Overview

Combining materials from the Carolyn Weathers Collection in the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives and a 2015 interview with Weathers herself, Amanda Mixon sketches queer experience in early 1960s San Antonio, Texas. Mixon revisits gay bars, community formation, racial dynamics, policing practices, cultural representations, and military suasion to highlight the ongoing need for further exploration and study of historic gay spaces across Texas.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

Introduction

I remembered back to my coming-out days in San Antonio, Texas, in the early 1960s and realized that I had lived long enough and been out long enough to be historic.

— Carolyn Weathers

In October of 2015, I met with Carolyn Weathers in her condo in Long Beach, California. I had spent the past few weeks perusing her papers at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles mostly on a whim: she was one of the few individuals in the archive who hailed from the US South—Texas specifically—and as a queer southerner from Texas myself, I wondered what insights her collection might offer about LGBTQ+ experience in our home state. I never expected to come across photos of gay bars in pre-Stonewall San Antonio or a short story Weathers had written about her time in them. But as seasoned researchers already know and novices quickly learn, the archive is full of such surprises. Agreeing to an interview with me after an archivist put us in touch, Weathers and I spent a temperate, sunny southern California day together, lunching at a local café, walking the nearby boardwalk, and sitting down in her living room for a two-hour recorded interview. This essay combines information from that interview with the short story and photos from the Weathers Collection at ONE to develop a historical case study of LGBTQ+ experience in early 1960s San Antonio.

Structurally, I begin with a brief history of San Antonio to situate us in place before analyzing how Weathers narrativizes her experience in the city in her 1987 self-published short story "Cheers Everybody!" Next, I sketch four real historical bars that Weathers frequented: The Acme, Fernando's Hideaway, The Country, and Mary Ellen's Top Hat. I approach "Cheers" as a historical document that records how Weathers imaginatively used San Antonio to historicize and process her experience of the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. I develop the bar sketches primarily through my interview with Weathers—with occasional references to how she fictionalizes them in "Cheers"—and the archival photos from ONE. Together, these objects of analysis not only reveal the centrality of the gay bar to LGBTQ+ life in early 1960s San Antonio, but they also provide clues as to how the city's colonial and military history affected the formation of racialized gay space. In other words, although attentive to patron activities, demographics, and police encounters, the bar sketches investigate how these histories influenced the creation of gay space, which racialized subjects had access to gay space, and how that space was racialized or imbued with ideas about race as a consequence.1I follow Michael Omi and Howard Winant's definition of racialization: "the extension of racial meaning to a previously racially unclassified social relationship, social practice or group." Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2014), 111. Few studies—most of them unpublished dissertations and theses—about LGBTQ+ life in Texas during this period currently exist.2Besides the studies of San Antonio cited later in the essay, some relevant theses and dissertations of interest include: Kyle Edelbrock, "Taking it to the Streets: The History of Gay Pride Parades in Dallas, Texas, 1972–1986" (master's thesis, University of North Texas, 2015); Carl J. Stoneham, "How Prophecy Got Her Queer Back: (Re)discovering the Prophetic at the Rainbow Lounge, 40 Years and Eight Minutes Later" (master's thesis, Texas Christian University, 2010); and John D. Goins, "Confronting Itself: The AIDS Crisis and the LGBT Community in Houston" (PhD diss., University of Houston, 2014). As such, this essay is both a call to expand and further develop such research, as well as an example of how to make archival materials speak to the imbrication of LGBTQ+ identity and community formation within the colonial and racial formations that are central to the production of modernity.

To Historicize the Gay Bar

The origins of San Antonio's two nicknames—Alamo City and Military City, USA—lie in the city's history as a contested colonial space and as home to one of the largest concentrations of military bases in the United States. Founded by Spanish explorers and missionaries on the lands of the Payaya Indians in 1718, San Antonio de Béxar was capital of the Spanish and later Mexican colonial province called Tejas. After its 1821 independence from Spain, the newly established Mexican government began offering free land grants to Anglo-American settlers, who primarily took up residence in lands northeast of San Antonio. These Anglo settlers, who identified as Texians, and Hispanic settlers, who identified as Tejanos, fought against the Mexican Army led by President General Antonio López de Santa Anna during the Texas Revolution: the conflict from which the phrase "Remember the Alamo!" comes.3The actions of those fallen at the Alamo were glorified in Texas history and culture, and today, the Alamo commemorative monument and museum helps attract around 37 million annual visitors to San Antonio, whose tourism and hospitality industry generated an estimated 15.2 billion dollars in 2017.

Sparked by the Battle of Gonzales on October 2, 1835, the Texas Revolution resulted from decades of rising tensions between Tejas residents and the Mexican government, ranging from the Mexican state's abolishment of slavery in 1829 to its prohibition of new Anglo settlers in 1830.4The newly independent Mexican government began as the First Empire of Mexico headed by Agustín de Iturbide (1822–1823) before transitioning into a federal republic, with the Constitution of 1824 officially establishing the First Mexican Republic (Primera República Federal), known as the United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos). As the EUM sorted out its leadership and organizational structure, it failed to exert strong control and governance from Mexico City over the distant Tejas. Thus, the Mexican government's gradual steps towards abolishing slavery in 1829—which, in the eyes of many Anglo settlers, reneged on Iturbide's promise to let them practice chattel slavery in Tejas—and the prohibition of new Anglo settlers in the Law of April 6, 1830—which was precipitated by fears that the United States would annex Tejas and resulted in Mexican officials and troops being dispatched to enforce Mexican law in the province—encroached on the rights and privileges that settlers had grown accustomed to. The 1833 presidential election of Santa Anna only exacerbated these issues, as he threw out the Constitution of 1824, which allowed him to centralize control of the government by eradicating provincial or state governments, and also imprisoned Stephen F. Austin, the first empresario of Tejas and primary Texian representative, for a year. Less than a year later, on April 21, 1836, the Republic of Texas became official when Texians, Tejanos, and US volunteers defeated Santa Anna and his troops at the Battle of San Jacinto.5Randolph B. Campbell, Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987). But San Antonio remained a contested colonial space for decades after the Texas Revolution. By 1845, Mexico still did not officially recognize the Republic of Texas, and US Annexation that same year led to the Mexican–American War and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which forced Mexican cession of disputed Texas territory (see Figure 1) and its northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México (see Figure 2).6Campbell, Gone to Texas; Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas. As part of these war efforts, the US Army established its initial presence in San Antonio at Camp Almus, later consolidated as part of Fort Sam Houston in 1890 (the first permanent US military installation in the city). During World War I (1914–1918), the US War Department expanded the fort, with the additions of Camp Bullis, Camp Travis, and Camp Stanley, while laying the foundations for its fledgling aviation program. When the US Air Force gained autonomy after World War II (1939–1945) in 1948, the aviation infrastructure was divided into the Kelly Air Force Base, the Randolph Air Force Base, and the Lackland Air Force Base.7John Manguso, "Fort Sam Houston," Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 1, 2019, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbf43; Robert Wooster, "Military History," Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 1, 2019, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qzmtg. While Kelly AFB closed in 2001, the other two bases, along with Ft. Sam Houston, currently make up Joint Base San Antonio (JBSA), which contributes around 49 billion dollars annually to the city's local economy.8"2015 Military Economic Impact Study" (San Antonio, TX: Department of Government and Public Affairs, accessed July 1, 2021), https://www.sanantonio.gov/Portals/0/Files/OMA/EconImpact/2015SanAntonioMilitaryEconomicImpact.pdf?ver=2017-02-15-142835-893.

