Overview

This article explores the life and archives of Ruth Coker Burks, an Arkansas woman who was a caregiver and AIDS activist from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Arkansas. Newspaper profiles, television interviews, and social media posts have both celebrated and contested Ms. Burks’ efforts as the ‘Arkansas Cemetery Angel.’ Burks’ memoir and her rich, if fragmentary, archival materials shed light on the gendered construction of care work and the lived experience of the AIDS epidemic. At the same time, her legacy illustrates the complexity of AIDS memory.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

Introduction

Ruth Coker Burks (born Frances Ruth Coker in 1959) is an Arkansas woman who was a caregiver and AIDS activist in central Arkansas from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In 1986, when Burks began her informal care work, she was a mid-twenties single mother who sold timeshare condominiums on Lake Hamilton near her hometown of Hot Springs in central Arkansas. Over the next few years, her informal end-of-life care expanded into daily care work, AIDS activism, and education. Newspaper and magazine profiles, television interviews, a popular memoir, and social media posts have documented her efforts as the ‘Arkansas Cemetery Angel’ (we will refer to Ruth Coker Burks as Ruth since this is how she is named in her memoir and in most press coverage). Laudatory media coverage also led to pointed criticisms of the limits of Ruth’s efforts and to potential flaws in her memory. Rather than evaluating the accuracy of Ruth’s account or those of her critics, this article investigates what her rich, if fragmentary, archival materials, along with her published memoir and newspaper accounts, can reveal about care work, gender, and the lived experience of the AIDS epidemic in Arkansas. More broadly, it begins to address what the publicity (and controversy) around Ruth’s life story offers the study of queer memory in southern spaces.

Ruth’s career as an AIDS caregiver and activist began with a case of mistaken maternal identity and a contested family cemetery. As described in newspaper profiles and her memoir, All the Young Men (2020), in 1986, while visiting a friend in the hospital in Little Rock, Arkansas's capital city, Ruth noticed a neglected patient, Jimmy, who was dying of complications from AIDS. When she went into Jimmy's hospital room, he mistook Ruth for his mother, who refused to visit him. After she confronted the nursing staff, who largely avoided Jimmy's room and failed to convince his mother (over the phone) to come to visit her dying son, Ruth returned to Jimmy's room. And it was as his ‘mama’ that Ruth sat by his bedside for hours, holding his hand and comforting him as he died. This moment of assumed maternal identity marked the beginning of Ruth's decade of informal care work.1Ruth Coker Burks and Kevin Carr O’Leary, All The Young Men: A Memoir of Love, AIDS, and Chosen Family in the American South (New York: Grove Press, 2020), 3–11; Michael Garofalo, “Lessons in Love,” StoryCorps, December 5, 2014, https://storycorps.org/podcast/storycorps-449-lessons-in-love/; David Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel,” Arkansas Times, January 8, 2015, https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2015/01/08/ruth-coker-burks-the-cemetery-angel.

Alongside care work and public activism, Ruth provided a final resting place for some men she cared for in the Files Cemetery in Hot Springs, an hour's drive southwest of Little Rock in the Ouachita Mountains. It was for Jimmy, who had mistaken Ruth for his mother, that she turned to Files Cemetery.

From the first chapter of Ruth’s memoir, the Files Cemetery is described as a site of commemoration, refuge, and conflict.2Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 11–14. In the following decades, this cemetery has become an essential site of LGBTQ+ memory in Arkansas. Layers of informal commemoration at the Files Cemetery and Ruth’s fragmentary archival record speak to the kinds of alternative archives of AIDS activism—beyond the public sphere—that Stephen Vider has examined in his discussion of community caregiving during the AIDS epidemic as part of his more extensive study of the importance of domestic spaces in LGBTQ+ politics in the United States.3Stephen Vider, The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2021). As far as we know, the Files Cemetery is one of only a few cemeteries in the United States that became a documented resting place for people who died during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.4Two other documented final resting places for those who died during the HIV/AIDS epidemic are the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC and the Hart Island Potter's Field in New York City. The Files Cemetery operates at a much smaller and more informal scale than either of these.

There also is scattered but evocative evidence of continuing engagement with the Files Cemetery as a space for queer memory-making. Facebook posts from March 2019 record how the drag troupe, the Arkansas Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence: The Abbey of the Hillbilly Harlots, cared for the cemetery’s grounds and planted rose bushes. A series of photographs of the Files Cemetery taken at regular intervals from spring 2020 to fall 2024, which are part of a forthcoming donation to the Center for Arkansas History and Culture, reveal earlier layers of informal commemoration (including notes, beer bottles, Mardi Gras beads, and devotional objects) near the resting places of some of the men. In 2020, a grave was added to the cemetery (of which Ruth was unaware.) Some of these later commemorative efforts at individual graves did not involve Ruth and were potentially enacted by local critics of Ruth, as evidenced by one stone that was partially funded by a critical host of a YouTube podcast.

Praise extended to the national and international levels. The first prominent news article on Ruth, which predated the Arkansas Times' profile, was a twelve-minute interview with NPR's StoryCorps in 2014. The December 7, 2020, issue of People magazine featured a glowing article, “They Call Me the AIDS Angel.”5Jason Sheeler, “They Call Me the AIDS Angel,” People, December 7, 2020. Exemplifying Ruth's newfound fame, the Guardian published an article on February 3, 2021 titled, "The Aids Angel: How Ruth Coker Burks Comforted Dying Gay Men." That same year, however, the Arkansas Times published a more critical piece by Austin Gelder about a “missing monument.” Gelder's piece centered on accusations that Burks had exaggerated some of her claims and failed to establish a much-discussed monument at the Files Cemetery in honor of those for whom she had cared.6Austin Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument,” Arkansas Times, July 8, 2021, https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2021/07/08/ruth-coker-burks-and-the-missing-monument. National press coverage trended from the laudatory to the skeptical with pointed questions about Ruth's claims about the number of men for whom she cared, the number of gravesites at the Files Cemetery, and her contested ownership of the cemetery.7Alexander Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men,” NBC News, October 29, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/doubts-surround-viral-story-aids-angel-says-helped-hundreds-dying-men-rcna4163. These critiques came largely from residents of Hot Springs, some of whom knew Ruth, some of whom wanted a more thorough history of the events, some who are invested in the history and its public telling, and also those who feel that her version of events is somehow maligning the city. A YouTube podcast, RUTHLESS: The Real Story Behind the ‘Cemetery Angel of Arkansas’ is representative of this critique and is discussed in more detail below. In the wake of this praise and criticism, the Center for Arkansas History and Culture at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock has collected Ms. Burks’ archival materials in an ongoing effort to preserve LGBTQ+ history in Arkansas. The CAHC's archival work complements that of Invisible Histories—an organization who "believes archiving is resistance to oppression and history leads to liberation"—to document queer histories and spaces of memory in the southern United States.8"Invisible Histories." Accessed January 3, 2025. https://invisiblehistory.org/.

