Overview

Ruthie Yow draws on her oral history work with Virginia Ward, the first black student at Pebblebrook High School in Cobb County, Georgia, to examine class dynamics in the history of desegregation.

Introduction

|

| Virginia Ward's yearbook photo, Pebblebrook High School, 1970. |

Virginia Ward is not a small woman, but the fineness of her hands and the way her gray curls sweep around her ears make her seem so. She is missing her left front tooth and when she laughs, she leans backward and then forward again, as if in a rocking chair. She grew up in Mableton in Cobb County, Georgia, "over 'cross the [Chattahoochee] River" from Atlanta. In the fall of 1966, Ward desegregated Pebblebrook High School. In the first few frightening days, she remained sure other black students would arrive, but the months passed and "no one came."1Interview with Virginia Ward, March 13, 2009. All quotations from Virginia Ward that follow are drawn from this interview, and will not be further noted. Ward endured two years as Pebblebrook's only black student. She was not written up in the local paper, nor feted by her community for her accomplishments. When she graduated in 1970, her friends and congregation were amazed: "Virginia," she remembers them saying after they watched her assemble in cap and gown with her white classmates, "you really was the only one!"

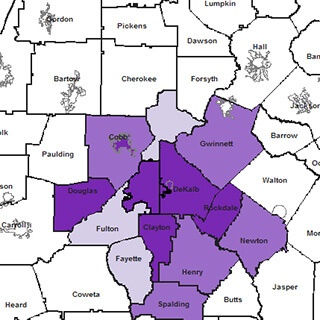

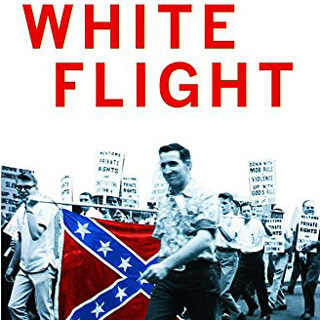

This story is about Virginia Ward's courageous desegregation of her local high school, but it is also about the implications of neglecting class and poverty in histories of school desegregation. The role of poverty in Ward's account acts as a reminder of the struggles of black integrators who were not upper-middle class or the chosen children of their communities, students who experienced their class as equally marginalizing as their race. As legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw suggests, socially constructed categories, i.e. "black" and "white," will always be with us; the problem is rather that "the descriptive content of those categories and the narratives on which they are based have privileged some experiences and excluded others."2Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence against Women of Color," in Critical Race Theory: Key Writings that Formed the Movement (New York: The New Press, 1995), 376. Crenshaw describes the importance of "intersectionality" to the experiences of black women, specifically, but her insights can be applied to class and race in narratives of school desegregation: when identity is configured "as an either/or proposition . . . the identity of a poor person [of color is relegated] to a location that resists telling." In many narratives of school desegregation, "poor black student" is a "position that resists telling;" in contrast, there has been careful attention to the class position of whites who resisted desegregation.3The class politics of white resistance have received thorough treatment in recent scholarship on desegregation. In her history of desegregation in New Orleans, Liva Baker describes the white mothers, called the "cheerleaders," as carrying signs that read "If your [sic] poor, mix. If your [sic] rich, forget it. Some law!" The first ward to desegregate was the "politically powerless, materially disadvantaged Ninth Ward." Liva Baker, Second Battle of New Orleans: The Hundred Year Struggle to Integrate the Schools (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 398. Similarly, in Atlanta, lower-income white parents protested that because they could not move away or choose private education like the "silk stocking crowd," they would be disproportionately affected by desegregation. Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 139. In Charlotte, the CPA (Concerned Parents Association) was composed of "well-heeled whites;" these "upwardly mobile parents" mobilized to prevent their children from being bused away from their well-resourced neighborhood schools. Matthew Lassister, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics on the Sunbelt South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 139-140. Because there are, likely, thousands of "first children" yet to be heard,4When Brown was decided there were 4,000 segregated school districts in the south; three years later 712 of them were desegregating, sending 300,000 black students to integrate schools. This suggests that the numbers of "first children" across the South, who integrated schools alone or in small cohorts, is in the thousands. Robert L Hayman and Leland Ware, eds, Choosing Equality: Essays and Narratives on the Desegregation Experience (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009), 4. Ward's story is only one among many that deserve a hearing, but it is also true that Ward's "difference made a difference" that is not often acknowledged in the public memory of desegregation.5Crenshaw, 376.

Pre-Brown

|

| Map showing the location of Mableton, Georgia, 2012. |

Virginia Ward's people were "Indians from Black Hawk Hill," and they had owned property in Mableton for many years. Ward, the third youngest of fourteen, was raised on her father's land. Her mother worked at the Wailea Cotton Mill and her father sold his homegrown produce and picked up odd jobs. "We had to be," she said laughing, "the poorest peoples in the world." But there was always milk and butter from the cow and eggs from the hens, and the bounty of a garden "just about as big as some people's homes." Fourteen children was a formidable labor force, and her father would brook no laziness. She recalled having a harder row to hoe, quite literally, than her friends: "We were taught . . . to work work work. . . . My daddy didn't believe in welfare." Although the demands at home were significant, Ward's parents insisted that she and her siblings earn their high school diplomas. She began at Washington Street Elementary, which all her friends attended. She remembered: "We all had to go to Washington Street. We had one bus driver—Lucius. He picked up everybody in Mableton and Austell. Cause we all went to one school. That's how we got to know all the blacks that's in Mableton cause all of us had to ride the same bus."