Although contemporary San Antonio's diversified economy (financial services, health care, energy, oil, and gas) attracts international and domestic job seekers, recently earning San Antonio the title of fastest growing city in the United States, population growth in recent decades pales in comparison to the boom between 1940 and 1960, when the city's population more than doubled, rising from 253,854 to 587,718, as a consequence of mass military mobilizations during WWII and a growing military job sector.9The United States Census Bureau designated San Antonio the fastest growing city in the United States in 2018: United States Census Bureau, "Census Bureau Reveals Fastest-Growing Large Cities," release number CB18-78, May 24, 2018, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/estimates-cities.html; "Texas Almanac: City Population History from 1850–2000," Texas Almanac, accessed April 5, 2019, https://texasalmanac.com/sites/default/files/images/CityPopHist%20web.pdf. These mobilizations, according to scholars such as John D'Emilio, Allan Bérubé, and George Chauncey, were part of a historical phenomenon that facilitated the formation of urban gay subcultures in US cities.10See Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (New York: Plume, 1991); George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994); and John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity" in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, edited by Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin (New York: Routledge, 1993), 467–476. "Millions of young men and women," D'Emilio notes, "whose sexual identities were just forming," were placed into "sex-segregated institutions," providing them opportunities to explore same-sex sexual desire.11D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," 472. Post-WWII suburbanization, which caused property prices in urban cores to plummet, making it easier to purchase real estate and open gay bars and nightclubs, as well as the founding of homophile civil rights organizations, such as the Mattachine Society (1950–1969) and the Daughters of Bilitis (1955–1995), whose respective publications, the Mattachine Review (1955–1967) and the Ladder (1956–1972), reached readers across the United States, enabled the growth of gay and lesbian neighborhoods, reading publics, and social networks.

In San Antonio specifically, gay and lesbian culture "grew dramatically in the 1950s and 1960s," writes Amy L. Stone, "and built upon a tradition of local nightclubs that had attracted female impersonators . . . in the 1930s and 1940s."12Amy L. Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy: Cold War Gay Visibility in San Antonio's Urban Festival," Journal of the History of Sexuality 25, no. 2 (2016): 300. Also, see Melissa Gohlke's blog post about these nightclubs and female impersonators: "San Antonio's Drag Culture of the 1930s and 40s," The Top Shelf, October 22, 2012, https://utsalibrariestopshelf.wordpress.com/2012/10/22/san-antonios-drag-culture/. According to Melissa Gohlke, "by the early 1950s, San Antonio led the five-state Fourth Army area" (Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico) "in off-limits places with fifty-three establishments."13Melissa Gohlke, "Off-Limits and Out of Bounds, World War II and San Antonio's Queer Community," The Top Shelf, February 25, 2013, https://utsalibrariestopshelf.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/off-limits-and-out-of-bounds-world-war-ii-and-san-antonios-queer-community/. Products of the 1941 May Act, which gave military police the authority to surveil and restrict access to places associated with prostitution and homosexuality, these "off-limits" lists, composed and released by military officials, conversely resulted in giving gay bars more publicity and patronage. "All a GI or WAC need[ed] to do [was] read the list," notes Gohlke, "and head out for a night of same-sex recreation."14Gohlke, "Off-Limits." While the military did not standardize anti-homosexual policies until the creation of the Department of Defense in 1949, each branch prohibited and prosecuted homosexuality through psychological screenings and forms of military discharge prior to and throughout WWII.15For further specification on these procedures, see Bérubé, Coming Out under Fire; Chauncey, Gay New York; and Margot Canaday's The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). If discovered in such venues, military personnel faced certain punishment, if not discharge.16Gohlke, "Off-Limits."

A native white Texan and self-identified lesbian born in 1941, Carolyn Weathers entered the San Antonio gay scene in her early twenties, at a time of increased scrutiny and persecution as a consequence of "antigay laws, the medicalization of homosexuality, nationwide panics about homosexuality as contagion, and anti-Communist organizing against homosexuality."17Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy," 299. Born in the central Texas town of Eastland to a middle-class Baptist family, Weathers spent her early childhood in Cleburne before moving to Brownfield in the Panhandle. The second daughter of an educator, Alida Nabors Weathers, and a Baptist preacher, Jones Weathers, Carolyn followed the geographical trajectory of her only sibling and older sister by two and a half years, Brenda, moving to Dallas, San Antonio, and ultimately Southern California. Kicked out of Texas Women's University in Denton for "lesbianism" in 1957 at the age of seventeen, Brenda introduced her sister to the queer worlds that she discovered in Dallas and San Antonio of the late fifties and early sixties. Carolyn came out in 1961 while living with Brenda in San Antonio. She later joined Brenda in Los Angeles, where they were initially drawn by the countercultural movement of the sixties, ultimately participating in feminist and LGBTQ+ activism during the seventies and eighties. As members of the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front (GLF-LA), Brenda founded the Alcoholism Center for Women (still in existence), and Carolyn was the first out lesbian on an Los Angeles television show, as well as a participant in the GLF raid of the American Psychiatric Association's 1970 convention in Los Angeles. Carolyn also contributed to the Women in Print Movement, creating Clothespin Fever Press in the mid-eighties with her partner at the time, Jenny Wrenn.18Weathers was featured on AM Los Angeles with Regis Philbin. In 1970, prior to the GLF raid of the APA's L.A. Convention, the GLF raided an APA convention in San Francisco. These raids were to protest the APA's classification of homosexuality as a mental illness. Having completed their post-secondary education in the late sixties, Brenda supported herself primarily through heading substance abuse centers and animal shelters, while Carolyn worked as a librarian for the Los Angeles Public Library. From the time Brenda and Carolyn came out throughout their years of activism, their parents remained supportive and maintained close relationships with each of them. Brenda passed from lung cancer in 2005, and Carolyn, a 2015 recipient of an LGBT Heritage Award by the City of Los Angeles, is currently retired in Long Beach.19Carolyn Weathers, interview by author, October 22, 2015, Long Beach, California, video recording. Biographical information is condensed from the interview.

Both my 2015 interview with Weathers and an analysis of how she narrativizes her experience in San Antonio in a 1987 self-published short story, "Cheers Everybody!" reveal how the city's colonial and military history affected the formation of racialized gay space as well as how Weathers imaginatively used San Antonio to historicize and process her personal experience of the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. When Carolyn wrote "Cheers Everybody!" in the mid-eighties, she wanted to document and comment on her lived experience. As she relates in the 1989 preface to the second edition of her collection of short stories, Shitkickers & Other Texas Stories, "I remembered back to my coming-out days in San Antonio, Texas, in the early 1960s and realized that I had lived long enough and been out long enough to be historic."20Carolyn Weathers, Shitkickers & Other Texas Stories (Los Angeles: Clothespin Fever Press, 1989), 13. "Cheers," then, while a testament to Weathers's lived experience, is also a mid-eighties reflection on pre-Stonewall LGBTQ+ life that is inflected with historical analysis. Writing "Cheers" as a bildungsroman—or coming-of-age tale whose generic conventions and narrative structure consist of tracing a character's psychological growth from youth to young adulthood—allowed Weathers to depict the gay cultural milieu she experienced in pre-Stonewall San Antonio while offering didactic historical messages about LGBTQ+ community formation, substance and alcohol abuse, political organizing, writing, and representation. These messages—conveyed through the political awakening of the story's protagonist—ultimately culminate in the text's primary theme: while the gay bar should be celebrated as the foundation of gay sociality—in that it enables community, friendships, and intimate relationships—it should also be critiqued for its limited ability to psychologically and physically sustain community. Political organizations and influence, LGBTQ+ self-representation, and LGBTQ+-owned businesses and cultural spaces, among other forms of community building and cohesion, are needed to combat systemic oppression and enhance LGBTQ+ people's quality of life.

