Overview

Completed from 1816 to 1817, the Guia de Caminhantes (“Guide for Walkers”) held at the National Library of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro, is one of the few extant cartographic projects completed by a Black artist in the early nineteenth century. Professor Rarey considers this rare atlas and what is known about Anastásio de Sant’Anna, its creator. The Guia demonstrates how one Black cartographer crafted an intermingled perspective of Black, Indigenous, and colonial histories and epistemologies to forge a novel vision of Brazilian national identity on the eve of its independence.

This presentation is an edited version of Professor Rarey’s lecture at Emory University on January 30, 2025. The full video is available by clicking here.

“On Maps, Race, and Diasporic Self-Fashioning in Early Nineteenth-Century Brazil” is part of the Southern Spaces series Map It: Little Dots, Big Ideas organized by Professor Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi of Emory University’s Department of Art History.

What happens when we put Black Studies in conversation with the history of cartography? Katherine McKittrick, one of the key thinkers in Black Geographies, answers this question in a foundational essay when she writes that “Transatlantic slavery…was predicated on various practices of spatialized violence that targeted Black bodies and profited from erasing a Black sense of place.” As a result, she notes, “Black diasporic histories are difficult to track and cartographically map.”1Katherine McKittrick, "On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place," Social & Cultural Geography, 2011, 12: 948.Black Geographies as a subfield emerged in the 2000s to reckon with McKittrick’s argument, mainly, the ways histories of Blackness axiomatically raise questions of free and restricted movement; territorial boundedness and segregation; and fugitivity from the earliest plantations to the present-day prison-industrial complex. For McKittrick, the structural histories of racial disenfranchisement, plantation slavery, and the “relational violences of modernity” collectively necessitate that we consider the diversity of what she calls “alternative mapping practices.” By this she means attending to the spatial organization of maroon communities; hidden escape routes used by those fleeing slavery, as well as the frequent disguising of these escape routes in music and song; and family and genealogical maps maintained by those who had no legal or citizenship status. In this sense, Black Geographies fundamentally asks what may count as a “real” map and, more importantly, what forms of power and privilege the designation of “map” bestows on the objects it labels. Pushing this point, cartography historian Matthew Edney goes so far as to argue that “there is no such thing as cartography.”2Matthew H. Edney, 2019. Cartography: The Ideal and its History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 1.Edney instead frames “cartography” as an exercise in aestheticizing and naturalizing relations of power; an idealized performance of racialized and colonial hierarchy enacted through its material output, the “map”. Edney’s observation carries special resonance for histories of Black cartography, where scholars have often framed the historic relationship between material cartographic objects and Blackness as an almost axiomatic opposition. And with perhaps good reason: looking at the cartographic archive of the slavery-era Americas, one quickly sees Blackness rendered either as an aestheticized form of subservience to whiteness, or as an irritating anti-colonial node to be eliminated.

As an example of how this tension plays out, we can look to this work from 1773, The Layout of the Conquered Maroon Village Called Boekoe, by Dutch cartographer Juriaan François de Friderici. It depicts the layout of Fort Boekoe, a fortified maroon settlement in what is today Suriname, in northern South America, that was razed by a Dutch militia in September of 1772. The map’s title and aerial-view perspective make it clear that the maroon village itself served as impetus for the map’s creation, yet only as a form of violent erasure: a dialectic that underscores why maroon communities have been such critical points of theorizing for Black Geographies. Yet, also consider the tension Friderici produces in the map’s elaborate title cartouche, held up by a Black figure whose scantily-clad form implicitly references his enslaved status. The figure enacts a colonial fantasy of converting marronage to subservient labor, and here evokes his own subjugation through the map’s material production. Yet, the figure’s equally dominating presence and confident pose also suggest the persistence of maroon life and resistance, even after Fort Boekoe’s seeming destruction.

Black cartographers have long responded to this dialectic of spectacular presence and invisible subjugation that runs through cartographic renderings of Black spaces and places. As one brief case study, in the 1940s, Louise E. Jefferson – a noted African American illustrator and designer – produced a series of works meant to interrogate presumptions of whiteness and the fixity of identity which served as preconditions for depicting the United States as a nation. In her 1945 Uprooted People of the U.S.A., Jefferson depicts abandoned villages, overcrowded transit centers, and internal refugee camps which all emerged because of the dramatic economic and social shifts wrought by the country’s World War II efforts: a depiction of the United States as a country defined by massive internal displacement and populated by what she terms “victims of war.” Her Americans of Negro Lineage, produced the following year, weaves stories and illustrations of Black doctors, musicians, laborers, and politicians together with statistics on Black populations, internal migrations, and the history of slavery.

By recasting the standard political framing of the forty-eight states as an image and icon of the country, Jefferson’s two maps themselves seek new forms of belonging in a nation defined by racial disenfranchisement; and to reckon with how a static map elides the constant histories of migration and identity-making that underly it. In this way, Jefferson’s work responds, perhaps, to one model of Black Geographies that suggests that the visibility of Black histories depends on framing Blackness as “uprooted,” and perhaps in axiomatic opposition to the modern Western nation-state and the material maps which instantiate it. Jefferson’s works provide the impetus to look backward, to ask how Black artists have thought about the history of mapmaking and its relationship to racial formation and especially to racial fixity. Stated bluntly, what demands does Blackness’ inextricability from histories of forced displacement and archival erasure place on those that wish to engage with material maps, a medium that might privilege histories of fixity and boundedness?

