Overview

Stephanie Vander Wel reviews Jason Mellard's Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texan in Popular Culture (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2013).

Review

|

Jason Mellard's Progressive Country: How The 1970s Transformed The Texan in Popular Culture broadens our understanding of this musical style's dynamic role in negotiating the political contentions of a historical period marked by economic stagnation, political scandal, and the emerging cultural power of previously marginalized social groups. By linking the local music scene of Austin, Texas, to regional and national debates surrounding civil rights, the Chicano movement, and feminism, Mellard demonstrates how progressive country helped to shape and re-envision Anglo-Texan masculinity. The music's imagery, according to Mellard, embodies the complexities and contradictions of a liberal political ideology intertwined with the shifting symbolism of the rugged Texan. Through an eclectic blend of musical styles (rock, jazz, and country), Austin's music scene brought together seemingly opposing identities—the hippie (the emblem of youth counterculture) and the redneck (the standard representation of working-class Anglo-Texan masculinity)—in its formation of the cosmic cowboy. This "coming together of the hippies and the cowboys … signified an attempted coming-to-terms with the oppositions of urban and rural, modern and traditional, and the politico-cultural valences of left and right in the 1970s" (2). Mellard examines how progressive country dialogued with an ideology that combined nostalgia for an imperial Texas with progressive political ideals.

Referred to as "redneck rock" in Jan Reid's 1974 account of the Austin scene, "progressive country"—a term coined by local radio station KOKE-FM in 1972 to market a format for youth drawn to rock, pop, folk, and blues—combined countercultural psychedelic and pastoral sensibilities with country's bucolic portraits and urban styles (including western swing and honky-tonk).1Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (New York: Da Capo Press, 1974). Reid has revised this earlier book. See The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock: New Edition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004). Austin clubs, notably Armadillo World Headquarters (1970) and the Soap Creek Saloon (1973), encouraged a live performative aesthetic among a network of white, mostly male musicians (including Willie Nelson, Michael Murphy, Jerry Jeff Walker, Ray Wylie Hubbard, and Doug Sahm) with the exception being Marcia Ball, who were already living in Texas or had gravitated to Austin's heterogeneous soundscape from New York, Los Angeles, or Nashville.

|

| Armadillo World Headquarters, Austin, Texas, February 21, 2007. Photograph by Steve Hopson. Creative Commons License CC BY-SA 2.5. |

Chroniclers of progressive country have grappled with a scene that projected a dizzying array of cultural symbols and musical idioms on the national stage. Historian Barry Shank has detailed the development of Austin as a site of musical expression divorced from the explicit commercialization of popular music.2Barry Shank, Dissonant Identities: The Rock 'n' Roll Scene in Austin, Texas (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1994). Progressive country brought together white, working-class honky-tonk culture and Austin's folk communities (including liberal students at Austin's University of Texas campus) in a diversified blend one step removed from mass culture. Musicologist Travis Stimeling has delineated key sonic elements that helped shape the musical role of the cosmic cowboy in relation to fantasies of Anglo-Texan masculinity.3Travis Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin's Progressive Country Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). Stimeling also complicates the usual perceptions of progressive country's anti-commercial aesthetic by disclosing the shared musical practices and networks that connected Nashville's profit-oriented country music to Austin's community-oriented scene.

Mellard situates this music within the political fluidity of the 1970s, a contentious decade between the upheavals of the 1960s and the conservative reactions they provoked. Progressive country encapsulated the socio-political dynamics of Austin, the state of Texas, and the nation. "No Texan," writes Mellard about Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ), "could combine or transcend the contrarian qualities of traditional Texanness and modern liberalism" (163). Playing the part of the manly, uncouth Texan, LBJ signed crucial legislation of the civil rights era while stubbornly insisting that the United States remain in the increasingly violent and escalating Vietnam War. With Johnson's retirement from the White House and death in 1973, a vacuum emerged in the national and state Democratic Party and in the psyche of the Lone Star State. The rise of progressive country through figures such as Willie Nelson or the Greezy Wheels "served in part as an antidote to the 'vanishing' of LBJ" from the national stage. Enacting the redneck hippie, Nelson could "combine iconic Texasness and the airs of modern progressiveness" (163). What is significant about the "hippie-redneck" fusion, argues Mellard, is that it "exhibited these qualities in a moment heady for the denizens of Sunbelt Texas trying to find their post-1960s, post-civil rights, post-industrial footing" (99). The figure of the cosmic cowboy helped whites who identified with the romantic symbolism of Anglo-Texas's frontier past to navigate a shifting landscape that included the political and cultural voices of Chicanos, women, and blacks, challenging the imperial myths of the Lone Star State.

