Overview

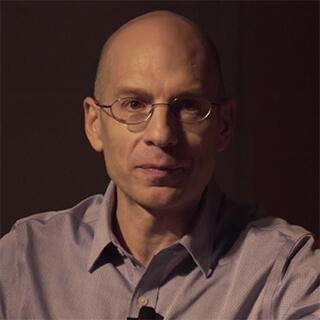

Malinda Maynor Lowery, writer and producer of Lumbeeland, discusses the making of this short fiction film set in modern-day Robeson County, North Carolina. Lumbeeland grapples with the intergenerational experiences of a family involved in drug trafficking and the effects of substance misuse. Lowery reflects upon the challenges of script writing, the importance of collaboration, the extensive participation of Native people in the project's creation and production, and the film's public reception.

Click here to stream Lumbeeland for free at First Nations Experience.

Southern Spaces: Malinda, tell us about your film Lumbeeland. Why and how did you come to work on this project?

Malinda Maynor Lowery: Lumbeeland is a twenty-nine minute short narrative, live-action film set in the Lumbee Indian community of Robeson County, North Carolina. It features a young Native man who is intent on taking over his grandfather's marijuana trafficking business. He encounters unexpected challenges and finds himself in over his head. He has to face up to what he loses in the process. For me, that narrative was a way of investigating deeper questions around the consequences of actions that we take. “You reap what you sow” was the original concept. What are the intergenerational ways in which we reap what we sow? How are we responsible? Why do we feel guilty for things we didn't do? How are we responsible for things that our ancestors did in good and bad ways, or accountable for choices that we didn't make?

I’m a historian but I’m also a member of the community that I write about. The specifics around the story of Lumbeeland came from experiences of family members who have been involved in drug trafficking and substance misuse. It’s something that we live with, but are not allowed to talk about. It causes shame and it causes anger. You see the devastating consequences of these substances, not just for the individual’s well-being, but also for how substances become commodities in a global market. Individual users are often seen as driving the drug trade, but they're not, or at least not by themselves — any more than I'm driving the bottled water trade.

We have to talk about that problematic commodity and the many people who profit from its trade. What I've never heard talked about was that my relatives who are misusing substances are part of a larger system that they don't have control over. That's not to excuse their behavior or say that there should not be any consequences for the choices that they make. But we should be able to talk about the system that creates these negative choices. And we need to be able to talk about the impact of those choices on communities of people. Substance use is something that affects families in addition to users.

In my family, we were not able to openly address the way we felt angry or powerless or ashamed. To me, this maps directly on to the lifelong engagement I have with history. I'm constantly writing from the standpoint of being responsible for choices that I didn't make. Living with history means we are all responsible, in some way, for choices we had no hand in. And I feel that way about people when we talk about substance use. We need to be thinking about it in terms of who does it impact beyond law enforcement, beyond users, beyond drug traffickers.

It also impacts people who are members of families who may be experiencing incarceration as a result of these activities, and who are experiencing health problems. The story I decided to tell in Lumbeeland engages these themes. It was a way to deal with my own sense of shame and anger about how a drug economy has affected my family and my community.

Film is a good way to elevate one's sense of empathy — you see somebody who's different from you in a new light because that experience is in the context of a story.

This was about seeing myself and the people who are most like me in a different light and enabling Lumbee people to see themselves on the screen. I know all of the people in Lumbeeland in one way, shape, or form. My hope is that the film will help people feel more connected to one another and get a greater sense of compassion for our own struggles. The experience of drug trafficking and drug use is in every Lumbee family. I hope Lumbeeland will not only allow us to be more empathetic, but it will also give us a sense that this is a problem that comes from somewhere and has a history.

I also know from doing history that if we can talk about how this history came to be, we can also talk about how to undo it or how to do it differently. But right now we don't want to talk about this topic. We're afraid, ashamed, and angry, and, I might be rushing ahead, but it's a deeply troubling phenomenon as a Native American person in this country to know who took what you have. Who took our wealth. Who took our property. Who took our language. Who took our culture.