Ward's memory of Lucius and the single school bus speaks to the nostalgia that is often intertwined with desegregation for students and parents of the pre-Brown era.6"Brown era" refers to the years bookended by Brown I in 1954 and Milliken v Bradley in 1974, the case that prohibited the use of cross-district busing in instances of de facto segregation and marked the turn away from the dramatic (and largely effective) desegregation remedies of the previous decade. Among the many legacies of Brown is the loss of black schools and their black leadership to the integration of existing white institutions which were reputedly better staffed and resourced. But some black community members, teachers and students remember that the interdependence and familial care fostered by these all-black institutions was, for them, far more valuable than the ineffable "good" of integrated schools. In her home community in Mableton, Ward's difference didn't register so starkly, her background was not isolating; her teachers knew her and her abilities. The sacrifices of students like Ward and the loss of all-black institutions are a critical part of understanding the contemporary politics of desegregation in black communities. As scholars such as Barbara Shircliffe have shown, black communities have undertaken their own reconstructions of desegregation history—in some cases quite literally.7Barbara Shircliffe, The Best of that World: Historically Black High Schools and the Crisis of Desegregation in a Southern Metropolis (New York: Hampton Press, 2006). Shircliffe describes a Tampa, Florida, community that successfully petitioned for a new high school named after the local all-black school that desegregation had "taken." The restoring of their cherished school was a victory especially for the students who had been bused unwillingly to integrating white schools in the Tampa area. The new "old" high school stood not for segregation or its attendant evils but for a resistance to the erasure of the past and the resilience of community.

"Break[ing] That School In"

Virginia began high school at South Cobb High, a formerly all-white high school which was already desegregating.8Until the county schools began to desegregate, black students had only one high school to attend, Lemon Street High, in downtown Marietta, the county seat. Cobb County adopted "Freedom of Choice" in 1965, but the county's high schools did not desegregate all at once. South Cobb High, for example, began provisionally desegregating before Pebblebrook High School, and as it was in neighboring Austell, Virginia spent her ninth grade year there before transferring to Pebblebrook, her district school. In her ninth-grade year, there were "four or five other blacks," as she remembered, attending South Cobb. But in 1966, Virginia enrolled at Pebblebrook High School, officially her district high school, which had not yet begun to desegregate. She imagined a similar ratio of white to black students as at South Cobb—not a happy thought, but a vaguely comforting one. "But when I got to Pebblebrook," she remembered, "I was like, okay, maybe the first day, no blacks, second day, no blacks." The days and weeks passed and "no one came." When it became clear she would be the sole black student for the remainder of that year, she resisted the urge to request that her parents transfer her because "it was mandatory. I had to go." Virginia's belief that she "had to go"—she could have legally gained admission elsewhere in the county—is suggestive of her parents' expectations and demands and perhaps, too, her own sense of duty. ("Someone had to do it!" she said later.) When Ward began her senior year at Pebblebrook, she was finally joined by another black student from her community, a girl who entered the eleventh grade.

Of the people at Pebblebrook, Ward offered with equanimity that "some were good" and "some were bad." She knew, whether by their actions or her own intuition, who was who. She remembered of one teacher, "I knew he was prejudiced . . . I heard him call me 'nigger.'" The evening of the day Virginia overheard the slur, her family gathered for dinner and her father asked her about school. "He was not a talker," she says with a smile, "but he was a good listener." Virginia told him and her siblings what her teacher had called her. She waited for her father's response—some word of wisdom or warning—but none came. The next day, however, he took her to school and left her in the lobby while he had a brief visit with the principal. Later that morning a fellow student taunted, "We're having a meeting because of you." The principal had called an all-school assembly to address the incident. Virginia remembered that he opened the "meeting" by asking her to stand. She recalled his words as she stood up alone in an otherwise quiet auditorium: "If anybody got a problem with integration, it's here. And Virginia is here. And no one is to make her uncomfortable. And if Virginia has a problem she can come to me." It was "so embarrassing" she remembered, her good-natured laughter softening the hard edge of the memory.

|

| Virginia Ward, center, in a Future Business Leaders of America yearbook photo, Pebblebrook High, 1970. |

The scene she described must have been one of deeply-felt ambivalence: the principal's requesting that Virginia stand up (as if students did not know or recognize her sole black face among them) was extending an olive leaf with one hand and stoking the fire with the other. By being turned into a spectacle, and the embodiment of integration—"it's here now"—Virginia experienced the antagonisms and antinomies of her daily life writ large. Perhaps the principal had meant to protect Virginia with his gesture. Yet any seasoned principal or teacher ought to know that an edict from an authority figure invites abuse, not sympathy, from fellow students. Virginia's profoundest challenges from her peers came after the principal's injunction. Virginia's father's words to her at the beginning of the school year were prescient: "You're gonna have to break that school in."

Scripture

"Every day," Ward remembered, "he'd sit behind me in class. Every day he call me nigger. Every day, every day." She was recalling the student who dedicated himself to taunting her—quietly and doggedly, repeating his incantation every time the two took their seats. She told her pastor and mentor, Reverend Aaron, who assured her that one can "change people with the Word." So for the weekly essay assignment in that class, Ward began selecting and writing about passages of scripture. She quoted her own determination: "I [will] find a scripture for that one boy who calls me a nigger, every day, every day. I will find one just for him." She laughed while claiming she had summoned "the worst peoples in the Bible" to her cause and read their exploits and cruelties aloud to her class—directing her pseudo-sermons toward the boy in the chair behind hers. After several Mondays, Ward's strategy and weaponry prevailed. Without any kind of disciplinary intervention from teacher or principal, the offender stopped his name-calling. Since her arrival, she said, "every day, all I heard is ‘nigger, nigger nigger.' It was a song for them." But her triumph in the classroom spread, and "after a while," she remembered, "you didn't hear it . . . walking down the hall." Her peers were wary of her, muttering, as she approached, "There she come again, with the scripture, there she come."

