Overview

In the following excerpt from The Lesbian South, Jaime Harker describes how lesbian feminist authors have reinvented the imagined spaces of the US South through print culture, activism, and intentional communities.

Excerpted from The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon by Jaime Harker. Copyright © 2018 by Jaime Harker. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

Women's Space, Queer Space: Communes, Landykes, and Queer Contact Zones in the Lesbian Feminist South

The middle-aged man sitting in the row in front of me shoved his wife's arm and pointed at two women. "See?!" he said, conspiratorially, derisively. I looked at my friend Cheryl and raised an eyebrow. Where did he think he was, anyway? The Southeastern Conference (SEC) Women's Basketball Tournament audience is filled with lesbians—butches, femmes, sports dykes, some distinguished by a modified mullet, others by their no-makeup, tennis shoes, and jeans uniform, but all united in their obsession with women's basketball.

Of course, the tournament audience includes others besides lesbians; like most queer spaces in the South, lesbians share the space with many other groups—retirees, parents and their tween daughters, and random diehard SEC fans who love their team or really hate their rivals. Yet the SEC Women's Basketball Tournament is a roving capital of the southern sisterhood, and it is anything but subtle, but if you ask the fathers and the busloads of white-haired retirees about all the lesbians they will look at you blankly, whether they noticed them or not.

This is because "the South" has always been an imagined community, based in wish fulfillment and aspiration, that depends upon deliberate unlooking. It excludes populations that, collectively, comprise a majority of the population. It excludes black southerners, who understandably have a more ambivalent relationship to the "sense of place" invested in their subordination. It excludes the many immigrant groups that have made the South their home over the generations—Chinese, Lebanese, Italians, and more recently, Indians, Vietnamese, Africans, Hispanics. It ignores queer southern communities in towns both small and large. In other words, the "sense of place" so beloved by traditional southern literary critics overlooks the actual people in that place.

This tendency to disavow the full complexity of diverse communities in the South has a long, shameful history. The Confederacy imagined a southern aristocracy based on honor and culture, obscuring a white supremacy dependent on stolen slave labor. Post-Reconstruction politics did more than rewrite the cause of the Civil War—it also remade the space of the South: Confederate memorial statues were erected, often in town squares or in prominent public locations, as Jim Crow laws limited the spaces and places African Americans could live, work, and recreate.1For more see, Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies' Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008) and Micki McElya, Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). The fact that these public Confederate monuments still dominate southern spaces, and that their removals provoke intense debate and outcry, suggests how effectively this southern space made inequity seem natural.

The ubiquitous notion of a static, conservative South has led to many unwarranted assumptions about LGBTQ communities and their incompatibility in the South. Gay liberation was framed as an urban phenomenon; gay people leave their inhospitable small towns and regions and build a critical mass in major cities like New York and San Francisco, where their visibility and numbers result in political clout and political influence. Greenwich Village in New York and the Castro in San Francisco were two models; pioneer Harvey Milk encouraged queers across the country to join him in paradise.

This metronormativity has been questioned in studies of rural and southern queer spaces like John Howard's Men Like That, Mary Gray's Out in the Country, and Scott Herring's Another Country. Howard's ground-breaking book challenged the linking of gay identity and urban life, insisting that this bias "at times has denied agency to rural folk, [and] has assumed that nonurban dwellers can't attach meanings to, can't find useful ways of framing, their nonconforming attractions and behaviors."2John Howard, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 14. He argues that "in Mississippi, spatial configurations—the unique characteristics of a rural landscape—forged distinct human interactions, movements, and sites," and that the urban model "incompletely and inadequately gets at the shape and scope of queer life."3Howard, Men Like That, 15. He suggests new models for understanding that queer life, decoupled from both identity and a fixed sense of place.

