Overview

This essay considers southern literature in terms of generic forms that are, if not uniquely southern, substantially recognizable as contingent upon southern identifiers: geographic, social, cultural, as well as historical and linguistic contingencies that constitute "the South."

Introduction

"Southern literature" announces the conjunction of the US South and an expressive art — texts identified as belonging to a particular history, social organization, and cultural imaginary. In defining a text's "southernness," the matter of its genre might not seem a touchstone of much value. To some, genres are universal categories that describe formal literary conventions, not geo-social preoccupations. Yet, the South can be said to have its own literary genres — its particular sets of forms or organizing motifs — as much as it has a history and manners. An overview of southern literature based on a selection of key genres departs substantially from the program of traditional literary histories, which rely upon relatively static, periodic, historical reference points to arrange and provide nomenclatures for southern literature. This tradition is not without irony, given the other directive that has long governed southern literary study: the emphasis on promoting "internal" or a-historical, non-contingent readings of texts. Anthologies and critical surveys usually gather works into groupings that emphasize specific time and history bound periods: antebellum, post-bellum, the "renascence" (equated with the "modern" or "the period between the two wars"), and most recently the post-modern, all the while insisting upon the importance of essentialized form over topical circumstance. The present essay stresses the organizational forms, motifs, and stylistic conventions that can delineate the shape and presentation of a text (the text's genre, in other words) but also understands these matters as inevitably representing and promoting specific versions of culture. The claim to order that is presented here highlights selected genres indelibly associated with the South: the plantation novel, the slave narrative, southwestern humor, southern pastoral and "counter-pastoral," southern modernism, the southern grotesque, and yes, even "grit lit."

Genre in Relation to History and Historical Coverage

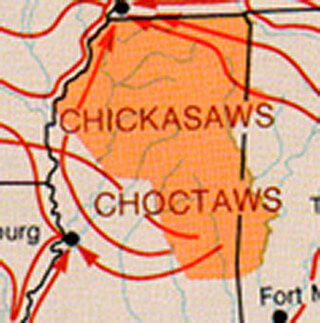

Southern literature is substantially recognizable as contingent upon certain identifiers: geographic, social, cultural, political, as well as historical and linguistic contingencies that make up what is known and named as "the South." Of course history remains a core emphasis in this arrangement, but to think of southern writing in terms of its organizational forms and features instead of its chronological appearance also shifts the grounds of historical emphasis. For instance, to group southern literature under the headings "antebellum" and "postbellum" makes the Civil War the great rationale of literary production. However, if we look at nineteenth century southern literature under the headings of thematic or stylistic or plot-oriented genres that authors chose during the time, what we see is that the South's race-based institution of slavery was the driving force behind literary production. A southern slavocracy, sectionalist and ultimately nationalist, is what called into being the first, and in many ways most distinctively southern genres. Slavery and the racial divisions it enforced by law and custom resulted in a multitude of literary forms of response, engagement, and argument: from the plantation novel to the slave narrative; from the slave narratives of the 1830s to the neo-slave narratives of the 1980s and '90s; from the "anti-Tom" novels crafted in response to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin down to such blockbuster historical epics of the Civil Rights Era as Alex Haley's Roots, Ernest Gaines's The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and Margaret Walker's Jubilee.

To claim that there are "southern" genres of literature might seem to divorce the South's writing from some larger concept of value, and indeed southern writers have chafed under the sectional or regional label, regardless of how the term "southern" was being applied to their productions. In delineating generic headings, the overview that follows is not a "historical coverage" model. Any arrangement that a literary historian might choose results in inclusions and exclusions based on both literary and political ideologies that privilege certain values—and certain literary forms or discourses—over others. The preference that an overview of southern literature by genre asserts is that of forms, motifs, and conventions, but this preference also reflects the current theoretical argument that genres are codes constructed from, as well as speaking to, historical contingency. The rubric "southern" has meant different things to differently identified groups at different times. The literary label "southern" asserts its various meanings in part through the distinctive sets of works we can find that practice similar modes of expression, organization, and motive—in other words, genres.

Genre and Southern Genre Definitions

Top, Cover to the Southern Literary Messenger, published in Richmond, Virginia. Edited and published by Thomas W. White, February, 1837. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom, Table of contents to the Southern Literary Messenger, December, 1835. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Images are in the public domain.

We might begin to address definitional questions by noting that southern literature is itself a genre: a body of texts bound together and meeting expectations of readers through similarities in areas of theme, setting, mood, message, structure, plot etc. The first southern literatures and indeed the first critical pronouncements about southern literature appeared at a time when the South, as a section of the United States, was beginning to understand itself in terms of cultural and political difference—in terms of what its way of life was not, and what it was positioned against. In the 1830s, the North argued for this sense of difference from without, through abolitionist societies and popular writing that began to flood media outlets. One of the earliest statements of what southern literature needed to be and to do was announced in one of the section's first literary journals, the Southern Literary Messenger. Its inaugural 1834 issue called for southerners to support a distinctly southern, i.e. not northern literature. By 1856, in much more strident tones, the Messenger was dictating "The Duty of Southern Authors" in an editorial. Beginning in the 1830s, northern writers and readers were busily creating assumptions about the South’s difference, and writers and readers of the South correspondingly defined themselves against the place (the North) or the ideology (Anti-Slavery, Industrial Capitalism) that they saw themselves as different from. Then and now, insiders and outsiders involved in the dynamics of writing about place have both shaped and relied upon types, themes, and conventions that come to define particular places as well as modes of expression. The ideological as well as artistic processes that identified the first southern genres continued to do so throughout the twentieth century, from the Southern Agrarians' revolt against a national urban-industrial complex in the 1930s, embodied in pastoral forms, to the anti-establishment, anti-"Southern Living" agendas of self-identified Poor South writers of recent times, embodied in what we have come to call "Grit Lit."

