Overview

In this excerpt from Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), Grace Hale sets the scene and introduces the major theme of her new book: how in the 1980s Athens youth built the first important small-town American music scene and the key early site of what would become alternative or indie culture. The second part of this Cool Town excerpt revisits the iconic Athens band Pylon through Hale's discussion of a 1980 video performance of their song "Danger."

Adapted from COOL TOWN: HOW ATHENS, GEORGIA, LAUNCHED ALTERNATIVE MUSIC AND CHANGED AMERICAN CULTURE by Grace E. Hale. A Ferris & Ferris Book. Copyright © 2020 Grace E. Hale. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press, www.uncpress.org.

An Unlikely Bohemia

We are hope despite the times.

R.E.M., "These Days" (1986)

In Athens, Georgia, in the 1980s, if you were young and willing to live without much money, anything seemed possible. Magic sparkled like sweat on the skin of dancers at a party or a club. Promise winked underfoot like the bits of broken glass embedded in the downtown sidewalks. A new world seemed to be emerging out of our creativity, our music and art, and our politics, but also the way we understood ourselves and related to each other.

In my memory, the weight of the air on summer nights made possibility seem like a substance I could hold in my hand. Always, local bands played and people listened—at practice spaces and house parties and venues like the 40 Watt. People went to hear their roommate or boyfriend or coworker play one night and urged everyone to come and see their group the next. Easy to make and easy to hear, live music was everywhere. We used it to reinvent and express ourselves and connect with each other. We used it to live.

After the clubs let out, the scene kept moving until dawn. Small groups climbed the fences at apartment complexes—no one would admit to living in one—and went skinny-dipping. Sometimes people walked to a big Victorian house on Hill Street and danced to mixtapes in the hall between the rolled-back pocket doors until their clothes dripped with sweat and their heads spun. Occasionally, at midnight, a small drama troupe would perform an original play up and down the aisles of the twenty-four-hour Kroger. Film buffs too young to see movies like Sleeper, Raging Bull, and Paper Moon when they came out watched them for free in the air-conditioned quiet of the seventh floor of the University of Georgia's library. Often, people paired up, going home with the person they were seeing or an acquaintance or someone they had just met. One perfect July night, I lay naked with a friend on the cool cement floor of a screen porch as the wet heat thinned and the crickets rasped and we talked about music until dawn. Possibility proved more addictive than the beer everyone drank and the drugs many people took.

We were unlikely people in an unlikely place. No one expected us to do these creative things. No one who mattered thought that we could make a new kind of American bohemia. Yet Athens kids built the first important small-town American music scene and the key early site of what would become alternative or indie culture.

We had grown up anything but alternative. Home was a new version of the South created by desegregation, interstates, air conditioning, and airports. Our parents had mostly enjoyed the rewards, a hard-earned success that had been knocked back in the last decade by the oil crisis, stagflation, and the Reagan recession. Our schools practiced a form of neglect that suggested racial integration was easy, feminism unnecessary, and gay sexuality nonexistent. None of that was true, of course, but white, middle-class kids often skated over the consequences.

On some vague level, we sensed that we were living in a changed and changing world, yet the adults around us seemed to be in denial, clinging to old ideas about life and work and community. The most visible alternative, the hippies and peace activists left over from an earlier generation's counterculture, appeared to have degenerated into caricature. Reading books and music magazines and talking to older Athens artists and University of Georgia professors, we learned about creative communities in Paris and London and New York, places that had nurtured earlier rebels from the Beats and the jazz musicians and the abstract painters to the rockers and the drag queens and the punks. Some of us even got to know nearby "folk" artists and musicians, people who followed their own visions right here at home. We longed to send our yawp over the roofs of the world, too, to live for music and art and sex, to be daring and original and important. Why the hell not? We did not want to be rednecks or racists or conservative Christians or live in subdivisions or work as middle managers. We dreamed not of the Reagan-era Sunbelt but of a different world, a new, new, new South. And in the university's libraries and archives and studios and galleries and concert halls and the town's old buildings, we found resources to try to make that world a reality.

The scene was our answer to what we understood as the failures and limits of our America. And our participation in this collective creativity transformed us. In my case, the scene took in an unhappy accounting major confused about politics and about six years later spit out a feminist and anti-racist scholar determined to live her life as art. Along the way, I waited tables and catered, made rugs and wall-hangings out of old clothes, took up painting and the cello, earned a master's degree in history, and cofounded and ran a local venue. When I left Athens to start a history PhD program elsewhere, I took that magical sense of possibility with me and used it to weather the perils of graduate school and the academic job market. My story was not unique. The scene changed everyone I knew. Middle-aged now, a historian and the mother of college kids myself, I can see how the things we learned—question the givens, find something to do that engages your passions, build community into whatever you do, and stop often for beauty and pleasure—radically transformed the trajectory of our lives.