Written from the third-person perspective of an unnamed narrator, the twenty-nine-page narrative mimics the experience of gay bar hopping, following the partying trail of Jane Jones (the protagonist and Weathers's fictional self) as she moves from The Acme to The Country to Fernando's Hideaway (all actual historical bars).21I originally accessed "Cheers Everybody!" in the Weathers Collection at ONE. However, the collection of short stories in which "Cheers" is included—Shitkickers & Other Texas Stories—can occasionally be found in used bookstores or on Amazon. Peopled with representations of Weathers's sister Brenda and friends, the story intersperses bar scenes with house parties, dinner dates, and downtime with lovers and friends. But the narrative's constant return to the bar suggests its centrality to gay life and community formation in early 1960s San Antonio. Although cities such as Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles were home to the burgeoning homophile movement during this time, which offered alternative, if similarly clandestine, spaces to those of the bar, scholars have neither discovered organized political activity associated with or inspired by organizations like the Daughters of Bilitis or the Mattachine Society in San Antonio, nor have individuals who participated in the pre-Stonewall San Antonio gay scene reported such activity.22As of publication, there are only two other academic studies of pre-Stonewall San Antonio: Melissa Gohlke's "Out in the Alamo City: Revealing San Antonio's Gay and Lesbian, World War II to the 1990s," (master's thesis, University of Texas at San Antonio, 2012); and Amy Stone's Cornyation: San Antonio's Outrageous Fiesta Tradition (San Antonio: Maverick Books, 2017)—from which her article, "Crowning King Anchovy," condenses information. While ONE, a monthly magazine published by ONE, Inc., a gay rights organization founded in Los Angeles in 1952, was available for purchase in San Antonio, Weathers remembers "coming out when there was absolutely nothing but the bars—no thought or hope that there would ever be anything else."23Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy," 300; Amy Stone and Craig Lofton, personal email, August 21, 2013. Stone writes, "Bars, coffee shops, and newsstands that sold ONE Magazine sprang up on the edges of Travis Park, a downtown green space known as a meeting place for gay men"; Weathers, Shitkickers, 13. In short, the gay bar was then the only established subcultural space for gay people to meet other gay people in San Antonio. These gay bars, as Weathers told me, serviced a mixed-gender crowd of men and women on a daily basis and were the source of friendships, hook-ups, and committed relationships. Throughout this essay, I consciously deploy the terms gay and gay women rather than lesbian when referencing patrons of these bars because Weathers specified that lesbian was not used in the gay San Antonio scene when she was there.

"Cheers" opens with the narrator describing Jane's giddy investment in absorbing and understanding the new gay world that her older sister, Diane, has introduced her to, highlighting Weathers's understanding of the gay bar as an important source of visibility, sociality, and community building in San Antonio:

Jane Jones took everything in. The Acme Bar was packed. Everyone knew most everyone, and she was learning. The Acme Bar was no rathole to her. It was an enchanted room, the first gay bar Diane and Maria took her to when she arrived in the colorful, picturesque city of San Antonio from West Texas two weeks earlier.24Weathers, Shitkickers, 19.

As Jane immerses herself in the gay bar scene, she experiences multiple complicated love affairs, establishes a network of friends, and transitions from the youthful exuberance of initially coming out—as depicted in this first scene—to a more critical and politicized approach towards gay life and experience. She learns how everyday homophobia and institutions such as law enforcement and the military affect gay livelihood.

"Cheers" features military personnel in civilian life through two primary characters, Nan Grinder and Maria, based, respectively, on a mutual friend of the Weathers sisters known as Liz and a lover of Brenda Weathers named Anita Ornelas.25Weathers, interview by author. Nan and Maria are enlisted as WACs (Women's Army Corps).26Founded in 1942 as the women's branch of the US Army, the Women's Army Corps existed until 1978, when it was disbanded as the Army implemented gender-integrated units. The former is notorious for her paranoia and alcoholism while the latter is characterized as a hard-working soldier who exudes "patriotism and earnestness."27Weathers, Shitkickers, 29. Weathers uses this character foiling to point to the precarious existence that all gay WACs, regardless of personalities or work ethic, faced in the homophobic armed forces. For instance, Maria's goal of attaining the Good Conduct Medal is quashed when she's late to guard duty after trying to cover for two gay women making out on base. The next day two gay WACs—Sergeant Rusty and Sergeant Scaggs—report Stacey, one of the women from the make out session, for homosexual activity. Rusty and Scaggs had been "fixtures at Nan Grinder's martini parties," which she would throw as a cover for herself each time she slept with a woman.28Weathers, Shitkickers, 30. Their actions result in Nan's becoming a reclusive shut-in as she fears that anyone, regardless of sexual identity, will potentially out her to military authorities and end her career. All of these experiences paint the military as a dead end for solidarity or long-term community building among gay women. And Weathers's depiction is not unfounded, as oral histories of WACs recorded by Allan Bérubé in Coming Out Under Fire, along with studies of the climate of fear and vast purging of homosexuals in the government and military during this period, such as David K. Johnson's The Lavender Scare, attest to the power dynamics and political tactics forced upon and performed by gay WACs as a means of survival.29David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Alongside this bleak outlook on the possibility for gay women's community, Weathers includes descriptions of the WAC Shack, a bar for WACs only, to document historical experience while alluding to a future of lesbian bars that would fulfill desires for queer women's space. In "Cheers" and in her interview, Weathers frames the WAC Shack as a source of speculation and fantasy among civilian women who wondered what it must be like to patronize a bar full of women. Although the homosociality of the WAC Shack enabled women to potentially recognize their same-sex desire and offered a place of female bonding, its idealization by gay civilians negated the reality of gay WACs who had to navigate the space. While a place of sociality, the WAC Shack, more so than civilian gay bars, was also a place where patrons would worry that any homosexual behavior would be reported to military officials.

