Overview

Series editor Mary E. Frederickson introduces the public health series "Public Health in the US and Global South."

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy. Selected from a competitive group of submissions, these pieces offer new perspectives on the multiple meanings of health, space, and the public in the US and Global South.

Introduction

Global patterns of development over the past two decades have meant that many of the health risks that affected the US South in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries plague the Global South in the twenty-first. Yellow fever, malaria, hookworm, pellagra, and industrial accidents shape life in the developing world. In Atlanta, known as the "public health capital of the world," recent headlines compared the city's HIV "epidemic" to that of African countries. "Downtown Atlanta is as bad as Zimbabwe or Harare or Durban," says Dr. Carlos del Rio, co-director of Emory University's Center for AIDS Research, underscoring the blurred spatial boundaries where inadequate or no access to healthcare perpetuate an ongoing public health crisis.1See "Emory and Atlanta: The Global Health Capital of the World, http://www.emory.edu/home/university/global-health.html; Dave Huddleston, "Atlanta's HIV 'epidemic' compared to third world African countries," WSB-TV, May 6, 2016, http://www.wsbtv.com/news/2-investigates/atlantas-hiv-epidemic-compared-to-third-world-african-countries/263337845.

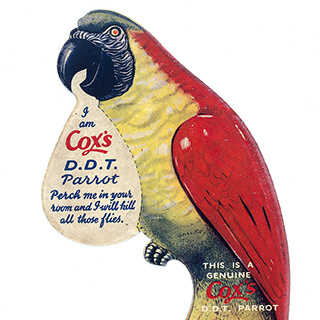

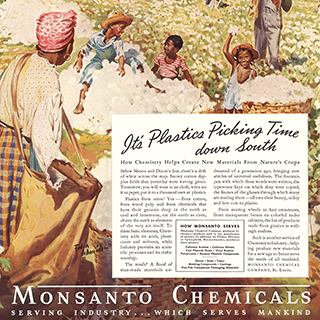

This Southern Spaces series examines public health in rural and industrializing places around the world, reporting on topics that include the history of yellow fever, the environmental effects of DDT, hookworm, and environmental activism. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy.

Public health scholarship builds on the work of scholars in environmental history, medical humanities, and ethics to analyze the cultural and economic factors in health policy and medical care. This history reveals heroes and villains, courageous activists, recalcitrant bureaucrats, and corporate profiteers. Health care workers run the gamut from eugenicists to environmentalists, from misogynists and racists to strong proponents of social justice who understand health care as a fundamental human right. Across generations, the major social determinants of public health remain—class, race, gender, and geography—while the particulars have shifted dramatically. Outrages over food safety and the false claims of patent medicines became public causes in the early twentieth century. Successful campaigns of immunization eradicated infectious diseases such as smallpox, tuberculosis, measles, and mumps. More recently, the work of public health includes: chronic diseases of the heart, lungs, and kidneys; diabetes, tobacco and alcohol use; air and water quality; nutrition and obesity; gun violence; prescription drug misuse; teen pregnancy; and motor vehicle injury and death.

Climate change generates public health threats that include natural disasters and the creation of warm, virus-nurturing environments that promote chikungunya, dengue fever, ebola, and zika—diseases that call to mind the yellow fever, cholera, and malaria that plagued southern geographies in earlier centuries.

The US South's reputation for poor health seems tied to national discourses of underdevelopment and backwardness. Yellow fever, "the scourge of the South," panicked urban populations, discouraged immigration, and disrupted commerce. The yellow fever epidemic of 1878–1879 that swept across the Gulf States and up the Mississippi claimed 16,000 lives. Malaria, with its enervating effects, played a role in shaping the popular image of the "lazy southerner." Tuberculosis plagued the South more than any other section of the United States and hit African Americans especially hard. Widespread poverty for generations following Reconstruction exposed hundreds of thousands of poor, rural southerners to hookworm infection and pellagra. By the end of the nineteenth century a few southern states had established boards of health. By 1913, every southern state had established a state health agency, identified the insect carriers of malaria and yellow fever, and taken up hookworm and pellagra as challenges. Funding for health reform began to increase after World War I. New Deal spending doubled the number of county health departments, from 396 in 1935 to 747 in 1941. Nonetheless, the South continued to lead the nation in the number of stillbirths and maternity and infant death rates, as well as in the incidence of tuberculosis, venereal disease, malaria, hookworm, hypertension, and heart disease. Racial segregation commanded a costly dual system of health care that resulted in devastating disparities in health care for southern African Americans, including inadequate facilities, too few physicians, dramatically higher rates of disease, and a significantly lower life expectancy. Only during and after World War II did the South experience an unprecedented improvement in public health.