From the late-seventies origins of bohemian Athens to the early nineties when Seattle became the center of American alternative culture, the Athens scene produced amazingly good music, from famous groups like the B-52s, R.E.M., and Widespread Panic to critics' darlings like Pylon and Vic Chesnutt and acts that built a grassroots fan base one show at a time, like the Squalls and Mercyland. But the scene also transformed the punk idea that anyone could start a band into the even more radical idea that people in unlikely places could make a new culture and imagine new ways of thinking about the meaning of the good life and the ties that bind humans to each other. The history of the Athens scene proves that people you would not expect in places you have not thought about can create a better world. It also reveals how cultural rebellion can transform human experience.

Of course, the music mattered. Athens musicians combined an arty, avant-garde approach that prized originality with its seeming opposite, a commitment to the pleasures of pop culture, rhythms that made you feel and move, and spectacle that made you stare. Reimagining the structures of rock music went hand in hand with having fun. Athens bands helped make this pop-art fusion an important part of the new overlapping music genres of college and alternative and indie rock. Because the Athens scene emerged so early in the transition between punk and indie, it also served as a model for kids trying to make their own music in other places not previously understood as having underground potential. If punk taught people that anyone could play, Athens taught them that this music making could happen anywhere, even in the South, even in small-town America.1Bernard Gendron, Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Tricia Henry, "Punk and Avant-Garde Art," Journal of Popular Culture 17, no. 4 (Spring 1984): 30. Another, early node of DIY culture in an unlikely place was the scene which formed in Akron and Cleveland, Ohio, two adjacent and then-deindustrializing cities, after the formation of Devo in 1973. See Calvin C. Rydbom, The Akron Sound: The Heyday of the Midwest Punk Capital (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2018). On the relationship between the Akron scene and Kent State University, see Tim Sommer, "How the Kent State Massacre Helped Give Birth to Punk Rock," Washington Post, May 3, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/how-the-kent-state-massacre-changed-music/2018/05/03/b45ca462-4cb6-11e8-b725-92c89fe3ca4c_story.html. See also the publication D.I.Y: The Do-It-Yourself New Music Magazine, published in Manhattan Beach, California, in 1980 and 1981. Issues included lists of clubs that would book punk and other kinds of new music, independent record stores, and college radio stations, as well as coverage of scenes in Cleveland, New York, Los Angeles, and a few other cities.

While bands created the most widely circulated forms of eighties alternative culture, the point was never only to make our own music. People in Athens and in other outposts of indie America were working on something more. We were trying to build authentic and meaningful lives in opposition to what we understood as the stifling conventions, false idols, and emptiness of modern middle-class American life. We were trying to save popular music, sure, but we were also attempting to create real places in which real people interacted with each other in order to boost real human flourishing. Surrounded by New Right politics, evangelical social conservatism, and corporate-dominated life, we worked to preserve the very idea of culture as a space of freedom and play and pleasure. And our efforts helped move the ideals we valued—a much more open and tolerant society, an appreciation for and investment in the local, a commitment to beauty and pleasure in everyday life, and a belief that what you do for a living does not define your identity—from the margins to the mainstream of contemporary life.

It is easy to scoff at our naivete and our ignorance—and even our arrogance—and to argue that the DIY notions we imagined as utopia gave way instead to today's start-up mentality, the gig economy, and ballooning inequality. Many people whose opinions I value want the story of Athens to follow a rise and fall arc. But this story distorts and simplifies the history of this scene and ignores the facts. And I am not ready to give up on the promise of alternative culture yet, not in my Athens of the past or in any possible Athens of the future.

Unlike many other places where eighties and nineties alternative culture flourished, contemporary Athens has not become a bohemian stage set for the top 10 percent of Americans, with a little bit of genuine creative culture clawing for survival among the rising rents. It has not been taken over by tech culture and "creative" entrepreneurship like Seattle, Brooklyn, and Austin. And it has not turned slick and rich with retirees and people with "family" money like many other college towns. Gentrification is occurring, but the area remains relatively cheap, isolated, hard to get to, and modest, especially outside the historic districts and areas close to campus. And somehow, within and even on the margins of the scene, wealth is still not something you want to brag about or display unless you want to be considered an idiot or a racist or a Republican. The currency remains DIY culture, and while you can buy other people's creativity and aesthetic sensibility, nothing is as cool as cultivating your own. While the scene is still too white, events like Hot Corner Hip Hop and venues like the World Famous have stretched the boundaries of Athens alternative culture to include African American musicians and fans of indie hip-hop. Today, bohemian Athens still works about as well as it ever did, nurturing a famous band here or there but always churning away at the less glamourous but arguably more important work of transforming the lives of suburban and small-town southern kids and giving them a vision of a bigger and more creative, open, and tolerant world.2Contrast Coran Capshaw, the manager of Charlottesville's most famous musical group, the Dave Matthews Band, with Bertis Downs, R.E.M.'s lawyer and manager, who still runs the business end of that former band. Capshaw is an entrepreneur who runs multiple companies and a real estate empire in the college town where I live now, while Downs spends most of his time as a local and national advocate for public schools.

