Overview

Stephanie Rountree examines the relational possibilities of queer performance in Max Vernon's The View UpStairs, a play that dramatizes the 1973 Up Stairs Lounge fire in New Orleans. Rountree contextualizes the fire within the scope of the twentieth century gay liberation movement and explores how the play's various production sites both embody and transcend the time and place of the tragedy.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

I. Introduction

In February 2017, playwright and composer Max Vernon debuted their first Off-Broadway musical The View UpStairs at the Lynn Redgrave Theater in New York City. Following The View's success with another hit musical later that same year, which sold out theaters and nabbed a stack of awards, Vernon firmly established their reputation as a "radical" creative mind known for "gigantic" productions in immersive staging that render an "unexpected and marvelous" audience experience.1Excerpts taken from the following reviews found on Max Vernon's website: Lina Landstroem, "Queer History on Stage: A Review of The View UpStairs by Max Vernon," Public Seminar, March 1, 2017, https://publicseminar.org/2017/03/when-a-bar-was-your-home/; Zackary Stewart, "KPOP," TheaterMania, September 22, 2017, https://www.theatermania.com/off-broadway/reviews/kpop_82533.html; Elisabeth Vincentelli, "Review: A Gay Nightclub Tragedy, Decades Before Orlando, in 'The View UpStairs'," The New York Times, March 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/07/theater/the-view-upstairs-review.html. The View UpStairs animates the real life Up Stairs Lounge gay bar environment on the eve of an arson attack on June 24, 1973. The tragedy stands as the deadliest fire on record in New Orleans history, and it once figured as the deadliest US attack on LGBTQ+ people until Orlando's Pulse Nightclub massacre in 2016. Considering the production's immersive staging and use of melodramatic mode, I interpret The View UpStairs as an adaptation in a genealogy of liberatory queer performance tracing back through the "drag reviews" and "deeply interactive, cross-dressing . . . nellydramas" staged at the Lounge in the 1970s.2Robert W. Fieseler, Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2018), 227. The View activates a legacy of intersectional coalition that is vital to contemporary social justice activism confronting the racist, nationalist, and anti-LGBTQ+ violence emboldened in a post-Trump America. The View builds new forms of solidarity across impossible limits of time, place, and subjectivity by dissolving distinctions between 2017 and 1973, New York and New Orleans, actors and audience.

II. The Up Stairs Lounge, 1970–1973

As a Los Angeles native and NYU alum, Vernon was drawn to the Up Stairs Lounge fire not so much for its tragedy but because the "fire [had] been erased" from history.3Max Vernon, interview by author, September 8, 2017. Robert W. Fieseler underscores in Tinderbox (2018) that "more stories about the Up Stairs Lounge appeared in major news outlets after the [2016] Pulse shooting than in the previous four decades."4Fieseler, Tinderbox, xix. While Vernon was understandably shocked by the tragedy's erasure, the complexities surrounding the arson, its immediate but mostly local news coverage, and its swift muting from public discourse resist hasty conclusions about the cause or consequence of such silence. On the one hand, the contemporaneous frontpage spread in the Times-Picayune had broken a multigenerational "social compact" whereby New Orleans dominant society had tolerated queer society as long as it remained apolitical and out of sight.5See the front page spread of The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), June 25, 1973, Monday Morning Edition, 1. The Up Stairs Lounge arson and media coverage acknowledged a thriving gay culture within the French Quarter. The arson's silencing became a tragedy suppressed from public consciousness. Media coverage also non-consensually "outed" many closeted survivors for whom employment, housing, and other basic needs depended upon privacy. For them, media silence was more than a welcome salve; it was necessary for survival. This ethical complexity between historical recovery work and guarding survivors' privacy presented a daunting challenge: How to restore cultural visibility when so many victims and survivors would not have wanted public exposure, whose agency to "come out" (or not) was taken from them? This exigency guided Vernon's creative work. It underscores why this musical is decidedly not about the arson but, rather, a dramatic "View" of life from the perspective of "composite" characters adapted from Up Stairs patrons, anonymously recovering the kinds of human connections that the bar made possible before and until June 24, 1973, at 7:53 p.m. when "[f]lames gathered on a front step."6Vernon, interview by author; Fieseler, Tinderbox, 70.

Aside from some library microfiche newspapers and a few Times-Picayune articles online, Vernon primarily referenced Clayton Delery-Edwards's 2014 book The Up Stairs Lounge Arson. Few other resources existed while Vernon was writing.7Clayton Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-Two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014); Vernon, interview by author; see also Johnny Townsend, Let the Faggots Burn: The UpStairs Lounge Fire (Bangor, ME: BookLocker, 2011). Townsend's 1989–90 archival work informed Delery-Edwards's research. Delery-Edwards, a native of New Orleans, was drawn to the fire when he "watch[ed] news coverage in 1973."8Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 2. His book was only the second book about the tragedy after Johnny Townsend's self-published and poorly documented interviews in Let the Faggots Burn (2011).9Townsend, Let the Faggots Burn, vii. Delery-Edwards's work was the clear, better choice for Vernon's research.10It is important to note that some inconsistencies exist in Delery-Edwards's text, as well. Today, Robert W. Fieseler's Tinderbox (2018) is considered a more thorough, accurate record of the fire.

The title of Delery-Edwards's first chapter, "Beer, Prayer and Nellydrama," scans as an early outline for the plot of The View. Delery-Edwards describes the Lounge as a cultural space that sought to insulate patrons from homophobic violence, what Vernon would imagine in a musical number, "The World Outside These Walls."11Max Vernon, The View UpStairs (New York: Samuel French, 2017), 45. The Up Stairs Lounge operated amid tumultuous years (1970–1973) of gender politics: "Roe v. Wade, the Women's Liberation movement, [and] the Gay Liberation movement spurred by the 1969 Stonewall Riots" and its one-year anniversary parade.12Vernon, The View UpStairs, 45. Police brutality and institutional violence compelled LGBTQ+ people to remain closeted for survival, though Delery-Edwards explains that some sought escape via "life in a big city . . . Someplace like San Francisco. Or New York. Or New Orleans."13Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 10. However, these urban spaces and the gay bars they provided were not reliably safe. "Police would raid gay bars for no real cause," he writes, "beating up the patrons without fear of repercussion, and arresting people for infractions not much more serious than shaking hands."14Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 10. It was this kind of police raid that precipitated the New York City Stonewall Uprising in the early morning of June 28, 1969, when LGBTQ+ people—particularly those who were Black and Brown—fought back.15Although the most well-known, the Stonewall Uprising was not the first instance of LGBTQ+ resistance. The Cooper Do-Nuts Riot (1959) as well as the Compton's Cafeteria Riot (1966), both in California, precede Stonewall. Many have argued that Stonewall became central to the development of Gay Liberation largely as a result of practices of memory (organized activism) that arose to commemorate the event, such as the Christopher Street Liberation Day (1970), often cited as the first gay pride event in the country.

By 1973, the Gay Liberation movement that had been radicalizing in localized spaces before Stonewall was now galvanizing on a national scale, yet political activism still had not animated New Orleans. Ironically, the city's (and specifically the French Quarter's) deep history as a site of celebrated deviance may have delayed political radicalization.16Ryan Prechter, "Gay New Orleans: A History" (PhD diss, Georgia State University, 2017), https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/60/. Fifteen years before the Up Stairs arson, two significant events in New Orleans gay history occurred within seven months of one another, and their ambiguous correlation underscores gay New Orleans apolitical climate at the time. In 1958, the first gay Mardi Gras krewe—"the Krewe of Yuga"—was formed, and later that year, three white Tulane students murdered Fernando Rios, a gay Mexican man, in what would now be called a homophobic hate crime.17The three white Tulane murderers intended to "roll a queer," or assault a gay person, the night they killed Rios. Trial testimony revealed that the murderers bragged about the assault after they left Rios for dead. Clayton Delery-Edwards, Out for Queer Blood: The Murder of Fernando Rios and the Failure of New Orleans Justice (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 97. The murderers confessed to the crime but were acquitted. Meanwhile, New Orleans gay society continued to grow and thrive apolitically via the privacy of burgeoning gay Mardi Gras organizations. According to Delery-Edwards, gay society's response to Rios's murder was perhaps only recognizable in social migration toward newly founded gay krewes: "[Rios's] death and the fear it engendered motivated some gay men to join these fledgling organizations."18Delery-Edwards, Out for Queer Blood, 148. The city's cultural climate—Mardi Gras, gay krewes, cross-racial musical and cultural engagement, sex work, bohemian artistry, jazz, and substance-infused revelry—made the Quarter a mecca for gendered and sexual play, so long as participants abided by the social compact of apolitical invisibility and navigated onerous and Janus-faced local mores (e.g., public cross-dressing was allowed, but only on Mardi Gras).19James Karst, "Halloween Cross-Dress Costumes Lead to 21 Arrests in 1952: Our Times," The Times-Picayune, October 18, 2015, https://www.nola.com/news/crime_police/article_4522e6d7-b6bb-5143-a772-ee5712675293.html. LBGTQ+ people could enjoy a fragile sense of stability in the semi-closeted niche of the Quarter's gay bars. This local culture blunted the sense of urgency of a national "Stonewall moment," even after the tragedy at the Up Stairs Lounge.

