Overview

In this excerpt from Patchwork Freedoms: Law, Slavery, and Race beyond Cuba's Plantations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022), Adriana Chira draws on understudied archives to chart a new history of Black rural geography and popular legalism in nineteenth-century Cuba. Long before residents of Cuba protested for national independence and island-wide emancipation in 1868, it was Santiago's Afro-descendant peasants who, gradually and invisibly, laid the groundwork for emancipation.

An Excerpt from the Introduction

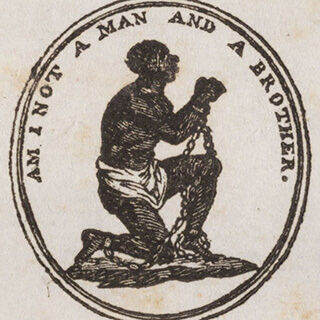

Throughout the nineteenth century, aided by railroads and steam technologies, industrial plantations expanded their footprint into ever new territories across Latin America. The timing was unique: the process occurred right as enslavement, the foundation of these enterprises, was being subjected to unprecedented challenges—from proliferating slave insurgencies to vocal liberal-abolitionist mobilization. But along industrial plantations' margins, vast and socially vibrant free rural communities of African descent made homes for themselves against many odds. Unearthing their worlds sheds light on a distinct history of emancipation that did not fully align with liberalism's trajectory, pushing us to move away from the teleological notion that modern political behaviors within Latin America were variations on their European or North American counterparts.

Across Latin America, Afro-descendant peasants took manifold paths to reach rural worlds of freedom. Some were fugitives from plantation slavery. Others had purchased their freedom in cash or through some form of service-based payments. In places like Santiago, the far eastern province of the Spanish colony of Cuba—the region which this book focuses on—many were only partially free. They had paid a portion of the price for their manumission while continuing to do some work for enslavers. Many of the free people of African descent in these kinds of communities formed families with poor white peasants living nearby. In spite of their differences and internal hierarchies, most such peasantries contended with the same looming threat: ever-expanding planter power and aspirations. As they creatively withstood or moved out of the plantations' way, they opened up and cultivated new land in forest thickets, occupying rugged landscapes traversed by unkempt dirt roads, far from major commercial centers. They bartered and sold the surplus they made in small regional markets and, on occasion, also purchased enslaved people. Their lives were not circumscribed by the plantation's logics, nor by a rigid Black/white divide, even though they contended with both of these forces.

Throughout the nineteenth century, industrial sugar production in Cuba remained centered in the west-central parts of the island, leaving Santiago, home to some relatively small and economically anemic coffee plantations, in a sort of marginal space. Santiago was close enough to be subjected to some of the same policies as the plantation-dominated regions, but far enough to escape many of the socioracial logics that defined sugar plantation communities. These kinds of peripheral communities of free people of African descent, living in the shadows of the plantation (or other regimes of intense slavery-based extraction), could be found, beyond eastern Cuba, throughout Latin America, including rural parts of Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, the Pacific lowlands of Colombia, parts of Brazilian Amazonia, and peripheries of the coffee belt in the Brazilian southeast.1Anne Eller, We Dream Together: Dominican Independence, Haiti, and the Fight for Caribbean Freedom (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); Claudia Leal, Landscapes of Freedom: Building a Postemancipation Society in the Rainforests of Western Colombia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018); Oscar de la Torre, The People of the River: Nature and Identity in Black Amazonia, 1835–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Rosa Carasquillo, Our Landless Patria: Marginal Citizenship and Race in Caguas, Puerto Rico, 1880–1910 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), chapter 1; Lowell Gudmundson and Justin Wolfe, eds., Blacks and Blackness in Central America: Between Race and Place (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Hebe Maria Mattos, Das cores do silêncio: os significados da liberdade no sudeste escravista, Brasil século XIX, 3rd ed. (Campinas, Brazil, 2013 [1995]). For work that shows how access to legal process could be limited in some such areas, see Yesenia Barragan, Freedom's Captives: Slavery and Gradual Emancipation on the Colombian Black Pacific (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021) and "Commerce in Children: Slavery, Gradual Emancipation, and the Free Womb Trade in Colombia," The Americas 78.2 (2021): 229–257. Historians have used the notion of "the peasant breach" to capture the emergence of a class of free rural cultivators out of slavery with relatively ambiguous land ownership rights. This book builds and expands on this work by focusing on the legal dynamics within such peasant communities. Among others, Ciro Flamarion Cardoso, "The Peasant Breach in the Slave System: New Developments in Brazil," Luso-Brazilian Review 25.1 (1988): 49–57; Flavio dos Santos Gomes and João José Reis, eds., Freedom by a Thread: The History of Quilombos in Brazil (New York: Diasporic Africa Press, 2016); Sidney Mintz, Caribbean Transformations (Chicago: Aldine Publishers, 1974), part II, 180–213, and "Slavery and the Rise of Peasantries," Historical Reflections 6 (1979): 213–242; Ira Berlin and Philip Morgan, eds., The Slaves' Economy: Independent Production by Slaves in the Americas (London: Routledge, 2016 [1995]); Stuart Schwartz, Slaves, Peasants, and Rebels: Reconsidering Brazilian Slavery (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), chapters 2 and 3; David Wheat, Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570–1640 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), chapter 5. On the United States and with a focus on legal consciousness as well, Dylan Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