Pylon's "Danger"

Sonically and visually, Pylon worked the contrast between flat, machine-like minimalism and ragged, southern-accented amateurism. Their songs used a four-on-the-floor disco beat to mash together punk's emotional excess and industrial repetition and detachment. The band may have been "safety conscious," but the raw, pounding sound did not make anyone feel safe. Band members turned uneven development—the collision between Athens as a small southern town and Athens as the home of a modern university and Athens as a peripheral industrial site—into a startlingly original sound, an audio portrait of postmodernity.

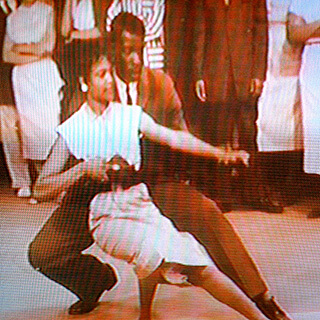

After Jim Fouratt left Hurrah, he and a partner opened Danceteria, a New York dance club that also showcased live bands. Video artists Emily Armstrong and Pat Ivers programmed the video lounge there, and they recorded one of Pylon's shows. The surviving footage reveals what Pylon looked and sounded like at the height of their power.3"Pylon-1980," online at https://vimeo.com/50389377. See also http://localeastvillage.com/2012/10/15/nightclubbing-pylon/, which described the video as part of Pat Ivers and Emily Armstrong's archive of punk-era concert footage being digitized for the Downtown Collection at N.Y.U.'s Fales Library.

The song "Danger" begins with a bass drum beat and lead singer Vanessa Briscoe Hay quietly alternating between making a "ssssss" sound and chanting works like "the sound of danger." Drum and voice hold the line as the bass rings out and a scattering of guitar notes compete with a clanging cymbal. Someone thinks to turn up the stage light, and Briscoe Hay's head and upper torso emerge from the dark. Michael Lachowski's bass builds, repeating a bouncing five-note phrase again and again, and the guitar and cymbal clang repeatedly. Briscoe Hay stares straight ahead at the audience, her eyes barely visible under a thatch of brown bangs, and hisses into the mic, impersonating a snake or a valve letting off steam, the sound equivalent of the machine in the garden.4Local East Village, "Pylon-1980."

On stage, Briscoe Hay and Lachowski's bodies and clothes create a kind of visual dissonance. Briscoe Hay wears a church dress gone wrong, its color a bit faded and its shape a little soft. As she shakes and twirls her head, a limp lace sleeve slips down her shoulder. Instead of a necklace, she wears her whistle. Her facial expressions alternate between lack and excess, an underplaying that suggests choked amateurism and an overplaying that evokes the entwined histories of blackface and drag.5Van Gosse, "Pylon Draws the Line," Village Voice, February 25, 1981, describes Briscoe Hay in a performance at the Rock Lounge in New York on Valentine's Day 1981 as, "shoeless with whistle, in a parochial-school blue smock and white blouse" (3).

As the song builds, Briscoe Hay spins like a windup whirling dervish, slowing down and speeding up according to the tension in her spring. As she dances, her moves accentuate her curves. The only sharp things here are her cheekbones. Her accent is somehow flat and yet also lushly southern. Like Cindy Wilson in the B-52s, Briscoe Hay both conjures and contradicts the multiple meanings of performing like a girl. In contrast, Lachowski is tall, hard, and thin, a pole of a man with slow, repressed gestures. He sticks out his tongue, and he turns his head a little, looking away from the crowd on one side and then the other. At times, he seems a little scared. His t-shirt and jeans refuse notice. In the critic Van Gosse's words, Lachowski and guitarist Randall Bewley look "like bike mechanics or sculptors" who perform a kind of "abstract hopping around, cute yet unposed."6Gosse, "Pylon Draws the Line," 3.

