Overview

The late nineteenth-century cyclorama painting of the Civil War Battle of Atlanta served as a technological, thematic, and commercial forerunner to D. W. Griffith's landmark 1915 film The Birth of a Nation. Both visual spectacles provided immersive experiences for mass audiences and popularized a celebratory account of history that paid tribute to white male warriors on both sides. These cycloramic and cinematic narratives propagated a militarized and racialized nationalism. (Take a virtual, guided tour of the Battle of Atlanta with Daniel Pollock. "The Battle of Atlanta: History and Remembrance." https://battle-of-atlanta.opentour.site/tours.)

The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting is a striking visual spectacle. The huge, circular panorama—371 feet long and 49 feet high—displays in vivid, you-are-there style one of the biggest clashes fought in the final ten months of the American Civil War. Exquisitely restored and reopened in February 2019 at the Atlanta History Center, the painting depicts Union forces repelling massive frontal assaults against their position east of the city on July 22, 1864. At the center of the combat action rides Federal Major General John A. Logan, the largest figure in the picture, charging toward the battle line and rallying his blue-coated troops in a large counterattack in the vicinity of the red brick Troup Hurt House. Logan's troops are shown forcing a mid-battle retreat of Confederate infantry units sent forward by their commanding general, John Bell Hood. The Confederate Army of Tennessee's setbacks at multiple points of attack during their eight-hour clash with the similarly named Federal Army of the Tennessee, coupled with the Yankees' retention of strategic high ground and a key railroad supply line, amounted to a major defensive victory for the Union forces.1Steven E. Woodworth, Nothing But Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 567–568.

At the end of the fighting on July 22, the Union Army of the Tennessee held its entrenched positions within cannon range of Atlanta, and the Confederate Army of Tennessee had lost a tenth of its fighting strength.2Gary Ecelbarger, The Day Dixie Died: The Battle of Atlanta (New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2010), 213–214. The Federal triumph presaged victories at nearby battlefields, Ezra Church and Jonesboro, six days and six weeks later, and the capture of Atlanta's three remaining rail lines by the end of August. Cut off from supplies, Hood ordered his troops to evacuate Atlanta on September 1, and the city's mayor surrendered to a Federal military advance party the next day. After Union troops marched into the city, their commanding general, William T. Sherman, sent a telegram to Washington, DC, announcing that "Atlanta is ours, and fairly won." This resounding end to Sherman's Atlanta campaign, combined with the Confederate loss of Mobile Bay and Union gains in the Shenandoah Valley, cinched Abraham Lincoln's reelection in November 1864 and portended the end of armed combat east of the Mississippi River in April 1865.3James M. McPherson, Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief (New York: The Penguin Press, 2014), 205; Brian Holden Reid, The Scourge of War: The Life of William Tecumseh Sherman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 330. Yet long after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, deep animosities between former Civil War adversaries continued, and paramilitary and mob violence against freedpeople and their descendants and allies went largely unchecked for decades.4Carole Emberton, Beyond Redemption: Race, Violence, and the American South After the Civil War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 146, 155, 201; Gregory P. Downs, The Second American Revolution: The Civil War-Era Struggle Over Cuba and the Rebirth of the American Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 136; Leon F. Litwack, "Hellhounds," in Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, ed. James Allen (Santa Fe, NM: Twin Palms Publishers, 1999), 8–37.

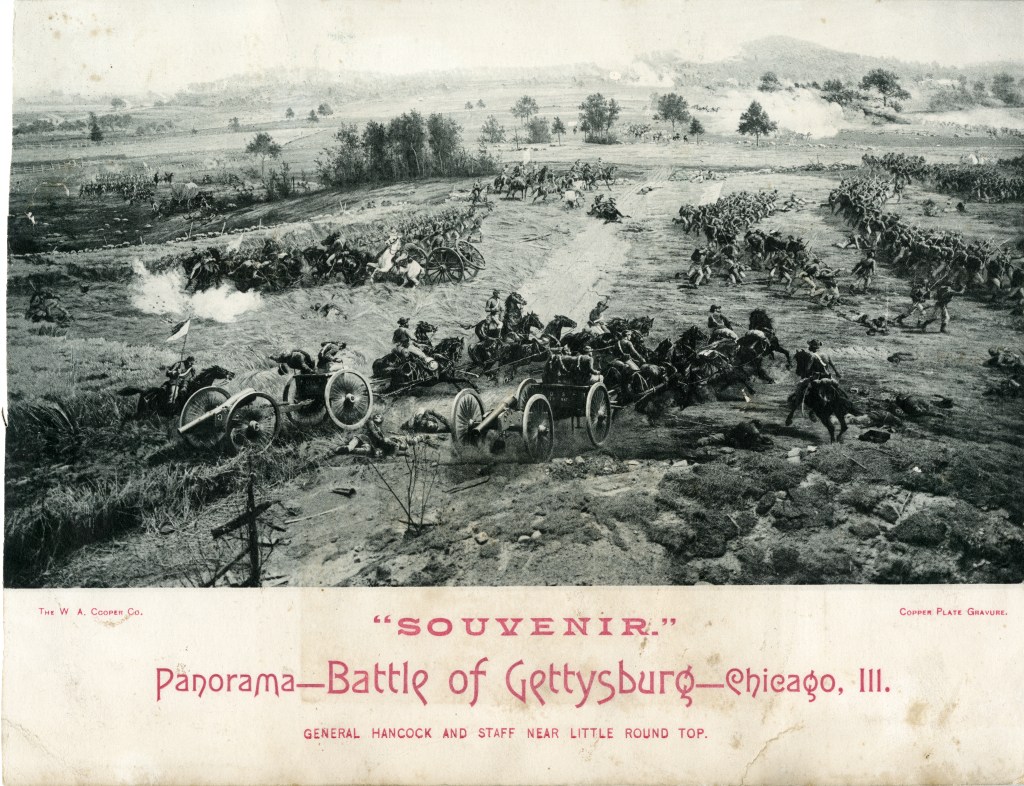

The seemingly endless resurrection, retelling, and reenacting of Civil War history, which continues to the present day, amounts to an ongoing contest between politicized versions of the past, the first renditions of which were produced by people for whom the War was a lived experience. Their commemorative creations included a myriad of images, texts, statues, reunions, Emancipation celebrations, and Memorial Days.5David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 31–97; Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 73–159. During the final decades of the nineteenth century, these inaugural forms of war remembrance mobilized identities, explanations, and emotions, and they framed political discourse about race, citizenship, and nationhood for years to come. Spectacular, immersive paintings of famous military clashes provided mass entertainment and compelling commemorative meanings for US audiences. At the peak of their popularity, from 1883 to approximately 1900, perhaps as many as three dozen Civil War battle panoramas in the cycloramic format toured cities throughout the US, and paintings of the Gettysburg and Vicksburg battles reached Australia and Japan.6Chris Brenneman and Sue Boardman, The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beattie, 2015), 14; Ralph Hyde, Panoramania! (London: Trefoil Publications, 1988), 172. Christ's crucifixion, vistas of the ancient world, and natural wonders and disasters were other popular cyclorama subjects.7Stephan Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 343; Angela Miller, "The Panorama, the Cinema, and the Emergence of the Spectacular," Wide Angle 18, no. 2 (1996): 35–69. The sweeping, proto-cinematic visual spectacles achieved enormous but ephemeral popularity; they anticipated but could not compete with motion pictures as an entertainment experience. Like the movies that followed, panoramas provided "a substitute reality presented with the revelatory force of the real."8Miller, "Panorama," 55. Yet, because the paintings presented an "image frozen in time," they lacked "cinema's possibilities for literal reenactment."9Alison Griffiths, "'Shivers Down Your Spine': Panoramas and the Origins of Cinematic Reenactment," Screen 44, no. 1 (2003): 1–37. As the popularity of cyclorama paintings waned, many of the enormous canvases disappeared while others were repurposed as theatrical production backdrops or cut up and sold as small remnants.10Antje Petty, "German Artists—American Cyclorama: A Nineteenth-Century Case of Transnational Cultural Transfer" (presentation, German Studies Association 34th Annual Conference, Oakland, CA, October 7–10, 2010, Oakland, CA), https://mki.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1100/2014/10/Petty_GSA-2010_Panorama.pdf. Today, among all Civil War battle panoramas, the Gettysburg and Atlanta cyclorama paintings are the only survivors on public display, each showcased in a twenty-first-century exhibition space. The Gettysburg panorama is shown at the national military park, located at the battle site in south central Pennsylvania, and the Atlanta image is exhibited at the city's history museum, approximately six miles from where the battle was fought.

