Overview

Mark Nunes considers Roger May's Looking at Appalachia, a crowdsourced photography archive of spaces, places, and people in Appalachia, drawn from the work of many photographers of the region. As this online project reproduces and challenges tropes of Appalachian photography, Nunes describes how it encourages openness to documenting and delimiting the boundaries of Appalachian representation.

Digital Spaces is an ongoing collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia projects that deploy digital scholarship in the study of real and imagined geographies.

Introduction

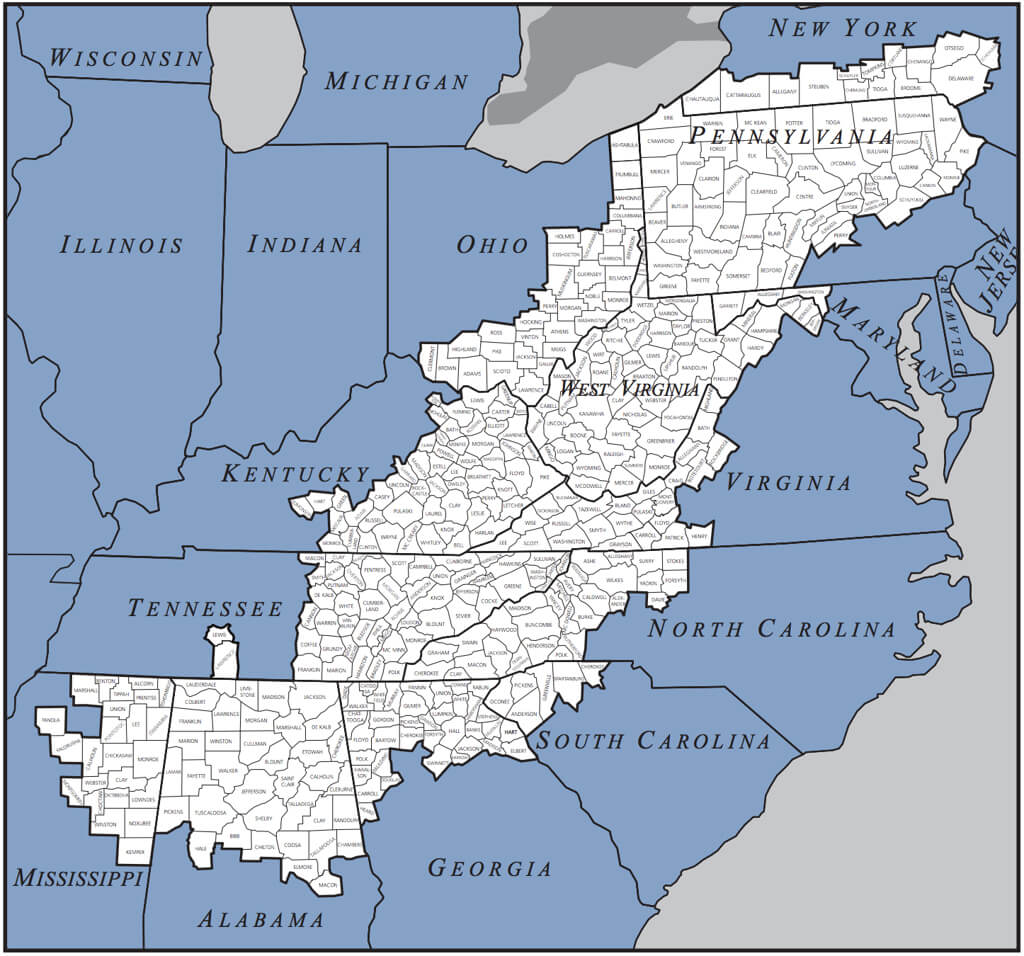

Of countless images over the last century, attempts to frame Appalachia's landscape and people have drawn on a limited number of tropes. Whether Bayard Wootten's photographic illustrations for Cabins in the Laurel,1Muriel Earley Sheppard, Cabins in the Laurel (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1935, 1991 reprint). or the Farm Security Administration (FSA) images of Walker Evans, Elmer Johnson, and Marion Post Wolcott, or photojournalists' frontline depictions of the War on Poverty, the visual encoding of Appalachia has reinforced and recirculated images of a rugged, yet pristine landscape, and a people who are portrayed in equal mixtures of pride and deprivation, perseverance and lack. Without question Appalachia "as a whole" presents a rather problematic construct, embracing a diverse cultural and physical geography with multiple, conflicting borders and covering—by the Appalachian Regional Commission's (ARC) definition—420 counties in thirteen states. The volume of images depicting Appalachia belies diversity, reinforcing instead a homogenized depiction of the "region." That such a broad space and numerous people—congressionally constructed—becomes reduced to one region is itself an oversimplification. A Google image search of "Appalachian photography" reveals visual stereotypes in present-day action, and their limited scope.

While these stereotypical depictions of the region exist across a broad range of media, photography has a way of literalizing this act of framing certain images at the expense of others. But alongside the many attempts to traffic in Appalachian images for commercial or political gain, projects exist that question how photography frames Appalachia: what is contained and what excluded. This effort dates back to some of those images of the FSA Photographic Unit. As Marion Post Wolcott noted, "Constantly we were asked [by Unit Director Roy Stryker] and [we were] asking of ourselves, 'In what direction are we going; are we doing the whole job? How can we fill in the gaps, round out the file…?'"2Betty Rivard, ed. New Deal Photographs of West Virginia, 1934–1943 (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2012), 143. In a similar spirit, Roger May's crowdsourced photography project, Looking at Appalachia (begun in 2014, and ongoing) seeks a broader picture. This collection of images engages in a multivalent and ambivalent approach to framing Appalachia, presenting over four hundred photographs taken by more than one hundred photographers across multiple counties in thirteen states. To visit this collection is to experience "unseeing" the region through multiple frames and lenses. This strategy of "visual counter point," as May describes it, attempts to create a complex and contradictory "crowdsourced image archive [that] will serve as a reference that is defined by its people as opposed to political legislation."3Roger May, "Overview," Looking at Appalachia, 2014, http://lookingatappalachia.org/overview.