Looking at a community such as Santiago shows that the plantation was not the only space that defined the Black experience in the Americas. It also helps bring to light other homes for Black freedom beyond well-studied Atlantic port cities.2On Cuba as an island with two histories, one around plantations and another one, beyond, Juan Pérez de la Riva, El barracón: esclavitud y capitalismo en Cuba (Barcelona: Editorial Crítica, 1978), 169–179. This model, however, assumes that there was only one alternative to sugar—one based on livestock production. On a region of Cuba centered on tobacco, in Vuelta Abajo, see William A. Morgan, "Opportunities and Boundaries for Slave Family Formation: Tobacco Labor and Demography in Pinar del Río, Cuba, 1817–1886," CLAR 29.1 (2020): 139–160. A reflexive piece that considers how sugar's ascent has shaped history writing within Cuba, with most categories of analysis emerging out of the study of sugar plantations, is Alejandro de la Fuente, "Apuntes sobre la historiografía de la segunda mitad del siglo XVI cubano," Santiago 71 (1988): 59–118. On the importance of local/regional history and on the impossibility of subsuming Santiago's trajectory to that of sugar planting and of Havana, see Julio LeRiverend, "De la historia provincial y local en sus relaciones con la historia general de Cuba," Santiago 46 (1982): 121–136. The historiography on urban free populations of color is vast. A sample that captures the breadth of this field appears in Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury, eds., The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013); Whitney Nell Stuart and John Garrison Marks, eds., Race and Nation in the Age of Emancipations (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018); special issue "Urban Slavery in the Age of Abolition," ed. Karwan Fatah-Black, IRSH 65 (2020). The inner workings of such rural worlds during the nineteenth century also suggest that attention to liberal abolitionism, nation-centered emancipation and citizenship struggles, or Atlantic abolitionist circulations leaves out another, perhaps less spectacular history of freedom whose protagonists were families, women, and children of African descent who stayed in place and forged locally focused communities. In these corners of Latin America, the nineteenth century was a time of freedom through custom. Here, people operated in a locally grounded legal sphere that consisted of orally negotiated rights, obligations, and social expectations that had the thinnest foundations in written (positive) law. Custom belonged to community justice; its versatility blurred the boundaries between formal and informal law, between legal experts and ordinary litigants, between courts, the governor's office, and hamlets tucked away in forest thickets in the interior. Its logics defied the notion that individuals were entitled to certain rights for life and could carry them across contexts. Instead, within custom-dominated worlds, legal prerogatives were distributed with an eye to local political hierarchies, economic conditions, and reputations. They could be suspended and reassigned.

In the Age of Emancipation, in places like Santiago, free or semi-free Afro-descendant peasantries led a political revolution through custom-centered community justice that remained barely visible to the authorities at the time and, in the long term, even to historians. These peasants did not rely primarily on liberal ideologies of universal freedom, individual autonomy, or notions of inclusive citizenship within national republics, even though on occasion they did invoke them. They did not wait for liberal-nationalist elites to form coalitions with them and to decree freedom from above. Instead, inside courts of law, they usually sought relief in the custom-centered colonial legal framework. In Santiago, these popular legal practices began as far back as the sixteenth century, but became especially active during the nineteenth century, when, for a range of political and economic reasons, manumission rates increased. Day in and day out, enslaved people chipped away at enslavers' authority locally, by negotiating the terms of their manumission and land access. They pulled one another out of plantation slavery gradually, yet consistently, forging communities whose members also played an important role inside courts of law as witnesses, advocates, or bystanders when conflicts arose. Within rural spaces like Santiago that were marked by relative underdevelopment, Afro-descendant peasants creatively defined manumission-based freedoms piece by piece through mundane social practices that had little grounding in positive law, were orally negotiated, and were recognized by local governors and courts of justice. These freedoms were patchwork, often incomplete when measured against liberal-abolitionist yardsticks, precarious, and even reversible. Yet they were very concrete, and in the long term, they served to corrode the legal structures of plantation slavery locally.