This essay explores the history of the Battle of Atlanta painting, a surviving example of a fad that faded, which in its time expressed and exerted influence on Civil War memories north and south of the Mason Dixon line and served as a technological, thematic, and commercial forerunner to epic cinematic narratives, most notably D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation. As the original version of the Atlanta panorama and an identical copy circulated from city to city, following debuts in Minneapolis in 1886 and Detroit in 1887, the painting's visual retelling of a famous fight validated martial heroics on each side, which meshed with the continuing devotion of many viewers to their side's cause. At the same time, the Atlanta panorama also celebrated an underlying bond between the white male opponents by suggesting that their shared traits, beliefs, and traditions accounted for a common bravery in battle and a sense of common white Americanness that surged in the nineteenth century's final years. The painting expressed and helped perpetuate a militarized commemorative culture that supported a white national identity and abandoned a commitment to Black Americans' civil rights. Peaking in attendance amid a mounting but far from uniform movement toward sectional reconciliation, the Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting was most importantly a spectacle of a resurgent and increasingly militant and racialized American nationalism. Further, the panorama served as a precursor to D. W. Griffith's extravaganza, which depicted the Civil War and Reconstruction as the historical antecedents for a nationwide regime of white supremacy. In an era when spectacle culture rose rapidly and new, immersive visual entertainments competed for public attention, the Battle of Atlanta panorama and The Birth of a Nation illustrate how vivid and enduring images of a cataclysmic era captured the attention of throngs of people and encouraged their commitments to a narrowly configured version of American nationalism.11Susan Tenneriello, Spectacle Culture and American Identity: 1815–1940 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 2–14.

In its heyday, the Atlanta panorama, like other cyclorama battle paintings, was a travelling attraction. A team of European artists working in an American studio produced two identical versions of the Atlanta painting, and promoters moved each canvas from city to city for exhibition. At every stop, riggers installed the panorama in a massive rotunda building, a specially designed structure that enabled visitors to experience "being swallowed up in an imaginary world" while distancing them from their actual surroundings outside.12Evelyn J. Fruitema and Paul A. Zoetmulder, eds. The Panorama Phenomenon: Mesdag Panorama 1881–1981 (The Hague, Netherlands: Foundation for the Preservation of the Centenarian Panorama, 1981), 18. A darkened entrance hall, indoor lighting that brilliantly illuminated the sprawling battlefield tableaux, and a faux terrain—foreground settings with three-dimensional objects—connected almost imperceptibly to the bottom edge of the painted canvas served in unison to absorb spectators into an illusory reality. A meticulously realistic depiction of Atlanta's battlefield topography, military uniforms and equipment, combat events, notable commanders, and amassed infantry were popular features. Spectators were inserted within the 360-degree panorama, which provided an immersive, all-encompassing view of a historic clash. The spectacular visual narrative combined convincing optical illusions with vivid documentary realism, minus gory images of the dead and wounded. Although the artists and promoters aspired to authenticity, the battle story they "lifted from life" and told on canvas was by intent a partial view that omitted more than just the horrors of industrial warfare.13Louise Spence and Vinicius Navarro, Crafting Truth: Documentary Form and Meaning (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 11.

In the 1880s and 1890s, the Atlanta panorama, along with other Civil War battle paintings, provided an immensely popular attraction for audiences seeking to remember the military heroes and events of the 1860s while leaving much of the War out of the picture. No female figures are included on the huge canvas and a single Black male is depicted in civilian clothing far from the July 22, 1864, battle line. While the Battle of Atlanta, like most of the War's battles, pitted Union and Confederate armies against each other that were exclusively or almost entirely white men, enormous numbers of additional people participated in the War effort, including approximately 200,000 Black soldiers who served in the Federal army and countless women on both sides who were war matériel producers, foodstuff suppliers, health care workers, civil servants, undercover agents, and uniformed combatants.14William A. Dobak, Freedom By the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867 (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, United States Army, 2011), 501; Thavolia Glymph, The Women's Fight: The Civil War's Battles for Home, Freedom, and Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 10; Judith A. Giesberg, Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women's Politics in Transition (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000), 4. The awe-inspiring image of the Battle of Atlanta, like other heroic national narratives of the postbellum era, was a "selective celebration."15Stephanie McCurry, Women's War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil War (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019), 204. It venerated part of the past while marginalizing the significance of race and gender in wartime, in effect affirming a white, patriarchal social and political pecking order that prevailed as the Civil War and Reconstruction receded and the nineteenth century drew to a close. As historian William Blair emphasizes in an insightful analysis of sectional reconciliation and its political implications, reconciliation "involved defining nationalism, and the power relationships within it, resulting tragically in the exclusion of black people in the age of Jim Crow with white solidarity, in part, rallying around traditions in the form of Confederate commemorations."16William A. Blair, "Reconciliation as a Political Strategy: The United States After Its Civil War," in Reconciliation After Civil Wars: Global Perspectives, ed. Paul Quigley and James Hawdon (New York: Routledge, 2019), 217–231.

D. W. Griffith's notoriously racist The Birth of a Nation, which premiered in 1915, propagated a narrative account of the Civil War era in which white northerners and white southerners, one-time friends, become unwilling wartime foes but show mutual respect on the battlefield, reconcile after the War, reject the pursuit of Black political equality during Reconstruction, and—led by the Ku Klux Klan—forge a new nation to defend their "common Aryan birthright."17Robert Lang, ed. The Birth of a Nation: D. W. Griffith Director (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 134. As historian Leon Litwack observes, the motion picture "mesmerized and misled Americans, revealing the extraordinary power of the cinema to 'teach' history and to reflect and shape popular attitudes and stereotypes."18Leon F. Litwack, "The Birth of a Nation," in Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies, ed. Ted Mico, John Miller-Monson, and David Rubel (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995), 136–141. Griffith reused multiple images and tropes that debuted decades earlier and, aided by his filmmaking virtuosity, persisted long after his motion picture was first shown. The Birth of a Nation was a sensational visual spectacle that provided a blueprint for the Hollywood historical film.19Robert Burgoyne, The Hollywood Historical Film (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 26. "The panoramic battle scenes" were a "cinematic triumph," Michael Rogin notes in his appraisal of the film. Griffith's depictions were "distant, beautiful, and otherworldly."20Michael Rogin, "'The Sword Became a Flashing Vision': D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation," Representations 9 (Winter 1985): 150–195. Camera shots taken from a tower sixty feet above battling troops gave moviegoers a "sense of both wide scope and elevated historical perspective," as James Chandler points out.21Milton MacKaye, "The Birth of a Nation," Scribner's Magazine 102, no. 5 (1937): 40–46; James Chandler, "The Historical Novel Goes to Hollywood: Scott, Griffith, and Epic Film Today," in The Romantics and Us: Essays on Literature and Culture, ed. Gene W. Ruoff (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 237–273. The Birth of a Nation showed audiences how sprawling action sequences, crowd scenes, close ups, and star performances could be woven into a captivating feature-length narrative.22John Belton, American Cinema/American Culture (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 15; Bruce Chadwick, The Reel Civil War: Mythmaking in American Film (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 97. Griffith's creation also served as a forerunner to Gone With the Wind, which bore striking similarities to the earlier extravaganza in its production scale, fictionalized historical narrative, melodramatic mode, humiliating images of Black men and women, push back from civil rights activists, and runaway box office success.23Ruth Elizabeth Burks, "Gone With the Wind: Black and White in Technicolor," Quarterly Review of Film and Video 21, no. 1 (2004): 53–73; Jenny Barrett, Shooting the Civil War: Cinema, History and American National Identity (London: I.B. Tauris, 2009), 35; Ellen C. Scott, Cinema Civil Rights: Regulation, Repression, and Race in the Classical Hollywood Era (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 157–160.