Genre and Ideology

The work of genre construction is to categorize texts according to shared features of content or structure or stylistic conventions or rhetorical function. From The Southern Literary Messenger to The Companion to Southern Literature (2002), scholars and readers have looked for ways to differentiate southern literature from that of other places (including American literature, itself conceivably a sectional genre) by identifying these features. If we go back fifty years, we find in Robert Heilman's essay, entitled "The Southern Temper," a seminal exercise in genre making (it was first published in 1952 in Louis Rubin and Robert Jacobs, Southern Renascence, and was reprinted in 1961 in Rubin and Jacobs', South: Modern Southern Literature in its Cultural Setting). Heilman identified five features of the southern literary mind that made for distinctively "southern" texts based on analysis of what he considered to be the important fiction of the modern period, and these qualities directed the reading of southern literature for a generation.

The quest to classify the literature has continued unabated for the last half-century, although critics have disagreed vigorously over where to look for the distinguishing conventions that allow the assignment of genre identification to texts. In today's critical climate we understand that, as Thomas Beebee (in The Ideology of Genre (1994)) tells us, all genres are ideological. William Gilmore Simms, when he wanted to attack Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, wrote scathingly not of her abolitionist argument but of how she had transgressed against the limits of the historical romance. When the Southern Agrarians wanted to protest the excesses of the capitalistic machine and the soul-killing effects of scientific dominance, they wrote one manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand. However, the more productive and effective channel for their cause was their championing, in dozens of critical studies and in their own poems and novels of a mythologically, instead of a historically, ordered past. They invoked an ideal of communal memory in order to rebuke the disordered present, an agenda that identifies their productions as pastoral, a genre defined by its practitioners’ intention to provide social critique within clearly defined literary conventions.

Genre: Similarity and Difference

The selection of southern genres outlined in this overview indicates one more key element of the genre approach: genres classify works according to similarities, but they thrive and depend upon difference, not only differences in conventions and forms, but differences in the ways that groups within the same geographical places experience history. From the slave South came the radically different genres of slave narrative and plantation romance. The agrarian South produced both pastoral and anti-pastoral. Self-conscious, southern Renascence writers produced both what we might call an establishment modernist narrative and, as counterforms, the grotesque narrative and the "grit" narrative. Two other categories of genre differentiation are not discussed in this overview: the splitting off or subdividing of women's and African American literature. Considering African American and southern women's literary history apart from that of white or white male writers has been responsible for sometimes meaningful, but often arbitrary and misleading, exclusionary readings. Women’s literary versions of southern history and culture resulted in their adaptation of some traditionally male genres and their creation of others. We can speak, for instance, of the mother/daughter genre of southern fiction. Yet certain splits—including the division of plantation literature into the male romance and the female domestic novel—resulted in artificial barriers to the understanding of common imagery and intention.

loc.gov/pictures/resource/van.5a52142.

Likewise, to segregate white southern literature from African American literature means that we are perpetually looking, half-dimensionally, at only one side of a coin. For example, two historically contingent literary "renaissances" grew out of southern experience in the early twentieth century: the Harlem Renaissance and the Southern Renascence. As differently "placed" as they might seem from the designations "Harlem" and "Southern," the literatures that are categorized within these separate concepts of "flowerings" share many of the same historical contingencies. One has only to read John Crowe Ransom's "Antique Harvesters" and Jean Toomer's "Harvest Song," both of them key expressions of an artistic impulse embedded in southern history, to see how important it is to look across categories that separate literary studies. Genre divisions potentially can highlight meaningful differences or obscure or distort them, so any useful classification by genre must address how literary categories speak to one another. Inclusive genre study tells us about many souths. We can use genre classifications to collect southern histories reflected in sectional and regional literary conventions, and from genres we can learn many ways to read the incredibly rich and diverse worlds that three centuries of writing in and out of the US South represent.

Organizing by Genre: Scope and Limitations

The cultures of several souths are embedded in literatures of slavery, literatures of pastoral, and literatures of resistance. In gathering examples of these different organizations, it is not surprising that most of them come from fiction and autobiography, which tend to be constructed from social dynamics and structures that follow the narrative flow of history. Although this overview does not attempt to use poetry and drama very extensively for illustrations, certainly both genres furnish examples of each of the categories that we will follow, and indeed for the Southern Agrarians, poetry was a primary vehicle. A different question concerns the idea of "the southern poem" as a genre. Invited Guest: An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Southern Poetry (University of Virginia Press, 2003), makes the positive case with a large gathering of representative poems. Four essays that also consider this question are:

David Kirby, "Is There a Southern Poetry?" Southern Review 30 (1994): 869-880.

