Overview

This excerpt, as well as the accompanying video stills, centers the activism of Bill Smith, a central figure in the founding of Georgia’s Gay Liberation Front and a member of the Southeastern Gay Coalition. Smith served as the first out-gay man in Atlanta city government as Sam Massell’s appointed Community Relations Commissioner (1973–1976) and played a key role in the development of the Atlanta gay press through his editorship and ownership of The Barb (1974–1977). Adapted from the book A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution (New York: W.W. Norton, 2021). Reprinted with the permission of W.W. Norton.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

Introduction: Series Editor's Note

Martin Padgett's A Night at the Sweet Gum Head explores a cast of historical actors who shaped modern LGBTQ+ politics and culture in 1970s Atlanta, Georgia. This cast includes Frank Powell (who owned "more than a dozen gay bars" including the Sweet Gum Head from the late 1960s until his death in 1996), John Greenwell a.k.a. "drag superstar" Rachel Wells, and the activist and trailblazer Bill Smith, who is featured in Padgett's excerpt published here with "Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces." Padgett, too, is central to the narrative he crafts. He writes: "As for me, [the book is] something of a memoir. In many ways, John and Bill and I have lived the same life, in our search for the place we call home, in search of our true selves. . .This isn't my story of Atlanta. It's mine too. It belongs to us" (xiv, emphasis added).

What follows is excerpted from Padgett's "Preface" and a glimpse into Bill Smith's participation in the first Atlanta Pride march on June 27, 1971. This is one of the many entries in Padgett's book that traces the evolution of Bill Smith in 1970s Atlanta until his death in 1980. This exploration of Smith is a brief snapshot of the many nights at the Sweet Gum Head in Padgett's book: pick up your copy to read more about Smith, John Greenwell/Rachel Wells, and the development of LGBTQ+ life across 1970s Atlanta.

From Preface

Today, American lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people, and queers can get married. We can find short-term special friends or life partners on our smartphones. We can venture proudly and safely into the straight world outside the confines of bars and clubs once designated specifically as "gay spaces."

Fifty years ago, none of those things was true. Queer people were shamed and muted, jailed, exiled, and put in danger. Often they were left no choice but to leave home, and to run away to cities where they might be accepted, or at least tolerated.

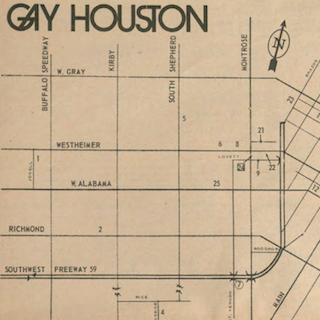

Even in those cities, gay bars were dangerous and illicit places—but they were also the birthplace of the emerging gay rights movement. Queer communities formed, and they demanded equality. It was a time of heady optimism. Many believed anything was possible, even progress. The movement had its most visible roots in New York and San Francisco, but after it flared in the riots at the seedy Stonewall Inn tavern in 1969, it spread quickly to cities such as Atlanta, a relatively progressive oasis surrounded by ultraconservative mores.

In the 1970s, Atlanta's cruisy, electric core was the Sweet Gum Head nightclub, where an intoxicating blend of drag, drugs, disco, and revolution had a pivotal role in uniting Atlanta's gay civil-rights movement—and in turning Stonewall's rebellion into art. The Sweet Gum Head is where Atlanta earned its reputation for top-flight female impersonation. It's where Atlanta's drag came out of the closet.

Before RuPaul Charles, there was John Greenwell, who ran away from Alabama to Atlanta and found a new home at the Sweet Gum Head. John became Rachel Wells—and Rachel became a drag superstar. Along the way, John put the two halves of his life back together.

John left the marches and protests to activists like Bill Smith. A son of devout Baptists, Bill took a seat as a city commissioner, then took over the most influential gay newspaper in the South, The Barb. When his addictions and predilections were revealed, he lost everything.

Then it all died. In the same summer of 1981 when the Sweet Gum Head closed, the New York Times reported on a "rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals."

Bill Smith, Georgia State Capitol, Summer 1971

The television camera stared at Bill as he strode down the sidewalk. He wore his usual explosion of red-brown hair and goatee, squared-off spectacles, and a white button-down shirt. He clutched protest signs and slung a white purse over his left shoulder as he led more than a hundred protestors from downtown Atlanta to Piedmont Park on June 27, 1971.

He fronted an army of lovers in warpaint and war robes, a Seussian spectacle with signs and bongos and buttons. One marcher hummed through a blue-and-orange kazoo, tootling it beneath a shock of golden hair and gold-rimmed glasses. Another wore a bowl cut, black-rimmed frames, and a mock turtleneck. He sniffed a red carnation and licked his lips luridly.

They marched two by two, animals on an ark, forced by the police onto the sidewalk and to stop for traffic lights and pedestrians. They had asked the ACLU for help with a permit to march, but were told they were not a minority.

People in cars took leaflets and stared as the group tambourined their way to the park and called to motel balconies: "Join us!"