Tucked away from Bourbon Street, just around the corner at Iberville and Chartres, the Up Stairs Lounge provided its patrons with social engagement, Christian community, and queer performance theater. The Lounge's "out-of-the-way location meant that you had to have a definite reason to go there," explains Delery-Edwards, while a continual schedule of events such as "costume parties, tricycle races . . . and the weekly Beer Bust" kept patrons returning for alcohol, comradery, and escapism.20Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. Up Stairs became a hub for the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), a Los Angeles based Protestant LGBTQ+ congregation that was founded and led by the openly gay Reverend Troy Perry.21Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 21. In spring 1971, Reverend David Solomon established the New Orleans branch, and by fall, MCC services were relocated to the Lounge.22Fieseler, Tinderbox, 25, 31–32. Over the year that the Lounge hosted MCC services, congregants became accustomed to continuing "fellowship" at the bar's "Sunday Beer Bust," so much so that even after the MCC moved to another location in 1972, "the congregation kept close ties with the Up Stairs Lounge and maintained the tradition of fellowship."23Fieseler, Tinderbox, 34. The Lounge owners, concludes Delery-Edwards, "had been very successful at creating a warm, welcoming environment."24Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29.

Early on, a few Up Stairs regulars built a stage and began to perform "light-hearted melodramas," often casting men as women characters, stylistically to "make the plays funnier" and practically "because the Up Stairs regulars included far more men than women."25Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 24–25. Given the plays' gender parody and over-acted pathos, the Up Stairs patrons "stopped calling these plays melodramas and started calling them 'nellydramas.'"26Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 25. Several of these productions were written and directed by Bettye McAnear, and "the Up Stairs Players were known to veer from her script in repeat performances by letting audience members interrupt the action to shout the big lines. In response, casts started ad-libbing to throw off the crowd."27Fieseler, Tinderbox, 33. These highly interactive, gender-playful nellydramas animated the Lounge stage for nearly all of its three years, a fitting performance genre for a gay bar given how melodrama, as Jonathan Goldberg argues, can "work . . . the system against itself, exposing how opposition is possible without imagining the reform of institutions that seem to be impediments to human flourishing."28Jonathan Goldberg, Melodrama: An Aesthetics of Impossibility (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 160. Up Stairs patrons and performers would have faced hostility beyond the walls of the bar, but in performing nellydramas, they created oppositional space, even without the capacity to affect systemic change. Plus, they were a lot of fun. Nellydramas were so beloved in the gay Quarter that even after the fire, the performances returned.29Fieseler, Tinderbox, 227.

Although the Lounge celebrated the nellydramas' gay parody, the Lounge owner initially "discouraged drag queens from coming into the bar," perhaps indicating the era's still-nascent articulation of minority gender identities.30Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. The art of drag reviews in the 1970s took gender performance much more seriously than mere gender parody; a drag queen's success was often evaluated by her "performative act of passing" as convincingly feminine.31Bryant Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again (Or Queer Theory as Drag Performance)," Journal of Homosexuality 45, no. 2–4 (2003): 351. Acceptance of drag performance was mixed, even among gay communities that had already radicalized politically. Betty Luther Hillman notes of San Francisco's Gay Liberation Movement: "While some liberationists appropriated drag as a symbolic statement against gender norms, others saw drag as exacerbating stereotypes of 'effeminate' homosexuality. Still others aligned with radical feminists who saw female impersonation and drag as an affront to women . . . These debates coalesced into contradictory stances on the political and cultural meanings of drag and drag queens as constituents of gay liberation."32Betty Luther Hillman, "'The most profoundly revolutionary act a homosexual can engage in': Drag and the Politics of Gender Presentation in the San Francisco Gay Liberation Movement, 1964–1972," Journal of the History of Sexuality 20, no. 1 (2011): 158.

When the Up Stairs Lounge welcomed Marcy Marcell (née Marco Sperandeo) as its first drag queen in 1972, it could be argued that the bar was making a bold statement about inclusion in their social community. Or, given that she "was a smash" right from the start, the decision may have just been about boosting beer sales.33Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. Regardless, Marcy "was soon a regular performer . . . her shows took place on Sunday evenings at eight."34Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. The Lounge owner eventually embraced these delightfully subversive "drag reviews," recommencing them at the bar he established after the Up Stairs Lounge burned.35Fieseler, Tinderbox, 227. On the night of the fire, Marcy was scheduled for her regular Sunday performance, but she procrastinated at home, feeling a premonition. She was watching a "Bette Davis movie" when reports of the fire appeared on television.36Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 50 (ellipses original); See also Townsend, Let the Faggots Burn, 184–185.

Shortly after the Sunday evening Beer Bust on Sunday, June 24, 1973, the patrons inside the Up Stairs Lounge heard the buzzer ringing from the front door of the bar. When a "patron [and] MCC congregant" opened a door to descend the staircase, fire exploded in a backdraft through the stairwell, clawing into the bar.37Fieseler, Tinderbox, 71. In minutes, the fire ripped through the Up Stairs Lounge as patrons and employees attempted to flee for exits in a building that failed to meet New Orleans fire codes.38Fieseler, Tinderbox, 183. When the pandemonium was over, thirty-two victims had perished, either immediately or in the following days as a result of injuries.39Fieseler, Tinderbox, 187. After the fire department turned off their hoses and first responders began sorting through the rubble, rumors arose that a drunken gay patron named Roger Dale Nunez had initiated a fight, been kicked out of the bar, and threatened on his way out "to burn this place to the ground."40Fieseler, Tinderbox, 66.

When historians consider why the Up Stairs fire did not stir pro-gay radicalization in New Orleans, Nunez's identity as a gay man frequently comes up: he was part of the LGBTQ+ patronage, not a hostile anti-gay assailant. But there are other, more systemic factors that played into the arson's erasure from public discourse and memory: mishandlings by police forensics, a foiled criminal investigation, political urgency to diminish public attention to a gay bar, homophobic misrepresentation by local media, and outright public contempt for the victims' sexuality. By August 1973, Nunez had evaded arrest by an apathetic police force. Some parents and families of victims had refused to claim the bodies of their dead sons and brothers. To this day, the bodies of four victims—three unidentified victims and one military veteran—lie in a "city-affiliated cemetery for indigents."41Fieseler, Tinderbox, 191. No protestors stormed City Hall. Few challenged the homophobic culture or city codes. The Up Stairs Lounge arson would not galvanize enduring change or create the organized, "sustained gay activism" that Stonewall's one-year anniversary had inspired nationally.42Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 164. The Up Stairs Lounge would not become a "Southern Stonewall."43Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 164.

However, the fire was not altogether ignored. For a small network of LGBTQ+ individuals aware of the Lounge through the MCC, the tragedy compelled support from beyond New Orleans. Both Delery-Edwards's and Fieseler's books document the days after the fire when nonlocal, gay activists arrived in New Orleans, including Los Angeles leaders Troy Perry (MCC founder) and Morris Kight (President of Gay Community Services Center of Los Angeles).44Fieseler, Tinderbox, 111–112. Perry, Kight, and others came to help local survivors and rouse LGBTQ+ support, but people in New Orleans, especially survivors of the fire, were largely resistant to what they perceived as outside meddling by "fairy carpetbaggers."45Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 63, 146–149. This name-calling queered the Reconstruction-era slur created by unreconstructed white southerners for northerners who descended upon the defeated South supposedly for personal gain.46Delery-Edwards, 63, 146–149. Closeted gay New Orleanians who survived the Up Stairs fire only to be forcibly "outed" as gay in its aftermath desired a private space to heal. The Lounge owner was especially critical of Perry and Kight, suggesting that they were a "divisive force," and that "perhaps there [was] some correlation between the amount of gay activism in other cities and the degree of police harassment."47Fieseler, Tinderbox, 228. It was clear that many of the survivors of the fire were hostile toward these "fairy carpetbaggers."

