Overview

Brian Riedel explores the role of cruising in queer territorialization and place claiming in Houston, Texas, in the twentieth century. Juxtaposing digital maps of queer businesses with an archive of cruising narratives, Riedel shows that while mapping business data offers one visualization of queer territory in Houston, archival narratives of cruising suggest that cruising areas have more complex relationships to commercialized spaces—sometimes directly connected, at other times peripheral and symbiotic, and at others seemingly divorced. These narratives, in parallel with the maps, point to multiple, contested queer territories spread across Houston in memory and practice.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

Introduction

What role does cruising play in marking specific areas of the urban landscape as "queer territory"?1For the purposes of this essay, I use the word "queer" primarily in its capacity as a contemporary umbrella term intended to include the panoply of non-normative sexual and gender identities concatenated in familiar and unpronounceable acronyms like LGBT, LGBTQ+, and LGBTQQIAA. To be sure, other speakers and thinkers deploy "queer" with additional senses—an historical term of derision, a specific identity, a verb. The word can summon all these thoughts and more, regardless of authorial intention; indeed, it can carry whatever freight we readers bring to it. When I intend these specific meanings in this text, I will do my best to flag them. In general, I argue our politics and communities benefit most when we embrace the untidy polysemy of "queer" and explore the openings it provides. Since the 1970s, social scientists have proposed and critiqued various models of queer territorialization. Martin Levine used spot maps of bars and cruising grounds to substantiate a "gay ghetto"; Jen Jack Gieseking analyzed individuals' "mental maps" of queer space; Amin Ghaziani critiqued the enclave theory of "gayborhoods" in favor of what he terms "cultural archipelagos."2Martin Levine, "Gay Ghetto," in Gay Men: The Sociology of Male Homosexuality, ed. Martin Levine (New York: Harper and Row, 1979), 196–218; Jen Jack Gieseking, "Queering the Meaning of 'Neighbourhood': Reinterpreting the Lesbian-Queer Experience of Park Slope, Brooklyn, 1983–2008," in Queer Presences and Absences, eds. Yvette Taylor and Michelle Addison (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 178–200; Amin Ghaziani, There Goes the Gayborhood? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015; Amin Ghaziani, "Cultural Archipelagos: New Directions in the Study of Sexuality and Space," City & Community 18, no. 1 (2019): 4–22. All these models of queer territory posit collective understandings of place that transcend the social boundaries of queer identity groups.

All three authors also reference cruising, but offer little detail about how cruising works in their models. Using the city of Houston as an example, this essay attends to cruising as an underdeveloped aspect of those models. As Houston's Montrose neighborhood came to be identified as a "gayborhood" between 1960 and 1980, archival evidence shows that cruising narratives played a powerful role in that identification. At the same time, these narratives also show that queer territorialization in Houston was not a smooth process of collective place claiming and recognition. Rather, dissent and conflict over the practice of cruising in Houston shows queer place claiming to be fractured, contested, and structured in part through a politics of respectability inflected explicitly by class but curiously silent on race. Importantly, that fractured and contested structure is due in part to the converging efforts of a wide array of disparate agents: queer sex-seekers, Houston residents, local politicians, civic groups, queer organizations, national anti-pornography groups, and conservative political movements. These narratives also point to complicated relationships between cruising and other markers frequently used to define queer territory, specifically businesses serving a queer clientele.

Cruising: Practice and Concept

Cruising takes the art of the flâneur—passing time watching people, usually in public—and imbues it with the additional potential or explicit purpose of finding a sex partner. As Alex Espinoza has evocatively described, cruising can lead to sex in situ, whether in public locations like parks or semi-public locations like restrooms, but often leads to sex elsewhere in more private spaces.3Alex Espinoza, Cruising: An Intimate History of a Radical Pastime. Los Angeles, CA: Unnamed Press, 2019. It can also happen inside commercial establishments that charge a fee to access other clientele in a semi-private space, like bathhouses, video arcades, and adult book stores. Out of doors, cruising can happen both on foot and, after the popularization of the automobile, by car as well. Cruising is also associated strongly but not exclusively with gay men. In our information age, dating websites and hookup apps on mobile phones—Grindr, Scruff, Growlr, Boyahoy, Jack'd, and others—seem to remove much of the guesswork (but definitely not all the danger) from divining who might be nearby and looking for the same thing. Many men seeking men for sex today came of sexual age through these digital tools, leading writers like John Fielding to ask whether the prominence and distribution of cruising as a queer social practice has waned as a result.4"In the Age of Grindr, Cruising and Anonymous Sex Are Alive and Well," Vice, January 7, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/qbv5n3/cruising-in-the-age-of-grindr-828.

While this essay centers upon the importance of cruising in a particular place and a past era—Houston between 1960 and 1980—the rich scenes it describes should not be misconstrued to suggest that cruising is a thing of the past. Rather, contemporary popular culture, high art, literature, pornography, and vernacular speech continue to reproduce face-to-face cruising in public as part of a globally available gay sexual vocabulary and social practice. Espinoza's Cruising movingly shows the practice is not of a bygone era or one in which only certain (morally questionable) people engage. His book has received critical acclaim in part for its temporal and global scope—ancient Greece, England, Russia and Uganda receive specific attention—but also for his sensitivity both to disability and Latinx experience, as well as his assertion that cruising can offer contact across class and racial lines. That assertion echoes Samuel R. Delany's analysis of cruising in New York as a form of "contact" in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999).5John Birdsall, "Review: 'Cruising' maps the cultural history of L.A.'s hookup spots," Los Angeles Times, July 3, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/books/la-ca-jc-review-cruising-alex-espinoza-gay-history-20190703-story.htm. In short, cruising persists as a culturally relevant practice in the United States and elsewhere, one that often moves across social boundaries and identity categories.

Men seeking men for sex has never been the sole determinant of queer territory. For those who know how to read it however, both then and now, cruising marks public and semi-public spaces as at least temporarily queer(ed) territory. This marking is how cruising functions not only as a social practice but also as a concept. Through documenting the disparate networks of people who came to meet on Houston's cruising grounds—intentional sex-seekers, criminals exploiting stigmas attached to gay sex, ambivalent law enforcement officials, area denizens, and perhaps initially naïve passersby—I argue that the social distribution of knowledge about cruising illustrates that queer territories functioned in part because some who do not identify as "queer" also imagined those territories as connected to queer lives.

This distributed social knowledge is the kind of information that Levine described under "culture area," that Gieseking captured through "mental mapping," and that Ghaziani articulated through his concept of the "cultural archipelago." Although similar in emphasis, these theorists differ significantly in how they imagine the process of place claiming. Levine borrows four criteria from the sociologists Robert Park and Louis Wirth to assess the status of a "gay ghetto": institutional concentration, culture area, social isolation, and residential concentration. Levine mapped bars and cruising areas listed in Bob Damron's 1976 Address Book to illustrate institutional concentration, and conducted a literature review and "exploratory fieldwork" in those concentrated areas to assess the remaining three criteria.6Levine, "Gay Ghetto," 185. His "exploratory fieldwork" consisted of walking around neighborhoods observing gay life and talking with gay people, activities quite parallel to cruising itself. Particularly in his assessment of culture area, Levine describes a remarkably smooth process of place claiming. Within the culture area, "open displays of affection [between men] rarely evoke sanctions; for the most part, people either accept or ignore them. Even police patrols through these spaces pay little attention to such behavior. . . . In other places, such behavior quickly elicits harsh sanctions."7Levine, "Gay Ghetto," 204.

By contrast, Gieseking and Ghaziani attend more closely to a multiplicity of perspectives, change over time, and conflict in social descriptions of place. Gieseking defines mental mapping as "the representation of an individual or group's cognitive map" of a specific place.8Jack Jen Gieseking, "Where We Go From Here: The Mental Sketch Mapping Method and Its Analytic Components," Qualitative Inquiry 19, no. 9 (2013): 712. While most of Gieseking's work is credited as "Jen Jack," this article flips those names. In visualizing both multiple individuals' and group perceptions' of a place, Gieseking finds that mental sketch mapping can "afford participants and researchers alike a way to share and see more multidimensional stories of themselves and their experiences through the lens of space and place."9Gieseking, "Where We Go From Here," 723. For his part, Ghaziani observes that "new residential and leisure queer spaces are forming across the city, and beyond its borders as well." That multiplicity of spaces grounds his proposal "that we redirect the study of sexuality and space away from our preexisting assumptions of spatial singularity—evinced by a steady stream of publications about individual gay districts—toward a cultural archipelagos model of spatial plurality."