Desire for a queer future also appears when Jane fantasizes about positive cultural representations and access to LGBTQ+ writing. As one friend proudly shows off a book that pathologizes homosexuality and sings the praises of The Children's Hour, Jane asks, "Wouldn't it be something . . . if there were gay bookstores?"30Weathers, Shitkickers, 38. Based on Lillian Hellman's 1934 play of the same name, The Children's Hour (1961) was directed by William Wyler and featured Audrey Hepburn (Karen) and Shirley MacLaine (Martha). Falsely accused of lesbianism by a vindictive student, Karen and Martha, teachers at a private school for girls, get caught up in negative media coverage that isolates them. The film ends in Martha's suicide, as she realizes that she has loved Karen all along and feels responsible for their public humiliation and Karen's failed marriage engagement. "You mean," asks another friend, "bookstores with only gay books in them." "Yeah," Jane replies, "that said nice things."31Weathers, Shitkickers, 38. The group's response is partly cynical ("She wants the world"), partly optimistic ("You never know").32Weathers, Shitkickers, 39. Here, in a story set in the 1960s but self-published in 1987, Weathers invokes the Women in Print Movement, in which she was involved as a publisher and writer. From the late 1960s through the 1980s, feminist and lesbian-feminist print cultures flourished in numerous small towns and cities, with women-run collectives and presses churning out journals, newspapers, newsletters, magazines, novels, poetry chapbooks, etc. These artifacts, as well as their byways—or their sharing by word of mouth, conferences, meetings, feminist and lesbian-feminist bookstores, and the mail—make up what recent scholarship terms the Women in Print Movement (WIPM).33Jaime Harker, The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 17. For more histories of the WIPM, see Agatha Beins, Liberation in Print: Feminist Periodicals and Social Movement Identity (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017); Victoria Hesford, Feeling Women's Liberation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013); Kathryn Thoms Flannery, Feminist Literacies: 1968–75 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010); Julie R. Enszer, "A Fine Bind: Lesbian-Feminist Publishing from 1969 through 2009" (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 2013); and Kristen Hogan, The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). The WIPM provided spaces for women to hone their fiction, poetry, and nonfiction writing, as well as sociopolitical analyses; it also generated connections between nodes of the movement throughout the United States, creating a feminist network with stronger organizing capabilities at local, state, and national levels.

These moments of political awakening in "Cheers" further character development within the narrative arc of the bildungsroman and help codify the story's primary theme, both of which are fully rendered in the final scene. In contrast to the opening scene, which depicts an elated novice Jane responding to The Acme, the final scene is contemplative, featuring recognition among Jane and her friends that something needs to change. Trying to figure out what to do on a sweltering San Antonio day, one friend suggests a scored game of throwing pebbles at birds, and Jane replies:

Nan used to . . . only she used rocks; come home from work and right away, after mixing up martinis, go out to her back porch and chonk rocks at the little birds; busted their little heads, too; never winced, never smiled, never nothing; just grim, grim, grim.

No one spoke for a time, just looked at one another and down at the ground. Jane felt there was surely something hanging in the oppressive air. It did not seem to be rain, but no one was sure. It had to break soon. They still did not know what to do.34Weathers, Shitkickers, 44.

This shared emotional response builds upon the story's central engagement with the day-to-day struggles of gay men and women and disenchantment that the story increasingly conveys through Nan, Jane, and her sister, Diane. By the story's end, Nan's mental and physical deterioration disturbs all of her former associates, particularly Jane, while Diane, bored and restless with the daily nine-to-five and happy hour at the bar, considers a move to California. Jane, aware of her own mortality while standing on a concrete ledge overlooking the San Antonio River, realizes that her reckless behavior—her cavalier tempting of death through hard drug abuse and an eating disorder—will eventually kill her. The sociality of the gay bar can neither change the homophobic military regulations that have impacted the mental and physical health of Nan Grinder, provide the environment Jane needs to get sober, nor give Diane the intellectual stimulation, political activism, and sense of purpose that she desires. But rather than gesture towards political organizations, therapy, or social networks beyond the gay bar, the group remains silent until Jane suggests that they go to the bar, which they do.35Weathers, Shitkickers, 44.

In early 1960s San Antonio, the bar remains a necessary distraction and needed escape. Weathers's prefatory words to the story resonate here: "I remember coming out when there was absolutely nothing but the bars—no thought or hope that there would ever be anything else."36Weathers, Shitkickers, 13. By the end of "Cheers," its narrator believes that "the something . . . hanging in the oppressive air" will "break soon."37Weathers, Shitkickers, 44. While historiographical and cultural tendencies to narrativize LGBTQ+ liberation as beginning with the 1969 Stonewall riots38This was a series of violent riots within the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City that was set off by a police raid of the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. have come under critique for erasing previous LGBTQ+ activism or dismissing it as more assimilative than radical, Weathers's account in "Cheers" offers documentary testimony through the thin guise of fiction for how some queer people who did not have access to organized political groups understood their lived experience at one time (1960s) and place (San Antonio).39See, for instance, Elizabeth A. Armstrong and Suzanna M. Crage, "Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth," American Sociological Review 71, no. 5 (2006): 724–751; Craig A. Rimmerman, The Lesbian and Gay Movements: Assimilation or Liberation? (New York: Routledge, 2014).

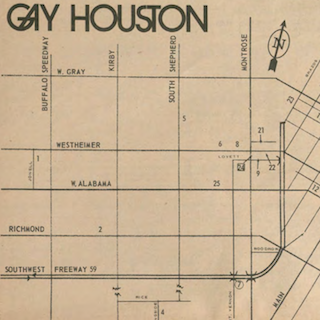

Although "Cheers" describes the centrality of bars to gay life in pre-Stonewall San Antonio, it reveals little about how issues of race and class inflected gay experience in the city at this time. Photographs of these gay bars that Weathers took as a patron hint at racial demographics, but further contextualization of these spaces provided by my interview with her shows that while fluid and mixed in terms of class demographics, these gay bars' racial demographics were very much pre- and over-determined by Jim Crow racial segregation. Of the bar sketches that follow, all of them but Mary Ellen's Top Hat—located at 210 South New Braunfels Avenue in Figure 3—appear in "Cheers," and each sketch will offer deeper insight (through the use of Weathers's personal reflections in our interview) into the racialization of San Antonio gay bars than is provided in Weathers's autobiographical short story. Figure 3 also notes locations for The Acme (505 Austin Street)—the first bar that Weathers entered when she moved to San Antonio and the bar "Jane" first encounters in "Cheers"—the River Walk, and Five Points. Fernando's Hideaway, as depicted in "Cheers" and told to me by Weathers, was located on the River Walk.40Weathers, interview by author. In her thesis, Gohlke locates Fernando's Hideaway at 2100 Frio City Road, but she provides no information about the bar beyond that. It is unclear whether this is a discrepancy in information or Fernando's moved locations at some point. Besides Fernando's Hideaway and The Country II, Gohlke's study does not document the bars that I discuss here. See Gohlke, "Out in the Alamo City." Five Points serves as visual orientation for Fredericksburg Road (to its immediate northwest), which led out to The Country (address now lost).

The Acme

In "Cheers," the narrator describes the neighborhood where The Acme is located, at 505 Austin Street on the outskirts of downtown, as "an eerie area of locked warehouses and abandoned storefronts where life had left, as though an alien spaceship had beamed everyone else up during the night."41Weathers, Shitkickers, 15. A tiny little dive bar, or as Weathers called it, "a dump," The Acme was very popular, always "stuffed full of gay men and women." The co-owners, fictionalized as Ray Davis and Lila Tankersley in "Cheers," were an amiable white gay man and a white elderly woman who Weathers believes was asexual. "Lila" also owned a shop next door called The Acme Pharmacy and had a reputation for hassling patrons of the bar, insisting that they produce their IDs. Unsure of how these two became business partners, Weathers noted that the bar serviced a mixed crowd of civilian and military, working class and upper class, gay folk and occasionally heterosexual couples. For instance, a straight couple, the Rodriguezes, "would come in and join [them] for hamburgers and beers." When asked about the racial make up of the bars, specifically if they were interracial, Weathers specified that Mexican Americans and whites mingled in all San Antonio gay bars, but that this wasn't viewed as interracial mingling because Mexican American and Anglo cultures were heavily intertwined in San Antonio. The idea of race as something that marked Mexican Americans and Anglos as apart from or different from each other became more apparent to her when she moved to Los Angeles, where she was "surprised by how segregated Mexicans and whites were."42Weathers, interview by author.