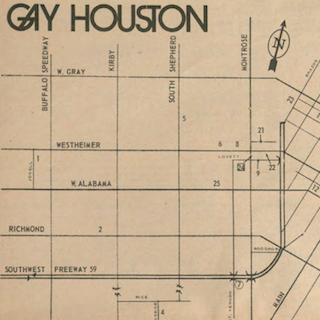

At the same time, it was the work of MCC members, the Gay Community Service Center of Los Angeles, and a wide range of LGBTQ+ activists and donors from beyond New Orleans who provided financial relief for survivors as well as families and loved ones of those who perished. In January 1974, Kight met with "concerned members of the New Orleans Community" and deployed the "National New Orleans Memorial Fund" to disperse $6,000 to support those impacted by the arson, an amount that would grow to "nearly $18,000."48Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 147. "[I]n some ways," writes Delery-Edwards, "the most important political activity connected to the fire wasn't local at all; it was a brief, national project intended to provide aid and support to survivors of the Up Stairs."49Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 146. Through their skills in fundraising and national outreach, the "fairy carpetbaggers" facilitated donations from "all over the country: New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Atlanta, Jacksonville, Detroit, Chicago, Houston, Phoenix, Denver, Boulder, San Jose, Los Angeles, and San Francisco."50Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 147.

New York, Boston, Baltimore, Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco: all of these US cities and six more have staged Max Vernon's The View UpStairs since its debut in 2017. Add to the list a 2018 production at the Hayes Theatre Company in Sydney, a 2019 run at the Soho Theatre in London, and an upcoming 2022 performance at Nippon Seinenkan Hall in Tokyo, and the impact of Vernon's musical underscores the representational power of this local New Orleans narrative for national and international audiences. The View UpStairs immerses its audience in an emotionally powerful depiction of that 1973 French Quarter blaze by engaging melodramatic modes of performance similar to the Lounge's nellydramas and drag shows. Vernon's musical adaptation makes room for relationality across generations and geographies of LGBTQ+ experience.

III: "Possibilities in the Impossible": Immersive Staging, Queer Melodrama, and Adaptation

In January 2017, friend and colleague Dr. Ryan Prechter emailed me an article previewing The View UpStairs. We were both incredulous and ecstatic: Ryan's doctoral research on the Up Stairs arson had appeared in his post-1900 history of gay New Orleans, but circa 2017, very few people in the general public had heard of the fire.51Ryan Prechter, "Gay New Orleans: A History." Googling for tickets, I saw our future. We would attend the production and try to meet the playwright: How did you learn about this occluded event in New Orleans gay history? Why tell the Up Stairs Lounge story now, after all these years? All of these events transpired, and while I was, and remain, awestruck to experience Vernon's production and professional generosity, I could not help but feel apprehensive, too. The scenario that led to the staging of The View UpStairs—whereby an Los Angeles-bred and New York City-based activist/writer imaginatively travels to New Orleans to adapt the closeted Up Stairs patrons into characters engaging a national gay rights discourse—felt eerily similar to the history of the arson's immediate aftermath. I also could not ignore that something about Vernon's production felt different from that history, unexpected.

Walking into the Lynn Redgrave Theater for the 8:00 p.m. performance of The View UpStairs on Saturday, March 27, 2017, Ryan and I pass through double French doors into what looks like a dingy cabaret with a beat-up piano, retro cigarette dispensers, dank velvet curtains, a dildo chandelier, and rafters strung with Mardi Gras beads.52The View UpStairs, written and composed by Max Vernon, dir. Scott Ebersold, chor. Al Blackstone, performed by Jeremy Pope, Taylor Frey, Frenchie Davis, Benjamin Howes, Michael Longoria, Ben Mayne, Randy Red, Nancy Ticotin, Richard E. Waits, and Nathan Lee Graham, New York, Lynn Redgrave Theater, March 25, 2017. Surrounding the cabaret seems to be a compact auditorium with riser seating on three sides. We enter, not into the lobby but, onto the stage, a disarming immersive design with dainty two-top tables and chairs. Some audience members are finding their reserved seats on the set. Ryan and I purchase drinks from the staged and operational Up Stairs bar and find our seats in the front row of the risers. We play Where's Waldo with the queer iconography around the room. Posters of Dolly Parton, Barbara Streisand, and David Bowie cover the walls. A nude Burt Reynolds lounges above velvet curtains. Ryan explains that in a well-known photograph of Up Stairs Lounge's bartender-manager, the same poster adorned the bar wall in 1973.53Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 20. Our game continues until an attractive blonde man in a mesh shirt and retro-coiffed moustache slides next to my colleague and starts chatting him up: "I've never seen you here before. Are you new?" When the play begins, we recognize him as the Dale character (Ben Mayne)—a nod to the historic arson suspect Roger Dale Nunez.

This intimate dissolution of the fourth wall pulls the audience into a participatory experience that clearly embodies Josephine Machon's definition of "immersive theatre," as The View's production creates a conspicuous confluence of space and time disrupting passive reception, and compelling the audience to actively engage with our bizarre surroundings in a room that is simultaneously 1973 and 2017, stage and audience, New Orleans and New York.54Josephine Machon, Immersive Theatres: Intimacy and Immediacy in Contemporary Performance (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013); See especially "The Scale of Immersivity," 93–102. Vernon explains in their author's notes that the musical "was originally performed in an intimate, immersive setting, casting the audience as patrons in the bar when they walked into the theater. This allowed for actors to ad-lib with audiences in a way that was often hilarious, and also made the fire sequence more immediate and terrifying."55Vernon, The View UpStairs, 7. The act of casting audience members underscores "a pivotal criterion" of Machon's immersive theatre: "Where an event is wholly immersive the audience-immersant is always fundamentally complicit within the concept, content and form of the work. As a consequence, . . . the naming of 'the audience' as such becomes a vexed term in itself . . . the special and active exchange that occurs between the performance and the audience member[] illustrat[es] the breakdown of division between audience and creative crew."56Machon, Immersive Theatres, 98. The orientation of the audience's entrance onto the stage inaugurates their entry into a "contract for participation" in the audience-immersant role, whereby "the structures of the immersive world . . . invite varying levels of agency and participation."57Machon, Immersive Theatres, 99–100. The View's immersive staging compels the audience to assume a participatory role that recalls the The Up Stairs Players' highly-interactive nellydramas.

Vernon's immersive, interactive staging and the emotional intimacy it facilitates between audience-patrons and cast-patrons further reimagines the melodramatic genre of the original Up Stairs nellydramas. However, I interpret The View's use of melodrama not as genre but as mode in Linda Williams's definition; the "melodramatic mode" in theater is "a modality of narrative with a high quotient of pathos and action" deployed to render a moral conclusion.58Linda Williams, "Melodrama Revised," in Refiguring American Film Genres: History and Theory, ed. Nick Browne (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 51. This modality manifests in The View's immersive production and is compatible with Vernon's explicit script instructions that actors should perform their characters in controlled realism, eschewing hyperbolic "melodrama" in the colloquial sense.59Vernon cautions, "While it's important to carve out true emotional beats for the characters, never let the piece veer into melodrama." Vernon, The View UpStairs, 6. Realistic performance by cast-patrons staged in immersive proximity and engaged with audience-patrons produces affective attachment through the immediacy of narrative action, and Vernon most certainly leverages this mode to foster a moral conclusion, as I examine below. As the 1973 cast-patrons assemble on stage, piano man Buddy (Randy Redd) launches into the catchy opening number, and the band "rock[s] the f*ck out."60Vernon, The View UpStairs, 9–11. The lights drop, and enters the protagonist Wes (Jeremy Pope), a gay Black millennial fashion designer. In the present day, he buys the burnt-out former Up Stairs Lounge to launch the "flagship for [his] store."61The View UpStairs, 73; At the time of this publication, the former Up Stairs Lounge now houses office space and the kitchen for The Jimani sports bar.Lamenting the building's condition, especially the "ugly curtain" draped across the blackened windows, Wes "snorts . . . cocaine," inaugurating his drug-induced "trip" back to June 24, 1973.