We still have a lot. But what we have had is no longer in our possession. In the case of the Lumbee community, we didn't experience the geographic displacement that so many other tribes did in the Southeast, so today we live next to the people whose families took it. We know who took it but we can't hold them accountable because the system of justice that was instituted without our permission, that we now belong to, but didn't consent to, doesn't allow us to hold those people accountable. That generates anger and shame that drives people to dysfunctional solutions. That’s the big background to Lumbeeland, although it’s not explicitly addressed. I hope to be able to talk about more in other related stories. I think of Lumbeeland as kind of like the Marvel Universe. Not because it's cartoon heroes, it's a real place, but because you can tell many, many kinds of stories with many kinds of people and experiences.

Southern Spaces: Lumbeeland immediately immerses viewers into a family crisis. It's intense and emotionally powerful. The film also displays a great ear for vernacular speech. How did you go about the writing?

Lowery: I'm not a trained screenwriter. I'm a trained historian, nonfiction writer. It was actually much harder for me to write than I imagined when I started. That's partly because of the nature of the topic, but also because historians don't specialize in creating fictional characters out of non-fictional situations. We tend to sit in archives and pull from there what’s relevant.

Historians explore nonfiction by looking at all angles. What I learned was in writing a screenplay, you have to have characters. And those characters have to do things, not necessarily express ideas. Obviously, characters will have ideas and will talk about them. But if you think about of the history of drama in Western European society, from the Greeks to Shakespeare, they are about action. Their characters announce what they are doing.

There are Indigenous forms of drama, but Lumbeeland was very much written in a Greek and British style of drama, like most contemporary film and television. In film, we expect to see what the characters do, not so much hear about it. I had to get familiar with the basic principles of dramatic writing and structure. Who are these people and what do they want? Why do they want this? That was surprisingly hard to come up with because as a historian I do think about people and why they do what they do, but I explain it less by their individual backstories and more by the structures and societies they live in.

I drafted an essay in 2013 that wound up in the Oxford American in 2020. The original title of that essay was “Lumbee Land” and was a kind of love story. But quickly, I began to think: what am I trying to say? What do I really care about? And, especially through writing the sixth chapter of my second book, which is about the drug war in the 1980s, what would I like to say about that? I had to think about character, nature, backstory, and action in a different way. Substance use and misuse is intergenerational trauma that lives unacknowledged in our bodies if we're not actively trying to wrestle with it. Because of action, theater and film are completely embodied art forms as much as dance or music.

The characters in Lumbeeland began to emerge through people that I have known. When I started to have a breakthrough, I imagined the family in the film. I thought hard about what situation would create dramatic interest. This idea about a contest between father and daughter, grandfather and granddaughter or grandson, with a more vulnerable individual caught up in it. It's meant to convey a multi-generational experience as a Lumbee person, as well as how that relates to colonialism and trauma, and how it affects our families. The other reason to make a film was many of the people who shared their experiences with me for the purposes of my book, never wanted to go on record and never wanted to be named.

Because I have a background in documentary filmmaking, it might have been more logical to ask people’s permission to film their lives and film them talking about their lives. But people who are enmeshed in this world do not want a camera in their home, or anywhere near. The necessity to fictionalize came up early on as I was thinking about what do I do with these intense feelings I have about how this problem is affecting our community. It made sense to find a way to put my feelings on the screen through the experiences of these different characters.

Then you've got a thousand decisions to make: What's the setting? What time period? How to make tangible in these characters the theme of “you reap what you sow.” How to unfold the scenes, the rhythm of the shots, the editing, and the music.

Playwrights talk about the thought of the play, the idea of the play. I also worked with Joan Scheckel, a screenwriting, acting, and directing coach who holds workshops and seminars in Los Angeles. She talks about the thought as a nugget, something you can imagine holding in your hand.

I like collaboration and have done so much of it over the course of my career. Film is an inherently collaborative form. I didn't direct Lumbeeland. I had a hard enough time writing it, and I knew I wanted to produce it. The director we worked with, Montana Cypress, is phenomenal. He's a Miccosukee person from the Southeast, an actor, writer, and director. He works with actors who aren’t formally trained a lot in his own films. He gets the nature of the community, the landscape, and the issues that we're dealing with.

