find that a law or practice has a discriminatory result.

The US Senate's report explaining the Act's 1982 changes stated:

The courts are to look at the totality of the circumstances in order to determine whether the result of the challenged practice is that the political processes are equally open; that is, whether members of a protected class have the same opportunity as others to participate in the electoral process and to elect candidates of their choice. The courts are to conduct this analysis on the basis of a variety of objective factors concerning the impact of the challenged practice and the social and political context in which it occurs. The motivation behind the challenged practice or method is not relevant to the determination.1Voting Rights Act Extension, Report of the Committee on the Judiciary, Unites States Senate, on S. 1992, 97th Congress, May 25, 1982, 67.

Justice Alito's opinion lays out five "guideposts," his own version of the "objective factors . . . and the social and political context" that lower courts should consider. He describes these new standards as the Court's "logical" definition of what Congress meant when they instructed federal courts to consider a "totality of circumstances" in Section 2 cases:2The order in which Justice Alito listed his "guideposts" has been slightly altered here. I list his third item second for purposes of analysis.

- "size of the burden imposed" on the protected group;

- "size of the disparity in a rule's impact on members of different racial or ethnic groups";

- "degree to which a voting rule departs from what was standard practice" when the Congress added the term "totality of circumstances" to the law in 1982;

- "opportunities provided by a State's entire system of voting when assessing the burden imposed by a challenged provision";

- "strength of the state interests served by a challenged voting rule."

These standards are not found in any official reports of the US House or Senate issued in 1982 as the Congress debated and renewed the Act with amendments. None are mentioned as recommended standards in the extensive testimony during Congressional hearings in both Houses.3See Hearings before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Judiciary Committee, House of Representatives, on H.R. 1407, H.R. 1731, H.R. 2942, H.R. 3112, H.R. 3198, H.R. 3473, and H.R. 3948, 97th Congress, May 6, 7, 13, 19, 20, 27, 28; and June 3, 1981; Report of the Subcommittee on the Constitution of the Judiciary Committee, United States Senate, 97th Congress, on S. 1992, April 1982. They are merely "logical" products of Justice Alito's thinking after conferring with his law clerks and perhaps some of the Court's other conservative members.

The most striking feature of Alito's "guideposts" is that they all offer ways to make it more difficult for a person to prove a voting rights infringement. The 1982 amended statute does not say that a "totality of circumstances" should include only considerations that make it more difficult to prove a case. On the contrary, the law was written to make it easier to prove discrimination. The Senate report mentions only that the "extent to which members of a protected class have been elected to office in the State or political subdivision is one 'circumstance' which may be considered." So, the Congress listed a consideration that can help prove a violation of the Act.4The legislative history does make it plain that the "result" test has limits. It does not guarantee a right to proportional representation. Quite the opposite, Justice Alito's list imposes on the statute five considerations that will be used primarily to disprove a violation.

For instance, Alito lists the "size of the burden" as a consideration instead of "if a burden is created," which would have been a neutral standard—e.g., does the rule create a burden to a protected group? Alito's second point similarly mandates consideration of "size of the disparity in a rule's impact on members of different racial or ethnic groups"—not if a disparity exists, but how large the disparity is. In this way, the opinion suggests that the size of a violation can make a violation go away—that whenever a disparity can be proven to be small, it can be considered no disparity at all. So, if a racial disparity burdens only a small number of minority voters in a small, rural polling place, does the relatively "small" size of the harm argue against a finding of a Section 2 violation of law? Apparently so.

As Harvard Law School's Nicholas Stephanopoulos has observed, Alito ignores the words of the statute in adding these considerations of size. "Section 2 states that it applies to any 'denial or abridgment' of the right to vote. The court qualified that broad language, effectively inserting the word 'substantial' before 'abridgment,' with no basis in the text."5Nicholas Stephanopoulos, "The Supreme Court Showcased its 'Textualist' Double Standard on Voting Rights," Washington Post, July 1, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/01/supreme-court-alito-voting-rights-act/.

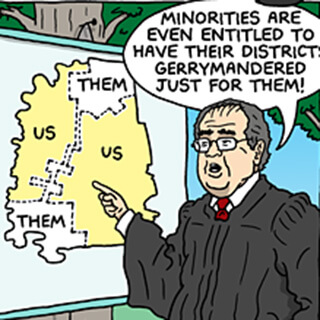

The third consideration on Alito's list is "the degree to which a voting rule departs from what was standard practice" in 1982. This is an additional factor that can be used more often by state and local governments defending a voting rule than by minority groups challenging it. Stephanopoulos refers to this standard as "the court's most astonishing extra-textual move" since "Section 2's whole point is to unsettle the status quo, to end voting restrictions that disproportionately harm minority citizens. The provision aspires to move American democracy forward, not keep it fixed forever in 1982."6Nicholas Stephanopoulos, "The Supreme Court Showcased its 'Textualist' Double Standard on Voting Rights," Washington Post, July 1, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/01/supreme-court-alito-voting-rights-act/.