Given the long history of anti-Brown violence and political disenfranchisement in south, central, and west Texas, if my informant had been a Mexican American woman, then she would have likely told a different story about race. But Weathers's account offers insight into white experience of racial intimacy in San Antonio, while also alluding to potential Mexican American identification with whiteness as produced by San Antonio's colonial and military history. South, central, and west Texas—parts of which were included in the territory of the Republic of Texas and parts of which were considered contested territory between Mexico and Texas until US annexation and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (refer back to Figure 1)—have traditionally homed the majority of the state's Latino demographic. Latino populations in north and east Texas have increased in recent years, particularly in Houston and the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. However, because these areas were heavily settled post–Mexican Independence by Anglos practicing chattel slavery, they have been and continue to be home to most of Texas's Black demographic.43See "The Changing Population of the Texas and the Tyler Region," (Tyler: Texas Demographic Center, 2017), https://demographics.texas.gov/Resources/Presentations/OSD/2017/

2017_03_21_TylerCatalyst100.pdf. Figure 4 presents a map of Texas's Black enslaved population in 1845, and Figure 5 a map of Black demographics by Texas county as of 2020–2021. Consequently, the establishment of white supremacy in Texas, in its republic and later state forms, required regionally specific racialized policing practices. Whereas east Texas followed the rest of the US South in contending with white over Black, south, central, and west Texas had to contend with white over Black and Brown.44These regionally specific racialized policing practices are not transhistorical—although their afterlives or permutations of them are—and shift according to changing racial demographics. For instance, by the early 1970s, Houston had a significant Latino demographic in comparison to the rest of predominately rural east Texas. Consequently, as Guadalupe San Miguel Jr. documents in Brown, Not White: School Integration and the Chicano Movement in Houston (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005), Houston Independent School District tried to avoid integrating white and Black students by classifying Latinos as white. That is, Latino and Black students would be integrated, while white students would attend separate institutions.

While the legal practice of chattel slavery meant whites maintained control over Black individuals throughout Texas in its various iterations as province, republic, and state, shortly after the Texas Revolution, alliances between Texians and Tejanos unraveled. Whites in south, central, and west Texas removed Tejanos from positions in government and public office and committed rapes, lynchings, and massacres as a means to assert dominance and instill fear. Although Tejanos enlisted and served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, the emancipation of enslaved Black people and the white power grab post-Reconstruction to reassert social structures and hierarchies of old that enabled the monitoring and control of Black bodies necessitated the creation of Jim Crow laws, which in south, central, and west Texas were accompanied by Juan Crow laws. Not only intended to ensure Black and Brown disenfranchisement in such forms as voter suppression, racist housing policies, and underfunded educational institutions, Juan and Jim Crow instantiated tripartite racial segregation in an effort to explicitly convey white supremacy and racial difference from Mexican Americans and Black people while also deterring Black and Brown coalitions.45For further information, consult the following: Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987); William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928 (London: Oxford University Press, 2017); David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987); and Nicholas Villanueva Jr., The Lynching of Mexicans in the Texas Borderlands (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018). Analyzing Mexican American and Black civil rights movements from the early to mid-twentieth century in Texas, Brian D. Behnken argues that Juan and Jim Crow were, by and large, effective in encouraging Black and Mexican Americans to "work against each other" politically.46Brian D. Behnken, Fighting Their Own Battles: Mexican Americans, African Americans, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Texas (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 230. Political organizations such as the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) "sought to include Mexican Americans on the white side of Jim Crow," and some Mexican Americans sought to prove their whiteness through anti-Black practices and violence, such as denying Black people service and setting off bombs in Black homes.47Behnken, Fighting, 68. Specifically, Behnken references a 1950 bombing in South Dallas, in which 15 bombs were detonated at the homes of Black residents who had integrated a white neighborhood. While there were multiple vigilantes involved, many of whom were never apprehended, two suspects were Mexican American men who felt threatened by the presence of Black residents in white neighborhoods. As Behnken elaborates, this political strategy wasn't successful in gaining Mexican Americans long-term equal rights, but many whites, including Texas governors of the period, did "[recognize] Mexican American whiteness," thus demonstrating the malleability of whiteness or how false promises of inclusion within white racial identity were deployed to further anti-Black and Brown sentiment while shoring up white supremacy.48Behnken, 40. Given these racial dynamics, Weathers's words about white and Mexican American mingling in San Antonio gay bars reflect Sharon Holland's thoughts on racial intimacy: rather than tamping down racist ideologies and practices, "proximity and familiarity" might actually "replicate the terms upon which difference is articulated and therefore maintained."49Sharon Patricia Holland, The Erotic Life of Racism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 19.

Fernando's Hideaway

Inspired by the Mexican American bar owner's name and a popular song ("Hernando's Hideaway"), Fernando's Hideaway was in a historic building along the San Antonio River Walk. Construction on the River Walk began in the 1920s, when the city hired engineers to create a dam system that would address the frequent threats of disastrous flooding by the San Antonio River. Plans to convert the river and its banks into a storm sewer system resulted in the founding of the San Antonio Conservation Society, which successfully lobbied against this measure and was tasked with overseeing future development of the area. Delayed by the Great Depression, the River Project—plans to develop the river by adding restaurants, walkways, and shops—was initiated in 1939 through local tax and WPA (Works Progress Administration) funding. Initially headed by architect Robert H. Hugman and later J. Fred Buenz, construction on the River Project by WPA workers ended in 1940, with an opening dedication ceremony coinciding with the city's inaugural Fiesta River Parade in April of 1941. Throughout the forties and fifties, the River Walk featured a small sampling of restaurants, shops, and boating activities that drew in a fair number of locals and tourists alike but was generally considered an unsafe area at night due to crime. From the 1960s up until 2011, however, the face and reputation of the River Walk radically changed, as the city heavily invested in its further development and expansion in order to capitalize on tourism capabilities.50Consult these sources for a more detailed history and timeline: Lewis F. Fisher, "San Antonio River Walk [Paseo del Rio]," Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 20, 2019, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hps02; "History of the River Walk," The San Antonio River Walk, accessed April 20, 2019, https://www.thesanantonioriverwalk.com/history/history-of-the-river-walk; City of San Antonio, "River Walk," accessed April 20, 2019, https://www.sanantonio.gov/CCDO/riverwalk.

Attentive to the River Walk milieu of Fernando's Hideaway, scenes of the bar in "Cheers" occur amid Fiesta San Antonio, an annual ten-day celebration of the city's history and culture, which started in 1891 to commemorate those fallen at the battles of the Alamo and San Jacinto. According to Weathers, Fernando's was much "fancier" than the other bars and not as "secretive," given its location in an area with heavy foot traffic. The racial, gender, and class make-up of the bar was like The Acme, with straight people often patronizing it as well. The bar's balcony that overlooked the river was a popular spot, and Weathers laughingly recalled a Fiesta memory of Navy men floating in a boat down the river as gay men catcalled "sea food" from the balcony.51Weathers, interview by author. The fact that gay men and women weren't discouraged from patronizing Fernando's despite its public visibility speaks to the assimilative capabilities of white and Mexican American gay bars in the downtown San Antonio district during this period. As Amy L. Stone's work on Cornyation (a mock debutante pageant organized and performed by gay men during Fiesta from 1951 to 1964) reveals, spaces and events associated with Fiesta often allowed for gay visibility within certain limits. "Attended by a public audience of thousands and reviewed in local newspapers," Cornyation, Stone argues, "rendered gay culture visible to some heterosexual observers and implicated gay men as urban citizens worthy of integration into the city," but "this legibility ultimately led festival organizers to ban Cornyation."52Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy," 298. Given Fernando's proximity to Fiesta activities held on and near the River Walk, as well as its accessibility to tourists, perhaps it's plausible to suggest that the general public did not necessarily recognize it as a gay bar and that its existence was contingent, in part, on it servicing a large heterosexual demographic.

