Overview

Former Centers for Disease Control branch chief, Daniel Pollock, reflects on the CDC's failure in preparing for and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. A call to action, Pollock suggests a renewed institutional commitment to learning and transparency for the sake of public health and safety.

Commentary

Multiple COVID-19 waves have left in their wake compelling evidence of long overlooked gaps in pandemic readiness and responsiveness. The primary lesson for the US public health and healthcare sectors is that this deep-rooted ignorance took a huge toll on their ability to contend with a novel, rapidly spreading, and lethal contagion. As historian Peter Burke recently noted: "Many vivid examples of the consequences of ignorance come from the history of diseases."1Peter Burke, Ignorance: A Global History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 189. COVID-19 is a current case in point. What was missed or mismanaged in the run up to the pandemic and during its catastrophic course will, if left unexamined and uncorrected, lead to enormous suffering and loss in additional public health crises. In this commentary, I want to elaborate on how institutionalized ignorance affected the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) response and what can and should be done to learn from the agency's mistakes, with the goal of avoiding a repetition.

A thorough and fully transparent probe of CDC's recent history is warranted, one that scrutinizes "institutional obliviousness, under a succession of agency directors and programmatic leaders, to basic gaps in readiness and responsiveness that became glaringly obvious during the pandemic and contributed to numerous missteps in the US response to COVID-19."2Daniel Pollock, "COVID-19 Lessons in Ignorance," Southern Spaces, April 28, 2022, the first in a public health series covering the pandemic: https://southernspaces.org/2022/covid-19-lessons-ignorance/. Far too much had to be cobbled together on the fly in early 2020 largely because of prior organizational neglect. And far too little has changed three years later, even as CDC moves ahead with its latest—to date, largely upper echelon—reorganization.3Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "CDC Moving Forward Reorganization: A Notice by the Center for Disease Control," Federal Register 88, no. 29 (2023): 9290, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/02/13/2023-02929/cdc-moving-forward-reorganization.

Yes, SARS CoV-2 is a novel pathogen that spread rapidly, wreaked extraordinary devastation, and evolved quickly. Lots of impromptu learning about the virus and measures to contain or counter was necessary. However, pandemic warning signals abounded for years, and many assets CDC needed to function optimally in public health emergencies—as well as in non-pandemic times—were long overlooked or chronically under supported by virtue of the agency's own strategic planning, programmatic priority setting, and discretionary funding decisions. In surveillance and data science, for example, CDC did not fully mind and mend critically important gaps in electronic case reporting, immunization information systems, forecasting and outbreak analytics, and tools and dashboards for data visualization.

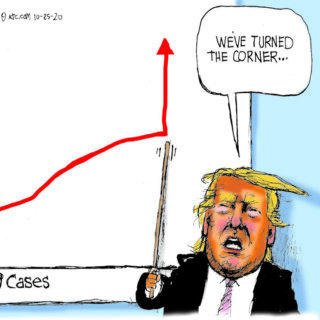

Certainly, factors largely beyond CDC's control had major impacts on the agency's performance. Besides the virus itself, CDC had to contend with (1) a coterie of federal government executives, most notably the 45th President, who failed to respond effectively and exerted unprecedented political interference; (2) a legacy of outbreak responses in the United States that are highly decentralized and contingent on a variety of situational circumstances; (3) longstanding constraints on CDC's public health authorities; and (4) chronic underfunding of public health programs at all levels of government. Each of these factors helps explain limitations, gaps, and shortcomings in the agency's performance. However, to leave the matter there would mean overlooking the impact of internal organizational factors that remain largely under CDC's control. Whether the agency has fully reckoned and responded to its internal problems is an open question that warrants much more attention.

