Overview

As an extended ethnographic account of the GRASSROOTS! performance event in the aftermath of 2012's Hurricane Isaac, this article follows the musicians involved in one corner of the New Orleans rap scene. This piece looks at disaster, recovery, and change through the eyes of rap musicians navigating and performing in the rapidly changing terrain of this post-Katrina city.

Soundings is an ongoing series of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that use historical, ethnographic, musicological, and documentary methods to map and explore southern musics and related practices. This series is guest edited by Grace Elizabeth Hale, Commonwealth Chair of American Studies, professor of history, and director of the American Studies Program at the University of Virginia.

The government blew the levees /

I used that Katrina water to master my flow.—Hollygrove Mikey, "Make Medicine Sick"1"Hollygrove Mikey, The Ca$hius Clay Tape," http://hollygrovemikey.bandcamp.com/.

|  | |

| Lil Wayne plays the guitar, Washington, DC, January 15, 2008. Photograph by Flickr user Georgetown Voice. Courtsey of Georgetown Voice, Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0. | Big Freedia at Bootleg Theater, Los Angeles, California, January 26, 2012. Photograph by Flickr user Mikey Walley. Courtesy of Mikey Wally, Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0. |

New Orleans rap is everywhere and nowhere. Lil Wayne reigns as a global superstar. Big Freedia is a critical darling of bounce, New Orleans's dance-centric rap genre. Cash Money bling remains lodged in the pop culture psyche while Young Money, though now more closely associated with Miami than New Orleans, entertains a new generation. New Orleans bounce twerking became a mainstream topic in 2013 via Miley Cyrus's controversial career reinvention.2Nico Lang, "Cultural Appropriation Is a Bigger Problem than Miley Cyrus," Thought Catalog, August 26, 2013, http://thoughtcatalog.com/nico-lang/2013/08/cultural-appropriation-is-a-bigger-problem-than-miley-cyrus/. For Big Freedia's response to Miley Cyrus, see Jason Newman, "Bounce Queen Big Freedia Slams Miley Cyrus' Twerking," FUSE TV, August 18, 2013, http://www.fuse.tv/2013/08/big-freedia-miley-cyrus-twerk. Two archival projects have brought further attention to New Orleans rap: the Where They At bounce exhibit by Alison Fensterstock and Aubrey Edwards,3Archival photographs and audio excerpts of accompanying oral history interviews can be found at "Where They At," http://wheretheyatnola.com/. which was featured at the Smithsonian-affiliated Ogden Museum of Southern Art in 2010, and the NOLA Hip-Hop Archive, which I founded in 2012 and is housed at the Amistad Research Center.4The NOLA Hip-Hop Archive is the first university-affiliated rap archive in the Deep South: "NOLA Hip-hop Archive," http://www.nolahiphoparchive.com. The Amistad Research Center is the nation's oldest, largest, and most comprehensive independent archive specializing in African American history: "Amistad Research Center," http://www.amistadresearchcenter.org. Greater interest in New Orleans rap and bounce post-Katrina, with increased attention to the musical styles' connections to the city's rich history of African American expressive culture,5Matt Miller, Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 172. has resulted in a slow but steady incoming stream of writers and filmmakers to document the scene. And yet New Orleans rap has remained, in important ways, marginal within the city's dominant culture: limited in venue bookings, performance opportunities, and insurance for events;6This is one of many recurrent themes taken from my interviews with artists for the NOLA Hip-hop Archive. under-studied by scholars;7A notable exception is the spate of scholarly work on New Orleans "sissy bounce" and gender politics. Two recent monographs engaging with mainstream rap and bounce in New Orleans are Matt Sakakeeny, Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013) and Miller, Bounce. and covered by only a handful of local writers.8Notable exceptions include the work of writers Alison Fensterstock (Times-Picayune), Alex Woodward (The Gambit), Keith Spera (Times-Picayune), Scott Aiges (Times-Picayune, New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival and Foundation) and Ned Sublette, The Year Before the Flood: A Story of New Orleans (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2009). Writing in 2006, New York Times contributor Kelefa Sanneh argued that the snubbing of New Orleans rap appeared exceptional, particularly in light of the fact that rap as a genre had gained increasingly undisputed institutional and cultural validation elsewhere in the country.9Kelefa Sanneh, "New Orleans Hip-Hop Is the Home of Gangsta Gumbo," New York Times, April 23, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/arts/music/23sann.html. But while the tension between the ubiquity and invisibility of New Orleans rap remains a continued reality, the precarity of rap in the city has undergone a noticeable shift since the time of Sanneh's writing. There has been a visible increase in rap and bounce bookings for local festivals,10French Quarter Fest is one of many local festivals that has shown a noticeable increase in local rap and bounce bookings. Jazz Fest includes more rap and bounce artists in their Allison Miner Music Heritage Stage programming, in particular. for example, and bounce, in particular, is showing signs of a full-blown revival.11Holly Hobbs and Alison Fensterstock, "New Orleans Hiphop and Bounce Storytelling, Preservation, and Place in Post-Katrina" (paper presented at the Music of the South conference, Oxford, Mississippi, April 2–3, 2014). New Orleans's famed jazz venue, Preservation Hall, began booking rap and bounce artists for the first time in 2013 with DJ Jubilee,12Alison Fensterstock, "DJ Jubilee Makes History with Acoustic Bounce Show at Preservation Hall," Nola.com, November 9, 2013, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2013/11/dj_jubilee_makes_history_with.html. followed by former No Limit recording artist Fiend and producer Nesby Phips.13Alison Fensterstock, "PressHall Brass Backed Fiend and Nesby Phips for a Wild Midnight Show at Preservation Hall," Nola.com, March 2, 2015, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2015/03/preshall_brass_backed_rappers.html. Back in 2003, DJ Davis Rogan was (in)famously fired for, among other things, playing local rap on New Orleans's listener-supported community radio station, WWOZ 90.7FM.14See Scott Jordan, "The Rap on WWOZ," The Gambit, August 19, 2003, http://www.bestofneworleans.com/gambit/the-rap-on-wwoz/Content?oid=1241861. Rogan was an inspiration for Steve Zahn's DJ Davis McAlary character in David Simon's Tremé on HBO. While there are two commercial hip-hop/R&B radio stations in New Orleans at the time of writing—93.3FM and 102.9FM—both must abide by regulations set by the stations' corporate parents limiting local rap and bounce play, though both have made important advances in getting local rap on the air. See 93.3FM radio star Wild Wayne's oral history interview at http://www.nolahiphoparchive.com. Today, WWOZ's official policies regard rap and bounce as part of the New Orleans music canon, and WWOZ employees were instrumental in the release of B Is for Bounce, the first vinyl LP reissue of bounce artist Ricky B's15Ricky B, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, July 7, 2012, http://www.louisianadigitallibrary.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16313coll68/id/117/rec/39. classic local hits.16Alison Fensterstock, "Bounce Originator Ricky B Celebrates Album Release at Blue Nile April 5, along with the Stooges Brass Band," Nola.com, April 2, 2013, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2013/04/bounce_originator_ricky_b_cele.html. Actual airplay for New Orleans rap and bounce on WWOZ, however, remains minimal. "Katrina wiped the palette clean in New Orleans," says Nesby Phips, New Orleans rapper/producer and grand-nephew of Mahalia Jackson. "It ushered in a new era of music, musicians, and perspectives. But the sound is diluted now. And we've lost the original players. Some things are better, other things are worse."17Nesby Phips, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, July 13, 2014, http://www.louisianadigitallibrary.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16313coll68/id/117/rec/39.