Scott Herring concurs. He provides a detailed overview of the growing scholarship on queer rural communities, concluding that "these artists and authors pay heed to the 'non-metropolitan' as a dynamic space of inquiry and sexual vitality. Complicating geophobic claims that ruralized spaces are always and only hotbeds of hostility, cultural and socioeconomic poverty, religious fundamentalism, homophobia, racism, urbanoia, and social conservatism, their works question knee-jerk assumptions that the 'rural' is a hate-filled space for queers as they archive the complex desires that contribute to any non-metropolitan identification."4Scott Herring, Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 9. Herring's own work focuses on contemporary artistic portrayals of the rural queer in periodicals, photography, memoirs, and graphic novels.

This work on rural queerness is enhanced by feminist and queer geography, which has provided new paradigms to theorize how ideologies order and impede our understandings of space and how different configurations can remake that sense of space. Jack Geiseking explains that "space is not absolute or fixed in the Kantian sense but constantly produced in how it is all at once created, conceived, and lived."5Jen Jack Giesking, "A Queer Geographer's Life as an Introduction to Queer Theory, Space, and Time," in Queer Geographies: Beirut, Tijuana, Copenhagen, eds. Lasse Lau, Mirene Arsanios, Felipe Zuniga-Gonzalez, Mathia Kryger, and Omar Mismar (Roskilde, Denmark: Museet for Samtidskunst, 2014), 14. Our "natural" notions of space, in other words, are not innocent; instead, as the Women and Geography Study Group argues, "dominant senses of place reflect, in both their form and their content, the meanings given to places by the powerful."6Gillian Rose, Nicky Gregson, Jo Foord, et al., Introduction to Feminist Geographies: Explorations in Diversity and Difference, ed. Women and Geography Study Group (Essex, UK: Longman, 1997), 9. They continue, "A consequence of the way in which very specific senses of place are constructed through the particular images and values attached to them by the socially and culturally powerful, is that senses of place are often highly controversial. Other groups may challenge the senses of place produced by the powerful, and cultural geographers therefore argue that senses of place are often also sites of contestation."7Rose et al., Introduction to Feminist Geographies, 9. This focus on space as a site of contestation serves as a dominant focus of feminist and queer geography. "Space" isn't natural, and it isn't neutral.

Doreen Massey lays out the terms for understanding space beyond the fixed narrative of the powerful. She argues that space is heterogeneous, inhabited by diverse groups of people who often disagree about its functions and purpose. Multiple and relational, space is also open-ended and unfixed. As she explains,

What is special about place is not some romance of a pre-given collective identity or of the eternity of the hills. Rather, what is special about place is precisely that throwntogetherness, the unavoidable challenge of negotiating a here-and-now. . . . There can be no assumption of pre-given coherence, or of community or collective identity. . . . In sharp contrast to the view of place as settled and pre-given, with a coherence only to be disturbed by "external" forces, places as presented here in a sense necessitate invention; they pose a challenge. . . . They require that, in one way or another, we confront the challenge of the negotiation of multiplicity.8Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage Publications, 2005), 140–141.

Massey's insistence that there is no "pre-given coherence" to a space challenges a fundamental assumption about the fixity of the South and rejects the idea that there is some coherent essence of southernness. It constructs space that is always being created in the present moment, negotiating often contradictory perspectives.

Indeed, Massey's notion of "throwntogetherness" allows for radical reimaginations of space: "What I'm interested in is how we might imagine spaces for these times; how we might pursue an alternative imagination. What is needed, I think, is to uproot 'space' from that constellation of concepts in which it has so unquestioningly so often been embedded (stasis; closure; representation) and to settle it among another set of ideas (heterogeneity; relationality; coevalness . . . liveliness indeed) where it releases a more challenging political landscape."9Massey, For Space, 13. The idea of "alternative imagination" of space is a dominant theme in feminist and queer geography. Geiseking privileges the "action of queering: refusing the normative and upsetting privilege for more radical, just worlds, even those not yet imagined,"10Giesking, "A Queer Geographer's Life," 15. to "uproariously alter the everyday spatialities of heterosexuality."11Giesking, 15. These disruptions include interventions in "the built environment" and the "landscapes" we construct to represent "nature."

Though studies of this utopian "act of queering" tend to focus on contemporary, urban interventions, the act of queering was central to utopian reimaginations of rural space in early women's liberation. Creating autonomous women's space and queer space was a central focus of women's communes and the landyke movement, which had particular resonance in the archive of southern lesbian feminism.