"To be frank, we are responsible for some pretty dramatic, pretty public mistakes, from testing to data to communications," CDC Director Rochelle Walensky acknowledged in August 2022. However, the full CDC Scientific and Programmatic Review report that prompted Dr. Walensky's critique remains under wraps and not publicly available. Many months after the report was completed, all that CDC has published is a high-level summary and set of recommendations.4"CDC Moving Forward Summary Report," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Last reviewed September 1, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/cdc-moving-forward-summary-report.html. What was covered in the review, its methods and findings, and how conclusions were reached are shrouded in secrecy. Sequestering the report does not bode well for efforts to learn from CDC's COVID-19 experience and improve the agency's performance. Instead, CDC leaders have opted for a form of knowledge concealment that serves to perpetuate institutionalized ignorance.

For those of us who are deeply concerned about where the agency is headed, this is a fraught moment, yet organizational dysfunctions, mishaps, setbacks, and downturns are not necessarily points of no return. Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic and CDC's response to it can lead to changes that help revitalize the agency. Concealing the recent scientific and programmatic review report is not a good start along the path of organizational learning.

"Organizational learning," according to a leading researcher in the field and her colleagues, "is a process through which experience performing a task is converted into knowledge, which, in turn, changes the organization and affects its future performance."5Linda Argote, Sunkee Lee, and Jisoo Park, "Organizational Learning Processes and Outcomes: Major Findings and Future Research Directions," Management Science 67, no. 9 (2021): 5399–5429. The process should include gathering and moving information across organizational boundaries; eliciting and using multiple viewpoints; acknowledging hierarchies, policies, and practices that have not worked; and trying new approaches that have a higher likelihood of success. A prime example of an opportunity to learn from the COVID-19 experience is reckoning with how the agency organized, staffed, and operated its emergency response. From my perspective, the structure and process defects were profound and persistent, with the upshot that returns on the extraordinary time and effort so many CDC responders committed to their tasks fell well short of what would warrant use of all those precious resources. What purposes did the CDC response serve? Did the agency achieve those purposes? What was necessary to get the job done? Among the more specific questions about CDC's emergency operations is whether all the work involved with preparing, clearing, and presenting extensive PowerPoint slide decks in daily COVID-19 briefings was worthwhile. What were the benefits and at what cost?

Most of CDC's performance problems during the pandemic were the legacy of organizational neglect, not the exigencies of a novel corona virus or other external factors. The botched laboratory test rollout, flawed testing guidance, poorly prepared public health guidelines, confusing messaging, misguided mask recommendations, multiple data and analytic deficiencies, staffing shortfalls, and publication delays are traceable to assumptions widely held within the agency about institutional readiness coupled with longstanding inattentiveness by CDC directors and programmatic leaders to known or partially understood gaps. That CDC was not ready to go live sooner with a publicly facing, state-of-the art COVID-19 data display epitomizes what the agency had neglected. Instead, other data visualization websites, most notably Johns Hopkins University's dashboard, served as the go-to destinations for pandemic surveillance data. The reputational damage to CDC is severe and could have been avoided.

So much had to be launched or improvised by CDC in crisis mode because so much had been taken for granted or ignored for such a long time. Some additional examples from my own experience: When I joined the CDC response as Deputy Incident Manager for data and surveillance at the end of March 2020, I was surprised to learn that the agency had yet to introduce a process to enable secure data access and distribution of COVID-19 data sets to prospective data users who had been identity-proofed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Further, CDC had taken no steps to inventory and document relevant data sets and make provisions for sharing de-identified data with news organizations, one of which moved forward with a lawsuit to gain access to COVID-19 case data aggregated by CDC. The agency should have closed these basic gaps in data provisioning well before the pandemic, not during the throes of it. The only explanation of this blunder that I can think of is lack of forethought and follow through.

SARS CoV-2 is not the first viral respiratory pathogen to emerge and spread across country borders in the twenty-first century. While each international outbreak has presented a unique mixture of causes and consequences, they also have had much in common. That commonality places a premium on learning from each event and applying take-away lessons in a thoroughgoing way. What's ahead epidemiologically can surpass what's happened already in terms of complexity and magnitude, and that only heightens the stakes for CDC's organizational learning and pandemic preparedness.