Ward wove this story in and out of her narrative, referring back to the transformative power of her scripture essays and her pastor's assurances that "when they hear it, they'll know." Although she was without the resources or support to broadcast her battles and victories, and although she was a struggling student, neither popular nor high-achieving, she powerfully fashioned herself as a teacher of her peers. This role and her pedagogy reappear in later anecdotes about her relationships as an adult, when once again she challenged the racism and classism around her, and the narrowness of the known story.

At the Margins

When asked if she was ever scared during her years at Pebblebrook—of the bathroom or the locker rooms, the dangerous fiefdoms of adolescent girls—she countered that she was "not afraid of people." She offered that because her family was so poor, it was often the feeling of "not having anything" that isolated her. "It looked like the whole world rich," she recalled without rancor. "And going to the white school—you know you are really poor." She affectionately described a woman she called her "school mom." Mrs. Groover, the mother of a classmate who did not know of his mother's kindness to Ward, volunteered to take her to the dentist and doctor, for which her own mother had neither money nor time. "She was the first one who took me to get a hamburger," Ward remembered—a special treat because what could be gotten at home was never extravagantly purchased elsewhere. Mrs. Groover's unsolicited, and in a certain sense anonymous, generosity both mitigated and heightened the particularity of Ward's poverty at Pebblebrook. Yet it was not only being poor and adjusting to a wealthier, white "culture, clothing and language," but also being "slow," as Ward calls herself, that defined the character of her time there.

|

| Virginia Ward, back row right, in a Library Club yearbook photo, Pebblebrook High, 1970. Cynthia Beavers, who began at Pebblebrook in 1969, stands next to Ward. |

Perhaps "slow," in Ward's parlance, was in fact dyslexia, or in education expert Ann Smith's terms, "a deficit in [her] education" in elementary and middle school.9Interview with Ann Smith by the author, March 10, 2009. Whatever the case, Ward asserted that being black at Pebblebrook had nothing on being "slow." As she said: "that was hard[er] than even just being black and going to school and being called nigger . . . . [And] it's hard going to school when [there are] no programs for slow students . . . . It was a struggle to be in a white school. It's a struggle where you look around and everybody's smart." In an era without tracking and before the maturation of special education programs, Ward attended classes with students who excelled with ease—or so it seemed to her. After weeks of difficulty with her assigned reading, she found a friend in the librarian who ordered her required reading in books-on-tape, and her grades improved dramatically. Determined to endure her final two years and walk away with a diploma, harder-earned than anyone could imagine, Ward remarked of those books on tape, "It was a new world."

When it came time for graduation, no fairy godmothers intervened to purchase a class ring or a visit to the beauty parlor. Ward called the dark hair which framed her young smiling face in her graduation photograph, "a mess." Although Ms. Groover and the school librarian smoothed her path the best they could, Ward locates herself at the margins, socioeconomically, academically, and culturally. She related with some indignation that the members of her church who came to her graduation in 1970 were amazed to see her marching in the all-white procession. That her two years alone at Pebblebrook had gone unnoticed suggests that Ward's position outside the traditional desegregation narratives—her class, her academic troubles and her separation from her black peers—obscured her courageous struggle. Ward's story, in which being poor and being black inextricably reinforce her marginality, points to the way in which the "dream" of desegregation, especially in the South where the reality proceeded apace through the 1970s, would be foiled by other realities: white flight, evolving discourses of colorblindness and property rights, and structural poverty.10In 1980, as a result of desegregation, only 37% of black students attended mostly black schools, by the year 2000, that number had grown to 69%, quickly approaching the 1968 numbers for Southern black students. Robert L. Hayman and Leland Ware, eds, Choosing Equality: Essays and Narratives on the Desegregation Experience (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009), 319.

A Shared Past

Through Job Corps, Ward got work almost immediately with the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP. Although she was hired to be a "secretary," her supervisor encouraged her to become an organizer, to travel with other staff members and take on a greater role within the chapter. Ward liked the idea a great deal, but her mother "said no," and Ward knew—although her colleagues at the NAACP pressed hard for her to join them—that there would be no further negotiation. Instead, her mother encouraged Ward to leave the NAACP and apply for a job at the First National Bank (what would become Wachovia). She was hired as a maintenance person in the bank cafeteria. To this, her mother also "said no"—insisting that her daughter was better than that work and should say so. After a month, Ward summoned the courage to pursue a job in bookkeeping where her supervisors extracted hours of unpaid overtime and monitored her personal life and assessed her class status with questions about her mother's job and her friends from "the mill." After twenty-one years at the bank, Ward took Reverend Aaron's advice to start her own business painting and cleaning newly constructed homes and apartments. Although she possessed no relevant skills or capital, Ward set off, undaunted, toward entrepreneurship.