Although Levine's work gives an important foundation, the history of cruising in Houston more closely exemplifies the social dynamics Gieseking and Ghaziani describe. During the twenty-year span centered on the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York, cruising narratives in Houston exhibit a multiplicity of opinions about a multiplicity of spaces, even as public awareness of the Montrose neighborhood as "gay" solidified both locally and nationally. This essay analyzes mainstream and queer sources of the time to construct and juxtapose two datasets: a GIS-enabled mapping of historical queer business data and an archive of narratives of cruising. While the business data offer one visualization of queer territory in Houston, narratives of cruising exceed the capacities of that mapping. Cruising areas have complex relationships to commercialized spaces—sometimes directly connected, at other times peripheral and symbiotic, and at others seemingly divorced. At the same time, these seven cruising narratives I feature here illustrate that efforts to regulate cruising converge from multiple, conflicting sources, including queer newspapers and community10Like "queer," "community" is also a freighted word. While I use it in this essay as a shorthand, I encourage readers to be cautious about the degree of coherence, agreement, organization, and unity they take it to convey. organizations with a range of stances toward queer life.

Mapping Queer Houston

I first came to live in Houston in 1997. When I arrived, the Montrose neighborhood was the epicenter of a thriving queer community. It was home to the largest concentration of Houston LGBT bars as well as many non-profit organizations, from the Montrose Counseling Center to Pride Houston. There were two queer bookstores, a free monthly magazine, and several free weekly papers. Soon, I was working for one of those papers, distributing copies all over the city. That labor helped me question and reimagine my first assumptions about the distribution of queer life in Houston. In this car-addicted place, queer bars and businesses were not just in the trendy Montrose neighborhood, but in far-flung suburban strip malls as well. Even so, Montrose remained the symbolic core.

That was not always the case. In 1911, J. W. Link and his business associates platted and marketed the Montrose Addition as an upscale suburb for middle- and upper-class Houstonians to escape the dirt and heat of the urban core. The Link Mansion built at the corner of Montrose and Alabama streets to advertise the new neighborhood was for some time the most expensive private home in Houston. To understand better how Montrose shifted from that elite suburb to a "gayborhood," I began a project in 2014 inspired by Levine's spot maps. I built a database of over 400 historical queer businesses11The definition of "queer business" here deserves some nuance. The database captures businesses explicitly marketed to a queer clientele. Historical queer advertising usually depicts that clientele as gay men and lesbians, often but not always as separate populations rather than a single market. Businesses were included in the database if they advertised in a Houston-based publication aimed at a queer readership or appeared in a national directory such as Damron's Address Book. This is not to say that queer community owned each business or that queer community was the only clientele. This nuance also matters when thinking about the relationship of cruising to commercial space, whether or not that commercial space can be thought of as queer. identified in Houston's historic queer publications like The Albatross, The Nuntius, and This Week in Texas, and supplemented those publications with other historical sources. I cross-referenced these locations through Houston's city directories to confirm the length of time each business was in operation at every street address given for it. Some bars relocated, for example, often after a fire. Using ArcGIS, I visualized that database from 1941 to 2015 on a contemporary base map of Houston to help orient present day viewers. Finally, I sequenced the 74 maps into a short animation.[2] 12Brian Riedel, "CSWGS Where is LGBTQ Houston?" YouTube video, 3:15, March 15, 2018, accessed December 31, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=baSgYQtkTSI&feature=youtu.be&ab_channel=RiceUniversity. This animation was also displayed at Houston's Heritage Society in 2015 as part of the six month installation "Throughout: Houston's GLBT History."

That animation suggests several phases to describe Houston's queer geography and history, phases that can also be visualized through a graph of businesses over time (see graph below). From 1941 to 1955, most businesses catering to queer community (though often not exclusively) operated in downtown, present-day Midtown, or the Rice Village area. The first location in Montrose was Art Wren's, a diner that ran from 1956 to 1971. Art Wren's also gained a national profile; it is one of nine "interesting" Houston locations listed in a 1962 souvenir program of the League for Civil Education's drag fundraiser in San Francisco, "Michelle International."13"Michelle International," League for Civil Education, accessed December 31, 2019, https://www.queermusicheritage.com/fem-michelle.html. Of the nine locations listed for Houston, I have been able to confirm locations for six. Beyond those six, I can confirm an additional seven locations not included in the souvenir program. That Art Wren's is among those six speaks further to the strength of its reputation. Here, "interesting" served as code for "gay"; the words "gay" and "homosexual" never appear in the League's program, even though the drag event raised money to help those arrested in raids on gay bars. By 1969, Houston's queer center of gravity was clearly shifting toward Montrose, but Midtown and downtown were still quite active. By the 1980s, the intersection of Westheimer Street and Montrose Boulevard was the center of queer life in Houston, and new bars and businesses began opening further west and into suburban areas. Even as the geographic distribution of queer spaces widened, the total number of locations peaked at 94 in 1982. During the 1980s, Houston endured the double impact of HIV/AIDS and the long economic fallout of the 1981 oil bust. The number of queer businesses began to stabilize at around 60 in 1991, but would begin dropping again at the turn of the twenty-first century. Montrose remained the dominant center as that number continued to taper. In 2015, just 31 businesses were operating, fewer than Houston had at the time of the Stonewall Riots.

Helpful as it is for visualizing change in queer Houston over time, this mapping project has significant limitations for the kinds of queer community it can be assumed to depict. Just at the level of "queer businesses," a mafia-owned bar with a partially queer clientele in the 1950s is not exactly the same kind of queer business as a lesbian-owned bar in the 1980s that hires a security firm to watch the parking lot.14See "Kindred Spirits," Houston LGBT History, accessed October 1, 2020, http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/misc-kindred.html. While such a 1950s bar could be any of those Carl Wittman laments in his "Gay Manifesto," the 1980's bar I mention here is quite specific. Marion E. Coleman started Kindred Spirits in Houston as an answer to many lesbians' problems with the bar options then available. She also hired a security firm to guard the parking lot and screen customers. Also, attending only to bars and businesses can skew our perception of queer space along class-inflected lines; professional middle-class and upper-class lesbians and gays eschewed the bar scene as dangerous for some time, even as recently as the 1990s.15See the letter writer to ONE below. In Houston, that pattern structured the Dianas, an almost exclusively white, upper-middle-class social organization of mostly gay men that originated in 1953 as an Academy Awards watch party in a private home.16"History of the Diana Foundation," Diana Foundation, accessed December 31, 2019, https://thedianafoundation.org/page/history-of-the-diana-foundation. That same pattern of discretion also influenced the creation of the Executive and Professional Association of Houston, founded in 1978.17"The Executive and Professional Association of Houston," EPAH, accessed December 31, 2019, https://www.epah.org/. In the more than 300 oral histories gathered through the Old Lesbian Oral Herstory Project, many lesbians—particularly those in middle-class professions like nursing and teaching—preferred softball and house parties to bars as ways to meet other women.18"The Old Lesbian Oral Herstory Project," OLOHP, accessed December 31, 2019, https://olohp.org/index.html. OLOHP owes a great deal to Arden Eversmeyer who trained women to collect oral histories across the United States. I am also indebted to an anonymous reviewer for bringing my attention to The New Orleans Dyke Bar History Project, accessed October 1, 2020, http://www.lastcallnola.org/. Those oral histories document a different perspective: some lesbians in 1970s and 1980s New Orleans preferred to meet each other in bars. See also John Howard's edited volume Carryin' On in the Lesbian and Gay South (New York: NYU Press, 1997). Mapping bar locations sourced in a mostly white-oriented gay press also elides Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color, along with their specific networks and practices.19For example, see see E. Patrick Johnson, Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South, (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2011) and Black. Queer. Southern. Women. (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