While there are many pockets of CDC excellence, the organization, most notably because of its COVID-19 response, has taken multiple hits—some reflect ignorance about the agency's mission, operations, opportunities, and constraints but others are knowledgeable, on target, and of high consequence. There is much to do—and soon. We need to know more about CDC's performance gaps and shortcomings, and how to remedy them. To that end, instead of treating the full details of CDC's COVID-19 mistakes as a sequestered resource, it behooves CDC leaders to build on, transfer, and most importantly, act on what has been learned.6Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert I. Sutton, The Knowing-doing Gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge into Action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2000): 261. In the pandemic's wake, a much stronger commitment to organizational learning by CDC will provide the quickest and most effective solutions to the institutionalized ignorance that placed the public and the agency at risk.

About the Author

After completing the CDC's Epidemic Intelligence Service training program in 1986, Daniel Pollock worked as a medical epidemiologist at the agency for 35 years. Dr. Pollock led the CDC unit responsible for national surveillance of healthcare-associated infections from 2004–2021, and he served in CDC's COVID-19 emergency response in the spring of 2020 as the Deputy Incident Manager for data and surveillance.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy.

Beginning in 2022, the series expands to include 1000-word blog posts, as well as longer commentaries, essays, articles and media productions that address the public health and political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic from multiple perspectives. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Recommended Resources

Text

Argote, Linda. Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining, and Transferring Knowledge. 2nd ed. New York: Springer, 2013.

Cannon, Mark D., and Amy C. Edmondson. "Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently): How Great Organizations Put Failure to Work to Innovate and Improve." Long Range Planning 38, no. 3 (2005): 299–319.

Lee, Michael Y. and Amy C. Edmondson. "Self-managing Organizations: Exploring the Limits of Less-hierarchical Organizing," Research in Organizational Behavior 37, (2017): 35–58.

von Lubitz, Dag K.J.E, and Candace J. Gibson. The Nature of Pandemics. London: Routledge, (2023).

Roberts, Joanne. "Organizational ignorance," in Routledge International Handbook of Ignorance Studies. Edited by Matthias Gross and Linsey McGooey. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, (2022): 367–376.

Roux-Dufort, Christophe. "The Devil Lies in Details! How Crises Build up Within Organizations." Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 17, no. 1 (2009): 4–11.

Whitford, Andrew B. Herding Scientists: A Story of Failed Reform at the CDC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Web

Carlisle, Lois. "For the Health of the Nation: A History of the CDC in Atlanta." Atlanta History Center. May 7, 2020. https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/blog/a-history-of-the-cdc-in-atlanta/.

Council on Foreign Relations. "Improving Pandemic Preparedness: Lessons from COVID-19." Independent Task Force Report no. 78. (October 2020). https://www.cfr.org/report/pandemic-preparedness-lessons-covid-19.

Jalonen, Harri. "Ignorance in Organizations—A Systematic Literature Review." Management Review Quarterly. (January 2023). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11301-023-00321-z.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Peter Burke, Ignorance: A Global History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 189. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Daniel Pollock, "COVID-19 Lessons in Ignorance," Southern Spaces, April 28, 2022, the first in a public health series covering the pandemic: https://southernspaces.org/2022/covid-19-lessons-ignorance/. |

| 3. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "CDC Moving Forward Reorganization: A Notice by the Center for Disease Control," Federal Register 88, no. 29 (2023): 9290, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/02/13/2023-02929/cdc-moving-forward-reorganization. |

| 4. | "CDC Moving Forward Summary Report," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Last reviewed September 1, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/cdc-moving-forward-summary-report.html. |

| 5. | Linda Argote, Sunkee Lee, and Jisoo Park, "Organizational Learning Processes and Outcomes: Major Findings and Future Research Directions," Management Science 67, no. 9 (2021): 5399–5429. |

| 6. | Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert I. Sutton, The Knowing-doing Gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge into Action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2000): 261. |