Overview

Michelle Fishburne's Who We Are Now: Stories of What Americans Lost and Found during the COVID-19 Pandemic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023) is an edited collection of interviews recorded in-person across the US between September 2020 and September 2021. Asking only one question--What was your 2020 supposed to be like and what did it end up being?--Fishburne documented a range of vivid Covid encounters. Southern Spaces presents seven of these narratives prefaced by an edited conversation between Fishburne and three members of our Covid series team: Mary Frederickson, Abigayle Mazzocco, and Allen Tullos.

Southern Spaces: Oh, here's Michelle now. Are you in your RV?

Michelle Fishburne: Yes, I am. As a matter of fact, I'm in the RV at Jordan Lake State Park near Chapel Hill. It's about ten minutes from where I raised the kids. I have a twenty-three-year-old who has struggled with long COVID, but has just graduated from UNC. And then we'll go up to Princeton, New Jersey, where I grew up. I'll be housesitting for two weeks.

Q: We've been intrigued by your book, Who We Are Now. It's an important project. The interviews hit powerfully with regard to the loss and heartbreak from COVID. Sometimes now, in the wake of the pandemic, it's possible to think it wasn't really that bad. Life goes on. But going back to the beginnings and to the following many months as you do, the power of this pandemic can't be avoided.

Let's start with what were you doing when it became evident COVID had arrived and was not going away. What were the early months of COVID in 2020 like for you? When was it evident that COVID was not going to be a two week, stay-home-and-then-go-back-to-life-as-normal situation? And how did you develop the project that ultimately became the book?

Fishburne: I think that moment when I realized this was going to last more than two weeks takes me into early April. In January, I had just gotten back from a wonderful vacation in Grand Cayman and I had told everybody all over holiday break how much I was enjoying my job and that I could just pinch myself. It was just a great job. I was a public relations partnership person for Inmates to Entrepreneurs, some people who really, really needed it. I was working on an event at the US Senate and the House of Representatives. We were talking to John Legend, who was working on something similar, about going into a prison with him.

And then on January 17, an unknown virus attacked my eighth cranial nerve and I lost my hearing in my right ear and my vestibular functioning. I began using a walker and learning to adjust to life without hearing in one ear. In February, I bought a prom dress for my senior in high school. She was very excited about the prom and we were waiting to hear back from colleges.

Then my boss, when he saw COVID coming, he was having some struggles. His doctor said to him, "You know, you can't go anywhere." And so he said to me, "I'm going to have to lay you off because I can't go do any of these things that you are preparing." So I was laid off and I thought, "No big deal. I have a law degree from UVA. I have had an illustrious career. I've done wonderful things. I'll find a job." I wasn't panicked. But I submitted eighty-six customized cover letters between the middle of March and the middle of July, and I had nothing.

The lease on the post-divorce house was coming up on July 31. I knew that on August 1 I would have no house, no spouse, no job, and no kids to take care of. And the big critical moment happened in a Target parking lot on June 15, when I had to decide where to have the movers put my stuff. I thought, "What doesn't make any sense for me is to rent a place because I have no idea where I'm gonna have to go to get a job. I've got the motorhome that I homeschooled my kids in for ten months once. All right, I can move into the motorhome." So I put everything in storage.

And then I thought, "Oh, what will I do? Well, I love the Outer Banks. Take the motorhome to the Outer Banks." But then I thought, "Michelle, you can be in hell while you're in paradise. And if you're waking up every day thinking what's your next job, you're kidding yourself. You need a project."

I could drive out to Yellowstone from North Carolina because I've done it before. Yeah, and then I will cry the entire time I go to national parks because I won't be with my little ones anymore and I'll be all by myself.

Then out of the blue came the idea of Humans of New York. And I thought, "Oh, Brandon Stanton interviewed thousands of people in New York, took their photo, got a little snippet of their story, put it on social media." I could do the same thing. I could do Americans of the pandemic. Who We Are Now—that was the name right from the beginning.

I know that when you focus on other people, it's easier not to be afraid. I also know now from somebody I met during the interviews that action is the antidote to fear.

Getting in the motorhome and doing a fast run helped with my fear. And focusing on other people helped with a different kind of fear. But I was also very naive. What made me think I could go out in the middle of the pandemic and find strangers to talk with?

Q: Your project started off the way interviews work. One person leads to another. But you say that your fear did not seem to have been pandemic related. We're wondering, weren't you concerned about catching the virus?

Fishburne: I wasn't. Once again, naivete really helped. I thought, "I'll just wear my mask and I'll be smart. I mean, I could be smart in Chapel Hill. Why can't I be smart in Saint Louis or New Mexico?" But what I found when I got out into parts of the country that were sparsely populated, I started to reconsider what critical thinking meant.