|

| Table at GRASSROOTS!, New Orleans, Louisiana. Photograph by Larry Legaux. Courtesy of Larry Legaux. |

While it is clear that the status of rap in the New Orleans public imagination is shifting, as evidenced by increased festival bookings, a wider array of opportunities across the board, and the movement of rap into historically non-rap spaces (the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Tulane University Digital Library, the Amistad Research Center, Preservation Hall, WWOZ, and so on), on-the-ground realities for most rappers in the city remain slow to change. Despite its takeover of the charts in recent years, southern rap in general––especially the musical output of particularly marked underclass communities—continues to fight for credibility and change under a low ceiling of critical respectability.18See, among others, Insanul Ahmed, "Hate of the Union: When New York Disses The South,"Complex Magazine, July 1, 2010, http://www.complex.com/music/2010/07/hate-of-the-union-when-new-york-disses-the-south/; Darren E. Grem, "'The South Got Something to Say': Atlanta's Dirty South and the Southernization of Hip-hop America,"Southern Cultures 12, no. 4 (2006): 55–73; Ali Colleen Neff, Let the World Listen Right: The Mississippi Delta Hip-Hop Story (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2009); Roni Sarig, Third Coast: OutKast, Timbaland, and How Hip-Hop Became a Southern Thing (New York: Da Capo Press, 2007); and Ben Westhoff, Dirty South: OutKast, Lil Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern Rappers Who Reinvented Hip-hop (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011). Key is how this relates to an artistic dedication to an underclass sensibility untranslatable to the mainstream, for which New Orleans (and its microcosms) has often functioned as a symbolic center.19Travel writers and scholars have long characterized New Orleans as the most African of US cities, see Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, "The Formation of Afro-Creole Culture," in Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization, ed. Arnold R. Hirsch et al. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992), 58–87. Anthropologist Melville Herskovits argued that "those aspects of the African tradition peculiar to this specialized region have reached their greatest development [in New Orleans]" in The Myth of the Negro Past (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1941), 245. If, as Congolese scholar V. Y. Mudimbe has written, the representational function of Africa operates as a "sign of something else," then New Orleans, fetishized, exoticized, and romanticized ad nauseum, is a "sign of something else" writ large in the American psyche. See The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1988), ix. For an extended discussion of these dynamics, see Lewis Watts and Eric Porter, New Orleans Suite: Music and Culture in Transition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 5. As mass mediated images of Katrina "refugees" have informed much of the world's knowledge of black New Orleanians, these paradigms have become even more pronounced. See Zenia Kish, "Hiphop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora," American Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2009): 671–692. Writing about the systemic precarities of New Orleans rap and bounce artists requires thinking about multiple histories, as well as the cross-racial and cross-class desires that, as Lewis Watts and Eric Porter put it, cherish traditional culture bearers in a tourist economy while simultaneously ignoring or breeding hostility toward those members of poor communities of color not engaged in more "accepted" forms of cultural work.20Watts and Porter, New Orleans Suite, 7. See also Sakakeeny's discussion of New Orleans musicians and the tourism economy in Roll With It, 69–107. Ethnographic studies of New Orleans rap and bounce can still be counted on one hand.21See Nik Cohn, Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007); Daron Crawford and Pernell Russell, Beyond the Bricks, (New Orleans: Neighborhood Story Project, 2009); Miller, Bounce; and Sakakeeny, Roll With It, along with the work of journalists mentioned in note 8. In what follows, I provide an extended ethnographic introduction to one corner of the New Orleans rap scene in order to better understand the ways in which some musicians are navigating the post-Katrina city.