About a minute in, Briscoe Hay shakes her brown bangs from her brown eyes and half smiles, half grimaces at the audience as she increases the volume and the emotional intensity of her voice. "Dannnne . . . gerrrr," she sings, like a southern girl struggling to speak a foreign tongue, "Be careful. Be caw . . . tious." Drawing out the "caw" until it mimics the sound of a crow, she over-enunciates and turns her head for emphasis, like a teacher trying to force her students to pay attention. A delay effect sends the vocals echoing in all directions and conjures the large space of a factory or a church. With Briscoe Hay's vocal shift, the song explodes. The drums become fat and big and bullying. Sprays of a few guitar and bass notes and shouted words form achingly simple hooks. Then Briscoe Hay blows a long blast on her whistle right into the mic, and the sound of a safety alert at a factory or a foul in a gym rings out an elementary need. The serial riffs convey both the repetition of machinery and a growing urgency as volume and tempo slowly build. At the end, the guitar and bass sound like they are unwinding. Briscoe Hay begins to scream and moan, and the delay effect unravels her voice. The creamy skin of her chest shows just above her breast where her dress has slipped off her shoulder. Decreasing the volume and cutting the speed, she winds listeners out of the song on a wash of emotions that refuse to coalesce into any coherent form.

In person, Briscoe Hay sounded like a girl—she spoke in a soft, high voice with a deep southern accent. On stage, she developed a grown-up and powerful roar. Part beauty queen and part drag queen, she worked the intersections of white southern conventions of femininity and drag performance, Patti Smith's androgyny and Yoko Ono's arty shock and awe. The Danceteria video conveyed the charisma of the maturing band's live performances, an allure never quite captured on their recordings. Back in Athens, Vanessa's performances made other women think that if a sweet southern girl could do this, then they too might dare to dream.

That November, DB Records released Gyrate, Pylon's first album, recorded the previous spring in a three-day session at Stone Mountain Studios and produced by Kevin Dunn, a former member of Atlanta punk band the Fans who had also helped with the B-52s's and Pylon's singles. In December, Armageddon Records released the album in England. Critics raved. New Music Express named the record "one of the year's most fundamental rock and roll celebrations." Melody Maker worked the unlikeliness angle: "Buried deep in the land of rednecks, peanut farms and wave-yer-hat-and shout-yeehaw boogie bands, there's something stirring." Pylon made its first overseas tour, playing across England and a few dates in Europe in November and December. Back in New York, John Lennon was murdered. Briscoe Hay remembered getting out of a car in Liverpool and accidently stepping into a pile of flowers left as a makeshift memorial.7"Review of Gyrate," New Music Express, December 1980; Robert Holland, "After Hours," Red and Black, February 8, 1980, 5; "Interview with Danny Beard," Tasty World 3 [April 1985], 11; Jay Watson, "Local Groups Get Boost from DB Records," Red and Black, January 13, 1982, 1, 5; Briscoe Hay, "Vanessa's Version"; Briscoe Hay, interview; Bourne, interview; Biddle, interview; Rasmussen, interview. Bewley did the cover art for the album and former art student Bourne, then working in Atlanta at Beard's record store, did the art direction and design.

Reagan had been elected president just as the album came out, and many critics heard something political in the band's unique sound. Glenn O'Brien prefaced his positive review of Gyrate with a rant about the new political moment. He agreed with the president that America still believed in "those great ideals, those hopes and dreams." The problem for O'Brien was that collectively, Americans had lost "our national ability to identify facts, to absorb information and correlate it; in short, our ability to know anything." By really making you feel like dancing, by moving listeners and making them think, Pylon worked as an antidote to this know-nothingness.8Glenn O'Brien, "Glenn O'Brien's BEAT," Interview, March 1981, 62.

For critic Van Gosse, writing in the Village Voice, Pylon's new album was not just great; as the Reagan era began amidst "imperial decline and the sound of cowboy bluster," it was essential. "If there is any conceivable 'rock 'n' roll future,'" he argued, it lay "in the intrinsic values of a music that is kept blindingly simple, unsentimental, uncomfortable: that which embodies the particular contradictions of its historical epoch in three minutes of glorious noise." For Van Gosse, rock and roll meant "nothing more or less than controlled rhythmsmack, an exquisite tension and release embodied in sound." Pylon embodied "this formal truth right now in a way that only the Rolling Stones ever have before." After lovingly describing their sound and raving about the "hypnotic" Briscoe Hay, "shoeless with whistle," he returned to the importance of this kind of band in this kind of time. Before Pylon, "the class acts of post-everything modernism" came from "the most ancient bowels of decayed industrial capitalist, the dreary olde U.K." While many young Americans loved this music, "we're not really rotted enough yet ourselves. What was needed was something with a little frontier chutzpah, some rooty-toot-toot all-American get-up-an-go, to sing of our bodies electric and alone." Pylon, from "the proverbial sleepy college town," was that band.9Gosse, "Pylon Draws the Line," 61–62. Gosse's article offered very high praise considering how much good rock and roll came out in 1980, including Springsteen's The River, John Lennon's Double Fantasy, Pete Townshend's Empty Glass, David Bowie's Scary Monsters, Grace Jones' Warm Leatherette, Captain Beefheart's Doc at the Radar Station, The English Beat's I Just Can't Stop It, and Stevie Wonder's Hotter Than July, and albums by more underground acts like the Talking Heads' Remain in Light, Elvis Costello's Get Happy!, X's Los Angeles, The Clash's Sandinista!, and the Dead Kennedys' Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables.