Beyond these limitations, the academic literature on queer territory also suggests the animation should account for the role of cruising as a place-claiming practice. Levine specifies cruising as a form of "institutional concentration" in his model of the gay ghetto, and even symbolizes cruising areas on his maps.20Levine, "Gay Ghetto," 1979. Levine also discusses cruising in chapter 4 of Gay Macho (New York: NYU Press, 1998). However, they appear as static present entities; he does not inquire into their pasts or their futures. Gieseking also positions cruising as one element in the creation of queer territory21Jen Jack Gieseking, "A Queer Geographer's Life as an Introduction to Queer Theory, Space, and Time," in Queer Geographies: Beirut, Tijuana, Copenhagen, ed. Lasse Lau et al. (Roskilde: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2013), 4–21. but takes care elsewhere to mark the limitations of both cruising and any emphasis on territory for the analysis of women's communities.22Gieseking, "Queering the Meaning of 'Neighbourhood,'" 2013. Ghaziani's There Goes the Gayborhood? briefly mentions cruising, framing it as an activity that could occur in any number of venues in the urban landscape.23Ghaziani, Gayborhood, 13. Ghaziani redeploys that same formulation of cruising in a more recent essay while arguing for "a cultural archipelagos model of spatial plurality" as an antidote to "enclave thinking." He argues that "the spatial expressions of sexuality are becoming more diverse and plural."24Ghaziani, "Cultural Archipelagos," 7. Though my mapping project did not visualize cruising areas, the research behind it did surface many narratives of cruising. Analyzing these cruising narratives in parallel with the mapping project, I argue that together they offer strong evidence to support Ghaziani's archipelagic model of queer territorialization in Houston at various moments across the twentieth century. Rather than any single enclave as figured in the footprint of Montrose, for example, these seven cruising narratives point to multiple, contested queer territories spread across Houston in memory and practice.

1930s: "Window Shopping"

The Houston queer press archive offers glimpses of cruising practices and mental maps that pre-date the temporal frame of my mapping project (1941–2015). In a 1988 article from the Montrose Voice,25"Montrose Voice," University of Houston Digital Libraries, Houston Texas, accessed October 1, 2020, https://digital.lib.uh.edu/collection/montrose. The Montrose Voice was published in Houston from 1980 to 1991. For readers unfamiliar with Houston's queer press history, I strongly recommend browsing the JD Doyle Archives, accessed October 1, 2020, http://www.jddoylearchives.org/. Richard Van Allen relates stories from men who lived in Houston before World War II, and recounts a queer urban geography through their eyes:

"The 'gay circuit'—they didn't know the word 'gay'—was downtown Houston, between Franklin and McKinney and Main Street east to San Jacinto. You could not tell a queer or a fag (the words they used then) from the straight, which was the way the gays wanted it, being fearful for their lives and jobs."26Richard Van Allen, "Houston's Gay Thirties," Montrose Voice, no. 410, September 2, 1988: 9. https://digital.lib.uh.edu/collection/montrose/item/8166/show/8130. This article has echoed in Houston media since then. See also William Michael Smith, "Looking Back at Some of the Hurdles Houston's Gay Community Had to Overcome (Part 1)," June 20, 2014, http://www.houstonpress.com/news/looking-back-at-some-of-the-hurdles-houstons-gay-community-had-to-overcome-part-i-6736836; "Houston's Earliest Gay scenes (Part 2)," Houston Press, June 23, 2014, http://www.houstonpress.com/news/houstons-earliest-gay-scenes-part-2-6748546; "'The Homosexual Playground of the South' (Part 3)," June 24, 2014, http://www.houstonpress.com/news/the-homosexual-playground-of-the-south-part-3-6737870.

Aside from a few bars that, while not intentionally or exclusively gay, served as gathering spaces to those in the know—the Rathskeller, the Old Vienna, the Capitol Bar, Rex's27Sadly, Houston city directories from the 1930s and 1940s did not confirm the addresses and locations for the bars documented in this article, so they are not included on the map. It is tempting to assume they fall within the sixteen-block area described by Van Allen.—what then functioned as queer "territory" was out on the street in that sixteen-block rectangle. According to a man Van Allen calls Dan:

"Of course, we didn't know the word 'cruising' then. We called it 'window shopping' and just like now, you know who was gay and who wasn't without asking. You could feel it, whether they had a limp wrist or not. There was this post down in front of Levy's department store. It had mirrors on four sides, and queers would stop and comb their hair there. Oh, you could spot them. If we did want to trick, we could get a room at the Milby or the Texas State Hotel. More often we went home to our apartments."

Much as Ghaziani describes "the closet era" of "scattered gay places"28Ghaziani, Gayborhood, 12–13. Ghaziani credits the second phrase as Ann Forsyth. prior to World War II, Dan's recollection of imagined gay space is opportunistic rather than exclusive. The social ecosystem of commercial downtown spaces—semi-public bars, shop windows, mirrored posts, and semi-private hotel rooms—created opportunities for strangers to meet for sex while providing a degree of plausible, respectable deniability. Gay networks circulated in parallel with other networks, but at least in Van Allen's account, cruisers would often move across the city landscape to more private spaces after meeting in more public ones.

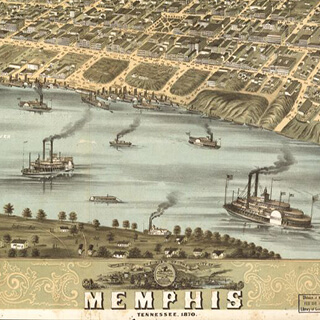

A striking way to situate this "window-shopping" area and the Montrose neighborhood in relation to the rest of 1930s Houston is to superimpose them on a now infamous Home Owners Loan Corporation map from the same era (see map above). The areas shaded red indicate the "hazardous" parts of town, where Black residents tended to live, and where the Home Owners Loan Corporation would not insure mortgage loans. The Montrose neighborhood, some two decades old at the time of this map and mostly shaded green, was the "best" type of neighborhood in which to live. Situated at the city's commercial core, the sixteen-block cruising area Van Allen's article described may well have provided opportunities for same-sex contact across both class and racial lines. And yet, Van Allen's narrators never mark race in their stories. The redlining map suggests at least one explanation for that absence, one that complicates any quick analogy to the kind of racial mixing found in Espinoza's memoir: the opportunistic use of public and semi-public spaces for cruising relied on an appearance of respectability that accounted for the persistence of racial as well as sexual lines in Jim Crow Houston.

1963: A Letter to ONE

From the 1940s through the early 1960s, however, the commercial spaces for queer community in Houston became less opportunistic and more intentional. Take for example a May 23, 1963 letter a Houstonian sent to the nationally distributed gay homophile magazine ONE,29ONE Magazine, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, 2018, https://one.usc.edu/archive-location/one-magazine. The magazine ONE was published in California from 1953 to 1967 and distributed nationally. It was the subject of the landmark 1958 US Supreme Court decision ruling that pro-homosexual writing was not of itself obscene. in which the writer offered his perspective on gay territory in the city:

Gay life in Houston seems relatively trouble-free as nearly as I can tell from my somewhat aloof perch (I don't patronize bars or attend parties or socialize much). A newly opened bar a few blocks distant is attracting great crowds on the week ends, with cars parked for blocks around, and always police watching especially toward closing time. The gay folks I meet seem delighted, and gloomily prophes[ize] that it is too good to last—I haven't heard of any trouble so far, though. Percentage-wise it seems to me this area has fully as many gay folk as any area in any of the larger cities in the North and West. Don't know of any other part of Houston where gay life is concentrated, though, except for a cheap theater downtown where the rough trade operates in amazing quantity and frankness—but could hardly call that gay life!30Craig M. Loftin ed., Letters to ONE: Gay and Lesbian Voices from the 1950s and 1960s (New York: SUNY Press, 2012), 114–5. To his credit, Loftin preserves the privacy of these letter writers by masking their precise addresses and substituting pseudonyms for their names.