I did take some risks. I'd think, "Okay, this building is big enough and it's just me and this person. They're way over there and I'm way over here." Because if somebody is going to tell you a story, and they've just met you, and it's about their lives, especially since I only ask one question, what I really needed was for somebody to keep going and going, going and going, right in my face. Inviting them to continue and showing interest. The mouth is really important to that. As much as I tried to use just part of my face and some body language, there were times when I needed to take off the mask.

Q: That makes perfect sense. So you talk about how this book got started, but then you traveled a long road. How did you have the momentum to sustain the project?

Fishburne: It became something unto itself. I'm just a project person and I got in the groove. What sustained me was how surprised I was every single time I got to listen to somebody else. I mean, there were genuine moments of surprise in every single interview. For example, when I talked with Anne, who's the wedding planner in LA, I had in my mind all these questions I was going to ask her because I was interested in how weddings had changed. But when I asked her the one question, she went off in a completely different direction that surprised me.

I think the excitement of knowing I was going to hear somebody else's story is what sustained me.

Q: Who was most helpful in encouraging and supporting you?

Fishburne: My mother, who is now eighty-five, was my sounding board and supporter. She also is an editor. I would send her transcripts of the interviews. I would think, "Well, this person's got different parts of their story in different places in this transcript." So I would move it around then send it back to the person and ask, "Is this what you said?" Or they'd say, "Yes, that's pretty much what I said. Or, "I said 'like' too many times. Can you take that out?"

My mom has a PhD in sociology from NYU. I grew up knowing about qualitative and quantitative research. Knowing how you ask the question is so important. We talked about the question a lot. And I needed to have a grid, a mosaic, to do a representation of the US as best I could. We talked about that, too.

Q: How did you organize your project? And, to get a sense of the scale and the scope of all the interviews you did, how much is included? How much is left out? How did you edit?

Fishburne: I was conscious of what was going on geographically. Age, race, gender, class, they're all in the mosaic. Urban, suburban and rural. Religion of different kinds. There's New York City and there's Jackson, Mississippi. I used a reverse order of population of the top fifty cities to make sure that I got different types of urban places in different parts of the country.

One area I leaned into heavily was the performing arts because they rely on a live audience. And other vocations that really had a hard time. I overloaded those a bit because they were compelling.

I interviewed about three hundred people, but only a hundred are in the book. There are more on the website and there are more that never made their way into a story. One of the peer reviewers called the book "elegiac," not a word I had anticipated. He had seen the book without any photos. Originally the contract was for forty photos, but one hundred people. And I thought, "I don't know how I'm going to choose which forty people." This was December 2021. My editor at UNC, Lucas Church, said, "Maybe we shouldn't have photos in the book. Then it would be elegiac." So the book went without the photos; the way it's set up, it kind of tumbles.

In order to get that tumble feel, some of the stories had to be very short. For example, I spent two hours with Luke and Rodney and only used Luke's story about how he got more grief for wearing a mask than holding the hand of his partner. Lucas said the stories need to be between 250 words and about 1,200. The average interview was probably thirty-five or forty minutes. If the average story length is six-hundred words, which takes about three to five minutes to say out loud, the book has about five hundred minutes of material. And I recorded three-hundred times thirty minutes. A lot was left out.

When Who We Are Now was published—I'm just going to say the truth—it did not do very well. We think what happened is that it arrived during COVID exhaustion. Yeah. More recently, the couple of book clubs that have used it have really delighted in it because it helped them reframe what the pandemic was. I know that however-many-years hence everything that I gathered is going to have more value than it has today. I think in seven years, when I'm sixty-seven, I'm going to be a very popular lady at the ten-year anniversary.

Q: As a historical read as compared with a contemporary read, I think you may not have to wait that long.

Fishburne: Sometimes when I pick it up and I read it—like I just opened up to Tina, the grief counselor—it washes over me. It all just comes back and you think, "Oh, yes, we had to go through that. How do you grieve when you can't have the formal process?"

And then when I was re-reading Tina's story, Melissa's story in Corinth, Mississippi came flooding back. Her mom had died during COVID. And Melissa said to me, "I've always thought it odd when a family member passes and you go back to the home and you have the whole spread of food that people bring. I never understood the importance of it until now. Because now when I walk down the street, it can be a beautiful day, months and months after my mom has passed and I'm having a good day and somebody who hasn't seen me since my mom passed will say, 'Melissa, I am so sorry about your mom.' I didn't get the kind of closure you get with everyone there eating food, drinking, talking."