The other key moment in bringing the final version to fruition was a set of table reads that we started. We shot the film in May and June of 2023. I had a version that was readable by Labor Day of 2022. We did the reading in Pembroke, our home community. I invited friends and actors who live there to participate. They would say things like, “Don't we want to see a chocolate cake? Or, “We need to see Dock (one of the characters) doing something that Lumbee farmers do — they will hang a snake in a tree to get it to rain.” (And that day, when we were shooting, it actually rained!)

There are culture bearers who have Lumbee knowledge. People I got to know when I was producing an outdoor drama who are invested in the storytelling and cultural production of our people.

Two table reads brought people together to provide suggestions about what they thought would represent our community accurately. They also brought criticisms. And I've gotten criticisms since showing Lumbeeland: Why is this the story that we're picking to be the first narrative film produced, written by, and starring Lumbee people? My answer is that it’s my story, so I have to tell it, and I have a track record of going to the thing that’s hardest for us to talk about. My first film, back in 1996, was about racism both within the Lumbee community and directed towards Lumbee people. And folks didn’t want to talk about that either at that point. But now it’s different.

Southern Spaces: Can you say more about writing the dialogue and your use of vernacular speech? The characters come across as believable.

Lowery: Yes. That's why the table reads are so crucial. And why it's important to have Lumbee individuals — they don't have to be actors — reading the script. They can contribute lines of dialog, add flourishes, dialect notes, grammar, and pronunciation that resonates. A lot of that is in the script at the point when we read it together, but it always gets better when you hear Lumbee people say the words.

What also helped bring the film to life were vivid and relevant cultural elements that have a direct bearing on what the characters are going through. That's church, gospel music, a birthday party, our food. It’s the way we adorn ourselves. The way we talk. The way we invoke the past. The way we tell stories as we go about our lives. The way children will challenge parents, respectfully — it's rarely “You sit down and shut up.” We spend time with and listen to our children. We want to know what they think. And children are expected to pass time with elders. We try to make that vivid and visible in the film. It’s not a standard story about drug dealers and whether or not we should admire what they do. At one one event I did last year, I described Lumbeeland as being about bad people who want good things.

One of the things I really feel that works in the film is the rhythm with which people speak. It's the way we talk to each other. The use of language came straight out of me being Lumbee and having Lumbee collaborators. We had thirty-four people on set, twenty-four of whom were Native American, and twenty-two of those were Lumbee. All of the film’s producers and creative leads were Native, which is still unusual. They had a direct infusion into how it played out.

Actors definitely did some ad libbing. If they weren’t catching the line as written, we’d say, "Okay, say what you think this character would say.”

The person who did the most ad libbing was Antoinette Locklear Hurtt, who played Connie. And she got a best supporting actor nomination at a film festival last year. She's a police detective in real life, so she's ready for anything. There are three people in the cast who had acted before. Dollar, the lead character played by Billy Oxendine, a Lumbee, is a formally-trained stage actor. He’s just finished his MFA from the Actor's Studio at Pace University in New York. The other two actors who have appeared on screen are self-taught: Harvey Godwin, who played the grandfather, Dock; and John Scott-Richardson, who played Cortez. Billy had never been on screen, but he was the only person on set who had professional training. Danielle, played by Bethany Harris; Connie, played by Antoinette; and Gage, played by Roger Dale Locklear, had never acted before. They auditioned and we had a very strong sense of what they would be like on screen. They required very little coaching. We wanted them to bring their cultural sensibility.

It was a wonderful lesson to me, never having made a fiction film. You have the words on a page, but it is nothing without the people who are embodying the action. And then the director has to decide: are we going to reshoot this scene or are we going to go with it? A lot of stopping and starting can be disruptive for people who are not actors. But our cast got into the flow of it thanks to cinematographer Erika Arlee, along with Montana, and first assistant director Kristi Ray. And our producer, August Poncé, and consulting producer, Kim Pevia.

Film directors often stop and start within scenes. They're looking for particular timing or for an actor to hit a mark or, a facial expression that they want to capture. They'll stop if they're not getting that right. Montana's approach was to start and roll through the whole scene and to do our best to capture it from start to finish. He was great at knowing when we could push and when he had to stop.