Of that time, Ward testified that she learned "how to hold to business and how to work with people," how to win bids and demand fair pay, how to do a job so well that the customer requests you again. When Ward says, as she did many times, "life is a struggle," she means not that certain incidents were challenging, but rather that its arc is defined by struggle—getting very little, and always expecting even less. Despite her own "illiteracy" and her clients' "prejudice," Virginia ran a business—sometimes two—which supported her and her four adopted children. School, she believes, doesn't ready students for work; it is the world that does that—especially a world that exacts special penalties for "being black and a woman." Never, Ward intoned, "take a job for granted."

|

| Virginia Ward, in Pebblebrook High's BrookSpeak, 2009. |

As the sole breadwinner for her family of four children, Ward augmented the income from her cleaning business by taking old and infirm clients into her home for full-time care. Ward was a demanding and yet deeply loving mother figure to even the patients who reminded her of her Pebblebrook peers. Some years ago, a young man brought his elderly aunt to Ward with the warning, "she's kinda prejudiced." Virginia assured him knowingly, "we'll deal with it," adding, "I didn't go into my background." The client had been a school teacher in Nebraska and repeatedly assured Ward that "they better not've put one of y'all in my classroom," vowing, "I wouldn't even live in a neighborhood with you all." Ward remembered thinking, with some relish, "I had her all day . . . [she] was gon' learn from me." After a short while, the two had become the "best of friends," and Virginia often brought her client to church with her, seating her in the pews "with the children." With the children? I had asked, not understanding. "I always made sure she sat with the kids," so that the older woman would come to realize, after so many years, that "children are children . . . they all do the same things . . . they all have to be taught." In telling this, Ward still marveled that her friend and client "got old to learn that," but under Ward's instruction, learn she did.

This tale is poignant not only for the image of an old white woman displaced from her former life, values and environment and deposited in a pew with a handful of unruly black children, although that image conveys well the creativity of Ward's pedagogy. Rather, what gives this story its power is the notion of an open and still-viable channel that connects the schoolteacher's generation of racist white folks to Ward's generation of integrating black students and then, finally, to the generation of young pupils in her church's congregation. Ward's maxim is that no lesson can come too late, and that no one gets too old to learn. For Ward, this gentle prodding of people into the unknown is what makes change possible, even in a deeply unjust society, and is what makes the progress that integration promised real. Lingering, enduring possibility surges through Ward's narrative—and it is this sense of a "revolution," not lost but rather deferred, that helps to re-narrate school desegregation, and encourages her listeners to be as resourceful and open-hearted as Ward in broadening narratives of a shared past.

A Familiar Narrative

Right around the corner from Pebblebrook High, and a few years earlier, a more familiar desegregation narrative unfolded. Daphne Delk was the Virginia Ward of her local high school's desegregation process. Unlike Ward, Delk chose her fate consciously, petitioning her parents and the school board for the opportunity to attend Marietta High School, which even then she felt was her "destiny."11Interview with Daphne Delk by Jessica Drysdale and Jay Lutz, November 7, 2009, Kennesaw State University Oral History Project, Cobb NAACP/Civil Rights Series No. 7. A stellar student, Delk sought what she saw as the greater academic resources and challenges of the all-white high school, and she excelled there, going on to college at Fisk University and into the medical technology field. Though she too ate many lunches alone, Delk's success in making a place for herself was understood to demonstrate Marietta's more progressive racial climate; the spring she graduated, she was voted Girl of the Year by her classmates. Her father, who spent two years at Stanford on the GI bill and her mother, who worked for a prominent white family, were active in and dedicated to their community, and Delk's preparation and support network for her integration of Marietta High were substantial.

These outlines of Delk's biography and experiences are familiar to desegregation history, even if hers is not a household name. Virginia Ward's very different story demonstrates the wide breadth of desegregation experience. Understanding the connection between Ward's story and the implications of class for the legacy of desegregation requires a sense of what "middle class" and "poor" have meant in the decades since Brown. In the wake of the Civil Rights era's major victories, the black middle class of Ward's youth had begun to enjoy the material benefits of higher education and white collar jobs, as "class position began to affect mobility for blacks as it always had for whites."12Jennifer Hochschild, Facing Up to the American Dream: Race, Class and the Soul of the Nation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 44. Since the sixties, as Thomas Shapiro and others have demonstrated, the black middle class has grown substantially, and, as of the late 1990s, the number of black men in middle class jobs had grown dramatically, accompanied by the shrinking of the wage gap between black and white earners.13Thomas Shapiro, The Hidden Costs of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 6. Yet it's also true, and extensively documented, that due to de-industrialization, federal economic policy and entrenched residential segregation, the more fragile lower- middle class has become poorer as their upper-middle income peers prospered.14Pattillo-McCoy comments that since the 1970s examinations of the black "underclass" have constituted a "research industry" stoked in large part by William Julius Wilson's two seminal works on class and race,The Declining Significance of Race and The Truly Disadvantaged, the latter of which documented the plummeting employment opportunities for black Americans and the widening gap between poor black families and middle class black families. Mary Pattillo-McCoy, Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle Class (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 20. So while middle-class black students and their upwardly-mobile parents are crucial to the story of school desegregation, so too are the poor families whose wagons were not firmly hitched to the star of post-Civil Rights mobility.