Perhaps nothing exposes the rearward nature of this trumped-up guidepost more clearly than imagining it as a mandated consideration in 1965 when Section 2 was originally adopted. It would have allowed state and local governments to use their existing misdeeds as a defense against legal challenges. In 1965, twenty-one states required English-only literacy tests to qualify to vote. Most states permitted absentee voting by requiring proof of disability or a complete absence from the community and by requiring a notarized application submitted only at the county courthouse.7Report of the President's Commission on Registration and Voting, Washington, DC, 1963, 13–14, 65. Most states had few polling places in minority and poor communities. Most southern states had voting rolls with more dead white people than living Black people. In several states polling officials were all white, and ballots were numbered in such a way as to permit white officials to know how Black voters cast their ballots.8Hearings before the Subcommittee Number 5 of the Judiciary Committee, House of Representatives, Eighty-ninth Congress, on H.R. 6400, March 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 30, 31, and April 1, 1965; "Tan Voters Underwent Hardships: Many Waited In Lines for Hours; Some Didn't Wait," New Journal and Guide, May 14, 1966, 9; Francis X. Walter, "The May 3rd Primary In Alabama," Selma Inter-Religious Project Newsletter, May 16, 1966.

These common practices would have been used as a defense against any legal challenge under the Voting Rights Act, had Alito's guideposts been decreed as law in 1965. It would have been outrageous and unacceptable then. It is no more reasonable or acceptable now.

Alito's two remaining guideposts also make it more difficult to prove voting discrimination. Considering "opportunities provided by a State's entire system of voting" could be legitimate, if by "taking into account the other available means" includes requiring proof that those means are more accessible to the protected group and in fact fully compensate for some related disparity in access to voting. But, in upholding Arizona's law voiding all ballots cast in the wrong precinct, Alito made no such analysis. Therefore, it is highly doubtful any lower court will do so.

Finally, a consideration of the "strength of the State's interests" in a law or practice can be legitimate in voting cases, but Justice Alito chose among the many possible valid state interests to spotlight one in particular—election fraud, the single most misused and unproven rationale in current partisan voting disputes. "Fraud can affect the outcome of a close election, and fraudulent votes dilute the right of citizens to cast ballots that carry appropriate weight," Alito writes. "Fraud can also undermine public confidence in the fairness of elections and the perceived legitimacy of the announced outcome."

All true statements, in theory. But singling out fraud as the best example of a valid state interest when there have been no findings of widespread fraud across the states is worse than disingenuous. In the context of the close 2020 presidential elections in Arizona and Georgia, Alito's words signal that unsubstantiated charges of "fraud" are now available in voting rights cases as a strong "state interest." In effect, he is almost inviting the use of "fraud" on the same unproven terms as lawyers and government officials have used them in attempting to reelect Donald Trump by trying to discredit and disqualify votes on those terms primarily in majority-Black and -Brown counties.

In stirring, memorable words, Justice Elena Kagan dissented from the Court's majority opinion on behalf of its two other liberal members. "If a single statute represents the best of America, it is the Voting Rights Act. It marries two great ideals: democracy and racial equality," she writes.9Regrettably, in referring to the origins of the Voting Rights Act, Justice Kegan's dissent suggests she knows law better than history. She mentions "a march from Selma to Birmingham." It was in fact the Selma to Montgomery march that made voting rights history. But, eight years ago, the Court on which Kagan now sits voided Section 5 of the Act by ignoring the fact that Congress published thousands of pages of testimony, data, and information providing evidence of the substantial, new voting rights problems covered by Section 5 that people of color face in the states.10Steve Suitts, "States' Rights Resurgent: The Attack on the Voting Rights Act," Southern Spaces, August 29, 2013, https://southernspaces.org/2013/states-rights-resurgent-attack-voting-rights-act. As a result, by voiding Section 5 and now greatly weakening Section 2, the Court has left very little of the protections that Congress enacted and reenacted to advance voting rights.

A historic accomplishment, the Voting Rights Act has advanced democracy and racial justice. In 1992, voting rights attorney Laughlin McDonald wrote that the "amendment of section 2 . . . represented a strong congressional and judicial commitment to equality in voting."11Laughlin McDonald, "The 1982 Amendments of Section 2 and Minority Representation," in Controversies in Minority Voting, ed. Bernard Grofman and Chandler Davidson (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1992), 70. Also see Drew Days, "How the Voting Rights Act is the Most Effective Act on the Books," Southern Changes 4, no. 1 (1981): 16, 25–27, http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc04-1_1204/sc04-1_004/. But in recent years a majority of Supreme Court justices have abandoned their own self-professed adherence to the text of Congressional legislation in order to reach a result they prefer: voting laws that make it more difficult to prove racial discrimination and to block voter suppression. If the American people fail to rally and elect a Congress that will right the current Court's wrongs through passage of new legislation, the nation will be left without a safekeeping of either democracy or racial justice.