Wes's future-past presence disrupts the Up Stairs patrons, and the ensuing commotion introduces Vernon's composite characters. The bartender-manager Henri (Frenchie Davis) slings drinks while Willie, played by the indomitable Nathan Lee Graham, struts around the bar stealing the stage, as a "flaming, demented former ballerina" is wont to do.62Vernon, The View UpStairs, 8, 5; Vernon, interview by author. MCC priest Richard (Benjamin Howes) leads a church service attended by all of the aforementioned characters and one "runaway hustler" named Patrick (Taylor Frey) who becomes Wes's love interest.63Vernon, The View UpStairs, 5; For a rich discussion of performance theater that stages LGBT+ engagement in religious liturgy, see Lusie Cuskey, "The Liturgy that Dare Not Speak Its Name: Religious Engagement and Affective Memory as a Site of Queer Activism in Musical Theatre," Ecumenica: Performance and Religion 13, no. 1 (2020): 52–68. Vernon's characters do indeed gesture toward real patrons who were at the bar on the night of the arson, but his adaptation precludes historical reenactment. "Many of these characters are composites of real people who frequented the UpStairs," Vernon writes in their script, "but out of respect and creative license I've changed names and certain details."64Vernon, The View UpStairs, 8; Vernon, interview by author. Adaptation helped Vernon navigate the ethical precarity of depicting people who were largely closeted at the time of the fire and who risked losing everything if outed in 1973 New Orleans.65Vernon explains, "And so, I think in many ways, where they have these anti-sodomy laws in the South, and where regularly, if a gay bar was raided and they took your ID, your name could be printed in the paper, and you could lose your job. You could lose housing. I think they didn't have the same freedoms as New York to be as visible, so they had a different mode of survival of how they had to exist in these spaces like the Up Stairs Lounge." Vernon, interview by author.

Adapting composite characters in melodramatic mode also facilitates The View's stance on intersectional coalition, which nods to the historic Lounge's rare, inclusive history as one of "a few fringe establishments [that were] brazen enough to encourage interracial mingling"; the bartender-manager "even let[] women into the bar at a time when gays and lesbians were strictly separated."66Robert W. Fieseler, "The UpStairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People. Its Legacy Still Haunts Black Gay New Orleans," The Daily Beast, May 13, 2019, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-upstairs-lounge-fire-killed-32-people-its-legacy-still-haunts-black-gay-ne. Gay communities are hardly immune to the racism and sexism that permeates dominant society. For example, in 1973, one of the oldest operating gay bars on Bourbon Street, Café Lafitte in Exile, "had a sign on the door . . . It said 'No Blacks, No Fems, No Women.'"67Fieseler, "The UpStairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People." However, the Up Stairs Lounge was different, and Vernon emphasizes the bar's unique inclusivity especially in their composite characters. For example, although the bartender-manager was historically a gay white man in "a gay white man's community," he "was known to be especially friendly to all comers," regardless of race or gender identity.68Regina Adams quoted in Fieseler, "The Up Stairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People." In this spirit, Vernon composes the bartender-manager character Henri, a "[t]ough as nails, no-nonsense, old-school butch lesbian" played in the original production by Grammy-nominated Frenchie Davis, a show-stopping Black woman singer, social activist, and educator.69Vernon, The View UpStairs, 7. While casting a Black performer in Davis was unique to this production, her "old-school butch lesbian" identity is proscribed, as is Willie's Black identity and Inez's and Freddy's Puerto Rican identities (characters who enter the plot later on).70Vernon, The View UpStairs, 5. While the Lounge's inclusivity was certainly progressive for its era, one cautions against overstating the diversity of its patronage, which was still largely white men even as Black, Latino/a/x, and women patrons were welcome. The Lounge owner's initial refusal to allow drag queens into the bar, for example, demonstrates the need for a nuanced understanding of the 1970s Up Stairs Lounge as a site of complex, overlapping, and sometimes contradictory social politics.

These historical complexities further contextualize Vernon's 2017 production, as they intentionally wrote and casted characters from underrepresented backgrounds to promote coalition across complex and intersecting subjectivities, even across distinctions between performer/audience. As José Esteban Muñoz explains, "performance permits the spectator, often a queer who has been locked out of the halls of representation or rendered a static character there, to imagine a world where queer lives, politics, and possibilities are representable in their complexity."71José Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 1. He further champions that "Queer performance . . . is about transformation, about the powerful and charged transformation of the world, about the world that is born through performance."72Muñoz, Disidentifications, xiv. For the cast- and audience-patrons of The View, the world born through performance creates possibilities for futures even freer than the noteworthy yet limited atmosphere of the 1973 Lounge. Vernon expresses this cautious ethos most clearly in the lyrics of the opening number "Some Kind of Paradise." The playwright explains, "It's not just 'Paradise!' . . . no matter what the time period, the world is always going to be kind of shitty and imperfect and evolving and in-process."73Vernon, interview by author. In fostering relationships across so many "evolving" and overlapping identities, generations, and performance subjectivities, Vernon challenges cast-patrons and audience-patrons together as actor-agents called to realize a more equitable future that was once im/possible in history and has evolved to remain differently im/possible in the present.

The View recasts the subjectivities of and relationships between the 1973 Lounge patrons and contemporary cast- and audience-patrons. Confronting the limits of these impossibilities through melodramatic mode and immersive theatre facilitates new possibilities. "The formal use of melodrama," Goldberg explains, "brings to a point of crisis the ideologies of gender and sexuality."74Goldberg, Melodrama, 21. Escalating these "ideologies" to their dramatic limits, the intense pathos can foster transformation by "imitat[ing] ways past the impasses of the impossible gender/political situation; it discovers new possibilities of relationality": "The indeterminations of the remediated nature of melodrama allow for the possibilities in the impossible."75Goldberg, Melodrama, 156. Indeed, Vernon's goal in writing and composing The View was to "imitate a way past the impasses" that have foreclosed millennial LGBTQ+ access to the experience and wisdom of generations before them, as manifest in The View through Wes's impossible social and romantic intimacy with a pre-AIDS generation of doomed queer characters.

IV. Exposed Seams: Constructing Identity in Performance

The View's plot centers on Wes's character development as he gets to know each of the cast-patrons before his trip back in time ends at 7:53 p.m., one moment before the fire overtakes the bar: the fire never enters the stage, the tragedy never reenacted. In this way, the narrative emphasizes the interpersonal connections across generations rather than spectacularizing trauma. We learn that, characteristic of millennial stereotypes, Wes struggles with anxiety and disillusionment fostered by obsessive relationships to "little white pills," social media, reality television, and fashion labels.76Vernon, The View UpStairs, 58. Spending time with the baby boomer patrons, he learns to appreciate face-to-face human engagement unmitigated by Instagram, even falling in love with Patrick without Grindr or Tinder or texting. Meanwhile, Wes learns how the patrons struggle to survive, rendering visible the ways in which much of 1970s LGBTQ+ life was encumbered by violences that still threaten in the twenty-first century: conversion therapy (Patrick's song "Waltz"), homelessness (Dale's song "Better than Silence"), and immigration (Inez's song "The Most Important Thing"). The exposition builds with these personal encounters until, suddenly, police sirens blare. The bar's beloved Puerto Rican drag queen Freddy/Aurora Whorealis (Michael Longoria) staggers in with his mother Inez (Nancy Ticotin), bloody and beaten. The Cop (Richard E. Waits) barges in, harasses patrons, demands identification, and threatens violence until the patrons pay him off.77Vernon, The View UpStairs, 39–42. The violence began on the street; when the Cop assaulted Freddy and Inez, a suitcase carrying his drag costume fell open. They escape arrest for violating the New Orleans cross-dressing ban, but the drag wardrobe is lost. Freddy laments, "What am I going to wear?"78Vernon, The View UpStairs, 49. Enter Wes—a fashion designer.