GRASSROOTS!

|

| Truth Universal at the Congo Square Festival, New Orleans, March 24, 2013. Photograph by Holly Hobbs. Courtesy of Holly Hobbs. |

Led by New Orleans emcee Truth Universal and developed and supported by youth with limited resources, the GRASSROOTS!22Capitalization derived from Truth Universal's preferred marketing of the event. monthly performance event was held from February 2002 until December 2012, with a year-long, post-Katrina hiatus.23GRASSROOTS! was begun by Truth Universal in 2002 at the Neighborhood Gallery Theater on Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in the Central City neighborhood of New Orleans. At that time, the Neighborhood Gallery was a vital part of the city's black community-based business network. Begun by Sandra Berry and Joshua Walker in their living room on Soniat Street, the Neighborhood Gallery permanently closed after Hurricane Katrina. Truth relocated GRASSROOTS! to the Dragon's Den in 2007, where it remained until its final show in December of 2012. The ongoing effects of natural and man-made disasters and the institutionalized structural inequities that give rise to violence, premature death, and foreclosed life chances are a constant strain on many of New Orleans's rap publics. My account describes one of the final GRASSROOTS! events, in the wake of 2012's Hurricane Isaac, as a site of power, critique, mediation, and healing. As Zenia Kish notes in "My FEMA People," post-Katrina rap was instrumental in asserting a politics of voice against a regime of representation in which "black and poor suffering bodies were everywhere seen, but very rarely heard from."24Kish, "Hiphop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora," 672. Now nearly a decade removed from Katrina, the explicit resistance politics in New Orleans rap and bounce songs in the immediate aftermath of the storm25See Kish, "Hiphop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora," for a detailed account of post-Katrina rap and activism. have broadened into a general politics of vigilance, with many artists working to link their struggles with those of other activist groups both in New Orleans and throughout the world. I offer here an ethnographic introduction to New Orleans rap as cultural production that continues to work to stabilize sites of disaster.26Representation is always a fraught proposition. Visit the NOLA Hip-hop Archive to hear artists speak about the complexity of representation in their own words.

|

| Dee-1 with his mother, New Orleans, Louisiana, April 25, 2014. Photograph by Flickr user kowarski. Courtesy of kowarski, Creative Commons License CC-BY 2.0. |

It's Saturday night in New Orleans.27The ethnographic moment presented here is an excerpt from my forthcoming dissertation, "'Shake Fo' Ya Hood': Hip-Hop and Recovery in Post-Katrina New Orleans." The first day of September 2012 has arrived in usual fashion, with people breathing an audible sigh that the oppressively hot summer will soon come to a close. I drive down Claiborne Avenue from my house uptown, attempting to bypass the French Quarter, where sirens are blaring. There's debris and trash along the road and the night is dark and eerily still, as it always is after a storm. Hurricane Isaac has just hit South Louisiana on the anniversary of the terrible storm that changed the city and the Gulf South.

Hundreds of thousands of residents of South Louisiana have been without power for the duration of Isaac. The final tally would count nearly 59,000 homes damaged.28"Hurricane Isaac Damaged 59,000 Homes in Louisiana, Officials Estimate," Associated Press, September 28, 2012, http://www.nola.com/hurricane/index.ssf/2012/09/hurricane_isaac_damaged_59000.html. Experts talk about the changes to the levee system using terms like "cost-benefit analysis."29John Schwartz and Campbell Robertson, "New Orleans Levees Hold, and Outsiders Want In," New York Times, September 6, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/07/us/new-orleans-levees-hold-and-outsiders-want-in.html. In this post-Katrina world, the levees protect the city of New Orleans more securely, but increase the risk of damage to surrounding coastal areas.30Bob Marshall, "Hurricane Isaac Lays Bare the Painful Economics of Flood Protection," The Lens, September 2, 2012, http://www.nola.com/hurricane/index.ssf/2012/09/hurricane_isaac_lays_bare_the.html. This time, New Orleans has escaped relatively unscathed, and the calls people place to their families and loved ones as phones begin to work again have allowed everyone to breathe normally for the first time in a week. Outside the city, mandatory evacuations forced many to leave their homes while others who chose not to leave, or could not, were forced into boats and attics. The parents of New Orleans rapper Dee-1 relocated to the small community of LaPlace after Hurricane Katrina, believing they would be safer there than in New Orleans. Dee-1 tried to get in touch with his parents during the storm, only to find out that they had been trapped in the attic of their house for days before being rescued by boat.31KVLE, "Studio Life: How Dee-1's Parents Were Saved," 3 Little Digs, September 3, 2012, http://3littledigs.com/blog/2012/09/03/studio-life-dee-1/. Dee-1 remembers,

Hurricane Isaac, that stuff, that stuff really . . . that stuff was unexpected. My parents lost their house, they lost both of their cars. I could just tell that, you know they staying strong as they can but I could just tell, it did something to them. It reminds me of how my grandparents felt after Katrina, you know. My grandpa took Katrina so hard, like personally took it hard, and you know, my parents, they taking this kind of hard. They staying optimistic as much as they can, though. And they . . . they . . . they are . . . trying their best to shake back from it. They lost their crib, lost all the contents inside, and they were trapped. And that was like a real stressful day for me because I was in Atlanta when the storm hit. I left. And I asked anybody if they wanted to come and everybody was like nah, we're good, we're gonna stay here, this is not gonna be a big deal. So I was like aight, cool. I was more worried about my grandparents than my parents, cuz my grandparents still live in the East. And when I found out from my little sister that my parents' house was flooding and that they were trapped inside, yeah, that stuff . . . I had to really come to grips with . . . I had to really rationalize the thought that my parents might die, you know, they might die today. And it's not like you just get bad news and you hear it unexpectedly, I had to become content with that thought because I for so long I couldn't get in touch with them and all I knew was that flood water was rising and they were still in that house. And I'm so far away. So. Um. It actually ended up being a blessing though, cuz it showed me how many people really care . . . a lot of people came to my assistance, either prayed or personally wished me well or actively did something to help them get rescued. So Hurricane Isaac is yet another chapter in the saga of this life that I'm living right now. You know. It's just another chapter, man.32Dee-1, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, September 15, 2012, http://cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p16313coll68/id/4/rec/9.

