Overview

In this excerpt, editors Scott Romine and Jennifer Rae Greeson introduce Keywords for Southern Studies (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016).

Excerpt

Any collection that aims, as this one does, to represent the upheaval and diversity of a field that is remaking itself must confront at the outset the difficulties posed by that upheaval and diversity. What is "southern studies" today, well into the twenty-first century, in the age of the global-superpower United States? Whatever it is, we think it is mimed by the form of this volume, which does not presume to present a canon, a comprehensive account, or a curated catalog that demarcates the contours of a stable, shared field. Instead, this book contains an idiosyncratic collection of essays on keywords that individual scholars have chosen as particularly critical for the project of southern studies as each of them personally understands it. The result is a collection that is contingent and fragmentary, but capacious enough to hold side by side various disciplinary and theoretical approaches, generational affinities, and intellectual perspectives on an arena of inquiry whose boundaries are constantly being renegotiated.

It is in this very indeterminacy and flexibility that southern studies is becoming an important model for other interdisciplinary intellectual enterprises, perhaps particularly American studies writ large. We realize only too well that just a generation ago southern studies marched obstinately in the rearguard of American studies both politically and methodologically; while we are not prepared to claim that it has leapfrogged fully to the vanguard—indeed the unevenness of the shift is evidenced across this volume—we do believe that its ongoing radical reconfiguration demands broadening notice and broadening participation. At this moment, in this volume, "southern studies" emerges through a process of scholarly definition from the bottom up rather than from the top down. Contributors approach the field through the lens of assumptions and possibilities afforded by single critical terms, rather than by making or subscribing to broad pronouncements about the object or method of the field of study.1 The organization of this collection follows this logic. Although our section headings describe broad family resemblances between terms, neither they nor the "keywords" themselves are intended to approach taxonomic precision. For similar reasons, we have avoided—although some contributors have not—the term "New Southern Studies," which carries, at least implicitly, the promise of a coherent and distinctive effort but whose constitutive features remain contested.

Indeed, it is the almost universally agreed-upon impossibility of making such broad pronouncements that is the hallmark of southern studies today, for it has been reconfigured as an enterprise whose object has become irrevocably obscure. What is southern studies studying? The self-evident answer would seem to be the US South, the self-evident corollary of which is that the US South is neither solid nor exceptional. It lacks an essence (and therefore cannot be known in essentialist terms), a polity, and clearly defined boundaries. Such, at least, are some of the echoing premises of contemporary studies of what has proven to be a slippery object of interrogation.

In a parable told by the Buddha, blind men are brought together to examine an elephant. The results are well known: each grabs a different part and reports a different result. The Buddha then offers his lesson: scholars (the less-remembered subject of the parable) are quarrelsome and disputatious, not to be trusted for an accurate depiction of reality. Whatever its value as an assessment of scholarly temperaments, the parable makes the commonsensical assumption that there's an elephant at the other end of scholarly inquiry: a thing to be known—ideally, at any rate—in ways that are comprehensive and accurate.

South? Ivory Text photograph courtesy of Flickr user Kurtis Garbutt, November 7, 2010. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0. Collage adapted by Eric Solomon. "There's an elephant at the other end of scholarly inquiry: a thing to be known... The field of southern studies, however, seems uncertain of the existence of the elephant."

The field of southern studies, however, seems uncertain of the existence of the elephant, and in some instances actively interested in its demise. In a 2008 review, for example, Leigh Anne Duck calls for a "Southern studies without 'The South'" as a potentially "enlightening" mode of "exiting the realm of our most basic assumptions."2Duck, "Southern Nonidentity," Safundi 9, no. 3 (2008): 329. For scholars such as Duck, the problem with "the South" is precisely the assumptions that have accumulated around it, the conceptual baggage generated by earlier generations of scholarship and popular belief that, arguably, has served to obscure as much as to clarify. As Michael O'Brien has observed in his influential The Idea of the American South (1979), the South itself can be viewed in one of two ways: either as a "solid and integrated social reality about which there have been disparate ideas" or "as an idea, used to organize and comprehend disparate facts of social reality." Opting against the elephant, O'Brien approaches the South as "centrally an intellectual perception . . . which has served to comprehend and weld an unintegrated social reality," observing that the idea of the South "has secured such a hold on the American mind that it is a postulate, to which the facts of American society must be bent, and no longer a deduction."3O'Brien, The Idea of the American South, 1920–1941 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979): xxi, xxii. Although not entirely unprecedented, O'Brien's wedge between the idea of the South and the social reality it purported to represent would prove enabling to later scholars interested in the production, maintenance, and usage of the South as, variously, an invention, an imagined geography, a geographic fantasy, or (in Duck's terminology) "the nation's region."