Raising their children in that moment of promise and peril for poor and working class black Americans, Ward's mother and father saw a potentially white-collar future for their daughter. Even if she didn't get a college degree, they hoped her material comfort and income would exceed their own.15Pattillo-McCoy points out that obtaining a college degree is a "strict" standard for middle-class membership; a more widely applied rule is that a family earns "two times a poverty-level income," 15. Ward's story of desegregating Pebblebrook High and her life after graduation speak to the economic precariousness of being lower-middle-class and black, a theme that popular narratives of desegregation have seldom expressed. Public education had, in the past, played a crucial role in creating opportunities for structurally marginalized students, but the increasing racial isolation of poor children of color in high-poverty schools today means that children like Ward face even greater odds than she did. According to recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2009, only three percent of black public school students attended "low poverty" schools, and eighteen out of the nation's largest twenty districts were less than 50% white, a number that is sure to shrink, as desegregation scholar Gary Orfield has asserted, as Hispanic student populations increase over the next decade.16Gary Orfield and Chungmei Lee, "Historical Reversals, Accelerating Resegregation and the Need for New Integration Strategies," A Report of the Civil Rights Project, UCLA, August 2007. The NCES estimates the dropout rate for students of color (specifically black and Hispanic students) at almost 40 percent nationally; the same data shows that more than one third of black children live in poverty. Race matters, as Cornel West would say, but so does class, and a full picture of school desegregation today and forty years ago will show both at work in the lives of students and their families. Evelyn Higginbotham's theorization of race as a meta-language speaks to how class and color cannot be decoupled for black communities then or now. She writes that race must be recognized for "its powerful, all-encompassing effect on the construction and representation of other social and power relations, namely, gender, class, and sexuality."17Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, "African American Women's History and the Metalanguage of Race," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol.17, No. 2, Winter 1992, 252. Although Higginbotham's insight is powerfully true, in the case of desegregation history, the "all-encompassing effect" of race on class has at times obscured the important difference class made for desegregators like Daphne Delk. Middle class backgrounds meant toe-holds for inclusion that Ward and generations of low-income black students after her have not had.

Over the decades since Brown, historians have interpreted the desegregation process across the US South and North through a variety of lenses, but the impact of class and poverty in the lives of desegregators have gone, for the most part, unaddressed. Barbara Shircliffe and Vanessa Siddle Walker have described the nostalgia with which some black communities remember their segregated schools and the dynamic of a large, tight-knit family that these all-black institutions cultivated and sustained.18Barbara Shircliffe, The Best of That World: Historically Black Schools and the Crisis of Desegregation in a Southern Metropolis (Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2006) and Vanessa Siddle Walker, Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1996). R. Scott Baker and Richard Kluger, among others, have traced school desegregation efforts back to court cases of the 1930s and ‘40s, revealing that many courageous children and families preceded those of Little Rock or New Orleans.19R. Scott Baker, The Paradoxes of Desegregation: African American Struggles for Educational Equity in Charleston South Carolina, 1927-1972 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006) and Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board and Black America's Struggle for Equality (New York: Random House, 1975). The histories of these desegregation sagas and others—the Little Rock Nine, the children of New Orleans and the busing crisis in Boston—have been vividly told by Liva Baker, Karen Anderson and J. Anthony Lukas.20Liva Baker, The Second Battle of New Orleans: The Hundred Year Struggle to Integrate the Schools (New York: Harper Collins, 1996), Karen Anderson, Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2009), J. Anthony Lukas, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (New York: Knopf, 1985). Historians Pete Daniel and Elizabeth Jacoway have persuasively argued that the legacy of Little Rock's Central High is very much with us today, as its actors—black and white students—grapple with the mythology entwined around their adolescent actions.21Elizabeth Jacoway, Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis that Shocked the Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007), Pete Daniel, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2000). The fiftieth anniversary of the Brown decision saw a deluge of literature about the "failure" of Brown and its lost dream of education equity, and a bounty of work about what integration does and should mean now.22For example, Peter Irons, Jim Crow's Children: The Broken Promise of the Brown Decision& (London: Penguin, 2002); Charles T. Clotfelter, After Brown: The Rise and Retreat of School Desegregation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004). Jennifer Hochschild and Terry M. Moe, though at different ends of the political spectrum, both demonstrate the marginality of desegregation in the scholarship of education reform and educational equity. Although much of this work implicitly dismisses the importance of racially balanced schools and classrooms, researchers like Gary Orfield continue to crusade for the desegregation of increasingly homogenous urban and suburban schools. Clearly, the life of Brown is a much-examined one.

In the current era of school re-segregation, it is necessary to listen to the testimony of Brown's first children, to explore its rich diversity and to probe the silences in the known narratives. Without attention to the dimensions of class and structural poverty in desegregation history, the decision in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1—the landmark 2007 case which made student assignment on the basis of race unconstitutional—makes a kind of perverse sense. That is, if race is seen to be the only operative force in the lives of students and in their schools, then one might agree with the infamous declarations of Chief Justice John Roberts, "the way to stop discriminating on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race," and Justice Clarence Thomas, "[Today's school desegregation plans] appear to rest upon the idea that any school that is black is inferior, and that blacks cannot succeed without the benefit of the company of whites."23Roberts's words are drawn from the plurality opinion in Parents v Seattle in 2007. Thomas' comments date back to his concurring opinion in the 1995 case Missouri v Jenkins. The words of Roberts and Thomas reinforce the importance of investigating both race and class in desegregation's history and its contemporary politics, rather than allowing the terms and their context to shadow and obscure each other in public discourse and public memory. As Richard Kahlenberg states, it is not the "black schools" that are inferior, it is the poor schools—very often composed of students of color whose parents do not and historically have not had the choices available to middle- and high-income white parents.24Richard D. Kahlenberg, All Together Now: Creating Middle Class Schools Through Public Choice (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001). While the school desegregation plans of the Brown era emphasized race-based desegregation to dismantle de jure segregation, contemporary desegregation plans must combat middle- and upper-class white flight spurred by southern desegregation efforts of the late sixties and early seventies and the residential segregation that has always been a feature of northern places like Chicago, Detroit and New York. The contemporary conversation about public education prismatically refracts these historical and cultural forces, and searching the stories of desegregators reveals new slants of light.

|

| John T. Bledsoe, Rally at State Capitol, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1959. |