In Santiago's musty rooms and busy antechambers, as elsewhere in Latin America, magistrates and litigants puzzled out enslaved people's rights of access to autonomy, property, and family, case by case. Would a woman who had purchased her freedom while pregnant give birth to an enslaved or to a free child? Could enslaved people who had paid half the price of their freedom spend the night with kin living on other properties? To whom did a pig truly belong, the enslaver on whose estate it roamed, or the enslaved who had purchased it with her savings and had tended to it? Could enslaved and free people of color occupy fallow land inside private estates? In Santiago, such claims were not apparently too small to be assessed and extensively documented by local scribes, notaries, and other legal officers. The freedom that such adjudications yielded had a plurality of meanings, some of them contradictory and akin to subordination and dependence. Scholars of the early modern Atlantic world have shown that vernacular understandings of freedom were highly diverse in social practice, going beyond abstract written definitions embedded in legislation.3On manumission-based Black freedom, among others, Erica Ball, Tatiana Seijas, and Terri Snyder, eds., As If She Were Free: A Collective Biography of Women and Emancipation in the Americas (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Mariana Dantas, Black Townsmen: Urban Slavery and Freedom in the Eighteenth-Century Americas (London: Palgrave, 2008); Mariana Dantas and Douglas Libby, "Families, Manumission, and Freed People in Urban Minas Gerais in the Era of Atlantic Abolitionism," IRSH 65 (2020): 117–144; Erika Denise Edwards, Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2020); Zephyr Frank, Dutra's World: Wealth and Family in Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004); Oilda Hevia Lanier and Daisy Rubiera Castillo, Emergiendo del silencio: mujeres negras en la historia de Cuba (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2016); Lyman Johnson, "Manumission in Colonial Buenos Aires, 1776–1810," HAHR (1979): 258–279; Michelle McKinley, Fractional Freedoms: Slavery, Intimacy, and Legal Mobilization in Colonial Lima, h600–h700 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016); Aisnara Perera and María de los Angeles Meriño Fuentes, Para librarse de lazos, antes buena familia que buenos brazos: apuntes sobre la manumisión en Cuba (Santiago: Editorial Oriente, 2009). Beyond the Iberian Atlantic, among others, Randy Sparks and Rosemary Brana-Shute, eds., Paths to Freedom: Manumission in the Atlantic World (Charleston: University of South Carolina Press, 2009); Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020); Bernard Moitt, Women and Slavery in the French Antilles, 1635–1848 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001); Judith Shafer, Becoming Free, Remaining Free: Manumission and Enslavement in New Orleans, 1846–1862 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003) Within Spanish America, such pluralism did not operate in parallel or at odds with the law; it was part of custom and as such ensconced in the law.4Scholars of law and slavery in American slave societies have emphasized the importance of considering law broadly, beyond the written, to include litigation and petitioning of higher authorities. Such an approach makes visible the participation of subaltern groups in the legal system as well as the plurality of their understandings of law and freedom. This literature is vast. Among others, focusing on Latin America, Manuel Barcia, "'Fighting with the Enemy's Weapons: The Usage of the Colonial Legal Framework by Nineteenth-Century Cuban Slaves,'" Atlantic Studies 3.2 (2006): 159–181; Herman Bennett, Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570–1640 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003); Sherwin Bryant, "Enslaved Rebels, Fugitives, and Litigants: The Resistance Continuum in Colonial Quito," CLAR 13 (2004): 7–46; Camillia Cowling, Conceiving Freedom: Women of Color, Gender, and the Abolition of Slavery in Havana and Rio de Janeiro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Alejandro de la Fuente and Ariela Gross, Becoming Free, Becoming Black: Race, Freedom, and Law in Cuba, Virginia, and Louisiana (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Keila Grinberg, "Freedom Suits and Civil Law in Brazil and the United States," Slavery & Abolition 22.3 (2001): 66–82; Chloe Ireton, "Black Africans and Freedom Litigation Suits to Define Just War and Just Slavery in the Early Spanish Empire," Renaissance Quarterly 73 (2020): 1–43; McKinley, Fractional Freedoms; Brian Owensby, "How Juan and Leonor Won Their Freedom: Litigation and Liberty in Seventeenth-Century Mexico," HAHR 85 (2005): 39–79; Aisnara Perera Díaz and María de los Ángeles Meriño Fuentes, Estrategias de libertad: un acercamiento a las acciones legales de los esclavos en Cuba (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2015), 2 vols.; Bianca Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial: Ordinary Litigants and Colonialism in the Spanish Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017) and Children of the Father King: Youth, Authority, and Legal Minority in Colonial Lima (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Frank Proctor III, "Damned Notions of Liberty": Slavery, Culture, and Power in Colonial Mexico, 1640–1769 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011); Rebecca Scott and Carlos Venegas, "María Coleta and the Capuchin Friar: Slavery, Salvation, and the Adjudication of Status," WMQ 76.4 (2019): 727–762; Aurora Vergara Figueroa and Carmen Luz Cosme, Demando mi libertad: mujeres negras y sus estrategias de resistencia en la Nueva Granada, Venezuela y Cuba, 1700–1800 (Cali, Colombia: Editorial Universidad Icesi, 2018). Beyond Latin America, Mariana Candido, "African Freedom Suits and Portuguese Vassal Status: Legal Mechanisms for Fighting Enslavement in Benguela, Angola, 1800–1830," Slavery & Abolition 32.3 (2011): 447–459; Roquinaldo Ferreira, Cross-Cultural Exchange in the Atlantic World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), chapter 3; Ariela Gross, Double Character: Slavery and Mastery in the Antebellum Southern Courtroom (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Kimberly Welch, Black Litigants in the Antebellum American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Historians have explored the role of community justice before the rise of modern legal systems, emphasizing local variations, the role of vernacular understandings of justice, and of social and kinship relations associated with personal reputation. Among others, Tommaso Astarita, Village Justice: Community, Family, and Popular Culture in Early Modern Italy (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); Laura Edwards, The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); Daniel Lord Smail, The Consumption of Justice: Emotion, Publicity, and Legal Culture in Marseille, 1264–1423 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003).

That custom could hold any emancipatory power is by many measures surprising. Within the Spanish colonial tradition, uso y costumbres ("usage and customs") had historically referred to continuity and tradition. This meant that locally negotiated values enabled a population divided by the hierarchies of birth status to coalesce around a tenuous legal-cultural consensus, known as "the peace." For centuries, jurists and state-makers across the Iberian Atlantic had relied on custom to prevent challenges to entrenched hierarchies or, in early modern juridical language, to keep "the peace" ("buen gobierno," "la paz").5Víctor Tau Anzoátegui, El poder de la costumbre: estudios sobre el derecho consuetudi-nario en América hispana hasta la emancipación (Buenos Aires: Instituto de Investigaciones de Historia de Derecho, 2001).