The title of Griffith's film announced his animating concern: nation building. His message was that sectional reconciliation called for white solidarity, paramilitary acts of racial terror, and political and economic oppression of Black people. He deployed Lost Cause historical interpretations and perpetuated derogatory caricatures of Black and multiracial people that originated in the nineteenth century. The Birth of a Nation's "black marauders" and "mulatto villains," according to American Studies scholar Davarian Baldwin, helped justify "a so-called Southern Solution that stood as a form of governance, a system of labor management and land assessment, and an intellectual and cultural master trope."24Davarian L. Baldwin, "'I Will Build a Black Empire': The Birth of the Nation and the Specter of the New Negro," Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 14, no. 4 (2015): 599–603. The film's disparaging images prompted vigorous but largely unsuccessful protest campaigns waged by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other critics who sought to prevent exhibitions of the movie or censor its most vitriolic content.25Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation: A History of the "Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time" (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 129–170; Cara Caddoo, "The Birth of a Nation's Long Century," in The Birth of a Nation: The Cinematic Past in the Present, ed. Michael T. Martin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 33–45. Their efforts were blunted in part by President Woodrow Wilson, a former academic historian and past president of the American Historical Association, who tacitly endorsed The Birth of a Nation when he viewed it in the White House in February 1915.26Mark E. Benbow, "Birth of a Quotation: Woodrow Wilson and 'Like Writing History With Lightning,'" Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 9, no. 4 (2010): 509–533. For all of the film's white supremacist convictions and grotesque stereotypes, as cinema and media scholar Michael T. Martin emphasizes, Griffith's "filmic manifesto" reflected a prevailing historical interpretation of the Civil War era and a widely held belief early in the twentieth century that "race solidarity" was "the organizing principle for the nation's renewal."27Michael T. Martin, "Revisiting (As It Were) the 'Negro Problem' in The Birth of the Nation," in The Birth of a Nation: The Cinematic Past in the Present, ed. Michael T. Martin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 33–45.

The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama painting and The Birth of a Nation formed part of what anthropologist Benedict Anderson describes as a "vast pedagogical industry" that worked to convince Americans that the hostilities of 1861–65 were "a war between 'brothers' rather than between—as they briefly were—two sovereign nation-states."28Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Revised Edition (London: Verso, 2006), 201. The visual narratives invited their audiences to recognize what Anderson describes as "a deep, horizontal comradeship" that makes it possible for human beings, even without face-to-face contact, to imagine themselves as a single political community and participate in a common culture of nationalism.29Anderson, Imagined Communities, 6–7. The "figure of the soldier" is central to this storyline, serving as an embodiment of communal values and encouraging Americans, or at least most of the country's white population, to embrace a shared national identity.30Nicola Cooper and Martin J. Hurcombe, "The Figure of the Soldier," Journal of War and Culture Studies 2, no. 2 (2009): 103–104. Military memories conveyed by the Battle of Atlanta panorama and The Birth of a Nation acted as catalytic agents that contributed to a big burst of nationalistic energy.31Wilbur Zelinsky, Nation Into State: The Shifting Symbolic Foundations of American Nationalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 155. Linked compositionally and thematically, the cycloramic and cinematic renditions of the Civil War dramatized a version of nationalism that idealized sectional unity while dividing the population by race, ethnicity, and gender. The images provided popular accounts of a storied past and demonstrated Elisa Tamarkin's precept that "nationalism, as a form of feeling, an ideology, and a set of practices, works every bit as seriously at bringing some aspects of the outside in, as it does in keeping others out."32Elisa Tamarkin, Anglophilia: Deference, Devotion, and Antebellum America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), xxvi.

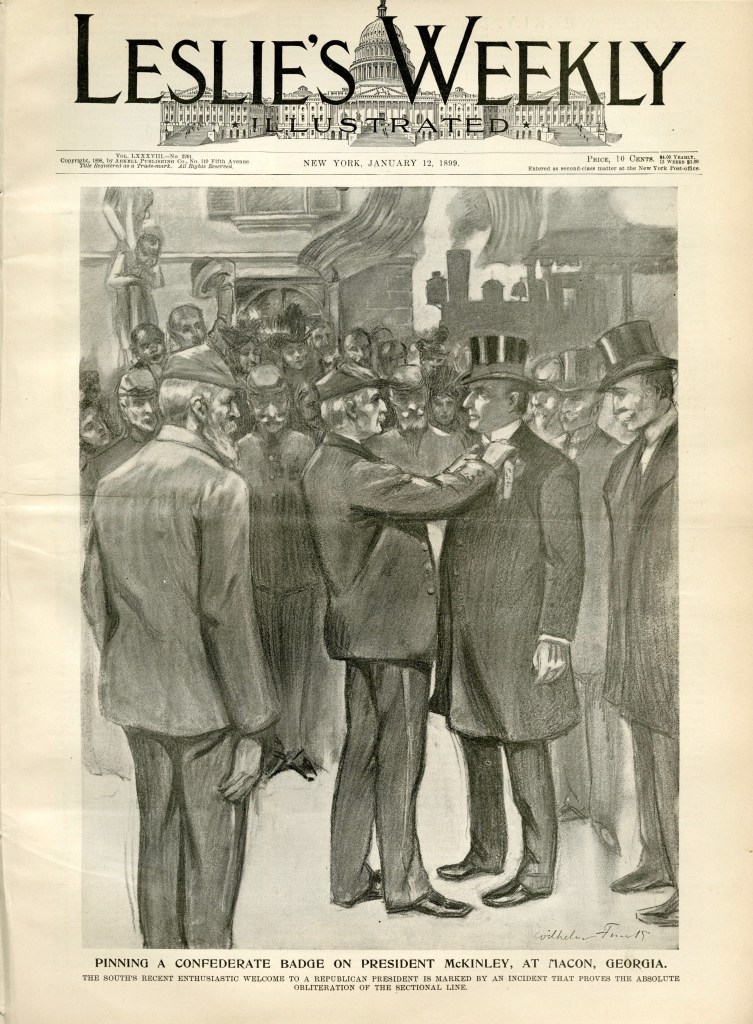

The nation that emerged in the fin-de-siècle US was more than "just an imagined community," as historian Charles Maier observes. It also was a "materialist and armed community," and the US military services forcefully demonstrated their reach in the last decade of the century.33David Armitage, Thomas Bender, Leslie Butler, Don H. Doyle, Susan-Mary Grant, Charles S. Maier, Jörg Nagler, Paul Quigley and Jay Sexton, "Interchange: Nationalism and Internationalism in the Era of the Civil War," Journal of American History 98, no. 2 (2011): 455–489. In December 1890, in the largest military operation since the Civil War, nearly a third of the nation's army descended on the Lakota in South Dakota and suppressed armed Indian resistance to white incursions. A confrontation between the Lakota and the US Seventh Cavalry near Wounded Knee Creek ended in the massacre of about 250 Native Americans.34Heather Cox Richardson, Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 11; Pekka Hämäläinen, Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), 378. In July 1894, the US Army again demonstrated its coercive power when nearly 2,000 troops, deployed to Chicago and joined by US marshals and local police, broke the Pullman strike.35Clayton D. Laurie and Ronald H. Cole, The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1877–1945 (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1997), 145. Once more the Seventh Cavalry went into action, this time on city streets, and striking workers were likened to the "savages" who the soldiers had slaughtered at Wounded Knee several years earlier.36Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 431. American military forces extended their reach beyond the nation's shores in 1898, when the US defeated Spain in a five-month war and took control of Spain's colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific.37A.G. Hopkins, American Empire: A Global History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018), 337. The war followed what American Studies scholar Matthew Frye Jacobson describes as a "protracted national discussion of what was demanded by America's rising national status as a world economic power—markets, bases, coaling stations, perhaps a canal."38Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 42. President William McKinley, in a December 1898 visit to Atlanta, hailed the victory over Spain as evidence that America had "proved itself invincible" and "will remain indivisible forevermore." Speaking at the municipal auditorium, McKinley proclaimed: "Under hostile fire on a foreign soil, fighting in a common cause, the memory of old disagreements has faded into history." In the spirit of sectional reconciliation, he proposed to another Atlanta audience that the national government begin honoring Confederate dead, whose public remembrances were limited at the time to commemorations by individual states and voluntary associations. "Every soldier's grave made during our unfortunate Civil War is a tribute to American valor," McKinley declared.39William McKinley, Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley, From March 1, 1897 to May 30, 1900 (New York: Doubleday & McClure, 1900), 159–160.