New York Rocker's March 1981 Pylon cover story and interview "From Athens, Georgia: New Sounds of the Old South" did not so much argue as gush. The band's "utter lack of attitude" offered an antidote to big city jadedness: "Aren't y'all tired of patronizing arty-fartiness pawned off as entertainment?" Pushed to describe Pylon's sound, Lachowski called the band's music "temporary," in contrast to contemporary, rock. In the same issue, Vic Varney explained the new Athens scene under the headline "Nineteen Hours from New York," and New York Rocker printed photos of the next wave of bands: R.E.M., Love Tractor, and the Side Effects.10Karen Moline, "Pylon: From Athens, GA: New Sounds of the Old South," New York Rocker, March 1981, 15–17; Vic Varney, "'Nineteen Hours from New York': Small Town Makes Good," New York Rocker, March 1981. For more interesting writing about Pylon, see Robert Palmer, "Critics' Choices," New York Times, April 4, 1982; Guy Trebay, "Survey of the Week's Events: Pylon/dB's," Village Voice, April 20, 1982; "Pylon/'Crazy,'" New York Rocker, June 1982, 43; Steve Anderson, "Pylontechnics," Village Voice, November 9, 1982, 66; Stephen Holden, "Music: Pylon at the Ritz," New York Times, May 31, 1983, C15; Tom Carson, "Pylon Up Around the Bend," Village Voice, June 14, 1983, 84; Kim Taylor Bennett, "We Talked to Pylon's Michael Lachowski Because He's a Legend," Vice, August 14, 2014, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/6w3vw6/we-talked-to-michael-lachowski-from-pylon-because-hes-a-legend.

When the 40 Watt Club reopened with new ownership on West Clayton near the old Last Resort space, Pylon was the obvious choice to headline. Varney had exaggerated when he told New York Rocker that Pylon was essentially "commuting to New York." Despite touring with the Gang of Four in the Midwest and Canada and recording a new single, "Crazy"/"M-Train," and a second album, Chomp, band members still lived in Athens and spent a lot of time there. In January 1982, the group played a now-legendary show on campus, selling out the large Memorial Hall ballroom. That fall, Pylon packed the i and i, a warehouse-sized club that for a short time booked the new bands. In April of 1983, when the 40 Watt moved from Clayton Street to a bigger venue on Broad Street, only Pylon could headline the back-to-back closing and then opening shows and pack both rooms. Pylon ruled the scene that the band had done so much to create.11Vanessa Briscoe Hay interviews, T. Patton Biddle interview; Jay Watson, "'Athens' Finest' Play Tonight," Red and Black, January 13, 1982, 5; Moline, "Pylon: From Athens, GA"; T. Patton Biddle, better known as Pat the soundman, has the flyer for the Memorial Hall show with Pylon and Love Tractor on his website at https://www.patthewiz.com/.

In contrast, the New York-based B-52s hit something of a slump. After following up their debut album with 1980's successful Wild Planet, the group finally released Mesopotamia in early 1982, a David Byrne–produced recording that ended up being an EP because the band simply did not have enough new material. Most critics panned it. New York Rocker captured the prevailing sentiment: "This best-dressed act doesn't know what to do for an encore." Still, a lot of Athens folks headed down to Atlanta to catch the B-52s at the Fox, and Fred Schneider plugged his friend Jerry Ayers's band Limbo District, playing later that night at the Atlanta club 688. The next spring, the B-52s released Whammy!, a new album that returned to their original sound and did better commercially than the EP without generating any hits.12Cindy Wilson interview; Jon Piccarella, "The B-52s, Mesopotamia (Warner Brothers)," New York Rocker, April 1982, 43; J. Eddy Ellison, "Athens Own B-52s Rock the Fox, Still Have Their 40 Watt Charisma," Red and Black, May 12, 1982, 2. Of course, the B-52s never played the 40 Watt Club.