Landykes, Communes, and Lesbian Idealization of the Rural

Early women's liberation was long engaged with challenging the patriarchal hierarchies of space, both public and private. Many early protests—the sit-in at Ladies Home Journal, for example, and the burning of undergarments at the Miss America pageant—were forms of performance art that sought to make visible the seemingly "natural" public spaces allowed to women. These demonstrations intended to smash the public/private distinction that had isolated women and made their concerns a personal failing rather than a structural injustice. The creation of temporary spaces of freedom within a larger heteropatriarchal society—like gay bars and women's music festivals—were another strategy to reconfigure space.

Some lesbian feminists opted for more permanent means of escape that involved experiments in living that were, fundamentally, experiments of spatiality. Greta Rensenbrink explains that "separatist communities emerged in urban areas, especially San Francisco and New York, and increasingly on rural land communes across the United States."12Greta Rensenbrink, "Parthenogenesis and Lesbian Separatism: Regenerating Women's Community through Virgin Birth in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s," Journal of the History of Sexuality 19, no. 2 (May 2010): 291. These separatist communities often functioned as "collectives" in urban areas; some of the most important manifestos of the early women's movement emerged from collectives, which formed and reformed with alacrity in the early 1970s. Women lived and worked in the same space, breaking down the notions of public and private, masculine and feminine. Collectives broke down hierarchies within private and public lives, as well. Members often rejected the distinction between intellectual labor and physical labor; in press collectives, for example, women both wrote articles, short stories, and poems and physically printed these pieces—sometimes on mimeograph machines and later on letterpresses they bought and taught themselves how to use. There was deep suspicion about "leaders" of these groups; decisions were collectively and democratically reached. Cooking, cleaning, home repair—all were burdens to be shared equally in the collective. Collective members tried to re-make space to construct new revolutionary models. They also tried to remake economic models. Frequently, only a few of the members of these collectives had "straight" jobs, which were used to support the entire community. Collectives experimented with different models for self-sufficiency to free themselves from the obligations of capitalist patriarchy. Very few women stayed in these collectives for long; manifestos often had more staying power than the intentional communities that produced them.

Some collective experiments sought physical separation from mainstream society. Research has shown the "the country was an 'ideal' or 'fantasy' place for lesbians to live,"13David Bell and Gill Valentine, "Introduction: Orientations," in Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities, eds. David Bell and Gill Valentine (New York: Routledge, 1995), 8. because it seemed to allow for a reinvention of space from the ground up. Sine Anahita explains, "In the early 1970s, the landdyke movement was created when a radical branch of second-wave feminism converged with ideas from the hippie back-to-the-land and other social movements. . . . From the outset, landdykes articulated the connections between ecological and feminist principles. Early activists sought to create a network of land-based communities where ecofeminist principles could manifest in everyday acts to prefigure a lesbian feminist, nature-centered, postpatriarchal future."14Sine Anahita, "Nestled into Niches: Prefigurative Communities on Lesbian Land," Journal of Homosexuality 56, no. 6 (August/September 2009): 724. This geographical experiment allowed for more democratic and communal constructions of space to teach, inspire, provide refuge, and influence the larger culture with guerrilla-type actions. Rose Norman, Merril Mushroom, and Kate Ellison, editors of a special issue of Sinister Wisdom on the landyke movement in the South, explain that "landykes were creating something larger, beyond a couple or a family. They attempted to live out egalitarian and ecological principles, which they saw as the core of female culture. They attempted this within sometimes stark financial, cultural, and psychological limitations."15Rose Norman, Merril Mushroom, and Kate Ellison, "Notes for a Special Issue, Landykes of the South: Women's Land Groups and Lesbian Communities in the South," Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 8. While the landyke movement was national, the editors suggested that the South has always contained a large share of these experimental communities.16Norman et al., "Notes for a Special Issue," 5.