I ask this question by looking to the Guia de Caminhantes. Completed from 1816 to 1817, the Guia de Caminhantes (“Guide for Walkers”; hereafter referred to as the Guia), held at the National Library of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro, is one of the few extant cartographic projects completed by a Black artist in the early nineteenth century.

In the Guia’s introductory text, which you see here on the top half of the cover page, its artist, Anastásio de Sant’Anna, identifies himself as an “old” painter of mixed race, and a resident of the city Salvador (also known as Bahia), a major port city in northeastern Brazil where he had long lived and where he completed the work.

The Guia has attracted scarce attention in Portuguese-language scholarship and has never been discussed in English prior to this talk. Yet, it is a rare example of a manuscript map of Brazilian territory produced outside of the context of a military or surveying expedition in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Far exceeding its somewhat timid title, the Guia is more properly thought of as an atlas, and indeed, potentially the first one ever produced in Brazil: an unbound grouping of thirteen hand-drawn, hand-colored, aerial-view maps depicting, as the work’s cover page outlines, “Kingdoms and Provinces of America, especially of Brazil.” While it opens, as we will see, with a large hemispheric map of the Americas and a map of Brazil, the rest of the Guia consists of eleven aerial-view maps of Brazil’s captaincies (the name for Portuguese colonial Brazil’s political divisions), which collectively detail their rivers, mountain ranges, beaches, settlements, churches, sugar mills, Indigenous settlements, and roads: all landmarks that would be important to any early nineteenth-century “walker” referenced in the Guia’s title.

The Guia evinces the artist’s intimate knowledge of two centuries of the history of cartography and landscape painting, and these references potently intersect with the social politics around the artist’s racial identity. In turn, as we will see, these maps reproduce and subtly shift conventions of Portuguese military cartography, while also traversing the boundaries between military precision and painterly imagination. Sant’Anna produced, re-framed, and challenged the intersections of empire and racialization in a political and social context in which race strongly stratified—but did not neatly latch onto—the hierarchies of colonial society. In turn, the Guia foregrounds the antiquity and contemporary persistence of Black and Indigenous histories in Brazil and the wider Americas. As if responding to Jefferson’s Uprooted People of the USA more than a century before she produced it, the Guia frames Blackness not as diasporic, but rather as Indigenous to the Americas and in turn constitutive of the modern nation-state. In this way, the Guia starkly contrasts with the maps discussed previously by productively interrogating the opposition of violent colonial cartographies and Black alternative mapping practices. In so doing, it demonstrates how one Black cartographer crafted an intermingled vision of Black, Indigenous, and colonial histories and epistemologies to forge a novel vision of Brazilian national identity on the eve of its independence.

In the Guia’s second map, “Of All Brazil,” Sant’Anna renders latitude with “the city of Bahia” at zero (I’ve indicated Salvador’s location here with a large red dot). The gesture may speak to Sant’Anna’s pride in his home city, but it also testifies to Salvador’s critical political position as Sant’Anna completed the Guia in 1817. Though Salvador had served as the capital of Portuguese colonial Brazil since the mid-sixteenth century, the city had been relegated to secondary status after the capital’s 1763 transfer to Rio de Janeiro, hundreds of miles to the south. Salvador again toyed with primacy in the early nineteenth century as the Portuguese royal court fled the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and temporarily relocated to Brazil, making Brazil the first country in the Americas to house the government seat of a European empire. In 1808, King João VI and his family spent one month in Salvador before moving on to Rio de Janeiro; Rio would remain the Portuguese empire’s temporary capital until the Empire of Brazil’s independence from Portugal in 1822.

The Portuguese Crown’s relocation to Brazil encouraged the colonial settlement of the Brazilian interior, which prior to this period had been predominantly populated by Indigenous peoples who had been displaced by colonial activity on the coast. This means Sant’Anna completed the Guia during a surge of interest in mapping the country’s interior as a proxy for territorial conquest and implicit civilizing. Sant’Anna’s Guia also seems to preface the Brazilian Empire’s 1824 Constitution, which extended citizenship to anyone born in Brazil, regardless of racial background (though this excluded the millions of people of African descent then enslaved in Brazil). Even then, as Sant’Anna completed the Guia, Brazil’s “Atlantic frontier became a theater of staggering anti-Indigenous violence and the entrenchment of African-based slavery” as a byproduct of increased settlement.

Living in Salvador in the early nineteenth century Sant’Anna would have experienced the political implications of such inequities firsthand. He was part a large, vibrant, diverse Black population in a city that for two centuries had been a major disembarkation point for enslaved Africans in Brazil (and Brazil itself received around forty percent of all enslaved Africans who arrived in the Americas between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries). In Sant’Anna’s time, two thirds of Salvador’s population was of African descent, enslaved and free, while shipping routes—established around the turn of the eighteenth century—directly linked Bahia with West African ports. Anyone walking around Salvador could see evidence of the city’s African character everywhere: African-born merchants dominated the city’s street economy by selling food and African-made textiles, while African languages were as commonly spoken as Portuguese. Bahia’s African populace also shaped its politics: a series of African-led revolts and conspiracies in early nineteenth-century Bahia shook the foundations of the city’s slavery system and its racial order.

