Overview

The US Supreme Court is slowly but surely overturning Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed state support for unequal, segregated public schools. Citing religious freedom, Chief Justice John Roberts recently led the Court to sanction religious discrimination in publicly financed private schools. The decision further dismembers the nation's commitment to achieving equitable, effective public education for all.

Blog post

In a case decided on the grounds of religious freedom, the US Supreme Court took another big step on June 30 in supporting religious discrimination in publicly financed schooling and, more broadly, in overturning Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 landmark opinion that promised the end of racial segregation in public education.

The Court ruled in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue that the US Constitution’s guarantee of religious freedom prohibits a state from excluding religious schools when it finances attendance in private schools. There should be no misunderstanding about what this case means in regard to religion: states are now free to finance private schools that discriminate against students on the basis of students’ religions.

As troubling as that holding is, the opinion also constitutes a major, often ignored long-term impact on school desegregation. Today most students attending private schools are in religious schools, and most religious schools are effectively segregated and exclusionary by race. For this reason, Espinoza constitutes a regrettable, and significant, decision in the Supreme Court’s long and certain movement over the last forty years to overturn the Brown decision.

In the short run, the Court’s decision adds momentum to the school choice movement that has been lobbying in Washington and the state capitols to increase public funding of private schools through programs that often safeguard the private schools’ discretion to choose whomever they wish to admit as students. Already twenty-six of the fifty states have yielded to school choice advocates by enacting a variety of voucher programs financed by state appropriations and state tax credits.

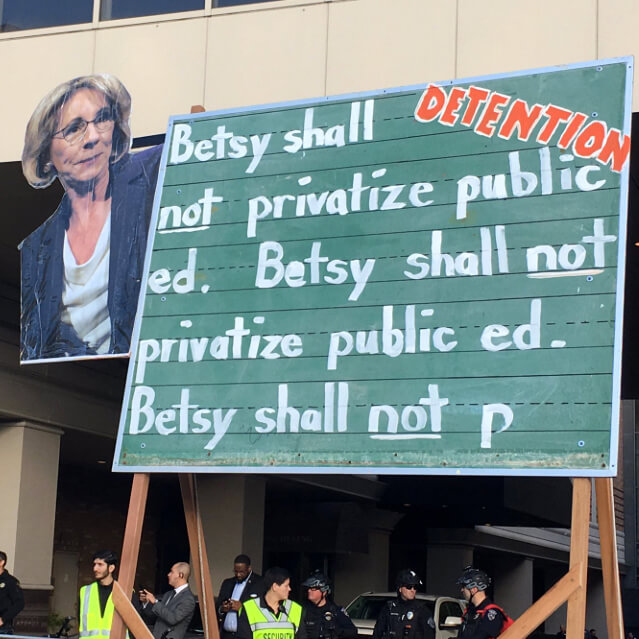

Together these voucher programs are diverting more than $2.1 billion annually to private schools. That sum is larger than the annual state funding of public schools in thirteen of the nation’s fifty states. And in January, decrying “failing government schools,” President Trump renewed his support for US Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’s plan to spend billions of federal dollars on private school vouchers.

Advocates of “school choice” claim they are advancing religious freedom, social justice, and civil rights when in fact, as I document in “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern ‘School Choice’ Movement," they echo the language and tactics used by southern segregationists in their efforts to evade school desegregation after Brown. It is there—in the history of the segregationists’ fight against Brown and in how the federal courts addressed their strategies—that the long-range impact of Espinoza becomes evident.

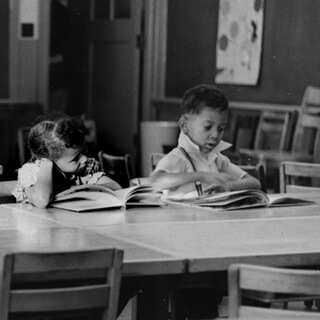

In the years following Brown, southern states passed dozens of bills to condemn and frustrate school desegregation. The overall strategy of massive resistance was based on two basic tactics. One was placing pupils in public schools according to what the segregationists claimed were children’s “ability to learn”—which they believed, but after Brown carefully avoiding saying, was inherently different due to race. The other was funding vouchers for private academies where segregationists were free to set up exclusionary admission standards.

By the end of the 1960s, the Supreme Court and other federal courts had effectively confronted this two-pronged strategy by ruling that most of the pupil placement laws for public schools were racially discriminatory in their application and that the South’s voucher programs were a violation of the US Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of “equal protection of the laws.” By that time, however, local and state funding had enabled the rapid growth of private schools—schools that were segregated, often with a token number of Black students to deflect federal scrutiny, and that increasingly professed nonracial reasons for their practices, often citing religion.