This article discusses the history of Ruth's care work and activism in central Arkansas in the broader context of scholarship on gender and care work during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We will survey the gendered construction of care work and motherhood in Arkansas in Ruth’s memoir and archival materials. Then, we will tackle the life histories of the predominantly white and Latino working class and rural men she cared for and what her archive—with its evocative fragments and enduring silences— reveals about the lived experience of the AIDS epidemic for some people in Arkansas. We conclude with Ruth’s critics and what her story can teach about the contested memory of the AIDS epidemic. This article does not attempt to evaluate the accuracy of the claims of either Ruth or her local critics, but rather examines the possibilities and limits that her archive, and the published materials about her, open up. The historical importance of Ruth’s care work and the validity of some of the criticisms of her are not incompatible. Rather than a binary understanding, we are interested in what Ruth’s archive reveals about the history of the AIDS epidemic and the construction of the role of the idealized caregiver for some women in Arkansas.

Care Work and AIDS Activism in Arkansas

Ruth was one of many women across the United States who played leading roles in AIDS activism and care. As the ACT UP Oral History Project states, “Women were an integral part of the AIDS crisis—first, and foremost, as People with AIDS, but also as leaders of the AIDS Activist Movement, and as caregivers.”9“Women and AIDS,” ACT UP Oral History Project, digital archive, https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/women-aids. Ruth’s trajectory reflects what scholars have argued was the complex array of personal, political, social, and spiritual motivations behind many women’s activism during the AIDS epidemic in the United States.10See, for example, Ulrike Boehmer, The Personal and the Political: Women’s Activism in Response to the Breast Cancer and AIDS Epidemics (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000); Angelique Harris, “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change: Love, Anger, and Solidarity in Black Women’s AIDS Activism,” Women, Gender, and Families of Color 6, no. 2 (2018): 181–201; For a more expansive history of women’s activism in the United States, see Dawn Durante, ed., Women’s Activist Organizing in US History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2022).

Ruth was a single mother who sold lakeshore timeshares in Hot Springs when she began her informal care work. Her work's flexible and commission-based practices facilitated Ruth’s initial care work. AIDS activism and end-of-life care were not how recently divorced Ruth planned to spend her twenties and early thirties. “All I want sometimes is to be a wife and be in the Junior League.”11Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 74. While Ruth did not come from a well-off background, she hoped to advance in the social scene of Hot Springs. Ruth’s care work encompassed a shifting range of activities from 1986 to 1995. Initially, she focused on visiting the hospital, comforting dying men, and providing supplemental food for those still alive.12Burks and O’Leary, 62; Paula Cocozza, “The AIDS Angel: How Ruth Coker Burks Comforted Dying Gay Men,” The Guardian, February 3, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/feb/03/aids-angel-ruth-coker-burks-dying-gay-men. As she described at one point (she had started dumpster-diving to get adequate cooking supplies), “I could be like this little grocery-delivery person.”13Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 96. Word of mouth drove her first few years of care work as anxious Little Rock and Hot Springs hospital staff contacted her. “More calls started coming. I guess the nurses and doctors all went to the same places to drink and unwind because I later found out they got to talking. ‘Oh my God, we had this insane woman come in, and she went right in the AIDS patient’s room.’ . . . I had two calls that first month, which I thought was crazy. Then three the second.”14Burks and O’Leary, 24–25.

This soon shifted to men calling her directly, either for themselves or for a friend or loved one. As Ruth notes, by 1988, this “network of calls from the hospitals and gay men giving out my number” kept her more than busy, along with caring for her young daughter and trying to make a living.15Burks and O’Leary, 54, 83. It is important not to reify the assumption that persons with HIV/AIDS were always gay men, even if that is often how Ruth discusses her experiences in central Arkansas in her memoir. Ruth’s archive and the ambiguities surrounding the Files Cemetery underline the importance of not projecting contemporary categories onto the past and respecting privacy in the telling of these histories.

From 1986 to 1989, Ruth worked quietly, and from 1989 onwards, she was much more public in attempting to raise awareness and draw local media attention to the AIDS epidemic in central Arkansas. Building on her connections to some of “the town elders” of Hot Springs, Ruth also gave talks at Rotary Clubs across Arkansas and quietly facilitated donations from well-to-do residents of Hot Springs. In her description of one of her early speeches at Rotary, “I talked about the people with AIDS in town, how they needed food and access to care, but what we mainly needed was education.”16Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 125, 129–134, 184, 257. Formalizing her activism, Ruth assisted Norman Jones, who ran the Arkansas non-profit, Helping People with AIDS (HPWA.) Ruth’s work with HPWA encompassed everything from the distribution of accessible sex education materials to creative publicity efforts, including the production of humorous T-shirts with the phrase “I believe in Jesus. Do you?” transformed into “I DO. DO YOU?” about safer sex practices.17Burks and O’Leary, 270–271.

The sharply diverging reactions to Ruth in the present-day echo in her recollections of care work and AIDS activism from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. Ruth claims that initially, she was perceived as a prim “‘church lady’” by many of the men she cared for. However, she remembers that to most of Hot Springs, she was viewed as “this insane woman” and “that crazy Ruth Coker Burks,” who wouldn’t stop talking about AIDS and gay rights.18Ruth Coker Burks, "All Her Sons: The Cemetery Angel," interview by Seth Doane, Video, December 1, 2019, CBS Sunday Morning, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/all-her-sons-ruth-coker-burks-the-cemetery-angel/; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 24, 94, 156.

Along with public-facing activism, Ruth’s informal hospice care evolved from providing company at the bedside of dying men to helping ‘her guys’ live as long as they could by securing housing assistance, filling out death certificates, seeking social security payments, filling AZT prescriptions at often hostile local pharmacies, HIV testing, and ultimately AIDS education.19Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 57–58, 72, 81–83, 86–88, 112–113. Ruth regularly visited hospitals in Hot Springs and Little Rock and frequently cared for people in their homes. At times, she appears to have operated as an informal pharmacy herself, distributing leftover AIDS medication across central Arkansas.20Garofalo, “Lessons in Love”; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 173. These shifts did not mean she stopped providing personal daily attention. For example, in her time with one of the men for whom she cared, Chip, she visited daily, fed him, bathed him, and read him the newspaper.21Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 234. In his study of queer public history and the home, Vider challenges the often-presumed division between political action (outside of the home) and care work (inside the home). Rather than framing the home as a space away from politics, Vider argues that the home and the care for people with AIDS in their own homes constitute an essential site for activism.22Vider, The Queerness of Home, 179–213. The contours of Ruth's care work reflect Vider's argument.

While Ruth’s individualized efforts to keep ‘her guys’ fed are distinct from the more extensive history of food justice organizing in the twentieth-century United States that Emily Twarog studies in Politics of the Pantry (2017), food was at the center of Ruth’s work, especially in the late 1980s, and her subsequent gendered construction as a caregiving angel.23Emily E. LB. Twarog, Politics of the Pantry: Housewives, Food, and Consumer Protest in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). In early media profiles from 2014 and 2015, Ruth estimated that she cared for "nearly 1,000 people" and "hundreds of dying people" from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s.24Garofalo, “Lessons in Love”; Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel.” As discussed below, these numbers have been contested. While it is beyond the scope of this article to fully address how Ruth’s efforts intersected with formal and informal care networks in Arkansas, there were additional organized efforts, including the important work of RAIN (Regional AIDS Interfaith Network), which was profiled in a 2016 Arkansas Times piece, among others.