The ensuing scene builds to the musical's narrative climax as the characters facilitate Aurora Whorealis's drag performance. Channeling Scarlett O'Hara in the iconic green curtain dress scene from Gone with the Wind, Wes rips down the drapes wilting across the bar windows and seizes a roll of duct tape. In a flash, the entire Lounge mobilizes to help Freddy become Aurora. Again, the immersive staging engages the audience in the excitement and chaos of the moment. Freddy and Inez run stage right into the audience risers where they style Aurora's hair and makeup just two feet from the nearest audience-patron. Stage left and up the risers, Wes and Patrick immerse themselves near the last row to construct Aurora's wardrobe. Audience-patrons twist in their seats, craning their necks to follow the action. The spatial arrangement builds awkwardness and delight in our unexpected eye contact with other audience-patrons—an embodied moment of chaotic pathos that coincides with the character-patrons' experiences.79Mélissa Bertrand, "Performative Theatre: A Queer Theatre?" Whatever 3 (2020): 229. This staging evinces Mélissa Bertrand's concept of "trans-theatre," which I develop more thoroughly later in this essay. Here, Bertrand's emphasis on the body in queer performance implicates not just the performer, but the audience: "the body is given a major role . . . For the audience, it also implies to question the way we position ourselves as viewers of the show. The power of the gaze must be redefined, and queer sequences of theater can help rethink it." The triumphant progression to Aurora Whorealis's drag performance builds as the cast sings "Completely Overdone." Wes shrieks in delights at his frock: "It's like Count Dracula and Miss Whoopi Goldberg in Sister Act having a kiki in outer space!"80Vernon, The View UpStairs, 52.

The staged construction of Aurora Whorealis's overdone look recalls Bryant Alexander's critical affection for the exposed seams of so-called "bad" drag: "Sometimes I like seeing the seams . . . it is the seams that seemingly call my attention to the constructedness of the venture."81Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again," 351. He suggests that visible drag "seams" offer a metaphor for resisting a dangerous homogenizing trend that emerged in the early 2000s, one that deployed "queer" as an "inclusive signifier" to unify all manifestations of LGBTQ+ subjectivity.82Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again," 349. Alexander warns that "queer" discourses gloss over difference and risk silencing "any discussion that links perception, practice, performance and the politics of sexual identity to race, ethnicity, culture, time, place and the discourses produced within these disparate locations."83Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again," 349–50. The View's on-stage construction of Aurora Whorealis's drag look refuses such homogenizing erasure by drawing attention to the character's particularity as Puerto Rican, gay, man, son, and drag queen in pre-radicalized 1973 New Orleans. Revealing the multiple facets of Freddy/Aurora highlights not only individual particularity but also shared experience, as homophobic police brutality keenly resonates with a 2017 pro-LGBTQ+ audience in New York City sitting less than a mile from the Stonewall Inn. Freddy, a Spanish-speaking son of a Puerto Rican immigrant, complicates the Black/white dichotomy that has long falsely characterized the multiethnic, multinational US South. Aurora Whorealis, a blonde drag star with a communally constructed look, rejects singular constructs of identity as she "werks" a wardrobe manufactured from manifold referents across time, place, and subjectivity.

Aurora's multilayered frock in the original production (designed and created by Anita Yavich) evokes generations of pop culture and fashion icons that would have been impossible to assemble in 1973. Evoking Scarlett's curtain dress in/as drag, The View alludes to the season two premiere of RuPaul's Drag Race, "Gone with the Window," wherein contestants create a look from a set of window coverings and compete in drag performance.84"Gone with the Window." RuPaul's Drag Race, season 2, episode 1, "Gone with the Window," produced and hosted by RuPaul, aired February 1, 2010, on Logo. Wes exclaims, "I love this! I feel like I'm on Project Runway," further highlighting the precursor series that influenced RuPaul.85Vernon, The View UpStairs, 50. The curtains are crafted into a "nun's habit" that Aurora wears as she takes the stage to sing "Sex on Legs."86Vernon, The View UpStairs, 66. After the first chorus, she throws off the habit to reveal a frock clearly reminiscent of Madonna's "Vogue" looks, merging the superstar's 1990 music video and subsequent MTV Video Music Awards performance. But Wes's version of the dress uses "knick-knacks taken from the bar": the iconic cone bra fashioned in duct tape (music video), seventeenth-century panniers out of red solo cups (VMAs).87Vernon, The View UpStairs, 67. Though the costume begins with Scarlett's South, the underdress moves to New York City and reclaims "voguing" as an invention of Black and Latina/x queens of ball drag culture in the 1960s–1980s.

Aurora further strips off her panniers and climbs atop the grand piano for the song's climax; her cones explode into party hats with clown heads as confetti shoots out toward the audience. As the song winds down, Aurora relinquishes the clown bra for a final version made from Mardi Gras beads in concentric circles of purple, green, and gold. What stable category of gender identity lies beneath Aurora's cone bra? Clown heads and confetti. Mardi Gras gender play. Absurd constructed spectacle. Vernon's production asserts that a search for one singular, glossing identity misses the point; gender identity is always performative, always performance, indeed is constituted through the performance.88The performativity of Aurora Whorealis's manifold, evolving identifications might also be read through Bertrand: "At the crossroads between the notions of an actor•tress carrying a character's fictional identity through its own body, and that of a performer assuming their personal history and using it as a creative material, a new dynamic emerges, a more dialectical and complex positioning. In shows integrating queer themes, physical identity is located on a breach, on a border. This type of event includes what I would call 'bodies in trans-' or a 'theatre in trans-'." This is understood through the multiple terms that the prefix suggests, "'trance (transe in French), transition, transformation, transidentity, transgression, transfer…" Bertrand, "Performative Theatre," 215, (ellipses original). Exposing the seams of Aurora's constructed look and salvaging icons from disparate histories leverages drag performance as activism that simultaneously constitutes selfhood. Aurora's drag show reclaims these shared histories for the historic Up Stairs patrons and the cast- and audience-patrons participating in her reclamation in the present day.

In constructing Aurora's costume, Wes self-actualizes, too. He creates and manifests the fashion designer facet of his identity: "I forgot how good it feels to actually create . . . This cheap roll of duct tape is giving me life!"89Vernon, The View UpStairs, 53. The act of creation returns to Wes a sense of self, underscoring Katie R. Horowitz's important intervention in gender performativity theory that drag is not merely discursive but constitutive of identity.90Katie R. Horowitz, "The Trouble with 'Queerness': Drag and the Making of Two Cultures," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38, no. 2 (2013): 303–326. "[D]rag [is] in fact productive of the identity that [many gender scholars] claim it merely expresses," Horowitz explains, "drag does far more identity work than an argument premised on the distinction between stage performance and the performance of everyday life can convey."91Katie R. Horowitz, "The Trouble with 'Queerness,'" 311. She cites her field research at an LGBTQ+ bar in Cleveland, Ohio, where many of the drag kings and queens expressed that they feel their "drag self is in many ways more real than [their] real (i.e., offstage) self."92Katie R. Horowitz, "The Trouble with 'Queerness,'" 312. This inextricability of staged versus "offstage" identity resonates in Mélissa Bertrand's 2020 concept of "trans-theatre," which extends Josette Féral's "performative theatre" to the role of the body in queer performance. For Bertrand, a trans-theatre "go[es] beyond the dualisms that oppose, among other things, theatricality and performativity, the fictional identity of the character and the physical identity of the performer."93Bertrand, "Performative Theatre," 216. Undermining the distinction between what is "real (i.e., offstage)" and what is performed on stage, both Bertrand's and Horowitz's frameworks explicate why Wes is so enlivened by the staged act of creation; the act (i.e., action and performance) both manifests his character development and moves the plot forward.

V. "We all want the same thing": LGBTQ+ Genealogy, Futurity, Coalition

Importantly, Wes's self-constituting act also necessarily reclaims racial histories of enslavement evoked by the Gone with the Wind allusion, mirroring Aurora's reclamation of voguing. In Margaret Mitchell's scene, also depicted in the 1940 film, Scarlett commands Mammy to make her a costume from "moss-green velvet curtains" to perform southern belle planter-class drag so she can seduce "three hundred dollars" from Rhett Butler.94Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind, 50th Anniversary Commemorative Edition (New York: Avon Books, 1986), 535, 513; Sam Killerman, "Vocabulary Extravaganza," The Safe Zone Project, accessed February 3, 2019, https://thesafezoneproject.com/activities/vocab-extravaganza/; My use of "drag" to characterize Scarlett's performance in the green velvet dress is intentional. As Killermann defines, the term "drag queen" indicates "someone who performs femininity theatrically." Scarlett's embodiment, before donning Mammy's green dress, is marked by hard labor, starvation, and poverty, all which manifest on her body: "breasts . . . so small," a "scrawny neck and hungry cat eyes and raggedy dress" (Mitchell, 534 and 525). In order to seduce Rhett into giving her the money, she must perform a specific form of femininity, the carefree southern belle who is so "bored" from a life of leisure that she decided "to take a trip and have a good time" (Mitchell, 565). This is, of course, a complete lie, and she must conceal the truth by suppressing her fury at him, feigning tears, and hiding her eyes when she feels she has triumphantly hooked him (Mitchell, 564–571). When Rhett discovers the deception, he says, "You wanted something from me and you wanted it badly enough to put on quite a show" (Mitchell, 570). In the same way that drag queens perform a wide range of femininity across race, class, age, and culture, so too does Scarlett perform drag southern belle. Vernon's queer adaptation rewrites the racial logic of labor inherent in Mammy's formerly enslaved status; Wes seizes the challenge of garment creation with agency and self-determination. The inverse of racial obedience to white supremacy, Wes demonstrates his generative power to constitute meaning out of salvaged refuse, a clear metaphor for the reclamation and adaptation of violent, erased histories. As his lover Patrick affirms, "You just made a dress out of nothing."95Vernon, The View UpStairs, 47. The plot's climax in the drag show figures a key moment of Wes's character development; he realizes his own creative power, demonstrating how artistic production can galvanize queer (and) Black agency by reclaiming histories and historic icons as tools of affective change in the present. In creative work, Wes constitutes his identity from a traumatic history, demonstrating agency over his own future. As Patrick and Wes affirm in their lover's duet, "It's our story and the ending's ours to write."96Vernon, The View UpStairs, 82.