And in a way that's how it was with COVID itself. It came, peaked, and petered out, but we never had the "end," even though the federal emergency was over. But it's not the end. Especially for people with long COVID.

Q: You mention that Who We Are Now came out around the time of COVID fatigue. But how did these oral histories affect you? Did you compartmentalize them as research?

Fishburne: I didn't see the project as research. It was just my life. Even now, when people talk about the pandemic, most people talk about it in ways that are very foreign to me. And the way I talk about it is very foreign to most people. Before I got in the motorhome and drove around the country, I thought I knew the pandemic experience, but that was based on my own lived experience. When I left here in September 2020, I expected to find desolation, depression, and division. I expected it to be very, very negative. What really surprised me was the human tenacity. The pluck. And that's the word that I use now a lot, pluck, which is spirited and determined.

In doing the interviews, I settled on asking only one question: What was your 2020 supposed to be like and what did it end up being? And people could talk about what they wanted to. They talked about what really mattered to them, what really defined this period of time, and what made it very difficult, or challenging, or surprising.

People who were out in areas that are sparsely populated would say, "Oh, I just went on the same way." But I know having been there, that every person was changed during the pandemic. More than normally every person genuinely thought about other people and what they were going through. And then there were people who were not given anywhere near the support they needed.

Q: And what do you say now, with a bit of distance, in terms of the perspective that you have?

Fishburne: My mom keeps telling me that I'm a sociologist and I keep pushing back and saying, no, I'm a collector of stories because a sociologist goes back and looks writ large. And I don't feel qualified to do that. I centered the project on individuals and offered up each story.

Many people had very difficult experiences of having to go in and try to do their jobs under incredibly hard circumstances. Often, they didn't have the equipment, didn't have the guidance, didn't have the support. They were watching people die or people turned people away. They couldn't do the jobs that they had trained to do. Then people would come in and reject what they were trying to do or tell them they were wrong. That was head spinning. Or to walk into a store and nobody would have masks on because it was a state where you didn't need to have a mask. It was like a horror movie. They'd think, "Which one of you am I going to see next week?" A lot of the people that I talked with in the healthcare field felt like they went through a trauma.

I thought about various groups of people who were struggling. For instance, I talked with Emma, a director of a migrant farmworker nonprofit. She told me about how really nobody cared to protect migrant farmworkers and about one man who died alone in a motel room. That never should happen. In Birmingham, I interviewed Anne, who was running a homeless shelter. She said it got to a moment when she had to ask whether people were safer inside the building or outside.

I had just started eastward in Texas when Governor Abbott announced that you didn't need to wear a mask anymore. I'm like, "What the heck, Texas is a long state to have to go through no matter which way you do it, right up or down or sideways." I was going west to east and had to be in the state for four more days. It became very uncomfortable. I am a political animal so it was really hard for me to not lean into that. But I became so fascinated with each individual. And I thought, "We are all in this together."

But let's take Fox News, on cable all over America right now. And I was really angry at a big part of the country. I'm like, how can you think that way? How can you think that way? It's Fox News. People have had it in their homes for so long. Fox was pitting us against each other, making people angrier and angrier. Some really ugly parts of us came out. But when you actually get in and talk to people, that's not who they want to be. That's not what they want to be thinking about it.

The false narrative that COVID was not as serious as it indeed was really impacted our healthcare workers and public health officials. I interviewed people who had significant responsibilities, including top public health officials in major metropolitan areas, and they stepped away or are in therapy. And some decided not to deal with it affirmatively. One doctor I spoke with recently said, "I can't talk about it." She started the dialogue and then she said, "I can't. I've just put this away in a compartment. I just can't touch it. I just can't do it." But then, there was a nurse who cried at the end of the interview and said, "Oh my gosh, I just really needed to talk about that."

I saw and heard America in these different ways. People trying to get through. It was such an odd time. The challenges we faced were very unusual.

Luke, South Carolina

Mask Wearer—November 2020

We have felt more discriminated against for wearing masks than being gay. And that's crazy. In the United States of America, we are getting more nasty comments said to us in a grocery store, on the street, for the fact that we have a mask on than the fact that we're holding hands as two men. That's just hilariously tragic. Like, that's where we're at? You're really going to be angry that I have a mask on? So no shame or foul to people who don't want to wear a mask—just don't call me a sheep because I have a mask. That literally happened to me at the gas pump this week.