What Montana and Erika wanted to do, and what I felt was in the spirit of the story, was a documentary style. To try to be in it with the characters. But as a writer you always have things that you've seen in your mind. Lumbee families love The Godfather. I'm thinking about that as I'm writing the script. But I'm mostly thinking about father-son, father-daughter relationships as they materialize.

On set, I tried to say, “I wrote the story, but now I'm here to be helpful.” You choose actors that you think are going to work with what’s intended. The biggest priority for me was the way they talked. And they just did it. Montana knew how to bring it out of them.

There’s a scene at the beginning, when Dollar is sitting and playing a video game and his daughter comes in and gives this epic eyeroll. I worked with her a little bit on that because I was like ‘Bethany, you know, you can give shade like nobody else.” Because I know her. And she's like, “Yeah, but that's not how she would do it.” And I was like, “Okay, I get that that's not how you would do it. But the way that you would do it, we're not going to be able to capture on the screen. So just be over-the-top with the eye roll.” And she did it and grinned.

Southern Spaces: There are scenes in Lumbeeland that evoke a film of a few years ago, Winter’s Bone.

Lowery: Yeah. My God, yes. Winter’s Bone was in my mind.

Southern Spaces: For instance, evoking the meanness of the men in similar cultural situations of power.

Lowery: Patriarchs and bosses. It’s just chilling. They don't care about people, but they're going to make you think they care about you. That’s part of the cultural dimension that’s hard to capture and hard to present. Then you get criticized for showing your dirty laundry. But that was what had to be done. And the actor who played Dock, Harvey Godwin, struggled with that. He and I had several conversations. He's not that kind of person, but he knows people who are. And I know people who are.

We tend to assume such people are irredeemable, or maybe that their stories are not worth telling. So I wanted to tread that line. They're often sensationalized. Think about the worst characters, a Hannibal Lecter, who is meant to strike fear in the audience. This film wasn't intended to strike fear in order to exploit entertainment, but to create situations where this character could show different sides of himself. He can make a cake for his grandson and great granddaughter. He can tell her a story. He can tell her that he loves her. And all the while he's also doing sinister things.

In a dramatic narrative, characters want something and you have to put those wants into relationship with each other, but not always conflict. I didn't want to write a story that was exclusively conflict based. These characters with various wants are in conflict with each other because of the situation that they're in. Some of which they created, and some of which was created for them.

I needed to be honest; to think about people's good and bad sides. How they can want good things and not be able to get them. They can change, even if there's an overarching continuity in how their behavior impacts other people. For instance—and we're not giving anything away—but the scene at the end of Lumbeeland, where Dock is walking up the stairs and putting his head in his hands. That wasn't in the script, but the crew was like, “We need this.” And I was like, “Yeah, let's shoot it. Let’s see what happens.” In the original script, Dock has no remorse, but the crew felt strongly that we need to show him reflecting on what he's done or what he's put in motion.

I didn't feel like I could make something and tell the truth that didn't explore toxic masculinity — in Lumbeeland and in our society — the existence of patriarchy and the damage that it causes. That truth needs to be out there.

The intergenerational tension between Dock and Dollar is one core of the film. How do you write that tension? The first place my mind goes is Dock's backstory, that we're not privy to in this version of the film, but he is in quite a bit of debt to a Lumbee-run drug cartel that he is a member of. He's taking Connie's money, and he is working with his best friend, The Dog, to be able to begin to pay off his debts. He's not double-crossing Dollar just because he has the power to do so. He is manipulating his family members to protect himself. That's the kind of experience of being a member of a family that I wanted to tell through this story. What does it feel like from Dollar’s perspective to be manipulated in this way? But also what does it look like from Dock's perspective to do the manipulating?

We don't have a concrete sense in the short film of why Dock is doing this. But he's using the material at his disposal — his relationships with the people that are closest to him — to get what he wants. He didn't anticipate The Dog dying. So here's this character whose nature is generous and actually indulgent, but he's also impulsive, and his life experience has made him ruthless.

How does this person respond when his best friend dies of an overdose? He thinks he knows who's responsible. And so the Dock-Dollar tension. Dollar also has his own goals, but runs into a problem with Child Protective Services that distracts him from being able to implement whatever kind of hazy plan this very young person, 25-ish, is going to have. He's not very experienced. He's not understanding the consequences of his actions. He's gloating over the success of this plan but he's in denial about what is about to happen to him. Both Dollar and Dock have to run up against obstacles in the theme of you reap what you sow.