A surge in militant, white nationalism and the growing capacity of the US nation-state to project massive force were part of what historian C. A. Bayly describes as a vigorous, "global stirring of nationality" in the late nineteenth century. Bayly notes that despite a "hardening of boundaries between nation states and empires," people found "ways of linking, communicating with, and influencing each other across those boundaries."40C. A. Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 1780–1914 (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 199. Battle cults and cycloramic images of famous war scenes, which flourished first in France and Germany, were among the influential transnational exchanges.41Petty, "German Artists," 1. Profit-oriented European stock companies, geared to growing their international business, bankrolled panoramas of famous battles and shipped some of the most popular paintings across the Atlantic for showings in the US.42Fruitema and Zoetmulder, The Panorama Phenomenon, 28. These exports included a sprawling image of the Battle of Sedan, a major German victory in the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War, which was shown in New Orleans and Cincinnati in the mid-1880s after a successful debut in Frankfurt, Germany.43Peter C. Merrill, German-American Artists in Early Milwaukee: A Biographical Dictionary (Madison, WI: Friends of the Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies, 1997), 64; Kevin M. Kurdylo, "Investigating an International Treasure: The Diaries of Panorama Artist F. W. Heine," Max Kade Institute Friends Newsletter 17, no. 4 (2008): 7; Beth Irwin Lewis, Art for All?: The Collision of Modern Art and the Public in Late Nineteenth Century Germany (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 34. Louis Braun, a Munich art professor who led the team that produced the Sedan painting, was known for creating battle panoramas with strong nationalistic overtones.44Bernard Comment, The Painted Panorama (New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1999), 164.

One of Braun's acolytes was August Lohr, an Austrian painter who worked with him in Munich on the Sedan project and other battle panoramas before moving to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1885 to help entrepreneur William Wehner launch the American Panorama Company.45Merrill, German-American Artists, 64. In a prime example of what historian Antje Petty describes as a "wholesale transfer of European panorama art and craft" to the US, Wehner and Lohr persuaded a group of well-known painters from art schools in German-speaking countries to join them in Milwaukee and produce Civil War cyclorama paintings.46Petty, "German Artists," 3; Merrill, German-American Artists, xi. Their first recruit was Friedrich Heine, an experienced battle painter and former war correspondent and illustrator from Dresden, Germany, who joined his long-time friend Lohr as codirector of panorama production in Wehner's studio.47"The Artists of Atlanta: The Men Who Have Painted the Panorama," Battle of Atlanta Monthly 1, no. 1 (October 1, 1886): 1. Specialists in painting landscapes, human figures, and animals comprised the rest of the artistic team.48Manual of the Cyclorama of the Battle of Atlanta (Detroit, MI: Detroit Cyclorama Company, 1887), 1. Together with Lohr and Heine they painted both versions of the Battle of Atlanta cyclorama panorama.

Wehner and his company's artistic team placed a high priority on creating a historically accurate representation of the battle. Promotional materials and souvenir brochures that described the paintings emphasized their verisimilitude and educational value. Old soldiers often visited battle panoramas with family and friends and pointed out where and how they contributed to their side's cause.49Comment, Painted Panorama, 129. The slightest inaccuracy detected by discerning panorama spectators, such as veterans or other eyewitnesses to the battle, would collide with claims that viewers would see a faithful reproduction of the battlefield and combat action. To help meet the paying public's expectations for authenticity, Wehner and his lead artists enlisted the expert assistance of Theodore R. Davis, a former Civil War sketch artist for Harpers Weekly who had witnessed the battle from General William T. Sherman's field headquarters.50Wilbur G. Kurtz, The Atlanta Cyclorama: The Story of the Famed Battle of Atlanta (Atlanta, GA: City of Atlanta, 1954), 25. Davis shared his recollections of the fighting, and he helped the panorama team gather additional information from sketches, photographs, military maps, written records, and eyewitnesses. In the summer and fall of 1885, he accompanied the team on a site visit to Atlanta and its eastern suburban neighborhoods, where the battle was fought.51Manual of the Cyclorama, 2. Several artists completed sketches of the battle area from a forty-foot high wooden tower near the site of the Troup Hurt House and close to the Georgia Railroad, where intense combat action swirled on July 22, 1864. The painters' elevated perch provided an unobstructed view of the proximal battleground landmarks and the surrounding terrain. According to Wehner, local citizens "were astonished to find that their brethren of the North were in possession of facts that enabled them to clearly define every circumstance of the battlefield." Former Confederate officers, Wehner reported, appreciated the efforts to make a "historical painting" and took "special pains to verify statements concerning their positions."52Manual of the Cyclorama, 2.

By design, the geographic spot that the Milwaukee-based artists chose for their aerial studies of the Atlanta battle area corresponded to the central vantage point in the cyclorama rotundas where their circular paintings were subsequently exhibited. This compositional strategy enabled the painters to transfer their outward radiating, 360-degree sightlines and elevated perspective to panorama audiences.53Graham F. Watts, "'The Smell O' These Dead Horses': The Toronto Cyclorama and the Illusion of Reality," University of Toronto Quarterly 74, no. 4 (2005): 964–970. As a result, spectators standing in the middle of a rotunda's raised platform commanded sweeping views of each battlefield event depicted on canvas. Multiple military actions, represented as though they were simultaneous and instantaneous, created the impression of a dramatic continuum across the vast Atlanta battlegrounds.54Gillian Russell, The Theatres of War: Performance, Politics, and Society, 1793–1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 76–77; Mary A. Favret, War at a Distance: Romanticism and the Making of Modern Wartime (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 216.

Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama Painting

1: Confederate Attack

At 4:30 p.m., Confederate troops under Brigadier General Arthur Manigault and other advancing brigades moved out from behind Atlanta's defenses and spearheaded an attack that poured through a weakness in the US 15th Army Corps line at the Georgia Railroad, overwhelmed their entrenched foes, and seized the DeGress Battery, shown near the Troup Hurt House, and other artillery pieces. This dramatic action threatened to turn the battle into a rout. However, the sudden momentum shift in the Confederate's favor was short-lived. US Army field officers marshaled their forces and led a sweeping counterattack, shown in the painting as blue-clad soldiers charging toward the Troup Hurt house and surging elsewhere to restore their broken infantry line.

2: Logan Rallies the US Troops

Following the break in the US Army's 15th Corps line, Major General John A. Logan, hat in hand and aboard his horse Slasher, is shown galloping toward the battlefront, followed by his staff and a hatless Captain Francis DeGress, whose battery Confederate infantry had captured. Earlier in the afternoon, Logan succeeded Major General James B. McPherson, killed in action, as commander of the Army of the Tennessee, the principal US Army in the Battle of Atlanta. When Confederate attackers broke the 15th Army Corps line, swift action by Logan and other US Army field officers repulsed the Confederate assault and averted a battlefield disaster for the Union army. In his new role as army commander, Logan marshaled reinforcements, summoned artillery support, and rode along the lines of his counterattacking troops, exhorting them with the rallying cry of "McPherson and Revenge."

3: US Army Counterattack

US Army Brigadier General Joseph Lightburn, shown on his chestnut-colored horse near the front of his brigade, led his soldiers towards a clash with Confederate attackers who, a little more than an hour earlier, had poked a big hole in the US Army 15th Corps line and threatened more serious damage. Lightburn's brigade was part of a concerted assault in which three Divisions of the 15th Army Corps surged forward, threw back the Confederates, and restored the Union line where it had been broken. The counterattacking infantry gained ground quickly, supported by artillery fire directed in part by Major General William T. Sherman, commander of the US forces advancing on Atlanta. However, Sherman's battlefield role was limited. He appears in the painting as a distant figure on horseback in front of his field headquarters at the Augustus Hurt house, observing combat action three quarters of a mile away from his perch.

4: Fighting For the High Ground

The most intense fighting in the Battle of Atlanta was at Bald Hill, a broad expanse of high ground, largely cleared for farming, which provided a commanding position for the army that controlled it. The day before the battle, US Army Brigadier General Mortimer Leggett's Division captured the hill—subsequently renamed Leggett's Hill—from Confederate defenders. During the battle, successive waves of Confederate attacks beginning in the early afternoon hit Leggett's Division and other US Army infantry units defending the hill, thinning their ranks and forcing them to give ground. The painting depicts Confederate Major Carter Stevenson's Division in a late afternoon assault, charging across the open ground toward Leggett's troops posted along the tree line. Stevenson's attack failed and ferocious fighting at Bald Hill continued until dark, when the Confederates fell back and the US Army reclaimed the ground it had yielded.

5: Battling Along the Tracks

Confederate troops charged toward the Troup Hurt House via a short section of the Georgia Railroad that lay below ground level at a knoll. This railroad cut, shown in the painting after the attack, illustrates the tactical, battlefield importance of rail lines and trackwork. Railroads also had a larger strategic significance. The Battle of Atlanta occurred where and when it did because the US Army targeted a vital railway. At battle's end, the Union Army had reasserted its control of the Georgia Railroad, fended off its foes, and emerged with its biggest victory in the Atlanta Campaign. In subsequent clashes, US troops severed the city's remaining railways, after which the Confederate Army left Atlanta on September 1 and Union troops entered the city the next day. Atlanta's fall was a major Civil War turning point. It contributed to Abraham Lincoln's re-election in November 1864, the Union's eventual restoration, and slavery's end.