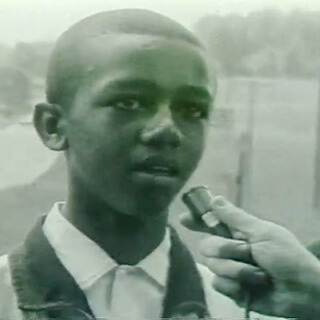

Perhaps the most widely familiar stories of desegregators are the personal memoirs of middle-class and upper-middle class integrators. These memoirs demand attention because they are an accepted shorthand: for generations of TV watchers and news listeners outside the perimeters of the crises, the internationally known story of the Little Rock Nine and the post-graduation fame of Charlayne Hunter-Gault have served as a means to understand how the injustice and abuse that desegregators suffered paid off in individual success and the advancement of "the black community." Allowing just a few chronicles to stand in for a rich spectrum of desegregation experiences produces a form of closure that precludes a nuanced conversation about the merits and shortcomings of historical desegregation.25Although the issue of re-segregation is a pressing one in both the South and the West and has historically been a persistent problem in the urban North, the context for this paper is the de jure school segregation of the South.

In the memoirs of Little Rock and in Hunter-Gault's biography, the authors make the trauma of desegregation coherent so as to present a trajectory that begins with violence and disorder but resolves in triumph—legal or personal and sometimes both. The memoirs obscure the role of class by spending little time describing the crucial groundwork for the students' success laid by their families' class and social connections, their parents' jobs, and their education backgrounds. The Little Rock Nine, especially, emblematize desegregation broadly in public memory, but although the Nine are clearly middle class students, public memory of them and their own shaping of that legacy does not contemplate the difference their middle-class-ness made. By contrast, a history of desegregation that can perhaps better inform present struggles for educational justice will incorporate a diversity of experiences and memories which acknowledges that class powerfully mediated the hardships faced by integrating students.

Three of the Little Rock Nine have written full-length memoirs: Melba Pattillo Beals' Warriors Don't Cry, Carlotta Walls LaNier's A Mighty Long Way and Terrence Roberts' Lessons from Little Rock chronicle the dramatic year (1957) of the integration of Central High. Beals' memoir, published first, has won the most attention and acclaim. She grew up in a comfortably middle-class home with her mother and grandmother, and in particular moments in her text the reader glimpses how Beals perceives her own class position—she calls the soldiers of the Arkansas National Guard "hayseeds" and "tobacco-chewing . . . clods" and sees herself as equipped for higher education and a career in journalism.26Melba Pattillo Beals, Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), 168, 171. Similarly, Terrence Roberts' came from middle class parents; his mother was from an "upwardly mobile" Little Rock family and she ran a catering business, and her son was an eager, talented student, nick-named "the brain" and "the professor" by his peers.27Terrence Roberts, Lessons from Little Rock (Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009), 30. Raised by a college-educated store clerk and a brick-mason, Carlotta Walls LaNier came from a family of resources both cultural and material; like Beals she had travelled outside the Jim Crow South before high school, and like Beals and Roberts, she was academically prepared for Central High and was confident in the classroom. Although the accounts of LaNier, Roberts, and Beals must here stand in for the class position, social connections, and academic preparedness of the Nine, it is a testament to the group's upward mobility and academic preparation that all of the Nine attended and graduated from college.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault, a prominent news anchor and journalist, speaks of the 1961 integration of the University of Georgia much like her lesser-known peer, Daphne Delk does, in terms of "destiny." During her triumphant senior year at Turner High School in Atlanta—"the school for the Black crème de la crème"—Charlayne Hunter-Gault was editor of the school newspaper, president of the Senior Honor Society and Homecoming Queen.28Charlayne Hunter-Gault, In My Place (New York: FSG, 1992), 87. She was a gem of the "talented tenth," the phrase W.E.B. DuBois coined to describe the class of leaders, "an aristocracy of talent and character," in whose hands DuBois felt the fate of "the masses" lay.29W.E.B. DuBois, "The Talented Tenth," in The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative Negroes of To-Day, (New York, 1903). Hunter-Gault integrated UGA with Hamilton Holmes, a bright young man from a prominent family of black businessmen and doctors who would also go on to become Emory's first black medical student. Heckling mobs and social isolation on campus plagued both Hunter-Gault and Holmes, but Hunter-Gault enjoyed the celebrity her role attracted: she hobnobbed with Lena Horne and Robert F. Kennedy and won recognition in the form of prestigious scholarships and awards.30Hunter-Gault, 205, 211. Hunter-Gault went on to work as a correspondent and reporter for PBS, CNN, NPR, The New Yorker and The New York Times. Her extraordinary accomplishments further complicate her role as a narrator of desegregation. Her memoir, like the others, highlights the challenge of commemorating desegregation in a way that at once honors the young integrators and yet imagines a diverse spectrum of experiences, inclusive of poor students, students who struggled academically, and students whose experiences testify to the enduring systematic problems posed by racism, classism and structural inequality.