Such movements are controversial and have been denounced as essentialist, white-identified, privileged, and unrealistic, but participants portray them differently. Some are unapologetic in their insistence on a women-only space and cling to essentialist notions of women's innate difference and superiority, but others see the landyke movement as an essential part of their development that allowed for creative rethinking of what is possible in culture, politics, and living. Sarah Shanbaum explained: "We created a closed and separatist environment, and in that closed and separatist environment, we learned and we became strong, and then we broke that like an egg, and went out into the world, and did what it was we wanted to do."17Dee Mosbacher, dir., Radical Harmonies: Woodstock Meets Women's Liberation in a Film about a Movement that Exploded the Gender Barriers in Music (Wolfe Video, 2004). Seeing separatism as a necessary phase that led to a broader inclusiveness is common for participants, and it is a pattern that we see in the archive of southern lesbian feminism as well.

Women's space and women's land were essential for the utopian possibilities they fostered. Greta Rensenbrink argues that "separatists embraced prefigurative politics, seeking to live the future in the present and working to create communities and local cultures that anticipated a utopian dream."18Rensenbrink, "Parthenogenesis and Lesbian Separatism," 292. As one landyke participant explained in the documentary Lesbiana:

We were actively rethinking the world. Each time I walked out of the bar, I felt like I was crossing a zone from a fictional world—the life in the bar—into reality—life in the city. And that is how I developed this notion of reality versus fiction. Meaning that women's reality was perceived as fiction by men, and what we called reality, was in fact the accumulation of masculine subjectivity that has been working for centuries establishing laws, traditions, etc. And we called that "reality," but it was nothing more than the male version of reality carried through the centuries. During that time, I was writing two pages. On one page I was trying to figure out the male system, a horrible system, detrimental to women: patriarchy. I was trying to figure out its strategies and its tactics, and how it evolved and was persistent to this day. And on the other page, I was writing about desire, utopia, beauty, pleasure, and everything I was discovering with other women. This is how I stayed in touch with the reality of patriarchy and still I could take flight, into love, lust, sisterhood, and all the discoveries I was making at that time.19Myriam Fougère, dir., Lesbiana: A Parallel Revolution (Women Make Movies, 2012).

The creation of a utopian, liberated space, both actual and imagined, was a key part of early women's liberation. It is why the arts were so enmeshed with political activism; why "consciousness-raising" moved from physical gatherings to novels; why women's press collectives were seen as political activism. Physical and imaginative space were mutually interdependent, and a compelling imagined space might end up having more impact than a physical space.

Many writers in the southern lesbian feminist archive were invested in communes and collectives. Bertha Harris went with a group of lesbian friends (including anthropologist Esther Newton and her then-lover Louise Fishman, the painter) to an upstate New York property owned by Jill Johnston,20Esther Newton, Margaret Mead Made Me Gay: Person Essays, Public Ideas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 277n6. which served as a weekend getaway and part-time retreat that Harris would later memorialize in Lover. Blanche McCrary Boyd joined a commune in Vermont (not an exclusively lesbian commune, though she transforms it into one in Terminal Velocity); Rita Mae Brown was part of a women's collective, the Furies, in Washington, D.C., and when she eventually moved to Virginia (after the sale of Rubyfruit Jungle to Bantam Books) she didn't establish a commune, but she did buy land.