The stoplights aren't working as I drive down Esplanade Avenue, its grand old buildings only visible in shadowed relief. I'm in the Marigny neighborhood, adjacent to the French Quarter and backed by the Bywater and the Lower 9th Ward. For a Saturday night, I find a parking place easily and make the short walk to the Dragon's Den, the venue of GRASSROOTS! since its post-Katrina return in 2007. Most people have been without electricity in ninety-five-degree heat for a week, and we look it. It's after ten, early by New Orleans standards––and it'll be another hour before people start trickling in the door.

|

| The Dragon's Den, New Orleans, Louisiana. Photograph by Holly Hobbs. Courtesy of Holly Hobbs. |

Hazy red light from paper lanterns strung over the Dragon's Den bar shines through the windows out onto the near-empty street. The brick building, dating to 1862,33The earliest act of sale for the building dates to 1882, although according to the Bourbon Group, the building was likely built twenty years before that date. was originally a family residence built on a plot of land once referred to as Esplanade Ridge.34Mary Louise Christovich, Sally Kittredge Evans, and Roulhac Toledano, New Orleans Architecture: The Esplanade Ridge (New Orleans: Pelican Publishing, 1995), 18. Its two stories are covered with creeping ivy and a second floor balcony with colonial ironwork remains closed these days, sagging under weight and time. A narrow corridor leads to an open-air courtyard and an even narrower stairway that winds its way up to the second floor, where the booming bass of an EDM show echoes down the stairs and spills out onto the street below. Tonight GRASSROOTS! is being held downstairs, where a small bar turns a profit slinging drinks to show-goers and tourists who amble in from adjacent Frenchman Street. The evening's DJ, New Orleans-born/Houston-raised Jay Skillz, is busily setting up equipment on the small stage while Truth Universal assembles his merch table, carefully folding t-shirts and setting out CDs.

Truth Universal, born Damian Tudor in Trinidad, moved as a child with his family to New Orleans in the late 1970s. People have been coming and going between New Orleans and the Caribbean for centuries, but Truth wouldn't think much about that until later, when he began to write poetry. Growing up in the downtown 7th Ward neighborhood and New Orleans East, he came to music with dreams of being a DJ. After school, he and friends would rush to the house of the only friend in the neighborhood who could afford a turntable. There, they spent many hours practicing, telling stories, and going through records. After early encouragement and a few successful informal performances in college, Truth decided to pursue a career as an emcee. Over the next few years, he built a small following and a reputation as a talented performer and community activist. His career has flourished over the last decade, featuring performances with internationally recognized acts such as The Roots, Mos Def, Afrika Bambaata, Talib Kweli, and Alanis Morisette. Although signed to national labels Dragon's Breath and Guerilla Funk, with Atlantic briefly expressing interest, Truth is far better recognized as a New Orleans hip-hop community leader.35Alex Woodward, "Truth Universal Discusses His New Album and Politics in Hip-hop," The Gambit, September 10, 2013, http://www.bestofneworleans.com/gambit/universal-appeal/Content?oid=2250160. Music writers label him "conscious hip-hop," but Truth's music is a lot of other things, too. Over the course of his career, Truth feels that the "conscious" label has tended to prove limiting. On this Saturday night in September, Truth hangs his banner across the edge of his merch table and looks at his watch.

The Dragon's Den sits at the tourist crossroads of Frenchman Street and Esplanade. It is not a local African American neighborhood space—all the rappers who perform at GRASSROOTS! have traveled from other parts of the city to get here. On a normal evening, DJs, EDM kids, ravers, tourists, Rastas selling jewelry, students, and itinerants wander through the space next to men cooking oysters and meats on makeshift grills. But tonight is quiet. Lyrikill from Delhi, Louisiana, in Richland Parish, is the featured artist for the evening. He relocated to Houston earlier in 2012 but made the six-hour drive back to New Orleans tonight. He stands with friends and other rappers in the courtyard, wondering if he will have anyone to perform for. Unlike second lines or jazz funerals, or even a few blocks away on St. Claude Avenue for the "sissy bounce"36I use quotes to denote widespread ambivalence about the use of the term. shows of the early 2010s,37"The Urbanist's New Orleans: What To Do," New York Magazine, April 1, 2012, http://nymag.com/travel/features/new-orleans-entertainment-2012-4/. there are no journalists at the Dragon's Den tonight. I'm taking notes about the show but I'm also working the door, as my duties with Truth Universal over the years have included manager, friend, and promoter. About half of the people who come through complain about the $5 cover.

DJ Jay Skillz has started the night with a set of southern rap mixed with radio hits of the month, transitioning adeptly from "Burn" by hot-rapper-du-jour Meek Mill into "Damn!" by Atlanta-based rappers YoungBloodZ, featuring Lil Jon. By 11:15 pm, Truth gets on the mic and announces that he's about to start the show. The crowd is disappointingly small, and Truth laments the fact that the hurricane has kept people away. He makes the decision to stop charging at the door, hoping to get a better crowd. After a few more minutes, Truth moves through the audience and takes the stage, and with his trademark baritone says, "It's GRASSROOTS!" The crowd, well-versed in this familiar call-and-response, responds, "It's GRASSROOTS! Let's go."

|

| Rapper Asim, New Orleans, Louisiana. Photograph by Stefan Henry. |

Asim is up first, a rapper with long dreads wearing headphones over a stocking cap, despite the ninety-degree night air and oppressive humidity. Raised in Virginia and California, Asim moved to New Orleans in 2009, where he says he found the poetic community he had been seeking. For many here, rap creates a sense of place realized through participatory performance. Tonight, Asim has given the DJ a jump drive with three of his tracks, and he quickly takes the stage and launches into the first––a heavy, fuzzed-out bass line under a looped melody over which he raps in rapid-fire time.

Sample from Asim, "Keep Light Moving," 2015.

Dream of being kings but we are driven to floss

Bling rings, sell drugs and wind up in Sing Sing

All for the attention and fame these things bring

Gotta keep light moving . . .

After his performance, I ask him why he'd chosen the tracks he did. Asim replied, "I wanted to get loud tonight. A lot of stuff has happened this week. I wanted to get loud."

Asim's pensive songs often center around the lures of hustling, but his lyrics tonight are not nearly as important to him as demanding attention through sheer sound—a reminder that placing an emphasis on lyrical analysis can discount the ways in which voice and sound have the ability to produce self and community identity within the deep, polyrhythmic framework of southern hip-hop bass.