Ruth’s unprocessed archival collection at the Center for Arkansas History and Culture provides some indications of how her care work intersected with broader caregiving networks in Arkansas. Specifically, her archives include a binder of letters of recommendation and typed endorsements from prominent community members regarding Ruth’s nomination for the Arkansas Community Service Award, the establishment of an HIV/AIDS program at Levi Hospital, and the nomination of Ruth for the position of Executive Director of the Arkansas AIDS Foundation. In one letter, the assistant director of the American Psychological Association recommended Ruth for the Arkansas Community Service Award with the argument that “Ruth’s efforts in promoting the conference have remained unflagging. Most impressively, Ruth has served without remuneration, preferring that we hire two part-time local coordinators from our community of those directly affected by AIDS. As one of our local coordinators has suffered an unfortunate precipitous decline in health. Ruth has generously stepped forward to assume his responsibilities while insisting that he still receive the full salary offered for the position.” A local attorney wrote in a separate letter of recommendation, “I would like to recommend Ruth Burks as the person to get this program started. Ruth has demonstrated her commitment to the care of those who are HIV positive and we are fortunate to have someone already in the community who is prepared to immediately take on such a responsibility.”25These recommendation letters are part of Ruth's collection donated to and being processed by the Center for Arkansas History and Culture. Box 6, Folder 20, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Ruth's memoirs and archives only get us so far in researching the experience of AIDS in Arkansas and of women activists during the AIDS epidemic. Ruth remembers primarily, but not exclusively, caring for white and Latinx men. Her life story and archival materials tell us little about the impact of HIV/AIDS on Black communities in Arkansas (15.5% of the Hot Springs population in 1990) or the work of Black women in AIDS activism both at the state and national levels. Recent scholarship has drawn attention to the central role of Black women to AIDS activism and care work in the United States. In her influential study of Black women activists, Angelique Harris argues for the importance of the intersecting emotions of love, compassion, community solidarity, anger, and frustration in AIDS activism and care work.26Harris, “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change,” 181–183, 186–188, 191–195.

While this article centers upon Ruth’s life and her account of primarily caring for white and Latinx men, it is critical to acknowledge how racial disparities in healthcare profoundly shaped the history of HIV/ AIDS. Unfortunately Ruth’s archive does not tell us much about the impact of the AIDS epidemic on Black people in Arkansas. However, our study of Ruth’s memoir and archival fragments builds on Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary Edwards’ compelling model of biographical essays in Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times (2018) and Jayme Stone’s 2010 study of Black women as activist mothers in the Arkansas Delta.27Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards, eds., Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, Southern Women: Their Lives and Times (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018); Jayme Millsap Stone, “‘They Were Her Daughters:’ Women and Grassroots Organizing for Social Justice in the Arkansas Delta, 1870–1970” (Memphis, TN, University of Memphis, 2010), https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1238&context=etd. Our examination of the richness and limits of Ruth’s archive expands on these authors’ approach of using various sources to demonstrate women's diverse and multifaceted historical roles.

If contested understandings and expectations of gender run through Ruth’s memoir and archives, and the discrimination experienced by many of the men she cared for, Arkansas’s enduring racial divisions implicitly shaped her narrative and its silences. In the words of Catherine Fosl and Daniel Vivian, “the same race, gender, and class divides that mark US society are evident within LGBTQ communities, making histories of queer people of color, women, and trans people more difficult to access, especially by those who do not identify as such.”28Catherine Fosl and Daniel Vivian, “Investigating Kentucky’s LBGTQ Heritage: Subaltern Stories from the Bluegrass State,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (2019): 221. Ongoing archival projects in Arkansas are beginning to address these histories. The Historical Research Center at the UAMS Library has collected and preserved the papers of Dr. Joycelyn Elders, Director of the Arkansas Department of Health (1987–1993) and Surgeon General of the United States (1993–1994), who played an important role in the AIDS epidemic both in Arkansas and nationally.

To understand Ruth’s story—and what her archives and cemetery mean for queer memory in the southern United States—we must address how Ruth embraced and struggled against an ideal of “southern femininity” in the 1980s and early 1990s. Ruth’s memoir is a record of the constricted gender expectations imposed on her and her strategic use of her identity to help the men for whom she cared. In her 1991 essay, Frances Ross provides a formative background on changing notions of femininity and how women addressed social problems in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Arkansas.29Frances Mitchell Ross, "The New Woman as Club Woman and Social Activist in Turn of the Century Arkansas," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50, no. 4 (1991): 317–351. These norms remained decades later, as Anna Zajicek, Allyn Lord, and Lori Holyfield argue in their article on the women’s movement in northwest Arkansas: “To become activists in the civil rights movement, these women had to challenge the ideals of southern femininity and create a new sense of self.”30Anna M. Zajicek, Allyn Lord, and Lori Holyfield, “The Emergence and First Years of a Grassroots Women’s Movement in Northwest Arkansas, 1970-1980,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62, no. 2 (2003): 155. Ruth also grappled with ideals of femininity while embracing the gendered role of caregiver.

In her memoirs and archival notes, Ruth does not directly discuss feminist politics in Arkansas. However, her complex experiences as a caregiver and activist contribute to what Janet Allured referred to as alternative “wellsprings” of “southern change-seekers” in her study of second-wave feminism in Louisiana.31Janet Allured, Remapping Second-Wave Feminism: The Long Women’s Rights Movement in Louisiana, 1950–1997 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016), 49. Moreover, when we examine Ruth’s experiences, it is vital to consider the historical context of Arkansas in the mid-1980s, a little over a decade after the intense political backlash against the proposed Equal Rights Amendment. As Janine Parry argues, “the Equal Rights Amendment in Arkansas had swiftly moved from being perceived by many observers as ‘virtually assured’ of ratification in January of 1973 to being openly reviled at the next legislative session.”32Janine A. Parry, “‘What Women Wanted’: Arkansas Women’s Commissions and the ERA,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2000): 283. While distinct from Ruth's story, these conflicting political currents indirectly shaped her activism and experiences.

Constructing Care Work and Motherhood in Arkansas

Ruth’s written and archival ephemera record the gendered expectations of care and motherhood often imposed on women in late twentieth-century Arkansas. Her autobiography contains a steady commentary on the contested meaning of motherhood in her life and care work. The figures of abusive mothers, absent mothers, and idealized alternative mothers run throughout the book. Ruth’s deeply damaging mother and her own constant worries that she might cause her young daughter harm through her AIDS work are recurring themes.33Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 100–102. Ruth’s memoir and archives contain glimpses of the range of substitute mothers these dying men sought, including Ruth, the Virgin Mary, and even Dolly Parton.

As mentioned, Ruth's career as an informal caregiver in the mid-1980s began with a case of mistaken maternal identity. With only a few exceptions, the men's families for whom Ruth provided care rejected their sick and dying sons.34Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” “So many arrived [back in Arkansas] thinking Mama would take them back. Sometimes I would go to their homes with them, mostly just to save me a trip of driving back out there when she wouldn’t.”35Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 55.

