Overview

Mark Auslander and Avis E. Williams recount the contested circumstances surrounding the naming of "Dried Indian Creek" in Newton County, Georgia and explore the lingering racial and institutional implications of this geographic history.

Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope—a faith in the ultimate justice of things. The minor cadences of despair change often to triumph and calm confidence. Sometimes it is faith in life, sometimes a faith in death, sometimes assurance of boundless justice in some fair world beyond. (W.E.B. DuBois, "Of the Sorrow Songs," The Souls of Black Folk)

For generations, African American families in Newton County, Georgia have told a haunting story about a tributary of the Yellow River known as "Dried Indian Creek," which meanders about ten miles through the municipalities of Oxford and Covington. The creek passes about a half mile east of the original campus of Emory College—founded in 1836, now known as Oxford College of Emory University—and directly past Bethlehem Baptist Church, the county's oldest African American house of worship. For two centuries the waterway has been a significant site of fishing, trapping, hunting, gathering, reflection, baptism, and recreation for the county's Black residents.

Local Black families are well aware of the white narrative about the name of the creek, published in multiple sources across the decades: when settlers came into the lands that would become Newton County (founded in 1821), they encountered the mummified remains of an individual, whom they assumed to be Native American, and named the waterway "Dried Indian Creek." This version was often told by the segregationist sheriff of Newton County, Henry ("Junior") Odum, (1915–1976), whose grandfather had established "Avon Indian Farm" near the creek. In Sheriff Odum's telling, the mummified Indian was discovered "stretched out under a big old tree."1Odum's account is quoted in a laudatory article about the sheriff in the Atlanta Journal Constitution, 26 May 1968, p. 172.

The African American narrative is different. Elders we have known recalled that when they were children in the 1930s, their elders told them that the creek's name bore witness to a terrible crime. When whites arrived, a courageous Native American leader refused to leave the land his people had long resided on.2We assume this Indigenous leader was Muscogee, but the older African American oral accounts we heard referenced him as "Indian" or "Native American." White settlers seized, beat him, strung him up, and left his body dangling over the water, not allowing anyone to cut him down until his corpse had dried. As the story was told, this early spectacle lynching was staged as a warning to Native and enslaved Black people that any challenge to white rule would be swiftly and violently put down.

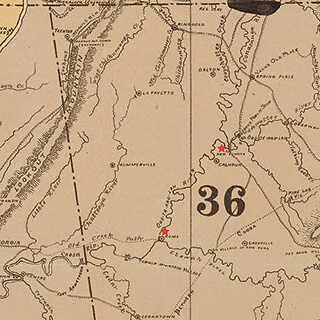

We know of only one white-authored account. The June 4, 1893, Atlanta Constitution reports that a Mr. W.D. Boggus of Covington has a number of curiosities on display in his place of business, including ". . . the leg bone of the Indian chief who was hung in 1795 and left to dry, near the old mill here in town, and from which incident Dried Indian Creek got its name."3Newspaper accounts from the following year state that Boggus wore a ring made from the "bone of an Indian warrior," exhumed from a plundered burial site near Covington (Macon Telegraph, 16 March 1894, p. 4). The individual in question, Woodson D. Boggus (c. 1868–1936), worked in the early twentieth century in Waco, Texas and in Payne, Oklahoma as an oil lease broker before returning to his home state of Georgia. (During the mid-1790s the area that is now Newton County was contested between Muscogee (Creek) inhabitants and encroaching white Georgians.) The Constitution article references the former site of Floyd's Mill, near where Bethlehem Baptist Church now stands, just north of the Clark Street bridge over the creek.

Overlapping Presences: Indigenous and Enslaved

No one we have spoken with recalls the name of this murdered Indigenous man, but the elders shared the belief he was distant kin to many African American families in Oxford. Most of these families trace their descent to two enslaved Native individuals, whom they believe to have been Muscogee (Creek). Cornelius Robinson (born c. 1836) was the enslaved valet of Alexander Means (1801–1883, Emory's professor of natural sciences, who during 1854–1855 was the College's president). Angeline Sims (born c. 1835) was enslaved with her husband George Washington Sims and their children, by Richard Sims, a founding member of Emory College's board of trustees and a founding commissioner of the town of Oxford. Angeline's daughters mainly remained in Oxford and married into local families; nearly every long-term African American family here traces descent back to one of these "Sims" women.