While the writer's self-described "aloof" lifestyle may constrain our estimation of his version of events, the details he provided remain evocative. He spoke to a consciousness that "gay life" could be concentrated, perhaps even that it should be so organized. He also seemed to see himself as living in that concentrated part of town; he did not "know of any other part of Houston where gay life is concentrated" (emphasis mine). Still, he recognized a larger bar scene, though he did not attend it. (The map below provides a visualization of the bars and other businesses of which the writer might have been aware in 1963.)

The letter also captured the writer's sense that, for its size, queer Houston was not so out of step with the larger cities of the "North and West." New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and perhaps Los Angeles were his likely referents. Given the date of his letter and his description of a recently opened and wildly popular bar, it is also likely that his referent was Bob Eddy's Showboat, opened in 1962 on Tuam Street in present-day Midtown (labeled on the map above). For the writer, cruising was a primary if ambivalent index for whether "gay life" was "concentrated" in a particular location. The "cheap" theater he referenced is challenging to specify today given the lack of detail. I have yet to find an advertisement or mention of such a downtown theater in the queer press archive of the time; perhaps its rough trade reputation circulated only through hearsay. Whatever theater it was, the letter clearly shows that as late as 1963, this author's imagination of queer space in Houston was explicitly linked to present day downtown and Midtown. Montrose did not figure in his letter at all, even though Art Wren's had operated there for about seven years and had in 1962 already appeared in a local publication in California.

Another key index for the writer's imagination of gay life comes in the phrase "rough trade," a term still in use today. Then and now, the "rough" of "rough trade" signals men whose affect and physical appearance are both more working-class and more masculine—men who are not just "straight" acting and appearing, but who also might actually be more dangerous to approach, though that risk might itself be part of the thrill of approaching them. "Trade" signals that these men may, in fact, see themselves as straight, and that they could be only "dabbling" in same-sex activity. It also signals that these men might be seeking male clients in exchange for money, regardless of their or their client's sexual preferences. The writer to ONE gestured to this sexual ambiguity of "rough trade" when he divorced the downtown scene from what he called "gay life." At the same time, we might wonder how the writer himself was aware of the theater scene. He may have participated in it, at least enough to know just how abundant and frank the rough trade was. In any event, he does not disclose how he came to have that knowledge, even in the pages of a homophile magazine.

Importantly, the writer is also silent on the subject of race, a silence that suggests Jim Crow culture continued to texture both "gay life" and "rough trade" in the 1960s just as it had "window shopping" in the 1930s. At the same time, respectability politics are both explicit and implicit in his "aloof" observations. He marks the scene around the newly opened bar with cars "parked for blocks" and patrons who presumably have disposable income to spend at a bar, all signs pointing toward respectable middle-class status. By contrast, the "rough trade" scene at the "cheap" theater points to lowbrow entertainment and potentially sex work; their "amazing quantity and frankness" also signals their divergence from middle-class respectability.

1965: The "Phantoms" of Avondale

By 1965, however, Houston's locally produced queer press offers suggestive evidence that cruising areas had begun to shift into the Montrose neighborhood. One such piece ran in the first issue (1965) of the short-lived gay periodical, The Albatross.31"Who Are the 'Phantoms' of Avondale?" The Albatross, August 18, 1965, 1. All seven issues of The Albatross were published between 1965 and 1968 in Houston by Bob Eddy, the first owner of the Showboat bar.

The text is an intriguing window to the mise en scène of Montrose at the time. It appeared on the first page of The Albatross, marking the editors' sense of its importance with that placement. The text calls its readers to act, to report to the police crimes that the text assumes go unreported because the victims feared approaching the police. This attitude was reflected earlier in the ONE letter writer's description of police watching carefully as the bars closed. The Albatross' text specifies the location of attacks to Avondale, a subdivision adjacent to the Montrose Addition, centered on Avondale Street along the north side of Lower Westheimer. This neighborhood identity endures today in the Avondale Civic Association.32"Avondale," Avondale Association, accessed December 31, 2019, http://www.avondaleassociation.org/. The text also specifies a time: past midnight. It thus suggests a picture of who a typical victim might be: a male ("his personal safety" was at stake) walking or perhaps driving in a neighborhood after midnight, who might in fact be able to identify his assailant ("do not conceal the identity of these 'phantoms'") but feared to do so. Race remains stubbornly absent in this narrative, even as the text specifically marks class and criminality in the figure of "good people" who should not fear reporting to the police if they are attacked by the "unemployed, unwanted or purely incorrigible." While the article did not name the practice explicitly, cruising offers explanations for both that fear and why men might be walking or driving in the neighborhood late at night. Even if cruising was not the text's primary concern, the location it describes remains telling. Avondale offered a corridor between the 24-hour restaurant Art Wren's on Westheimer and the bars of Midtown to the east.

By 1965, three bars had also opened near the Avondale area: Numbers on California, the 900 Club on Lovett Boulevard, and the Round Table on Westheimer. Business owners and newspaper editors whose livelihoods depended on steady commerce likely also understood that the safety of their customers ("the good people of our community") was a prerequisite for their reliable patronage: all the more incentive for Bob Eddy—owner of Houston's Showboat and editor of The Albatross— to launch his paper with the "phantoms" as front-page news.

1970–1972: "Risky Crusing" and "The Heat"

While The Albatross' article was circumspect or perhaps even purposefully vague, five years later The Nuntius33"The Nuntius & Our Community," Houston LGBT History, accessed October 1, 2020, http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/nuntius.html. The Nuntius was published in Houston from 1970 to 1976. would explicitly center dangerous activities in the title of an article: "Risky Crusing, Don't" [sic].34"Risky Crusing, Don't," The Nuntius 1, no. 20 (August 1970): 12. http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/Assorted%20Pubs/Nuntius/nuntius-1-2-8-70.pdf. Interestingly, the nonstandard spelling of cruising as "crusing" is consistent in this article; this essay honors that spelling as an historical artifact. The article references areas from Memorial Park to Midtown and the dangers such places offered would-be pleasure seekers. It cheekily opens with a reminder that cruising could "furnish you with a free ride downtown, cost you money, embarrassment and perhaps a great deal of time away from home." The "free ride" at stake here was likely to a police station, but perhaps also to a hospital. The article closes more seriously with the tale of one man who ended up at the Texas Medical Center's Ben Taub General Hospital35Ben Taub General Hospital opened in 1963 in the Texas Medical Center and is named after the Jewish businessman and philanthropist, Ben Taub (1889–1982) who never married. after being stabbed multiple times. It ends with the question: "Is sex at this price worth it?" Despite the core message to avoid danger, the article's geographical details simultaneously functioned as a guidebook. The description of Montrose even plotted a list of specific streets (see map below for an illustration of the "round-robin"):

The round-robin at Lovett Boulevard, Roseland, Hawthorne, Stratford, California, Avondale—well, you know the area better than I. This is not risky but just dangerous as h—. There have been many, many crusy [sic] queens beaten, stabbed, robbed and almost killed from picking up tricks in this area. This bad news area is a definite "No-No."

Midtown received an equal measure of detail, including specific landmarks like "Sunnyland Furniture" at Main and Tuam (also illustrated in the map above).36Suniland Furniture was located at 2817 Main Street. See a discussion thread on the Houston Architecture Information Forum, accessed December 31, 2019, http://www.houstonarchitecture.com/haif/topic/26168-suniland-furniture-building-2817-main-st/. But it is not as if these locations were entirely accidental. By 1970, the Montrose "round-robin" encircled a collection of eight queer establishments, with Art Wren's at the center. In Midtown, the intersection of Main and Tuam was also quite close to a number of other venues catering to queer community. The mapping project documented three queer businesses that operated in the 2900 block of Main—The Surf Lounge and two Nuntius advertisers, The Midtown Lounge and the Mini-Park Theater. A block away on Tuam was the successor to the Showboat, La Caja (also a Nuntius advertiser). A few blocks further was the Gold Room, a bar whose majority Black clientele likely inspired the tag line for its advertisement in the same issue of The Nuntius: "Where the Dark & Light Meet."37Gold Room advertisement, The Nuntius 1, no. 2 (August 1970): 7. Cruising was certainly one reason why some queer people went to these parts of town, but it was not the only reason. Moreover, the concentration of queer businesses and the visibility of queer people on the street did not guarantee safety for queer people in these areas, whether that danger came from police, thieves, or tricks gone wrong.38I am grateful to a peer reviewer who suggested comparing crime rates in known cruising areas against crime rates elsewhere in Houston; that work remains a compelling future area for research.