The Country

The Country featured in "Cheers" was located outside the city limits on Fredericksburg Road. It is also referred to as Stein's Bar in the short story, but the actual name for it—when folks did not invoke its nickname, The Country—was Kline's Bar. Two white elderly lesbians, Maybelle and Bee, operated The Country and had probably been together since the 1930s. Weathers described The Country as much "nicer" than The Acme: it "sat in some thickets" off the road and had "long tables" and a jukebox in its "cavernous dance hall." Moreover, there was a separate lounge room with a bar at the front of The Country where customers could relax on chairs and sofas while purchasing drinks. The racial, gender, and class demographics of The Country mirrored The Acme's, with many people frequenting both of these bars. This shared patronage was not just because The Country had more room and was the site of "a lot of drunkenness and singing loud to Patsy Cline," but also because gay couples could dance at The Country. Unlike urban gay bars, which didn't allow same-sex dancing due to their close proximity to police stations, The Country permitted same-sex dancing because its distance from police stations gave the bar owners and patrons time to warn each other and switch into heterosexual pairs.53Weathers, interview by author.

Military and Bexar County police occasionally raided The Country, and Weathers, having witnessed one of these raids, fictionalizes the method employed to alert patrons in a way that is very similar to the actual method she shared with me in person: Maybelle would walk around with her yellow bandana in her shirt pocket, which was a sign that cops were coming, and same-sex couples would immediately rearrange into heterosexual pairs. Another precaution included banning two people in the bathroom at once because if, for example, two women were in the ladies restroom during a raid, cops had probable cause to arrest them for homosexual behavior. When the cops entered the bar, "they would," according to Weathers, "go around the room looking for a woman's hand on another woman's knee" or any type of same-sex touching. I asked her if authorities persecuted gay men and women if they dressed in clothes typically associated with the opposite sex, as in, for example, Buffalo, New York, where butches were arrested for wearing less than three articles of women's clothing, and she said gay men and women in San Antonio wore the same casual dress clothes as heterosexuals: "jeans, t-shirts, Bermuda shorts."54An informant recounts this in Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis's Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (New York: Routledge, 1993). By her account, there weren't butch–femme pairings in the gay scene, and people didn't use those terms; instead, the only term used was fluff, which referred to more feminine women. Outside of this specification, Weathers's remarks also suggest that drag was not a common feature in these bars, nor was there a significant presence of people presenting as gender variant.55Weathers, interview by author.

For reasons that Weathers can't remember, Maybelle and Bee ended up closing The Country. A white gay man and white bisexual woman with an arranged heterosexual marriage opened a similar venue called The Country II in a different location not long after.56Weathers, interview by author. In her study of San Antonio gay bars, Gohlke explains that like The Country, this bar was a queer gathering space that allowed for same-sex dancing and touching due to its location outside the city limits. The patrons and bar owners also employed their own technique for warning of incoming cops: flashing the lights on and off.57Gohlke, "Out in the Alamo City." Gohlke and Weathers have been in contact with each other, and Weathers told me that The Country referred to in Gohlke's thesis is, in fact, The Country II. The Country's function as a queer space on the city's periphery that gay people fluctuated between in the process of creating queer community resonates with John Howard's idea of circulating, which he uses to account for how gay men in Cold War Mississippi engendered queer experience and space by remaining in a state of flux.58John Howard, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 78.

Mary Ellen's Top Hat

Located at 210 South New Braunfels Avenue on the city's east side, a traditionally Black neighborhood since formerly enslaved people began establishing Freedmen's Towns there after the Civil War, Mary Ellen's Top Hat is the final bar that Weathers remembers from her time in San Antonio.59For more information about Black history and experience in San Antonio, see Alwyn Barr, Black Texans: A History of African Americans in Texas, 1528–1995 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996); Bruce A. Glasrud, ed., African Americans in South Texas History (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011); Kenneth Mason, African Americans and Race Relations in San Antonio, Texas, 1867–1937 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998). Owned by a heterosexual Black woman of the same name, Mary Ellen's was unique because it welcomed Black, Mexican American, and Anglo patrons. According to Weathers, during their revelry at the bar, Mary Ellen would sing Ray Charles songs and Weathers and her friends would act as Mary Ellen's chorus. The bar also had a beer-drinking club called UN CAPPA-FU—a play on "uncap a few." As an interracial space, Mary Ellen's heightened Weathers's awareness about Black experience in the United States through conversations she had with Mary Ellen, a Black male acquaintance nicknamed Mr. Elegance, and white and Mexican American friends and fellow patrons. Becoming noticeably emotional when discussing the racial dynamics of this bar, Weathers recalled that she, Mary Ellen, and Mr. Elegance decided to integrate The Country one night after a heated discussion over Black civil rights. However, they left in separate vehicles, and upon arriving at The Country, Weathers went in without waiting for them. She doesn't know if they were denied entrance or if they even showed up, and that lack of knowledge, as well as her failure to wait for them, is a source of strong regret today.60Weathers, interview by author.

Although heavy media coverage of the civil rights movement brought images of violence and struggle into the everyday lives of white people across the country, when Weathers entered the San Antonio gay bar scene in her early twenties, she was still ignorant and indifferent due to her race, youth, and regional upbringing. Recall that west Texas has always had a significantly smaller Black population in comparison to other parts of the state, which has influenced how anti-Black practices and ideologies manifest and circulate there. West Texas officials did not always enforce Jim Crow laws to the extent that they were enforced in more eastern parts of the state, and anti-Mexican sentiment often predominated among locals given the region's colonial history and significant Latino demographic.61William S. Osborn, "Curtains for Jim Crow: Law, Race, and the Texas Railroads," Southwestern Historical Quarterly 105, no. 3 (2002): 395. The small, predominately white town that Weathers grew up in, Brownfield, was no exception. She struggled to remember incidents of anti-Black violence and racism in her childhood, quickly adding, however, that she did notice anti-Mexican sentiment, especially in relation to the presence of imported Mexican agricultural workers in Brownfield. Weathers's experiences in Mary Ellen's Top Hat reveal that, in facilitating cross-racial dialogue, racially integrated gay bars in San Antonio were potential sites of racial consciousness raising, however limited, among patrons.62Weathers, interview by author.

Conclusion

Absent in these bar sketches are the voices of people of color such as Anita, or Fernando, or Mary Ellen, or Mr. Elegance. What might a Black-owned gay bar have meant to someone like Mr. Elegance? What were his and Mary Ellen's thoughts about gay bars like The Country upholding anti-Black Jim Crow laws? Was Mary Ellen's Top Hat racially integrated because under Jim Crow, white people actually had access to all spaces, or was it a political statement on Mary Ellen's behalf? What did it mean to a Mexican American bar owner like Fernando to deny services to Black gay people and Black people generally? As a Mexican American woman, what was Anita's experience of racism and racialization as she moved from Mexican American-owned bars to white-owned bars to Black-owned bars? The Weathers Collection at the ONE Archives cannot answer these questions, but they should prompt us to consider what research approaches and archival practices are needed to adequately represent a fuller and more inclusive queer history of pre-Stonewall San Antonio and Texas. Now is the time to gather oral histories and create cross-reference lists of Texas queer experience in LGBTQ+, Black, Latino, and Asian American archives so that the research process is streamlined for academics and non-academics invested in interpreting and preserving this history.