|  | |

| Howdy, Austin, Texas, October 2007. Photograph by Steve Hopson. Creative Commons License CC-BY-SA 2.5. | Texas Music, 2007. Photograph by Steve Hopson. Creative Commons License CC-BY-SA 2.5. |

Despite the book's title, progressive country is only one of the many expressive forms Mellard draws upon. In pursuit of other moments and materials sometimes the music gets pushed to the background. The first chapter ("The Empire of Texas: Lone Star Regionalism Sets the Stage, 1936–1968") explores the contradictions of the 1930s and 1940s writings of the Lone Star regionalists (folklorist Frank J. Dobie, historian Walter Prescott Webb, and naturalist Roy Bedicheck) associated with the University of Texas. This discourse glorified Texas's Anglo reputation for rugged individualism while advocating for New Deal policies, laying the foundation for the tenets of progressive liberalism later incorporated into the movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Later, Mellard examines 1970s nostalgia promulgated in the liberal Texas Observer and the Texas Monthly (published in Austin), providing an account of the anxieties surrounding the "Vanishing" Texan and the retrenchment of Texas masculinity. In "You a Real Cowboy?: Texas Chic in the Late Seventies," he reviews the iconic films The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (a 1978 Broadway play adapted for film in 1982) and Urban Cowboy (1980), as well as the television soap opera Dallas (1978–1991), connecting these representations of Texas popular culture to national phenomena (Ronald Reagan as cowboy or the Bush Family as oil barons) that accompanied and influenced the reddening of the United States and the westernizing of the Sunbelt.

|

| Vanishing Texas, Texas Monthly, November 1990. Cover. |

Mellard's interpretations of films and television shows provide nuance to the history of Texas iconography that sometimes goes missing in his close readings of music. When he brings up the role of satire in progressive country songs, his arguments can become strained. Like 1970s glam, progressive country, suggests Mellard, can provide a level of irony through emphasizing stereotypes of the free-loving hippie and the provincial redneck. But just how ironic depictions can transcend the dualism of the hippie-redneck alliance with rhetoric that highlights those very divisions, he doesn't make clear. Nor does Mellard carefully examine class and regional differences that place the white-middle class hippie against the white working-class redneck. The song that best realizes the deep-seated conflict between these two identities is Jerry Jeff Walker's 1973 performance of Ray Wylie Hubbard's "Up Against the Wall (Redneck Mother)"—about how a white, working-class honky-tonk patron spends his days "kickin' hippies' asses and raisin' hell." Mellard connects the song lyrically to Merle Haggard's "Okie from Muskogee," a portrait of rural, small-town values and pro-war sentiment that rails against the immoral flamboyance of the counterculture. In Mellard's analysis, "Up Against the Wall" "strains to close the cultural rift" opened by Haggard's 1969 "Okie" by making the satire in Hubbard's tune "more transparent and over-the-top, but still affectionate" (83). It's not hard to miss how the parodic performance of "Up Against the Wall" dramatizes the stereotypes of the violent and dangerous redneck against the socio-economic privileges of the interloping hippie. Rather than a form of satire affectionately poking fun, "Up Against the Wall" presents a commentary about the complexities and discord of the hippie's search for a peaceful reprieve in a working-class culture of disenfranchisement and the unruly redneck's fight against the hippie's middle-class subject position and left-leaning politics.