Most striking in this "visual counter point" is the degree to which the project is fundamentally frustrating. Each time an image seems to frame Appalachia in a particular way, other images unsettle the frame. As Susan Sontag suggests in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), "the photographic image… cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened. It is always the image that someone chose; to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude."4Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), 46. Unlike Wolcott and Stryker's challenge of "doing the whole job," Looking at Appalachia's use of multiple, competing frames undermines any attempt to portray a region in its entirety, or to pin this floating signifier within a fixed, defined border. But, at the same time, each of these images invites us to look at Appalachia—to see Appalachia and what it signifies in this particular image. These multiple, at times contradictory perspectives yield an increasingly complex sense of speakers and voices; as Looking at Appalachia contributor Lou Murrey explains in her commentary on May's project and several other online, collaborative photography projects: "All around Appalachia there are photographers engaged in a dialogue to change and expand perception of the region, allowing folks to declare 'hey, I'm Appalachian too.'"5Lou Murrey, "Out of Frame: Regional Stereotypes in Photography." Appalachian Voices, December 19, 2015. http://appvoices.org/2015/12/19/regional-stereotypes-in-photography/. What is particularly compelling about Looking at Appalachia is that the dialogic qualities of this crowdsourced work find expression in both form and content. Individual pictures declare "I'm Appalachian too," by calling attention to the frames that select these images. As William Schumann has noted in "Place and Place-Making in Appalachia," region is a social and historical construct, emerging through "a process of selectively cultivating some narratives of belonging while erasing other meanings from public discourse."6William Schumann, "Introduction: Place and Place-Making in Appalachia." In Appalachia Revisited: New Perspectives on Place, Tradition, and Progress, ed. William Schumann and Rebecca Adkins Fletcher (Bowling Green: University of Kentucky Press, 2016), 9. The project is fundamentally unsettling to the extent that powerful and idiosyncratic framings do not coalesce into any easy sense of what "Appalachia" signifies, but call attention to acts of inclusion and exclusion. By design, viewers are left in productive confusion, wondering what "region" means in this mixing of frames and images. The project intentionally draws upon the highly problematic ARC-defined boundary for Appalachia for its submission criterion at the same time that it challenges how these borders have framed a regional imaginary. "Appalachia's boundaries," David Whisnant writes, "have been drawn so many times by so many different hands that it is futile to look for a 'correct' definition of the region."7David E. Whisnant, Modernizing the Mountaineer: People, Power and Planning in Appalachia (Boone, NC: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1980), 134. Looking at Appalachia does not offer a "correct" narrative of belonging. It strives to provide a crowdsourced corrective to the dominant visual tropes for Appalachia through its use of multiple, competing frames.