Valerie, North Carolina

State Senator—December 2020

On March 3, I was attending a conference in Charlotte, and I got a text message from Health and Human Services. It was, to put it mildly, surprising to get a text from DHHS out of the blue. They were alerting me that the first confirmed cases of coronavirus in the state of North Carolina were in my district. Two residents of Chatham County who had traveled to Italy had contracted the disease. I knew enough to know that this was huge and that we were on our way into something that was not going to be good. I left Charlotte that day rather than staying over the next night because I knew that if there were two cases, there certainly were more.

When I look back at 2020, coming from that point of entry into where we are now, with massive unemployment because of shutdowns, and then the blowback, the pushback, it has been very, very difficult. We knew the shutdowns were not the best thing for the economy, but having this juxtaposition of the economy versus overall healthy communities was hard. The governor was in a tough position.

And in the midst of all of that, we were waiting on the federal government to bring in aid. When people started to lose their jobs and people's rents and mortgages and car payments went into jeopardy, there was no help. And the state system was not equipped to handle the massive number of unemployment insurance claims. Before COVID, we usually had about 800 or so claims a week. Then all of a sudden, we went from 800 to 1,800 to 300,000.

Our constituents were coming to us saying, "I followed everything you told me, Senator. I filed my unemployment claim and I've waited for three weeks now. When I call, nobody answers the phone. When I go online, I get knocked off. When I do stay online, I keep getting the same thing saying I'm not eligible. I know I'm eligible. I can't pay my rent and my family is going to be out on the street. Can you help me?"

How many of those folks do you think I could help? Very few. And then the small businesses were calling and saying, "Senator, we're not eligible for PPP [Paycheck Protection Program]." Or "Senator, you can only apply through certain banks or lending institutions. I've never done this before. I need technical assistance in applying." Or "Senator, I don't have an established relationship with this bank, so they will not even talk to me. So where's our help?" That's so painful.

And then I got the call that brought everything really close to home. It went like this.

"Hey, Valerie, how are you?"

"I'm good, how are you?"

"Not so good. So-and-so died of COViD."

"No, can't be."

"Yes."

"What happened?"

"Well, you know he had surgery. After the surgery, he was sent to a convalescent center. He contracted COVID there and died in four days."

Two days later, his family asked me if I would eulogize him. The ceremony was on May 2. There was no church service, just a graveside service, because of course we had to be outside. Afterwards, my husband and I just drove around because I just was not ready to go inside. While we were driving, I got a phone call. I had noticed at the funeral that my friend's best friend was not there. Well, so I got the call from another friend who was at the funeral. This is how it went:

"Valerie, I know this is going to upset you, but they found Kenneth dead today."

"What do you mean?"

"That's why he wasn't at the funeral."

He was only two years older than me. Kenneth was the editor and publisher of the Carolina Times newspaper, one of the few Black newspapers in our state. So that's no more. That's the end of an era that started with his grandfather, Louis Austin, way back in 1927.

And so, when I quiet myself, those are the things I most vividly remember.

Frank, Louisiana

COVID-19 Ventilator Patient—January 2021

I was working for a nonprofit organization driving a bus. We would bring older people, people on Medicare, back and forth to doctor appointments, rehab centers. I come home from work, sit down, and watch TV, and all of a sudden, I can't breathe. I called my son and he took me to the hospital. They diagnosed me: "You have COVID." I said, "Man, I ain't got no COVID." The next morning, Dr. M. come and say, "What's the matter?" I'm telling him I come here last night, and the doctor told me I have COVID. I just couldn't breathe. He said, "Are you ready to go home?" I said, "Yeah." So they let me come home. Got home, next day, the same thing. Can't breathe.

They had an ambulance service come get me. They came in here and gave me a breathing treatment and took me to the hospital. And when I got there, on March 24, Dr. M. say he's going to put me in a medically induced coma. I went to sleep on March 24 and when I woke up, it was April 23. I'd been on a ventilator for almost thirty days. The hospital's head of infectious medicine told Dr. M. to unplug me earlier than that, but Dr. M. said, "Man, I'm in the business of saving lives. I'm not going to unplug that man and tell his family he is brain dead, which he's not." When I woke up, I asked my wife when was Easter, and she said, "Boy, Easter been gone." And I say, "Where I been?" And she said, "You been out, asleep." But I didn't remember nothing, and I didn't realize how sick I was until I called my wife and said, "When you come get me?" and she said, "Not right now." I had no idea that I couldn't walk. I had no idea. I couldn't go to the bathroom. I couldn't pull up in the bed. I couldn't use nothing on my body. Hands, legs, feet, nothing. I couldn't do nothing, period, in a vegetative state. I lost the use of everything, man.