Dave Smith, "There’s a Bird Hung Around My Neck: Observations on Contemporary Southern Poetry." Five Points 1 (1997): 115-142.

Dave Smith, "Cornering the Southern Poem." Southern Review 30 (1994): 643-49.

Ernest Suarez,"Contemporary Southern Poetry and Critical Practice." Southern Review 30 (1994): 674-688.

While the place and function of a spatially defined southern poetry is beyond our scope here, the four essays listed above provide a compelling argument for the idea that such a genre exists, and the same case might be made for a genre of southern drama. See, for instance, Kenneth Holditch's Tennessee Williams and the South (University Press of Mississippi, 2002), and Charles S. Watson's The History of Southern Drama (University Press of Kentucky, 1997).

Another important discussion that needs to take place concerns the question of the place of Appalachian literature within a southern literary history. Valuable anthologies include Voices from the Hills: Selected Readings of Southern Appalachia (1987) edited by Robert J. Higgs and Ambrose N. Manning and its sequel, Appalachia Inside Out: A Sequel to Voices from the Hills (1995), eds. Higgs, Manning and Jim Wayne Miller; and Bloodroot: Reflections on Place by Appalachian Women Writers (2000), ed. Joyce Dyer.

The South's Literatures of Slavery

(Slave Narratives, Plantation Fiction, Civil Rights Epics, and Neo-Slave Narratives)

The American institution of chattel slavery began with the first importation of captured Africans in the 1620s and did not end until the Confederacy's surrender in 1865. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, slavery's legal practice was confined mostly within the plantation South. The system of national and state laws that were developed to organize and control this racially defined, captive labor force was augmented by systems of social codes that regulated how white slave owners, African American slaves, and non-slaveowning whites behaved across race, class, and gender lines. Northerners developed their own understanding of these interactions, and the literature that was written on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line began to be shaped as responses across ideological as well as sectional borders.

White novelists of the southern states began in the 1820s to develop the plantation setting as an idealized literary world populated by characters who developed into types, each expected to convey a set of personal qualities—virtues or vices—as well as to act according to fixed mannerisms of dress, gesture, and language. Gender codes also developed for plantation writing as both northern and southern women entered, and finally took over, the marketplace for popular social fiction. Often the plantation literature by men was considered to belong to the genre of the historical romance that used Sir Walter Scott's works as a model, while women's writing came to be viewed under the heading of "sentimental" or "domestic" fiction. In the plantation fiction by writers of either gender, slavery itself was seldom foregrounded in any obvious way. However, if we examine the class constructions on which such fiction’s plots are based, we see that the planter aristocracy was the center of social organization for both the "male" historical romance and the "female" domestic novel. At least implicitly, and often directly, these works of both genders were promoting model slave societies founded upon the plantation ideal of patriarchy. The white belles and matriarchs enshrined in domestic plantation Arcadies and the cavaliers whose horses are curried and armaments carried by "sable body servants" are iconic endorsements of a social system and emerging nationalism operating on the backs of usually silent, often invisible black "dependents."

While white writers in the South were looking to the plantation to provide the most fertile ground for fictions representing their socioeconomic ideals, ex-slave, African American writers during the same period used the plantation scheme very differently in developing what might be seen as America's first indigenous literature: the North American slave narrative. An ironic factor in the production of these narratives can be noted in the generic title "Fugitive Slave Narrative" now often given to these works. Southern-born narrators, telling firsthand of their experience of slavery, could become authors only by escaping both the South and the condition. In their narratives they had to return to the world that enslaved them, and were called upon to provide accurate reproductions of both the places and the experiences contained within the past they had fled. This genre was tightly bound within conventions designed to accomplish anti-slavery goals (as indeed, plantation fiction was bound to legitimize the world the slaveholders had made). The "formula" of the slave narrative was something that the ex-slave writer understood only too well. Today we can acknowledge some features of the genre that represent the ex-slave writers' chafing against the genre rules as well as their attending to them.

Bottom, Cover of The Conjure Woman, a satire of plantation fiction (Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1899). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Images in public domain.

Slavery generated northern writing as much as southern, and the North's most eloquent literary writer on the subject, Harriet Beecher Stowe, stimulated the production of plantation fiction in the South, especially in the form of a specialized sub-genre designed specifically to answer her attack on slavery in Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). Stowe drew upon specific details and situations that she took directly from several slave narratives, but she also found her own form, combining epic, realism, sentiment, and jeremiad to reach the largest reading audience that a novel had ever produced in America. In response, "Anti-Tom" novels by the dozens modeled their plots and characters on Stowe's creations, reproducing a format that remained effective even after the Civil War decided the questions she had raised.

