Overview

In this peer-reviewed short narrated video and companion essay, Anthony Martin, Steve Bransford, Michael Page, Anandi Salinas, and Shannon O’Daniel explore the ecosystems of Sapelo Island, a barrier island on the Georgia coast. The authors’ ground and aerial drone-video footage illustrates a past that may forecast the future under climate change.

This piece joins two other Georgia barrier island flyover videos: St. Catherines Island Flyover and Ossabaw Island Flyover.

Video and Essay

A barrier island on the Georgia coast, Sapelo has an unusually long and varied blend of natural and human history. The western half of the island is composed primarily of Pleistocene sediments deposited along a shoreline 40–50,000 years ago. Much of its eastern half is more recently formed and dynamically shifting. Modern ecosystems include extensive salt marshes with tidal creeks, beaches, maritime forests, back-dune meadows, grasslands, and a few human-made freshwater ponds. Erosion occasionally reveals sediments from older environments, such as hundreds-year-old relict marshes exposed along Cabretta Beach on Sapelo's northeastern edge.

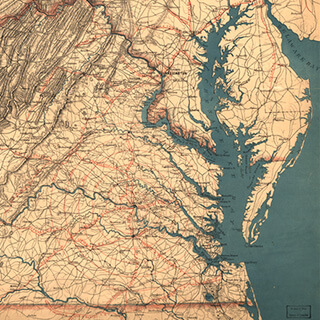

Sapelo Island in the Sea Islands Watershed. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.5.

The Sapelo climate is temperate to subtropical; temperatures range from an average high of 90°F (32° C) in summer to 50°F (10° C) in winter. Freezing is rare. Rainfall is about 50 inches (127 centimeters) a year, with the majority of precipitation during the May–September hurricane season. Despite the impact of Hurricane Matthew on October 8, 2016, hurricanes rarely affect the Georgia coast. The worst was in 1898, and directly impacted Sapelo and its companion, Blackbeard Island, to the northeast. Until the 1898 hurricane hit, Blackbeard hosted a US Marine Hospital yellow-fever quarantine station, which was damaged heavily by the storm; it reopened, only to close in 1909 with the development of yellow-fever vaccines.

A prominent and well-preserved Native American (Guale) shellring on the northwestern corner of the island gives evidence that humans have experienced Sapelo for at least 4,500 years. The arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century resulted in the naming of "Sapelo," an Anglicized corruption of "Zapala" from Spanish and likely a corruption of the original Guale name for the island. French and English colonization of Sapelo in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries heavily modified the local ecosystems.

Following the American Revolution, alteration of the local environment continued throughout the early to mid-nineteenth century. Plantation agriculture depended on slave labor of people with varied languages and origins in west Africa, resulting in an enforced cultural mélange. Descendants of those enslaved people, and the only Gullah-Geechee population on any Georgia barrier island, reside today in the Hog Hammock community. Although shrinking in size, Hog Hammock retains a distinctive culture and features a revival of traditional knowledge, including handicrafts such as sweetgrass basket weaving, cultivation of unique agricultural species (e.g., Sapelo red peas), and Gullah-Geechee storytelling.

Top, the UGAMI complex on Sapelo Island, Georgia, 2015. Bottom, lighthouse on Sapelo Island, Georgia, 2015. Screenshots courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Perhaps the most scientifically significant legacy of Sapelo is its birthing of modern ecology, much of which was done at the University of Georgia (Athens) Marine Institute, or the UGAMI, founded in 1953. The UGAMI owes its existence to ecologist Eugene Odum (1913–2002) and tobacco heir/businessman R.J. Reynolds, Jr. (1906–1964). Reynolds bought most of the island in 1934, but Odum persuaded him to donate land and buildings to start the UGAMI in 1953. The Institute, located next to its study sites, has conducted world-renowned research on salt-marsh ecology and other aspects of natural communities on and around the island.

Reynolds' widow, Annemarie Reynolds, sold much of the island to the state, which the Georgia Department of Natural Resources now manages. The western edge of Sapelo is part of NOAA's National Estuarine Research Reserve system, termed the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve. The UGAMI still serves as a thriving center for ecological research and hosts academic field trips in natural science education.

In September, November, and December 2015, we visited Sapelo Island to gather ground and aerial drone-video footage that would visually summarize its ecosystems. This footage also shows signs of human activity, such as the UGAMI complex, paved roads, a freshwater pond created by excavation, and the present-day lighthouse, still used for guiding maritime traffic in Doboy Sound.

Internal Waterway, Sapelo Island, Georgia, 2015. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.