Birth right status structured the distribution of legislated rights in colonial Latin America; certain lineages who controlled power locally could also shape access to customary rights for all. But beyond the imperative of birth status protections, the law also had to manage conflict, which local authorities usually did through custom. State institutions could temper local elites' powers in the name of "the peace."6Other scholars of law and slavery who have pointed out how enslaved people maneuvered prudence-based legal systems beyond the Iberian Atlantic are Edwards, The People and Their Peace; Malik Ghachem, The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Edward Ruggemer, Slave Law and the Politics of Resistance in the Early Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). In Santiago, enslaved people invoked the specter of marronage (the action of fleeing slavery) and insurrection to get their way with local institutions and elites and shape law-making; the distinction between the judicial and extra-judicial was therefore not so clear-cut. As one enslaver remarked, enslaved people were more likely to file freedom suits when fears of marronage were rampant among planters.7ANC, ASC, leg. 582, exp. 13,348, "El Síndico Procurador reclama la libertad de la esclava Gertrudis de Madame Fillet Barberousse, 1833." Whether or not the assessment was accurate, it nevertheless suggests that some people with power saw a connection between these two avenues toward freedom. As a result of these related tactics, whether their connections were real or imagined, subaltern sectors of society might be circumstantially permitted to occupy land on privately owned estates. Enslaved people might be granted time off to tend to a vegetable garden, or they might be permitted to purchase their freedom in installments or conditionally, including in return for certain services. To judges' and governors' minds, such equity-based rulings placated the poor and maximized their political utility, since they could then be mobilized as vassals.8 On casuistic (case-by-case) decision-making as a form of equity-based judgment, Recopilación de Leyes de los Reynos de las Indias (Madrid: Imprenta de la viuda de Joaquín Ibarra, 1791 [1680]), Libro II, Titl. I, Law XXIV, 1:223; Códigos Españoles. Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España, Libro III, Tit. IV, Law IV (Madrid: Imprenta de la Publicidad, 1850), 2:16. Also, Antonio Manuel Hespanha, Poder e instituçoes no antigo regime: guia de estudo (Lisbon: Cosmos, 1992), 20–35, and Como os juristas viam o mundo (Lisbon, 2015), 407–424; Tamar Herzog, Upholding Justice: Society, State, and the Penal System in Quito (h650–h750) (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004); Brian Owensby, Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), chapter 3; Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial; Víctor Tau Anzoátegui, Casuismo y sistema: indagación sobre el espiritu del derecho indiano (Buenos Aires: IIHD, 1992); Jesús Vallejo, "Power Hierarchies in Medieval Juridical Thought," Ius commune 19 (1992): 1–29; Joaquín Escriche, Diccionario razonado de legislación y jurisprudencia (Madrid: Imprenta del Colegio Nacional de Sordomudos, 1838), vol. 1, under arbitrio de juez, 325, and vol. 2 (Madrid: Libreria de la Señora Viuda de D. Antonio Oleja, 1847), under equidad, 833–834; Alejandro Guzmán-Brito, Codificación del derecho civil interpretación de las leyes (Madrid: Iustel, 2011), 188–221. Enslaved people had the right to be protected against bodily harm, including hunger. Access to a vegetable garden, an equity-based right, was considered as the satisfaction of such a subsistence right. P. IV, Titl. XXI, Law VI, Los Códigos Españoles. El Código de Las Siete Partidas (Madrid: Imprenta de la Publicidad, 1850), 2:519. On legal actions and marronage as elements of a spectrum of related strategies, rather than as independent tactics, Bryant, "Enslaved Rebels, Fugitives, and Litigants" and Rivers of Gold, Lives of Bondage: Governing through Slavery in Colonial Quito (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014). These kinds of subsistence rights acquired the weight of custom if exercised over a long period of time. They were more likely in areas where the local elite had a tenuous grip on power. Both Africans and Afro-descendants accessed them and fought for them through the courts, a relatively remarkable phenomenon—in light of the documented difficulty that many Africans had to access courts of law in other parts of Latin America.9Mary Karasch, Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, h800–h850 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987).

The practice of allocating rights to enslaved people according to custom—a practice that had existed for hundreds of years in Santiago and elsewhere in Latin America—was not intended to be a liberating act. Indeed, its primary goal was simply to release some of the tensions inherent in birth status hierarchies and slavery, all the while promoting conformity among the enslaved. By the eighteenth century, however, in certain parts of Latin America, some such custom-based openings did hold destabilizing power. This was due to the fact that, more and more, subaltern groups began to claim customary entitlements not just in the name of need but also in the name of merit, and against a background of increasingly vocal abolitionist demands in the Atlantic world. Across Latin America, as manumission became more frequent, so did conflict and debate about its workings. When freedom litigants invoked custom, they often pointed to recently established expectations associated with relations of debt and reciprocation. These customs were less akin to tradition, and more similar to contracts—arrangements that were supposed to reward the parties for their respective contributions to an exchange. Contractual logics therefore became increasingly pervasive in rural Santiago as manumission rates increased. That customary relations could be contractual held politically combustible potential at a time of hemispheric liberal rhetoric emphasizing individual labor rights over fixed birth status. Without a doubt, this particular understanding of custom might have gained greater prominence inside courts of law in the nineteenth century precisely under liberal influences.

Yet, when African and Afro-descendant peasants approached contract-like relations as custom, they also tapped into a second definition of it from within the colonial legal tradition: as an expression of "popular will" and traditions of distributing rights based on individual reputation and political utility, not just lineage.10Bianca Premo, "Custom Today: Temporality, Customary Law, and Indigenous Enlightenment," HAHR 94.3 (2014): 355–379, esp. 359; Paola Miceli, Derecho con-suetudinario y memoria: práctica jurídica y costumbre en Castilla y León (siglos XI–XIV) (Madrid: Universidad Carlos III, 2012); Yanna Yannakakis, The Art of Being In-Between: Native Intermediaries, Indian Identity and Local Rule in Colonial Oaxaca (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 119, 123. Though vague, the notion of a "popular will" reflected on local custom's power to metamorphose based on circumstances, to be closer to local realities than positive law, and to unmoor power distribution from birth status, lineage, and tradition.11Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial. By this token, manumission and its locally specific transactional logics triggered, in the words of Michelle McKinley, "ripples of activity"—its legalities were not "frozen."12McKinley, Fractional Freedoms, 168. Such activity accelerated in the nineteenth century, butting against fixed status increasingly more.

While freedom as a liberal-abolitionist artifact and freedom as custom might have evolved in parallel and occasionally intersected, they nevertheless did differ in important respects. The world of customary freedom had plural meanings that arose through practice: the securing of that freedom and its meanings were part of the same process. By contrast, the legal meanings of liberal freedom were far more standardized and abstract because more strictly embedded in written law or liberal manifestos. Customary freedom was also centered on families and on extended networks of support and obligations. Freed people often remained entangled in such obligations after obtaining their manumission, in ways that limited their mobility and choices.13On the precarity of manumission-based freedom, Sidney Chalhoub, "The Precariousness of Freedom in a Slavery Society (Brazil in the Nineteenth Century)," IRSH 56.3 (2011): 405–439; Rebecca Scott and Jean Hébrard, Freedom Papers: An Atlantic Odyssey in the Age of Emancipation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014). In areas with large free populations of color, individuals who were lateral to the enslave—enslaved relationship—the mothers, fathers, siblings, lovers, neighbors of the manumitted—also informed individual experiences of freedom. Dynamics and hierarchies internal to Afro-descendent communities formed the foundation for manumission's legalities. Belonging to such communities, rather than having autonomy, determined what rights one could acquire locally, an undoubtedly fractious process that yielded hierarchies.