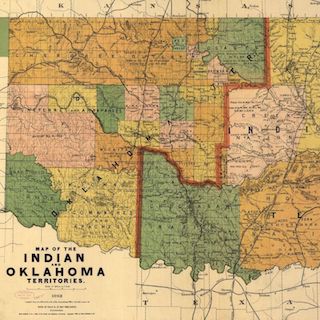

The elders knew that nearly all Muscogee (Creek) had been forced off the local lands around the time of the founding of Newton County, traveling to Alabama and points west, in some cases bringing with them their enslaved people of African descent. Yet they also insisted that not all "Indians" had left, that some intermarried Native and Black families had continued to live in the area.4Newton County, Georgia—created December 24, 1821, from Henry, Jasper, and Walton Counties—was based in three ceded Native territories. Under the terms of the 1805 Treaty of Washington, the 1818 Treaty at Creek Agency, and the 1821–25 Treaty of Indian Springs, all Muscogee lands in Georgia were ceded.

The late educator Emogene Williams (1931–2020), her mother "Miss B," and great-grandmother Sarah Baker Nelson recalled that there was an informal "Indian settlement" to the west of Covington, near Turner Lake, which persisted into the early twentieth century, when the Indigenous people were finally forced off the land. (As they remembered, there were also "gypsies" living in this settlement, who were also forced by whites to leave.) Local historian Johnny Johnson recalls that his grandmother Odessa Smith Gaither, born in 1885, shared stories about Native Americans who passed through Newton County when she was a girl, settling for a while and then "moving on."

A cluster of Afro-Native families continue to reside, semi-autonomously, along the Alcovy (Ulcofauhatchee) River, a couple of miles east of Oxford. (Large Creek villages are known to have been based along this watercourse in the eighteenth century.)5The 1805 Treaty of Washington between the United States and the Creek Nation references the "Ulcofauhatche" river; the term was used through the nineteenth century and was later anglicized to the "Alcovy" River. RaeLynn A. Butler, manager of the Historic and Cultural Preservation Department of the Muscogee Nation, notes that the Mvskoke spelling of the river would be: "orko ofv hvcce," meaning Pawpaw ("Orko," pronounced oth-go), river, or stream. Non-natives, she explains, must have heard "al-co" when mvskoke speakers were saying "oth-go" (RaeLynn A. Butler, personal note to author). See also Jonathan S. Tonge, Ulcofauhatchee: A Guide to Life Along the Alcovy River. Covington: Georgia Wildlife Federation, 2011. This small community of Angeline Sims's collateral descendants, her descendants recall, lived along the Alcovy upstream of the railway trestle, and defined themselves as "Indian" well into the twentieth century.

The late John Pliny ("J.P.") Godfrey, Jr. (1936–2020), great-grandson of Angeline, often visited this settlement of his kin when he was a child in the late 1930s and early 1940s. They trapped, fished, and minimized interactions with local whites. He remembered the elders would sing beautiful songs as they gazed out along the water, with words that were a mixture of English and "old Indian." The songs reminded him of "old Negro spirituals," but were somehow different. He sometimes understood them to be singing in remembrance of the ancestor, the old chief, who had been hanged by whites over the nearby stream and left to dry in the sun. Yet, he recalled, he never heard these elders express bitterness. "They just told me they were singing to help keep the waters rolling along." He smiled, "That's what they felt. Singing somehow helped the river, while the river gave them life and shelter."

Years later, J.P. and Mark walked along stretches of the river, but could find no trace of the old settlement he recalled from his childhood. "It's as if they were never here," J.P. sighed.

J.P and his cousins noted that most Black people in Oxford didn't talk much about their Indian relatives, but he did remember a story about his great aunt Minerva, Sallie's sister. "She was very strong willed. One time, she took her whole family down to live in Louisiana, in 'Ouachita' . . . She used to tell her children there was once a great city there, long before white folks ever came to America. They built pyramids there, just like the ancient pyramids." Records suggest that Minerva, her husband Tom Anderson, and their children lived in Ouachita from around 1890 to around 1908, when they returned to live in Oxford.

Years later, we read about archaeological excavations conducted in Ouachita, Louisiana, indicating that middle archaic mounds and earthworks at Watson Brake dated to at least 3400 BC. J.P. wondered just how Minerva could have known what she had known.

Founding Act of Murder

From time to time, the story of the murder at Dried Indian Creek has resurfaced in our conversations about the early history of Emory College and Oxford, where so many ancestors of local African Americans had been enslaved from 1836 until the end of the Civil War. Deacon Forrest Sawyer, Jr.—who had led the movement for desegregation in Newton County in 1970, famously defying Sheriff Junior Odum—said of Dried Indian Creek, "This county was founded with an act of murder. They were demonstrating the price that would be paid by anyone, red or black, who dared oppose white rule."

