Overview

In this essay, Ellen Griffith Spears situates Southern Spaces' series "Landscapes and Ecologies of the US South" in the field of eco-cultural history, describing how the pieces in the series challenge critical memory, both temporally and in space.

"Landscapes and Ecologies of the US South: Essays in Eco-Cultural History" serves as an introduction to the 2011 Southern Spaces series "Landscapes and Ecologies of the US South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary publications about natural and built environments.

Essay

|

| Nancy Marshall, Altamaha River, Georgia, 2010. From "James Holland, Riverkeeper: Environmental Protection along the Altamaha." |

Chiding conventional historians for their neglect of nature has a long tradition among environmental historians.1Adam Rome, "What Really Matters in History?: Environmental Perspectives on Modern America, "Environmental History 7, no. 2 (2002): 303–318. Scholars have similarly lamented environmental historians' lack of attention to southern locales, with most of their emphasis on New England and the US West. Otis L. Graham in "Again the Backward Region?" (2000), Mart Stewart, in "Southern Environmental History" (2002), and Christopher Morris in "A More Southern Environmental History" (2009) have each tackled the subject of inattention to southern places in environmental history.2Otis L. Graham, "Again the Backward Region?: Environmental History in and of the American South," Southern Cultures (Summer 2000): 50–72; Mart A. Stewart, "Southern Environmental History," in John B. Boles, ed., A Companion to the American South (Maiden, MA: 2002), 409–423; and Christopher Morris, "A More Southern Environmental History," The Journal of Southern History 75, no. 3 (August 2009): 581–598.

However, as Stewart and others have pointed out, the record of attentiveness to landscapes and ecologies in Southern Studies and environmental history is more complex. Historian Barbara J. Fields argued at a conference of southern regionalist historians in the late 1990s that "[t]he natural environment figured so importantly in earlier historians' understanding of causation in human affairs" that it was taken for granted. Fields was concurring with environmental historian Jack Temple Kirby in Rural Worlds Lost that scholars in this emergent historical field were actually, as Fields put it, "rejoining a temporarily neglected line of inquiry rather than initiating a new one without respectable precedent."3Barbara J. Fields, "Commentary on Jack Temple Kirby's paper 'Bioregionalism: Landscape and culture in the South Atlantic,'" in The New Regionalism: Essays and Commentaries, ed. Robert L. Dorman and Charles Reagan Wilson (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 38; Jack Temple Kirby, Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920–1960 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987).

Perhaps that earlier focus on natural history was especially great because the impact of climate and disease was so wrapped up with the very definition of the South as a distinct section of the US4James O. Breeden, "Disease as a Factor in Southern Distinctiveness," in Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South,1st ed., ed. Todd Lee Savitt and James Harvey Young (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 1–13, 11. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century southern historians engaged with environment all along, though they often did so in deterministic ways, constrained by race, gender, and class as well as geography. The problem was not that nature was not in the picture, but rather in how human relationships with the rest of nature changed and were portrayed.

|

| Duval News Company, Old Slave Market, St. Augustine, Fla., Oldest City in the United States, c. 1915, recto. Collection of the Author. From "St. Augustine's 'Slave Market': A Visual History." |

The field of southern environmental history is moving beyond this critique, undergoing a rich elaboration. Even the descriptors of the field are changing. The essays in the Southern Spaces series, "Landscapes and Ecologies in the US South," form part of a growing branch of this genealogy, one that critical literary scholar Rob Nixon, author of Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (2011) has termed "eco-cultural history."5Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011), 85. These six multimedia essays—chosen from competitive submissions—contribute to the scholarship in significant ways that represent and amplify changes afoot in eco-cultural history. These vibrant essays move across time and space, some engaging in fresh ways with traditional environmental subjects of bioregion and agriculture, others exploring the interconnections with places beyond the southern states, attending more closely to labor, and highlighting the role of militarism in ecological devastation.