Uncle Tom's Cabin provided for writers a hundred years later some key features, in detail and scope, that African American writers in particular drew upon to relate slavery to the message of the Civil Rights Era in the 1960s and 1970s. The epic historical novel, exemplified by Alex Haley's Roots, traced the freedom struggle back to its historical beginnings in the middle passage and the cotton and rice plantations of the Old South. Like Stowe's novel, these works offer emotional dramatizations of slave life within a sweeping episodic structure designed to convey both a sense of past history and present urgency.

The slave narrative genre, like Stowe's novel, has continued for over a century to generate fiction that draws upon its distinctive formal features. Beginning in the 1970s, writers as disparate as Ishmael Reed and William Styron, Octavia Butler and Charles Johnson have brought the first-person slave narrator's voice into dialogue with modern practices of racial discrimination through the genre of "neo-slave narrative."

The categories enumerated below reflect the great variety of literature produced out of the fugitive-slave and slaveowning South, beginning within the period of 1820 to 1865 and extending down to the present. In each genre we see how persistently the South's identity, within and beyond its literature, was formed by and remains tied to its "peculiar institution" and its moment of attempted nationalism.

The Slave Narrative

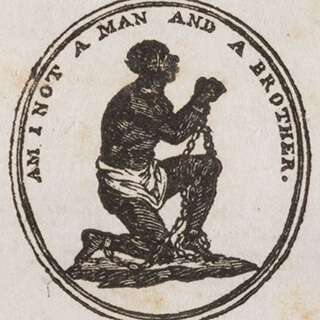

Top, Dutchess County Anti-Slavery Society notice, April 22, 1839. Pleasant Valley, New York. Courtesy of the New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/620a1a3f-1f80-4bd1-e040-e00a18060c9d.

Bottom, Anti-slavery Liberty Bell print, Boston, 1848. Engraving by J. R. Foster. Published by National Anti-slavery Bazaar. Courtesy of the New York Public Library Schomburg Center, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-75d7-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

The North American Slave Narrative began as a rhetorical form commandeered by the abolitionist movements in both Great Britain and America. Over a hundred of these stories of escape/pursuit/finding freedom, published between 1760 and 1865, have been identified. The rhetorical situation was well-defined: freed slaves or those who had escaped their owners were asked to tell of their experiences within bondage, emphasizing trials and tribulations, the cruelty of masters, the depths of their suffering, and the strength of their desire to be free. Slave narratives were potent weapons in the abolition arsenal, especially with the rise of organized abolition societies in the 1830s. No other rhetorical design had as much power as these eyewitness accounts to move opinion against the institution of slavery. The slave had endured what others could only imagine, and in his/her search for freedom struck a deep chord of sympathy in readers who saw themselves as guardians of the ideal of liberty for "all men."

Accuracy in the slave narrative was paramount. The few fictionalized accounts, when discovered, provoked accusations from the South's defenders that all of these publications were suspect. Thus the factual accounts almost always included extensive prefatory endorsements from well-regarded white sponsors. The slave narrator him or herself was encouraged to leave inner revelations, such as expressions of self-discovery and individuality, in the background and to foreground the verifiable facts of representative slave experience, without adornment.

Today we recognize in slave narratives both their didactic function as evidence in the abolitionists' cause and their artistic and expressive functions for the slave author whose identity as writer was especially ambiguous. The slaves' claims to humanity, to authority, to self-determination were enacted in taking up pen and paper, yet the tale to be told was pressed into a conventional format, and the generic plot returned them to the status of chattel. "You have seen how a man was made a slave," claimed Frederick Douglass in the 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave that has become the paradigmatic work for the genre. "You shall see how a slave was made a man." In the best of the narratives, such as Douglass's, the writer finds ways, through imagery, style, and voicing, to affirm selfhood and creativity within the prescriptions but often against the expectations of readers of the time.

Most of these narratives were produced during the first great era of American literature (1830–1860), side by side with such classics of American self-fashioning as Thoreau's Walden, Whitman's Leaves of Grass, and Melville's Moby-Dick. Once Stowe had published Uncle Tom's Cabin, Douglass (in his 1855 My Bondage and My Freedom) and Harriet Jacobs (in her 1861 Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl) adopted novelistic techniques such as extensive dialogue between "characters" and thematic chapter headings. One especially intriguing example of the novelization of the slave narrative has been uncovered by Henry Louis Gates. In 2002 he re-published a novel by a slave woman probably named Hannah Crafts, entitled "The Bondwoman's Narrative," first published, again probably, in New Jersey sometime between 1853 and 1861. The narrative is named fiction and uses many fictional elements (including "borrowings" from Charles Dickens). Gates has pieced together fascinating speculations concerning the African American woman who wrote the fictional account of a slave woman's life and her final attainment of freedom. The definitive study of this genre is William L. Andrews's To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760–1865. He chose for inclusion in his study "all the forms of first-person retrospective prose narrative that came from the mouths or pens of American blacks between 1760 and 1865."