They told me they would send me to a rehab center. When I got there, they put me in a room, and the next thing I know, they put me on a second floor by myself and told me that I got COVID again. So I stayed thirty days in there, with everybody masked up, aproned up, gloved up. And they just got me laying there in the bed, can't turn over, can't feed myself, can't do nothing. And nobody could come visit me because I was in isolation. Every time they come in the room, they'd say, "Why are you down in that hole?" "Man, I've been trying to get out of this hole, but I don't have the strength to pull myself up." And then they get mad with you, they'd bring three or four people in and take you out of the hole and then all of a sudden you're back in that hole. Yeah, I mean, I'm laying flat like this for three months. It was supposed to be a rehab center, but they did nothing for me.

I finally got out of there and back to the hospital to do rehab. In two weeks, I was able to stand at the parallel bars and sit in this wheelchair and push up. And then they started walking me, and it was amazing because I hadn't walked in ninety-something days. I got off-balance and never could get the strength. I would walk with a walker and then I would get tired. Like right now, I still get tired fast, I still don't have no balance, still can't taste every now and then, still can't smell every now and then.

I know there's a God 'cause it's a miracle that I am here. The guy's son who does the dialysis tell me, "Mr. Frank, you're a walking miracle." I say, "What are you talking about?" He say, "Frankie, everyone who

was on that floor that had COVID, all of them died but you." And he say, "I know there is a God, you blessed." Then Dr. V., the heart doctor, say, "Man, we really thought you was going to die." Dr. S., "Man, we really thought you was going to die." You know, it's a bad feeling when everybody coming to you, telling you that they really thought you was going to die. And they look at you, "Man, Frank!" and you don't remember. The doctor told me maybe it's good I don't remember. You know? And I'll be asking my wife, "What happened?" And she'll be telling me, and I don't remember. He said, "That's a part of your life that you will never be able to get back." That's fine, I'm here now. I don't wish this on nobody, man.

Emma, Arizona

Migrant Farmworker—February 2021

Our farmworker population start their days at 2:00 a.m., sometimes earlier. Approximately 15,000 to 20,000 of them cross every day, and the lines on the border can be two or three hours long. They leave early so they can make it here in time to get on the bus and be taken to the fields where they harvest the fruits and vegetables that America eats. This area around Yuma is called "America's Salad Bowl." Our organization provides services to our population, including immigration, housing, parenting, chronic disease prevention, and behavioral health. We're always very busy, so when we started hearing the news that this virus was impacting China and how bad it was, we didn't have a lot of time to think about it. We have a small, rural life, so you don't think a lot about whether something international will hit here. You don't think about how interconnected you are in reference to it. Then at the end of January, we had three cases. It was still not a pandemic at that point, and it was just three cases, so we were thinking, Okay, so three cases. We continued business as usual, no additional precautions, just basic hygiene and all that. When the governor issued a shelter-in-place order, we realized this was serious. Shops started closing and people were running around and piling up food and toilet paper.

After our agricultural season ended, a lot of our farmworkers migrated to California, particularly Salinas, San Joaquin, Santa Maria. Then we started hearing about the pandemic hitting them over there, and even some deaths. One man died in a hotel room by himself. The family knew he was very sick. Nobody was visiting him or giving him food or anything, according to the family. The only contact they had was just through the phone, and all of a sudden, he stopped answering. That's how they realized he had died.

During the stay-at-home order, I had a lot of thinking to do about our office here in Yuma. We have thirty employees, and it's important for personal and cultural issues to have direct, one-on-one contact with the individuals we serve. After the two weeks of stay-at-home, we opened the office back up. My husband used to work at the Health Department's emergency preparedness program and helped us understand the precautions we needed to take. We invested a lot of money in plastic safety barriers and hygiene equipment and products, and we had the offices fumigated every two weeks to sanitize them.

Then there was the question of whether to open the doors or lock them and make people knock. But I felt badly for the elderly or the farmworkers who just needed a form to be read or translated or just basic services like that. So I decided that we were going to have to take a risk and open the doors and do whatever we could and pray to God. We were going to face the threats and fight them because we could not be paralyzed; we have to continue serving our population. So we opened the doors. We let people in just two at a time or one at a time to keep as safe an environment for them and for us as possible.

When the agricultural season started back up again in October, the owners of the farms required the workers to wear masks and did temperature checks, but the buses were loaded just the same as before, everyone crowded in. We did two or three campaigns where we went to meet the loading area for the buses at three o'clock in the morning. We provided tote bags with masks, information, gloves, and everything. Our staff was wearing their gowns and PPE, like they were in a hospital. They were there, facing their fears, because what else could we do? One time we gave out about one thousand bags between 3:00 a.m. and 4:30 a.m.