Patrick and Wes's ethic mirrors the playwright's own. Perhaps the most important feature of The View's constitutive performance was Vernon's own goal in composing the musical. Vernon explains in our interview that writing The View was motivated by a need for mentorship from a lost LGBTQ+ generation, not only the Up Stairs victims but all who perished in the 1980s AIDS epidemic:

It was about wanting to understand my own history. Growing up I didn't have any queer mentors to help me figure out how to exist in this world. And, you could say maybe that's because of the AIDS epidemic: a link in the chain of mentorship might have been broken. I wanted to go back to the seventies to exist in a pre-AIDS world to kind of understand my lineage as an LGBTQ person and understand where I came from and if that could, at all, help me figure out how to navigate this time period that we're in [today in 2017], which is very fraught and bizarre.97Vernon, interview by author.

For Vernon, composing The View fostered new relationship possibilities across impossible limits of time and space—as well as the ontological divide separating the living and the dead—which helped to constitute their "own history" and queer identity.98Taraneh, "Pop-Culturalist Chats with Max Vernon," Pop-Culturalist, September 18, 2018, http://pop-culturalist.com/pop-culturalist-chats-with-max-vernon/?fbclid=IwAR2EbOmNg5fbr_MtK_sVsnrKuIWRH0_kSHncmNtBrhnxCw4_K6botNev9Dc. By reaching back into history through performance, their creative work taps into a very personal longing and loss.

On World AIDS Day 2018, Vernon posted a public Facebook memorial honoring their uncle who, if not for AIDS, might have been an LGBTQ+ mentor:

I do not know a whole lot about my uncle Robert, the only other queer person from my family history . . . He became addicted to Heroin- not sure if it was the needles or gay sex that caused him to seroconvert, but he became HIV positive and most of my memories of him growing up involve visiting him in hospitals.

Towards the end of his life I know he cleaned up, worked as a janitor, and had a solid community of friends around him in Minneapolis. My uncle Robert died of aids when I was around 10 years old. He left me a package of rainbow socks bc I think in the back of his mind he knew I was also queer. At this point I only have one pair left- the green socks, and they're full of holes. I can't bring myself to throw them out though... Anyway that's my #worldaidsday story. With Prep, etc it's a different era today (at least in this country) but I mourn the collective loss for our community, and I hope my many friends who are + know how much I love and appreciate them. ❤️🧡💛💚💙💜🖤99Max Vernon, "I do not know," Facebook, December 1, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/MaxVernonMusic/posts/101.

The absence of knowledge about their uncle Robert's life compounds Vernon's grief over his death and orients their relationship to a queer genealogy through the AIDS epidemic. Vernon begins with the pain of not knowing, and they conclude with a metaphor of incompleteness in the gifted "green socks . . . full of holes." Their need for connection underscores a lost intergenerational relationship with "the only other queer person in [their] family history." Denied inheritance of familial queer genealogy, Vernon created The View UpStairs, imitating a mentorship with their uncle's generation that works around the impossibility of time, space, and death.

Likewise, The View brings its cast- and audience-patrons into new modes of relationality with imagined subjectivities of LGBTQ+ people who lived pre-AIDS and were abandoned by their nation in the epidemic. It compels the audience to collectively face the epidemic's "impossible gender/political situation," to use Goldberg's phrase, of a pre-radicalized LGBTQ+ New Orleans alongside the enduring legacy of the Reagan administration's institutional abandonment (1981–1989)—a legacy that would doom the 1973 patrons' future and continue to shape the present for the 2017 cast- and audience-patrons.100During Reagan's two-term presidency, nearly 253,000 new cases were diagnosed, and 230,000 or 91% of those diagnosed died as a result of the disease between 1981 and 1992, "HIV and AIDS---United States, 1981--2000," Morbid and Mortality Weekly Report 50, no. 21 (Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, June 1, 2001): 430–434.. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5021a2.htm. Wes explores this generational tension in "The Future Is Great," which voices queer millennial reflection to subvert belief in the teleological progression of LGBTQ+ rights. Talking to the 1973 patrons, Wes sings, "But I guess you're also lucky / living in the seventies. / There's no need for wearing condoms / you can slut it up guilt-free. / Nowadays we have fancy drugs / to help us all forget… / how the eighties came killed all your friends / you just don't know it yet."101Vernon, The View UpStairs, 58. Wes's simultaneous envy and fear for the Up Stairs generation demonstrates how LGBTQ+ millennials would come to experience HIV/AIDS under vastly less deadly conditions, many through secondhand history (e.g, "With Prep, etc. it's a different era today"). Having lost their uncle to that epidemic, Vernon, a millennial themself, feels the loss keenly and craves historical wisdom to constitute their own selfhood amid another hostile, anti-gay, transphobic, and racist recent presidential administration.

Throughout the musical, dialogue alludes to then recently inaugurated Donald Trump until the post-fire denouement when The View's contemporary intervention reaches fever pitch. Wes grieves the Lounge victims and traces its legacy through Pulse and the 2016 election. "This shit isn't better!" he shouts, "They're killing us. Fifty people just died in Orlando . . . Look at who's running this country! . . . OUR VICE PRESIDENT BELIEVES IN CONVERSION THERAPY!"102Vernon, The View UpStairs, 92. Jeremy Pope's performance of Wes's climactic line is desperate and immediate; he manifests the very real fear that the cast- and audience-patrons feel intimately as we anticipated the first of what would be many racist, nationalist, and anti-LGBTQ+ policies that the Trump/Pence administration would eventually enact.103The first directly anti-LGBTQ policy was announced that following July in 2017, when Trump tweet-announced the so-called "Trans Ban" in the US military that "the Administration began implementing . . . on April 12, 2019." "Transgender Military Service," Human Rights Campaign, last modified October 1, 2019, https://www.hrc.org/resources/transgender-military-service. In the immediacy of Wes's terror, the audience is brought to crisis and shared experience with the 1973 patrons. Wes reminds us that "this shit isn't better," a wake-up call against declining vigilance in a post-Obergefell political moment, and perhaps also a rebuke of guaranteed future betterment idealized in Dan Savage and Terry Miller's It Gets Better Project.104The home page of the It Gets Better Project reads, "The It Gets Better Project inspires people across the globe to share their stories and remind the next generation of LGBTQ+ youth that hope is out there, and it will get better" (emphasis mine); It Gets Better Project, accessed June 25, 2020, https://itgetsbetter.org. In either or both contexts, historic-, cast-, and audience-patrons are experientially united, haunted by dangerous futures. We are compelled to recognize how we constitute an intersectional collective despite the (im)possibilities of time, space, and subjectivity by confronting a national genealogy of hostile anti-LGBTQ+ policy tracing back from Trump, through Clinton, Reagan, Eisenhower, and beyond.105The homophobic policies of Trump and Reagan are outlined above. Importantly, anti-LGBTQ+ policy has been enacted by conservative and liberal administrations; President Bill Clinton instituted the discriminatory "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" military policy in 1993 forcibly closeting LGBTQ+ service people and signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law in 1996, prohibiting federal recognition of gay marriage. Eisenhower famously authorized the McCarthy-era Lavender Scare that terrorized homosexual Americans under anti-communist pretenses.