Pylon, too, hit a wall. From an underground perspective, the band seemed wildly successful. In Athens, New York, a few other American cities, and in England, they packed the clubs. Elsewhere, audiences did not seem to know what to make of the group. And while the members of Pylon made enough money to live cheaply in Athens, they weren't exactly comfortable. To reach the next level, they hired a professional booking agent. He landed them a gig most bands would have been giddy to get: the opening slot for U2's U.S. tour in support of their recently released album War. At first, band members said no, but eventually they compromised and agreed to play the first several dates. When they took the stage, crowds impatient to see the Irish band ignored them. As Briscoe Hay recalled, "People were heckling . . . 'Where's U2?' and 'Get off the stage.'" What everyone said was great felt instead like failure. It certainly was not fun. Maybe they did not really want this kind of success. Maybe their music was not for everybody. Maybe their performance-art-turned-band was exactly what they said it was, "temporary rock."13Briscoe Hay, interviews; Michael Lachowski, interviews.

In January 1983, Briscoe Hay told the Athens Observer, "I think if it ever became miserable, we would just disband," and in retrospect she was hinting at what was to come. Band members decided around this time to break up at the end of the year, after they fulfilled their bookings, but they kept their decision secret. In Athens, most people found out when posters went up for "Pylon's Last Show" with opening act Love Tractor. The gig took place in a huge venue known more for its cheap drink nights than live music so everyone could come.14Poster reproduced as an ad, Red and Black, December 1, 1983, 6; Lachowski, interviews; Briscoe Hay, interviews.

A live recording of that farewell show released in 2016 finally gave those of us who missed it a chance to listen in on this essential moment in Athens history. From the opening note of the first song, "Working Is No Problem," Pylon lays out what a critic fittingly describes as "an all-business, no-banter set" of twenty-two songs with hair-on-fire intensity that does not let up until the five-song encore finishes. Over the course of approximately an hour and a quarter of music, the crowd roars out its encouragement. Sometimes, the fans sing along to lyrics like "everything is cool" and even occasionally to guitar hooks, like the woo-woo of "M-Train." At other times, they just yell. No one wants the evening to stop. When it does, Pylon ends with a song that only their earliest fans would get and an homage to their origins in Lachowski's loft studio, their version of the Batman theme song. Superheroes fight evil. To resist the way the market strips away every meaning but money, maybe you just have to refuse to play.15Pylon, Pylon Live (Atlanta, GA: Chunklet Industries, 2016); Stuart Berman, "Pylon: Pylon Live," Pitchfork, July 19, 2016, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/22125-pylon-live/.

Interviewed about the breakup, band members reflected on why they had started making music "as another form of artistic expression." "We accomplished what we set out to do," Lachowski said. "It's not that we are miserable, it's just that we've seen all we're going to see and don't want to put any more time into it." "Our whole reason for doing it was for fun," Crowe argued, "and when the fun wears out and it starts turning into a serious type of job—there's no reason to do it anymore." Briscoe Hay captured the purity and the privilege of the band's attitude: "We wanted to do what we wanted to do when we wanted to do it." As Lachowski explained, "What was frustrating was not trying to live like other bands, but trying to convince everybody that we didn't want to do it that way. . . . We were the only ones that understood why we were not out there with the other bands trying to make it big." But for all the talk about fun, at least one band member was still thinking about the importance of form. "We'll become a cult band now," Bewley predicted on the eve of Pylon's last show. "This is a type of suicide that'll make us more popular in the long run." And he was right.16J. Eddy Ellison, "A Found Farewell: Fans, Followers and Friends Sadly Try to Accept," Athens Banner Herald-Athens Daily News, December 2, 1983, 10–11; Lachowski, interviews; Briscoe Hay, interviews; David Pierce, "The Tasty World Interview: Michael Lachowski," Tasty World 2, 23, 29.

It was a tiny crowd really, fewer people than belonged to a single average-sized fraternity. Cline remembered about sixty people plus hangers on, a hundred tops. Briscoe Hay recalled a tight core of about one hundred people. Lachowski, comparing Athens to the early CBGB's days, argued that both scenes were "so vibrant because they were so tight." Proximity and personal relationships were key. Yet closeness alone was not enough. To be a scene, you needed a story. You needed a narrative to connect what was happening in Athens to a larger vision of the good life. You needed a myth.17Mark Cline interviews; Briscoe Hay, interviews; Lachowski, interviews.

With their attention to "form" and their decision to quit at the height of their fame, Pylon provided this story, doing more than any other single group to fuse the loose, downtown-based network of art students, artists, other outsiders, and their friends that the B-52s had helped spark into what became known as the Athens scene. Performing their music, they also shared their bohemian vision. Life should be about making art for and with friends, combining creativity and pleasure and personal relationships, and living within and sharing a culture that you made yourselves. Money and fame were not necessary. They might even be lethal, killing the experience of creative pleasure.