Alongside this parade of neglectful parents, another narrative of idealized mother figures runs through Ruth’s life history and archives. A letter she wrote to Dolly Parton on August 20, 1993, on behalf of Billy Ray Collins soon after he died, fashioned the beloved country music singer as a substitute maternal figure for the dead man. Ruth wrote the letter thanking Dolly for a picture that she had sent to Billy, a devoted fan. “Billy’s mother never saw the picture or even knew that you had sent it,” the letter begins “You see, Billy’s mother wouldn’t come in his last days. . . . Billy was crushed.” Ruth's letter underlined a profound sense of loneliness: “But in the end, even his friends stopped coming by to see him. They just couldn’t take it. His lover, Paul, and I were the only ones there in the last weeks and minutes of his life, except for you.” Ultimately, Ruth had to tell the dying Billy that his mother would not visit him. “I finally told him that his mother wasn’t coming but that I would be there with him as would Paul. And that he would not die alone. All he said was ‘and Dolly’.” In Ruth’s memory of Billy’s final days, recorded in a letter to Parton, a photograph of the singer was transformed into an icon standing in for Billy’s absent mother.36See, Box 6, Folder 16, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. Billy was certainly not the only one of Ruth’s guys to reach out for their mothers and be denied at the end of their lives. This is a recurring theme in Ruth’s memoir.

This search for an alternative maternal figure is perhaps best exemplified by Ruth’s visits with the men she cared for to that most idealized, and unrealizable, of mothers: the Virgin Mary. They often visited a small grotto at St. Mary of the Springs Catholic Church in Hot Springs. “There’s a statue of the Virgin Mary there,” writes Ruth, “in a red-brick shrine, hidden from the street. She’s on a pedestal, so she looks down on you, but there’s kindness in the stone of her eyes. . . . Whatever their religion, or lack thereof, my guys often like to visit her . . . sit on the brick and talk to her.”37Burks and O’Leary, 232.

All the Young Men

At the heart of Ruth’s memoir, and of recent criticisms of her memory, are the men, including Chip and Billy, who she cared for and those she later buried, such as Jimmy, in the Files Cemetery. Who were the titular ‘young men’ of Ruth’s autobiography, or as some of her critics lament, the lost ‘forty names’ of the Files Cemetery?38Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument.”

Based on Ruth’s account, she cared for hundreds of men dealing with HIV/AIDS in central Arkansas from 1986 to 1995.39Garofalo, “Lessons in Love”; Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Burks, "All Her Sons: The Cemetery Angel.” The ashes of a small number of them are interred in the Files Cemetery. These men had returned to Arkansas in search of care after living in New York or Washington, DC, or when they had left more rural parts of the state for Hot Springs or Little Rock. In Ruth’s telling, many of these young men only reluctantly returned to Arkansas for care that their families denied them.40Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 30–31, 76–77. “My guy who made it all the way to DC,” wrote Ruth upon visiting Chip’s grave, “only to end up in the place he’d escaped from.”41Burks and O’Leary, 343.

She cared for primarily working-class (sometimes indigent) young white and Latino men. Specifically, Ruth’s memoir, archives, and interviews record her work with numerous white country boys from the hills of Arkansas, Mexican immigrants in Hot Springs, and working-class drag queens. Many came from Mount Ida, Dardanelle, and other rural towns in central Arkansas.42Burks and O’Leary, 148–149, 165–167. Exemplifying this, Ruth’s beloved Billy, a luminescent drag queen, was “the movie star from Dardanelle.”43Burks and O’Leary, 166. Her guys included everyone from Jim, her first patient; to Tim Gentry, “a hillbilly dandy”; to Roger, whose family tried to wash away his sins in a creek baptism; and to the aforementioned Billy, the charismatic drag queen from Dardanelle who prominently featured in many newspaper profiles of Ruth and her book.44Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Matthew Kincanon, “Ruth Coker Burks Describes Her Lifetime Caring for AIDS Patients to the Gonzaga Community,” The Gonzaga Bulletin, March 1, 2017, https://www.gonzagabulletin.com/news/ruth-coker-burks-describes-her-lifetime-caring-for-aids-patients-to-the-gonzaga-community/article_0e5de906-fdeb-11e6-b294-d72df02858f2.html; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 70. They also included men from Mexico who worked in tree planting or at the Hot Springs racetrack Oaklawn Park, including Angel Mestizo, whom Ruth recounts assisting as he simultaneously sought medical care and to avoid deportation.45Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 274–277. The marginalized status of many of these men led them to Ruth, who, as she frequently reminds her readers and interviewers, lacked any formal medical training. As Paul Wineland, Billy's former partner, notes in the 2014 StoryCorps interview, "You were the only person that we could call. There wasn’t a doctor. There wasn’t a nurse. There wasn’t anyone. It was just you."46Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.”

Occasionally, Ruth did comment on the class divisions. She provided concise descriptions in her efforts to keep her childhood friend, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton, informed about the AIDS epidemic: “But I knew he didn’t know the gay men I saw—the poor, the rejected, the ones with nobody to care for them.”47Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 92. In discussing a professional ballet dancer whose partner came home to die in Arkansas, Ruth described “this ballet dancer who seemed so out of place and of a different class than the Hot Springs guys.” Ruth remembers the drag queens she saw at Our House in Hot Springs as goddesses who transformed the city. “The performers came and went . . . It was like Dynasty, but that was absurd because we were in Arkansas, which meant these people didn’t have the means to have a fabulous life. But there they were in fabulous gowns. . . . They were goddesses. The idea that I could breeze by someone like this in Hot Springs.”48Burks and O’Leary, 161, 267.

Not all of the men lacked political or social connections. Chip exemplifies this. While he was from Glenwood, which Ruth described as “one county over from Hot Springs and about forty years behind,” Chip had enjoyed a rising career working for the Democratic Party in Washington, DC. Chip lived with Ruth and her daughter for a few weeks, and she cared for him as he died.49Burks and O’Leary, 230, 233–235. This simultaneous intensity and brevity helps explain some of the gaps in her detailed knowledge of these men: “I felt at home, yet still at a distance from what these men were going through.”50Burks and O’Leary, 53. Ruth often provided daily care for weeks or months before their families sometimes stepped in for their last few days of life.51Burks and O’Leary, 260–266.

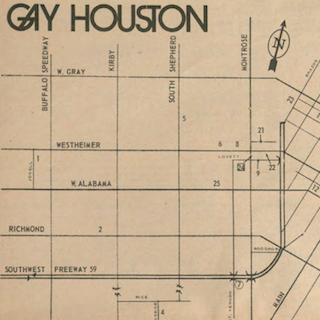

While Arkansas was the site of flight and reluctant return in Ruth’s memoir, Hot Springs served as a refuge for many rural gay men. At the gay bar Our House, “almost all the regulars had left their hometowns to create their own lives here in Hot Springs.”52Burks and O’Leary, 5, 37, 166. For a fuller queer history of Arkansas, see Brock Thompson, The Un-Natural State: Arkansas and the Queer South (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010).

If Hot Springs was a refuge, the Files Cemetery emerged as a site for queer memory. Flagging the commemorative importance of this small cemetery, Ruth says “I wanted them to be counted, to have their lives matter, and I wanted them to have control over their destinies, no matter how limited they might seem to others. If I felt they were strong enough, I brought them to Files Cemetery and asked them to tell me where they’d like to be buried.”53Burks and O’Leary, 58.