Truth claps for Asim and announces that due to the storm, several of the other booked performers won't make it. Truth usually books one to two headliners and leaves spots available for four to seven other performers, ensuring that the performance platform works for as many artists as possible each month. Those who aren't able to perform usually remain afterward for an informal free-style session. As Asim exits the stage, Jay Skillz cues Truth's song, "Serve and Protect," and Truth goes into one of the crowd's favorites:

Sample from Truth Universal, "Serve & Protect," Dragons Breath Records, 2008.

People hate police all over the planet,

property of the rich they protect and manage

violence and repression, only things they respect,

they serve, protect, and break your fuckin' neck . . .

|

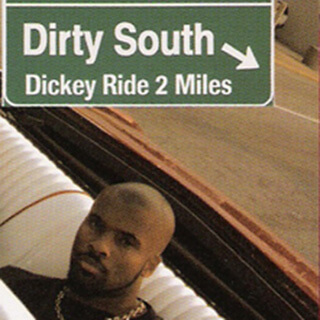

| GRASSROOTS! flyer advertising September 1, 2012 show with Lyrikill and Elespee. |

The song, produced by an artist named NO Bricks, samples Willie Hutch's 1974 "Theme of Foxy Brown." Many performers here tonight will use beats heavily laden with samples from the African American soundscape of the 1970s, an aesthetic George Lipsitz has termed "the long fetch of history"38George Lipsitz, "Introduction: The Long Fetch of History; or, Why Music Matters," in Footsteps in the Dark: The Hidden Histories of Popular Music (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), vii–xxv. in his discussion of the deep cultural resonance of songs and eras that reflect pivotal historical and cultural change. Lyrically, Truth uses the collective first-person to critique police brutality in "Serve and Protect" as a strategic tool to connect the local experience to that of the greater Black Atlantic.

Rapper Elespee, a towering figure with kind eyes, performs next. He's part of a loosely organized music production crew along with a producer named Prospek and rapper Impulss, an artist from Michoud, Louisiana—located at the very edge of the Ninth Ward built on what was once a sugar plantation. Years ago, Impulss was in talks to sign to Def Jam South, but a series of contentious meetings and disagreements about how he should be marketed landed him back in New Orleans, where he continues to record and perform.39Impulss, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, June 4, 2012, http://cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p16313coll68/id/14/rec/22. Tonight Elespee performs alone, fighting back sweat and displaying a commanding presence onstage. Tonight, Prospek makes his beats, an artist who has made a name for himself as an innovative hip-hop producer in a city full of independent musicians. Elespee's songs are rich with old soul samples and a 1970s aesthetic that the rapper matches in his own style.

Sample from Elespee, "Crescent City Sunrise," the Trip EP. Produced by Prospek, 2012.

Word to Ricky B,

They still 'Shakin' For They Hood'

Hollygrove, Uptown, Brick City to Inglewood,

Where all they ever wanted was a little leather and wood

And to occupy the space where fallen stars once stood . . .

Here, the bounce-music convention of calling out neighborhoods and wards through song, highlighted through the reference to bounce legend Ricky B's classic track, works within a lyrical framework that purposefully connects New Orleans (Hollygrove, Uptown) to New Jersey (Brick City) and Inglewood (California). The repeating two minor chords in the beat underscore the song's memorial for the things, places, and people that have been lost or forever altered. Elespee's performance takes on deeper meaning for a crowd that has just suffered through a week of uncertainty and stress at the hands of the storm.

Although there are no female performers here tonight (there often are), and despite the seemingly hypermasculine setting, women's participation is central to musical performance here. Female audience members' speech and verbal skill feature prominently in the evening's tenor, and one woman will later compete in the late-night freestyle session after the formal close of the show. To date, researchers have largely ignored women's integral roles in New Orleans rap as writers, performers, dancers, audience members, producers, and facilitators.40The writing of Alison Fensterstock, Matt Miller's work on Mia X, and Zenia Kish are notable exceptions to the erasure of women in New Orleans rap.

|

| Rapper Lyrikill, New Orleans, Louisiana, September 1, 2012. Photograph by Larry Legaux. Courtesy of Larry Legaux. |

Some time after midnight, Lyrikill balances on the edge of the stage, waiting to perform. From upstairs, we can hear a dubstep DJ's bass rattling the venue's ancient windows, making everything buzz dully on the downbeat. Since we stopped charging some time earlier, a few young people from upstairs trickle in, and while they're unfamiliar with the artists, Lyrikill is grateful he doesn't have to perform to an empty room. Minutes before he starts, a small crowd of regulars begins to appear, along with a few newcomers, some standing at the bar or hanging out by the stage, others taking up positions at Dragon's Den's few uncomfortable chairs and tables. Lyrikill grins and grabs the mic to lead the audience in a hurricane-inspired call–and–response:

"Fuck Isaac!"

The crowd yells back "Fuck Isaac!"

Lyrikill launches into his set, moving quickly through some of his better-known songs, "This Moment" and "I Am That Dude," singing, "I got to see heaven / I seen hell already." "Yes Inf**kingdeed,"41David Dennis, "Lyrikill—'Yes Inf**kingdeed' Video," The Smoking Section, August 30, 2011, http://uproxx.com/smokingsection/2011/08/lyrikill-yes-infkindeed-video/. is one of his biggest songs to date, but he soon realizes that he's only brought the finished version of the song and not an instrumental-only show disc. He makes a preemptive joke on the mic, knowing that this insider rap crowd will ridicule his performing over backing vocals. The minimalist beat of "Yes Inf**kingdeed" centers around two sustained organ chords (a minor tonic [i] and major supertonic [II]) created by producer Prospek to compliment Lyrikill's slow drawl:

Sample from Lyrikill, "Yes Inf**kingdeed," More Heart More Sole, by Elevated Minds Music Group, 2011.

Once the lights get low, a pro show rocker

Flow so proper, just have all of my dollars,

I'ma hang around and holla, ain't frontin' like no baller,

I'ma take your girl number, I know I'll never call her

Ain't turnin' down nothin' but my collar . . .