Many headmasters of the “segregation academies” by the early 1970s claimed their schools were motivated by religion. “Our people—supporters of the Independent schools—are convinced God is behind us,” asserted the head of the Louisiana segregated private schools. “People believe wholeheartedly that God doesn’t want us to mix.”1Steve Suitts, Overturning Brown: The Segregationist Legacy of the Modern School Choice Movement (Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020), 71. Whatever their purported nonracial rationale, the vast majority of the South’s private schools had become religion-based and remained nearly entirely segregated.2Ironically, the Court’s decision in Espinoza removes one of the few restrictions that the Southern segregationists’ voucher programs in the 1960s actually upheld—a prohibition against financing vouchers for students in religious private schools.

In retrospect, the 1970s also was the era signaling how and when the Supreme Court would turn away from its vigilant efforts over the previous two decades to implement the promise of Brown. The Court began issuing decisions that would block desegregation efforts in public schools—where most students of color seek a better education—and enable public financing of private schools that preserve virtually segregated, exclusionary education for white students.

As early as 1973, Justice William Rehnquist became the first member of the Court to issue a dissent from a school desegregation case relying on the precedent of Brown. In a case concerning school segregation in Denver, he condemned the Court’s opinion for requiring a school district to advance desegregation—employing the old scare word, “racial mixing”—where there were “neutrally drawn boundary lines” that sustained segregation.3Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 US 189 (1973), 258. See Justin Driver, The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind (New York: Pantheon Books, 2018), 278–283. As Driver notes, Justice Rehnquist as a Supreme Court law clerk had argued while Brown was being considered that the Court should not overrule Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), which had sanctioned state-sponsored segregation and the South’s Jim Crowism for three generations. Chief Justice Roberts was a law clerk to Justice Rehnquist in 1980.

With the ascendency of Justice Rehnquist as Chief Justice and the appointment of other justices across more than three decades, the Court increasingly refused to require public school districts to use effective methods of dismantling school segregation. In 2007, the Court turned Brown on its head when Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that Brown commanded school districts to avoid using race as a consideration, even for the purpose of recognizing and diminishing public school segregation. “When it comes to using race to assign children to schools,” Roberts wrote without doubt or irony, “history will be heard.”4Parents Inv. In Community Schools v. Seattle School, 127 S. Ct. 2738 (2007). In truth, the Court silenced the historical voices and promise of Brown.

The Supreme Court’s strategy in addressing the second prong of the old segregationists’ strategies—banning government financing of segregated private schools—had a robust but short-lived revival in the early 1980s. Chief Justice Warren Burger used majestic language in 1983, holding that a religious school, Bob Jones University, could not require segregation on its campus and retain an IRS tax exemption. “The Government has a fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education—discrimination that prevailed, with official approval, for the first 165 years of this Nation’s constitutional history,” he wrote. “That governmental interest substantially outweighs whatever burden denial of tax benefits places on petitioners’ exercise of their religious beliefs.”5Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983).

But barely a year after the Bob Jones decision, the Supreme Court slammed shut the courthouse door on those seeking to challenge the IRS’s weak enforcement of that decision and other violations among private schools. Parents of twenty-five Black public school children sued the IRS, charging that its standards and procedures were inadequate to fulfill its obligation to deny tax-exempt status to racially discriminatory private schools. In 1984, the US Supreme Court held that the parents had no standing to bring such a suit.6Allen v. Wright, 468 US 737 (1984).

In more recent years, Justice Anthony Kennedy led the Court in nailing that door completely closed and unleashing private schools from constitutional restraints on receiving taxpayer funds. Arizona’s program of tax credit vouchers allowed individuals and corporations to give tax dollars to private schools instead of paying them to the state. The program was similar to the Montana program in Espinoza and to the private school funding programs that the Supreme Court had outlawed in prior cases in the 1960s, including in Prince Edward County, Virginia, where Justice Hugo Black struck down both direct and tax credit-based vouchers.7Griffin v. School Bd. of Prince Edward Cty, 377 US 218 (1964).

In 2011, Justice Kennedy held for the majority that tax credit vouchers did not involve public funds or any state action that the Bill of Rights would prohibit. “While the State, at the outset, affords the opportunity to create and contribute,” Kennedy wrote, “the tax credit system is implemented by private action and with no state intervention,” with the result that citizens had no standing to challenge the constitutionality of the tax credit voucher program.8Arizona Christian School Tuition Org. v. Winn, 131 S. Ct. 1436 (2011), 1448. Justice Kennedy’s opinion considered whether the First Amendment’s clause requiring separation of church and state, by way of application to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, prohibited providing state tax credit vouchers to religious schools.