The B-52s had turned pop art and drag into a form of punk music and proved a little bit of bohemia could flower even in as unlikely a location as a Georgia college town. Pylon, too, started with art and ratcheted up the intensity. Performance art depended on presence to offer messy truths. Pylon made performance art people could dance to, delivering a punk comment on the survival of originality in the machine-made future in a southern drawl more commonly associated with the handmade past. Live, the band's raw, intense music worked the contradictory meanings of repetition, how duplicated sounds and acts could evoke expansiveness or constriction, pleasure or boredom, play or work, and the body or the machine. Critics' darlings, repeatedly named the best band in Athens, Pylon carried their art piece so far that they broke up on the cusp of stardom. The members of Pylon might not have had the language to describe resistance to what people by the end of the century would be calling neoliberalism, but they had the sound.

About the Author

Grace Elizabeth Hale is the Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia. Her previous books include A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America and Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940.

Cover Image Attribution:

R.E.M. at the Commodore Ballroom in Vancouver, Canada, June 28, 1984. Photograph by Rob Gander. © Rob Gander.Recommended Resources

Text

Bernard, Gendron. Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Bingham, Shawn Chandler, and Lindsey A. Freeman, eds. The Bohemian South: Creating Countercultures, from Poe to Punk. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Brown, Rodger Lyle. Party Out of Bounds: The B-52's, R.E.M., and the Kids Who Rocked Athens, Georgia, rev. ed. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016.

Lamb, Gordon. Widespread Panic in the Streets of Athens, Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Web

Armstrong, Emily, and Pat Ivers. "Nightclubbing/Pylon." The Local East Village. October 15, 2012. http://localeastvillage.com/2012/10/15/nightclubbing-pylon.

Berman, Stuart. "Pylon: Pylon Live." Pitchfork. July 19, 2016. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/22125-pylon-live.

Hay, Briscoe Vanessa, and Michael Lachowski. "Art Punk Perfection: Deerhunter's Bradford Cox Interviews Pylon." By Bradford Cox. Eldredge ATL. July 1, 2016. https://www.eldredgeatl.com/2016/07/01/art-punk-perfection-deerhunters-bradford-cox-interviews-pylon.

Jean, Kidula, and Susan Thomas. Athens Music Project Oral History Collection. Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries. 2014–. http://russelldoc.galib.uga.edu/russell/view?docId=ead/RBRL379AMP-ead.xml.

McLaughlin, Maureen. "Dancing on the Tables: A Celebration of the Athens-Atlanta Music Scene, Starring the B-52's, the Fans, the Brains, Glenn Phillips and Some Act Named R.E.M.! " Eldredge ATL, July 23, 2016. https://www.eldredgeatl.com/2016/07/23/dancing-on-the-tables-a-celebration-of-the-athens-atlanta-music-scene-starring-the-b-52s-the-fans-the-brains-glenn-phillips-and-some-act-named-r-e-m/.

Nigut, Bill. "'Party Out of Bounds: The B-52s, R.E.M. and the Kids Who Rocked Athens, Georgia' 25 Years Later." GPB News. March 4, 2017. https://www.gpbnews.org/post/party-out-bounds-b-52s-rem-and-kids-who-rocked-athens-georgia-25-years-later.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Bernard Gendron, Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Tricia Henry, "Punk and Avant-Garde Art," Journal of Popular Culture 17, no. 4 (Spring 1984): 30. Another, early node of DIY culture in an unlikely place was the scene which formed in Akron and Cleveland, Ohio, two adjacent and then-deindustrializing cities, after the formation of Devo in 1973. See Calvin C. Rydbom, The Akron Sound: The Heyday of the Midwest Punk Capital (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2018). On the relationship between the Akron scene and Kent State University, see Tim Sommer, "How the Kent State Massacre Helped Give Birth to Punk Rock," Washington Post, May 3, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/how-the-kent-state-massacre-changed-music/2018/05/03/b45ca462-4cb6-11e8-b725-92c89fe3ca4c_story.html. See also the publication D.I.Y: The Do-It-Yourself New Music Magazine, published in Manhattan Beach, California, in 1980 and 1981. Issues included lists of clubs that would book punk and other kinds of new music, independent record stores, and college radio stations, as well as coverage of scenes in Cleveland, New York, Los Angeles, and a few other cities. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Contrast Coran Capshaw, the manager of Charlottesville's most famous musical group, the Dave Matthews Band, with Bertis Downs, R.E.M.'s lawyer and manager, who still runs the business end of that former band. Capshaw is an entrepreneur who runs multiple companies and a real estate empire in the college town where I live now, while Downs spends most of his time as a local and national advocate for public schools. |