A significant challenge of working with Ruth's archives and autobiography is the enduring ambiguities surrounding the number of cremations interred in the Files Cemetery either by her from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, or in the following years as the cemetery became informally associated with LGBTQ+ memory in Arkansas. Estimates of the number of men whose ashes Ruth interred range from five to approximately forty. In her early interview with StoryCorps, Ruth stated, "I’ve buried over forty people in my family’s cemetery because their families didn’t want them."54Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” As one longtime resident of Hot Springs, Tim Looper, notes, there are five identifiable graves of men who died during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and he remembers explicitly going to six funerals there.55Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” Ruth has long maintained that dozens of other cremations have been interred at Files; she mentions fifteen names in her memoir. She insists that given the passage of time and her health problems, she does not remember the names of all the men she cared for.56Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” Moreover, she claims that initially in the 1980s, she concealed what she was doing in the Files Cemetery so that those who would have opposed burying abandoned people associated with AIDS there would not find out.57Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 27–28. Further complicating the matter, Ruth claims that she started to receive anonymous ashes in the mail once she was interviewed about HIV/AIDS in local news outlets, and she proceeded to inter these ashes as well.58Burks and O’Leary, 133–136. Finally, the ashes of people Ruth did not know personally have also been interred at Files, as it became a potent space of LGBTQ+ memory. During an August 2020 visit to the cemetery, Ruth noticed a recently added memorial to a queer-identifying young man whom she had never met.

Ambiguity, anonymity, and informality have been central elements of Ruth's work from the beginning. In response to praise during her StoryCorps interview, Ruth said, "You know, they always say 'fake it ‘til you make it,' and I faked my way through the whole thing. I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t know anything."59Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” Respecting the anonymity of many men is central to Ruth's understanding. "I'd go to an apartment to bring food, and another man would be there,” she writes. "There were people I recognized, though I pretended not to know anything about them."60Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 97–98. Ruth's publisher noted in 2021, "Many of the men Ruth helped and eventually buried approached her asking for anonymity due to not wanting to be outed."61Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.”

The cemetery is a throughline in Ruth's memoirs and interviews. She returns to this commemorative geography at the end of All the Young Men as she narrates the journey from Rogers, in the northwestern corner of Arkansas, where she currently lives, back to her hometown of Hot Springs. “I make my way, finally, to Files Cemetery. The carpet of pine needles crunches under my feet as I make the rounds. The mockingbirds still caw above me. I clear brush here and there on the graves, saying hi to Misty before walking over to see Angel, Carlos, and Antonio.”62Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 344. Alongside its status as a refuge and commemorative space, the cemetery is a site of considerable pain for Ruth, not only in terms of the family conflict that resulted in her contested ownership of many cemetery plots and the memory of the men she buried there, but also the more recent debates over what she did (or did not do) in caring for them.

Ruth's Fragmentary Archive

There are scattered, evocative references to Ruth’s archival materials throughout All the Young Men, whether to her pink leather daybook or to the collection of newspaper clippings related to her successful efforts to mobilize the Downtown Merchants Association of Hot Springs for Worlds AIDS Day on December 1, 1993.63Burks and O’Leary, 154, 337, 339. Her fragmentary archive complements recent public history scholarship on queer history and memory in rural areas of the United States. For example, a 2019 special issue on “Commemorating Queer History" in The Public Historian explored how museum exhibits and historical sites, especially in smaller towns and more rural areas, engage queer history.64See Rebecca Bush, “Woman, Southern, Bisexual: Interpreting Ma Rainey and Carson McCullers in Columbus, Georgia,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (2019): 94–115; Christopher Hommerding, “Queer Public History in Small-Town Wisconsin: The Pendarvis Historic Site and Interpreting the Queer Past,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (2019): 70–93; Fosl and Vivian, “Investigating Kentucky’s LBGTQ Heritage.” As Christopher Hommerding argues, such histories in non-urban areas “[give] lie to the notion that queerness outside of urban centers was historically hidden, invisible, and cut off from queers in other locations.”65Hommerding, “Queer Public History in Small-Town Wisconsin,” 73. Moreover, public historians such as Fosl and Vivian have foregrounded the challenge of “an uneven, often spare historical record” and the need for “better geographic representation” of queer histories in southern spaces.66Fosl and Vivian, “Investigating Kentucky’s LBGTQ Heritage,” 221–222.

In 2022, Ruth donated her archival materials to the Center for Arkansas History and Culture (CAHC) in two batches. The first, more significant donation of materials primarily consisted of biographical and professional information, including planners, personal writing, news clippings, Christmas cards, and scattered photographs from Ruth’s activism and travels in the 1990s. This also included ephemera such as AIDS education t-shirts, drag ball gowns (one of which Ruth wore to Bill Clinton’s first inaugural ball), and the final pottery urn from Dryden Pottery that Ruth never used. The second, smaller donation comprised photo albums, newspapers, magazines, and All the Young Men publication materials. We wish that Ruth had kept better records, but this is the regrettable reality of many archives. Perhaps a better question than why Ruth did not keep better records is what this rich, if incomplete, archive can tell us about the history of HIV/AIDS.

Ruth’s daily planners illustrate the simultaneously rich and fragmentary nature of the collection. The planners in the archival collection include more blank pages than written ones, with some pages marked with only a single name. These fragmentary entries are mundane, a day-to-day account of an individual woman’s hopes and fears. Many are simple notes or reminders, the importance and context coming from either conversation with Ruth or other external sources.

Ruth’s archive reveals what it must have felt like in those difficult early years when she claims she primarily acted alone. As she puts it in the epilogue of her autobiography, “There was no one behind me. I had no choice but to help them.”67Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 343. David Koon began his 2015 profile of Ruth in the Arkansas Times as “one lonely person” attempting to “budge the vast stone wheel of apathy.”68Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel.” This theme of isolation and hostility runs throughout her memoir. As Ruth notes of one church supper, other parishioners “eyed me suspiciously, but they always eyed me suspiciously, even before I was the town pariah.”69Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 152.

But Ruth was not the only individual caring for AIDS patients in central Arkansas. All the Young Men can be read as a record of “the town elders” of Hot Springs who quietly assisted her. This is best exemplified by Clay Farrar, a prominent Hot Springs lawyer. Clay introduced Ruth to a network of Rotary Clubs where she spoke about her care work and AIDS activism and connected with prominent men who were willing to provide support quietly. Several bankers in Hot Springs occasionally assisted Ruth with monetary donations or by requesting favors in the medical profession.70Burks and O’Leary, 182–184, 257–258.

Certainly, a range of individuals and non-profits attempted to help those dealing with HIV/AIDS in Arkansas in the 1980s and early 1990s; however, Ruth’s searing memory but factual inaccuracy in insisting that she acted alone evokes the experience of the HIV/AIDS epidemic for the men she cared for, many of whom—working class, indigent, and abandoned—were from the hills of Arkansas or were Mexican immigrants far from their families. These men were on society’s margins in multiple abject ways. As Ruth describes visiting Angel in the hospital, “Angel and I smiled at each other, together in our lonely place.”71Burks and O’Leary, 277.