Yet outside of the political and social context in which Sant’Anna worked, we have very little other information about him. Portugal’s National Archive contains the earliest known mention of the artist, albeit when Sant’Anna was likely middle-aged: a 1796 judicial proceeding which named Sant’Anna as defendant. The document describes Sant’Anna as a free married man of mixed race who painted maps and created perpetual lunar calendars. Over two decades before producing the Guia, Sant’Anna was already well known for his artistic and cartographic creations. The document describes him as an “official painter”, a designation suggesting that Sant’Anna was a respected professional and, by implication, an active participant in one of Salvador’s many mixed-race, Catholic brotherhoods. These religious mutual aid organizations that were a staple of Brazilian social life, many of which supported free professional artisans and craftspeople. Specifically Black Catholic brotherhoods had long served as incubators of Black agency in Brazil by purchasing freedom for the enslaved, providing social and economic aid to members, and creating pathways for social mobility and collective solidarity. Sant’Anna’s likely membership in one of these brotherhoods, though, does little to help us understand his political orientations: while directly connected to the rise of Black political consciousness through the nineteenth century, brotherhoods were diverse in their priorities and social orientations.

Attesting to the artist’s commitment to cartography, Caio Figueiredo Fernandes Adan and Iris Kantor have identified a series of unsigned early nineteenth-century manuscript maps of Brazil, which they attribute to Sant’Anna on stylistic grounds.3Caio Figueiredo Fernande Adan and Iris Kantor, A cartografia de um oficial pintor de mapas liberto: Estudo de atribuição de autoria (Bahia-Brasil, século XIX). In 8a SIAHC Siímposio Ibero americano de História de Cartografía/O mapa como elemento de ligação cultural entre a América e a Europa. Edited by Carme Montaner and Carla Lois. Barcelona: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya, 2012) 120–33. Distributed at archives in Rio de Janeiro, some of these maps appear to be early studies for those found in the Guia, suggesting that the Guia was the culmination of years of study and analysis by the artist; in short, his magnum opus. Yet Sant’Anna’s decades of work in cartography prior to the Guia is striking given that he does not appear to have even been employed by the military or studied military cartography in an official capacity.

I say this because, between the mid-1700s and Brazilian independence in 1822, almost all known manuscript maps of Brazilian territories were produced in the context of military surveying expeditions. Even stranger, the Guia’s maps reproduce some of the major conventions of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Portuguese military cartography: an emphasis on aerial perspective; defined captaincy borders; fastidious naming of rivers and towns; standardized representations of topographic features; and exacting scales for measuring distance. We can see at the bottom left of this map Sant’Anna precise scale for measuring distance; and if we return to the cover page of the Guia, at bottom right, we see his detailed guide for interpreting the symbols and designs on his maps.

These conventions originally emerged from eighteenth-century Portuguese military training reforms that prioritized cartographic training alongside scientific precision and technical uniformity. These military and cartographic reforms went together with desires in Lisbon to increase control over what it viewed as colonial hinterlands. Imperial reforms instituted in the second half of the eighteenth century utilized military cartography as a tool of colonial authority, conducting surveys to identify and suppress rebellious Indigenous and maroon communities while also assimilating inland territories and Indigenous peoples into direct Portuguese territorial control.

Given his lack of military background, Sant’Anna’s work in cartography prompts two questions. One is factual: how did Sant’Anna access the knowledge and military maps necessary to produce the Guia? Other scholars have productively suggested that the Bahia Public Library in Salvador may have provided Sant’Anna access to a range of manuscripts and printed maps on which to base his designs, especially since the library received a large donation of maps in 1812. Sant’Anna also would have had access to the Bahia Military Academy, where interested laymen like him could attend classes on military cartography.

But my hopefully informed speculation on the question of Sant’Anna’s access to military cartography does not answer the second question: why was he interested in mapmaking at all? One clue comes from the Guia’s long opening text, where Sant’Anna describes the Guia as a correction for the “many errors that are found in some imprecise Maps of the interior” of Brazil, by which he means military manuscript maps. Sant’Anna claims the Guia corrects the names of rivers; presents the proper names for towns and settlements; and establishes formerly erroneous latitudinal and longitudinal lines.

However, naming practices are never neutral. Sant’Anna’s Guia throughout makes “a point of giving Indigenous names to places, rivers and cities.” Sant’Anna’s reliance on Indigenous place names does not necessarily signal his investment in a kind of contemporary anti-colonial politics. Rather, I forward that it may reflect the complex and shifting implications of the ongoing Indigenous presence in Brazilian history, one which could be antagonistic to or supportive of colonial projects.

Sant’Anna’s effort to correct the “errors” of contemporary cartography begins not with maps, but with an unprecedented watercolor painting on the bottom left of the Guia’s title page.