At some point in the pandemic, we were ground zero in the world for the number of cases. The harvest season and the pandemic season collided. Many of the migrants were sick, but they wouldn't say anything. And a lot of them were young, between eighteen and thirty-six, and didn't show symptoms. Migrant workers don't get fringe benefits or sick leave or anything like that, so a lot of them, especially the H-2A temporary workers, didn't want to be quarantined for two or three weeks. So the sick workers wouldn't say anything and then the whole crew would get sick, but they would not say anything. The employers wouldn't say anything either. They wouldn't want the testing to be done for the workers and the workers wouldn't want to be tested, and so there was like this kind of silent agreement. "Don't ask, don't tell, because we need you and you need us." That is what I have been hearing.

Donna, Georgia

Senior Living Community Executive—July 2021

The coronavirus came to our campus on March 13. It was one employee and we sent them home. I then went to my boss, the CEO of our company, and said, "Our best strategy right now is to lock in. We'll ask employees to volunteer to live on campus and we'll reward them. And we will just live on campus with our members. It'll be over in two weeks, four weeks max." He never blinked. He was behind me 100 percent.

We didn't call it "lock out." We "locked in" with our members and we kept the world out. We kept coronavirus out. The gate was literally locked, and the only thing that came in and out of that gate was food deliveries, Amazon packages, and Instacart.

I asked for volunteers from our employee body, and sixty people raised their hands immediately.

They included our director of accounting, our moving coordinator, servers, housekeepers, maintenance, security. I took any volunteer who raised their hand. Ended up being seventy-five. The next step was figuring out where people were going to sleep, how we were going to feed employees, and how we were going to keep the operations of our 500-member community running with a staff of seventy-five instead of 300.

Some of the employees lived in model rooms, some lived in rooms on air mattresses, and some people, like me, lived in our health center, with memory care and skilled nursing. I lived in a tent in the community hall.

We left our titles at the door and we all took on different roles, whatever we needed to do to take care of members. Everybody at mealtime became someone that delivered meals. Everyone became someone who would disinfect our common areas. Everyone became whatever we needed them to be in the moment. I don't even know that some of my employees that I was serving with knew I was the COO. They just knew I was that girl that came and made French toast on Sunday mornings and vacuumed the hallways and helped do laundry. It didn't matter because it was all of us together, fighting a common enemy called COVID.

Each day, I would crawl out of my tent, put on my scrubs and ball cap, and go down to see who needed help with breakfast. I might be feeding a member, I might be cooking in the kitchen, I might be just engaging with members around a game of cards or a board game, or painting nails or giving a haircut. By the time breakfast was over, it was already lunchtime, and we were making sure that everybody was eating and getting their meals. Days were filled with making sure our households were clean, members' rooms were clean, laundry was done for everyone, and everyone received their medications. And spending time together, like sitting outside in the courtyard, soaking up the sun, talking and visiting. We did things to keep people entertained, too, like Zoom karaoke. They got such a hoot out of hearing me sing not well.

We were working twelve, fourteen, sixteen hours a day, doing what was needed and trying to keep everyone's spirits up. It was constant motion. I will admit that sometimes it was nice to retreat to my tent and just turn off the device and just be. I have an Energizer Bunny in my body, so it wasn't so much physically exhausting as much as just mentally exhausting. Retreating to my tent and just being by myself was a relief for me.

Two weeks went by and the coronavirus was a hot-fire mess in Georgia. Then four weeks. I got everyone together and said, "If you need to go home, you can. You did what I asked you to do. You committed for four weeks. But I still need you." That's the hardest thing I've ever had to do as a leader, to say, "You have given me what you promised, but I need more." And every time I did that, they would say, "You can count on me." And that's not about me, it's about what we do here. It's about our mission of loving and serving members. We make a promise to them that they never have to leave, that we will move them through the continuum of care as they progress in age, and that we will always take care of them.

This was a wonderful example of seeing people living our mission in action. It was about living it to the extreme. And it was a beautiful thing. Our employees talk about our members as their second family. We got to live that; we got to see it in action.

Employees made a commitment to leave their own families during this crisis so they could take care of the members of their second family. We have one director of nursing who has six kids, a husband, and her mom who lives with them. She talked to her family, and she said, "I feel like I need to do this." And the family said, "Don't worry about us. You go and do this and we will take care of home." I've got a picture of her standing in a window, looking at her family two stories down, waving up at the window. That's powerful commitment.

Growing up, my father was a soldier who went to Vietnam twice. You know, I was watching my father go off and hoping he would come back. With COVID, we knew we could lose members. If we didn't do extreme things like locking in, we could lose members, and we weren't willing to do that. That's what I learned from my father about mission and commitment.