Three of the essays mark the extent to which the ecologies within the US South are situated across the Atlantic World: Holly Markovitz Goldstein's "St. Augustine's Slave Market: A Visual History"; John Howard's "Palomares Bajo"; and Charles D. Thompson, Jr.'s "Visions for Sustainable Agriculture in Cuba and the United States." Each in its own time and manner show the embeddedness of the US South in the global flows of commerce. A professor at Savannah College of Art and Design, Goldstein's look back at how St. Augustine's slave market is memorialized notes the collective and willful forgetting by Americans about slavery. Taking off from the installation of the first public civil rights monument at the market "honoring the struggle for equality on this site of white terror," Goldstein points to the slave market's role in the twentieth century as an "all-purpose protest site." Efforts by "heritage tourism" advocates to elide the site's true significance miss a significant opportunity to illuminate history.

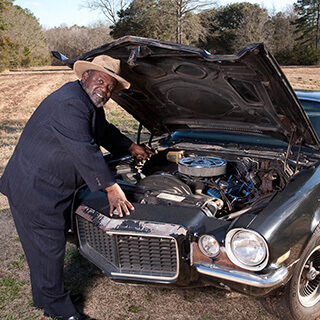

|

| Charles D. Thompson, Jr., Pedro Rodriguez Pérez, a Cuban farmer, Trinidad, Cuba, December 2010. From "Visions for Sustainable Agriculture in Cuba and the United States: Changing Minds and Models through Exchange." |

In "Palomares Bajo," John Howard, professor of American Studies at King's College in London, calls our attention to far more recent events in the Atlantic World, when in 1966, at the height of the Cold War, a US B-52 collided with its refueling plane and dropped two nuclear bombs over the Spanish Andalucían coast near the town of Palomares. The Soviet Union-bound test run had taken off from Goldsboro, North Carolina, and the limited cleanup operation buried contaminated soil at the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina. Like Goldstein, Howard aims to "counteract cultural amnesia" about the events, termed "the worst nuclear weapons disaster" in history.

Moving to the present day, but also exploring remnants from the Cold War, Charles D. Thompson of the Duke University Center for Documentary Studies, along with Alexander Stephens of the Marian Cheek Jackson Center examine the prospects for sustainable agriculture offered by exchanges now taking place between agronomists in Cuba and the United States Thompson critically assesses the portrayal of contemporary Cuba as "the accidental Eden"—arguing that policies that protected Cuba's coastal landscapes from high-rise beach development were hardly accidental, but planned, and the designation as Eden, as is frequently deployed in depictions of US environmental history, is overblown. Thompson cites figures showing food insecurity (households facing hunger during some part of the year) on the rise in the United States and compares the figures with rates in Cuba. He offers a sympathetic portrait of the Cuban countryside and the possibilities for greater agricultural collaboration once the United States lifts its embargo.

|

| African American laborer chipping trees, outside Lockhart, Alabama. Forest History Society archive. From "Inside the Jackson Tract: The Battle Over Peonage Labor Camps in Southern Alabama, 1906." |

Labor and environmental history form the central pillars of University of Texas at Austin doctoral candidate Aaron Reynolds' work, as he reconsiders the early twentieth century in "Inside the Jackson Tract: The Battle Over Peonage Labor Camps in Southern Alabama, 1906." Peonage in Alabama has been strikingly revealed by Douglas Blackmon in Slavery By Another Name (2008, released in 2012 as a compelling PBS film).6Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, 1st ed. (New York: Doubleday, 2008); Sam Pollard, "Slavery by Another Name," PBS, 2012, 90 min. Reynolds complements Blackmon's account by documenting the conflict between the Progressive Era conservationism and brutal working conditions faced by African American and immigrant contract laborers in south Alabama's pine forests. In so doing, he highlights the resistance mounted by the workers themselves and the posture assumed by Booker T. Washington in the federal investigation of peonage conditions.