The image depicts an encounter at “Jiquitaia”, described by Sant’Anna as a beach in Salvador formerly known as a thriving commerce center for the area’s Tupi population, the primary Indigenous group of Brazil’s Atlantic coast. Though, in 1817, Jiquitaia was home to a newly-constructed Portuguese military fort —one that still utilized the beach’s Tupi name and so shows the Portuguese imperial appropriation of Indigenous landscapes—Sant’Anna envisions Jiquitaia as a place of ethnic egalitarianism and relative peace. Sant’Anna’s painting presents a group of white European men—identified by their skin tone and their dress—trading weapons, alcohol, and other objects on the beach. Tupi persons, depicted by Sant’Anna with feathered headdresses and skirts, interact on equal footing, as do persons of African descent. The two Black women he depicts appear to be in relationships with Indigenous men; one at left holds their child. In the foreground, a man with skin tone matching the white Europeans emerges with an Indigenous woman from behind a banana tree. His red cap and feathered skirt suggest he has long lived in the area’s Tupi communities.

As the figures on the beach point to trade goods with looks of curiosity and contemplation, and as they wear clothing contemporary to the sixteenth century, the watercolor evokes a sense of initial encounter, as if the Europeans are arriving at Jiquitaia for the first time. Sant’Anna’s title for the painting furthers this reading. “Kirimurê: Ancient Gentilic name of Bahia, and place where the City of Salvador was founded”, references the beginnings of Bahian history while also emphasizing the area’s Tupi name. However, further details complicate this initial timeline. Most obvious is the figure at bottom left, wearing a large feathered headdress, which has been identified as Catarina Paraguaçu, a sixteenth-century “Tupi indigenous woman from Bahia, who was offered by her father, the chief Taparica, to the Portuguese castaway Diogo Álvares, known as Caramuru”, an identification supported by the white figure accompanying her. In turn, Sant’Anna presents Black residents in Kirimurê and shows them as full members of Tupi worlds, even though no enslaved Africans arrived in Brazil prior to the mid-sixteenth century, after the “founding” of Salvador the title references. By including persons of African descent and Indigenous names in the scene at Jiquitaia, Sant’Anna does more than forward a vision of Brazil’s multiethnic history that would soon be enshrined in the 1824 Constitution. He also argues that Bahia’s “founding” is, perhaps, inextricable from the ways Black, European, and Indigenous worlds commingled and co-evolved in Brazil, independent of the histories of exploitative labor and land dispossession that characterized the late colonial and postcolonial imperial periods.

From a contemporary vantage point, this scene of egalitarian encounter appears like an apology or erasure of colonization’s violence. However, looking to the possible inspirations for Sant’Anna’s painting, critical distinctions emerge that show the force of his vision. The painting’s wide-angle landscape view, receding into a bay and framed with Brazilian flora, suggests Sant’Anna’s familiarity with longer histories of Dutch painting used to naturalize and aestheticize Brazilian landscapes and histories of forced labor.

A 1649 painting by the Dutch artist Frans Post testifies to the role of Dutch landscape painting in aestheticizing enslaved labor in colonial Brazil. A wide view looks back to rolling hills punctuated with lakes and rivers. Industrialized sugar mills sit atop the hills at right, while enslaved people work a bit of cleared land at center. Post renders the centrality of industrialized slavery to Dutch Brazil as a natural, aesthetic inheritance of the Brazilian landscape. A small anteater traipses in the foreground, just in front of a prominent pineapple, while a tall palm tree at right – displaying ripe palm fruits dangling from the top—frames the image.

Sant’Anna’s artistic choices (see “Kirimurê” watercolor) suggest a throughline between colonially cultivated visions of tropical, edenic labor and Sant’Anna’s own painting. The foreground pineapple appears once again, as does the framing palm tree, alongside further floral additions like cashew fruits and a banana tree. However, unlike Post, Sant’Anna puts human action squarely in the foreground and emphasizes barter and economic exchange over attempts to aestheticize forced labor. Sant’Anna’s quite literal foregrounding of the word “Jiquitaia” may reinforce the point: the beach’s name is the Tupi word for the powdered form of a chili pepper native to the Americas. Highly desired by the Portuguese who purchased it from Tupi merchants, the chili was soon exported through Portuguese trade routes into Iberia and Africa. By the early seventeenth century, people across the Atlantic world instead called this chili malagueta after an unrelated but equally prized West African spice. Culturally and etymologically, Sant’Anna’s use of “Jiquitaia” harkens less to a pre-contact image of Tupi history than a wide-ranging reference to the co-evolution of Indigenous, African, and European knowledge in and through Atlantic commerce. Fittingly, Sant’Anna does not restrict Black and Indigenous figures to laborers or workers for an invisible white elite—in which the value of their lives would be restricted to their bodily production—nor, in turn, are they portrayed as being in awe of, or saved by, white settlers in the common trope of European saviorism that would run through Brazilian history paintings later in the nineteenth century. Instead, the beach scene places economic and cultural agency in the bodies and minds of Afro-Indigenous histories, while also disentangling sartorial practice and cultural identity from skin tone.