Not all welcomed cruising in public. In early 1972, The Nuntius ran a short article, "Heat on the Circuit," several pages in that describes how "the Houston Police have been making every effort to curb the crusing [sic] in the areas of Lovett, Roseland, and Marshall Streets" (labeled as "The Circuit" in the map above).39"Heat on the Circuit," The Nuntius 3, no. 1 (January 1972): 15, http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/Assorted%20Pubs/Nuntius/nuntius-3-1-72-ocr.pdf. While the title and opening lines suggest the police (the "heat") should be the readers' main subject of concern, the article gestures toward the residents, "disturbed because of the heavy auto and pedestrian traffic during the late hours at night." The language to describe police efforts to "curb" cruising also suggests its readers might still have had an ambivalent relationship to the police. The article is also a form of soft control; it notified readers that officers were active in the cruising area and those cruising may wish to avoid encountering them. At the same time, the text describes the officers as "very cordial in the stopping and questioning of unauthorized persons frequenting this section." The police forces depicted here show at least a surface of courteous concern. Those with a legitimate (respectable) reason to frequent the area need not fear, but passers-through might still doubt who the final arbiters of that legitimacy would be. Presumably, the "unauthorized" could include both the cruising "hungry hannas" and criminals who prey on them, but we cannot assume that Montrose residents, their visitors, business owners, and bar customers themselves never cruised the streets where they lived, worked, and played. The Nuntius' depiction of the neighborhood shows several subtle but important shifts from the arrangement of queer community and police that marked the Albatross' item on the "'Phantoms' of Avondale." By 1972, queer pedestrians and drivers had become more visible, perhaps even emboldened in a post-Stonewall era, but were still at risk from both criminals and the police. Officers for their part had also become more vigilant. While queer people clearly remained subjects of potential police control, it appears that some were slightly more likely to see themselves as subjects of potential police protection, at least those queers who might be "authorized" to be walking or driving around Montrose as respectable residents, guests, or consumers.

These two articles from 1970 and 1972 also continue the trend of prior cruising narratives; neither mentions race in any explicit way. That absence of racial awareness reflects the dominance of white narratives in Houston's queer press at the time, but is also a curious elision given the rising visibility of Houston's Black queer life both locally and nationally. Beyond the Gold Room's advertisements in The Nuntius, the 1971 Damron Guide also coded the Gold Room as a very popular Black bar.40"Texas Bars, Baths, Etc.: From Bob Damron's Address Book 1971," Houston LGBT History, accessed October 1, 2020: 112, http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/houston68-71.html. More curious still is that The Nuntius ran multiple stories in 1971 about the Houston Gay Liberation Front picketing the Red Room (see map above for location) because it did not admit Black patrons. Even as activists were calling attention to the segregation of queer spaces in Houston, these two narratives of cruising could omit explicit discussion of race in a multiracial city.

1971: "Come and Browse, or Vice Versa"

Evidence of cruising also appears beyond documents generated specifically by and for queer communities. For example, Mayor Louie Welch's records41Louie Welch Collection, MSS 51, Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston, Texas. To be clear about my archival process and research methodology, I did not know at first that Welch's papers held citizens' complaints and police records that would matter to documenting histories of cruising or of Montrose. I came across these records quite by accident while looking to substantiate historian James Sears' assertion that Welch and gay bar-owner George Hauger knew each other. I have yet to find any evidence to prove or disprove the assertion. See James Thomas Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001): 55. preserve a host of documents reflecting political and social currents that converged to regulate cruising. Of particular interest for this essay are citizens' complaints urging local authorities to shut down sexually-oriented businesses like video arcades that would "degenerate" their neighborhoods. That records of these complaints survive today, specifically in Mayor Welch's archive, attests to the power of the social and political forces converging on cruising at the time. Some citizens believed the authorities could and should address the issue, while for their part, the Mayor and other local authorities evidently deemed cruising important enough to track and combat.

Though locally produced, these citizen complaints also stand in complex relationships with national anti-pornography campaigns, religious organizations, and conservative political movements, as analysts like Whitney Strub have argued.42Whitney Strub, Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011). In the case of Houston, some complaints to the Mayor were clearly driven by national mailing campaigns from organizations like Charles Keating's long-running Citizens for Decent Literature (CDL). Sometimes, these campaigns arrived in the mailboxes of people already deeply engaged, for whom CDL mailings were both affirmations of and ammunition for their existing efforts. When these local complaints target businesses serving a queer clientele, national anti-pornography campaigns enter into a network of converging effects in which battles to define urban space result in the arrests of both consumers of queer pornography and patrons using those video arcades to cruise in semi-private and presumably safer, commercial spaces.

The Police Complaints and Criminal Intelligence Report folders in Welch's papers reveal a chain of communications among the public, the Mayor's Office, and Chief of Police Herman Short. Those communications in turn generated specific police activities directly affecting queer lives. These records show not only that Chief Short's police department was to varying degrees responsive to Houstonians' complaints of perverse activity in their city, but also that it proactively engaged in intelligence gathering to infiltrate and map the social networks they saw as driving both perversion and social instability. The Criminal Intelligence reports track investigations into presumed weapons dealing by Black militants and meetings of leftist groups like the Socialist Workers Party43The Socialist Workers Party is a communist organization in the United States that traces its roots to 1928. In Houston, Texas, the SWP acted in coalition with other organizations on the left, including the Gay Liberation Front. and the Mexican American Youth Organization.44The Mexican American Youth Organization formed in San Antonio, Texas in 1967, and was regarded as a militant form of Chicano activism, especially relative to mainstream organizations like League of United Latin American Citizens. In Houston, MAYO had strong ties to the University of Houston campus, much like the Gay Liberation Front Houston. They also track claims of reciprocal arson among rival gay bar owners, intimidation tactics among national pornography distributors vying for control of the Houston market, and individual members of Houston's nascent Gay Liberation Front.45The Gay Liberation Front formed in New York shortly after the Stonewall riots of 1969, and quickly spread to Canada and the United Kingdom. Though it would frequently collaborate with other left organizations, it was short lived; other lesbian and gay organizations had largely supplanted it by the mid-1970s. In Houston, a branch of GLF formed in the Montrose neighborhood in September 1970 and organized a student group at the University of Houston.

To offer one example in which citizens' complaints of cruising converged with local police priorities and national anti-pornography campaigns, consider the correspondence between the office of the Mayor and a Montrose resident named R. L. Martinson.46Reproducing Martinson's real name is a considered choice. Primarily, he made himself a subject of public record by sustained communication with public officials. Also, unlike the letter writers in Craig Loftin's compilation, his actions at the time would not be interpreted as criminal, regardless of how we today might ethically evaluate those actions. Martinson took several opportunities to urge the city to prevent what he saw as the decay of Montrose. In a letter dated October 29, 1971,47Correspondence from R. L. Martinson to Mayor Louie Welch, 29 October 1971, MSS 51, Box 30, Folder 2, Louie Welch Collection. Martinson reminded the Mayor of a letter from some months before in which he had asked for help "to rid this and other neighborhoods of the filthy atmosphere of the adult book store and lewd movies." While his complaint might at first be taken as a generic complaint about pornography, he then specifically mentions the return of an adult bookstore ("Story Book") at the former location of the "Adult Library and Mini-Theater" at 1323 West Alabama, an advertiser in The Nuntius (though at the slightly different address of 1312 West Alabama; see map above). The location for both operations was only one block from Martinson's residence, today just north of St. Thomas University and west of the Annunciation Orthodox Church.