Our first trip in September 2015 also coincided with "king tides," spring tides accentuated by a relatively stronger gravitational pull associated with a "super moon." This situation caused unusually high tides to flood marshes, roads, and other low-lying places on Sapelo, a phenomenon repeated there and along the rest of the Georgia coast in late October 2015. Tidal ranges on the Georgia coast are already greater than those of most barrier island systems, typically varying from 2.5–3 meters (8.2–9.8 feet). Any addition to this already-voluminous water exchange imparts dramatic effects. Some of the drone footage showing the extent of the flooding serves as a harbinger of predicted sea-level rise on the east coast associated with climate change. We also included two snippets of time-lapse sequences of intertidal areas—Cabretta Beach, on the northeastern corner of the island, and a salt marsh in the south end—to further convey the effects of tides on island margins and interiors.

This Sapelo video encapsulates a history that forecasts the future under climate change. Among its subjects are: abrupt transitions in coastal ecosystem, from beach to back-dune meadows to maritime forests; beaches where sand is being actively eroded or deposited by longshore drift; a tree "boneyard" with dead trees on a beach signaling the former presence of a maritime forest; an artificial freshwater pond adjacent to maritime forest but with salt marshes in the background; dendritic drainage patterns of marshes at low tide, and much more. Despite its short 3:45-minute length, this video's content, combined with its brief narrated descriptions, can inspire an hour or more of classroom discussion of natural and human systems on this remarkable Georgia barrier island.

About the Authors

Anthony (Tony) Martin is a professor of practice in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Emory University. His publications include Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013). Steve Bransford is an educational analyst for video with University Technology Services at Emory. He launched his own production company, Terminus Films, in 2001. Anandi Salinas is a PhD candidate in religion at Emory and a training specialist with the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship. Michael Page is lecturer in geospatial sciences and technology at Emory. Shannon O'Daniel is an educational analyst with Emory's Library and Information Technology Services.

Cover Image Attribution:

Aerial view of Sapelo Island. Sapelo Island, Georgia, 2015. Screenshot courtesy of Southern Spaces.Recommended Resources

Text

Bailey, Cornelia, and Christina Bledsoe. God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man: A Saltwater Geechee Talks About Life on Sapelo Island, Georgia. New York: Anchor Press, 2001.

Chalmers, Alice G. The Ecology of the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve. Sapelo Island, GA: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coastal Resource Management, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 1997.

Craige, Betty Jean. Eugene Odum: Ecosystem Ecologist and Environmentalist. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Fraser, Walter J., Jr. Low Country Hurricanes: Three Centuries of Storms at Sea and Ashore. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Gregory, Murray R., Anthony J. Martin, and Kathleen A. Campbell. "Compound Trace Fossils Formed by Plant and Animal Interactions: Quaternary of Northern New Zealand and Sapelo Island, Georgia (USA)." Fossils and Strata 51 (2004): 88–105.

Jeffries, Richard W., and Christopher R. Moore. "Recent Investigations of Mission Period Activity on Sapelo Island, Georgia." Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective 5, no. 1 (2010).

Johnson, Michele Nicole. Images of America: Sapelo Island's Hog Hammock. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Martin, Anthony J. Life Traces of the Georgia Coast: Revealing the Unseen Lives of Plants and Animals. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Sullivan, Buddy, "Sapelo Island Settlement and Land Ownership: A Historical Overview, 1865–1970." Occasional Papers of the Sapelo Island NERR 3 (2014): 1–24.

Thompson, Victor D., Matthew D. Reynolds, Bryan Haley, Richard Jefferies, Jay K. Johnson, and Laura Humphries. "The Sapelo Shell Ring Complex: Shallow Geophysics on a Georgia Sea Island." Southeastern Archaeology 23 (2004): 192–201.

Worth, John E. The Struggle for the Georgia Coast: An Eighteenth-Century Spanish Retrospective on Guale and Mocama. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1995; distributed by University of Georgia Press.

Web

Crook, Ray. Gullah-Geechee Archaeology: The Living Space of Enslaved Geechee on Sapelo Island. The African Diaspora Archaeology Network. March 2008. http://www.diaspora.illinois.edu/news0308/news0308-1.pdf.

"The Islands." In An Ecological Survey of the Coastal Region of Georgia. U.S. National Park Service Scientific Monograph No. 3. Last updated April 2005. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/science/3/chap3.htm.

Martin, Anthony J. "Fossils in Progress." Life Traces of the Georgia Coast. Blog. November 22, 2011. http://www.georgialifetraces.com/2011/11/22/fossils-in-progress.

Martin, Anthony J. "Rooted in Time." Life Traces of the Georgia Coast. Blog. July 30, 2015. http://www.georgialifetraces.com/2015/07/30/rooted-in-time.

"Sapelo Island Cultural and Revitalization Society (SICARS): Preserving Geechee/Gullah Culture, Land and Community on Sapelo Island, Georgia." Sapelo Island Cultural and Revitalization Society, Inc. Accessed July 12, 2017. http://www.sapeloislandga.org.