Making a Spectacle of Nationalism

Theodore R. Davis explained in an 1886 article, "How A Great Battle Panorama is Made," that as soon as cyclorama visitors reached the central viewing platform they would seemingly "stand in the midst of a real battle."55Theodore R. Davis, "How a Great Battle Panorama is Made," St. Nicholas 14, no. 2 (1886): 99–112. The simulated, bird's-eye view of the Battle of Atlanta placed audiences just behind the Federal Army of the Tennessee's generals, junior officers, and soldiers and closest to where a hard charging Confederate brigade had broken the Union infantry line at the Troup Hurt House and Georgia Railroad. Federal Major General John A. Logan is shown galloping toward the battlefront, spurring on his troops as they surge forward in a counteroffensive that restores their line and retakes a famed group of cannons, the DeGress battery, that temporarily changed hands. Logan's vivid likeness and his pictorial prominence far surpass the representation of his commanding officer, General William T. Sherman, who is barely visible on a high hill above the battlefield, observing the action below from the grounds of his field headquarters. The Confederate army's commander, John Bell Hood, does not appear in the Battle of Atlanta painting.

When the Battle of Atlanta panorama premiered in Minneapolis in July 1886, promotional placards with a tagline of "Logan to the Front!" depicted the general known as Black Jack in full gallop, his raven mane and handlebar moustache flowing as he held out his broad-brimmed hat at arm's length to encourage his surging troops. "Logan's Great Battle" was the advertising pitch in a Detroit newspaper when a copy of the "most reliable Panorama on earth" opened at that city's cyclorama rotunda in February 1887.56Advertisement, Detroit Free Press, February 27, 1887, 3. Black Jack's panoramic image and the accompanying promotional publicity burnished his reputation as one of the most successful Civil War generals on either side who did not attend West Point. He was the consummate Volunteer Soldier of America.57Stuart McConnell, Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic 1865–1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 193. Logan parlayed his military fame and his close identification with the winning side into a long, postwar career as a powerful and steadfastly partisan Illinois Republican who served in the US House and Senate and was a prime mover of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the largest Union veterans group. Logan's most enduring act as the GAR's commander-in-chief was his order in 1868 calling for all GAR posts to set aside May 30 as Memorial Day.58James P. Jones, John A. Logan: Stalwart Republican From Illinois (Tallahassee: Florida State University Press, 1982), 19. His ambitions for higher political office culminated in the Republican vice-presidential nomination in 1884, when he ran on the losing ticket headed by James G. Blaine. At the time of Logan's unexpected death at age sixty in December 1886, he was a leading contender for his party's top spot in the next presidential election. In the words of Logan's twentieth-century biographer James P. Jones, Black Jack "fought in the political arena with the ferocity he exhibited on the battlefield."59Jones, John A. Logan, 227. Yet because of his personal financial straits, the oft-repeated story that Logan commissioned the Battle of Atlanta painting to further his political ambitions is almost certainly apocryphal.

The panorama and its initial publicity in midwestern cities featured Logan's rousing leadership in the thick of battle. Although partial to the Union army's famous general and the troops he spurred on, the painting celebrated soldiers on both sides and their fervent commitments to their respective military missions. Each army faced a formidable foe, and the vivid display of combat mettle by clashing Federal and Confederate forces added luster to their individual martial reputations. This pictorial salute to the rank and file appealed to many white Americans who, beginning in the 1880s, avidly sought detailed visual and text accounts of Civil War military events and heroics but also eagerly put aside divisive sectional issues such as slavery, secession, and emancipation.60Timothy P. Caron, "'How Changeable Are the Events of War': National Reconciliation in the Century Magazine's 'Battles and Leaders of the Civil War,'" American Periodicals:A Journal of History and Criticism 16, no. 2 (2006): 151–171. As a broadening but still incomplete embrace of "reconciliation through recollection" gathered national momentum, according to historian David Blight, the ideological divides of the war faded from view.61Blight, Race and Reunion, 164, 217. The upshot was that "nationalism displaced the emancipatory meaning of the war," writes Thomas Bender in A Nation Among Nations: America's Place in World History. The hagiographic treatment of battle-tested Union and Confederate veterans instrumentalized the solider as the embodiment of the nation. As Bender explains: "All were brave; all fought for what they believed. All the old soldiers were heroes."62Thomas Bender, A Nation Among Nations: America's Place in World History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), 180.

The drama of a heroic commander was a central element in the Battle of Atlanta painting: "Logan to the Front!" However, the even bigger picture was the panorama's portrayal of courageous soldiers amassed against each other in a powerful display of collective battlefield moxie. The Gettysburg painting, like its Atlanta counterpart, combined the "energy and the bravery of the many" with the "drama of the hero."63Peter Paret, Imagined Battles: Reflections of War in European Art (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 66. No Black soldiers fought at Gettysburg, but several Black male laborers are depicted on the Union side in the panorama.64Brenneman and Boardman, Gettysburg Cyclorama, 188. The absence of a Black combat role in the battle meant that in the "telling and retelling of events," as historian Kenneth Nivison notes, "Gettysburg became . . . an icon of selective remembrance."65Kenneth Nivison, "Fields of Mighty Memory: Gettysburg and the Americanization of the Civil War," in The Battlefield and Beyond: Essays on the American Civil War, ed. Clayton E. Jewett (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012), 291–309. The sprawling tableaux commemorated the most famous battle of the Civil War by hailing the bravery of white soldiers on both sides, The panorama also paid monument-like homage to a heroic general on horseback, foreshadowing his postbellum political career.66Benjamin T. Arrington, The Last Lincoln Republican: The Presidential Election of 1880 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2020), 110–112. Premiering in Chicago in 1883, three years before the Atlanta painting opened in Minneapolis, the visual narrative showed Major General Winfield Scott Hancock astride his horse, urging his infantry and artillery forward after their line was attacked by Confederate troops. The bold assault on the Union center, part of what is now known as Pickett's Charge on day three of the battle—the High Water Mark of the Confederacy—was met with a devastating response, and the entire attack failed in the Civil War's most hallowed combat encounter. After the war, Hancock, who was severely wounded at Gettysburg, capitalized on his military fame to remain a heralded public figure and, like Logan, pursue national office. In 1880 Hancock was narrowly defeated when he ran as the Democratic party's candidate for President. The Union war hero carried all the former slave states but only a single northern state, New Jersey, in his presidential lost cause.67Charles W. Calhoun, From the Bloody Shirt to Full Dinner Pail: The Transformation of Politics and Governance in the Gilded Age (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 75.

When the Atlanta and Gettysburg panoramas circulated from city to city, they offered a popular commemorative formula—"two brands of the same valor"—that attracted an enormous number of spectators.68Nivison, "Fields of Mighty Memory," 292. Over 286,000 paying customers viewed the Atlanta painting during its approximately eighteen-month Detroit run.69"The Cyclorama," Detroit Free Press, October 28, 1888, 20. Notwithstanding "many cracks in the plaster of national reunification," to borrow historian John R. Neff's succinct description, the Civil War combatants in the paintings exemplified the "deep horizontal comradeship" that enabled many late nineteenth-century white Americans to imagine themselves as members of a single community.70John R. Neff, Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005), 205. The soldiers are portrayed as "the model of manly character," which historian Kristin Hoganson describes as a set of traits—including loyalty to one's fellows, fearlessness, and a calibrated combination of belligerence and chivalry—that elicited popular acclaim for veterans of both sides.71Kristin L. Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 24. The combatants shown in the cyclorama paintings function as a "point of origin" for the larger imagined brotherhood, as evidenced by the broad political authority conferred on Civil War veterans in the postbellum years. "The soldier is a foundational figure," Nicola Cooper and Martin J. Hurcombe explain in their interpretation of the warrior's role in society. Cooper and Hurcombe add that "he" "is central to the history, self-image, and identity of the nation."72Cooper and Hurcombe, "Figure of the Soldier," 103.

After the War, according to Hoganson, a "military style of politics" emerged from "the idea that the state rested ultimately on soldier-citizens," and even nonveterans who vied for political office cited "the military valor of men from their class, race, region, or ethnicity or their own soldierly attributes." Hoganson emphasizes that this style of politics "made American political culture more inclusive for men" while carrying with it "exclusionary implications for women."73Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood, 25–26. And, just as celebratory memories of male military service sidelined full citizenship for females, selective commemorations that omitted or minimized the wartime roles of Black Americans contributed to mainstream indifference or outright hostility toward racial equality.74Cecilia E. O'Leary, To Die For: The Paradox of American Patriotism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 129. In the waning years of the nineteenth century, Martin A. Berger observes in Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture, whites harboring racially discriminatory attitudes and beliefs unselfconsciously transferred their values onto the images around them. The art of exclusion was among the creative ways that "silently reinforced" Jim Crow practices, which denigrated and did violence to Black people for years to come.75Martin A. Berger, Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 173–174.