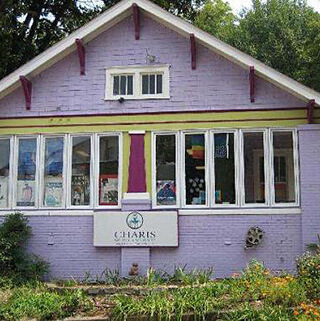

In Rebels, Rubyfruits, and Rhinestones, James T. Sears describes a seamless transition of southern queers from their small southern towns to New York City and back to intentional communities in the South—a fluid circulation that negated neither urban gay communities nor southern identities.21James T. Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001). The Pagoda community in St. Augustine, Florida was one of the most famous,22For more information, see Lin Daniels, "Pagoda, Temple of Love: Practice Ground for the Matriarchy," 1977, http://kongress-matriarchatspolitik.ch/upload/Lin-Daniels.pdf. but many smaller ones thrived under the radar across the South. Dorothy Allison belonged to a women's collective in Tallahassee, Florida. Catherine Nicholson lived in a collective in Charlotte, North Carolina but was kicked out for her intergenerational romance with Harriet Desmoines; photographs of the Sinister Wisdom group, taken at Nicholson's house on Country Club Drive (with many of the women topless), suggest a faux commune had formed there. And Catherine Ennis, who was so cautious that she wouldn't do readings of her lesbian novels too close to her hometown, appeared in the Ponchatoula Times in the mid-1980s with her "artisans" collective; the photograph suggests a lesbian commune flying under the radar.23"Copper Fountains Bring Ponchatoula Artisans Fame," Ponchatoula Times, July 31, 1986, http://ptl.stparchive.com/pageimage.php?paper=PTL&year=1986&month=7&day=31&page =1&mode=F&base=PTL07311986P01&title=The%20Ponchatoula%20Times. In smaller communities this sort of caution wasn't uncommon. Other communes—usually those in urban centers or college towns in the South—were more open and combative, though often no more visible. The Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA), which operated for two decades in the largest urban center in the South and hosted a number of lesbian writers, including southern lesbian feminist writers, was largely unknown in Atlanta proper. The Feminary collective in Durham, North Carolina was well known within lesbian feminist circles but fairly anonymous inside the Research Triangle. More recent communes include one in Alabama and Camp Sister Spirit in Mississippi.24A 2009 New York Times article discusses the Alabama community—see Sarah Kershaw, "My Sister's Keeper," New York Times, January 30, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02 /01/fashion/01womyn.html. For more on Camp Sister Spirit, see "Controversial Camp Sister Spirit Celebrates 10 Years," WLOX News, September 22, 2003, http://www.wlox.com/story/1451559/controversial-camp-sister-spirit-celebrates-10-years/.

Despite their many differences in locations, visibility, and intentions, all these communes and collectives served an important function in the archive of southern lesbian feminism. Southern lesbian feminists were deeply invested in the spaces and places of the South. Whether they stayed in the South or fled to New York or San Francisco, they engaged imaginatively and combatively in the remaking of southern place to create a South they did not have to leave. Southern lesbian feminists—white, Latina, and African American—reconsidered their own "sense of place" in regard to their sexual identities and regional inheritance.

Southern lesbian feminist writers reinvent southern space as an imagined kingdom of racial impurities, sexual perversity, and political radicalism. In their imaginary sites of southern space, they include utopian imaginings, communes and collectives, and queer contact zones within the larger communities.

About the Author

Jaime Harker is professor of English and the director of the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies at the University of Mississippi. Her research centers on popular American women writers of the interwar period, Cold War gay literature, and women's liberation and gay liberation literature. Prior to writing the book from which this essay is excerpted, she has written two other monographs: America the Middlebrow: Women's Novels, Progressivism, and Middlebrow Authorship Between the Wars (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007) and Middlebrow Queer: Christopher Isherwood in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Recommended Resources

Text

Allison, Dorothy. Skin: Talking about Sex, Class & Literature. Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1994.

Beemyn, Brett, ed. Creating a Place for Ourselves: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Community Histories. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Boyd, Blanche McCrary. Terminal Velocity. New York: Vintage Books, 1998.

Griffin, Connie, ed. Crooked Letter i: Coming Out in the South. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2016.

Howard, John. Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Black. Queer. Southern. Women.: An Oral History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Sears, James T. Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Web

Atwell, Elizabeth. "Feminary: A Feminist Journal for the South Emphasizing the Lesbian Vision." Outhistory.org. Accessed April 15, 2019. http://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/nc-lgbt/periodicals/Feminary.

Gieseking, Jen Jack. "Gender, Sexuality, and Space Reading List." Jgieseking.org. Accessed April 13, 2019. http://jgieseking.org/current-projects/gender-sexuality-space-reading-list/.

———. "LGBTQ Spaces and Places." LGBTQ Heritage Initiative Theme Study. National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Last modified October 10, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/articles/lgbtqtheme-places.htm.

Kershaw, Sarah. "My Sister's Keeper." New York Times, January 30, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/01/fashion/01womyn.html.