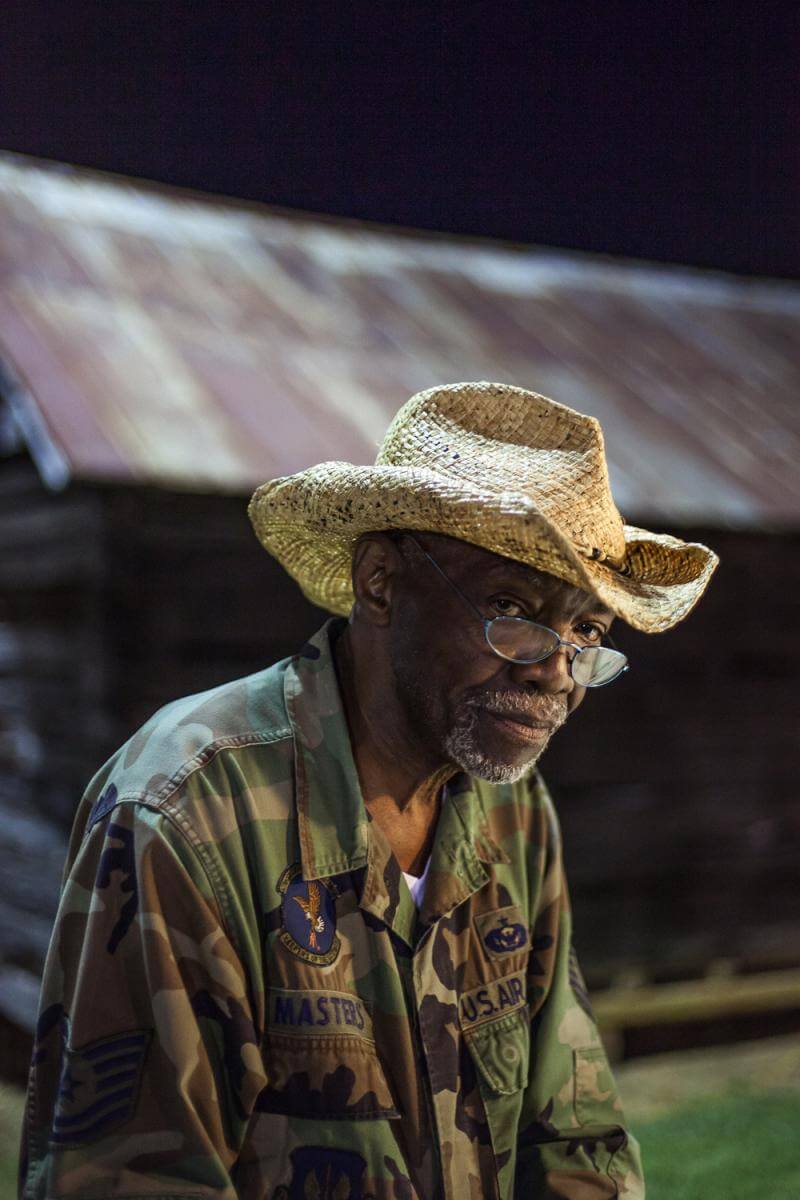

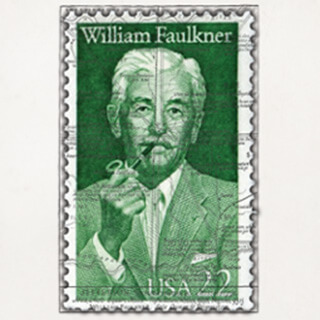

The diversity of images in Looking at Appalachia also reveals the degree to which photographic meaning-making depends upon the power of visual citation. The crowdsourced call to photographers produces clusters of family resemblances in a manner not unlike the same-yet-different clustering that emerges through the social media practice of tagging photographs (for example, the #appalachia hashtag on Instagram.) As Sontag notes, "photographs echo other photographs"8Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 84.; we recognize something in Tamara Reynolds's portrait of a Tennessee man's face (Figure 1), a semiotic resemblance that, when framed as "a face of Appalachia" contributes to the "substantiating archives of images, representative images, which encapsulate common ideas of significance and trigger predictable thoughts, feelings." In these moments of recognition, ideologies take visual form that "commemorate—in no less blunt fashion than postage stamps"—embedded values.9Ibid., 84–86. But as the number of photographers creating these images increases, commemoration becomes an increasingly granular—and increasingly ordinary—act. As Fred Ritchin writes in his discussion of the impact of social media on contemporary photojournalism, the proliferation of images documenting any single event tends to create not only greater variation in the images recorded, but also a greater number of photographs that are "more detail-oriented and everyday, with fewer elaborately constructed attempts at the larger, synthesizing statement."10Fred Ritchin, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen (New York: Aperture, 2013), 11. While an editorial board curates content included in Looking at Appalachia, the project taps into the diffusive power of crowdsourcing with the same intent: to use multiple, idiosyncratic perspectives from professional and amateur photographers alike to refract Appalachia, resisting reduction of these multifaceted photographs into a blunt commemoration.

Visual Dialogues: A Mosaic of Appalachia

In After Photography (2009), Ritchin suggests that the digital photograph acts less as "window" than "mosaic," not only because any digital image consists of pixels, but because once digital, any image exists as a link within a larger network.11Fred Ritchin, After Photography (New York: Norton, 2009), 70. Photography in a networked environment "is far from a mechanical recording; it becomes a collaborative, multivocal interrogation of both external and internal realities in which the initial exposure is only a minimalist starting point."12Ibid., 75. In Looking at Appalachia each photograph speaks to "Appalachia" in its own way, while commenting upon the reality that other images purport. Looking at Appalachia offers a mosaic of disparate images in dialogue with one another. Any image added to the mosaic does not move us closer to completion but only complicates attempts to define a "region." Because the network is always an open-ended structure, an open call for additional contexts, commentaries, and contributions, the project can never be "finished"—even after the editorial board stops adding images. It is in those gaps and contradictions among a large array that the project succeeds in evoking a sense of Appalachia while offering less and less certainty as to what exactly Appalachia contains.

Looking at Appalachia also challenges the power to exclude through the framing of visual design, juxtaposing photographs in a grid layout reminiscent of other photosharing social media services, such as Instagram, Trover, or Flickr. To return to Tamara Reynolds's portrait: this image does not present itself in isolation when we first encounter it. It is already in dialogue with other images—some sharing the same echoes of recognition (perhaps Jaclyn Brown's portrait of Bill Mullaly from Knoxville), while others (an image from the Corazon Latino Festival in Jonesborough) calling attention to all that falls outside the frame of this photograph (Figure 2). Appearing directly above in the image grid is a photograph of a young, blonde-haired woman in sunglasses, head hanging out of a demolition derby car at the Crossville Raceway in Cumberland County. While this image may echo well with other visual tropes for (Southern) Appalachia by way of NASCAR and its mythologized connection to moonshine running, it is not an image that speaks in the same semiotic registers as Reynolds's portrait. Yet both photographs—taken at the same location by the same photographer—contribute to the Appalachian imaginary. Juxtaposed and conflicting images of the same scene call attention to what Judith Butler has termed "frames of recognition"—normative structures that allow recognition of a subject as such, but only through an attempt to exclude or cast off aspects of the subject that "exceed the normative conditions of its recognizability."13Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009), 4. As with the playful series of photographs that went viral in 2015, in which images of a beautifully crafted meal, a woman seated on an empty beach, and a solitary bicycle on an empty road appear in their Instagram frame and in a broader frame that captured everything just outside of that "perfect shot," viewing iconic face and demolition derby car side by side in a grid of competing images reveals how framing is anything but a neutral act, and how any frame depends as much on visual citations of norms that give rise to recognition as it does excluding everything "already outside, which made the very sense of the inside possible, recognizable."14Ibid., 9.