The most widely published of the contributors to the Landscapes and Ecologies series, author Janisse Ray, shares an excerpt from her Drifting into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River. In "James Holland, Riverkeeper: Environmental Protection along the Altamaha," nature writer Ray and photographer Nancy Marshall acknowledge the singular dedication to protecting the landscape by a cadre of riverkeepers across the southern United States In recounting the work of Holland and Deborah Sheppard, executive director of the Altamaha Riverkeeper group, with her customary lyricism, Ray honors unsung activists who have labored mightily for incremental and significant improvements in water quality and river health.

In an ode to bioregionalism, the study of landscapes defined not by political boundaries, but by their ecological terrain, Wofford College poet John Lane writes of his efforts to build a writers' group in Spartanburg, South Carolina, around "a language grounded in the metaphors of ecology, biology, and natural processes." Under the influence of poets such as Gary Snyder, the result, as Lane describes in "Still under the Influence: The Bioregional Origins of the Hub City Writers Project," is a literary community built around ecological ideas. Lane acknowledges that the scientific concepts in ecology have shifted in the more than thirty years since he began this work, but the literary endeavor he developed has enriched the cultural landscape of this conservative former cotton mill town.

|  |

| John Howard, Plásticos, Near Bomb Site #2, Palomares, Spain, April 2011. From "Palomares Bajo." | John Lane, Kayakers on the shore of Lawson's Fork, Spartanburg, South Carolina, 2007. From "Still under the Influence: The Bioregional Origins of the Hub City Writers Project." |

Online multimedia series such as this collection of essays—combining interactive photos, graphics, maps, video, and texts—speak to the study of eco-cultural history in ways traditional publications cannot. Combining old and new photos, postcards, and text in near equal measure, Goldstein traces the evolution of the racial imaginary surrounding St. Augustine's slave market. Howard's photographs of Palomares explicitly invoke prominent American photographer Richard Misrach's Nevada test site images. Thompson's vivid photos and video of the Cuban countryside offer a glimpse into this part of the hemisphere few Americans have ever visited. These multimedia essays are suggestive of the rich landscapes to be explored in southern eco-cultural history. Each of these writers has challenged critical memory, both temporally and in space. Southern Spaces' forthcoming series, on "Spatial Justice," promises to expand these horizons.

About the Author

Ellen Griffith Spears is assistant professor in the interdisciplinary New College and the Department of American Studies at the University of Alabama. She served as a guest editor for the "Landscapes and Ecologies in the US South" series.

Recommended Resources

Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, 1st ed. New York: Doubleday, 2008.

Kirby, Jack Temple. Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Savitt, Todd Lee and James Harvey Young. Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, 1st ed. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Adam Rome, "What Really Matters in History?: Environmental Perspectives on Modern America, "Environmental History 7, no. 2 (2002): 303–318. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Otis L. Graham, "Again the Backward Region?: Environmental History in and of the American South," Southern Cultures (Summer 2000): 50–72; Mart A. Stewart, "Southern Environmental History," in John B. Boles, ed., A Companion to the American South (Maiden, MA: 2002), 409–423; and Christopher Morris, "A More Southern Environmental History," The Journal of Southern History 75, no. 3 (August 2009): 581–598. |

| 3. | Barbara J. Fields, "Commentary on Jack Temple Kirby's paper 'Bioregionalism: Landscape and culture in the South Atlantic,'" in The New Regionalism: Essays and Commentaries, ed. Robert L. Dorman and Charles Reagan Wilson (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 38; Jack Temple Kirby, Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920–1960 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987). |

| 4. | James O. Breeden, "Disease as a Factor in Southern Distinctiveness," in Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South,1st ed., ed. Todd Lee Savitt and James Harvey Young (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 1–13, 11. |

| 5. | Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011), 85. |

| 6. | Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, 1st ed. (New York: Doubleday, 2008); Sam Pollard, "Slavery by Another Name," PBS, 2012, 90 min. |