The adjudication of free status (as reputation) through the community also informed popular racial thinking at a key historical moment in the history of racial ideologies in Cuba—the mid-nineteenth century. In Santiago, the peasantry used the language of color to describe free status and local hierarchies. As elsewhere, and as other scholars of Latin America have long pointed out, color status was not fixed but, rather, depended on one's actions and locally defined merits and reputation.14Ben Vinson III, "Introduction: African (Black) Diaspora History, Latin American History," The Americas 63.1 (2006): 1–18, and Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018); María del Carmen Baerga, Negociaciones de sangre: dinámicas racializantes en el Puerto Rico decimonónico (San Juan: Ediciones Callejón, 2015); Douglas Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico (1660–1720) (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994); María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008); Víctor Goldgel Carballo, "El fantasma de la raza: simulación, caricaturas y cosméticos en la Cuba del siglo XIX," in Miradas efímeras. Cultura visual en el siglo XIX, ed. Cecilia Rodríguez Lehmann and Nathalie Buzaglo (Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuartopropio, 2017), 177–195; Karen Morrison, Cuba's Racial Crucible: The Sexual Economy of Social Identities, 1750–2000 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), chapter 4. The point here is not to rediscover the malleability of race in Latin America. It is, rather, to unearth its politics within a specific context and to offer a method for accessing popular forms of racial thinking that did not gain expression in print culture or in elite political manifestos of the time. Indeed, it is to show that racial thinking was fundamentally entwined with manumission as a process. The state itself had allowed for some malleability of official color taxonomies prudentially. Somewhat privileged people of African descent, who had access to household dependents and enslaved people, questioned official Black/white distinctions in this colonial society before the rise of well-known intellectual theories of whitening or of the well-known ideology of "racial confraternity," such as José Martí's.15On nineteenth-century ideologies and practices of whitening in Latin America, George Reid Andrews, Los afroargentinos de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor, 1989 [1980]) and Blacks and Whites in São Paulo, Brazil, 1888–1988 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 54–89; Dain Borges, "'Puffy, Ugly, Slothful, and Inert': Degeneration in Brazilian Thought, 1880–1940," Journal of Latin American Studies 25.2 (1993): 235–256; Erika Denise Edwards, Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2020); Nancy Leys Stepan, The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991); Winthrop Wright, Café con leche: Race, Class, and National Image in Venezuela (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013); Laura Gotkowitz, ed., Histories of Race and Racism: The Andes and Mesoamerica from Colonial Times to the Present (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), especially Parts II and III. Some people lost association with official terms denoting Blackness in the record, all the while their African ancestry was still widely known. They did so, however, without direct knowledge of liberal-intellectual elites' theories of whitening, but rather through local reputational politics. Yet this reconceptualization of status was not so radical. The local elite peasant class still operated within the boundaries of a hierarchical system bearing slavery's imprint. Birth status mattered: Africanness and genealogical proximity to slavery (when one and one's ancestors had been manumitted) were considered a stigma. One's upward mobility depended on the acquisition of retainers, including enslaved people, and therefore on domination. These popular understandings of color status did not necessarily coalesce into a larger current. But Santiago's case proves another point that scholars of Latin America have shown: that popular racial ideologies were regionally specific, because, I argue, rooted in local legal customs of manumission.16Paulina Alberto, Terms of Inclusion: Black Intellectuals in Twentieth-Century Brazil (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011); Nancy Appelbaum, Muddied Waters: Race, Region, and Local History in Colombia, 1846–1948 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Sarah Chambers, From Subjects to Citizens: Honor, Gender, and Politics, Peru, h780–h854 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999); Barbara Weinstein, The Color of Modernity: São Paulo and the Making of Race and Nation in Brazil (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

By mid-century, custom-based entitlements fueled political expectations, as the plantation's footprint expanded into Afro-descendant pea-santries' lands and prerogatives. Through legal reforms, planters and state officials in the Spanish Empire, like their counterparts in Brazil, moved to reduce custom's presence in the courtrooms and replace it with positive law.17Among others, Pedro Cantisano and Mariana Armond Dias Paes, "Legal Reasoning in a Slave Society (Brazil, 1860–1888)," LHR 36 (2018): 471–510; Sidney Chalhoub, "The Politics of Ambiguity: Conditional Manumission, Labor Contracts, and Slave Emancipation in Brazil (1850–1888)," IRSH 60 (2015): 161–191; Keila Grinberg, "Slavery, Liberalism, and Civil Law: Definitions of Status and Citizenship in the Elaboration of the Brazilian Civil Code (1855–1916)," in Honor, Status, and Law in Modern Latin America, ed. Sueann Caulfield, Sarah C. Chambers, and Lara Putnam (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 109–130. They wrote down some customs that helped the enslaved, likely knowing that the end of the institution of slavery was in sight and that some such rights would facilitate (from their vantage point) a less conflictive transition to general emancipation. At the same time, the policy of turning custom into legislation eroded local autonomy, crucial to Afro-descendant peasant communities, while placing more control in the hands of legal experts and outside creditors who sought uniform legal contexts. Many enslaved people who had negotiated manumission with their enslavers lost ground when they needed to litigate to enforce the terms of those negotiations because judges could no longer recognize customary arrangements and rights; they had to restrict themselves to enforcing strictly the letter of positive law.

In 1868, eastern Cuba's enslaved and free people of African descent rose up in arms against the attacks on their autonomy and land access. They joined a white liberal elite that had initiated a war of independence against Spain. The Afro-descendant peasantry shaped the goals of this thirty-year-long mobilization (1868–1878, 1879–1880, 1895–1898) to include, beyond national liberation, also general emancipation and racially inclusive citizenship rights.18Carmen Barcia, Burguesía esclavista y abolición (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1987); Ada Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999); Bonnie A. Lucero, Revolutionary Masculinity and Racial Inequality (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018); Emilio Roíg de Leuchsenring, La guerra libertadora cubana (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 1952). Their support of general emancipation had likely developed out of their earlier efforts to undermine plantation slavery through manumission, the court system, and the customary sphere. Some of the ideological fires driving the three Cuban wars of independence—one of the epic moments of Black liberation in the Western Hemisphere—were kindled by the sense of political entitlement to local autonomy that had emerged through regionally grounded community justice and manumission.

