Overview

The work of queer history is also the work of public and local history. Exploring how the queer past enlivens a queer future, Samantha Rosenthal suggests that these histories have the power to give new meaning to the places we call home.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

Blog Post

I recently bought a crumbling old house in a historically gay neighborhood in Roanoke, Virginia. I met my ex-lover in this house five years ago. At the time they lived with a coterie of other young people. They threw raucous queer parties and housed folks who didn't have anywhere else to go.

A few blocks down the street is another building. There, in 1971, a group of young men and women founded the Gay Alliance of the Roanoke Valley (GARV), the region's first gay liberation organization. This building is now a medical office. I come here once a year to see my endocrinologist. He prescribes spironolactone and estradiol to help my body transform into something approximating that of a woman.

The local neighborhood association puts up signs that read, "A Past with a Future." As I see it, the neighborhood's past is rich with gay history, and the future is my transitioning body and the pink, white, and blue flag I fly in the driveway.

Queer history lives here. It's overlapping in the spaces of my neighborhood. It's in the bones of the buildings. Queer ghosts inhabit the walls. Archaeological troves are remnant in the yards. My dog June digs them up with her ready paws and pearl-white fangs. My gender transformation is hitched to the woodwork and to the water pipes of all the apartment buildings where I have lived. People have lived queerly in these spaces. I have bought a home that not only holds the past but makes space for the future—for my womanhood, my motherhood, and for the chosen family I will assemble underneath this roof.

LGBTQ people have long known that our stories are not to be found in the so-called annals of history, and that we have to look in unexpected places to find our past. Lesbians in Roanoke in the 1980s devoted an entire issue of their newsletter, Skip Two Periods, to "Discovering Our Heritage." The writer, "B. F.," wrote about finding her heritage at the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, in Jonathan Ned Katz's book Gay American History, through the National Women's History Project, and in the published letters shared among nineteenth-century women. She also suggested that lesbian history is found in our families. "Write to your grandmother and ask her about her grandmother," she pleaded. Indeed, queer history is present in the way my parents reacted when I first came out, as they referenced a family member who died of AIDS in 1989 and hinted that I might face a similar fate. We carry queer trauma in our bodies. All of us—straight, gay, cis, trans—live in a world shaped by the queer past.

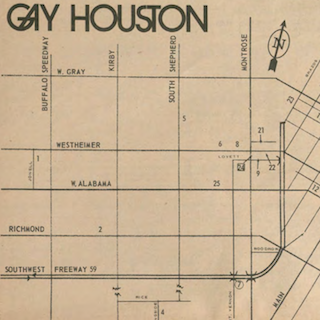

We have the tools to probe this history on the local level. Since the 1970s, queer history projects have flourished across the United States. New archives are forged from the remains stowed away in activists' attics and closets. Oral history collections are assembled from the stories of our elders, talking about what it was like growing up as a trans person in Appalachia in the 1960s, for example. Doing queer history work provides us with the opportunity to bring LGBTQ people together across generations, to talk about what was and what can be, to find new meaning in the spaces of our lives.

Six years ago, I helped found the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project, a community history project that has since engaged hundreds of local people in the process of researching and interpreting queer pasts. This has involved creating a permanent archive in partnership with the local public library system, developing an oral history collection through interviews with our elders, leading monthly walking tours, unveiling digital exhibits, releasing podcasts, and working with local youth on interactive theater and zine-making workshops. This project is how I ended up spending time in this house; it's where I fell in love with a project member who lived here. It's how we know the geography of bars and cruising spaces that once littered the neighborhood, and the all-queer and all-trans houses that still stand. It's how I discovered my gender. Interviewing trans women about their lives, I realized this was also my story. So I came out into the spaces of the project, into the spaces of our city, into a new relationship with queer history. A past with a future.

Every October we celebrate LGBTQ History Month. To me, this month is a reminder that we are still fighting, especially here in the South, for students' right to learn basic LGBTQ history in the classroom. But beyond the metanarrative of what should be taught in school, there are thousands of local queer histories still waiting to be uncovered. This work takes all of us—students, elders, volunteers, professionals. Do you know when the first gay organization was founded in your community? Have you met your trans elders? The work of doing queer history has the power to transform lives. It has the power to give new meaning to the places we call home.

About the Author

Gregory Samantha Rosenthal is the author of Living Queer History: Remembrance and Belonging in a Southern City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

Cover Image Attribution:

Logo of the Gay Alliance of the Roanoke Valley (GARV), Roanoke, Virginia, 1971. Courtesy of the LGBTQ History Collection, Virginia Room, Roanoke Public Libraries.Recommended Resources

Text

Gieseking, Jen Jack. "LGBTQ Spaces and Places." In LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History, edited by Megan E. Springate. Washington, DC: National Park Foundation, 2016.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. Rev. ed. New York: Meridian, 1992.

Rosenthal, Gregory Samantha. "Make Roanoke Queer Again: Community History and Urban Change in a Southern City." The Public Historian 39, no. 1 (2017): 35–60.

Sears, James Thomas. Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Web

"Finding Each Other: Gay and Lesbian Community Organizing in Southwest Virginia, 1980–1985." Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project. April 2018. http://gay80s.pages.roanoke.edu/.

"Oral Histories." Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project. Accessed October 27, 2021. http://lgbthistory.pages.roanoke.edu/oral-histories/.