Conclusion

Of her first days at Pebblebrook High, Virginia Ward maintained that not all her peers whispered "nigger" as she passed them in the halls. She remembered that some students and teachers "were ready for a change anyway. Some people were ready for a change." Ward's narrative—both a narrative of personal victory and a story of unabated struggle—and those of the many "first children" who have not yet been heard, can serve to deepen our understanding of historical desegregation. Rare is such a patient and ingenious steward of the "beloved community" as Ward, and hearing her voice and that of other desegregators is important to a desegregation history that speaks to our present. Reflecting critically on Brown means accepting that between its visionary promise and its distressing failures lie a host of testimonies and experiences of faith, family, gender and, as this story suggests, class, that must be accorded due attention in assessing Brown's legacy and its future.

|

| Article from Pebblebrook High's BrookSpeak, March 2009. |

Scholars Robert Hayman and Leland Ware call the 2007 Supreme Court decision in Parents v Seattle "a betrayal of Brown" which "slam[med] shut" the door on racial diversity. Thankfully, the case was not to be the "final word on desegregation" that they feared.31Hayman and Ware, 313. Long before the Seattle ruling, individual districts like those in Manchester, Connecticut; La Crosse, Wisconsin; and the Wake County schools of Raleigh, North Carolina, creatively and tenaciously pursued plans that did not rely on race or ethnicity-based student assignments. Rather, the plans placed emphasis on class, implementing busing plans to achieve socioeconomic integration. Memphis, Tennessee, recently saw the largest suburban-urban district merger to date when the Shelby County schools, a mostly white suburban district, and the Memphis city schools, a low-income "majority minority" district, consolidated. The previously impossible—a blending of two district's profoundly separate students—has become feasible. What Memphis and Shelby County officials and citizens will make of this opportunity is not yet clear, but the Seattle decision does not foreclose the possibility of class-based plans that have the potential to effect racial desegregation as well.

Although Brown-era desegregation finally allowed black students to demonstrate, in more than token numbers, how ably they could compete with their white peers when they received consummate preparation and resources, not all black students were poised to flourish in integrated schools. Some of the struggles Ward's narrative describes are all too familiar to students fifty years later.32Russell W. Rumberger and Gregory J. Palardy elaborate on previous findings that "socioeconomic segregation matters" in student achievement; they find that in South particularly "the effects of socioeconomic segregation can only be addressed through policies that attempt to redistribute students among schools or improve the quality of [low-SES] schools." "Does Resegregation Matter?: The Impact of Social Composition on Academic Achievement in Southern High Schools," in School Resegregation: Must the South Turn Back? (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2005), 145. The challenges faced by contemporary students of color are not solely those of de jure racism to which Brown dealt such a blow, they are also the manifestations of structural poverty. Ward's experiences and those of students like her demonstrate the continuing importance of desegregation in the fight for educational equity but also point to the promise of class-based desegregation strategies for all low-income students. Sociologist Orlando Patterson has shown that the economic gap between rich and poor black Americans is even greater than that between rich and poor whites: class and race must together guide education policy, if high-poverty schools and low-income students are ever to get the justice they deserve. Despite the dramatic growth of the black middle class in the decades since Brown, black students are still more likely to attend high-poverty high schools and half as likely to graduate from college.33"The Economic Stagnation of the Black Middle Class," A Briefing Before the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, DC, July 15, 2005. Accessed at http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/122805_BlackAmericaStagnation.pdf on December 9, 2011. Ward's story of individual courage enriches a memorializing tradition that too often forgets the role of class. It also must stand to remind those dedicated to educational justice, that students like Virginia Ward succeeded, in today's terms, "against the odds." With an ear to the stories of first children and the guidance they offer, we might take heart in the fact that although structural poverty appears entrenched beyond remedy, so once did the injustices of Jim Crow.

Recommended Resources

Text

Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Hayman, Robert L., and Leland Ware, eds., Choosing Equality: Essays and Narratives on the Desegregation Experience. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009.

Hunter-Gault, Charlayne. In My Place. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1992.

Kruse, Kevin. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

LaNier, Carlotta Walls and Lisa Frazier Page. A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School. New York: One World/Ballantine, 2009.

Lassiter, Matthew. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics on the Sunbelt South. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Roberts, Terrence. Lessons from Little Rock. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009.

Shircliffe, Barbara. The Best of that World: Historically Black High Schools and the Crisis of Desegregation in a Southern Metropolis. New York: Hampton Press, 2006.

Web

Brown vs. Board of Education Digital Archive. University of Michigan Library. http://www.lib.umich.edu/brown-versus-board-education.

Interview with Daphne D. Delk. Kennesaw State University Archives. http://archon.kennesaw.edu/index.php?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=10.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Interview with Virginia Ward, March 13, 2009. All quotations from Virginia Ward that follow are drawn from this interview, and will not be further noted. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence against Women of Color," in Critical Race Theory: Key Writings that Formed the Movement (New York: The New Press, 1995), 376. |

| 3. | The class politics of white resistance have received thorough treatment in recent scholarship on desegregation. In her history of desegregation in New Orleans, Liva Baker describes the white mothers, called the "cheerleaders," as carrying signs that read "If your [sic] poor, mix. If your [sic] rich, forget it. Some law!" The first ward to desegregate was the "politically powerless, materially disadvantaged Ninth Ward." Liva Baker, Second Battle of New Orleans: The Hundred Year Struggle to Integrate the Schools (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 398. Similarly, in Atlanta, lower-income white parents protested that because they could not move away or choose private education like the "silk stocking crowd," they would be disproportionately affected by desegregation. Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 139. In Charlotte, the CPA (Concerned Parents Association) was composed of "well-heeled whites;" these "upwardly mobile parents" mobilized to prevent their children from being bused away from their well-resourced neighborhood schools. Matthew Lassister, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics on the Sunbelt South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 139-140. |

| 4. | When Brown was decided there were 4,000 segregated school districts in the south; three years later 712 of them were desegregating, sending 300,000 black students to integrate schools. This suggests that the numbers of "first children" across the South, who integrated schools alone or in small cohorts, is in the thousands. Robert L Hayman and Leland Ware, eds, Choosing Equality: Essays and Narratives on the Desegregation Experience (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009), 4. |