In this way, I read “Kirimurê” as Sant’Anna’s early effort to work through what the Black and Native Studies theorist Sandra Harvey outlines as a key problem in later twentieth- and twenty-first-century Black intellectual history and politics: how articulations of Black identities are often framed around what she frames as “an existential pull … that renders Black existence, especially but not solely outside of Africa, permanently and always already ‘unrooted’”. The counterpoint to that sense of displacement, Harvey notes, is often “the Western nation-state”.4Sandra Harvey, "Unsettling Diasporas: Blackness and the Spectre of Indigeneity," Postmodern Culture, 31: 1, 2 (2020, 2021).) Faced with a tension between Blackness’ uprooting and the patriotic cartography of Brazilian nationhood, Sant’Anna created a painting that refused to place Blackness in opposition to Indigeneity, a point underscored by the inclusion of the Afro-Indigenous child in the scene at Jiquitaia. As I detail below, he constructs a vision of Bahia’s founding that roots Blackness and even African botanicals as Indigenous. And through the presentation of Caramuru, the castaway, he refuses to let whiteness claim the political project of the nation-state, instead showing it as an equal inheritor of diaspora, Indigenization, and forced acculturation.

This vision of the co-constituted Indigeneity of Tupi and Black worlds Sant’Anna presents as constitutive of Brazil may be reinforced in the botanicals he depicts. Cashew fruits, at left (see “Kirimurê” watercolor painting), are native to Brazil, but bananas and pineapples—two fruits that Sant’Anna positions as native in this retelling of Bahia’s founding—were transported to Brazil from West Africa in the sixteenth century. While Frans Post’s mid-seventeenth-century painting participates in a longer colonial strategy of cultivating visions of botanical hybridity to aestheticize and naturalize the violence of settler colonialism, Sant’Anna reframes foreign transplants—which include human beings and cultivated plants—as altogether native to Bahia. This is what separates Frans Post from Sant’Anna: the latter asserts the antiquity of Indigenous and African shared knowledges and harkens to a diverse, vibrant world that includes them both, independent of histories of European domination. However, complicating this reading is another background detail showing how Sant’Anna continues to play with timelines: a battle scene likely referring to the 1625 joint Spanish–Portuguese reconquest of Salvador following its Dutch occupation. Perhaps Sant’Anna is collapsing the major events of Bahia’s history here, but it also speaks to the proto-nationalist tone of his Guia by re-envisioning the moment when Bahia was brought back under Portuguese imperial sovereignty, a point that may have carried strong weight as Brazil served as temporary home to the Portuguese Crown.

Why might Sant’Anna be asserting this vision of Afro-Indigenous antiquity and Brazilian national and imperial pride all at once? What motivated his project to imagine the political contours of Blackness outside of a diasporic framing?

Sant’Anna’s self-description on the cover page as a “painter” as well as an “old pardo” may reveal much about his intent. Pardo, a Portuguese word which has no translation into English, is the general term still preferred by multiracial Brazilians to describe themselves. In the early nineteenth century, pardo indicated a person’s African—and potentially also Indigenous—ancestry, but also more generally referred to someone who was neither white (branco) nor Black (preto), with the latter term typically suggesting enslaved status. As was true throughout colonial-era and early imperial Brazil, vocabularies and self-definitions of color were often “more to indicate social positions than referring specifically to an individual’s nature.” In this sense, pardo was often equivalent to mulato—another term referring to multiracial ancestry—but mulato carried stronger pejorative connotations. Sant’Anna’s upbringing in the second half of the eighteenth century took place around what the historian Miguel A. Valerio outlines as a “popular notion that mixed-race Afro-Brazilians constituted colonial Brazil’s most deviant and unruly socioracial group.” In this context, Valerio elaborates, those who could often expressed a “preference for the term pardo instead of the sullied one of mulato, [which was] popularly associated with licentiousness and ungovernability.”5Miguel A. Valerio, "The pardos’ triumph: The use of festival material culture for socioracial promotion in eighteenth-century Pernambuco," Journal of Festive Studies 3:49, 2021.

Sant’Anna’s self-definition may be related to his artistic prowess. Pardo artists in late colonial Brazil had greater access to artistic work and exploration and so could pursue opportunities unavailable to darker-skinned Brazilians in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. However, Sant’Anna may also have been invested in showing the role of pardos in the formation and participation of a nascent Brazilian national identity, as well as negotiating their political position in the midst of the movement of the Portuguese court and the African rebellions at the time he created the Guia. Sant’Anna’s sole reference to racial categories in the Guia is telling in this regard.

The Guia’s fifth map,depicting the captaincy of Mato Grosso in central Brazil, contains an intriguing detail along the bottom edge. Here, Sant’Anna relays the story of Tomás da Natividade, a pardo man, who was made a salaried infantry captain by the governor.