Plantation Fictions

The Historical Romance and the Domestic Novel. Plantation fiction as a rubric for southern literature has often included, even emphasized, literature written by local color writers after the Civil War. Yet we will be considering that grouping in a different light because its use of the "trappings" of the plantation served purposes related to the Reconstruction South's racial agenda, and not the institutionalization of slavery itself. The plantation fiction described below belongs to the antebellum period and was ideologically motivated to render a vision of southern society as a slavocracy in all its relations. Considerations of southern men and women’s fiction of this period have traditionally run on very different tracks. The novels of the early nineteenth century were often labeled "romances" by the men who wrote them (George Tucker, John Pendleton Kennedy, William A. Caruthers, and William Gilmore Simms). These works usually dealt with very specific historical moments (Bacon's Rebellion, the Revolutionary War) and stressed what has become known as "the cavalier myth" which touted the heroics of aristocratic types. The plantation was most often a backdrop, but a crucial one—a credential indicating the nobility of class that paralleled the nobility of spirit that the heroic male character must exemplify.

In both the mid-nineteenth century North and South, women writers were not long in entering the book-writing business. Their works almost always bear the labels "domestic" or "sentimental," and those labels have usually been pejorative. The labeling of women’s fiction as "domestic" reflects the idea that women belonged in the home, that politics and public life were inappropriate for women, and that their natural "sphere" was to inculcate, in their children, the morals needed for gendered roles in society. True to form, white women’s writing in the plantation South created stories of women that centered on "the marriage plot," turning belles into mistresses of the house who know and do their duty. Still it is important to see, in southern white women's antebellum fiction, the political value of the plantation as a social organization involving the ideal of slavery as a "domestic institution." Caroline Hentz, E.D.E.N. Southworth, Caroline Gilman, and Augusta Jane Evans Wilson were interested in white upper-class women's experience within this ideal of planter society, just as the male romancers were interested in upper-class masculinity within the same paradigm. The fictional worlds of both white southern men and women writers privileged the lives of slaveholders, even if plantation settings and slaves are seldom center-stage. Caroline Gilman's Recollections of a Southern Matron (1837) and John P. Kennedy's Swallow Barn (1832) are the most explicit of this genre in exploring directly the workings of the plantation as a theme. In these novels the plantation is the ideal home, where slaves and slaveholders are part of one patriarchally ordered family that combines economic and social responsibilities. African American writers Frederick Douglass, in The Heroic Slave (1853), William Wells Brown in Clotel or The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States (1853), and Frances Watkins in fictional narratives such as "The Slave Mother: A Tale of the Ohio" (1856) rebuke the genre and gender positions of plantation literature in dramatic ways, appropriating virtues associated with the cavalier hero and the plantation belle for African American characters who actively work against or who are victims of the slave system.

The Anti-Tom Novel. Before the last installment of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin appeared in The National Era in 1851, and before the ink was dry on the book version that came out in March of 1852, southerners were sharpening their pens into knives. The South found no shortage of writers of both genders eager to refute Stowe's villainization of slave owners and her romantization of slaves. Dozens of works of fiction and epic narrative poems were published in counter-attack before the end of the Civil War. For many years after the war had settled the book's major question, white southerners continued to try to undo the damage to their social image that her novel had inflicted. John P. Kennedy and William Gilmore Simms, the South's two most well known romancers, might be said to have anticipated Stowe more than directly confronted her. Kennedy brought out a second edition of his popular plantation work, Swallow Barn, in 1852, adding a chapter in which the kindly master details his plan to make slavery, a necessary evil even to him, more equitable for the slave. William Gilmore Simms's Woodcraft was published (originally as The Sword and the Distaff) only a few months after Uncle Tom's Cabin's debut in book form, but it contains some discussions that are clear refutations of Stowe's views. Set at the end of the Revolutionary War, Woodcraft embellishes the career of a colorful character, army officer Captain Porgy, to develop a plot hinging in part on the master's close relationship to his manservant (notably named Tom).

In 1854 appeared two of the most significant novels to directly take on Stowe's arguments: Thomas B. Thorpe's The Master's House and Caroline Hentz's The Planter's Northern Bride. Two of the most popular and sentimental as well as unrealistic Anti-Tom novels were Mary Eastman's Aunt Phillis's Cabin (1852) and Maria McIntosh's The Lofty and the Lowly (1853), which contained the telling sub-title, "Good in All and None All Good." Slaves in the Anti-Tom works are generally the happy, singing, childlike stereotypes that Stowe herself helped to cement, yet sometimes, as in The Planter's Northern Bride, there are portraits of evil, rebellious servants who plot insurrection and murder. The vision that these novels promote is of a South in which slaves and masters enjoy a mutually supportive, familial bond that is only severed by the ignorant or greedy machinations of abolitionists. The North's capitalistic labor structure is indicted, while the master is cast as the enlightened descendant of the southern heroes of the Revolution, and the guarantor of the rights of (land and slave owning) man. None of the refutations had anywhere near the persuasive impact of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Yet the huge popularity of an early twentieth century southern novelist, Thomas Dixon, who followed Stowe's footsteps as a master propagandist, reflects an ironic, even tragic, shift in public will. Thomas Dixon made use of many of Stowe's effective fictional and rhetorical strategies in his white supremacist novels, works such as The Clansman (1905) and The Leopard's Spots (1902) that found wide audiences, especially when D.W. Griffith transformed them into the landmark film Birth of a Nation in 1915.