The Civil War battle scenes on sprawling paintings expressed the increasingly dominant narrative of national belonging that encouraged audiences to transcend sectionalism and coalesce around a common white identity.76Jimmy L. Bryan, "Introduction," in The Martial Imagination: Cultural Aspects of American Warfare, ed. Jimmy L. Bryan (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2013), 1–11. Vivid, smaller-scale versions of this panoramic theme, included on the canvases themselves or accompanying souvenir programs, cast a spotlight on comradery and common Americanness. In their painting, the Atlanta panorama artists foreground a poignant depiction of a Union warrior sharing his canteen with a wounded Confederate soldier. This image of battlefield magnanimity amid the chaos of combat illustrated the possibilities for intersectional, postwar harmony. The emotionally compelling connection between erstwhile enemies, legendarily siblings who rediscovered each other under dire circumstances, represented in a condensed, visual form the four years-long "brother's war" and the opportunity for reunion of a national "family." Canteen sharing with foes or friendly troops suggested a common humanity or, in other words, "white male unity," as historian Lauren K. Thompson points out in her study of soldier fraternization during the Civil War.77Lauren K. Thompson, Friendly Enemies: Soldier Fraternization throughout the Civil War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 154. In another emblematic and evocative image, a souvenir program for the Gettysburg cyclorama depicted soldiers from the two sides clasping hands. This oft repeated symbol of mutual respect and sectional affinity expressed in a single gesture an underlying bond between white, wartime opponents that gained new cache in the century's final years. In the century to come, the images of canteen sharing and hands clasping also served as visual and thematic through-lines to D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation and other cinematic Civil War narratives.

At the peak of the cyclorama vogue in the US, four versions of the Gettysburg panorama and two copies of the Atlanta painting circulated simultaneously from city to city.78"Watching Pickett's Charge," New York Times, March 5, 1887, 3; "The Battle of Atlanta Today," Detroit Free Press, February 26, 1887, 5; Battle of Atlanta advertisement, St. Paul Daily Globe, March 8, 1887, 3. They toured at the same time as other Civil War battle panoramas, and the intense competition for viewers prompted promoters to take down the gigantic paintings and replace them with new ones at a rapid pace.79Oettermann, Panorama, 239. In a span of six years, the Battle of Atlanta panorama initially exhibited in Minneapolis also was shown in Indianapolis, Chattanooga, and Atlanta, where it has remained on display almost without interruption since 1892. As impresarios moved the panoramas from one city to another, they sometimes altered images to increase their appeal to a local audience. Paul Atkinson, an entrepreneur who bought the Battle of Atlanta panorama in 1890, prepared it for exhibition in Chattanooga by commissioning an artist to convert a group of Confederate prisoners to retreating Union soldiers. Atkinson recalled that when the alteration was completed, "he had a bunch of Yankees running like the mischief."80Alma H. Jamison, "The Cyclorama of the Battle of Atlanta," The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, no. 10, July 1937, 58–75. The ruse continued when Atkinson moved the painting to its final stop, where the Atlanta Constitution heralded the attraction as the only Civil War battle panorama "in which confederate soldiers are shown in the moment of victory." The newspaper reported that "Mr. Atkinson, who is always on the stage, will give away any information desired in regard to the battle, and he is remarkably well up on his history, and tells many interesting stories of incidents in the fight."81"Right at Home," Atlanta Constitution, February 23, 1892, 9.

Try as they might, promoters could not keep the cyclorama boom going, and the paintings fell out of fashion at the turn of the century.82Comment, Painted Panorama, 257. They "acquired a certain aura of quaintness," according to historian Angela Miller.83Miller, "Panorama," 58. An early indication of the downturn was the low sales price for the Battle of Atlanta painting when it changed hands in its namesake city eighteen months after its opening. "It Went for a Song," the Atlanta Constitution announced, fetching just $1,110.84"It Went for A Song," Atlanta Constitution, August 9, 1893, 7. The panorama trade was a risky business, and a painting that did not make a profit in one city could leave promoters without the means to dismantle and move the canvas to a new location. It might be left to languish where it was last displayed. Yet some entrepreneurs continued to invest in cyclorama paintings until their commercial appeal declined precipitously.85Fruitema and Zoetmulder, The Panorama Phenomenon, 28. The mammoth canvases were particularly vulnerable to rapidly increasing competition from motion pictures. Movies were more easily distributed and displayed, offered an immersive viewing experience, and surpassed cyclorama paintings by adding photographic realism and movement to the mix.86Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion: Media Archeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 363; Miller, "Emergence of the Spectacular," 41–42, 58. Still, the rapidly ascendent medium inherited important elements from its predecessor. Long shots of landscapes combined with close-ups of human figures and a seamless blending of different scenes into a single composition linked the two media to a common visual grammar.87Griffiths, "'Shivers Down Your Spine,'" 21. During cinema's early years, from 1894 through approximately 1908, panoramic shots of natural or human-made wonders were among the most popular subjects.88Tom Gunning, D. W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film: The Early Years at Biograph (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 216. "Film was quick to embrace the panorama," according to media scholar William Uricchio, who cites evidence (possibly incomplete) that in the first years of motion pictures "panorama" or "panoramic views'" were the leading copyright entry recorded for movies in the US.89William Uricchio, "A 'Proper Point of View': The Panorama and Some of Its Early Media Iterations," in Early Popular Visual Culture 9, no. 3 (2011): 225–238. However, films at that time were too short, some less than a minute, to tell the story of famous battles that had been depicted so vividly in cyclorama paintings.90André Gaudreault and Tom Gunning, "Introduction" in American Cinema, 1890–1909: Themes and Variations, ed. André Gaudreault (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 1–21. Filmmakers concentrated on exhibiting brief, attention-grabbing visual novelties and snippets of sensational events that comprised what film historian Tom Gunning describes as the "cinema of attractions."91Gunning, D. W. Griffith, 6.

D. W. Griffith was at the forefront of the transition from short movies that "show" to longer films that "tell." His work, beginning with his directorial debut in 1908, typified what Gunning refers to as the "cinema of narrative integration."92Gunning, D. W. Griffith, 6. Griffith used a variety of innovative filmmaking techniques to narrate events and develop his characters. His methods included displaying two or more simultaneous events in rapid succession to connect story lines, panoramic shots to depict scenes of expansive action, and close-ups to draw attention to individual performers. Griffith did not introduce these techniques, but he experimented with them, and he was among the first American directors to anticipate the popular appeal of multiple-reel, feature-length films.93Stokes, D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, 74–77; Burgoyne, The Hollywood Historical Film, 25. He also recognized the Civil War's cinematic potential, which increased as the semicentennial of the War approached and then peaked as veterans' reunions and other commemorative activities marked the fiftieth anniversary of major events.94Robert Jackson, "The Celluloid War Before The Birth: Race and History in Early American Film," in American Cinema and the Southern Imaginary, ed. Deborah Barker (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011): 27–51; David W. Blight, "Quarrel Forgotten or a Revolution Remembered? Reunion and Race in the Memory of the Civil War, 1875–1913," in Union and Emancipation: Essays on Politics and Race in the Civil War Era, ed. David W. Blight and Brooks D. Simpson (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1997): 151–217. Between 1908 and 1915, Griffith directed twelve Civil War movies, culminating in his three-hour epic The Birth of a Nation, which was made to celebrate the golden anniversary of the War's end.95Paul C. Spehr, The Civil War in Motion Pictures: A Bibliography of Films Produced in the United States Since 1897 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1961); Belton, American Cinema/American Culture, 125. When it was released in February 1915, according to Leon Litwack, "the motion picture as art, propaganda, and entertainment came of age."96Litwack, "The Birth of a Nation," 136. For the newly revived Ku Klux Klan, the movie's release and distribution were a boon for membership recruitment.97Nancy MacLean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 13.