Why would Sant’Anna have gone out of his way to relay this little-known story? Did Sant’Anna delineate Natividade’s race as pardo—same as the artist—as a testament to his social position, either by status or by aspiration, to prove pardos’ participation in the construction and maintenance of the Brazilian state? Did Sant’Anna also testify to the position of pardos in a social context where they routinely faced barriers in compensation for their service in colonial conflicts? Intriguingly, Sant’Anna may have known pardos in Bahia as both artisans like him and militia members: at the time he completed the Guia, 60% of Salvador’s fourth militia regiment, which was reserved for mixed-race Brazilians like Sant’Anna, were employed as artists. Three were painters. But all likely held far less wealth than their white counterparts in the second regiment. While mixed-race Brazilians were common in Portuguese militia ranks, as were Indigenous Brazilians, their racial status posed frequent barriers to earning full salaries and land rights. And finally, might the reference to Natividade here remind the Guia’s readers of the political differences between Africans and Brazilian-born creoles like Sant’Anna, none of whom participated in the Bahia rebellions, and indeed, were likely among the militiamen who suppressed an African-led uprising near Salvador in 1816, just as Sant’Anna began work on the Guia?

Small details like this begin to put the viewer on notice of the multiple, overlapping political interventions in Sant’Anna’s work. This continues in the first manuscript map of the Guia: a planisphere of the Americas.

As art historian Tatiana Reinoza has outlined, the planisphere was deployed as a technology of what she calls the “Western cartographic gaze” and a proxy for territorial conquest and racial hierarchization reproduced on countless travelogues and cartography manuals dedicated to the colonization of the Americas, as we see in this 1703 frontispiece.6Tatiana Reinoza, Reclaiming the Americas: Latinx Art and the Politics of Territory (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2023): 18. Yet here, the map’s cartouche at bottom center—typically the domain of colonialist fantasies about Americas as an unpopulated territory prepared for the wide implantation of European settlements, or the deployment of figures that confine and define Indigenous and Black labor—instead emphasizes Indigenous empires. Sant’Anna’s text notes the “city of Mexico” and the “city of Cusco”, capitals of the Aztec and Inca states, respectively, their first and last rulers, and those rulers’ undoing by the Spanish in 1521 and 1533. Again, Sant’Anna not only highlights the antiquity of Indigenous civilizations here, but even asserts a new theory of the peopling of the Americas: Sant’Anna titles his map as actually identifying the “parts” from which those who populated the Americas came: “if from Asia, as various authors write, see the parts of China, Japan, and Tartary …and those who came from … Europe and Africa”. Sant’Anna collapses the entire history of the Americas’ peopling, putting all histories of forced and voluntary migration on equal footing while, importantly, decentering Europe spatially and discursively.

Sant’Anna’s map of Brazil, second in the Guia, further suggests his inspiration from much earlier works. Most maps of Brazil at this period were oriented with north at the top, while also outlining the Atlantic coastline and fleshing out the country’s interior: moves reflective of a kind of cartographic proto-nationalism that sought to form Brazil into an identifiable territorial boundary prior to independence in 1822. Such maps helped to render the nation as what the historian Sumathi Ramaswamy calls a “geo-body” necessary for would-be citizens to “see” the country politically and, in turn, to socially attach themselves to it.7Sumathi Ramaswamy, 2014. Maps, Mother/Goddesses, and Martyrdom in Modern India. In Empires of Vision: A Reader. Edited by Martin Jay and Sumathi Ramaswamy (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014): 420.This scheme was then reproduced on a global range of engraved and teaching maps after Brazilian independence, such as this example produced in Philadelphia in 1818 (below, left).

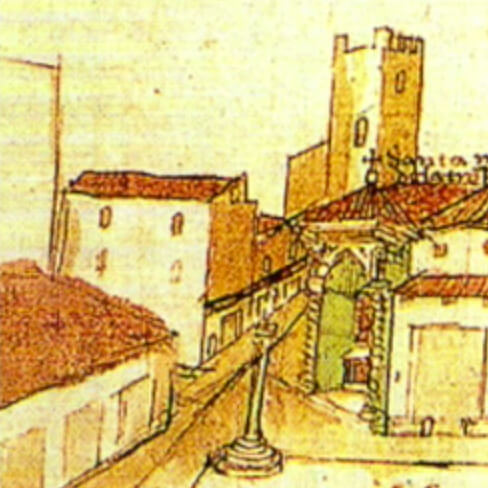

Sant’Anna’s Brazil breaks from this schema, orienting west at the top, a change that neither formed part of Sant’Anna’s corrective efforts nor would have been reproduced in any contemporary work. This style harkens to the sixteenth and seventeenth century, where European—especially Dutch—colonial cartographers commonly oriented Brazil with west at the top, such as in the 1644 example (above, right), which became the basis for nearly a century’s worth of maps in its wake. Also note here that this map contains a prominent inset, at top, depicting the bay of the city of Salvador, and so further speaks to Sant’Anna’s Bahia-centrism.

Sant’Anna’s Brazil also reduces the size of the Atlantic Ocean so that the west African coast peeks through the bottom right. This required shifting of the spatial dynamics from the planisphere the map before, suggesting the move is intentional. This style of showing the tip of Africa with Brazil emerged in the 1500s. Common through the middle of the eighteenth century, this style emphasized Brazil and Africa’s proximity to imply the facility of trafficking humans and goods between them.