The Civil Rights Epic

Of the many literary works that grew out of the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 70s, one interesting group is the epic novels that return to slavery for plots and characters in order to give the struggle for African American political freedom and socioeconomic justice an extensive historical dimension. African American writers Margaret Walker in Jubilee (1965), Ernest Gaines in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971), and Alex Haley in Roots (1976) published sweeping historical novels that covered the freedom struggle across generations beginning with a realistic portrayal of their heroes' early lives in slavery. A forerunner to these is Arna Bontemps's 1936 novel, Black Thunder, which drew upon Gabriel Prosser's abortive slave rebellion near Richmond in 1800. Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon (1977) and Beloved (1987), as well as Gloria Naylor's Mama Day (1988) and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1992), continue the Civil Rights Era interrogation of the American promises of freedom and equality when they implicitly reference contemporary situations of struggle within plots of slave experience. William Styron argued that his novel The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) grew out of his own personal wrestling with civil rights issues. As a narrative cast within the first-person voice of the slave Nat Turner, Styron drew, as did the writers considered below, upon the slave narrative form, although his novel shows much less awareness of the original slave narratives than do other neo-slave narrative fiction writers.

The Neo-Slave Novel

Neo-Slave Narratives are first-person fictional novels that adopt the form of the pre-Civil War, first-person retrospective slave narratives. Like the civil rights epics, they have grown primarily as a response of African American writers to the 1960s political struggles for equal opportunity. Some of these novels are set completely within the historical period of slavery, while others use features of science fiction time travel (Octavia Butler's Kindred (1979)) or magic realism techniques allowing fantastic, often anachronistic plot elements (Charles Johnson's Oxherding Tale (1982); Ishmael Reed's Flight to Canada (1976)). The neo-slave narratives are usually very self-conscious in their imaginative borrowings of the actual slave autobiographies, which constitute a kind of parent form for all African American literature. Ishmael Reed's Flight to Canada, for instance, directly references the narrative of Josiah Henson, one of the sources that Stowe appropriated for Uncle Tom's Cabin. William Styron's Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) draws from the wording of the slave revolt leader's Confession, taken from and published by his lawyer after the 1831 revolt. Styron's work, a white writer's appropriation and fictionalizing of a major African American figure's life, was very controversial. African American writers and critics objected strongly to Styron's lack of research into the actualities of slave life and more particularly to his distortions of the known facts of Turner's life. The Confessions of Nat Turner heightened the awareness both within and beyond the African American community of the need for well-grounded efforts to recover and interpret the slave's experience in history and literature. Sherley Anne Williams's novel Dessa Rose (1986), in response to what she called Styron's "travesty," took up this challenge with a plot that follows the life of a woman slave who, after an unsuccessful slave rebellion, is able to escape and take charge of her life. The neo-slave narrative celebrates the forceful witness of the fugitive slaves, particularly their will to freedom and their courage in escaping and confronting oppressive, racist institutions, and applies their perspectives to contemporary African American life.

The South's Literatures of Pastoral

(Local Color, Civil War Literature, Southern Agrarianism, Southern Modernism)

The rural ordering of southern life well into the twentieth century influenced many of its ideological positions, and these positions in turn made the classical genre of pastoral a congenial form for many southern writers. The pastoral is a genre that, standardized by Virgil in his Eclogues, served writers seeking to resolve the tension between memories of a simpler past, associated with nature and rural society, and experience in a more complex present world. Pastoral literature historically has flourished in times of dramatic change. Writers undergoing a dislocation from a familiar home world turn to the conventions of the pastoral to envision that simpler locale from the vantage point of inevitable loss and removal. In pastoral, then, the past looms large, not so much as a particular historical time and place as an idealized, mythologized lost realm (such as Virgil's Arcadia). The past of pastoral is associated with the natural world (imaged as the "good earth" or "the garden") and with community (shepherd and flock, extended family, village, or homeland). However, such a version of the past tends inevitably towards nostalgia and fatalism, and potentially towards paralysis. In the South the idealization of the rural past is made even more dangerous, and more complicated, because the white South's Arcadia was predicated upon slavery.

The pastoral became a congenial genre for southern writers even before the Civil War, in large part through its ties to agrarian idealism. Thomas Jefferson's 1780s invocation, in Notes on the State of Virginia, of the "cultivators," those who "till the earth" as "the chosen people of God," was his attempt to stand against the encroachments into his idyllic Virginia of the trade and manufacturing economy that was already enlisting the enthusiasm of northern colonies. In the next century, John Pendleton Kennedy's Swallow Barn (1832) was the evocation of a city dweller (a Baltimore businessman and lawyer) who created a James River plantation setting both to praise and satirize the country life of his childhood. Both Jefferson and Kennedy lived in the whirlwind of a complex, changing South, far removed from the cultivators they idealized, with intentional or unintentional irony, in their writing. Herein lies the impetus of the pastoral: its creation of the rustic inhabitants of the good earth always grows out of a consciousness steeped in the effects of inevitable change and displacement. The garden is a lost paradise whose primary use, as image, is to mount an exile’s critique of the complex, urban world caught up in dramas of historical force and social upheaval.