During the twentieth century, an enormous health infrastructure emerged, from the glittering buildings of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, to the sprawling campus of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. The architecture of healthcare attests to the long-term intransigence of public health concerns, as well as to the thriving for-profit health business. The brick and stone tuberculosis hospitals that dominated the southern healthcare landscape in the early twentieth century gave way to structures of glass and steel containing hundreds of hospital beds, huge clinics, and multi-million dollar state-of-the-art equipment.

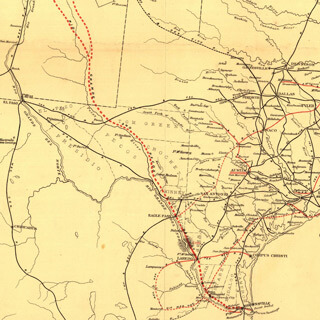

The authors contributing to this Southern Spaces series offer broad perspectives on the multiple meanings of public health. Their research takes us into hospitals and medical facilities, and then out beyond those walls into local geographies. They analyze the cultural and economic consequences of health reform, as well as the social and psychological costs incurred when safeguards fail to protect the health and well-being of the public. The series's first article by Elena Conis, "DDT Disbelievers: Health and the New Economic Poisons in Georgia After WWII," reveals the postwar tensions between global health needs and local health concerns in the southern United States. Second in the series is "The Pursuit of Health: Colonialism and Hookworm Eradication in Puerto Rico" by José Amador, excerpted from his award-winning book, Medicine and Nation Building in the Americas, 1890–1940, which shifts attention from the US South to an area of US imperial expansion after 1898. Amador examines the campaign to control hookworm in Puerto Rico funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, arguing that the spread of US public health campaigns across national borders promoted state modernization in the Caribbean and fostered new international networks of scientific exchange. The third installment in the series by Paul Michael Warden, "Ungesund: Yellow Fever, the Antebellum Gulf South, and German Immigration," addresses the collective medical geography of the Gulf South as revealed through nineteenth-century travel and settlement writing. Warden finds a strong correlation between the discourse of medical geography and German settlement patterns and raises questions about longstanding assumptions regarding the presence of slavery as the determining factor in German settlement.

Selected from a large number of submissions, these essays and other forthcoming publications in the Southern Spaces Public Health Series expand our understanding of the historical and contemporary relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Southern Spaces editorial staff, Eric Solomon and Stephanie Bryan, for their excellent work on the visual media that supplements this introduction.

About the Author

Mary E. Frederickson is a visiting professor in the Department of Behavior Sciences and Health Education at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University. She is also Emeritus Professor of History at Miami University, her academic home for twenty-five years. She serves as the guest editor for the Southern Spaces series, “Public Health in the US and Global South."

Cover Image Attribution:

The Geographical Distribution of Health and Disease, in connection chiefly with natural phenomena. Map by Alexander Keith Johnston, 1856. Courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.Recommended Resources

Text

Amador, José. Medicine and Nation Building in the Americas, 1890–1940. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2015.

Humphreys, Margaret. Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Link, William A. The Paradox of Southern Progressivism: 1880–1930. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Reubi, David, Clare Herrick, and Tim Brown. "The Politics of Non-Communicable Diseases in the Global South." Health and Place 39 (2016): 179–187.

Savitt, Todd L. and James Harvey Young, eds. Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Web

United Health Foundation: America's Health Rankings. "2015 Annual Report." http://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/2015-annual-report.

Arnold, Carrie. "Is America Ready for a New Wave of Tropical Diseases?" CNN. August 13, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/08/13/health/america-tropical-disease/.

"Global Health." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 12, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/index.html.

Office of Minority Health & Health Equity (OMHHE). "CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report (CHDIR)." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/chdireport.html.

Rural Health Information Hub. "Rural Health Disparities Publications." https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-disparities/publications.

Tweedy, Damon. "Being Black can be Bad for your Health: Race, Medicine and the Cruelest Unfairness of All." Salon. October 11, 2015. http://www.salon.com/2015/10/11/being_black_can_be_bad_for_your_health_race_medicine_and_the_cruelest_unfairness_of_all/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | See "Emory and Atlanta: The Global Health Capital of the World, http://www.emory.edu/home/university/global-health.html; Dave Huddleston, "Atlanta's HIV 'epidemic' compared to third world African countries," WSB-TV, May 6, 2016, http://www.wsbtv.com/news/2-investigates/atlantas-hiv-epidemic-compared-to-third-world-african-countries/263337845. |

|---|