In some cases, the link was explicit: the frontispiece to French trader Jean Barbot’s 1688 travelogue concerning his time in West Africa depicts the ocean as a connector between Brazil and West Africa, while two Black figures—aesthetic, celebratory archetypes of the slave trade—flank it. Yet this singular framing of Brazil and West Africa had effectively disappeared by the early nineteenth century. Is Sant’Anna here continuing to extol the slave trade as the backbone of Brazil’s economy—potentially a point that could further distance his racial subjectivity from associations with slave status? Might he also be subtly referencing Brazil’s strong African presence, something further suggested by the oversize importance given to Africa in the planisphere, where the continent almost dominates a map purportedly focused on the Americas? And if so, how does this detail operate in tension with the scene at Jiquitaia, which effectively refuses an image of Blackness tied to Atlantic slavery or diasporic African origins?

Sant’Anna’s eighth map, which depicts northeastern Brazil, may further testify to his work’s historical references and the multilayered histories of diaspora that inform it. Again, shifting typical orientation conventions by depicting northeastern Brazil with south at the top – he loves playing with perspective and directionality – Sant’Anna includes a critical detail: at the bottom of the map, he paints a small black building and labels it “Tapera de Angola; or Palmares.”

Palmares is the common name for a collection of maroon polities that existed in this region during most of the seventeenth century. At its height, Palmares had a population of many thousands, and was politically powerful enough that it conducted major conflicts and signed treaties with the Portuguese and the Dutch. Yet Palmares’ assumed destruction in 1695 means that it was an atypical location to be referenced on a map of the early nineteenth century. Indeed, only one other known map from Brazil’s entire colonial period—a map of this same region commissioned in 1766—names Palmares.

Moreover, the Guia’s pairing of “Tapera de Angola” and “Palmares” is unique in the history of cartography. The name “Tapera de Angola” only appears on one other known map: at the far bottom right of Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu’s oft-reproduced 1662 map of northeastern Brazil, depicting the region’s occupation by the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century. Sant’Anna’s use of this phrasing suggests he used Blaeu’s map specifically as a source of inspiration, nearly a century-and-a-half after its production (and in turn further supports the idea that Sant’Anna is taking broad inspiration from seventeenth-century Dutch Brazilian visual culture).

Naming Palmares in this way may have carried special resonance for Sant’Anna’s evocation of Brazil’s constitutive Afro-Indigeneity. On one level, “Tapera de Angola, or Palmares,” brings into intimate relation phonemes from three languages: “tapera”, an Indigenous Tupi word referring to a ruined or destroyed settlement; “Angola”, the central African polity strongly associated with Palmares, and the region commonly cited as its cultural and philosophical origin point; and “Palmares”, the Portuguese term for palm trees. Sant’Anna uniquely intermingles these sounds on the map, as if linguistically reproducing the kind of multiracial egalitarianism painted on the Guias’s frontispiece. Beyond the multivocality Sant’Anna’s naming provides, we cannot know how Sant’Anna understood the words’ meaning. Did he know, for example, that “tapera” referred to an abandoned settlement? What might this have meant for his evocation of “Angola” and the suggestion that this African polity, or at least its memory, existed or was even at home in Brazil—yet another iteration of the continent’s vibrant proximity to, and co-constitution of, the Brazilian state? If Sant’Anna did understand Palmares as abandoned or destroyed, what might he suggest by re-naming it here and connoting the potential for regeneration and new settlements in the area, maroon and colonial alike, long after Palmares’s destruction? And finally, how might we put this point in conversation with Sant’Anna’s insistence that previous cartographers had made “imprecise” maps of the interior of the state? Why did he make a specific choice to emphasize this historic terminology, and thus bring into sharp relief the coeval histories of Black, Indigenous, and white European diasporas? As elsewhere, Sant’Anna’s work provides few clear answers. Yet, perhaps it is precisely his emphasis on multilayered, multi-referential ambiguity, and the strategic intermingling of colonial, Black, and Indigenous epistemologies that provides the Guia its force.

I want to conclude with the words of geographer Chérie N. Rivers, who writes that “To explain [one’s] origins in relation to a modern political map is to accept a specific construction of space and time that imprisons [oneself] in the geography of global power.”8Chérie N. Rivers, To Be Nsala’s Daughter: Decomposing the Colonial Gaze (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022) 31. For Rivers, the line drawing and mapmaking of longstanding colonial relations presumes a geographic and spatial fixity that attempts to force racial subjectivity into a kind of essentialized boundedness and, in so doing concretize its utility for political and economic exploitation. Anastácio de Sant’Anna worked in the wake of cartographic projects of the colonial Americas which resonate deeply with Rivers’ argument about attempts made to codify and subdue racial identities in the service of proto-nationalist imaginaries, slavery economies, and military conquests. Yet, as “real” maps attempted to instantiate racial hierarchy, practices of Black fugitivity and independence threw them into ontological crisis. As outlined at the beginning of this essay, the work of theorists of Black Geographies show the consistent inadequacy of maps produced in the service of colonial projects, either by intentionally obscuring forms of resistance embedded in the very landscapes they represented, or by failing to incorporate—as a function of their medium—the manifold processes by which those in diaspora exist and move in and remember the world.