If the imperative of the frame insists, "Look at this (and not that)," then the design strategy of juxtaposing images by diverse photographers with divergent visions compels recognition of what is just beyond the frame—to "look at this and that." The website's overall hypertextual design reinforces this visual tension between framing and what falls outside. Looking at Appalachia greets visitors with a cover image, a logo, links to information about the project, and a menu that invites users to choose a state within the thirteen-state ARC-designated region. The site directs users to select—to frame by state—one set of images of Appalachia over other sets. How viewers engage with the site determines their initial frame of context—whether proceeding alphabetically (Alabama), or via a state considered more central to their understanding (West Virginia) or perhaps beginning with a state that they might only marginally connect with Appalachia (Mississippi). While the site has many points of entry, it offers no final resting point, only a growing number of juxtaposing images, and an increasingly complex mosaic of Appalachia.

Certain images in Looking at Appalachia affirm and commemorate popular cultural assumptions. Consider the contribution of Shelby Lee Adams, a photographer of Central Appalachia who, since the mid-1970s, has garnered considerable attention—and criticism—for creating portraits that would seem to perpetuate stereotypical images of rural deprivation and depravity—what Jason Huettner has called "poverty porn."15Jason Huettner, "Capitalist Realism or Poverty Porn?" Hyperallergic, July 7, 2011, https://hyperallergic.com/28555/capitalist-realism-or-poverty-porn. See also Larry Vonalt, "The Dignity of Shelby Lee Adams's 'Disturbing' Family Photography." Studies in Popular Culture 29.2 (October 2006): 110–121. Adams has only one work included in the project, which, for those only familiar with his more controversial images, may seem a departure of sorts, though one still resonant with Appalachian stereotypes: A portrait of one-hundred-year-old Barbara, from Perry County, Kentucky. The image affirms deeply inscribed indices of the Appalachian "granny" stereotype: her aged face, whiteness, and rugged cheer. But in the mosaic presentation of images on the Kentucky page, her portrait abuts Trey Jolly's landscape of the Daniel Boone Plaza, also in Perry County—a mountaintop removal reclamation site (Figures 3, 4, 5). The nostalgia framing recognition for one photograph only maintains itself as a stereotypical image of Appalachia through exclusion of other images that lie outside the frame—images of extraction and reclamation that are just as much a normative frame as Barbara's weathered and aged face. At the same time, Adams's portrait of this mountain woman asserts itself with equal weight as a counterpoint to the stereotypical framing of Appalachia as a sacrifice zone. Photographs echo one another in ways that both cancel and amplify resonant spatial representations. No single frame can contain Appalachia and its competing significations.

There is reason to closely consider this stereotypical photograph by Adams. In a June 2016 email exchange, May describes Adams as "the first living photographer I entered into conversation with" regarding what it meant to "look at" Appalachia through the lens of a camera and frame it in a particular way. In an essay published on May's blog, Walk Your Camera, Adams situates his work as a visual response to the War on Poverty imagery of the 1960s, which he describes as an ongoing "embarrassment to all."16Shelby Lee Adams, "The Work of Looking." Walk Your Camera, September 7, 2012, http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-shelby-lee-adams-part-one/. Like Adams, May casts Looking at Appalachia—launched to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the War on Poverty—as an attempt to unravel the "visual definition of Appalachia" that codified over the ensuing half century through the heavy circulation and citation of those images in the mass media.17May, "Overview." While Adams's photographs, like the portrait of Barbara included in Looking at Appalachia, may seem to operate within the same echo chamber of iconic images and visual tropes captured in these Great Society-era photographs, Adams explains that the visual stereotypes that structure Appalachia in the popular imagination are likewise part of his own emplacement in this space. They operate as normative frames that give rise to recognizability. Acknowledging this provides an opportunity to engage in what Adams describes as "the work of looking" in photography:

Our ancestral mountain people are mythologized into our greater existence from our beginnings, a part of our childhood and permanent memories. If we are truly honest with ourselves, we know this cannot be erased. If you are from these mountains, your and my dreams and reality itself are engraved within this collective group consciousness forever. One can choose to repress, but sooner or later, the lives and images of our mountain people will return to us and keep returning until we come to terms with their importance, not just the ones we chose, but all. 18Adams, "The Work of Looking."

He goes on to describe photographs as "catalysts" that can complicate these stereotypes through this work of looking.19Ibid. May admits that his initial response to Adams's photographs was to "dismiss the work as typical stereotyping of Appalachia," yet in confronting those photographs, he likewise had to come to terms with his own embedded stereotypes.20Roger May, "Looking at Appalachia: Shelby Lee Adams—Part Two," Walk Your Camera, September 15, 2012. http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-shelby-lee-adams-part-two/. By including Adams's portrait of Barbara alongside other photographs that echo competing, iconic images of Appalachia, the project offers its audience an opportunity to catch themselves in the act of recognition, and to question what it is they are recognizing. This play of frames serves as a central feature of how Looking at Appalachia operates, in concept and design—"fram[ing] the frame" that attempts to delimit Appalachia in each of these juxtaposed images. 21Butler, Frames, 9.