For many contemporary scholars, the present slipperiness of the US South constitutes a hard-won triumph over the positivist certainties of an early generation of scholarship that, for reasons both historical and institutional, tended to position the South as "Uncle Sam's other province." As Matthew D. Lassiter and Joseph Crespino observe in The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism, "Liberal historians in the postwar decades called for a distinctive southern history based not on a set of empirical differences between region and nation but, rather, on the presumed divergence of a collective southern identity from national myths and American ideals."4Lassiter and Crespino, "Introduction," The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009): 8. For other fields as well, presumptions of southern exceptionalism served as methodological anchors. In a postwar academy flush with resources, southern literary studies coalesced around a set of ostensibly southern senses (of place, community, family, "the concrete") and Faulknerian formulas ("You would have to be born there," "I don't hate it!" "The past is never dead. It's not even past"). Sociological studies of the US South, meanwhile, became institutionalized in the decade in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt identified the region as the nation's "No. 1 economic problem."

Indeed, one solution to any "southern problem"—of which there have been many, from the founding to the present—is to declare it a southern problem, not a national one. Imagined Souths have been used to contain problems ranging from poverty and racial oppression to cultural backwardness and religious fanaticism. But if some monolithic fantasies of the US South have trended toward abjection, others have headed in a romantic direction, imagining the South as a land not of poverty but of resistance to materialism; not of racial oppression but of benign paternalism and noblesse oblige; not of cultural backwardness but of tradition, piety, and bucolic agrarianism. Although scholarly methodologies have tempered their extremes, it is probably fair to say that such fantasies have exerted a persistent force on the study of the US South that, until recent years, has been predicated on difference, especially difference within the nation.

As the solid object of study has receded from us—indeed, as scholars have pushed away from it—its conceptual underpinning has come into focus. "The South" exists only as one side of an implicit binary ("North"/"South") and thus exists always in implied relation—usually antithesis—to what is outside it. Many of the essays collected in this volume seek to disrupt this binary conceptual structure, though contributors use a variety of tactics. Some expose the structure itself and ask how it works and what it is good for; others pursue the multivalent lines of relation between "the South" and terms other than its opposite. The keywords in this volume, then, represent not merely ways to think about the US South but also ways of thinking into and through and beyond it. The question at issue has evolved from "what is southern studies studying?" to "what does southern studies do?"

As the essayists in this volume strip away the mystifying assumption of difference or otherness, they show us what southern studies can do. They train our attention on regimes of white supremacy, labor discipline, and what Colin Dayan has resonantly termed "servile law"—American regimes exemplified by, though never confined to, the southern United States. They illuminate the residues and persistences of interacting peoples and places, markets and material cultures.5See C. Dayan, "Servile Law," in Cities Without Citizens, eds. Eduardo Cadava and Aaron Levy (Philadelphia, PA: Slought Foundation, 2004); The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011). They interrogate new approaches that have broadened the archive and conceptual scope of southern (and American) studies. They investigate the structures of feeling that continue to consolidate and dissolve various Souths, remapping the gap between "real place" and space as it is configured affectively.

Remappings and Keywords. Historic map, "A new and general map of the Southern dominions belonging to the United States of America," 1794, courtesy of Flickr user Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Adapted by Eric Solomon. Contributors "interrogate new approaches that have broadened the archive and conceptual scope of southern (and American) studies. They investigate the structures of feeling that continue to consolidate and dissolve various Souths, remapping the gap between 'real place' and space as it is configured affectively."

As the contributors to this volume exceed the binaristic relation that underpins "southernness," they uncover multiplying, interconnecting webs of relation. They show us that to do southern studies is almost always to work interdisciplinarily: to work in and across a field of intersections and sutures between a geographic, social, economic designation and the products of culture that engage it or something within it. They also show us that to do southern studies is to work transnationally, for beginning from a construct that is defined geographically but not politically invites or requires troubling traditional geopolitical borders by thinking across, within, and between them.