Emogene Williams, who traced her descent back to early enslaved persons and white slaveowners in Newton County (and who was the mother of this essay's co-author Rev. Avis Williams) concurred, "That is how they kept power in this county, through public demonstrations of violence, going all the way back to Dried Indian Creek. Lynchings, public executions of Black men scheduled as Black people were filing by going to church on Sunday."

J.P. Godfrey, Jr., whose grandfather Israel Godfrey had worked the land around Oxford in slavery and freedom, remarked, "I don't think it was entirely coincidental that Emory was founded right in the shadow of where that Indian chief was murdered . . . They wanted to show that they had taken hold of this land, and what would happen to anyone who opposed them."

These elders drew a direct link from the public desecration of the body of the murdered Indigenous man in the 1820s to the July 1946 mass lynching by about fifteen white Klansmen of two young African American couples at Moore's Ford on the banks of the Apalachee River in Walton County, which sent terrible shockwaves through surrounding Black communities in the early postwar period.

As Deacon Sawyer put it:

Rivers are the life blood, the arteries, of our land here. Rivers and streams were sacred for Indians, and it was those same creeks we'd steal away to, to feel the flow of the Holy Spirit—from the day we were brought to this county in chains. Of course, white folks chose to torture and kill our people along the river bank, reminding them that nothing was sacred. Any bond of family, any tie of love, could be broken in a moment. That's what white power was back then, and it still is.

Distant Kin: Black Oxford and the Creek Freedmen

These elders had long been fascinated by the stories of the Creek Freedmen, descendants of persons enslaved by Creek slaveowners, who had lived in Georgia and Alabama and then been removed to Indian Territory, later known as Oklahoma. Although there is no direct evidence of common ancestry between Oxford's present-day African American residents and the Creek Freedmen of Oklahoma, many local Oxford Black elders have felt a deep sense of moral kinship with the Freedmen. J.P. Godfrey, Jr., noted, "I know in my heart, those are our people. They were taken from these lands, suffered in ways we can't even imagine, but they endured. They're still our kin."

For J.P. and Emogene Williams, the 1979 de-citizenship of Creek Freedmen—descendants of those who had been enslaved by Creek slaveowners—was particularly painful. As J.P. remarked, "So many thousands gone from here. We had hoped our kin, though in bondage to the Creek, would have finally found a safe harbor in Oklahoma. Now we hear they were expelled, for supposedly being 'too African' . . . For our folks, you might say, the trail of tears never ended."6The precise motivations behind the 1979 changes in the Muscogee Constitution remain deeply contested. Defenders of the 1979 Constitution maintain the change in tribal citizenship was motivated by a desire to recognize only those Creek persons with sufficient Creek blood quanta as Creek citizens. Creek Freedman activists, in turn, insist the disenrollment of the Freedmen was motivated by racial animus, and illegitimately expelled many people whose ancestors had been considered Muscogee for multiple generations. Emogene observed, "I don't know how we're related, but I know from my mother and great-grandmother our people were all mixed together. It pains us to see those folks out West treated with such disrespect. Just like it was happening to us here."

Community members watch as leading figures in the Biden administration and the Congressional Black Caucus advocate for full citizenship rights being restored to all the Five Nation Freedmen. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland in May 2021 approved a revision in the Cherokee Nation constitution restoring citizenship status to Cherokee persons of African descent, and indicated her expectation that Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole would recognize their "moral and legal obligations to the Freedmen."

By the Rivers of Babylon

In 2021, Emory University hosted a conference devoted to tracing the legacies of enslavement and the dispossession of Native American lands on the grounds that later became the institutions that comprise the consortium "Universities Studying Slavery," including Emory, University of Virginia, the Virginia Military Institute, Georgetown, Rutgers, UNC Chapel Hill, and Brigham Young University.7"Program Schedule." In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession: Emory, Racism, and the Journey towards Restorative Justice. Emory Libraries. Accessed February 3, 2022. https://libraries.emory.edu/slavery-symposium/program-schedule.html. The conference opened with a painfully beautiful Muscogee hymn, "Espoketis Omes Kerreskos" ("This may be the last time, we do not know"), sung by Chebon Kernell, a mekko or ritual leader in the Muscogee (Creek) tradition, and a prayer by Rev. Avis Williams, an ordained Baptist preacher and daughter of the late Emogene Williams.8"Acknowledging the Ancestors with Readings, Music, and Prayer." Emory University. October 13, 2021. YouTube video. 1:13:29. The blessing and song by Cherbon Kernell and the blessing by Rev. Avis Williams are found at (00:00–11:30). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELGjnpgdgJE&list=PLDSBylqXf9oGHja1c3mknOqz8JcVYMNfT&index=6. "Espoketis omes," which resonates with an African American spiritual, was sung along the Trail of Tears, as Muscogee families, including enslaved persons of African descent, made their way towards an uncertain future in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma).9The history of the song "Espoketis Omes Kerreskos" is explored in the 2014 film This May Be the Last Time (dir. Sterlin Harjo). More broadly, the film engages with the intertwined histories of Scottish Congregational line song, African American spirituals, and Muscogee (Creek) songs. Black spirituals and Muscogee hymns draw upon congregational line or note singing, part of a long musical and spiritual trajectory to maintain community amid wrenching dislocations.