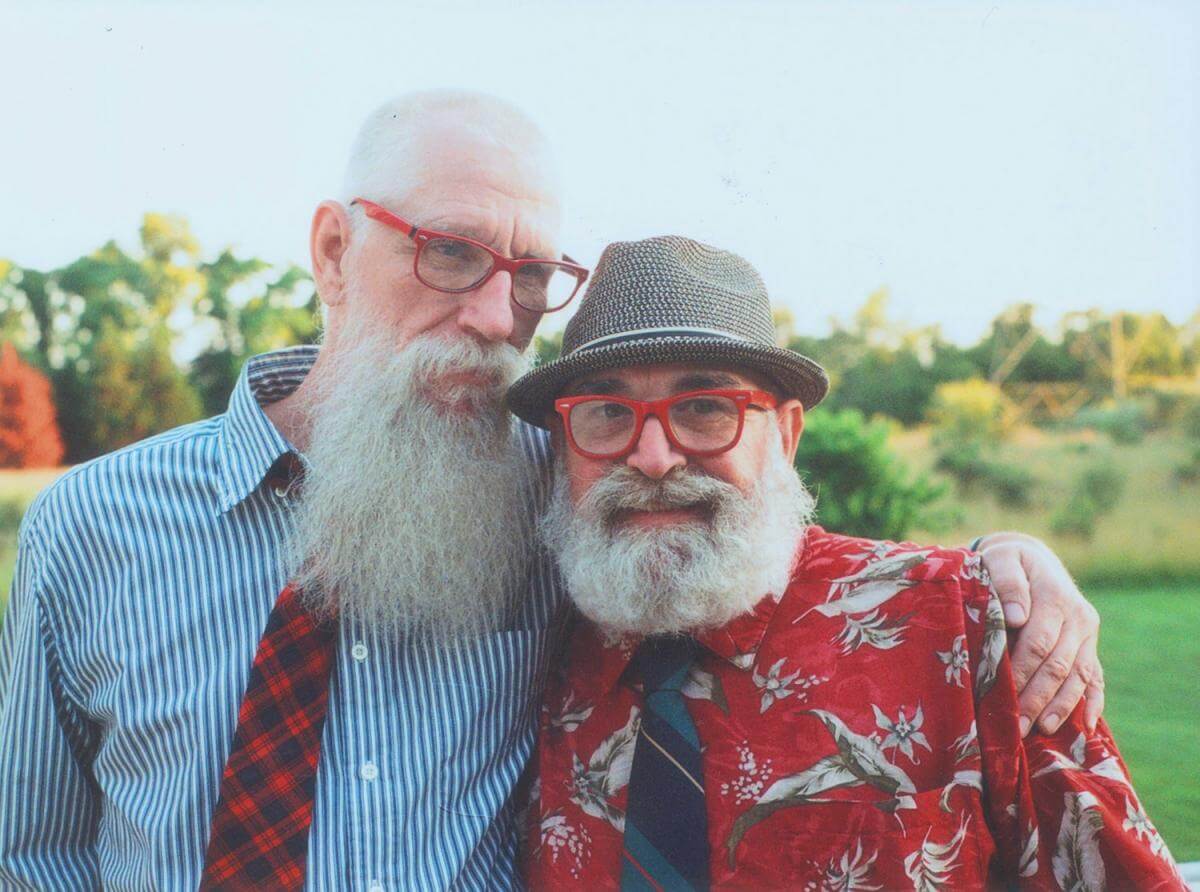

It should come as no surprise that Looking at Appalachia traffics in some of the frames of recognition that the project might be expected to attempt to undo. But this crowdsourced collection of images functions collaboratively within a mosaic that shows the recognizable as well as the frame that allows its recognition. Consider the cluster of images depicting bearded men, and the frame of reference within which these images operate. The mountaineer beard is an iconic image of Appalachian masculinity, repeated in university mascot as well as hillbilly stereotype. As beards echo other beards, a visual exchange develops, offering a complex portrait of Appalachian masculinity. A series of three images by photographer Elle Olivia Andersen of Robert Pickens, from Pickens County, South Carolina, offers a frame for the mountaineer that seems to confirm the stereotype—gray-bearded, capped, and wearing overalls (Figures 6, 7, 8). The photographs assert a documentary authority, capturing an "authentic portrait" of Appalachian life. But these images—and this beard—stand in dialogue with other images of bearded men that work against the authority of any one frame. As counterpoint, consider the portrait from Madison, Kentucky, of a younger mountaineer, bearded, but in a hat one would never confuse with an iconic "toboggan" (Figure 9). Other beards appear in other semiotic constellations that suggest an Appalachia outside the frame of any singular attempt to define the "mountain man" (Figures 10, 11, 12). The same visual conversation occurs when the gendered "granny" stereotype in Adams's portrait of Barbara is repeated and contradicted in other photographers' images of Appalachian women, old and young. With each echo of recognition, viewers see "mountain women" and "beards of Appalachia," but as these framed portraits engage one another, they ask, rather than answer: What makes these images recognizable? When you look at Appalachia, what is it that you see?

Frames of Recognition

Butler suggests how frames operate as normative structures giving rise to recognizability and representability: "When a picture is framed, any number of ways of commenting on or extending the picture may be at stake. But the frame tends to function, even in a minimalist form, as an editorial embellishment of the image, if not a self-commentary on the history of the frame itself."22Ibid., 8. Framing is an interpretive act, embedded in the photograph, a material instantiation of various norms of recognizability. "Even the most transparent of documentary images is framed, and framed for a purpose," she writes, "carrying that purpose within its frame and implementing it through the frame."23Ibid., 70. Recognizability is "both jettisoning and presenting" the norms of representation and interpretation, "doing both at once."24Ibid., 73. The "iterable structure" of the frame—the fact that "the frame breaks with itself to reproduce itself"—gives rise to an inherent instability in this interpretive moment.25Ibid., 24. In one sense, Butler notes, "to be framed" implies that one has been set up—the subject of a "false accusation"; but because the frame is always vulnerable to exposing itself, to showing how this interpretive "break" in context operates (jettisoning and presenting), it also marks a potential for "breaking out" of normative structures of recognizability.26Ibid., 11 She writes of these moments of destabilization: "What happens when a frame breaks with itself is that a taken-for-granted reality is called into question, exposing the orchestrating designs of the authority who sought to control the frame. This suggests that it is not only a question of finding new content, but also of working with received renditions of reality to show how they can and do break with themselves."27Ibid., 12.