For the last twenty years of the twentieth century, literary critics tried to move beyond a famous (now infamous) pastoral pronouncement of Southern Agrarian Allen Tate, a comment that became the defining statement of southern literature’s thematics from the 1940s to the 1980s. With the end of World War I, Tate intoned, "the South reentered the world—but gave a backward glance as it slipped over the border" ("The New Provincialism." 1945. Essays of Four Decades. Chicago: Swallow, 1968. 535–546). Beneath Tate's singling out of World War I as a dividing line responsible for a pastoralized literary consciousness was an awareness of the Civil War as another cataclysmic moment of change and separation responsible for summoning up, in some southern minds, the "backward glance." Tate and the Vanderbilt Fugitives, forming their poetic as well as social credo in the 1920s, wanted nothing more than to distance themselves from the literature of the "post-Confederacy," the canon of the "Lost Cause," that memorialized the South’s forced re-entry into the Union. The complex literature of the Fugitive-Agrarians (Tate, John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren, Donald Davidson) and Southern Modernists (epitomized by William Faulkner) explores, with more guilt, tension, and ambivalence, the emotions of pastoral that we recognize in earlier, and especially white male local color, writers. In their tendency to return to a mythic past, we can connect the more ironic response of Southern Renascence writers to the responses of Local Colorists publishing in the years following "Surrender" and novelists from that time forward who have used the Civil War as the specific historical dividing line between ideal past and real present. Local Color, Civil War, Agrarian, and Modernist classifications of southern literature all involve evoking a sense of loss through the allure of the threatened natural environment and juxtaposing fading ideals of the past against painful realities of the present.

Local color writers of the South were encouraged by northern markets to make plantation and village southern settings into the "good lost land" of pastoral, in part to satisfy the longings of readers increasingly removed in the late nineteenth century from any real experience of country life. The plantation was mythologized in local color writing more than it had been in antebellum fiction, with slavery ironically now an acceptable feature of the idealization. Following World War I, southern writers confronted historical pressures forcing the South irrevocably from its rural and agricultural base. Certainly in relation to immediate post-Civil War writers, these modern writers saw the past through a glass darkened by shades of guilt and irony that are missing in some Local Colorists, who were trying to win with their pens the war that had been lost at Appomattox. Nevertheless, the tension between mythologized past and diminished present that characterizes all pastoral is embodied in southern writing of many different places and times: from Jefferson's Monticello and Kennedy's tidewater Virginia, to Grace King's New Orleans and Joel Chandler Harris's middle Georgia, to Ellen Glasgow's Civil War battle grounds and Faulkner's mythical Yoknapatawpha County, to Jean Toomer's Georgia and Zora Neale Hurston's south Florida. It is a tension involving the ominous threat of change in southern locales that always function only precariously and ambivalently as havens held sacred out of time.

See Lewis Simpson, The Dispossessed Garden: Pastoral and History in Southern Literature (Louisiana State University Press, 1975), and Lucinda MacKethan, The Dream of Arcady: Place and Time in Southern Literature (Louisiana State University Press, 1980).

Local Color

Southern writers, particularly after the Civil War, saw the advantage of devising a literary agenda to advance a political one and found in local color writing a successful formula for this program, especially during the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction era, roughly from 1870 to 1920. Southern white writers, both men and women, made local color fiction a convenient tool for insinuating racial paternalism into pastoral evocations of a traditional society of the past. Popular taste dictated many of the properties of the genre: quaint locales, attention to details of dress, manner, and speech, colorful vernacular dialects, marriage plots which both highlight and overcome difference (between families, classes, and regions). Many of the most popular local color works of white male writers (Thomas Nelson Page in In Ole Virginia (1887), Joel Chandler Harris in his Uncle Remus tales (1880), James Lane Allen in his many short stories) used the mechanism of the frame narrator who speaks in a detached, non-vernacular voice that controls the portrayals of quainter but also less sophisticated narrators in the "inside" story. The double structures are designed to highlight the gap between simple and "peculiar" or exotic folk, colorful and sympathetic though they may be, and the educated, realistic, framing voice that the reader has no choice but to accept as a higher authority. Herein the pastoral tension between the sophisticated man of the world who takes the backward glance and the rural rustic who has been left behind meet within a dual (and dueling) narrative structure. White women writers often promoted the same white paternalism (Sherwood Bonner in her Dialect Tales (1883), Grace King in stories such as those collected in Balcony Stories (1893), Eugenia Jones Bacon in Lyddy (1898), and Ruth McEnery Stuart in In Simpkinsville (1897)), yet they were much less likely to create the remote, outside narrative voice and often used dialect to achieve less patronizing, more flexible versions of life in community. As we will see below, some white writers and many African American writers during this period adapted local color trappings to literature which set itself against the conservative political agenda of traditional Local Colorists.