Hearing Chebon sing, Avis was struck by the many parallels to the "sorrow songs" she grew up with in the Black Baptist tradition.10W.E.B. DuBois, "Of the Sorrow Songs," The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1903. Wikisource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Souls_of_Black_Folk/XIV. In the first chapter of African Creeks (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), Gary Zellar notes that early Christian missionization and evangelism in the Creek Nation in Georgia and Alabama was primarily associated with persons of African descent enslaved in Muscogee (Creek) communities. Had her ancestors and Chebon's ancestors perhaps sung together in the past, before or during the terrors of enslavement, forced removal, and land alienation? She was reminded in particular of Psalm 137: "By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept/when we remembered Zion . . . our tormentors demanded songs of joy/they said, Sing us one of the songs of Zion!" Her ancestors, she knows, sang songs of sorrow but also of hope, in a strange land. So too, she thought, would Muscogee, including enslaved and free people of African descent, have sung these hymns, along many waterways, as they were expelled from their homelands.

On October 10, 2018, a Muscogee Methodist delegation gathered at the long-ago site of Standing Peachtree (Pakanahuili), the Muscogee (Creek) village that stood where Peachtree Creek enters the Chattahoochee River near present-day Buckhead, in north Atlanta.

They offered a prayer and hymn over the river. In a concluding commentary, Marilyn Cloud explained that in Muscogee tradition, "You add the prayer to the tobacco, because it is sacred. You put the tobacco in the flowing water. Whatever the prayer is that you make, the flowing river carries it."

Recently, we've held conversations about how these long-separated people might enter into dialogue. There are many unresolved legacies to work through, including the status of the Creek Freedmen, who are denied basic rights of tribal citizenship. Creek scholar and activist Craig Womack suggests music might be an appropriate starting point, to share and learn, and to hear voices of ancestors tied to riverscapes and landscapes that descendants consider sacred. Perhaps Muscogee and Newton County African American family members might gather along the river bank, joining in old hymns to honor the ancestor murdered long ago and left hanging over the waters, even as their voices, raised in song, help to move the river along.

About the Authors

Rev. Avis E. Williams, a community activist based in Newton County, Georgia, holds four degrees from Emory University (AA, BA, Master of Divinity, Doctor of Ministry). She works for the Putnam County Charter Public School System, and currently serves on the Oxford, Georgia, City Council.

Mark Auslander, a former faculty member at Oxford College of Emory University, is a visiting faculty member in anthropology at Boston University and University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for detailed comments on earlier versions of this essay from Craig Womack, Professor Emeritus of English at Emory, RaeLynn A. Butler, Manager of the Historic and Cultural Preservation Department, The Muscogee Nation, and Allen Tullos. We have benefited from guidance on Five Nations Freedmen perspectives on this complex history from Eli Grayson and Marilyn Vann. We acknowledge the teachings of many elders from the Newton County African American community, especially the late Emogene Williams, Sarah Mitchell Wise, Sarah Francis Hardeman, Mary Gaither McClurkin, Forest Sawyer, Jr., and John Pliny (J.P.) Godfrey, Jr.

Cover Image Attribution:

"A new and accurate map of the province of Georgia in North America," London, England, 1779. Map courtesy of Library of Congress.Recommended Resources

Text

Auslander, Mark. "Dreams Deferred: African Americans in the History of Old Emory." In Where Courageous Inquiry Leads: The Emerging Life of Emory University, edited by Gary S. Hauk and Sally Wolff King, 13–21. Atlanta, GA: Emory University, 2010.

Carson, James Taylor. "The Obituary of Nations: Ethnic Cleansing, Memory, and the Origins of the Old South." Southern Cultures 14, no. 4 (2008): 6–31.

Chaudhuri, Jean and Joyotpaul Chaudhuri. A Sacred Path: The Way of the Muscogee Creeks. Los Angeles: UCLA American Indian Studies Center, 2001.

Tonge, Jonathan. Ulcofauhatchee: A Guide to Life Along the Alcovy River. Covington: Georgia Wildlife Federation, 2011.