In a similar move, Looking at Appalachia breaks with itself by offering and destabilizing recognizable norms of Appalachian photography. Returning to the portraits of Robert Pickens (Figures 6, 7, 8), the frame seems to affirm the "quaint but stalwart mountaineer."28John Alexander Williams, Appalachia: A History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 199. The project as a whole, however, provides multiple iterations of this normative structure that break with themselves through multiple, contradictory framings. Even before Horace Kephart's popular depiction of "mountain whites" in Our Southern Highlanders (1922), the recognizable mountaineer identity has featured a normative whiteness exclusive of the racial and ethnic diversity significant in Appalachian demography.29Williams, Appalachia, 210–211; Horace Kephart, Our Southern Highlanders: A Narrative of Adventure in the Southern Appalachians and a Study of Life Among the Mountaineers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1922, 1984 reprint). See also: Patricia D. Beaver and Helen M. Lewis, "Uncovering the Trail of Ethnic Denial: Ethnicity in Appalachia." In Cultural Diversity in the U.S. South: Anthropological Contributions to a Region in Transition, ed. Carol E. Hill and Patricia D. Beaver (Athens: University of Georgia Press), 51–68; Schumann, "Introduction."

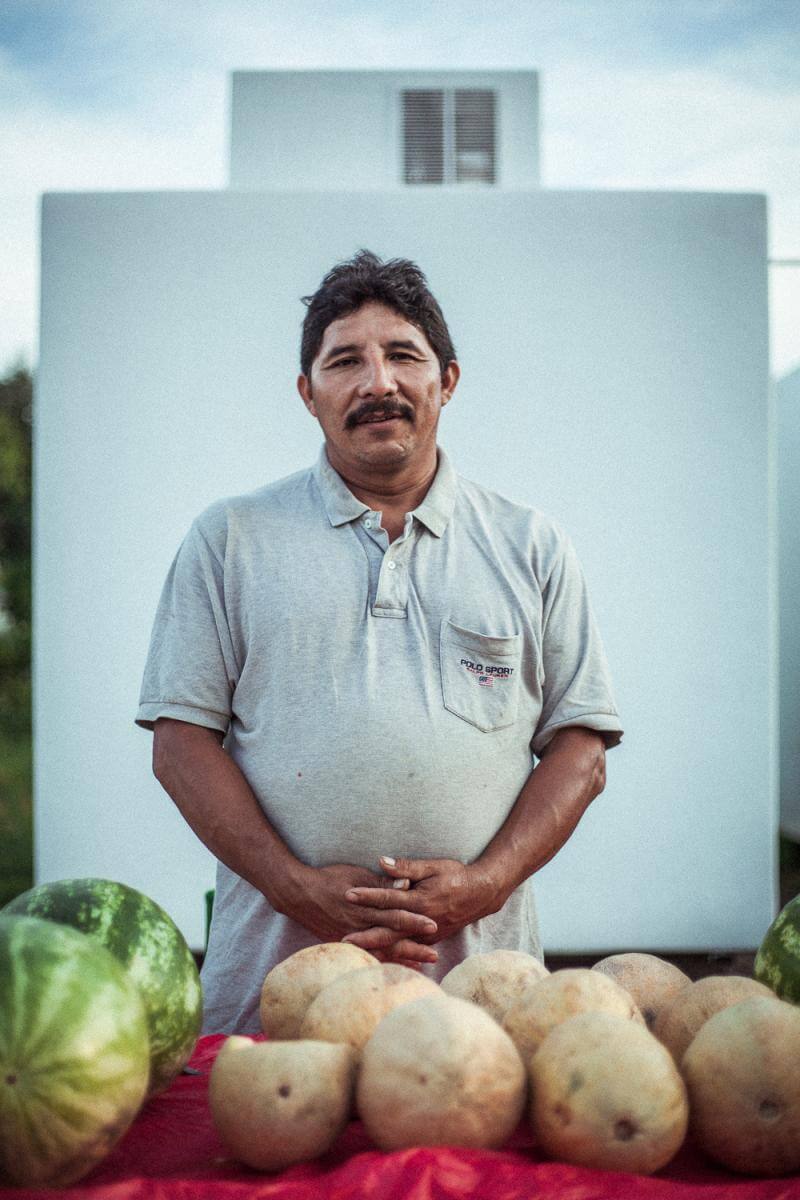

Figures 13–16

Numerous portraits within this collection of photographs speak directly to this erasure, and do so by asking viewers to question the recognizability of an Appalachia that reveals its racial and ethnic diversity. To see echoes of the same norms of representation that give us the "stalwart mountaineer," presented in portraits of African American Appalachian men, offers the normative frame of recognition and a break with its own terms for recognizability (Figures 13, 14). Similarly, while immigrant labor populations have moved into and out of the mountains throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and found their way, for example, into FSA documentation of Appalachian coal towns, ethnic diversity frequently falls outside of the frame of recognizability for "mountain folk."30Rivard, New Deal, 2012. Looking at Appalachia returns these often-erased and overlooked images to a visual dialogue, and does so within recognizable frames that reveal "received renditions of reality" at the same time that they destabilize the authoritative claim of these normative structures. Contemporary photographs of Hispanic mountaineers affirm and destabilize norms of representation (Figures 15, 16). "To learn to see the frame that blinds us to what we see is no easy matter," writes Butler.31Butler, Frames, 100.