Griffith and movie producer Roy Aitken led a promotional campaign for The Birth of a Nation that film historian Bruce Chadwick describes as unprecedented in scope. They hired public relations director Ted Mitchell, and "the trio seemed to think of everything," according to Chadwick.98Bruce Chadwick, The Reel Civil War, 130. Advertising blitzes for the motion picture began two weeks before the film arrived in towns on its national tour. Publicity managers heralded the film's opening with parades that featured performers dressed as Klansmen. Promotional materials included widely distributed postcards that displayed Union and Confederate soldiers clasping hands as they held their rifles at rest. Movie programs sold at theaters listed the film's cast and described how Griffith made his motion picture extravaganza. Aided by President Woodrow Wilson's implicit endorsement and despite vigorous protests by the NAACP, the film played to packed theaters nationwide and reaped enormous profits. It produced more than $60 million in revenue in its first run, and its biggest box office business was in northern and western cities, where, according to historian Gary Gallagher, "patrons likely were dazzled by Griffith's technical skill and masterful staging and little bothered by his racism."99Richard Schickel, D. W. Griffith: An American Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984), 281; Chadwick, The Reel Civil War, 132; Gary W. Gallagher Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 45.

Griffith tells his version of the Civil War and Reconstruction by recounting the epic saga of two fictional, white families, the southern Camerons and the northern Stonemans. The two clans represent the temporarily divided sides in the "house of the nation," which, in Griffith's melodramatic tale, were destined to reunite and reassert white supremacy after a cataclysmic war and a tragic, postwar era of Black domination.100Elisabeth Bronfen, Specters of War: Hollywood's Engagement With Military Conflict (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012): 26; Hernan Vera and Andrew Gordon, "Sincere Fictions of the White Self in the American Cinema, The Divided White Self in Civil War Films" in Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness, ed. Daniel Bernardi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001): 263–280. The hero is Ben Cameron, who serves as a Confederate army colonel during the movie's first half and then forms and leads the Ku Klux Klan in the immediate postwar years, which are covered in the film's second half. Griffith's Civil War segment repeats images and themes that appeared thirty years earlier in cyclorama battle paintings, including a canteen-sharing moment in which Ben Cameron provides succor to a Union soldier. More broadly, Griffith followed the panoramic formula by combining the "drama of the hero" and the "energy and the bravery of the many" into a unifying story that transformed America's bloodiest conflict into a "brother's war." Sweeping battle scenes shot from afar blur the distinction between the opposing sides. Dramatic close-ups of hand-to-hand combat and striking displays of selfless acts provide evidence of bilateral gallantry. The causes for which the Union and Confederate armies fought do not enter the picture. "As important as the Civil War was," historian Stephen Weinberger explains, "Griffith does not present it as a conflict between right and wrong or good and evil."101Stephen Weinberger, "Austin Stoneman: The Birth of a Nation's American Tragic Hero," Early Popular Visual Culture 10, no. 3 (2012): 211–225.

To a large extent, the cycloramic-cinematic parallels end when The Birth of a Nation picks up the story of Reconstruction in its second half. Griffith presents the postwar period as a contest between right and wrong, and the combatants are as markedly different, literally black and white, as the Civil War contestants were similar.102Ibid., 213. Black people and women take center stage, a notable contrast with their nearly complete absence from the cyclorama paintings. Griffith portrays Black characters as "incapable of self-government or self-control."103Barrett, Shooting the Civil War, 130. His white women are vulnerable and victimized; they must be protected and rescued by chivalrous white heroes. Ben Cameron's leadership of the Ku Klux Klan's vigilante violence against "black villains," including a lynching, is a portrayed as a legitimate exercise of power in defense of "white women in distress."104Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009): 153. Cameron is a "hero on horseback," Griffith suggests, the leader of an invisible army whose bravura performance and legacy equal or surpass the achievements of the generals who appear in Civil War panoramas. In Griffith's telling, Ben Cameron is a foundational figure around whom the forces of a divided nation coalesce, just as his own family reconciles with their northern counterparts in pursuit of a common cause. Cameron's paramilitary conquests are followed by a celebratory Ku Klux Klan parade and two Cameron-Stoneman weddings, which strengthen the bond between the fictional families and serve as Griffith's allegorical summation of how white southerners and white northerners reunite and give birth to a nation. In the movie's final moments, a title card appears that cunningly and ironically transforms a wartime rallying cry for the Union—which originated with Daniel Webster's famous 1830 Senate oration—into a white nationalist vision of American civilization predicated on racial purity and hierarchy: "Liberty and union, one and inseparable, now and forever!"105Christopher Childers, The Webster-Hayne Debate: Defining Nationhood in the Early American Republic (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 112–113; Steven R. Boyd, Patriotic Envelopes of the Civil War: Iconography of Union and Confederate Covers (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010), 81.

The history of militarized commemorative culture in the US is lengthy. It began long before the Battle of Atlanta panorama circulated from city to city, and it endures long after The Birth of a Nation's multiple runs in movie theaters nationwide. From the revolutionary era to the present day, war stories—including visual narratives—have helped spawn American nationalism and shape the national polity.106Sarah J. Purcell, Sealed With Blood: War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 6–7; Gerald R. Webster, "American Nationalism, the Flag, and the Invasion of Iraq," The Geographical Review 101, no. 1 (2011): 1–18. The US experience is not unique; military commemorations, even for lost causes, have spurred nationalistic commitments in many places and eras. War is unique; it has a singular capacity to inculcate or invigorate links between large numbers of people who would otherwise have little reason to cohere into a national "community" or continue to participate in one.107Raymond Haberski, "War and American Thought: Finding a Nation Through Killing and Dying," in American Labyrinth: Intellectual History for Complicated Times, ed. Raymond Haberski and Andrew Hartman (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 183–197. During the nineteenth century, as described by historian Susan-Mary Grant, "in Europe as in the United States, nations increasingly came to understand themselves and trace their origins through the wars they had fought and the military leaders [who] exemplified their particular brand of nationalism." Artistic and literary representations of battles and heroes expressed the national stories.108Susan Mary-Grant, "Constructing a Commemorative Culture: American Veterans and Memorialization from Valley Forge to Vietnam," Journal of War and Culture Studies 4, no. 3 (2011): 305–322. The Atlanta panorama and The Birth of a Nation helped shape that story in the US by providing popular forms of a "spectacle pedagogy" that taught many Americans how to see and think nationalistically about the Civil War.109Charles R. Garoian and Yvonne M. Gaudelius, "The Spectacle of Visual Culture," Studies in Art Education 45, no. 4 (2004): 298–312. The shared viewing experience and famous military subjects of these vast pictorial spectacles served to instill and express a national identity, albeit one that excluded many people.

The cycloramic and cinematic wartime commemorations helped communicate who qualified in post-Civil War America for full membership in the nation and who did not. As nationalistic spectacles, the two visual narratives brought some aspects of the outside in while keeping others out. However, the painting and the movie differed in how they excluded large numbers of people from the national picture. While the Battle of Atlanta panorama displayed indifference, The Birth of a Nation showcased violent intolerance. In the years between their premiere showings, over a span of three decades, a militarized and racialized nationalism gained increasing traction in the US before tightening its grip even more during and after World War I.110O'Leary, To Die For, 242–245. One hundred years later, the extent to which that grasp continues its hold on the country is an open question, with some indications that a more inclusive American nationalism is fitfully gaining strength or at least proponents. Still, plenty of evidence points to the enduring power of an exclusive and militant nationalism, traceable to antecedents in the post-Civil War era and taking a toll today in myriad ways, from endless wars to mass deportations, targeted voter suppression, police militarization, extrajudicial killings of Black men and women, xenophobic terror attacks, and demagogic political leaders who use false narratives and racist rhetoric to incite nativist violence.

About the Author

Daniel A. Pollock, MD, is a medical epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, where he leads a unit responsible for national surveillance of healthcare-associated infections and COVID-19's impact on healthcare facilities. Since arriving in Atlanta in 1984, he has pursued an independent scholarly interest in the city's Civil War history, and he has conducted nearly 200 tours of Battle of Atlanta sites.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to colleagues in the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS) and the Southern Spaces editorial staff, with special thanks to Wayne H. Morse, Jr., Allen Tullos, Kayla Shipp, Jay Varner, Steve Bransford, and Michael Page. Thank you as well to Tesla Cariani at ECDS and Paige Knight at Emory University Libraries for their assistance. Use of the Battle of Atlanta panorama images in this monograph was made possible through ECDS's partnership with the Atlanta History Center (AHC). Thanks to Gordon Jones and Jesse Garbowski at AHC for their lead roles in that partnership.

Recommended Resources

Text

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Revised Edition. London: Verso, 2006.