In an all too familiar rhetorical move foreshadowing Anita Bryant's 1977 "Save Our Children" campaign, Martinson focused on protecting "youngsters" from the "crowd of homosexuals and perverts who roam the neighborhood night and day." Whether or not Martinson's "roaming" is the same distinctively spelled "crusing" that The Nuntius warned its readers against, the situation apparently had been sustained for some time, as Martinson writes that he and his neighbors "have suffered enough in the past two years." Indeed, queer newspaper advertising indicates that the Adult Library first opened on Alabama in 1970.48The Houston City Directory intriguingly shows that, immediately prior, the location was occupied by "Miss Adorable Wigs." As a 24-hour venue advertising with the tag line "Come and Browse, or 'Vice-Versa,'" the Adult Library would indeed have attracted the kind of cruising traffic Martinson's "roaming" describes. The "Vice-Versa" also underscores how unlikely it was that customers came to the store just to browse. Presumably, most would browse the movies and the clientele on offer in the relative privacy of the store's video arcade. Perhaps they would select one or more sex partners—especially if the viewing booth they chose offered openings into other booths. In all likelihood, given the purpose of such arcades and the business's tagline, many would also come before they left, whether or not this occurred with a partner.

Martinson's letters also demonstrate his willingness to argue that the laws supported his position and would empower city authorities to act accordingly, though his own narrative is vague about precisely which laws might actually have done so. His October 1971 letter refers simply to "a new law which apparently went into effect September 1." Martinson clearly assumed this law somehow led to the closure of the Adult Library. More specifically, in another letter to the Mayor dated February 12, 1972,49Correspondence from R. L. Martinson to Mayor Louie Welch, 12 February 1972, MSS 51, Box 30, Folder 4, Louie Welch Collection. he writes that "sodomy charges" were at stake. At the time, Texas and most other states did indeed have sodomy laws on their books; in 1972, the Texas statute also included heterosexual non-reproductive acts but would be refined in 1973 to apply only to same-sex acts. However, there was no 1971 adjustment to the Texas penal code and the various sex crime laws described in its Chapter 21. As Texas House Speaker Gus Mutscher lamented of the 62nd session: "The much-discussed penal code reform was the second failure in 'must' legislation for the session. The state bar-recommended revision as presented in HB 419, proved to be controversial enough that sponsors said they would delay action another two years."50Gus Mutscher, "Accomplishments of the 62nd Legislature," 1972, 9. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://lrl.texas.gov/scanned/SessionOverviews/62_Accomplishments_1.pdf.

Beyond Martinson's legal theories and emotions about the reopening of the adult business, his October 1971 letter is remarkable for the social imagination driving his proposed solution: "Let's put these dens of pervertion [sic] in an isolated part of town, if we must have them, and not allow them in residential areas or shopping centers to tempt our youth."51Martinson to Mayor Welch, 29 October 1971. Despite witnessing two years of night and day homosexual presence, Martinson apparently could not imagine even in late 1971 that his neighborhood might already be that part of town. Perhaps his concern was that it would soon become so in the absence of his complaints.

The official acknowledgement of his October letter was swift, even if action was not. The Mayor's office marked it to forward to Chief Short, and sent a brief note to Martinson dated November 3, 1971.52Correspondence from the Office of Mayor Louie Welch to R. L. Martinson, 3 November 1971, MSS 51, Box 30, Folder 2, Louie Welch Collection. Despite that note's assurance that Chief Short would investigate and be in touch in the near future, it appears Martinson did not receive any of the promised updates. In his letter of February 12, 1972, his tone shifts toward impatience as he writes "once more" to "inquire what, if anything is being done about places such as the 'so called' Story Book at 1323 West Alabama."53Martinson to Mayor Welch, 12 February 1972. The invective of this letter targets "perverts" as it marks the frequent traffic of "characters" that circulate without "merchandise" at Story Book and the nearby Grass Hut, a venue other complaints mark as a "pot-parlor."54Correspondence from Coralie Anderson to Mayor Louie Welch, 28 April 1971, MSS 51, Box 29, Folder 12, Louie Welch Collection.

This February letter also surfaces a powerful converging effect: Martinson specifically refers to the January–February 1972 National Decency Reporter, a newsletter from Citizens for Decent Literature. Per Martinson, it reports "crackdowns And Convictions in Ohio, Nebraska, California, among others."55Martinson to Mayor Welch, 12 February 1972. Capitals and underscore in the original. Martinson's February letter received a similarly swift acknowledgement from the Mayor's office, dated February 17, once again noting that the complaint had been forwarded to Chief Short, but this time without any promises of further communication.56Correspondence from the Office of Mayor Louie Welch to R. L. Martinson, 17 February 1972, MSS 51, Box 30, Folder 4, Louie Welch Collection.

Although Martinson may not initially have received the degree of response he sought, action was eventually forthcoming. An internal police memo dated March 21, 197257Internal police memo from Sergeant T. R. Driskell to Lieutenant J. M. Albright, 21 March 1972, MSS 51, Box 30, Folder 4, Louie Welch Collection. went from Sergeant T. R. Driskell of the Vice Division up the chain of command via Lieutenant J. M. Albright to Chief Short, and from him to the Mayor, per a March 22 memo from Chief Short.58Internal memo from Police Chief Herman Short to Mayor Louie Welch, 22 March 1972, MSS 51, Box 30, Folder 4, Louie Welch Collection. The details of Driskell's memo illustrate how Houston police officers enacted the laws available to them as they understood them, while the chain of communication itself shows how closely the Mayor personally monitored police actions regarding the gay community. Driskell reported on the status of the state sales license, which cleared their check. Eight mini-movie machines were noted in the rear of the bookstore. Police surveillance further "revealed" that "homosexuals frequent this place,"59Driskell to Albright, 21 March 1972. although it is unclear precisely what techniques of surveillance and evidence substantiated that claim. It is clear, however, that on March 8, 1972, five patrons were arrested and charged with committing an "Indecent Act" under the then-operative Chapter 21 of the Texas Penal Code. "The manager was not arrested" as "he was not involved."60For those who have ever visited adult bookstores with video arcades, this exclusion might not surprise: a manager is usually up at the front, selling access to the movie and cruising area at the back. That said, I am also grateful for a reminder from an anonymous peer reviewer that "owners of bath houses, bars, or cinemas sometimes faced police crackdowns in other cities, even if they didn't engage in sex themselves." The impact of these converging effects on the Story Book was much broader than this one raid, however. Driskell notes that since July 29, 1971, "there has been a total of 27 arrests for various offenses" at this location. He also reports "we are in the process of trying to get an injunction through Civil Court and have this place closed."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, none of Martinson's letters or the police memos explicitly mention race.

1974: "Rough Trade"

While Houston-based and locally-distributed publications like The Albatross and The Nuntius range from elliptical descriptions of cruising to explicit cautionary tales, Ralph W. Davis's richly photographed December 1974 article about Houston in the nationally-distributed gay travel magazine Ciao! verges on the celebratory.61Ralph W. Davis. "Houston," Ciao!: the World of Gay Travel. December 1974, 10–13; available also via the JD Doyle Archives: http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/houston74.html. Ciao! was published out of New York City from 1973 through 1980. For more about the impact of Ciao!, see Lucas Hilderbrand, "A Suitcase Full of Vaseline, or Travels in the 1970s Gay World," Journal of the History of Sexuality 22, no. 3, (2013): 373–402. Indeed, "Cruise Areas" constitutes the first major subsection of his four-page article. He rehearses several areas mentioned in prior publications, beginning with the following bolded statement: "The main cruise area is Roseland to Hawthorn to Lovett to Stanford. Lovett and Stanford, and Lovett and Montrose are good corners to linger on at night." After directing readers first to a part of Montrose only five blocks from R. L. Martinson's home, Davis then helpfully notes, "Lovett and Stanford is a little darker than the latter, and some may prefer this for obvious reasons." Those "obvious reasons" would likely include the cover that darkness can provide for either a quick outdoor sex scene or an increased degree of camouflage and anonymity for the long term lingering sometimes required to pick up a trick worth taking elsewhere.