We locked in for seventy-five days. When we did leave, it was because we had the processes in place, the PPE and testing in place, that we needed to make sure we could take care of our members and employees. But it was so interesting on that last day when everyone was leaving, and their families were meeting them in the parking lot. They all hung out in the parking lot talking, like they didn't quite know how to leave. They were a big family of seventy-three sisters and two brothers, needing to leave each other so they could be with their own families.

I was remembering that the other day when we finally were able to open up to family visits for our members. They had not seen their families in person, to be able to touch and hug each other, for over a year. Our staff, because they remember how emotional they were after the seventy-five days, were standing by the doors, crying, while the families were reuniting in the rooms. They knew.

We all walked away changed. You can't go through something like that and not be changed.

Michael, Texas

Bar Owner—January 2021

Bars are places that people rely on in disasters. We're community hubs, a place where people go to be able to contextualize what's going on. So even people who you might not see in a bar regularly, you'll see them in times of crisis because it's a place to get news, it's a place to get out of your house, and it's a place to be around people in your neighborhood or community and reassure yourself that there's other people like you. That things are going to be okay. This particular disaster, though, was one that featured humans gathering as the disaster.

When we had to shut down, we wanted to find a way to be able to serve our clientele. We have a community of people that rely on us to be there for them for whatever reason they need us.

People don't go to bars because they want to get drunk. You can get drunk anywhere. People go to bars because of the basic human need to connect. Given the way modern society is going, there's more and more separation and less and less connection. As grocery stores have gone from local shops to big-box stores, there isn't anyone there to talk with anymore. Same with coffee shops. And now that everything is automated and delivered, you can sit in your home and order everything you need and have every interaction through a computer.

We were very cognizant of the fact that the people that needed us as bartenders were still going to need us, and probably more because they were stuck at home, so whatever drove them out of their house in the first place, that hadn't gone away. And more than that, their social outlet was gone; their community gathering outlet was gone.

We started livestreaming from the bar. We went on every night for an hour, and we did all kinds of crazy things, like we sang karaoke for them, hosted trivia nights, and sometimes made cocktails. I called it a virtual bar, and we were as interactive as possible with people. Sometimes we had guests come on from other places in the country. We ended up building a really, really strong following. Basically, virtual bar clientele would sit at home and have a beer, or they'd have a drink of their own, and they would come and talk to us and they would watch us do silly stuff. We put out a tip jar that they could put money in for the staff. It was surprisingly powerful.

That lasted for a while until Texas reopened again, very early and very unwisely. At the time, we were getting towards the end of whatever resources we had, so we tried to open as safely as possible. That lasted for a couple of weeks until one of my bartenders got COVID. Then I was furious. Furious that we'd been put in the position of even trying to let people in our place. And so, out of pique, I recorded a video that was basically addressed to Greg Abbott, the governor of Texas. It was a plea from a bar in a pandemic. It ended up getting something like half a million views on social media. What a lot of people didn't realize was that bars were excluded from a lot of the aid being offered to small businesses during the pandemic. We were placed in a position of needing to open as soon as we were allowed to, even if it was unwise.

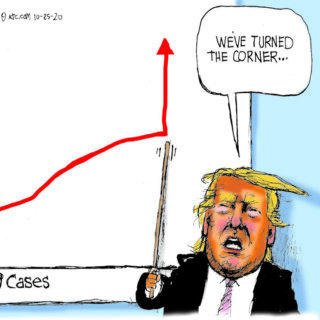

Pretty much right after my video, Texas closed down again because there was a big spike in cases. It was a big spike at the time, but compared to where we are now, it was nothing. That big spike that closed Texas down in July was a fraction of where we are now.

Mike, Florida

Doctor—January 2021

We have knowledge we learned based on our experiences in past pandemics. Yet, over the last year, we've acted like we learned nothing. That's very disheartening. We have had a lack of direction, and that's been very frustrating. They say that tough times bring out the best in people. It also brings out the worst in people. I have seen benevolence and kindness that was just phenomenal. And I have seen selfishness and self-centeredness that I would never have expected. It's really been an eye-opening experience.

My grandmother used to say, "I've been alive long enough that I have a right to say what I believe, especially if it's true." I'm not even close to her age, but that being said, I also feel that I've been around long enough, and especially around the medical field long enough, more than thirty-five years, that I can be open and honest.