Truth climbs onstage with him to perform "The GRASSROOTS! Campaign" to close out the show:

Sample from Truth Universal, "The GRASSROOTS! Campaign," Guerilla Business, by Root70Lounge, 2010.

Breathe to this, bleed to this

or concede revolutionary seeds to this

The shrill violin from the NO Bricks-made Electric Light Orchestra's "Livin' Thing" sample pushes the bars forward into a frenetic pace. Everyone's adrenaline and emotion is in the air, vibrating with an intensity that Truth and Lyrikill sense from the stage and incorporate into the show. Tricia Rose put it most simply: "Hip-hop gives voice to the tensions and contradictions in the public urban landscape during a period of substantial transformation . . . and attempts to seize the shifting urban terrain, to make it work on behalf of the dispossessed."42Tricia Rose, "A Style Nobody Can Deal With: Politics, Style and the Postindustrial City in Hip Hop," in Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture, ed. Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose (New York: Routledge, 1994), 72. But at times like these, it is clear that acts of performance don't simply mirror real life or social reality, but they actively create them.43See Kelly M. Askew, Performing the Nation: Swahili Music and Cultural Politics in Tanzania (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 23.

Sometime after 1:00 am, Truth closes the show with the GRASSROOTS! call-and-response. Jay Skillz is putting beats in a queue to play for the rappers lining up to participate in a freestyle session. I count the money—seventy dollars—and hand it to Truth at his merch table, selling t-shirts made by the GRASSROOTS! and New Orleans Soundclash beat battle organizers that read "Hip-hop Is Alive!".

|

| Merchandise table at a GRASSROOTS! event, New Orleans, Louisiana, September 1, 2012. Photograph by Holly Hobbs. Courtesy of Holly Hobbs. |

Tonight's performances have all emphasized intense locality, what Murray Forman has termed the "extreme local" sensibilities of contemporary rap44Murray Forman, The 'Hood Comes First: Race, Space and Place in Rap and Hip-Hop (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2002), xvii. and what Matt Miller has called the "stubbornly and self-consciously local approach that runs throughout the history of rap in [New Orleans]."45Miller, Bounce, 1. As is generally true in local rap and bounce performances, the artists here tonight name-checked their ward/neighborhood and referenced sounds and lyrical conventions of foundational songs in the New Orleans rap canon. The artists also reframed their performances to reference Hurricane Isaac, which in turn metonymically referenced Katrina. Natural, environmental, and man-made disasters in New Orleans have caused ongoing rupture, loss, and displacement. Socio-historical disasters have created racialized, institutionalized poverty, geospatial marginalization, and violence. Most musicians here tonight have lost friends, family, places, possessions, and touchstones that ground the human experience. But, in Marcyliena Morgan's words, "hiphop redraws the urban grid and transforms ideal spaces into problematic ones and decaying spaces into fertile, creative landscapes."46Marcyliena Morgan, The Real Hip-hop: Battling for Knowledge, Power and Respect in the LA Underground (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 5. In this context, and through a plurality of positions and perspectives, rap performance is doing the important work of both producing and stabilizing self, community, and place, creating a safe, creative space to redraw boundaries and renegotiate power.

After Ward

The day following GRASSROOTS! is a sunny Sunday, September 2, 2012. The annual Hurricane Katrina commemoration and second line has begun in the Lower 9th Ward.47The event had been rescheduled from its usual August 29th date due to Hurricane Isaac. The second line is led by New Orleans 9th Ward-native rapper and activist Sess 4-5, who grew up in the Desire housing project, and members of The Stooges brass band. Although not yet noon, it is blisteringly hot. I feel for the sousaphone player, already sweating under the weight of his instrument. The marchers cross the bridge and pass the Dollar General on the right, making the turn to end the second line at Bunny Friend Park for an all-afternoon event featuring Partners-n-Crime, Choppa, Keedy Black, 8-9 Boyz, Iris P, 10th Ward Buck, 5th Ward Weebie, Hot 8 brass band, Free Agents brass band, and Truth Universal.

GRASSROOTS! had now entered into its final days as a monthly event, with only two more shows before the final one in December 2012, marking the end of a decade of the city's longest running monthly hip-hop performance platform.48Alison Fensterstock, "December 1 Edition of Truth Universal's 'Grassroots' Will Be Hip-hop Showcase's Last Monthly Event," Nola.com, November 30, 2012, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2012/11/dec_1_edition_of_truth_univers.html. After the Katrina commemoration, I ask Truth Universal how he feels. "Tired," he says, and laughs. "I just look at how the event influenced the way people operate. I see Marcel P. Black, Slangston, Lyriqs, A. Levy—cats involved with GRASSROOTS! heavy over the last few years. They do their own events now, but not just for themselves. They're sharing with the people they host. I'm proud of that. Seems like maybe all this has done something."

About the Author

Holly Hobbs is a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology at Tulane and the founder/director of the NOLA Hip-Hop Archive, a digital archive of hip-hop oral histories housed at New Orleans's Amistad Research Center. Hobbs has researched and written on grassroots music traditions in the American South, the west of Ireland, and East Africa. She currently writes for KnowLA: the online encyclopedia of Louisiana Music and Culture, Music Rising, UNESCO's Collection of Traditional Music via Smithsonian Folkways, and the urban music and culture website, The Smoking Section.

Recommended Resources

Audio

Asim. #StreetCornerJunkiezPushingProse. Released February 10, 2013. http://asimterasu.bandcamp.com/album/streetcornerjunkiezpushingprose.

Elespee. The Trip EP. Produced by Prospek. Released September 14, 2010. © by Guerilla Publishing Company. http://thegpc.bandcamp.com/album/the-trip-e-p.

Lyrikill. More Heart More Sole. Released July 26, 2011. © by Elevated Minds Music Group. http://lyrikill.bandcamp.com/album/more-heart-more-sole.