I'm making it sound like it's all very planned, but it’s frankly a struggle when you're drafting.

There's a lot of things that I watched along the way. Such as Winter's Bone. Oh, my God, it's chilling how this young woman is in charge of redeeming a father who was never there for her. But she has to do it. Not for his sake, but for her own and for her siblings. That certainly speaks to a layer of my life that I don't talk about very much, but which I wanted to explore in a certain time and place.

Southern Spaces: In Lumbeeland there is not much open space or room to breathe. There is a sense of being enclosed and entrapped.

Lowery: It's so interesting that you highlight that. It was not such an intentional choice. It came about mostly because of budget and what you have time and space to shoot with the people that you brought.

At first, we didn't shoot many exteriors. We shot the drone shot that we use at the end of the film on the very first night. We knew that that was going to be included. But all the other exteriors were shot in a couple of hours about two months after the main production ended. We knew we had to have some because the film is about a specific place, the Lumbee homelands of North Carolina. But we didn't have a budget to drive to place after place. And I think about the other films we've referenced, if it's Winter’s Bone or True Detective or The Godfather, they rely on exteriors to create those worlds.

Ultimately, however, that worked to our advantage in terms of the emotional power of the story. You never get out of these characters’ tight interiors. You are with their bodies and their interior physical spaces. That's partly why it's harder to find moments of hope in the film. Despite all that has been taken from us, we still have elements of our culture and remnants of our land. We have our speech. These are hopeful elements, but because of the very interior nature of the film, it's hard to see them. That wasn't so much a strategic storytelling choice, but something that came out of the situation that we were in. And we had a great situation in which to shoot the film. It was shot in people’s homes — very generous, caring, flexible people who believed in the project and just wanted to see it happen and opened their doors for us. I don’t know if you’ve ever had a film crew in your house for a week but it’s crazy.

Southern Spaces: Although it’s just thirty minutes long, Lumbeeland conveys very intense, unsettling emotions, How is it being received? How have you shown it and what are you planning?

Lowery: We're very happy that it's streaming on a platform called FNX — First Nations Experience. It's a public media platform headquartered in Southern California that streams Indigenous content, mostly US-based. There are platforms that do this in other countries such as New Zealand and Australia. The FNX streaming app launched on May 1, 2025, and we were one of the films they premiered. We've been on the film festival circuit for about a year and won several awards including the Best Live Action Short from Red Nation International Film Festival. But I think the awards I'm proudest of are North Carolina-based, one from the Longleaf Film Festival which is in Raleigh, and another from the Lumbee Film Festival. We had an outdoor screening in Hoke County, North Carolina. We've had screenings in Knoxville, Tennessee, and in Raleigh for an environmental justice conference. Very different types of audiences.

The reception has been much like what you've just said: it makes viewers sad and hopeless, sometimes it makes them feel angry all over again. It helps us understand why we’re on the journey that we’re on. If we can understand how this history came about, we can do something different about it. The people who have who have told me that they resonate with Lumbeeland the most are people on a recovery journey of their own.

Some people come up and say, “I'm not certain about why you chose to tell this story. I don't feel comfortable with it.” And then people who say, “I saw myself in mid-journey on the screen. Or, “It made me understand it my situation, made me stronger. My mother and grandmother suffered from drug addiction.” And she didn't want her daughter to go through the same thing. Seeing characters on the screen try to break cycles. Like Dollar with his daughter, Danielle, when he tries to be honest with her — “Your mother's not here, but I'm here for you.”

Another Robeson County collaborator said, “If you want this to touch on what we're going through right now, you have to address the epidemic of opiods. We need to see the characters meeting the consequences of their actions.” If we didn't have the ending that we have, it wasn’t going to feel like a true picture.

Southern Spaces: Music is very important to Lumbeeland. How did you make the choices?

Lowery: There are several musical moments that connected for me when I was writing the story. The process gave me a greater appreciation for how rhythm influences writing. In key scenes, there was always some song in the back of my mind. At the opening church service, I didn't think it would necessarily be “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?,” but I've spent a lifetime in Lumbee churches with that type of piano gospel.