This sense of isolation is also represented in Ruth’s archival materials, for instance, in two poems she wrote in the early 1990s, “Shades of Black” and “THIRTYONE.” In writing about her first patient, Jimmy, in “Shades of Black,” the death Ruth recalls is sudden and lonely; there is only Ruth and a dying man crying out for his absent mother. Ruth went into the room alone, held this man’s hand, watched him die, and walked out of the hospital room alone. “Remembering the day that brought me here. He was the first one who just died. Right then, right there. I walked into his room, he took my hand, he nodded and then he died.”72See, Box 6, Folder 16, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

In “THIRTYONE,” the sense of isolation is deployed in anger against society and religious institutions. Ruth writes: “He’s 31 and dying of a disease that not so long ago was God’s revenge, punishment for THEM. While Ruth was sharply critical of the hostility of many religious institutions in Arkansas from the mid-1980s and mid-1990s, she remembers her care work and activism relative to her religious faith. As she has repeated in conversations with us, “I never lost my faith; I just lost faith in everyone else’s faith.”73See, Box 6, Folder 16, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Criticism in Context

In time, media coverage of Ruth shifted from the laudatory into two overarching criticisms. First, Ruth either kept shoddy records of the men whose ashes she interred in the Files Cemetery or was guilty of exaggerating the number she cared for or buried. Second, she has either been unwilling or unable to put up a monument to these men at the Files Cemetery despite advocating for a memorial for years. Some of her critics suggest that a successful GoFundMe campaign (to raise money for a cemetery memorial and Ruth’s medical bills) was entirely used for the latter purpose and not for the former. For example, in a 2021 piece, the Arkansas Times journalist Austin Gelder discussed how there was not yet a memorial, local disappointment in the limited impact of Ruth’s newfound celebrity on Hot Springs, and debates over ownership and oversight of the Files Cemetery. In a subsequent piece for NBC News, Alexander Kacala expanded on these concerns over funding, management of the Files Cemetery, and local disappointment (and anger.) Kacala also suggested that Ruth may have exaggerated or even fictionalized some of her claims, particularly regarding the number of men for whom she cared.74Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” It is important to note that in late 2022, Ruth arranged for a monument to be constructed and delivered to the Files Cemetery.

As Gelder notes, most of her critics still “commend Burks . . . [and] don’t want to detract from her good deeds” while insisting on clarity.75Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument.” In turn, Kacala surmises that beyond the good deeds that Ruth did in the 1980s and early 1990s, “over the years either she or the media have sensationalized the story for some sort of gain.”76Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” Some in Hot Springs are more critical, including Robert Klintworth, a former friend of Ruth who cared for the Files Cemetery for many years (Klintworth provides much of the criticism in both the Arkansas Times and NBC News pieces). Klintworth claims he and his partner, Paul Wineland (who was Billy's partner before his death), cared for the cemetery and provided Ruth with significant assistance in remembering details and names for her book, but that the rewards of the “book deal, a movie deal, and international recognition” have accrued to Ruth alone.77Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument.” Paul Wineland was also central to the 2014 StoryCorp profile, which fed the media's interest on Ruth’s story.

Along with Klintworth, Tim Looper cared for the cemetery for several years after 2015. Looper also is one of Ruth’s prominent local critics, and has argued that Ruth exaggerated her narrative and/or does not remember events accurately.78Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” Looper maintains, for instance, that Ruth’s first hospital visit occurred in Hot Springs and not in Little Rock, as she writes in her memoir. According to Ruth, some local drag troupes have also provided informal care for the cemetery. In 2023, Hot Springs resident Jim Thompson began to care for the seemingly neglected cemetery, as reported by the local news.79Rolly Hoyt, “One Man’s Mission Helps Restore a Site of Arkansas Cemetery Holding Remains of AIDS Victims,” THV 11, October 26, 2023, https://www.thv11.com/article/news/local/arkansas-files-cemetery-aids-restoration/91-39e9dad1-7ece-4244-b854-4e1d2091c5bc.

A June 2024 YouTube video podcast, RUTHLESS: The Real Story Behind the ‘Cemetery Angel of Arkansas’ alleges to uncover the “scam” perpetrated by the “grifter” Burks. The three-hour video is a sensational retelling of the 2021 Arkansas Times article. Looper is the principal source and the recurrent themes include the alleged exploitation of gay deceased men for fame and fortune, the accusation of profiting from a never-constructed (but since built) memorial, the flagging of factual errors and inconsistencies in the memoir, Ruth’s alleged failure to recognize other individuals and entities who provided aid, and a general sense that her version of events has disparaged Hot Springs and Arkansas. Posted comments about the video are overwhelmingly critical of Ruth, but it is beyond the scope of this article to evaluate these claims.

The CAHC is working to process Ruth's and others' archival papers from these years. However, it would take a large research budget (and a significant scholarly team) to, 1) carefully and responsibly reconstruct the life histories of the men buried in the Files Cemetery, 2) locate the interred cremations within the Files Cemetery with both precision and respect for anonymity, and 3) carefully and empathetically adjudicate the conflicting claims by drawing on state and local records. Complicating any research efforts is the reality that almost all of the direct witnesses of what Ruth did are long dead, and the remaining few include both fervent supporters and biting critics. These conflicting accounts rely on individual memories of traumatic events that occurred at least thirty years ago.

Many of the critiques voiced in newspaper articles and videos are valid. We too would like to know more about the men's life histories and see the Files Cemetery physically transformed into the commemorative site it already is in the minds of so many. In telling and retelling Ruth's story, it is clear that many details and claims remain constant, alongside some ambiguities and exaggerations. Ruth is not necessarily the appropriate target for all of these legitimate concerns. Or to reframe Kacala’s observation as a question, if elements of Ruth’s story have been ‘sensationalized’ over the years, to what end have they been sensationalized for a reading public in Arkansas and beyond?

Our preliminary research suggests that the presentation of Ruth as an almost saintly figure began with the 2014 StoryCorps interview and the 2015 Arkansas Times profile. In the StoryCorps interview, Michael Garofalo notes, "Ruth is one of those rare people who doesn’t run away from suffering. She runs toward it without hesitation."80Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” David Koon’s article in the Arkansas Times in 2015 was titled, “Ruth Coker Burks, the Cemetery Angel.” A photograph of Ruth overlayed with the text, “St. Ruth,” was the cover story of the initial print edition (the “St. Ruth” title was removed from the online version). It was more often in the headlines of stories, rather than in the body of articles, that she was presented in saintly or angelic terms.

These binary understandings of Ruth, either as a living saint and the Arkansas cemetery angel, or as a fantasist and teller of tall tales, do not map onto the reality of her evocative and fragmentary archive. Returning to the questions we posed at the beginning of this article, what can Ruth’s archive tell us about the history of the AIDS epidemic in Arkansas and the construction of the role of the idealized caregiver for some Arkansas women at the time?

One answer that her archive does provide is that contestation and debate have long been integral to Ruth's care work and activism and that she has always had both enthusiastic supporters and harsh critics. Based on newspaper clippings from her archival donation, the criticism of Ruth and her work began in the early 1990s. In a 1993 letter to the editor published in the Sentinel-Record (Hot Springs, AR) that echoes some of the later criticism, the author states that Ruth “claims too much credit . . . her statistics are out of this world,” and that Ruth made AIDS patients stand out in the cold during a World AIDS Day service. Other local newspaper pieces saved by Ruth from the early 1990s had less to do with Ruth herself and instead reflected rampant prejudice against gay men. An undated letter to the editor states that the author is withdrawing their membership to the Downtown Merchants Association of Hot Springs due to the Association’s support of AIDS Awareness Day since, in the words of the outraged author, “AIDS is a behaviorally transmitted disease and does not need awareness or anything other than saying 'no' to homosexual activity or drug use. How much does it cost to teach that?”81See, Box 6, Folder 2, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Criticisms of Ruth are not the only subject of the news clippings that she assiduously collected. There are several undated articles praising Ruth and her work. These positive assessments from the early 1990s foreshadow the recent praise of Ruth's care work and activism. One letter by Robert Gale (the vice-president of Helping People with AIDS) refuted the claim that Ruth was not the executive director of HPWA, and praised her efforts in that role. At least two articles in Ruth’s collection mention her professional work at her day job at Prudential Lakefront Real Estate.