Massey, Doreen. "Space and Power are Intimately Related: Interview with Doreen Massey." Interview by Shared Spaces. Public Space, Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, July 26, 2012. https://www.publicspace.org/multimedia/-/post/space-and-power-are-intimately-related.

Reeves, Jay. "Project Documents Hidden History of LGBTQ Life in the South." AP News, August 20, 2018. https://apnews.com/ce5f60c4f0a64f8c9f489700ea21a9a4.

Similar Publications

| 1. | For more see, Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies' Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008) and Micki McElya, Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). |

|---|---|

| 2. | John Howard, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 14. |

| 3. | Howard, Men Like That, 15. |

| 4. | Scott Herring, Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 9. |

| 5. | Jen Jack Giesking, "A Queer Geographer's Life as an Introduction to Queer Theory, Space, and Time," in Queer Geographies: Beirut, Tijuana, Copenhagen, eds. Lasse Lau, Mirene Arsanios, Felipe Zuniga-Gonzalez, Mathia Kryger, and Omar Mismar (Roskilde, Denmark: Museet for Samtidskunst, 2014), 14. |

| 6. | Gillian Rose, Nicky Gregson, Jo Foord, et al., Introduction to Feminist Geographies: Explorations in Diversity and Difference, ed. Women and Geography Study Group (Essex, UK: Longman, 1997), 9. |

| 7. | Rose et al., Introduction to Feminist Geographies, 9. |

| 8. | Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage Publications, 2005), 140–141. |

| 9. | Massey, For Space, 13. |

| 10. | Giesking, "A Queer Geographer's Life," 15. |

| 11. | Giesking, 15. |

| 12. | Greta Rensenbrink, "Parthenogenesis and Lesbian Separatism: Regenerating Women's Community through Virgin Birth in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s," Journal of the History of Sexuality 19, no. 2 (May 2010): 291. |

| 13. | David Bell and Gill Valentine, "Introduction: Orientations," in Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities, eds. David Bell and Gill Valentine (New York: Routledge, 1995), 8. |

| 14. | Sine Anahita, "Nestled into Niches: Prefigurative Communities on Lesbian Land," Journal of Homosexuality 56, no. 6 (August/September 2009): 724. |

| 15. | Rose Norman, Merril Mushroom, and Kate Ellison, "Notes for a Special Issue, Landykes of the South: Women's Land Groups and Lesbian Communities in the South," Sinister Wisdom 98 (Fall 2015): 8. |

| 16. | Norman et al., "Notes for a Special Issue," 5. |

| 17. | Dee Mosbacher, dir., Radical Harmonies: Woodstock Meets Women's Liberation in a Film about a Movement that Exploded the Gender Barriers in Music (Wolfe Video, 2004). |

| 18. | Rensenbrink, "Parthenogenesis and Lesbian Separatism," 292. |

| 19. | Myriam Fougère, dir., Lesbiana: A Parallel Revolution (Women Make Movies, 2012). |

| 20. | Esther Newton, Margaret Mead Made Me Gay: Person Essays, Public Ideas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 277n6. |

| 21. | James T. Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001). |

| 22. | For more information, see Lin Daniels, "Pagoda, Temple of Love: Practice Ground for the Matriarchy," 1977, http://kongress-matriarchatspolitik.ch/upload/Lin-Daniels.pdf. |

| 23. | "Copper Fountains Bring Ponchatoula Artisans Fame," Ponchatoula Times, July 31, 1986, http://ptl.stparchive.com/pageimage.php?paper=PTL&year=1986&month=7&day=31&page =1&mode=F&base=PTL07311986P01&title=The%20Ponchatoula%20Times. |

| 24. | A 2009 New York Times article discusses the Alabama community—see Sarah Kershaw, "My Sister's Keeper," New York Times, January 30, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02 /01/fashion/01womyn.html. For more on Camp Sister Spirit, see "Controversial Camp Sister Spirit Celebrates 10 Years," WLOX News, September 22, 2003, http://www.wlox.com/story/1451559/controversial-camp-sister-spirit-celebrates-10-years/. |