Truth Universal. Self Determination. Released April 8, 2008. © by Dragon's Breath. https://truthuniversal.bandcamp.com/album/self-determination.

———. Guerilla Business. Released May 4, 2010. © by Root70Lounge. http://www.undergroundhiphop.com/truth-universal-guerrilla-business/R70TU02CD/.

Text

Dyson, Michael Eric. Come Hell or High Water: Hurricane Katrina and the Color of Disaster. New York: Basic Civitas, 2006.

Miller, Matt. Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

Sakakeeny, Matt. Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

Web

Fensterstock, Alison and Aubrey Edwards. "Where They At: New Orleans Hip-Hop and Bounce in Words and Pictures." http://www.wheretheyatnola.com/.

"Neighborhood Story Project." University of New Orleans. http://www.neighborhoodstoryproject.org/.

Tulane University Digital Library. "NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive." Tulane University. http://www.nolahiphoparchive.com.

Similar Publications

| 1. | "Hollygrove Mikey, The Ca$hius Clay Tape," http://hollygrovemikey.bandcamp.com/. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Nico Lang, "Cultural Appropriation Is a Bigger Problem than Miley Cyrus," Thought Catalog, August 26, 2013, http://thoughtcatalog.com/nico-lang/2013/08/cultural-appropriation-is-a-bigger-problem-than-miley-cyrus/. For Big Freedia's response to Miley Cyrus, see Jason Newman, "Bounce Queen Big Freedia Slams Miley Cyrus' Twerking," FUSE TV, August 18, 2013, http://www.fuse.tv/2013/08/big-freedia-miley-cyrus-twerk. |

| 3. | Archival photographs and audio excerpts of accompanying oral history interviews can be found at "Where They At," http://wheretheyatnola.com/. |

| 4. | The NOLA Hip-Hop Archive is the first university-affiliated rap archive in the Deep South: "NOLA Hip-hop Archive," http://www.nolahiphoparchive.com. The Amistad Research Center is the nation's oldest, largest, and most comprehensive independent archive specializing in African American history: "Amistad Research Center," http://www.amistadresearchcenter.org. |

| 5. | Matt Miller, Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 172. |

| 6. | This is one of many recurrent themes taken from my interviews with artists for the NOLA Hip-hop Archive. |

| 7. | A notable exception is the spate of scholarly work on New Orleans "sissy bounce" and gender politics. Two recent monographs engaging with mainstream rap and bounce in New Orleans are Matt Sakakeeny, Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013) and Miller, Bounce. |

| 8. | Notable exceptions include the work of writers Alison Fensterstock (Times-Picayune), Alex Woodward (The Gambit), Keith Spera (Times-Picayune), Scott Aiges (Times-Picayune, New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival and Foundation) and Ned Sublette, The Year Before the Flood: A Story of New Orleans (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2009). |

| 9. | Kelefa Sanneh, "New Orleans Hip-Hop Is the Home of Gangsta Gumbo," New York Times, April 23, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/arts/music/23sann.html. |

| 10. | French Quarter Fest is one of many local festivals that has shown a noticeable increase in local rap and bounce bookings. Jazz Fest includes more rap and bounce artists in their Allison Miner Music Heritage Stage programming, in particular. |

| 11. | Holly Hobbs and Alison Fensterstock, "New Orleans Hiphop and Bounce Storytelling, Preservation, and Place in Post-Katrina" (paper presented at the Music of the South conference, Oxford, Mississippi, April 2–3, 2014). |

| 12. | Alison Fensterstock, "DJ Jubilee Makes History with Acoustic Bounce Show at Preservation Hall," Nola.com, November 9, 2013, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2013/11/dj_jubilee_makes_history_with.html. |

| 13. | Alison Fensterstock, "PressHall Brass Backed Fiend and Nesby Phips for a Wild Midnight Show at Preservation Hall," Nola.com, March 2, 2015, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2015/03/preshall_brass_backed_rappers.html. |

| 14. | See Scott Jordan, "The Rap on WWOZ," The Gambit, August 19, 2003, http://www.bestofneworleans.com/gambit/the-rap-on-wwoz/Content?oid=1241861. Rogan was an inspiration for Steve Zahn's DJ Davis McAlary character in David Simon's Tremé on HBO. While there are two commercial hip-hop/R&B radio stations in New Orleans at the time of writing—93.3FM and 102.9FM—both must abide by regulations set by the stations' corporate parents limiting local rap and bounce play, though both have made important advances in getting local rap on the air. See 93.3FM radio star Wild Wayne's oral history interview at http://www.nolahiphoparchive.com. |

| 15. | Ricky B, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, July 7, 2012, http://www.louisianadigitallibrary.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16313coll68/id/117/rec/39. |

| 16. | Alison Fensterstock, "Bounce Originator Ricky B Celebrates Album Release at Blue Nile April 5, along with the Stooges Brass Band," Nola.com, April 2, 2013, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2013/04/bounce_originator_ricky_b_cele.html. |

| 17. | Nesby Phips, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, July 13, 2014, http://www.louisianadigitallibrary.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16313coll68/id/117/rec/39. |

| 18. | See, among others, Insanul Ahmed, "Hate of the Union: When New York Disses The South,"Complex Magazine, July 1, 2010, http://www.complex.com/music/2010/07/hate-of-the-union-when-new-york-disses-the-south/; Darren E. Grem, "'The South Got Something to Say': Atlanta's Dirty South and the Southernization of Hip-hop America,"Southern Cultures 12, no. 4 (2006): 55–73; Ali Colleen Neff, Let the World Listen Right: The Mississippi Delta Hip-Hop Story (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2009); Roni Sarig, Third Coast: OutKast, Timbaland, and How Hip-Hop Became a Southern Thing (New York: Da Capo Press, 2007); and Ben Westhoff, Dirty South: OutKast, Lil Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern Rappers Who Reinvented Hip-hop (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011). |