Over the last year, I've become extremely disappointed with people, from leadership all the way down. I've seen political leaders come out and say, "The doctors and the medical experts say this, but I'm going to do what I want to do." And they're supposed to be our leaders. When people say, "I'm not going to follow guidelines because it's an infringement on my rights," I want to ask, "At what point does it become not all about you but all about everybody else and all about society?" Rather than people uniting with a focused approach, which would have led to a lot less suffering and death for many people, many leaders took such a selfish and self-centered approach that it made a bad situation terrible.

And I'll be honest, I would never have foreseen this happening. Previously, I thought that if we had a worldwide pandemic and we knew it and we saw it daily, that we would take the right approach, follow the high road, a consistent approach. We have done none of that.

I work as a hospitalist and do critical care medicine as well as palliative care work. In the Florida panhandle, our COVID hospitalization numbers have been climbing rapidly. From the beginning in March through November, I would have twelve to fifteen patients to work with each shift, with somewhere between two to four COVID patients. Occasionally, I had up to eighteen patients, but that would be a heavy load. On my shift a week and a half ago, I had twenty-six patients, fourteen of which had COVID. COVID-positive patients take about 50 percent more time. So taking care of twenty-six patients was actually like taking care of thirty-nine regular patients. Four of those patients were in the ICU on mechanical ventilators, which takes even more time.

I truly try to provide the best care I can for each patient, but at some point, it's like something's got to give. That is very disheartening to the doctors and nurses and other members of the medical team because we try to give our all, but unfortunately, it doesn't always work. I've taken care of hundreds of patients with this disease, and I've seen dozens and dozens die from it. Yesterday, more than 4,000 people died from COVID nationally. Many of those dying are young, and even more are dying alone.

It's frustrating when the emergency room is packed with COVID patients, the ambulance bays are packed with COVID patients, and we have no ICU beds available for our critically ill patients. I had a patient come in who was not COVID positive, but he was bleeding out from the bottom, terribly, and he had dropped his blood count by two-thirds.

When a COVID patient died, we cleaned the room and then put this guy in there, but he was the only non-COVID patient in the entire ICU. We have other patients coming in who need ICU beds, like patients with acute strokes and severe heart failure. When these patients come in and the hospital tells them, "We don't have any beds, you've got to go to another hospital," that means more time before they're admitted. As they say, every second is brain tissue in a stroke; every second is heart muscle in a heart attack. And we're having to divert these patients because there's no room. And if we can fit them in the hospital but not in the ICU, then they are put on other floors without the equipment and staffing needed to give them the proper care.

I started during the HIV days, so I've been doing this a long time. Now, when I get home after working up to sixteen hours instead of what is supposed to be a twelve-hour shift, I just try to close my eyes, sleep, and let it go. Because I know that I have to go back tomorrow and do it again.

About the Author

Michelle Fishburne is a full-time digital nomad, splitting her time between her 2006 motorhome, Airbnbs, and the occasional housesitting gig.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy.

Beginning in 2022, the series expands to include 1000-word blog posts, as well as longer commentaries, essays, articles and media productions that address the public health and political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic from multiple perspectives. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Recommended Resources

Text

Duffy, Mignon, Amy Armenia, and Kim Price-Glynn, eds. From Crisis to Catastrophe: Care, COVID, and Pathways to Change. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2023.

Fishburne, Michelle. Who We Are Now Stories of What Americans Lost and Found during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023.

Kim, Lisa, Rowena Leary, and Kathryn Asbury. "Teachers’ Narratives During COVID-19 Partial School Reopenings: An Exploratory Study." Educational Research 63, no. 2 (2021): 244–260.

Zhao, Xiang. "Experiencing the Pandemic: Narrative Reflection about Two Coronavirus Outbreaks." Health Communication 36, no. 14 (2021): 1852–1855.

Web

Barry, Ellen. “She Was More Than a Statistic in a Pandemic: ‘We Didn’t Want Her to Get Lost.’” New York Times. March 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/22/us/coronavirus-deaths-united-states.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article.

“COVID-19 and MIS-C: Morgan’s Story.” Johns Hopkins Medicine. November 29, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid-19-and-mis-c-morgan-story.

Di Gennaro, Francesco, Damiano Pizzol, Claudia Marotta, Mario Antunes, Vincenzo Racalbuto, Nicola Veronese, and Lee Smith. "Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) Current Status and Future Perspectives: A Narrative Review." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 8 (2020): 2690.

Fishburne, Michelle. “Who We Are Now: Our Stories.” Who We Are Now. https://www.whowearenow.us/real-american-stories.

"Innovative Uses of Storytelling During the COVID-19 Pandemic." ArcGIS StoryMaps Collection. Accessed on August 11, 2023. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/edf692e68f414ffea5d87ad36f94f9df?item=1.