Because Dollar is trying to break a cycle, what is the music of our culture that gestures towards closeness and intimacy, but also allows an appropriate distance? It's not like in a Western or mainstream American film in which the only kind of love you get to see is romance or it's a hug plus cry, a formulaic thing. So if a father and daughter are going to share an intimate moment, what's the rhythm of that? What immediately occurred to me was the two-step powwow song where you'll see fathers and daughters, or mothers and sons, or couples, teenage, older, whatever dancing that song around the arena. And I reached out to a hometown drum group, Southern Sun Singers, for one of their recordings. My family has known their founders for thirty years or more, and they granted us the rights to use the song.

Another moment was my late husband, Willie French Lowery, singing, “Great Day in the Morning,” that launches the last act.

We needed a rhythmic shift because we have to go from one character spying on another to a birthday party. We needed a strongly structured song that would have the right tone, but a contrasting tone. Willie was a great songwriter. His songs are exquisitely structured. And I really like the lyrics:

Great day in the morning.

It's coming without a warning.

Ain't no use to getting all upset.

That's one of the things that influenced the emotional tone of the story. It’s my grandmother's saying that if it's not one thing, it's two. Plus we could get the rights to that song because I am the steward of Willie’s music catalog right now. So many people helped with small but crucial things along the way — the record company Paradise of Bachelors, re-released Willie’s first album in 2012 and their owner, Brendan Greaves, did the research on Willie’s archival recordings and pointed me to that song. It’s perfect.

And then, “Keep My Memory,” which was a song by Alexis Raeana, Charly Lowry, and Wylie Withers written in remembrance of murdered and missing indigenous women. I always had in the back of my mind for the ending. This issue is typically talked about as a legal jurisdictional matter, of women whose murderers slip through the cracks. But we often know who kills our women. It's not a mystery. In our community, so much of the harm we experience because of patriarchy is at the hands of our own family members. That’s the thrust of “Keep My Memory,” the rhythm, the instrumentation, the lyrics, the melody. It struck me as the right song choice. It's a bit beyond genre, very contemporary.

Most of what we see about Native people in film and video is about the past. It's rare that you have “now.” Lumbeeland wasn't made in response to Reservation Dogs, but it was being made while Reservation Dogs was on TV. We're always living with the question of how do we make our contemporary realities visible? I think that song “Keep My Memory” does that. And personally it was satisfying to position the music of Alexis (who knew Willie and whose parents knew him well) next to his.

But mostly the music has to work because it feels right. And there's no other reason.

Southern Spaces: And the film’s final scene? It’s not a clean resolution, but a moment that opens up questions.

Lowery: I like films that do that. It was written as a bit of a cliffhanger. You hear a knock on the door. But you don’t see who’s there. The scene suggests that the story’s not over. Is this a pilot for a series or a feature? We don't know. But we want people to wonder what happens to this family. The ending felt true to me. I don't like resolved endings. I want to have more questions than I have answers.

About the Authors

Malinda Maynor Lowery is a historian and documentary film producer who is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. In July 2021 she joined Emory University as the Cahoon Family Professor of American History.

Steve Bransford is senior video producer at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship.

Allen Tullos is co-founder and senior editor of Southern Spaces.

Recommended Resources

Text

Duval, Kathleen. Native Nations: A Millennium in North America. Random House, 2024.

Lowery, Malinda Maynor. The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle. University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Emanuel, Ryan. On the Swamp: Fighting for Indigenous Environmental Justice. University of North Carolina Press, 2024.

Web

Brave NoiseCat, Julian. "Who's Your People?" The Assembly, October 4, 2022

https://www.theassemblync.com/culture/lumbee-tribe-federal-recognition/

Carolina K12 on Indigenous Life and Cultures.

https://k12database.unc.edu/lesson/?s=&lesson-topic=indigenous-life-culture

Emory Libraries Guide to Southeastern Native Nations

https://guides.libraries.emory.edu/c.php?g=334874&p=8393409

Lumbeeland. First Nations Experience. 2024. Available for streaming at no cost. Thirty minutes.

https://fnx.lightcast.com/player/57451/729600