| 3. | "Pylon-1980," online at https://vimeo.com/50389377. See also http://localeastvillage.com/2012/10/15/nightclubbing-pylon/, which described the video as part of Pat Ivers and Emily Armstrong's archive of punk-era concert footage being digitized for the Downtown Collection at N.Y.U.'s Fales Library. |

| 4. | Local East Village, "Pylon-1980." |

| 5. | Van Gosse, "Pylon Draws the Line," Village Voice, February 25, 1981, describes Briscoe Hay in a performance at the Rock Lounge in New York on Valentine's Day 1981 as, "shoeless with whistle, in a parochial-school blue smock and white blouse" (3). |

| 6. | Gosse, "Pylon Draws the Line," 3. |

| 7. | "Review of Gyrate," New Music Express, December 1980; Robert Holland, "After Hours," Red and Black, February 8, 1980, 5; "Interview with Danny Beard," Tasty World 3 [April 1985], 11; Jay Watson, "Local Groups Get Boost from DB Records," Red and Black, January 13, 1982, 1, 5; Briscoe Hay, "Vanessa's Version"; Briscoe Hay, interview; Bourne, interview; Biddle, interview; Rasmussen, interview. Bewley did the cover art for the album and former art student Bourne, then working in Atlanta at Beard's record store, did the art direction and design. |

| 8. | Glenn O'Brien, "Glenn O'Brien's BEAT," Interview, March 1981, 62. |

| 9. | Gosse, "Pylon Draws the Line," 61–62. Gosse's article offered very high praise considering how much good rock and roll came out in 1980, including Springsteen's The River, John Lennon's Double Fantasy, Pete Townshend's Empty Glass, David Bowie's Scary Monsters, Grace Jones' Warm Leatherette, Captain Beefheart's Doc at the Radar Station, The English Beat's I Just Can't Stop It, and Stevie Wonder's Hotter Than July, and albums by more underground acts like the Talking Heads' Remain in Light, Elvis Costello's Get Happy!, X's Los Angeles, The Clash's Sandinista!, and the Dead Kennedys' Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables. |

| 10. | Karen Moline, "Pylon: From Athens, GA: New Sounds of the Old South," New York Rocker, March 1981, 15–17; Vic Varney, "'Nineteen Hours from New York': Small Town Makes Good," New York Rocker, March 1981. For more interesting writing about Pylon, see Robert Palmer, "Critics' Choices," New York Times, April 4, 1982; Guy Trebay, "Survey of the Week's Events: Pylon/dB's," Village Voice, April 20, 1982; "Pylon/'Crazy,'" New York Rocker, June 1982, 43; Steve Anderson, "Pylontechnics," Village Voice, November 9, 1982, 66; Stephen Holden, "Music: Pylon at the Ritz," New York Times, May 31, 1983, C15; Tom Carson, "Pylon Up Around the Bend," Village Voice, June 14, 1983, 84; Kim Taylor Bennett, "We Talked to Pylon's Michael Lachowski Because He's a Legend," Vice, August 14, 2014, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/6w3vw6/we-talked-to-michael-lachowski-from-pylon-because-hes-a-legend. |

| 11. | Vanessa Briscoe Hay interviews, T. Patton Biddle interview; Jay Watson, "'Athens' Finest' Play Tonight," Red and Black, January 13, 1982, 5; Moline, "Pylon: From Athens, GA"; T. Patton Biddle, better known as Pat the soundman, has the flyer for the Memorial Hall show with Pylon and Love Tractor on his website at https://www.patthewiz.com/. |

| 12. | Cindy Wilson interview; Jon Piccarella, "The B-52s, Mesopotamia (Warner Brothers)," New York Rocker, April 1982, 43; J. Eddy Ellison, "Athens Own B-52s Rock the Fox, Still Have Their 40 Watt Charisma," Red and Black, May 12, 1982, 2. Of course, the B-52s never played the 40 Watt Club. |

| 13. | Briscoe Hay, interviews; Michael Lachowski, interviews. |

| 14. | Poster reproduced as an ad, Red and Black, December 1, 1983, 6; Lachowski, interviews; Briscoe Hay, interviews. |

| 15. | Pylon, Pylon Live (Atlanta, GA: Chunklet Industries, 2016); Stuart Berman, "Pylon: Pylon Live," Pitchfork, July 19, 2016, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/22125-pylon-live/. |

| 16. | J. Eddy Ellison, "A Found Farewell: Fans, Followers and Friends Sadly Try to Accept," Athens Banner Herald-Athens Daily News, December 2, 1983, 10–11; Lachowski, interviews; Briscoe Hay, interviews; David Pierce, "The Tasty World Interview: Michael Lachowski," Tasty World 2, 23, 29. |

| 17. | Mark Cline interviews; Briscoe Hay, interviews; Lachowski, interviews. |