| 5. | Crenshaw, 376. |

| 6. | "Brown era" refers to the years bookended by Brown I in 1954 and Milliken v Bradley in 1974, the case that prohibited the use of cross-district busing in instances of de facto segregation and marked the turn away from the dramatic (and largely effective) desegregation remedies of the previous decade. |

| 7. | Barbara Shircliffe, The Best of that World: Historically Black High Schools and the Crisis of Desegregation in a Southern Metropolis (New York: Hampton Press, 2006). |

| 8. | Until the county schools began to desegregate, black students had only one high school to attend, Lemon Street High, in downtown Marietta, the county seat. Cobb County adopted "Freedom of Choice" in 1965, but the county's high schools did not desegregate all at once. South Cobb High, for example, began provisionally desegregating before Pebblebrook High School, and as it was in neighboring Austell, Virginia spent her ninth grade year there before transferring to Pebblebrook, her district school. |

| 9. | Interview with Ann Smith by the author, March 10, 2009. |

| 10. | In 1980, as a result of desegregation, only 37% of black students attended mostly black schools, by the year 2000, that number had grown to 69%, quickly approaching the 1968 numbers for Southern black students. Robert L. Hayman and Leland Ware, eds, Choosing Equality: Essays and Narratives on the Desegregation Experience (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009), 319. |

| 11. | Interview with Daphne Delk by Jessica Drysdale and Jay Lutz, November 7, 2009, Kennesaw State University Oral History Project, Cobb NAACP/Civil Rights Series No. 7. |

| 12. | Jennifer Hochschild, Facing Up to the American Dream: Race, Class and the Soul of the Nation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 44. |

| 13. | Thomas Shapiro, The Hidden Costs of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 6. |

| 14. | Pattillo-McCoy comments that since the 1970s examinations of the black "underclass" have constituted a "research industry" stoked in large part by William Julius Wilson's two seminal works on class and race,The Declining Significance of Race and The Truly Disadvantaged, the latter of which documented the plummeting employment opportunities for black Americans and the widening gap between poor black families and middle class black families. Mary Pattillo-McCoy, Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle Class (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 20. |

| 15. | Pattillo-McCoy points out that obtaining a college degree is a "strict" standard for middle-class membership; a more widely applied rule is that a family earns "two times a poverty-level income," 15. |

| 16. | Gary Orfield and Chungmei Lee, "Historical Reversals, Accelerating Resegregation and the Need for New Integration Strategies," A Report of the Civil Rights Project, UCLA, August 2007. |

| 17. | Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, "African American Women's History and the Metalanguage of Race," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol.17, No. 2, Winter 1992, 252. |

| 18. | Barbara Shircliffe, The Best of That World: Historically Black Schools and the Crisis of Desegregation in a Southern Metropolis (Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2006) and Vanessa Siddle Walker, Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1996). |

| 19. | R. Scott Baker, The Paradoxes of Desegregation: African American Struggles for Educational Equity in Charleston South Carolina, 1927-1972 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006) and Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board and Black America's Struggle for Equality (New York: Random House, 1975). |

| 20. | Liva Baker, The Second Battle of New Orleans: The Hundred Year Struggle to Integrate the Schools (New York: Harper Collins, 1996), Karen Anderson, Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2009), J. Anthony Lukas, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (New York: Knopf, 1985). |

| 21. | Elizabeth Jacoway, Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis that Shocked the Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007), Pete Daniel, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2000). |

| 22. | For example, Peter Irons, Jim Crow's Children: The Broken Promise of the Brown Decision& (London: Penguin, 2002); Charles T. Clotfelter, After Brown: The Rise and Retreat of School Desegregation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004). Jennifer Hochschild and Terry M. Moe, though at different ends of the political spectrum, both demonstrate the marginality of desegregation in the scholarship of education reform and educational equity. |

| 23. | Roberts's words are drawn from the plurality opinion in Parents v Seattle in 2007. Thomas' comments date back to his concurring opinion in the 1995 case Missouri v Jenkins. |

| 24. | Richard D. Kahlenberg, All Together Now: Creating Middle Class Schools Through Public Choice (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001). |

| 25. | Although the issue of re-segregation is a pressing one in both the South and the West and has historically been a persistent problem in the urban North, the context for this paper is the de jure school segregation of the South. |

| 26. | Melba Pattillo Beals, Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), 168, 171. |

| 27. | Terrence Roberts, Lessons from Little Rock (Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009), 30. |

| 28. | Charlayne Hunter-Gault, In My Place (New York: FSG, 1992), 87. |

| 29. | W.E.B. DuBois, "The Talented Tenth," in The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative Negroes of To-Day, (New York, 1903). |

| 30. | Hunter-Gault, 205, 211. |

| 31. | Hayman and Ware, 313. |

| 32. | Russell W. Rumberger and Gregory J. Palardy elaborate on previous findings that "socioeconomic segregation matters" in student achievement; they find that in South particularly "the effects of socioeconomic segregation can only be addressed through policies that attempt to redistribute students among schools or improve the quality of [low-SES] schools." "Does Resegregation Matter?: The Impact of Social Composition on Academic Achievement in Southern High Schools," in School Resegregation: Must the South Turn Back? (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2005), 145. |

| 33. | "The Economic Stagnation of the Black Middle Class," A Briefing Before the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, DC, July 15, 2005. Accessed at http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/122805_BlackAmericaStagnation.pdf on December 9, 2011. |