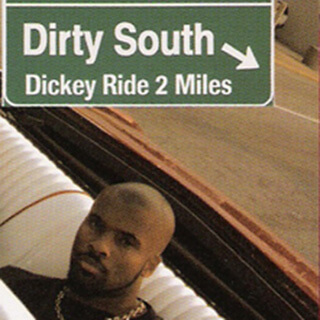

At times, Mellard overlooks the contradictory and intricate qualities of the actual music, most obviously when he contrasts the meaning of progressive country with that of the 1970s outlaw movement. While progressive country could encapsulate countercultural ideals, the outlaw movement jettisoned the hippie's embrace of social harmony to project a swaggering and rebellious masculinity that acted as a cultural backlash against the political gains of African Americans, women, and Chicanos at the state and national level. Mellard's account does not consider how the performance of machismo can conceal social fragility or uneasiness.4For a discussion of the relationship between representations of hypermasculinity and cultural disenfranchisement, see Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press), 103–104; and Robert Walser, "Forging Masculinity: Heavy Metal Sounds and Images of Gender" in Running With The Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press), 108–136. When outlaw country came to the forefront with 1976's Wanted! The Outlaws (featuring Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser), its enactments of masculine bravado could be understood as veils for masculine anxiety, especially in a postindustrial context in which white, working-class men were struggling to hold onto their "breadwinner" status.5Wanted! The Outlaws. RCA Victor, 1976.

|

| Wanted! The Outlaws, 1976. Album Cover. RCA Victor. © RCA Victor. |

Wanted! The Outlaws does not simply deploy songs of masculine rebellion, it also contains ballads of male vulnerability and heartache. Nelson's "You Left a Long, Long Time Ago" tells of the painful dissolution of a romantic union. Jennings's "Slow Movin' Outlaw" portrays the fragility of this displaced figure in a fast-changing world. Stimeling has argued that even in songs steeped in the imagery of masculine bravado (such as 1973's "Lonesome, On'ry, and Mean"), the sonic nuances of Jennings's vocal performance and production "reveals this stance to be a façade that masks profound insecurity."6Travis Stimeling, "Narrative, Vocal Staging, and Masculinity in the 'Outlaw' Country Music of Waylon Jennings," Popular Music 32, no. 3 (October 2013): 343–358.

Mellard could have strengthened his arguments about the significance of the outlaw movement if he had connected the actual music to his "Vanishing Texas" thesis regarding the 1970s nostalgia for a lost masculine self. With the political emergence of previously marginalized racial, ethnic, and gendered voices, the "Vanishing Texan," writes Mellard, "augured not the disappearance of Texanness, but also an anxiety over the new contours of that identity in the absence of Anglo-masculine normativity" (130). Outlaw country nostalgically clung to standard representations of masculinity while articulating a level of uneasiness and vulnerability arising from the shifting socio-political topography of the 1970s.

Progressive Country is an important book exploring Texas identity. From LBJ to W, the performative dimensions of Anglo-Texan masculinity helped shape an imagined national identity that could "navigate its rising geopolitical profile" (23). Within this narrative, Mellard underscores the ways progressive country provided the imagery of the "cosmic cowboy" to bridge past and present in the face of the political transfigurations of the 1970s.

About the Author

Stephanie Vander Wel is assistant professor of historical musicology at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. Her work has appeared in Musical Quarterly, and she is a contributing author to The Grove Dictionary of American Music, Second Edition. She is currently finishing The Singing Voices of Hillbilly Maidens and Cowboys’ Sweethearts: Country Music and the Gendering of Class, 1930s–1950s (University of Illinois Press).

Recommended Resources

Text

Reid, Jan. The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock: New Edition. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Shank, Barry. Dissonant Identities: The Rock 'n' Roll Scene in Austin, Texas. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1994.

Stimeling, Travis. Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin's Progressive Country Music Scene. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Audio/Video

Michael Murphy's Cosmic Cowboys Souvenir. A&M, 1973. LP Vinyl.

Viva! Terlingua! Nuevo!: Sons of Luckenback, Texas. MCA, 1973. LP Vinyl.

Wanted! The Outlaws. RCA Victor, 1976. LP Vinyl.

Willie Nelson's 4th of July Picnic. Directed by Yabo Yablonski. La Paz Productions, 1974. Video cassette.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (New York: Da Capo Press, 1974). Reid has revised this earlier book. See The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock: New Edition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Barry Shank, Dissonant Identities: The Rock 'n' Roll Scene in Austin, Texas (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1994). |

| 3. | Travis Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin's Progressive Country Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). |

| 4. | For a discussion of the relationship between representations of hypermasculinity and cultural disenfranchisement, see Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press), 103–104; and Robert Walser, "Forging Masculinity: Heavy Metal Sounds and Images of Gender" in Running With The Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press), 108–136. |

| 5. | Wanted! The Outlaws. RCA Victor, 1976. |

| 6. | Travis Stimeling, "Narrative, Vocal Staging, and Masculinity in the 'Outlaw' Country Music of Waylon Jennings," Popular Music 32, no. 3 (October 2013): 343–358. |