In its foregrounding of Black and Indigenous histories and placenames, in its evocations of Africa’s proximity to Brazil, and in its presentations of Blackness’ Indigeneity to Bahia, we might see in Sant’Anna’s Guia an effort to visualize those very forms of place- and space-making obscured by colonial military cartography; to, in other words, re-map and re-animate Black and Indigenous lives beyond the confines of the modern political map. The Guia explores and disentangles the historical timelines, diasporic histories, and racial imaginaries that pushed its maker to occupy a subjective position in the racial strata of the Portuguese Empire and the nascent Brazilian state. In this way, perhaps the Guia functions less as a political statement than as Sant’Anna’s attempt to work through the contours of a racial and political schema that asked him to choose between his mixed-race ancestry and his patriotism, or between his Blackness and his rootedness in and patriotism to Bahia. The Guia interrogates the extent to which cartography may not erase, but rather could foreground, a vision of Black history as part of the state’s geo-body. The Guia may not signify “an outright rejection of the colonial geographic and cartographic project as much as an underscoring of its inadequacy”, which might “distinguish patriotic art’s investment in the map form from the state’s command mapmaking ventures.” Through his genre-bending experimentations across painting and cartography, Sant’Anna attempted to rethink the genealogy of cartography in his homeland, all while asserting his—and other pardos’—sense of belonging and centrality to it.

About the Author

Matthew Francis Rarey is associate professor and chair of the Department of Art History at Oberlin College. He is author of Insignificant Things: Amulets and the Art of Survival in the Early Black Atlantic (Duke University Press, 2023). This Southern Spaces presentation is derived from an essay published by Professor Rarey in Arts in 2024, available here.

Recommended Resources

Chérie N. Rivers. To Be Nsala′s Daughter: Decomposing the Colonial Gaze. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023.

Edney, Matthew H. Cartography: The Ideal and Its History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

McKittrick, Katherine. "On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place." Social & Cultural Geography 12, no. 8 (2011): 947–963, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.624280.

Ramaswamy, Sumathi. "Visualising India’s Geo-body: Globes, Maps, Bodyscapes." Contributions to Indian Sociology 36, no. 1–2 (2002): 151–189, https://doi.org/10.1177/006996670203600106.

Reinoza, Tatiana. Reclaiming the Americas: Latinx Art and the Politics of Territory. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2023.

Web

Cipriano, Ana Paula, Sílvia Lomba. "Reclaiming the Caramuru Catarina Paraguaçu Indigenous Territory," Meli Bees Network gUG, November 14, 2023. https://www.meli-bees.org/reclaiming-the-caramuru-catarina-paraguacu-indigenous-territory/.

Dutch Culture. "Rediscovering Fort Boekoe: A VR Journey into Suriname’s Maroon Resistance," https://dutchculture.nl/en/news/rediscovering-fort-boekoe-vr-journey-surinames-maroon-resistance.

Harvey, Sandra. "Unsettling Diasporas: Blackness and the Spectre of Indigeneity," Postmodern Culture 31: 1, 2 (2020, 2021). https://www.pomoculture.org/2021/09/16/unsettling-diasporas-blackness-and-the-specter-of-indigeneity/.

Widener, Henry Granville. "Brazilian Independence: a Bicentennial Commemoration from Afar, Above, and Abroad," Library of Congress, accessed April 14, 2025, https://www.loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=dd7066901d6b4abfa80af089646b37a9&bookmark=The%20View%20from%20Afar.

Zavala Guillen, Ana Laura. "Feeling/Thinking the Archive: Participatory Mapping Marronage." Area 55 (2023): 416–425, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12869.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Katherine McKittrick, "On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place," Social & Cultural Geography, 2011, 12: 948. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Matthew H. Edney, 2019. Cartography: The Ideal and its History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 1. |

| 3. | Caio Figueiredo Fernande Adan and Iris Kantor, A cartografia de um oficial pintor de mapas liberto: Estudo de atribuição de autoria (Bahia-Brasil, século XIX). In 8a SIAHC Siímposio Ibero americano de História de Cartografía/O mapa como elemento de ligação cultural entre a América e a Europa. Edited by Carme Montaner and Carla Lois. Barcelona: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya, 2012) 120–33. |

| 4. | Sandra Harvey, "Unsettling Diasporas: Blackness and the Spectre of Indigeneity," Postmodern Culture, 31: 1, 2 (2020, 2021).) |

| 5. | Miguel A. Valerio, "The pardos’ triumph: The use of festival material culture for socioracial promotion in eighteenth-century Pernambuco," Journal of Festive Studies 3:49, 2021. |

| 6. | Tatiana Reinoza, Reclaiming the Americas: Latinx Art and the Politics of Territory (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2023): 18. |

| 7. | Sumathi Ramaswamy, 2014. Maps, Mother/Goddesses, and Martyrdom in Modern India. In Empires of Vision: A Reader. Edited by Martin Jay and Sumathi Ramaswamy (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014): 420. |

| 8. | Chérie N. Rivers, To Be Nsala’s Daughter: Decomposing the Colonial Gaze (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022) 31. |