Womack, Craig. Art as Performance, Story as Criticism: Reflections on Native Literary Aesthetics. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

Zellar, Gary. African Creeks: Estelvste and the Creek Nation. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

Web

Harjo, Sterlin, dir. This May Be the Last Time, DVD. Tulsa, OK: This Land Films, 2013. http://www.thismaybethelasttime.com/.

"In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession: Emory, Racism and the Journey Towards Restorative Justice." Symposium held at Emory University, Atlanta, GA. September 29–October 1, 2021. https://libraries.emory.edu/slavery-symposium/.

Treaty Between the United States and the Creek Indians Signed at Washington, DC. Washington, DC: National Archives, 1805. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/161378334.

"Universities Studying Slavery." President's Commission on Slavery and the University. University of Virginia. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://slavery.virginia.edu/universities-studying-slavery/.

Womack, Craig, Marilyn Vann, Eli Grayson, and John Parris. "Freedmen Claims in Relation to McGirt vs. Oklahoma: A Panel Discussion on the Historic 2020 Supreme Court Decision." Michael C. Carlos Museum, Atlanta, GA. March, 30 2021. YouTube video. 2:12:42. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T5_WsDaQYAo.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Odum's account is quoted in a laudatory article about the sheriff in the Atlanta Journal Constitution, 26 May 1968, p. 172. |

|---|---|

| 2. | We assume this Indigenous leader was Muscogee, but the older African American oral accounts we heard referenced him as "Indian" or "Native American." |

| 3. | Newspaper accounts from the following year state that Boggus wore a ring made from the "bone of an Indian warrior," exhumed from a plundered burial site near Covington (Macon Telegraph, 16 March 1894, p. 4). The individual in question, Woodson D. Boggus (c. 1868–1936), worked in the early twentieth century in Waco, Texas and in Payne, Oklahoma as an oil lease broker before returning to his home state of Georgia. |

| 4. | Newton County, Georgia—created December 24, 1821, from Henry, Jasper, and Walton Counties—was based in three ceded Native territories. Under the terms of the 1805 Treaty of Washington, the 1818 Treaty at Creek Agency, and the 1821–25 Treaty of Indian Springs, all Muscogee lands in Georgia were ceded. |

| 5. | The 1805 Treaty of Washington between the United States and the Creek Nation references the "Ulcofauhatche" river; the term was used through the nineteenth century and was later anglicized to the "Alcovy" River. RaeLynn A. Butler, manager of the Historic and Cultural Preservation Department of the Muscogee Nation, notes that the Mvskoke spelling of the river would be: "orko ofv hvcce," meaning Pawpaw ("Orko," pronounced oth-go), river, or stream. Non-natives, she explains, must have heard "al-co" when mvskoke speakers were saying "oth-go" (RaeLynn A. Butler, personal note to author). See also Jonathan S. Tonge, Ulcofauhatchee: A Guide to Life Along the Alcovy River. Covington: Georgia Wildlife Federation, 2011. |

| 6. | The precise motivations behind the 1979 changes in the Muscogee Constitution remain deeply contested. Defenders of the 1979 Constitution maintain the change in tribal citizenship was motivated by a desire to recognize only those Creek persons with sufficient Creek blood quanta as Creek citizens. Creek Freedman activists, in turn, insist the disenrollment of the Freedmen was motivated by racial animus, and illegitimately expelled many people whose ancestors had been considered Muscogee for multiple generations. |

| 7. | "Program Schedule." In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession: Emory, Racism, and the Journey towards Restorative Justice. Emory Libraries. Accessed February 3, 2022. https://libraries.emory.edu/slavery-symposium/program-schedule.html. |

| 8. | "Acknowledging the Ancestors with Readings, Music, and Prayer." Emory University. October 13, 2021. YouTube video. 1:13:29. The blessing and song by Cherbon Kernell and the blessing by Rev. Avis Williams are found at (00:00–11:30). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELGjnpgdgJE&list=PLDSBylqXf9oGHja1c3mknOqz8JcVYMNfT&index=6. |

| 9. | The history of the song "Espoketis Omes Kerreskos" is explored in the 2014 film This May Be the Last Time (dir. Sterlin Harjo). More broadly, the film engages with the intertwined histories of Scottish Congregational line song, African American spirituals, and Muscogee (Creek) songs. |

| 10. | W.E.B. DuBois, "Of the Sorrow Songs," The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1903. Wikisource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Souls_of_Black_Folk/XIV. In the first chapter of African Creeks (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), Gary Zellar notes that early Christian missionization and evangelism in the Creek Nation in Georgia and Alabama was primarily associated with persons of African descent enslaved in Muscogee (Creek) communities. |