The View's immersive melodramatic pathos as executed in Pope's captivating performance manifests Goldberg's claim that melodrama can "work[] the system against itself" to foster opposition without necessarily changing the structures that inhibit LGBTQ+ life.106Goldberg, Melodrama, 160. The musical "open[s] a space of irresolution," and in that space, "[m]elodrama remediates [in the] double implication of the verb."107Goldberg, Melodrama, 4, xv. That is, The View confronts the impasse of time-space possibility for LGBTQ+ mentorship, and it thereby enacts the primary and secondary definitions of the verb "remediate." It conceptually remedies, or fixes again, oppressive ideological structures that inhibit "human flourishing" by recovering the erased arson attack and calling for resistance in the present day. The production also acts as a continual intermediary, mediating between what is possible (i.e., intimacy between cast- and audience-patrons) and what is impossible (i.e., mentorship by deceased historic-patrons and AIDS victims). The melodramatic mode in Vernon's adaptation does not simply re-present: it constitutes new possibilities for coalition against impossibility, however limited they may be.

The View UpStairs's immersive, melodramatic adaptation of nellydrama and drag performances that animated the 1973 Up Stairs Lounge subverts potential toward national voyeurism that recoiled local arson survivors at the arrival of those "fairy carpetbaggers." Vernon refuses to stage the fire's carnage, exploit the individual bar patrons, or reduce the event to mere symbol. In adapting the Lounge's performance genres, The View constructs a collective that links the cast and audience back to the generation who drank, prayed, performed, and lived in so many 1970s gay bars around the United States, imagining future possibilities for limitlessly diverse forms of LGBTQ+ subjectivity, relationality, and resistance. Indeed, such possibilities resonate most clearly in the words of Vernon's adapted MCC Reverend Richard: "We have too many people against us to be against each other. Maybe we have different ideas on how to get there, but we all want the same thing."108Vernon, The View UpStairs, 48.

About the Author

Stephanie Rountree is an assistant professor at the University of North Georgia. She is co-editor of Remediating Region: New Media and the U.S. South (Baton Rouge: LSU Press 2021) and Small-Screen Souths: Region, Identity, and the Cultural Politics of Television (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2017).

Acknowledgements

This essay manifests years of discussions with Dr. Ryan Prechter on his doctoral research on gay New Orleans and The View UpStairs. He introduced me to both the historic Up Stairs Lounge fire and Vernon's musical. Without his collaboration, this article would not exist. Similarly, I am deeply grateful to the external reviewers and editorial team at Southern Spaces, whose generous feedback helped shape my argument in important ways.

Recommended Resources

Text

Caron, Christina. "Overlooked No More: Bill Larson, Who Became a Symbol of Gay Loss in New Orleans." New York Times. June 26, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/26/obituaries/bill-larson-overlooked.html.

Delery-Edwards, Clayton. The Up Stairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-Two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014.

Fieseler, Robert W. Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation. New York: Liveright, 2018.

Goldberg, Jonathan. Melodrama: An Aesthetics of Impossibility. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Horowitz, Katie R. "The Trouble with 'Queerness': Drag and the Making of Two Cultures." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38, no. 2 (2013): 303–326.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Prechter, Ryan. "Gay New Orleans: A History." PhD diss., Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu.

Web

Fieseler, Robert W. "The UpStairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People. Its Legacy Still Haunts Black Gay New Orleans." The Daily Beast, May 13, 2019. https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-upstairs-lounge-fire-killed-32-people-its-legacy-still-haunts-black-gay-new-orleans.

Flax-Clark, Aidan. "The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire, Ep. 229." New York Public Library: Library Talks Podcast. September 2, 2018. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2018/08/31/untold-story-stairs-lounge-fire.

Last Call: New Orleans Dyke Bar History Project. "Podcast." Accessed November 4, 2021. http://www.lastcallnola.org/podcast/.

LGBT+ Archives Project of Louisiana. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.lgbtarchiveslouisiana.org/.

Madden, Pete. "City of New Orleans Quietly Launches Search for Lost Remains of UpStairs Lounge Fire Victim." ABC News. August 31, 2018. https://abcnews.go.com/US/city-orleans-quietly-launches-search-lost-remains-upstairs/story?id=57527498.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Excerpts taken from the following reviews found on Max Vernon's website: Lina Landstroem, "Queer History on Stage: A Review of The View UpStairs by Max Vernon," Public Seminar, March 1, 2017, https://publicseminar.org/2017/03/when-a-bar-was-your-home/; Zackary Stewart, "KPOP," TheaterMania, September 22, 2017, https://www.theatermania.com/off-broadway/reviews/kpop_82533.html; Elisabeth Vincentelli, "Review: A Gay Nightclub Tragedy, Decades Before Orlando, in 'The View UpStairs'," The New York Times, March 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/07/theater/the-view-upstairs-review.html. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Robert W. Fieseler, Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2018), 227. |

| 3. | Max Vernon, interview by author, September 8, 2017. |

| 4. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, xix. |

| 5. | See the front page spread of The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), June 25, 1973, Monday Morning Edition, 1. |

| 6. | Vernon, interview by author; Fieseler, Tinderbox, 70. |

| 7. | Clayton Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-Two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014); Vernon, interview by author; see also Johnny Townsend, Let the Faggots Burn: The UpStairs Lounge Fire (Bangor, ME: BookLocker, 2011). Townsend's 1989–90 archival work informed Delery-Edwards's research. |

| 8. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 2. |

| 9. | Townsend, Let the Faggots Burn, vii. |

| 10. | It is important to note that some inconsistencies exist in Delery-Edwards's text, as well. Today, Robert W. Fieseler's Tinderbox (2018) is considered a more thorough, accurate record of the fire. |

| 11. | Max Vernon, The View UpStairs (New York: Samuel French, 2017), 45. |

| 12. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 45. |

| 13. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 10. |

| 14. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 10. |

| 15. | Although the most well-known, the Stonewall Uprising was not the first instance of LGBTQ+ resistance. The Cooper Do-Nuts Riot (1959) as well as the Compton's Cafeteria Riot (1966), both in California, precede Stonewall. Many have argued that Stonewall became central to the development of Gay Liberation largely as a result of practices of memory (organized activism) that arose to commemorate the event, such as the Christopher Street Liberation Day (1970), often cited as the first gay pride event in the country. |

| 16. | Ryan Prechter, "Gay New Orleans: A History" (PhD diss, Georgia State University, 2017), https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/60/. |

| 17. | The three white Tulane murderers intended to "roll a queer," or assault a gay person, the night they killed Rios. Trial testimony revealed that the murderers bragged about the assault after they left Rios for dead. Clayton Delery-Edwards, Out for Queer Blood: The Murder of Fernando Rios and the Failure of New Orleans Justice (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 97. |

| 18. | Delery-Edwards, Out for Queer Blood, 148. |

| 19. | James Karst, "Halloween Cross-Dress Costumes Lead to 21 Arrests in 1952: Our Times," The Times-Picayune, October 18, 2015, https://www.nola.com/news/crime_police/article_4522e6d7-b6bb-5143-a772-ee5712675293.html. |

| 20. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. |

| 21. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 21. |

| 22. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 25, 31–32. |

| 23. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 34. |

| 24. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. |

| 25. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 24–25. |

| 26. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 25. |

| 27. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 33. |

| 28. | Jonathan Goldberg, Melodrama: An Aesthetics of Impossibility (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 160. |

| 29. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 227. |

| 30. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. |

| 31. | Bryant Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again (Or Queer Theory as Drag Performance)," Journal of Homosexuality 45, no. 2–4 (2003): 351. |

| 32. | Betty Luther Hillman, "'The most profoundly revolutionary act a homosexual can engage in': Drag and the Politics of Gender Presentation in the San Francisco Gay Liberation Movement, 1964–1972," Journal of the History of Sexuality 20, no. 1 (2011): 158. |

| 33. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. |

| 34. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 29. |

| 35. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 227. |

| 36. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 50 (ellipses original); See also Townsend, Let the Faggots Burn, 184–185. |

| 37. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 71. |

| 38. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 183. |

| 39. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 187. |

| 40. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 66. |

| 41. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 191. |

| 42. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 164. |

| 43. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 164. |

| 44. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 111–112. |

| 45. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 63, 146–149. |

| 46. | Delery-Edwards, 63, 146–149. |

| 47. | Fieseler, Tinderbox, 228. |

| 48. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 147. |

| 49. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 146. |

| 50. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 147. |

| 51. | Ryan Prechter, "Gay New Orleans: A History." |

| 52. | The View UpStairs, written and composed by Max Vernon, dir. Scott Ebersold, chor. Al Blackstone, performed by Jeremy Pope, Taylor Frey, Frenchie Davis, Benjamin Howes, Michael Longoria, Ben Mayne, Randy Red, Nancy Ticotin, Richard E. Waits, and Nathan Lee Graham, New York, Lynn Redgrave Theater, March 25, 2017. |