Beyond this call to further curate and study Texas queer history, my analysis here does open up other questions that could be more thoroughly explored in future work with the Weathers Collection. For instance, how did military history influence racial dynamics in San Antonio? How might sexual dynamics be understood through the city's colonial history? What were common or popular understandings of gender in the gay community at the time? These are just a few provocations that readers might find in this essay. From this work, I hope readers will notice the gap in racial awareness when considering Weathers's "Cheers" short story and our later interview. That is, the short story itself does not discuss Jim Crow segregation or the different racialized experiences of characters. In fact, none of the characters are openly racialized. If it were not for my interview with Weathers, I could not have provided an analysis of racialized gay space in San Antonio at this time. Both text and context, story and oral history, work together to tell a richer, if still incomplete, version of pre-Stonewall gay life in San Antonio. This essay, then, might serve as an object lesson in how to work with racial silences that are often common in the archival materials of white subjects. And considering that one of the problems of archives—LGBTQ+ and otherwise—is the over-predominance of collections from white subjects, this is not an object lesson to easily cast aside.

About the Author

Amanda Mixon is Assistant Professor of Instruction in the Center for Women's and Gender Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. Her research on US social movements has appeared in the Journal of Lesbian Studies and received support from the American Association of University Women, Duke University, the University of Virginia, and the University of California, Irvine Humanities Center.

Recommended Resources

Text

Bérubé, Allan. Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two. New York: Plume, 1991.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Faderman, Lillian. Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Howard, John, ed. Carryin' On in the Lesbian and Gay South. New York: NYU Press, 1997.

———. Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Black. Queer. Southern. Women.: An Oral History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

———. Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Kennedy, Elizabeth Lapovsky, and Madeline D. Davis. Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Quesada, Uriel, Letitia Gomez and Salvador Vidal-Ortiz, eds. Queer Brown Voices: Personal Narratives of Latina/o LGBT Activism. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015.

Sears, James T. Lonely Hunters: An Oral History of Lesbian and Gay Southern Life, 1948–1968. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

———. Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Stone, Amy L. Cornyation: San Antonio's Outrageous Fiesta Tradition. San Antonio, Texas: Maverick Books, 2017.

———. "Crowning King Anchovy: Cold War Gay Visibility in San Antonio's Urban Festival," Journal of the History of Sexuality 25, no. 2 (2016): 297–322.

Thompson, Brock. The Un-Natural State: Arkansas and the Queer South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010.

Web

Gohlke, Melissa. "Off-Limits and Out-of Bounds, World War II and San Antonio's Queer Community." Top Shelf: A Blog About Special Collections at the UTSA Libraries. February 25, 2013. https://utsalibrariestopshelf.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/off-limits-and-out-of-bounds-world-war-ii-and-san-antonios-queer-community/.

———. "San Antonio's Drag Culture of the 1930s and 40s." Top Shelf: A Blog About Special Collections at the UTSA Libraries. October 22, 2012. https://utsalibrariestopshelf.wordpress.com/2012/10/22/san-antonios-drag-culture/.

Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://www.tshaonline.org/home.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Archive. University of North Texas Libraries. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://library.unt.edu/special-collections/archives-manuscripts/lgbtq-archive/.

ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. University of Southern California Libraries. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://one.usc.edu/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | I follow Michael Omi and Howard Winant's definition of racialization: "the extension of racial meaning to a previously racially unclassified social relationship, social practice or group." Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2014), 111. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Besides the studies of San Antonio cited later in the essay, some relevant theses and dissertations of interest include: Kyle Edelbrock, "Taking it to the Streets: The History of Gay Pride Parades in Dallas, Texas, 1972–1986" (master's thesis, University of North Texas, 2015); Carl J. Stoneham, "How Prophecy Got Her Queer Back: (Re)discovering the Prophetic at the Rainbow Lounge, 40 Years and Eight Minutes Later" (master's thesis, Texas Christian University, 2010); and John D. Goins, "Confronting Itself: The AIDS Crisis and the LGBT Community in Houston" (PhD diss., University of Houston, 2014). |

| 3. | The actions of those fallen at the Alamo were glorified in Texas history and culture, and today, the Alamo commemorative monument and museum helps attract around 37 million annual visitors to San Antonio, whose tourism and hospitality industry generated an estimated 15.2 billion dollars in 2017. |

| 4. | The newly independent Mexican government began as the First Empire of Mexico headed by Agustín de Iturbide (1822–1823) before transitioning into a federal republic, with the Constitution of 1824 officially establishing the First Mexican Republic (Primera República Federal), known as the United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos). As the EUM sorted out its leadership and organizational structure, it failed to exert strong control and governance from Mexico City over the distant Tejas. Thus, the Mexican government's gradual steps towards abolishing slavery in 1829—which, in the eyes of many Anglo settlers, reneged on Iturbide's promise to let them practice chattel slavery in Tejas—and the prohibition of new Anglo settlers in the Law of April 6, 1830—which was precipitated by fears that the United States would annex Tejas and resulted in Mexican officials and troops being dispatched to enforce Mexican law in the province—encroached on the rights and privileges that settlers had grown accustomed to. The 1833 presidential election of Santa Anna only exacerbated these issues, as he threw out the Constitution of 1824, which allowed him to centralize control of the government by eradicating provincial or state governments, and also imprisoned Stephen F. Austin, the first empresario of Tejas and primary Texian representative, for a year. |

| 5. | Randolph B. Campbell, Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987). |

| 6. | Campbell, Gone to Texas; Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas. |

| 7. | John Manguso, "Fort Sam Houston," Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 1, 2019, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbf43; Robert Wooster, "Military History," Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 1, 2019, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qzmtg. |

| 8. | "2015 Military Economic Impact Study" (San Antonio, TX: Department of Government and Public Affairs, accessed July 1, 2021), https://www.sanantonio.gov/Portals/0/Files/OMA/EconImpact/2015SanAntonioMilitaryEconomicImpact.pdf?ver=2017-02-15-142835-893. |

| 9. | The United States Census Bureau designated San Antonio the fastest growing city in the United States in 2018: United States Census Bureau, "Census Bureau Reveals Fastest-Growing Large Cities," release number CB18-78, May 24, 2018, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/estimates-cities.html; "Texas Almanac: City Population History from 1850–2000," Texas Almanac, accessed April 5, 2019, https://texasalmanac.com/sites/default/files/images/CityPopHist%20web.pdf. |

| 10. | See Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (New York: Plume, 1991); George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994); and John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity" in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, edited by Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin (New York: Routledge, 1993), 467–476. |

| 11. | D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," 472. |

| 12. | Amy L. Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy: Cold War Gay Visibility in San Antonio's Urban Festival," Journal of the History of Sexuality 25, no. 2 (2016): 300. Also, see Melissa Gohlke's blog post about these nightclubs and female impersonators: "San Antonio's Drag Culture of the 1930s and 40s," The Top Shelf, October 22, 2012, https://utsalibrariestopshelf.wordpress.com/2012/10/22/san-antonios-drag-culture/. |