Looking at Appalachia's contemporary, crowdsourced images destabilize normative frames of Appalachian nostalgia through photographs of a more mainstream place that works its way in and through recognizable visible tropes of quaint and simple country life. As Williams and others have noted, from the local color writers movement of the late 1800s onward, Appalachia appears as a "reservoir of American folk culture."32Williams, Appalachia, 204. Images outside of this framing reveal acts of selective focus. As Watkins notes of Wootten's 1930s photographs of Spruce Pine and Bakersville, North Carolina, her choice of camera angles and framing emphasized quaintness over development: "Had the camera been placed further back up the street," he notes, in his reading of one image, "the picture would have shown, among other things, a newer department store and a movie theater, more recognizable signs of modernity."33Charles Alan Watkins, "Merchandising the Mountaineer: Photography, the Great Depression, and 'Cabins in the Laurel.'" Appalachian Journal 12.3 (Spring 1985): 227. Williams makes a similar observation: images that "placed [Appalachia] squarely in the American mainstream" historically have been marginalized to make room for more recognizable, nostalgic framings.34Williams, Appalachia, 300. As with depictions of grannies, beards, and mountaineers, Looking at Appalachia does present images that seem throwbacks. Consider Meg Wilson's portrait from Garrard County, Kentucky, of two generations (is it grandfather and grandson?) in a tobacco barn (Figure 17). There are echoes of nostalgia. But the Angry Birds image on the boy's T-shirt connects this scene to traditional Kentucky tobacco farming practices as well as global networks of mobile devices, digital games, and franchise marketing. Similarly, Lou Murrey's candid shot at Skate World in Vilas, North Carolina, frames Appalachia in ways that foreground nostalgia for an imagined simpler and remote American past (Figure 18). A closer look reveals the smartphone in the woman's hand behind the counter, locating this image squarely within the broader context of highly networked American mainstream culture. These moments of contradiction—within and between photographs—create a tension within the project that undermines the authority of these normative frames.

Figures 19–23

Similarly, nature photography in Looking at Appalachia complicates and questions received and expected visual tropes. Chris Jackson's portrait of a young couple walking at the edge of Virginia's Falling Springs waterfall, or Nathan Armes's image of a dirt road on Wayah Bald in North Carolina, echoes photographs framing Appalachian geography as wild refuge (Figures 19, 20). Images of Appalachia as a sacrifice zone reinforce these norms by presenting the opposite—such as Dobree Adams's active mining sites in Perry County, Kentucky, or Pat Jarret's photograph of the Freedom Industries' chemical spill site in Charleston, West Virginia (Figures 21, 22). Other "natural settings" alter these frames: does Amanda Greene's North Georgia Christmas tree farm landscape, with portable toilet in the foreground, offer an image of untouched nature, extractive economy, or something in between (Figure 23)? Or consider Wes Frazer's photograph of a youth in mid-swing over a river in Jefferson County, Alabama (Figure 24). Not only does this image echo other representations of the region as a locus of simple country pleasures (destabilized, of course, by other images in Looking at Appalachia—for example, another Frazer photograph of a tattooed youth huffing inhalants while standing in the same river) but it also depicts Appalachia as a wild and rural refuge from urban and suburban development. But this first Frazer photograph disrupts its own image of Appalachia as simple, rural refuge by including the large pile of trash on the shore. Cropping out the trash would present a very different image. It is not ironic contrast (no more so than an Angry Birds T-shirt within a tobacco barn); rather, it is an acknowledgement of both the complexity of the region and the norms that come into play when we frame Appalachia through these powerful structures of recognizability.

The logic and design of Looking at Appalachia includes as many images as possible in a collaborative mosaic. In a June 2016 email correspondence, May dates the origin of Looking at Appalachia to his reflection on the work of William Gedney, a War on Poverty-era photographer who managed to see more than most photojournalists. May wondered how Gedney "somehow…made photographs of grace, beauty, and simple existence all the while capturing the hardscrabble environs of his subjects."35Roger May, "Looking at Appalachia: William Gedney—Part One." Walk Your Camera, July 1, 2012. http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-william-gedney-part-one/. May finds in Gedney's work "moments so obviously absent from most of the work…from Appalachia, that one has to wonder why so few photographs like this exist."36Roger May, "Looking at Appalachia: William Gedney—Part Two," Walk Your Camera, August 4, 2012. http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-william-gedney-part-two/.

That Appalachia has operated far more as a narrative construct than a geographic location—as Williams phrases it, "a place that always will be—and never was"—makes Looking at Appalachia a powerful interrogation of how frames of recognition operate, and how photography can simultaneously affirm and destabilize these powerful visual tropes.37Williams, Appalachia. Looking at Appalachia succeeds in part because crowdsourcing has become a common practice. And perhaps, as Ritchin (2013) suggests, the superabundance of images and image recording devices has moved us into a "postphotographic" era in which "the image output from a camera is no longer thought of as being, or needing to be, above all a recording:

The photographer need not explain clearly, but can share his or her impressions with other viewers who might be able to help to figure it out. Images containing ideas not yet sufficiently explicated, based on the photographer's knowing or sensing that something of importance is happening, can be construed as invitations to a reader to join in the search for meanings. Thus the image becomes, in a sense, open source.38Ritchin, Bending the Frame, 49.

Looking at Appalachia encourages an open relationship to documenting and delimiting the boundaries of representation, suggesting that while we recognize Appalachia in these images, we recognize the possibility of other ways of seeing it.39Ibid., 50. Each photograph speaks to Appalachia in some way, but what it speaks to is often just outside the frame.

About the Author

Mark Nunes is the chair of the Department of Cultural, Gender, and Global Studies at Appalachian State University. He is author of Cyberspaces of Everyday Life (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), which explores how the Internet restructures our everyday experience of the public and the private, and the local and the global. He is also editor of and contributing author for a collection of essays entitled Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures (New York: Continuum, 2011), which examines how the concepts of "noise" and "error" structure modes of cultural resistance in a network society.