Ruth’s archival collection includes a binder of letters of recommendation and typed endorsements from prominent citizens regarding Ruth’s nomination for the Arkansas Community Service Award, the establishment of an HIV/AIDS program at Levi Hospital, and the nomination of Ruth for the position of Executive Director of the Arkansas AIDS Foundation. These letters provide further evidence of the sustained care work that she offered. For example, a local attorney wrote that “Ruth has demonstrated her commitment to the care of those who are HIV positive, and we are fortunate to have someone already in the community who is prepared to immediately take on such a responsibility.”82See, Box 6, Folder 20, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

The testimony of some of Ruth’s critics lends credence to her sustained, if controversial, presence. Kacala includes an extended quote from Hot Springs resident Daymon Jones, a long time survivor of the AIDS epidemic in Hot Springs, who is harshly critical of Ruth. In Jones’ own words, “I have contempt for her … She makes it look like my town was hostile to people with HIV. It’s the fact that she has used that stereotype to portray my town and my community as something horrible and that was not the story.” Jones was particularly annoyed at what he saw as Ruth’s pushy methods in attempting to provide him with unwanted help. Again, in Jones’s own terms, “What really got me riled up [was] how she does it. . . . She said, ‘Well you know I can bury you, too, when you die.’ Well Ruth, I have no intention of dying right now, and even if I do, I have a family cemetery. ‘They won’t let you in, you know that.’ Oh yes they will. We discussed this already. She tried to use fear to make herself look like she was somebody that was going to help.”83Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.

Jones’ comments clearly illustrates that some people living with AIDS in Hot Springs found Ruth’s efforts unnecessary and even offensive. At the same time, the anecdote also suggests that by the early 1990s, Ruth was locally well-known for AIDS-related activism and care work and that she regularly discussed her cemetery as a possible final resting place for those excluded elsewhere.

Conclusion

What can we make of the competing media narratives depicting this individual woman to be either a saint, selflessly salving the wounds of AIDS patients, or a sinner, exaggerating what she did and pocketing the cash? We want to argue that the legitimate anger aimed at the incomplete historical record of these men's lives and the decaying state of their final resting place is standing in for a much larger problem—the terrible treatment accorded those dealing with HIV/AIDS in Arkansas in the 1980s and 1990s by many medical institutions, by civil society, by their families, and by religious congregations. As Ruth put it, with hopefulness, “if I sound the alarm . . . the cavalry will come.”84Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 183. Yet the cavalry never arrived, at least for many of the men for whom Ruth cared. These conclusions are born out in the two persistent emotions that weave their way throughout her story: her searing anger at the failure of others to not do more, and her deep, enduring love for these men whom she often only knew briefly at the very end of their lives. This echoes Harris’s influential analysis of the role of a range of emotions in Black women activists' perspective on their AIDS activism, especially the entanglement of love, compassion, and solidarity with frustration and anger.85Harris, “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change,” 191–195.

Maybe this rush to canonize or vilify Ruth is an effort to displace this broader societal failure. Suppose Ruth was an angelic caregiver for those dying of AIDS. In that case, it absolves all those in Arkansas (and elsewhere) who either did nothing or actively discriminated against gay men. In turn, if Ruth was an imperfect record keeper with a shaky memory, she could become the target of all the legitimate anger of how these men were treated in life and death.

The archive of Ruth’s life, activism, and care work, and its fragments offers a much more sobering history of AIDS in Arkansas: a colossal tragedy and a systemic failure. Not a failure on the part of Ruth or the other individuals who, at a tremendous personal sacrifice, helped those dealing with HIV/AIDS, but rather a systemic failure on the part of many medical institutions, state government, and civil society. Returning at the very end of her autobiography to the very beginning of her story (when she walked into Jimmy’s hospital room in Little Rock in 1986), Ruth puts it a different way: “The question I get most, the one I hate, is why I went into his room. And why I helped people. Again and again . . . the answer is, How could I not? The real question is, How could you not?”86Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 345.

Ultimately, it is not a question of what Ruth Coker Burks did (or did not do) to become the Arkansas Cemetery Angel, but rather what the depictions of Ruth as an angel and a saint in print and the media reveals about the memory (and continuing reality) of AIDS in Arkansas. At its most potent, Ruth's memoir and archives—alongside the Files Cemetery—not only illustrate the deep commitment of one inspiring individual, however imperfect, to help those suffering at society's margins, but also provide a glimpse into the lives of the men she cared for, whether in documenting their loneliness, their heroic efforts to live as long as they could, or in their fashioning of substitute mothers and chosen family.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nathan Marvin, Marta Cieslak, and David Baylis for their encouragement, generous feedback, and insights that contributed to the development of this article.

About the Authors

Andrew Amstutz is an assistant professor of history at Queens College, CUNY. He has published articles in Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Philological Encounters, and South Asia. Prior to joining Queens College, he taught at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Jess Porter is executive director of the Center for Arkansas History and Culture, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock's archive. He is a geographer and former chair of UALR's history department.

Phoenix Smithey is the head of special collections and university archivist at the University of Central Arkansas. Smithey is active with the Academy of Certified Archivists, the Society of Southwest Archivists, and the Arkansas Humanities Council. She teaches in the fields of archival management and archival preservation.

Recommended Resources

Burks, Ruth Coker. All the Young Men: A Memoir of Love, AIDS, and Chosen Family in the American South. New York: Grove Atlantic, 2020.

Harris, Angelique. “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change: Love, Anger, and Solidarity in Black Women’s AIDS Activism.” Women, Gender, and Families of Color 6, no. 2 (2018): 181–201.

Jones-Branch, Cherisse, and Gary T. Edwards, eds. Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Thompson, Brock. The Un-Natural State: Arkansas and the Queer South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010.

Web

ACT UP Oral History Project. "Digital Collection." 2002–2015. https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/31/resources/6341.

Center for Arkansas History and Culture. "Collections." Accessed January 16, 2025. https://ualr.edu/cahc/collections/.

Garofalo, Michael. “Lessons in Love.” StoryCorps, December 5, 2014. Podcast, 12:11. https://storycorps.org/podcast/storycorps-449-lessons-in-love/