About the Author

Adriana Chira is an assistant professor of history at Emory University. She is the author of Patchwork Freedoms: Law, Slavery, and Race beyond Cuba's Plantations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022). Her second project, tentatively titled In the Plantations' Shadows: Black Peasants and Land Ownership by Possession in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Spanish Equatorial Guinea, 1880–1960, explores a mode of land tenure that many rural communities transitioning from slavery to freedom relied on to subsist. Patchwork Freedoms won the American Historical Association's 2023 Rawley Prize "for outstanding historical writing that explores aspects of integration of Atlantic worlds before the twentieth century.”

Recommended Resources

Text

Barcia, Manuel. "'Fighting with the Enemy's Weapons: The Usage of the Colonial Legal Framework by Nineteenth-Century Cuban Slaves,'" Atlantic Studies 3.2 (2006): 159–181.

Chira, Adriana. Uneasy Intimacies: Race, Family, and Property in Santiago de Cuba, 1803–1868. PhD diss. University of Michigan, 2016. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/120651/achira_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Ferrer, Ada. Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

Fuente, Alejandro de la and Ariela Gross, Becoming Free, Becoming Black: Race, Freedom, and Law in Cuba, Virginia, and Louisiana (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Garth, Hannah. "There is No Race in Cuba": Level of Culture and the Logics of Transnational Anti-Blackness." Anthropological Quarterly 94, no. 3. 2021: 385–410.

Lucero, Bonnie. Revolutionary Masculinity and Racial Inequality: Gendering War and Politics in Cuba (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018).

Reid-Vazquez, Michele. The Year of the Lash: Free People of Color in Cuba and the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Web

"Archaeological Landscape of the First Coffee Plantations in the South-East of Cuba." Unesco: World Heritage Convention. 2000. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1008/.

"Cuba: History and Culture: Cuban Archives at Yale." Yale Library (New Haven, CT). Accessed August 23, 2022. https://guides.library.yale.edu/c.php?g=711233&p=5060445.

Cuban Slavery Documents collection, 1820–1892. John Hay Library, University Archives and Manuscripts, Brown University (Providence, RI). 2016. https://www.riamco.org/render?eadid=US-RPB-ms2014.018&view=title.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Anne Eller, We Dream Together: Dominican Independence, Haiti, and the Fight for Caribbean Freedom (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); Claudia Leal, Landscapes of Freedom: Building a Postemancipation Society in the Rainforests of Western Colombia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018); Oscar de la Torre, The People of the River: Nature and Identity in Black Amazonia, 1835–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Rosa Carasquillo, Our Landless Patria: Marginal Citizenship and Race in Caguas, Puerto Rico, 1880–1910 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), chapter 1; Lowell Gudmundson and Justin Wolfe, eds., Blacks and Blackness in Central America: Between Race and Place (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Hebe Maria Mattos, Das cores do silêncio: os significados da liberdade no sudeste escravista, Brasil século XIX, 3rd ed. (Campinas, Brazil, 2013 [1995]). For work that shows how access to legal process could be limited in some such areas, see Yesenia Barragan, Freedom's Captives: Slavery and Gradual Emancipation on the Colombian Black Pacific (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021) and "Commerce in Children: Slavery, Gradual Emancipation, and the Free Womb Trade in Colombia," The Americas 78.2 (2021): 229–257. Historians have used the notion of "the peasant breach" to capture the emergence of a class of free rural cultivators out of slavery with relatively ambiguous land ownership rights. This book builds and expands on this work by focusing on the legal dynamics within such peasant communities. Among others, Ciro Flamarion Cardoso, "The Peasant Breach in the Slave System: New Developments in Brazil," Luso-Brazilian Review 25.1 (1988): 49–57; Flavio dos Santos Gomes and João José Reis, eds., Freedom by a Thread: The History of Quilombos in Brazil (New York: Diasporic Africa Press, 2016); Sidney Mintz, Caribbean Transformations (Chicago: Aldine Publishers, 1974), part II, 180–213, and "Slavery and the Rise of Peasantries," Historical Reflections 6 (1979): 213–242; Ira Berlin and Philip Morgan, eds., The Slaves' Economy: Independent Production by Slaves in the Americas (London: Routledge, 2016 [1995]); Stuart Schwartz, Slaves, Peasants, and Rebels: Reconsidering Brazilian Slavery (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), chapters 2 and 3; David Wheat, Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570–1640 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), chapter 5. On the United States and with a focus on legal consciousness as well, Dylan Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). |

|---|---|

| 2. | On Cuba as an island with two histories, one around plantations and another one, beyond, Juan Pérez de la Riva, El barracón: esclavitud y capitalismo en Cuba (Barcelona: Editorial Crítica, 1978), 169–179. This model, however, assumes that there was only one alternative to sugar—one based on livestock production. On a region of Cuba centered on tobacco, in Vuelta Abajo, see William A. Morgan, "Opportunities and Boundaries for Slave Family Formation: Tobacco Labor and Demography in Pinar del Río, Cuba, 1817–1886," CLAR 29.1 (2020): 139–160. A reflexive piece that considers how sugar's ascent has shaped history writing within Cuba, with most categories of analysis emerging out of the study of sugar plantations, is Alejandro de la Fuente, "Apuntes sobre la historiografía de la segunda mitad del siglo XVI cubano," Santiago 71 (1988): 59–118. On the importance of local/regional history and on the impossibility of subsuming Santiago's trajectory to that of sugar planting and of Havana, see Julio LeRiverend, "De la historia provincial y local en sus relaciones con la historia general de Cuba," Santiago 46 (1982): 121–136. The historiography on urban free populations of color is vast. A sample that captures the breadth of this field appears in Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury, eds., The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013); Whitney Nell Stuart and John Garrison Marks, eds., Race and Nation in the Age of Emancipations (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018); special issue "Urban Slavery in the Age of Abolition," ed. Karwan Fatah-Black, IRSH 65 (2020). |