Recommended Resources

Text

Billings, Dwight, Gurney Norman and Katherine Ledford, eds. Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? New York: Verso, 2009.

Caudill, Harry M. Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Era. Ashland, KY: Jesse Stuart Foundation, 2001.

Modrak, Rebekah and Bill Anthes. Reframing Photography: Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Rice, Connie Park and Marie Tedesco, eds. Women of the Mountain South: Identity, Work, and Activism. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015.

Schumann, William and Rebecca Adkins Fletcher, eds. Appalachia Revisited: New Perspectives on Place, Tradition, and Progress. Bowling Green: University of Kentucky Press, 2016.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador, 2003.

Underwood, David, ed. Rich Community: An Anthology of Appalachian Photographers. Knoxville, TN: Sapling Grove Press, 2015.

Williams, John Alexander. Appalachia: A History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Web

Appalachian Oral History Project Interviews, 1965–1989. Appalachian State University. 2008. http://omeka.library.appstate.edu/collections/show/7.

The Collaborative for Southern Appalachian Studies. 2017. http://collaborative.sewanee.edu.

Digital Heritage: Connecting Appalachian Culture and Traditions with the World. Western Carolina University. Accessed October 2, 2017. https://digitalheritage.org.

Digital Library of Appalachia. Accessed October 2, 2017. http://dla.acaweb.org/cdm.

Gonzalez, David. "Looking at Appalachia Anew." New York Times, May 20, 2015. https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/05/20/looking-at-appalachia-anew.

May, Roger. Looking at Appalachia. 2017. http://lookingatappalachia.org.

Murrey, Lou. "Out of Frame: Regional Stereotypes in Photography." Appalachian Voices, December 19, 2015. http://appvoices.org/2015/12/19/regional-stereotypes-in-photography.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Muriel Earley Sheppard, Cabins in the Laurel (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1935, 1991 reprint). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Betty Rivard, ed. New Deal Photographs of West Virginia, 1934–1943 (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2012), 143. |

| 3. | Roger May, "Overview," Looking at Appalachia, 2014, http://lookingatappalachia.org/overview. |

| 4. | Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), 46. |

| 5. | Lou Murrey, "Out of Frame: Regional Stereotypes in Photography." Appalachian Voices, December 19, 2015. http://appvoices.org/2015/12/19/regional-stereotypes-in-photography/. |

| 6. | William Schumann, "Introduction: Place and Place-Making in Appalachia." In Appalachia Revisited: New Perspectives on Place, Tradition, and Progress, ed. William Schumann and Rebecca Adkins Fletcher (Bowling Green: University of Kentucky Press, 2016), 9. |

| 7. | David E. Whisnant, Modernizing the Mountaineer: People, Power and Planning in Appalachia (Boone, NC: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1980), 134. |

| 8. | Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 84. |

| 9. | Ibid., 84–86. |

| 10. | Fred Ritchin, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen (New York: Aperture, 2013), 11. |

| 11. | Fred Ritchin, After Photography (New York: Norton, 2009), 70. |

| 12. | Ibid., 75. |

| 13. | Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009), 4. |

| 14. | Ibid., 9. |

| 15. | Jason Huettner, "Capitalist Realism or Poverty Porn?" Hyperallergic, July 7, 2011, https://hyperallergic.com/28555/capitalist-realism-or-poverty-porn. See also Larry Vonalt, "The Dignity of Shelby Lee Adams's 'Disturbing' Family Photography." Studies in Popular Culture 29.2 (October 2006): 110–121. |

| 16. | Shelby Lee Adams, "The Work of Looking." Walk Your Camera, September 7, 2012, http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-shelby-lee-adams-part-one/. |

| 17. | May, "Overview." |

| 18. | Adams, "The Work of Looking." |

| 19. | Ibid. |

| 20. | Roger May, "Looking at Appalachia: Shelby Lee Adams—Part Two," Walk Your Camera, September 15, 2012. http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-shelby-lee-adams-part-two/. |

| 21. | Butler, Frames, 9. |

| 22. | Ibid., 8. |

| 23. | Ibid., 70. |

| 24. | Ibid., 73. |

| 25. | Ibid., 24. |

| 26. | Ibid., 11 |

| 27. | Ibid., 12. |

| 28. | John Alexander Williams, Appalachia: A History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 199. |

| 29. | Williams, Appalachia, 210–211; Horace Kephart, Our Southern Highlanders: A Narrative of Adventure in the Southern Appalachians and a Study of Life Among the Mountaineers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1922, 1984 reprint). See also: Patricia D. Beaver and Helen M. Lewis, "Uncovering the Trail of Ethnic Denial: Ethnicity in Appalachia." In Cultural Diversity in the U.S. South: Anthropological Contributions to a Region in Transition, ed. Carol E. Hill and Patricia D. Beaver (Athens: University of Georgia Press), 51–68; Schumann, "Introduction." |

| 30. | Rivard, New Deal, 2012. |

| 31. | Butler, Frames, 100. |

| 32. | Williams, Appalachia, 204. |

| 33. | Charles Alan Watkins, "Merchandising the Mountaineer: Photography, the Great Depression, and 'Cabins in the Laurel.'" Appalachian Journal 12.3 (Spring 1985): 227. |

| 34. | Williams, Appalachia, 300. |

| 35. | Roger May, "Looking at Appalachia: William Gedney—Part One." Walk Your Camera, July 1, 2012. http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-william-gedney-part-one/. |

| 36. | Roger May, "Looking at Appalachia: William Gedney—Part Two," Walk Your Camera, August 4, 2012. http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-william-gedney-part-two/. |

| 37. | Williams, Appalachia. |

| 38. | Ritchin, Bending the Frame, 49. |

| 39. | Ibid., 50. |