The Court’s opinion in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue holds that there is state action involving constitutional principles that citizens can enforce when they challenge a state exclusion of religious schools from its program of tax credit funding on the basis of religious freedom. However, according to the earlier Arizona ruling, there is no state action when citizens challenge a program of tax credit funding of religious schools on the basis of separation of church and state. It is an odd double standard that makes no sense and represents result-directed law.

Worse, Espinoza moves the Court one step closer to overturning Brown. With Espinoza, state programs can now finance private schools that discriminate on the basis of religion, which has become over the decades a frequent proxy for race. It sanctions expanding state programs that permit private schools across the nation to maintain what strategic southern segregationists sought to achieve after Brown—virtual segregation and exclusion of children of color—while its prior rulings have insured that public school districts cannot recognize race to voluntarily employ effective strategies to desegregate its own schools.

Long gone is the nation’s “fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education.”

About the Author

An adjunct with Emory University's Institute for the Liberal Arts, Steve Suitts is the author of Hugo Black of Alabama: How His Roots and Early Career Shaped the Great Champion of the Constitution. Earlier in his career, Suitts served as the executive director of the Southern Regional Council, vice president of the Southern Education Foundation, and executive producer and writer of "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," a thirteen-hour public radio series that received a Peabody Award for its history of the civil rights movement in five Deep South cities.

Cover Image Attribution:

A mural by Michael Young celebrating the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Supreme Court decision, in the Kansas State Capitol, Topeka, Kansas, May 23, 2019. Photograph by Flickr user Joe Shlabotnik. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Recommended Resources

Text

Carl, Jim. Freedom of Choice: Vouchers in American Education. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2011.

Carpenter II, Dick M., and Krista Kafer. "A History of Private School Choice." Peabody Journal of Education 87, no. 3 (2012): 336–350.

Driver, Justin. The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind. New York: Pantheon Books, 2018.

Rooks, Noliwe. Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education. New York: The New Press, 2020.

Web

Erwin, Benjamin. "Interactive Guide to School Choice Laws." National Conference of State Legislatures. April 18, 2019. http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/interactive-guide-to-school-choice.aspx#/.

Green, Erica L. "Religious School Choice Case May Yield Landmark Supreme Court Decision." The New York Times, January 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/21/us/politics/supreme-court-religion-school-vouchers.html.

Reardon, Sean F., and John T. Yun. Private School Racial Enrollments and Segregation. Cambridge, MA: Civil Rights Project, June 26, 2002. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/private-school-racial-enrollments-and-segregation/Private_Schools.pdf.

Totenberg, Nina and Brian Naylor. "Supreme Court: Montana Can't Exclude Religious Schools from Scholarship Program." NPR, June 30, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/30/883074890/supreme-court-montana-cant-exclude-religious-schools-from-scholarship-program.

U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. "Private School Enrollment." Updated May 2020. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgc.asp.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Steve Suitts, Overturning Brown: The Segregationist Legacy of the Modern School Choice Movement (Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020), 71. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Ironically, the Court’s decision in Espinoza removes one of the few restrictions that the Southern segregationists’ voucher programs in the 1960s actually upheld—a prohibition against financing vouchers for students in religious private schools. |

| 3. | Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 US 189 (1973), 258. See Justin Driver, The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind (New York: Pantheon Books, 2018), 278–283. As Driver notes, Justice Rehnquist as a Supreme Court law clerk had argued while Brown was being considered that the Court should not overrule Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), which had sanctioned state-sponsored segregation and the South’s Jim Crowism for three generations. Chief Justice Roberts was a law clerk to Justice Rehnquist in 1980. |

| 4. | Parents Inv. In Community Schools v. Seattle School, 127 S. Ct. 2738 (2007). |

| 5. | Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983). |

| 6. | Allen v. Wright, 468 US 737 (1984). |

| 7. | Griffin v. School Bd. of Prince Edward Cty, 377 US 218 (1964). |

| 8. | Arizona Christian School Tuition Org. v. Winn, 131 S. Ct. 1436 (2011), 1448. Justice Kennedy’s opinion considered whether the First Amendment’s clause requiring separation of church and state, by way of application to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, prohibited providing state tax credit vouchers to religious schools. |