Blair, William A. "Reconciliation as a Political Strategy: The United States After Its Civil War." In Reconciliation After Civil Wars: Global Perspectives. Edited by Paul Quigley and James Hawdon, 217–231. London: Routledge, 2019.

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Brenneman, Chris and Sue Boardman. The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beattie, 2015.

Gannon, Barbara A. Americans Remember Their Civil War. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2017.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. The Stony Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow. New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

Griffiths, Alison. "'Shivers Down Your Spine': Panoramas and the Origins of Cinematic Reenactment." Screen 44, no. 1 (2003): 1–37.

Hess, Earl J. Battle for Atlanta: Tactics, Terrain, and Trenches in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Janney, Caroline E. Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Judt, Daniel. "Cyclorama: an Atlanta Monument." Southern Cultures 23, no. 2 (2017): 23–48.

Linn-Tynen, Erin. "Reclaiming the Past as a Matter of Social Justice: African American Heritage, Representation and Identity in the United States." In Critical Perspectives on Cultural Memory and Heritage: Construction, Transformation, and Destruction. Edited by Veysel Apaydin, 255–268. London: UCL Press, 2020.

Marten, James, and Caroline E. Janney, eds. Buying and Selling Civil War Memory in Gilded Age America. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021.

Martin, Michael T., ed. The Birth of a Nation: The Cinematic Past in the Present. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019.

McPherson, James M. This Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Miller, Angela. "The Panorama, the Cinema, and the Emergence of the Spectacular." Wide Angle 18, no. 2 (1996): 35–69.

Mohr, Clarence L. "The Atlanta Campaign and the African American Experience in Civil War Georgia." In Inside the Confederate Nation: Essays in Honor of Emory M. Thomas. Edited by Lesley J. Gordon and John C. Inscoe, 272–294. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Oettermann, Stephan. The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium. New York: Zone Books, 1997.

O'Leary, Cecilia E. To Die For: The Paradox of American Patriotism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999

Stokes, Melvyn. D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation: A History of the "Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time." New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Web

"The Battle of Atlanta: History and Remembrance." Take a virtual, guided tour of the Battle of Atlanta with Daniel Pollock. May 2014. https://battle-of-atlanta.opentour.site/tours.

"Cyclorama: The Big Picture." Atlanta History Center. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/exhibitions/cyclorama/.

"Gettysburg Cyclorama." Gettysburg Foundation. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://www.gettysburgfoundation.org/gettysburg-cyclorama/.

Hitt, Jack. "Atlanta's Famed Cyclorama Will Tell the Truth about the Civil War Once Again." Smithsonian Magazine. December 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/atlanta-famed-cyclorama-tell-truth-civil-war-once-again-180970715/.

"Indianapolis Cyclorama and the Battle of Atlanta." The Indianapolis Star. July 22, 2017. https://www.indystar.com/videos/news/2017/07/22/indianapolis-cyclorama-and-battle-atlanta/103894462/.

"The Minneapolis Cyclorama." Nokohaha. February 4, 2017. Accessed June 17, 2021. https://www.nokohaha.com/2017/02/04/the-minneapolis-cyclorama/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Steven E. Woodworth, Nothing But Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 567–568. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Gary Ecelbarger, The Day Dixie Died: The Battle of Atlanta (New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2010), 213–214. |

| 3. | James M. McPherson, Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief (New York: The Penguin Press, 2014), 205; Brian Holden Reid, The Scourge of War: The Life of William Tecumseh Sherman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 330. |

| 4. | Carole Emberton, Beyond Redemption: Race, Violence, and the American South After the Civil War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 146, 155, 201; Gregory P. Downs, The Second American Revolution: The Civil War-Era Struggle Over Cuba and the Rebirth of the American Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 136; Leon F. Litwack, "Hellhounds," in Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, ed. James Allen (Santa Fe, NM: Twin Palms Publishers, 1999), 8–37. |

| 5. | David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 31–97; Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 73–159. |

| 6. | Chris Brenneman and Sue Boardman, The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beattie, 2015), 14; Ralph Hyde, Panoramania! (London: Trefoil Publications, 1988), 172. |

| 7. | Stephan Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 343; Angela Miller, "The Panorama, the Cinema, and the Emergence of the Spectacular," Wide Angle 18, no. 2 (1996): 35–69. |

| 8. | Miller, "Panorama," 55. |

| 9. | Alison Griffiths, "'Shivers Down Your Spine': Panoramas and the Origins of Cinematic Reenactment," Screen 44, no. 1 (2003): 1–37. |

| 10. | Antje Petty, "German Artists—American Cyclorama: A Nineteenth-Century Case of Transnational Cultural Transfer" (presentation, German Studies Association 34th Annual Conference, Oakland, CA, October 7–10, 2010, Oakland, CA), https://mki.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1100/2014/10/Petty_GSA-2010_Panorama.pdf. |

| 11. | Susan Tenneriello, Spectacle Culture and American Identity: 1815–1940 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 2–14. |

| 12. | Evelyn J. Fruitema and Paul A. Zoetmulder, eds. The Panorama Phenomenon: Mesdag Panorama 1881–1981 (The Hague, Netherlands: Foundation for the Preservation of the Centenarian Panorama, 1981), 18. |

| 13. | Louise Spence and Vinicius Navarro, Crafting Truth: Documentary Form and Meaning (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 11. |

| 14. | William A. Dobak, Freedom By the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867 (Washington, DC: US Army Center of Military History, United States Army, 2011), 501; Thavolia Glymph, The Women's Fight: The Civil War's Battles for Home, Freedom, and Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 10; Judith A. Giesberg, Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women's Politics in Transition (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000), 4. |

| 15. | Stephanie McCurry, Women's War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil War (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019), 204. |

| 16. | William A. Blair, "Reconciliation as a Political Strategy: The United States After Its Civil War," in Reconciliation After Civil Wars: Global Perspectives, ed. Paul Quigley and James Hawdon (New York: Routledge, 2019), 217–231. |

| 17. | Robert Lang, ed. The Birth of a Nation: D. W. Griffith Director (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 134. |

| 18. | Leon F. Litwack, "The Birth of a Nation," in Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies, ed. Ted Mico, John Miller-Monson, and David Rubel (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995), 136–141. |

| 19. | Robert Burgoyne, The Hollywood Historical Film (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 26. |

| 20. | Michael Rogin, "'The Sword Became a Flashing Vision': D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation," Representations 9 (Winter 1985): 150–195. |

| 21. | Milton MacKaye, "The Birth of a Nation," Scribner's Magazine 102, no. 5 (1937): 40–46; James Chandler, "The Historical Novel Goes to Hollywood: Scott, Griffith, and Epic Film Today," in The Romantics and Us: Essays on Literature and Culture, ed. Gene W. Ruoff (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 237–273. |

| 22. | John Belton, American Cinema/American Culture (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 15; Bruce Chadwick, The Reel Civil War: Mythmaking in American Film (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 97. |

| 23. | Ruth Elizabeth Burks, "Gone With the Wind: Black and White in Technicolor," Quarterly Review of Film and Video 21, no. 1 (2004): 53–73; Jenny Barrett, Shooting the Civil War: Cinema, History and American National Identity (London: I.B. Tauris, 2009), 35; Ellen C. Scott, Cinema Civil Rights: Regulation, Repression, and Race in the Classical Hollywood Era (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 157–160. |

| 24. | Davarian L. Baldwin, "'I Will Build a Black Empire': The Birth of the Nation and the Specter of the New Negro," Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 14, no. 4 (2015): 599–603. |

| 25. | Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation: A History of the "Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time" (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 129–170; Cara Caddoo, "The Birth of a Nation's Long Century," in The Birth of a Nation: The Cinematic Past in the Present, ed. Michael T. Martin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 33–45. |

| 26. | Mark E. Benbow, "Birth of a Quotation: Woodrow Wilson and 'Like Writing History With Lightning,'" Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 9, no. 4 (2010): 509–533. |

| 27. | Michael T. Martin, "Revisiting (As It Were) the 'Negro Problem' in The Birth of the Nation," in The Birth of a Nation: The Cinematic Past in the Present, ed. Michael T. Martin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 33–45. |

| 28. | Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Revised Edition (London: Verso, 2006), 201. |

| 29. | Anderson, Imagined Communities, 6–7. |

| 30. | Nicola Cooper and Martin J. Hurcombe, "The Figure of the Soldier," Journal of War and Culture Studies 2, no. 2 (2009): 103–104. |

| 31. | Wilbur Zelinsky, Nation Into State: The Shifting Symbolic Foundations of American Nationalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 155. |