"This is just like the early anti-war marches," one straight-identified protester marveled, "the way passers-by stare at us."

Bill's eyes angled down, dark and serious, as he spoke into the television camera.

"As people find out that you are a homosexual, there's a good chance that you may lose your job," he said with a bit of a lilt in his voice. His bony shoulders shifted while he proceeded with his lecture, part plea, part civic lesson. He told dinner-hour Atlanta how being gay affected every aspect of his life, even outside the bedroom.

"The state will not hire homosexuals," he said. "The schools will not hire homosexuals. The federal government will not hire homosexuals. They consider us a security risk."1Bill Smith, interview by WSB-TV, "Gay Rights Protestors March in Atlanta," The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at UGA Libraries, Athens, Georgia, June 27, 1971.

He parsed his words carefully. Atlanta was not San Francisco. He warned Northern friends, half in jest, not to mention General Sherman's name unless they were prepared to be bashed. He worried the Klan would shoot at protestors from the rooftops of nearby buildings. He spoke past that fear, directly to the more than 100,000 gay men and women who lived in Atlanta but had not come to demonstrate, who could lose everything—jobs, churches, family—if they joined the first Gay Pride march in Atlanta history.

Bill had worried that Atlanta still was not ready to mount a successful protest. He knew he could count on seven friends to show up, but on the day of the march more than a hundred had shown up, and some of Bill's closeted friends told him that they had driven around where the marchers had gathered, in silent support.

"Five or 10 years ago nobody would have suspected this," Bill said.2United Press International, "50 in Atlanta Mark Gay Liberation Day," Atlanta Journal Constitution. June 28, 1971. 9A. "It is a new beginning for the gay community."

At Piedmont Park, the march re-formed as a rally replete with guerrilla theatre. In the first skit, soldiers shot at Vietnamese peasants under orders, and had their medals ripped off when they questioned why. Next, police threw people to the ground and hurled epithets—"Queer!" "Lezzy!" "Fag!" In the final act, a panel of experts interrogated a straight couple on the Slick Cavett Show: "How long have you been this way?" Atlanta's first Pride ended with promises for bigger, better, and more.3cyclops, "Celebration . . . Very Gay," Great Speckled Bird, July 5, 1971, 2.

Bill went home to see himself on the evening news. He reported for work the next day as usual at the Board of Education's accounting room. His colleagues stared straight ahead and would not speak to him. Bill laughed and got down to work.4Dave Hayward in discussion with author, November 11, 2017.

About the Author

Martin Padgett has an MFA from the University of Georgia's Grady College of Journalism and is working on a new book about Michael Hardwick and the 1986 Supreme Court sexual-privacy decision bearing his name.

Cover Image Attribution:

Participants in the Atlanta Pride parade, Atlanta, Georgia, June 27, 1977. Atlanta-Journal Constitution courtesy of Georgia State University Library.Recommended Resources

Text

Bérubé, Allan. My Desire for History: Essays in Gay, Community, and Labor History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Bronski, Michael. A Queer History of the United States. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2011.

Chenault, Wesley and Stacy Braukman. Gay and Lesbian Atlanta. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Fleischmann, Arnold and Jason Hardman. "Hitting Below the Bible Belt: The Development of the Gay Rights Movement in Atlanta." Journal of Urban Affairs 26, no. 4 (2004): 407–426.

Howard, John, ed. Carryin' On in the Lesbian and Gay South. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South: An Oral History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Web

The Barb. Atlanta History Center (Atlanta, Georgia). Accessed December 7, 2021. https://album.atlantahistorycenter.com/digital/collection/p17222coll17.

Farmer, Jim. "A History of Atlanta Drag Bars." Georgia Voice, August 27, 2020. https://thegavoice.com/community/a-history-of-atlanta-drag-bars/.

Out In The Archives. Georgia State University Library (Atlanta, Georgia). Accessed December 7, 2021. https://exhibits.library.gsu.edu/current/exhibits/show/out-in-the-archives.

Padgett, Martin. "Underneath the Sweet Gum Tree." Oxford American, August 10, 2020. https://www.oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-109-110-summer-fall-2020/underneath-the-sweet-gum-tree.

———. "Before TV, Leslie Jordan was Miss Baby Wipes." Bitter Southerner, October 8, 2020. https://bittersoutherner.com/southern-perspective/2020/beforetv-leslie-jordan-was-miss-baby-wipes.

Waters, Michael. "The Stonewall of the South that History Forgot." Smithsonian Magazine, June 25, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/stonewall-south-history-forgot-180972484/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Bill Smith, interview by WSB-TV, "Gay Rights Protestors March in Atlanta," The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at UGA Libraries, Athens, Georgia, June 27, 1971. |

|---|---|

| 2. | United Press International, "50 in Atlanta Mark Gay Liberation Day," Atlanta Journal Constitution. June 28, 1971. 9A. |

| 3. | cyclops, "Celebration . . . Very Gay," Great Speckled Bird, July 5, 1971, 2. |

| 4. | Dave Hayward in discussion with author, November 11, 2017. |