For Davis, not all cruising areas come equally recommended. He specifically evaluates them in terms of their "roughness," with all the gender and class markers animating the 1963 letter to ONE. The cruise area section of Davis' article continues the pattern of past cruising narratives and gives no guidance about the racial mix of men frequenting any specific area. However, the individual bar listings within the article do occasionally reference race and nationality. The clientele of the country/western Golden Spur "includes some tough Latins and blacks"; the Gold Room gets a nod toward the end of the article as "an old established black bar"; the Athens Grill and Bar on the Houston Ship Channel is recommended as "the place to go for Greek sailors who, when a little drunk, swing either way," a variation on the theme of rough trade. None of these three bars are close to any of the cruise areas Davis names, however.

Of those cruise areas, Davis found the roughest one to be the Midtown corner of Bell and Main that hosts Simpson's Dining Car, the Exile Lounge, and, though he does not mention it in writing, the Woodrow Hotel. One hint toward the hotel's role comes when Davis notes "[o]nce Simpson's was a 24-hour restaurant; now it closes at 1 a.m. to avoid serving some of the hustlers and roughs who settle almost all night on the corner of Main and Bell." On the last page of the article, he also describes the Exile as "probably the most recommended of the rough bars."

To complete the implication, an examination of two accompanying photographs of Simpson's Dining Car and the Exile Lounge reveals the Woodrow Hotel looming in the background of both, boldly advertising "75 Rooms," "75 Baths" and "Air Conditioning" on the wall facing Main Street. Industrious Ciao! readers would also have seen that the Damron Guides for 1971 and 1972 also list the Woodrow Hotel.

For hustlers cruising for a living, that single block provided a ready-to-hand circuit of the necessities: food, drink, a steady stream of potential customers, and a private room and bath when it came to business. For out-of-town and local johns looking for the right place to go, Ciao! pointed the way. At Main and Bell, cruising and commerce commingled in a much more intense and intentional way than the Story Book on Alabama.

1976: No Turns

Although the 1972 Nuntius article gives the impression that residents played a minor role—at most complaining to the police who then in turn engage the "unauthorized"—residents do become more organized and vocal agents over time. In September 1975, Virginia Galloway reported in Update Texas that residents had formed the Montrose Citizens Association (MCA).62Virginia Galloway, "Montrose Circuit," Update Texas, Sept 26–Oct 3, 1975, 2. While the organization's name suggests an expansive membership, details on it are scarce; organizational records point only to the name of a lawyer in Montrose: Richard L. Petronella.63Initial research about the MCA surfaced a helpful clue for further work, although the source for that clue is suspicious. See "Montrose Citizens Association Inc." Bizapedia, accessed December 31, 2019, http://www.bizapedia.com/tx/MONTROSE-CITIZENS-ASSOCIATION-INC.html. That website provided the following data: "Montrose Citizens Association Inc. is a Texas Corporation filed on September 2, 1975. The company's filing status is listed as Franchise Tax Involuntarily Ended and its File Number is 0036646201. The Registered Agent on file for this company is Richard L Petronella and is located at 815 Hawthorne, Houston, TX . The company's principal address is 815 Hawthorne St Richard Petronella, Houston, TX 77006-3901." The Association's remarkable strategy eerily echoed R. L. Martinson's proposal to Mayor Welch: relocate the Circuit. Galloway reported that "area gay organizations" collaborated with the MCA to pass out flyers at street corners in the Montrose Circuit on Friday and Saturday nights, informing potential cruisers of the "moving of the historic cruising area" from Montrose to a "non-residential, semi-isolated area nearer downtown" that would supposedly be "more conducive to cruising conditions, since the roads are better and there is good lighting." The flyer included a map of the new location and described the reasons for the move: "an effort to cooperate with neighborhood residents, who are finding the activity on the Circuit increasingly more difficult to live with because of the noise and traffic in the early morning hours." Supposedly, an impending police crackdown could be avoided if the cruisers were to voluntarily relocate. Galloway's reporting gestured quietly to the odd optimism of the scheme: "most were eager to hear of the new area, although actual response by moving is still slight." Houston cruisers in 1975 might have also remembered Ralph Davis' Ciao! article recommending a specific intersection in Montrose as darker than others. "Good lighting" was a curious way to pitch a new cruising ground to that market.

Such tactics aside, MCA's flyer campaign clearly required significant planning and volunteer effort, from designing and printing the flyers to the volunteer time of handing them out at multiple intersections on multiple nights. Although attorney Petronella is the sole name listed on the organization record, clearly he was not acting as a lone agent. Other community organizations were involved, perhaps even the Houston Police Department, especially if the new location for the Circuit would not also be subject to a police crackdown. Presumably, MCA also checked with the residents and business owners in the proposed new location to be sure cruising would not present a problem to them as well.

However, the Montrose Circuit's decade-long reputation as a cruising ground proved harder to break than the MCA campaign at first envisioned. Just a few months later, in March 1976, Mel Plummer (former owner of Update Texas) wrote a column for The Nuntius titled "Houston Cruise Circuit Closed," in which he argues that the flyer campaign failed because the roads at the new location could not handle the volume of car traffic, particularly during the peak weekend hours for the nearby Farmhouse, a three-story gay bar on Albany.64Mel Plummer, "Houston Cruise Circuit Closed," The Nuntius (March 1976): 3. http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/Assorted%20Pubs/Nuntius2/Nuntius%20SW-031276.pdf. This article repeats and extends a story of the same name run in the previous February issue. See The Nuntius (February 1976): 2. http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/Assorted%20Pubs/Nuntius2/Nuntius%20SW-020676.pdf. He places responsibility for this failing on MCA for choosing the relocation area on its own, rather than consulting first with "those involved with the Montrose circuit." Plummer's reporting also answered a curious gap in Galloway's account: he specified the gay organizations working with MCA as the Gay Political Caucus, the Metropolitan Community Church, and "other local organizations"—some of whom could also have offered expert guidance on the move. With the failure of the flyer campaign, Plummer reports that MCA escalated its efforts and barricaded the roads one night, purportedly with collaboration from the office of Mayor Fred Hofheinz. Plummer also casts doubt on that last claim, noting that the City had issued no permits and the police did not supervise the barricades. The barricades were not MCA's final option, however. The Association apparently described this new tactic as "their last stand before police harassment would begin to all those who frequented the infamous 'Montrose Circuit.'"65Ibid. The cordiality evoked in the 1972 The Nuntius article had evaporated.

MCA unleashed that final option on Wednesday, January 28, 1976.66Plummer's article reads "January 26," an apparent editing error. With the evident cooperation of the City of Houston, MCA installed signs prohibiting vehicles from making turns between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m. in the Montrose area. These no-turn signs restricted those cruising by car from circling legally through the side streets of the neighborhood, breaking the social pattern connecting cruisers on foot with cruisers in cars. Indeed, Plummer reports that the next night "Houston Police issued 43 traffic citations for illegal turns and five people were taken to jail. This has all but assured that the Montrose Circuit exists no more."67Ibid. Importantly, this "death" of the circuit also became mainstream news; Houston television stations picked up the story with what Plummer describes as "fair and unbiased reporting." To be sure, the crackdown on cruising in Montrose did not spell the death of cruising itself. Even as Plummer asserts that "most Gays have not found a new cruise route," he goes on to observe that "many are returning to the old cruise route before the days of Montrose. This was known to many as Suniland. The area consists of the streets Main, Tuam, Fannin, and Anita."68Ibid. Indeed, these are the very same streets The Nuntius readers might remember as too risky, as places where pleasure mingles with danger. One implication of this strange return is that the shifting of neighborhoods and cruising areas is not uniform, unidirectional, or irreversible.

It is also important for us today to recall that queer folk were not always victims but also sometimes the perpetrators of surveillance and violent crime in 1970s Houston. Such crimes may also have influenced those seeking to shut down or relocate cruising areas. Many of these crimes are all but forgotten. For example, The Nuntius ran a 1971 story about a teenage boy who was picked up by two men in downtown Houston and taken back to their residence in Montrose, "known to the most of us as 'the colony.'"69"Halloween Horror for 16 Year Old Boy," The Nuntius 2, no. 11 (November 1971): 1. http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/Assorted%20Pubs/Nuntius/nuntius-2-6-11-71.pdf. After what initially seemed to be an evening of drinks and movies, the boy "stated that he was knocked in the head by one of the men and tied up, beaten with a rubber hose and sexually assaulted by the pair."