| 13. | Melissa Gohlke, "Off-Limits and Out of Bounds, World War II and San Antonio's Queer Community," The Top Shelf, February 25, 2013, https://utsalibrariestopshelf.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/off-limits-and-out-of-bounds-world-war-ii-and-san-antonios-queer-community/. |

| 14. | Gohlke, "Off-Limits." |

| 15. | For further specification on these procedures, see Bérubé, Coming Out under Fire; Chauncey, Gay New York; and Margot Canaday's The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). |

| 16. | Gohlke, "Off-Limits." |

| 17. | Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy," 299. |

| 18. | Weathers was featured on AM Los Angeles with Regis Philbin. In 1970, prior to the GLF raid of the APA's L.A. Convention, the GLF raided an APA convention in San Francisco. These raids were to protest the APA's classification of homosexuality as a mental illness. |

| 19. | Carolyn Weathers, interview by author, October 22, 2015, Long Beach, California, video recording. Biographical information is condensed from the interview. |

| 20. | Carolyn Weathers, Shitkickers & Other Texas Stories (Los Angeles: Clothespin Fever Press, 1989), 13. |

| 21. | I originally accessed "Cheers Everybody!" in the Weathers Collection at ONE. However, the collection of short stories in which "Cheers" is included—Shitkickers & Other Texas Stories—can occasionally be found in used bookstores or on Amazon. |

| 22. | As of publication, there are only two other academic studies of pre-Stonewall San Antonio: Melissa Gohlke's "Out in the Alamo City: Revealing San Antonio's Gay and Lesbian, World War II to the 1990s," (master's thesis, University of Texas at San Antonio, 2012); and Amy Stone's Cornyation: San Antonio's Outrageous Fiesta Tradition (San Antonio: Maverick Books, 2017)—from which her article, "Crowning King Anchovy," condenses information. |

| 23. | Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy," 300; Amy Stone and Craig Lofton, personal email, August 21, 2013. Stone writes, "Bars, coffee shops, and newsstands that sold ONE Magazine sprang up on the edges of Travis Park, a downtown green space known as a meeting place for gay men"; Weathers, Shitkickers, 13. |

| 24. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 19. |

| 25. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 26. | Founded in 1942 as the women's branch of the US Army, the Women's Army Corps existed until 1978, when it was disbanded as the Army implemented gender-integrated units. |

| 27. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 29. |

| 28. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 30. |

| 29. | David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). |

| 30. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 38. Based on Lillian Hellman's 1934 play of the same name, The Children's Hour (1961) was directed by William Wyler and featured Audrey Hepburn (Karen) and Shirley MacLaine (Martha). Falsely accused of lesbianism by a vindictive student, Karen and Martha, teachers at a private school for girls, get caught up in negative media coverage that isolates them. The film ends in Martha's suicide, as she realizes that she has loved Karen all along and feels responsible for their public humiliation and Karen's failed marriage engagement. |

| 31. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 38. |

| 32. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 39. |

| 33. | Jaime Harker, The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 17. For more histories of the WIPM, see Agatha Beins, Liberation in Print: Feminist Periodicals and Social Movement Identity (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017); Victoria Hesford, Feeling Women's Liberation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013); Kathryn Thoms Flannery, Feminist Literacies: 1968–75 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010); Julie R. Enszer, "A Fine Bind: Lesbian-Feminist Publishing from 1969 through 2009" (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 2013); and Kristen Hogan, The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). |

| 34. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 44. |

| 35. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 44. |

| 36. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 13. |

| 37. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 44. |

| 38. | This was a series of violent riots within the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City that was set off by a police raid of the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. |

| 39. | See, for instance, Elizabeth A. Armstrong and Suzanna M. Crage, "Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth," American Sociological Review 71, no. 5 (2006): 724–751; Craig A. Rimmerman, The Lesbian and Gay Movements: Assimilation or Liberation? (New York: Routledge, 2014). |

| 40. | Weathers, interview by author. In her thesis, Gohlke locates Fernando's Hideaway at 2100 Frio City Road, but she provides no information about the bar beyond that. It is unclear whether this is a discrepancy in information or Fernando's moved locations at some point. Besides Fernando's Hideaway and The Country II, Gohlke's study does not document the bars that I discuss here. See Gohlke, "Out in the Alamo City." |

| 41. | Weathers, Shitkickers, 15. |

| 42. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 43. | See "The Changing Population of the Texas and the Tyler Region," (Tyler: Texas Demographic Center, 2017), https://demographics.texas.gov/Resources/Presentations/OSD/2017/ 2017_03_21_TylerCatalyst100.pdf. |

| 44. | These regionally specific racialized policing practices are not transhistorical—although their afterlives or permutations of them are—and shift according to changing racial demographics. For instance, by the early 1970s, Houston had a significant Latino demographic in comparison to the rest of predominately rural east Texas. Consequently, as Guadalupe San Miguel Jr. documents in Brown, Not White: School Integration and the Chicano Movement in Houston (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005), Houston Independent School District tried to avoid integrating white and Black students by classifying Latinos as white. That is, Latino and Black students would be integrated, while white students would attend separate institutions. |

| 45. | For further information, consult the following: Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987); William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928 (London: Oxford University Press, 2017); David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987); and Nicholas Villanueva Jr., The Lynching of Mexicans in the Texas Borderlands (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018). |

| 46. | Brian D. Behnken, Fighting Their Own Battles: Mexican Americans, African Americans, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Texas (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 230. |

| 47. | Behnken, Fighting, 68. Specifically, Behnken references a 1950 bombing in South Dallas, in which 15 bombs were detonated at the homes of Black residents who had integrated a white neighborhood. While there were multiple vigilantes involved, many of whom were never apprehended, two suspects were Mexican American men who felt threatened by the presence of Black residents in white neighborhoods. |

| 48. | Behnken, 40. |

| 49. | Sharon Patricia Holland, The Erotic Life of Racism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 19. |

| 50. | Consult these sources for a more detailed history and timeline: Lewis F. Fisher, "San Antonio River Walk [Paseo del Rio]," Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 20, 2019, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hps02; "History of the River Walk," The San Antonio River Walk, accessed April 20, 2019, https://www.thesanantonioriverwalk.com/history/history-of-the-river-walk; City of San Antonio, "River Walk," accessed April 20, 2019, https://www.sanantonio.gov/CCDO/riverwalk. |

| 51. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 52. | Stone, "Crowning King Anchovy," 298. |

| 53. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 54. | An informant recounts this in Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis's Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (New York: Routledge, 1993). |

| 55. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 56. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 57. | Gohlke, "Out in the Alamo City." Gohlke and Weathers have been in contact with each other, and Weathers told me that The Country referred to in Gohlke's thesis is, in fact, The Country II. |

| 58. | John Howard, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 78. |

| 59. | For more information about Black history and experience in San Antonio, see Alwyn Barr, Black Texans: A History of African Americans in Texas, 1528–1995 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996); Bruce A. Glasrud, ed., African Americans in South Texas History (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011); Kenneth Mason, African Americans and Race Relations in San Antonio, Texas, 1867–1937 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998). |

| 60. | Weathers, interview by author. |

| 61. | William S. Osborn, "Curtains for Jim Crow: Law, Race, and the Texas Railroads," Southwestern Historical Quarterly 105, no. 3 (2002): 395. |

| 62. | Weathers, interview by author. |