| 3. | On manumission-based Black freedom, among others, Erica Ball, Tatiana Seijas, and Terri Snyder, eds., As If She Were Free: A Collective Biography of Women and Emancipation in the Americas (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Mariana Dantas, Black Townsmen: Urban Slavery and Freedom in the Eighteenth-Century Americas (London: Palgrave, 2008); Mariana Dantas and Douglas Libby, "Families, Manumission, and Freed People in Urban Minas Gerais in the Era of Atlantic Abolitionism," IRSH 65 (2020): 117–144; Erika Denise Edwards, Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2020); Zephyr Frank, Dutra's World: Wealth and Family in Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004); Oilda Hevia Lanier and Daisy Rubiera Castillo, Emergiendo del silencio: mujeres negras en la historia de Cuba (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2016); Lyman Johnson, "Manumission in Colonial Buenos Aires, 1776–1810," HAHR (1979): 258–279; Michelle McKinley, Fractional Freedoms: Slavery, Intimacy, and Legal Mobilization in Colonial Lima, h600–h700 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016); Aisnara Perera and María de los Angeles Meriño Fuentes, Para librarse de lazos, antes buena familia que buenos brazos: apuntes sobre la manumisión en Cuba (Santiago: Editorial Oriente, 2009). Beyond the Iberian Atlantic, among others, Randy Sparks and Rosemary Brana-Shute, eds., Paths to Freedom: Manumission in the Atlantic World (Charleston: University of South Carolina Press, 2009); Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020); Bernard Moitt, Women and Slavery in the French Antilles, 1635–1848 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001); Judith Shafer, Becoming Free, Remaining Free: Manumission and Enslavement in New Orleans, 1846–1862 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003) |

| 4. | Scholars of law and slavery in American slave societies have emphasized the importance of considering law broadly, beyond the written, to include litigation and petitioning of higher authorities. Such an approach makes visible the participation of subaltern groups in the legal system as well as the plurality of their understandings of law and freedom. This literature is vast. Among others, focusing on Latin America, Manuel Barcia, "'Fighting with the Enemy's Weapons: The Usage of the Colonial Legal Framework by Nineteenth-Century Cuban Slaves,'" Atlantic Studies 3.2 (2006): 159–181; Herman Bennett, Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570–1640 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003); Sherwin Bryant, "Enslaved Rebels, Fugitives, and Litigants: The Resistance Continuum in Colonial Quito," CLAR 13 (2004): 7–46; Camillia Cowling, Conceiving Freedom: Women of Color, Gender, and the Abolition of Slavery in Havana and Rio de Janeiro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Alejandro de la Fuente and Ariela Gross, Becoming Free, Becoming Black: Race, Freedom, and Law in Cuba, Virginia, and Louisiana (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Keila Grinberg, "Freedom Suits and Civil Law in Brazil and the United States," Slavery & Abolition 22.3 (2001): 66–82; Chloe Ireton, "Black Africans and Freedom Litigation Suits to Define Just War and Just Slavery in the Early Spanish Empire," Renaissance Quarterly 73 (2020): 1–43; McKinley, Fractional Freedoms; Brian Owensby, "How Juan and Leonor Won Their Freedom: Litigation and Liberty in Seventeenth-Century Mexico," HAHR 85 (2005): 39–79; Aisnara Perera Díaz and María de los Ángeles Meriño Fuentes, Estrategias de libertad: un acercamiento a las acciones legales de los esclavos en Cuba (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2015), 2 vols.; Bianca Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial: Ordinary Litigants and Colonialism in the Spanish Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017) and Children of the Father King: Youth, Authority, and Legal Minority in Colonial Lima (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Frank Proctor III, "Damned Notions of Liberty": Slavery, Culture, and Power in Colonial Mexico, 1640–1769 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011); Rebecca Scott and Carlos Venegas, "María Coleta and the Capuchin Friar: Slavery, Salvation, and the Adjudication of Status," WMQ 76.4 (2019): 727–762; Aurora Vergara Figueroa and Carmen Luz Cosme, Demando mi libertad: mujeres negras y sus estrategias de resistencia en la Nueva Granada, Venezuela y Cuba, 1700–1800 (Cali, Colombia: Editorial Universidad Icesi, 2018). Beyond Latin America, Mariana Candido, "African Freedom Suits and Portuguese Vassal Status: Legal Mechanisms for Fighting Enslavement in Benguela, Angola, 1800–1830," Slavery & Abolition 32.3 (2011): 447–459; Roquinaldo Ferreira, Cross-Cultural Exchange in the Atlantic World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), chapter 3; Ariela Gross, Double Character: Slavery and Mastery in the Antebellum Southern Courtroom (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Kimberly Welch, Black Litigants in the Antebellum American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Historians have explored the role of community justice before the rise of modern legal systems, emphasizing local variations, the role of vernacular understandings of justice, and of social and kinship relations associated with personal reputation. Among others, Tommaso Astarita, Village Justice: Community, Family, and Popular Culture in Early Modern Italy (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); Laura Edwards, The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); Daniel Lord Smail, The Consumption of Justice: Emotion, Publicity, and Legal Culture in Marseille, 1264–1423 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003). |

| 5. | Víctor Tau Anzoátegui, El poder de la costumbre: estudios sobre el derecho consuetudi-nario en América hispana hasta la emancipación (Buenos Aires: Instituto de Investigaciones de Historia de Derecho, 2001). |

| 6. | Other scholars of law and slavery who have pointed out how enslaved people maneuvered prudence-based legal systems beyond the Iberian Atlantic are Edwards, The People and Their Peace; Malik Ghachem, The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Edward Ruggemer, Slave Law and the Politics of Resistance in the Early Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). |

| 7. | ANC, ASC, leg. 582, exp. 13,348, "El Síndico Procurador reclama la libertad de la esclava Gertrudis de Madame Fillet Barberousse, 1833." |