| 19. | Travel writers and scholars have long characterized New Orleans as the most African of US cities, see Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, "The Formation of Afro-Creole Culture," in Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization, ed. Arnold R. Hirsch et al. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992), 58–87. Anthropologist Melville Herskovits argued that "those aspects of the African tradition peculiar to this specialized region have reached their greatest development [in New Orleans]" in The Myth of the Negro Past (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1941), 245. If, as Congolese scholar V. Y. Mudimbe has written, the representational function of Africa operates as a "sign of something else," then New Orleans, fetishized, exoticized, and romanticized ad nauseum, is a "sign of something else" writ large in the American psyche. See The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1988), ix. For an extended discussion of these dynamics, see Lewis Watts and Eric Porter, New Orleans Suite: Music and Culture in Transition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 5. As mass mediated images of Katrina "refugees" have informed much of the world's knowledge of black New Orleanians, these paradigms have become even more pronounced. See Zenia Kish, "Hiphop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora," American Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2009): 671–692. |

| 20. | Watts and Porter, New Orleans Suite, 7. See also Sakakeeny's discussion of New Orleans musicians and the tourism economy in Roll With It, 69–107. |

| 21. | See Nik Cohn, Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007); Daron Crawford and Pernell Russell, Beyond the Bricks, (New Orleans: Neighborhood Story Project, 2009); Miller, Bounce; and Sakakeeny, Roll With It, along with the work of journalists mentioned in note 8. |

| 22. | Capitalization derived from Truth Universal's preferred marketing of the event. |

| 23. | GRASSROOTS! was begun by Truth Universal in 2002 at the Neighborhood Gallery Theater on Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in the Central City neighborhood of New Orleans. At that time, the Neighborhood Gallery was a vital part of the city's black community-based business network. Begun by Sandra Berry and Joshua Walker in their living room on Soniat Street, the Neighborhood Gallery permanently closed after Hurricane Katrina. Truth relocated GRASSROOTS! to the Dragon's Den in 2007, where it remained until its final show in December of 2012. |

| 24. | Kish, "Hiphop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora," 672. |

| 25. | See Kish, "Hiphop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora," for a detailed account of post-Katrina rap and activism. |

| 26. | Representation is always a fraught proposition. Visit the NOLA Hip-hop Archive to hear artists speak about the complexity of representation in their own words. |

| 27. | The ethnographic moment presented here is an excerpt from my forthcoming dissertation, "'Shake Fo' Ya Hood': Hip-Hop and Recovery in Post-Katrina New Orleans." |

| 28. | "Hurricane Isaac Damaged 59,000 Homes in Louisiana, Officials Estimate," Associated Press, September 28, 2012, http://www.nola.com/hurricane/index.ssf/2012/09/hurricane_isaac_damaged_59000.html. |

| 29. | John Schwartz and Campbell Robertson, "New Orleans Levees Hold, and Outsiders Want In," New York Times, September 6, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/07/us/new-orleans-levees-hold-and-outsiders-want-in.html. |

| 30. | Bob Marshall, "Hurricane Isaac Lays Bare the Painful Economics of Flood Protection," The Lens, September 2, 2012, http://www.nola.com/hurricane/index.ssf/2012/09/hurricane_isaac_lays_bare_the.html. |

| 31. | KVLE, "Studio Life: How Dee-1's Parents Were Saved," 3 Little Digs, September 3, 2012, http://3littledigs.com/blog/2012/09/03/studio-life-dee-1/. |

| 32. | Dee-1, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, September 15, 2012, http://cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p16313coll68/id/4/rec/9. |

| 33. | The earliest act of sale for the building dates to 1882, although according to the Bourbon Group, the building was likely built twenty years before that date. |

| 34. | Mary Louise Christovich, Sally Kittredge Evans, and Roulhac Toledano, New Orleans Architecture: The Esplanade Ridge (New Orleans: Pelican Publishing, 1995), 18. |

| 35. | Alex Woodward, "Truth Universal Discusses His New Album and Politics in Hip-hop," The Gambit, September 10, 2013, http://www.bestofneworleans.com/gambit/universal-appeal/Content?oid=2250160. |

| 36. | I use quotes to denote widespread ambivalence about the use of the term. |

| 37. | "The Urbanist's New Orleans: What To Do," New York Magazine, April 1, 2012, http://nymag.com/travel/features/new-orleans-entertainment-2012-4/. |

| 38. | George Lipsitz, "Introduction: The Long Fetch of History; or, Why Music Matters," in Footsteps in the Dark: The Hidden Histories of Popular Music (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), vii–xxv. |

| 39. | Impulss, interview by Holly Hobbs, NOLA Hip Hop and Bounce Archive, June 4, 2012, http://cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p16313coll68/id/14/rec/22. |

| 40. | The writing of Alison Fensterstock, Matt Miller's work on Mia X, and Zenia Kish are notable exceptions to the erasure of women in New Orleans rap. |

| 41. | David Dennis, "Lyrikill—'Yes Inf**kingdeed' Video," The Smoking Section, August 30, 2011, http://uproxx.com/smokingsection/2011/08/lyrikill-yes-infkindeed-video/. |

| 42. | Tricia Rose, "A Style Nobody Can Deal With: Politics, Style and the Postindustrial City in Hip Hop," in Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture, ed. Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose (New York: Routledge, 1994), 72. |

| 43. | See Kelly M. Askew, Performing the Nation: Swahili Music and Cultural Politics in Tanzania (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 23. |

| 44. | Murray Forman, The 'Hood Comes First: Race, Space and Place in Rap and Hip-Hop (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2002), xvii. |

| 45. | Miller, Bounce, 1. |

| 46. | Marcyliena Morgan, The Real Hip-hop: Battling for Knowledge, Power and Respect in the LA Underground (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 5. |

| 47. | The event had been rescheduled from its usual August 29th date due to Hurricane Isaac. |

| 48. | Alison Fensterstock, "December 1 Edition of Truth Universal's 'Grassroots' Will Be Hip-hop Showcase's Last Monthly Event," Nola.com, November 30, 2012, http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2012/11/dec_1_edition_of_truth_univers.html. |