| 53. | Delery-Edwards, The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, 20. |

| 54. | Josephine Machon, Immersive Theatres: Intimacy and Immediacy in Contemporary Performance (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013); See especially "The Scale of Immersivity," 93–102. |

| 55. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 7. |

| 56. | Machon, Immersive Theatres, 98. |

| 57. | Machon, Immersive Theatres, 99–100. |

| 58. | Linda Williams, "Melodrama Revised," in Refiguring American Film Genres: History and Theory, ed. Nick Browne (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 51. |

| 59. | Vernon cautions, "While it's important to carve out true emotional beats for the characters, never let the piece veer into melodrama." Vernon, The View UpStairs, 6. |

| 60. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 9–11. |

| 61. | The View UpStairs, 73; At the time of this publication, the former Up Stairs Lounge now houses office space and the kitchen for The Jimani sports bar. |

| 62. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 8, 5; Vernon, interview by author. |

| 63. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 5; For a rich discussion of performance theater that stages LGBT+ engagement in religious liturgy, see Lusie Cuskey, "The Liturgy that Dare Not Speak Its Name: Religious Engagement and Affective Memory as a Site of Queer Activism in Musical Theatre," Ecumenica: Performance and Religion 13, no. 1 (2020): 52–68. |

| 64. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 8; Vernon, interview by author. |

| 65. | Vernon explains, "And so, I think in many ways, where they have these anti-sodomy laws in the South, and where regularly, if a gay bar was raided and they took your ID, your name could be printed in the paper, and you could lose your job. You could lose housing. I think they didn't have the same freedoms as New York to be as visible, so they had a different mode of survival of how they had to exist in these spaces like the Up Stairs Lounge." Vernon, interview by author. |

| 66. | Robert W. Fieseler, "The UpStairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People. Its Legacy Still Haunts Black Gay New Orleans," The Daily Beast, May 13, 2019, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-upstairs-lounge-fire-killed-32-people-its-legacy-still-haunts-black-gay-ne. |

| 67. | Fieseler, "The UpStairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People." |

| 68. | Regina Adams quoted in Fieseler, "The Up Stairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People." |

| 69. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 7. |

| 70. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 5. |

| 71. | José Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 1. |

| 72. | Muñoz, Disidentifications, xiv. |

| 73. | Vernon, interview by author. |

| 74. | Goldberg, Melodrama, 21. |

| 75. | Goldberg, Melodrama, 156. |

| 76. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 58. |

| 77. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 39–42. |

| 78. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 49. |

| 79. | Mélissa Bertrand, "Performative Theatre: A Queer Theatre?" Whatever 3 (2020): 229. This staging evinces Mélissa Bertrand's concept of "trans-theatre," which I develop more thoroughly later in this essay. Here, Bertrand's emphasis on the body in queer performance implicates not just the performer, but the audience: "the body is given a major role . . . For the audience, it also implies to question the way we position ourselves as viewers of the show. The power of the gaze must be redefined, and queer sequences of theater can help rethink it." |

| 80. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 52. |

| 81. | Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again," 351. |

| 82. | Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again," 349. |

| 83. | Alexander, "Querying Queer Theory Again," 349–50. |

| 84. | "Gone with the Window." RuPaul's Drag Race, season 2, episode 1, "Gone with the Window," produced and hosted by RuPaul, aired February 1, 2010, on Logo. |

| 85. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 50. |

| 86. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 66. |

| 87. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 67. |

| 88. | The performativity of Aurora Whorealis's manifold, evolving identifications might also be read through Bertrand: "At the crossroads between the notions of an actor•tress carrying a character's fictional identity through its own body, and that of a performer assuming their personal history and using it as a creative material, a new dynamic emerges, a more dialectical and complex positioning. In shows integrating queer themes, physical identity is located on a breach, on a border. This type of event includes what I would call 'bodies in trans-' or a 'theatre in trans-'." This is understood through the multiple terms that the prefix suggests, "'trance (transe in French), transition, transformation, transidentity, transgression, transfer…" Bertrand, "Performative Theatre," 215, (ellipses original). |

| 89. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 53. |

| 90. | Katie R. Horowitz, "The Trouble with 'Queerness': Drag and the Making of Two Cultures," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38, no. 2 (2013): 303–326. |

| 91. | Katie R. Horowitz, "The Trouble with 'Queerness,'" 311. |

| 92. | Katie R. Horowitz, "The Trouble with 'Queerness,'" 312. |

| 93. | Bertrand, "Performative Theatre," 216. |

| 94. | Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind, 50th Anniversary Commemorative Edition (New York: Avon Books, 1986), 535, 513; Sam Killerman, "Vocabulary Extravaganza," The Safe Zone Project, accessed February 3, 2019, https://thesafezoneproject.com/activities/vocab-extravaganza/; My use of "drag" to characterize Scarlett's performance in the green velvet dress is intentional. As Killermann defines, the term "drag queen" indicates "someone who performs femininity theatrically." Scarlett's embodiment, before donning Mammy's green dress, is marked by hard labor, starvation, and poverty, all which manifest on her body: "breasts . . . so small," a "scrawny neck and hungry cat eyes and raggedy dress" (Mitchell, 534 and 525). In order to seduce Rhett into giving her the money, she must perform a specific form of femininity, the carefree southern belle who is so "bored" from a life of leisure that she decided "to take a trip and have a good time" (Mitchell, 565). This is, of course, a complete lie, and she must conceal the truth by suppressing her fury at him, feigning tears, and hiding her eyes when she feels she has triumphantly hooked him (Mitchell, 564–571). When Rhett discovers the deception, he says, "You wanted something from me and you wanted it badly enough to put on quite a show" (Mitchell, 570). In the same way that drag queens perform a wide range of femininity across race, class, age, and culture, so too does Scarlett perform drag southern belle. |

| 95. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 47. |

| 96. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 82. |

| 97. | Vernon, interview by author. |

| 98. | Taraneh, "Pop-Culturalist Chats with Max Vernon," Pop-Culturalist, September 18, 2018, http://pop-culturalist.com/pop-culturalist-chats-with-max-vernon/?fbclid=IwAR2EbOmNg5fbr_MtK_sVsnrKuIWRH0_kSHncmNtBrhnxCw4_K6botNev9Dc. |

| 99. | Max Vernon, "I do not know," Facebook, December 1, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/MaxVernonMusic/posts/101. |

| 100. | During Reagan's two-term presidency, nearly 253,000 new cases were diagnosed, and 230,000 or 91% of those diagnosed died as a result of the disease between 1981 and 1992, "HIV and AIDS---United States, 1981--2000," Morbid and Mortality Weekly Report 50, no. 21 (Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, June 1, 2001): 430–434.. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5021a2.htm. |

| 101. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 58. |

| 102. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 92. |

| 103. | The first directly anti-LGBTQ policy was announced that following July in 2017, when Trump tweet-announced the so-called "Trans Ban" in the US military that "the Administration began implementing . . . on April 12, 2019." "Transgender Military Service," Human Rights Campaign, last modified October 1, 2019, https://www.hrc.org/resources/transgender-military-service. |

| 104. | The home page of the It Gets Better Project reads, "The It Gets Better Project inspires people across the globe to share their stories and remind the next generation of LGBTQ+ youth that hope is out there, and it will get better" (emphasis mine); It Gets Better Project, accessed June 25, 2020, https://itgetsbetter.org. |

| 105. | The homophobic policies of Trump and Reagan are outlined above. Importantly, anti-LGBTQ+ policy has been enacted by conservative and liberal administrations; President Bill Clinton instituted the discriminatory "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" military policy in 1993 forcibly closeting LGBTQ+ service people and signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law in 1996, prohibiting federal recognition of gay marriage. Eisenhower famously authorized the McCarthy-era Lavender Scare that terrorized homosexual Americans under anti-communist pretenses. |

| 106. | Goldberg, Melodrama, 160. |

| 107. | Goldberg, Melodrama, 4, xv. |

| 108. | Vernon, The View UpStairs, 48. |