Invisible Histories. "Digital Collections." Accessed January 16, 2025. https://invisiblehistory.org/digital-collections/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Ruth Coker Burks and Kevin Carr O’Leary, All The Young Men: A Memoir of Love, AIDS, and Chosen Family in the American South (New York: Grove Press, 2020), 3–11; Michael Garofalo, “Lessons in Love,” StoryCorps, December 5, 2014, https://storycorps.org/podcast/storycorps-449-lessons-in-love/; David Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel,” Arkansas Times, January 8, 2015, https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2015/01/08/ruth-coker-burks-the-cemetery-angel. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 11–14. |

| 3. | Stephen Vider, The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2021). |

| 4. | Two other documented final resting places for those who died during the HIV/AIDS epidemic are the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC and the Hart Island Potter's Field in New York City. The Files Cemetery operates at a much smaller and more informal scale than either of these. |

| 5. | Jason Sheeler, “They Call Me the AIDS Angel,” People, December 7, 2020. |

| 6. | Austin Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument,” Arkansas Times, July 8, 2021, https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2021/07/08/ruth-coker-burks-and-the-missing-monument. |

| 7. | Alexander Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men,” NBC News, October 29, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/doubts-surround-viral-story-aids-angel-says-helped-hundreds-dying-men-rcna4163. |

| 8. | "Invisible Histories." Accessed January 3, 2025. https://invisiblehistory.org/. |

| 9. | “Women and AIDS,” ACT UP Oral History Project, digital archive, https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/women-aids. |

| 10. | See, for example, Ulrike Boehmer, The Personal and the Political: Women’s Activism in Response to the Breast Cancer and AIDS Epidemics (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000); Angelique Harris, “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change: Love, Anger, and Solidarity in Black Women’s AIDS Activism,” Women, Gender, and Families of Color 6, no. 2 (2018): 181–201; For a more expansive history of women’s activism in the United States, see Dawn Durante, ed., Women’s Activist Organizing in US History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2022). |

| 11. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 74. |

| 12. | Burks and O’Leary, 62; Paula Cocozza, “The AIDS Angel: How Ruth Coker Burks Comforted Dying Gay Men,” The Guardian, February 3, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/feb/03/aids-angel-ruth-coker-burks-dying-gay-men. |

| 13. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 96. |

| 14. | Burks and O’Leary, 24–25. |

| 15. | Burks and O’Leary, 54, 83. |

| 16. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 125, 129–134, 184, 257. |

| 17. | Burks and O’Leary, 270–271. |

| 18. | Ruth Coker Burks, "All Her Sons: The Cemetery Angel," interview by Seth Doane, Video, December 1, 2019, CBS Sunday Morning, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/all-her-sons-ruth-coker-burks-the-cemetery-angel/; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 24, 94, 156. |

| 19. | Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 57–58, 72, 81–83, 86–88, 112–113. |

| 20. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love”; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 173. |

| 21. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 234. |

| 22. | Vider, The Queerness of Home, 179–213. |

| 23. | Emily E. LB. Twarog, Politics of the Pantry: Housewives, Food, and Consumer Protest in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). |

| 24. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love”; Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel.” |

| 25. | These recommendation letters are part of Ruth's collection donated to and being processed by the Center for Arkansas History and Culture. Box 6, Folder 20, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. |

| 26. | Harris, “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change,” 181–183, 186–188, 191–195. |

| 27. | Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards, eds., Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, Southern Women: Their Lives and Times (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018); Jayme Millsap Stone, “‘They Were Her Daughters:’ Women and Grassroots Organizing for Social Justice in the Arkansas Delta, 1870–1970” (Memphis, TN, University of Memphis, 2010), https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1238&context=etd. |

| 28. | Catherine Fosl and Daniel Vivian, “Investigating Kentucky’s LBGTQ Heritage: Subaltern Stories from the Bluegrass State,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (2019): 221. |

| 29. | Frances Mitchell Ross, "The New Woman as Club Woman and Social Activist in Turn of the Century Arkansas," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50, no. 4 (1991): 317–351. |

| 30. | Anna M. Zajicek, Allyn Lord, and Lori Holyfield, “The Emergence and First Years of a Grassroots Women’s Movement in Northwest Arkansas, 1970-1980,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62, no. 2 (2003): 155. |

| 31. | Janet Allured, Remapping Second-Wave Feminism: The Long Women’s Rights Movement in Louisiana, 1950–1997 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016), 49. |

| 32. | Janine A. Parry, “‘What Women Wanted’: Arkansas Women’s Commissions and the ERA,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2000): 283. |

| 33. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 100–102. |

| 34. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” |

| 35. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 55. |

| 36. | See, Box 6, Folder 16, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. |

| 37. | Burks and O’Leary, 232. |

| 38. | Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument.” |

| 39. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love”; Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Burks, "All Her Sons: The Cemetery Angel.” |

| 40. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 30–31, 76–77. |

| 41. | Burks and O’Leary, 343. |

| 42. | Burks and O’Leary, 148–149, 165–167. |

| 43. | Burks and O’Leary, 166. |

| 44. | Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Matthew Kincanon, “Ruth Coker Burks Describes Her Lifetime Caring for AIDS Patients to the Gonzaga Community,” The Gonzaga Bulletin, March 1, 2017, https://www.gonzagabulletin.com/news/ruth-coker-burks-describes-her-lifetime-caring-for-aids-patients-to-the-gonzaga-community/article_0e5de906-fdeb-11e6-b294-d72df02858f2.html; Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 70. |

| 45. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 274–277. |

| 46. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” |

| 47. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 92. |

| 48. | Burks and O’Leary, 161, 267. |

| 49. | Burks and O’Leary, 230, 233–235. |

| 50. | Burks and O’Leary, 53. |

| 51. | Burks and O’Leary, 260–266. |

| 52. | Burks and O’Leary, 5, 37, 166. For a fuller queer history of Arkansas, see Brock Thompson, The Un-Natural State: Arkansas and the Queer South (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010). |

| 53. | Burks and O’Leary, 58. |

| 54. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” |

| 55. | Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” |

| 56. | Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel”; Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” |

| 57. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 27–28. |

| 58. | Burks and O’Leary, 133–136. |

| 59. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” |

| 60. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 97–98. |

| 61. | Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” |

| 62. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 344. |

| 63. | Burks and O’Leary, 154, 337, 339. |

| 64. | See Rebecca Bush, “Woman, Southern, Bisexual: Interpreting Ma Rainey and Carson McCullers in Columbus, Georgia,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (2019): 94–115; Christopher Hommerding, “Queer Public History in Small-Town Wisconsin: The Pendarvis Historic Site and Interpreting the Queer Past,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (2019): 70–93; Fosl and Vivian, “Investigating Kentucky’s LBGTQ Heritage.” |

| 65. | Hommerding, “Queer Public History in Small-Town Wisconsin,” 73. |

| 66. | Fosl and Vivian, “Investigating Kentucky’s LBGTQ Heritage,” 221–222. |

| 67. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 343. |

| 68. | Koon, “Ruth Coker Burks: The Cemetery Angel.” |

| 69. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 152. |

| 70. | Burks and O’Leary, 182–184, 257–258. |

| 71. | Burks and O’Leary, 277. |

| 72. | See, Box 6, Folder 16, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. |

| 73. | See, Box 6, Folder 16, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. |

| 74. | Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” |

| 75. | Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument.” |

| 76. | Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” |

| 77. | Gelder, “Ruth Coker Burks and the Missing Monument.” |

| 78. | Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men.” |

| 79. | Rolly Hoyt, “One Man’s Mission Helps Restore a Site of Arkansas Cemetery Holding Remains of AIDS Victims,” THV 11, October 26, 2023, https://www.thv11.com/article/news/local/arkansas-files-cemetery-aids-restoration/91-39e9dad1-7ece-4244-b854-4e1d2091c5bc. |

| 80. | Garofalo, “Lessons in Love.” |

| 81. | See, Box 6, Folder 2, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. |

| 82. | See, Box 6, Folder 20, Ruth Coker Burks papers, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas. |

| 83. | Kacala, “Doubts Surround Viral Story of ‘AIDS Angel’ Who Says She Helped Hundreds of Dying Men. |

| 84. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 183. |

| 85. | Harris, “Emotions, Feelings, and Social Change,” 191–195. |

| 86. | Burks and O’Leary, All the Young Men, 345. |