| 8. | On casuistic (case-by-case) decision-making as a form of equity-based judgment, Recopilación de Leyes de los Reynos de las Indias (Madrid: Imprenta de la viuda de Joaquín Ibarra, 1791 [1680]), Libro II, Titl. I, Law XXIV, 1:223; Códigos Españoles. Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España, Libro III, Tit. IV, Law IV (Madrid: Imprenta de la Publicidad, 1850), 2:16. Also, Antonio Manuel Hespanha, Poder e instituçoes no antigo regime: guia de estudo (Lisbon: Cosmos, 1992), 20–35, and Como os juristas viam o mundo (Lisbon, 2015), 407–424; Tamar Herzog, Upholding Justice: Society, State, and the Penal System in Quito (h650–h750) (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004); Brian Owensby, Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), chapter 3; Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial; Víctor Tau Anzoátegui, Casuismo y sistema: indagación sobre el espiritu del derecho indiano (Buenos Aires: IIHD, 1992); Jesús Vallejo, "Power Hierarchies in Medieval Juridical Thought," Ius commune 19 (1992): 1–29; Joaquín Escriche, Diccionario razonado de legislación y jurisprudencia (Madrid: Imprenta del Colegio Nacional de Sordomudos, 1838), vol. 1, under arbitrio de juez, 325, and vol. 2 (Madrid: Libreria de la Señora Viuda de D. Antonio Oleja, 1847), under equidad, 833–834; Alejandro Guzmán-Brito, Codificación del derecho civil interpretación de las leyes (Madrid: Iustel, 2011), 188–221. Enslaved people had the right to be protected against bodily harm, including hunger. Access to a vegetable garden, an equity-based right, was considered as the satisfaction of such a subsistence right. P. IV, Titl. XXI, Law VI, Los Códigos Españoles. El Código de Las Siete Partidas (Madrid: Imprenta de la Publicidad, 1850), 2:519. On legal actions and marronage as elements of a spectrum of related strategies, rather than as independent tactics, Bryant, "Enslaved Rebels, Fugitives, and Litigants" and Rivers of Gold, Lives of Bondage: Governing through Slavery in Colonial Quito (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014). |

| 9. | Mary Karasch, Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, h800–h850 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987). |

| 10. | Bianca Premo, "Custom Today: Temporality, Customary Law, and Indigenous Enlightenment," HAHR 94.3 (2014): 355–379, esp. 359; Paola Miceli, Derecho con-suetudinario y memoria: práctica jurídica y costumbre en Castilla y León (siglos XI–XIV) (Madrid: Universidad Carlos III, 2012); Yanna Yannakakis, The Art of Being In-Between: Native Intermediaries, Indian Identity and Local Rule in Colonial Oaxaca (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 119, 123. |

| 11. | Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial. |

| 12. | McKinley, Fractional Freedoms, 168. |

| 13. | On the precarity of manumission-based freedom, Sidney Chalhoub, "The Precariousness of Freedom in a Slavery Society (Brazil in the Nineteenth Century)," IRSH 56.3 (2011): 405–439; Rebecca Scott and Jean Hébrard, Freedom Papers: An Atlantic Odyssey in the Age of Emancipation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014). |

| 14. | Ben Vinson III, "Introduction: African (Black) Diaspora History, Latin American History," The Americas 63.1 (2006): 1–18, and Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018); María del Carmen Baerga, Negociaciones de sangre: dinámicas racializantes en el Puerto Rico decimonónico (San Juan: Ediciones Callejón, 2015); Douglas Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico (1660–1720) (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994); María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008); Víctor Goldgel Carballo, "El fantasma de la raza: simulación, caricaturas y cosméticos en la Cuba del siglo XIX," in Miradas efímeras. Cultura visual en el siglo XIX, ed. Cecilia Rodríguez Lehmann and Nathalie Buzaglo (Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuartopropio, 2017), 177–195; Karen Morrison, Cuba's Racial Crucible: The Sexual Economy of Social Identities, 1750–2000 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), chapter 4. |

| 15. | On nineteenth-century ideologies and practices of whitening in Latin America, George Reid Andrews, Los afroargentinos de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor, 1989 [1980]) and Blacks and Whites in São Paulo, Brazil, 1888–1988 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 54–89; Dain Borges, "'Puffy, Ugly, Slothful, and Inert': Degeneration in Brazilian Thought, 1880–1940," Journal of Latin American Studies 25.2 (1993): 235–256; Erika Denise Edwards, Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2020); Nancy Leys Stepan, The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991); Winthrop Wright, Café con leche: Race, Class, and National Image in Venezuela (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013); Laura Gotkowitz, ed., Histories of Race and Racism: The Andes and Mesoamerica from Colonial Times to the Present (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), especially Parts II and III. |

| 16. | Paulina Alberto, Terms of Inclusion: Black Intellectuals in Twentieth-Century Brazil (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011); Nancy Appelbaum, Muddied Waters: Race, Region, and Local History in Colombia, 1846–1948 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Sarah Chambers, From Subjects to Citizens: Honor, Gender, and Politics, Peru, h780–h854 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999); Barbara Weinstein, The Color of Modernity: São Paulo and the Making of Race and Nation in Brazil (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). |

| 17. | Among others, Pedro Cantisano and Mariana Armond Dias Paes, "Legal Reasoning in a Slave Society (Brazil, 1860–1888)," LHR 36 (2018): 471–510; Sidney Chalhoub, "The Politics of Ambiguity: Conditional Manumission, Labor Contracts, and Slave Emancipation in Brazil (1850–1888)," IRSH 60 (2015): 161–191; Keila Grinberg, "Slavery, Liberalism, and Civil Law: Definitions of Status and Citizenship in the Elaboration of the Brazilian Civil Code (1855–1916)," in Honor, Status, and Law in Modern Latin America, ed. Sueann Caulfield, Sarah C. Chambers, and Lara Putnam (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 109–130. |

| 18. | Carmen Barcia, Burguesía esclavista y abolición (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1987); Ada Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999); Bonnie A. Lucero, Revolutionary Masculinity and Racial Inequality (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018); Emilio Roíg de Leuchsenring, La guerra libertadora cubana (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 1952). |