About the Author

An adjunct with Emory University's Institute for the Liberal Arts, Steve Suitts is the author of Hugo Black of Alabama: How His Roots and Early Career Shaped the Great Champion of the Constitution (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2017). Earlier in his career, Suitts served as the executive director of the Southern Regional Council, vice president of the Southern Education Foundation, and executive producer and writer of "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," a thirteen-hour public radio series that received a Peabody Award for its history of the civil rights movement in five Deep South cities.

Recommended Resources

Text

Anderson, Carol. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Davidson, Chandler, ed. Minority Vote Dilution. Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1989.

Davidson, Chandler, and Bernard Grofman, eds. Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965–1990. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Grofman, Bernard, and Chandler Davidson. Controversies in Minority Voting: The Voting Rights Act in Perspective. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1992.

Katz, Ellen, Margaret Aisenbrey, Anna Baldwin, Emma Cheuse, and Anna Weisbrodt. Documenting Discrimination in Voting: Judicial Findings Under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act Since 1982. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Law School, 2005.

Platt, Matthew B. "An Examination of Black Representation and the Legacy of the Voting Rights Act." Phylon 52, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 87–107.

Valelly, Richard, ed. The Voting Rights Act: Securing the Ballot. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2006.

Web

Days, Drew. "How the Voting Rights Act is the Most Effective Act on the Books." Southern Changes 4, no. 1 (1981): 16, 25–27. http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc04-1_1204/sc04-1_004/.

Jordan, Vernon E., and Lane Kirkland. "Section 5 and Voting Changes: The Heart of the Act." Southern Changes 4, no. 1 (1981): 36–37. http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc04-1_1204/sc04-1_006/.

McDonald, Laughlin. "The Attack on Voting Rights." Southern Changes 7, no. 5 (1985): 1–3. http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc07-5_1204/sc07-5_002/.

Willingham, Alex. "The Latest Attack on Voting Rights." Southern Changes 17, no. 3–4 (1995): 3–5, 13. http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc17-3-4_1204/sc17-3-4_003/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Voting Rights Act Extension, Report of the Committee on the Judiciary, Unites States Senate, on S. 1992, 97th Congress, May 25, 1982, 67. |

|---|---|

| 2. | The order in which Justice Alito listed his "guideposts" has been slightly altered here. I list his third item second for purposes of analysis. |

| 3. | See Hearings before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Judiciary Committee, House of Representatives, on H.R. 1407, H.R. 1731, H.R. 2942, H.R. 3112, H.R. 3198, H.R. 3473, and H.R. 3948, 97th Congress, May 6, 7, 13, 19, 20, 27, 28; and June 3, 1981; Report of the Subcommittee on the Constitution of the Judiciary Committee, United States Senate, 97th Congress, on S. 1992, April 1982. |

| 4. | The legislative history does make it plain that the "result" test has limits. It does not guarantee a right to proportional representation. |

| 5. | Nicholas Stephanopoulos, "The Supreme Court Showcased its 'Textualist' Double Standard on Voting Rights," Washington Post, July 1, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/01/supreme-court-alito-voting-rights-act/. |

| 6. | Nicholas Stephanopoulos, "The Supreme Court Showcased its 'Textualist' Double Standard on Voting Rights," Washington Post, July 1, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/01/supreme-court-alito-voting-rights-act/. |

| 7. | Report of the President's Commission on Registration and Voting, Washington, DC, 1963, 13–14, 65. |

| 8. | Hearings before the Subcommittee Number 5 of the Judiciary Committee, House of Representatives, Eighty-ninth Congress, on H.R. 6400, March 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 30, 31, and April 1, 1965; "Tan Voters Underwent Hardships: Many Waited In Lines for Hours; Some Didn't Wait," New Journal and Guide, May 14, 1966, 9; Francis X. Walter, "The May 3rd Primary In Alabama," Selma Inter-Religious Project Newsletter, May 16, 1966. |

| 9. | Regrettably, in referring to the origins of the Voting Rights Act, Justice Kegan's dissent suggests she knows law better than history. She mentions "a march from Selma to Birmingham." It was in fact the Selma to Montgomery march that made voting rights history. |

| 10. | Steve Suitts, "States' Rights Resurgent: The Attack on the Voting Rights Act," Southern Spaces, August 29, 2013, https://southernspaces.org/2013/states-rights-resurgent-attack-voting-rights-act. |

| 11. | Laughlin McDonald, "The 1982 Amendments of Section 2 and Minority Representation," in Controversies in Minority Voting, ed. Bernard Grofman and Chandler Davidson (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1992), 70. Also see Drew Days, "How the Voting Rights Act is the Most Effective Act on the Books," Southern Changes 4, no. 1 (1981): 16, 25–27, http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc04-1_1204/sc04-1_004/. |