Other crimes catapulted into the national consciousness. As Montrose residents and cruising men were engaged in their turf wars, Dean Arnold Corll had already begun what would come to be known as the Houston Mass Murders or the Candy Man Murders, in a gruesome nod to Corll's family business. Between 1970 and 1973, he and his accomplices are believed to have abducted, sexually tortured, and killed at least 28 teenage boys. While most of these boys had deep connections to or were taken in the Houston Heights area, the symbolic impact of the murders extended to all of queer Houston when the case was finally exposed in 1973 after one of Corll's accomplices murdered him. At the time, it was the worst serial murder case in United States history. The denouement of the Candy Man Murders played out the same year the American Psychological Association removed its classification of homosexuality as a mental illness in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

More intriguingly still, even as the Montrose Citizens' Association began its 1975 flyer campaign, the Houston Chronicle began reporting on a string of murders in Montrose, mostly of men, many of them graphically violent. Then the Chronicle's January 8, 1976 front page ran the headline "Homosexual Tells Police He Killed 3 Men Here." The first line of that story described the confessor, Joseph Standwick, as "an admitted homosexual."70"Homosexual Tells Police He Killed 3 Men Here" Houston Chronicle, January 8, 1976, Sec. 1, 1. Later coverage would add to that description: "admitted homosexual and male prostitute."71"Homosexual Suspect in 3 Slayings Questioned by Arson Investigators," Houston Chronicle, January 9, 1976, Sec. 1, 12. Such headlines and biased language deepen our understanding of why Plummer might specifically comment on the "fair and unbiased reporting" regarding the no-turn signs and cruising; just weeks before the no-turn signs went up, many Houstonians were imagining a murderous, gay prostitute in Montrose.

In that context, battles over whether gay men could or should claim Montrose as their cruising grounds have an understandable urgency, and not just for cruising men concerned about their own safety. As Ralph Davis wrote in Ciao! in 1974, "[t]he Mayor, in order to reduce growing tension arising between straights and gays, immediately advised bar owners that he would not interfere with business so long as their patrons weren't a public nuisance."72Davis, "Houston," 10. Given prior police raids on the Story Book and any number of other queer establishments, cruising men might mistrust such promises. Cruising in Montrose was steeped in emotions and conflicting interests: straight-gay tensions, business concerns, residents' long-standing noise and traffic complaints, and murderous headlines (none of which ever mentioned race as a motivating factor). To be clear: no extant records indicate that the Montrose Citizens Association explicitly or implicitly connected the Candy Man and Joseph Standwick to men cruising Montrose for sex. Still, the possibility of that connection may help explain how the MCA came to have the support of the Gay Political Caucus and the Metropolitan Community Church, both organizations invested in promoting the respectability of gay people.

Time would prove the MCA's no-turn signs to be a limited success, however. A decade later, a new no-turn sign campaign launched in Montrose, and the occasion spurred many to recall the limitations of the 1976 MCA effort. Connie Woods described the new campaign in the Montrose Voice: "signs went up . . . at four intersections between Alabama and Harold at the request of the Montrose Ltd. Homeowners Association, creating controversy among residents of the neighborhood who were unaware of such requests."73Connie Woods, "New 'No Turns' Street Signs Go Up," Montrose Voice, January 24, 1986, 11. She closed the article with a brief, neutral nod to the past: "Such traffic signs were first established in the Lovett Blvd. and Stanford area on the south side of Westheimer in the 1970s to discourage 'cruising.'" The pages of This Week in Texas (TWT) offered stronger commentary, quoting Montrose resident Charlie Miller: "Responsible people will note that these signs didn't stop cruising when they were erected on the east side of Montrose Blvd. . . . The circuit merely moved, and most likely will relocate again."74"Cruise Area Under Attack," This Week in Texas 11, no. 46. (January 31–Feb 6, 1986): 19–20. http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/TWT/1986/86-013186.compressed.pdf. TWT also quoted a 1985 letter from the Montrose Ltd. Homeowners Association to the city's Traffic and Engineering Department which made it clear they aimed to limit cruising:

The traffic begins increasing at dusk, is heaviest between 10 p.m. and 3 a.m. and continues until approximately dawn [… ] Most of the vehicles circle 10 or more times, but some have circled 50 or more times in one night. Depending on the day of the week, there are between 10 and 40 cars circling the block […] It's not unusual for four or more cars to be queued at each stop sign, waiting to turn the corner.

TWT readers were eager to share their thoughts in return. Bill Jackson wrote: "My apartment manager is, I believe, president of the homeowners association. I know, based on a conversation with him last fall, that they think anyone walking in the evening is soliciting, if not selling it."75Bill Jackson, "Letter to the Editor," This Week In Texas 11, no. 48 (February 14–20, 1986): 21. http://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/TWT/1986/86-021496.compressed.pdf. For his part, Don Buch argued that no-turn signs "demean and cheapen our Montrose properties and do not address the 'cruising' problem. It is in fact just a political tool for Houston police."76Don Buch, "Letter to the Editor," This Week In Texas 11, no. 48 (February 14–20, 1986): 23. As of this writing, some of the no-turn signs remain: two at the intersection of Marshall and Graustark, and nine along Roseland and Stanford streets. Despite consistent efforts from a variety of forces, the Montrose cruising circuits remained resilient.

Cruising Toward Theory

Taken together, these seven narratives of cruising do not describe an uncontested process of place claiming and recognition as Levine's model implies. Instead, they show territorialization through cruising to be temporally bound, conflicted, and structured in part through a politics of respectability explicitly linked to class concerns but uniformly silent on race. Considered alongside the brick-and-mortar locations of commerce and consumption that informed my earlier ArcGIS animation, these cruising narratives show that queer territories often operate on very different scales within and across multiple spaces. In these stories, the most typical scales of urban territory described are specific street corners, a few adjacent blocks, or occasional larger areas. Sometimes, but not always, these cruising grounds are connected to the commercial spaces privileged in the animation.

As the narratives attest, the practice of cruising has proponents and detractors. Tension over this practice in Houston largely stemmed from the range of agents involved and the variety of positions these agents took up on cruising. Over the years of analysis, the queer press promoted a number of stances on the behavior: discretely framed warnings, explicit admonitions that conveniently double as instruction manuals, and almost celebratory accounts of where specific kinds of action are to be found, ranked by dangers not limited to the threat of an encounter with the police. Queer and non-queer agents also intervened in a coalition to curb cruising. The Montrose Citizens Association had some degree of cooperation from the Gay Political Caucus and the Metropolitan Community Church. That alliance of respectable, community-oriented organizations built on years of residential complaints of noise and traffic even as Houstonians learned about a murderous gay prostitute in Montrose. The City of Houston directly engaged through policing, constituent messaging, and posting signage. Resilient sex-seekers responding to all of these agents seem to have found other places to pursue the chase, in part through cruising grounds remembered from other times. They had many alternatives available in collective, living memory, from cruising spots in downtown, Midtown, Montrose, Memorial Park, the Galleria, and beyond, to the adult bookstores and video arcades across the Houston landscape. At the same time, sex-seekers persisted in cruising areas like the Montrose Circuit, despite continuous efforts to displace them.

Beyond literal embodiments and emplacements, these narratives also illustrate that queer territories become so because both those who do identify as queer and those who do not identify as queer imagine them to be so. The full cast of characters holding these mental maps ranges widely in power, from unnamed neighborhood residents to the Mayor of Houston. These actors can be close to the field, like Richard L. Petronella and R. L. Martinson, and quite distant, like those reading Ralph Davis' article in the nationally circulated Ciao! magazine.77Benedict Anderson's arguments are particularly relevant here. See his Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso Books, 2006). Patterns of rough trade visible since the 1960s also suggest that some men—at least those who cruise other men for sex and do not identify as queer—also carry mental maps of queer territory, if only to avoid those places lest the label stick to them.