![Urgent America. Flag photograph, January 24, 2009, courtesy of Flickr user Beverly and Pack. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0. Adapted by Eric Solomon. "Many of [the essays] share a note of urgency." Urgent America. Flag photograph, January 24, 2009, courtesy of Flickr user Beverly and Pack. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0. Adapted by Eric Solomon. "Many of [the essays] share a note of urgency."](https://i0.wp.com/southernspaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/keywords-007-amflag.jpg?ssl=1)

This geopolitical frame brings us to a final critical consonance among the essays in this volume. Many of them share a note of urgency, an urgency directed not toward the loss of the object of study or the ambiguous state of the field but rather toward the present moment. Americans today stand as citizens of a unilateral global superpower without—from the perspectives of many involved in this work—possessing an honest or realistic sense of what the United States is, what it has been, and thus what it could become. This ignorance, whether willful or not, is underwritten by the persistence of monolithic fantasies of the US South—fantasies that continue to inflect the cultural production of space in the United States in this era of global unilateralism, producing feedback loops that exceed (as they always have) the borders of the nation. Doing southern studies is undoing the monolith by—in the words of one essayist in this volume, Shirley Elizabeth Thompson—"pursu[ing] a radical interdisciplinarity" forged from "critical and contingent methods and theories" and "more precisely articulating the disruptive knowledge of subalterns." Doing southern studies is unmasking and refusing the binary thinking—"North"/"South," nation/South, First World/Third World, self/other—that postcolonial studies has taught us is the most damaging rhetorical structure of empire.6Particularly Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978) and Sara Suleri Goodyear, Rhetoric of English India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). Doing southern studies is thinking geographically, thinking historically, thinking relationally, thinking about power, thinking about justice, thinking back.

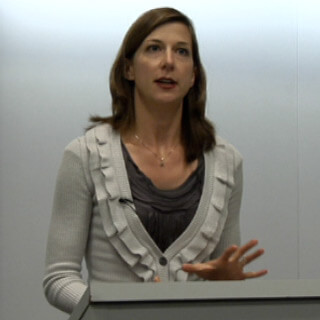

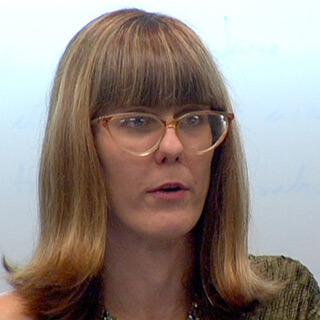

About the Authors

Scott Romine is professor of English at University of North Carolina Greensboro. His publications include The Real South: Southern Narrative in the Age of Cultural Reproduction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Universiy Press, 2008). Jennifer Rae Greeson is associate professor of English at University of Virginia. Her publications include Our South: Geographic Fantasy and the Rise of National Literature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010).

Cover Image Attribution:

Ivory Text photograph courtesy of Flickr user Kurtis Garbutt, November 7, 2010. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.Recommended Resources

Text

Duck, Leigh Ann. The Nation's Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Goodyear, Sara Suleri. Rhetoric of English India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Lassiter, Matthew D. and Joseph Crespino, eds. The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

McKee, Katheryn and Annette Trefzer. "Preface: Global Contexts, Local Literatures; The New Southern Studies." American Literature 78 (2006): 677–690.

Ring, Natalie J. The Problem South: Region, Empire, and the New Liberal State, 1880–1930. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Web

Bibliography Narrative. New Southern Studies/ Global Souths. The University of California Santa Barbara. https://hemsouths.english.ucsb.edu/?page_id=53.

The Center for the Study of Southern Culture. The University of Mississippi. http://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/about/mission/.

The Institute for Southern Studies. The University of North Carolina. http://www.southernstudies.org/iss/about.html.

Schwarz, Benjamin. "The Idea of the South." The Atlantic, December 1997. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1997/12/the-idea-of-the-south/377028/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | The organization of this collection follows this logic. Although our section headings describe broad family resemblances between terms, neither they nor the "keywords" themselves are intended to approach taxonomic precision. For similar reasons, we have avoided—although some contributors have not—the term "New Southern Studies," which carries, at least implicitly, the promise of a coherent and distinctive effort but whose constitutive features remain contested. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Duck, "Southern Nonidentity," Safundi 9, no. 3 (2008): 329. |

| 3. | O'Brien, The Idea of the American South, 1920–1941 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979): xxi, xxii. |

| 4. | Lassiter and Crespino, "Introduction," The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009): 8. |

| 5. | See C. Dayan, "Servile Law," in Cities Without Citizens, eds. Eduardo Cadava and Aaron Levy (Philadelphia, PA: Slought Foundation, 2004); The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011). |

| 6. | Particularly Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978) and Sara Suleri Goodyear, Rhetoric of English India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). |