The Civil War Novel

Southern Civil War literature is distinctive primarily because of its tendency to deal not only, or even primarily, with the conditions of the 1861–1865 war but with the whole fabric of the society that preceded it. There are some valuable treatments of the war period by writers who actually were involved in events both at home and on the battlefield: John Esten Cooke's battlefield stories (1866), Sidney Lanier's Tiger-Lilies (1867), Augusta Jane Evans Wilson's Macaria, or The Altars of Sacrifice (1864), and Eugenia Jones Bacon's Lyddy: A Tale of the Old South (1898), are examples. The brilliant war-time diary of Mary Chesnut, A Diary from Dixie (1905), could also be included here. Yet the most enduring southern fiction produced to cover the historical scope of the Civil War is that of twentieth century writers whose works display some version of pastoral. Thus they incorporate, with varying degrees of both longing and irony, detailed visions of plantation life on the eve of the conflict. What is emphasized in the "before the War" sections of such works is the image of the South as a traditional society, securing individuals within sustaining constructions of family and community. "In my day," a young protagonist’s grandfather tells him in Allen Tate's novel The Fathers (1938), "we were never alone." If we consider Stephen Crane's Red Badge of Courage (1895) or Ambrose Bierce's Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1891) to offer an "American" model of the Civil War novel, then we see the terms through which we need to distinguish a southern genre, represented by Ellen Glasgow's Battle-Ground (1902), Mary Johnston's The Long Roll (1911) and its sequel, Cease Firing (1912), Andrew Lytle’s The Long Night (1936), Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind (1936), and Caroline Gordon's None Shall Look Back (1937), along with Tate's The Fathers and Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! (1936) and The Unvanquished (1938). Unlike Crane and Bierce, these writers, although differing in technique and artistic as well as political vision, nevertheless begin with the presumption that they must look back (as Gordon's title ironically warns against). For them the Civil War is not a cataclysm set apart from lives contained within community scrutiny, social obligation, and family interaction. The southern works listed above gather families into prescribed rituals as a kind of prerequisite to any dramatization of war. In other words, their conception of war places it within a set of social realities, not apart from them. These works also follow the pastoral in its double thematics: one track setting up the simpler life of antebellum plantation society as a more healthful, life-sustaining time and the other warning that memorializing the past distorts it, while enshrining the past overpowers the present. This reading of the threat implied in the pastoral is the theme of Allen Tate's poem "Ode to the Confederate Dead" (1928).

The most brilliant Civil War novel North or South is one that defies genre classifications but one that retains the southern groupings' emphasis on human relationships beyond as well as within war. Evelyn Scott created in The Wave (1929) an immense kaleidoscopic epic of lives thrown into chaos through the disorder of war. Its title image indicates the rising and breaking, overpowering force of unchecked emotions that her disconnected, character sketch structure also reflects. The narrative consists of over one hundred separate but interlocking vignettes recording the workings of individual consciousness, from actual generals and President Lincoln, down to anonymous foot soldiers, children, widows, deserters, and lovers. Two acclaimed recent examples resist geographical as well genre categorization. Set as they are in the western North Carolina mountains and the borderland of Missouri, respectively, Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain (1997) and Paulette Jiles's Enemy Women (2002), like Scott's The Wave, foreground human nature and lives rooted in elemental social contexts without grinding the pastoral theme of the past's tyranny over the present.

Southern Agrarianism

In 1956, Robert Penn Warren, speaking at a reunion of the Fugitive poets who had banded together at Vanderbilt University in the 1920s, said, "The Past is always a rebuke to the Present. . . It’s a better rebuke than any dream of the Future" (Quoted in Louis Rubin, Jr., "Introduction" to the Harper Torchbook reprint of I'll Take my Stand. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1958, xiii.). The Fugitives—Warren, John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, and Donald Davidson chief among them—became modern spokesmen for southern agrarianism not only in their poetry, but also in biography, fiction, and literary as well as social criticism. Their agrarianism, outlined definitively in their 1930 manifesto I’ll Take My Stand, had its roots in a myth of a traditional agricultural South—populated by self-sufficient, stoically religious, well-educated, non-materialistic gentry. Their agrarianism exalts Nature over the Machine, Contemplation over Competition, Rootedness over Progress. Yet as Warren's reunion comments indicate, the past envisioned can be a rebuke to the present, but is not an agenda for the future. Warren himself had broken with the Southern Agrarian movement's conservative racial politics by the 1950s, and today their image of the South is often attacked as the construction of a southern male elite promoting a segregationist ideal as a false "Golden Age."

From the beginning, literature written within the perspective of southern agrarianism exalted the genteel conception of the farmer and his connection to the land as the means of his enjoying the good life. As Thomas Jefferson put it in a 1787 letter to General Washington, "Agriculture is our wisest pursuit, because it will in the end contribute most to real wealth, good morals and happiness." John Taylor of Caroline in his Arator essays (1813) was the immediate inheritor of Jefferson's vision, which found a renewal during the Reconstruction-era in poems of Sidney Lanier, such as "Thar's More in the Man" and "Corn." The agrarianism of the Vanderbilt Fugitives found complex expression in their poetry beginning in the 1920s (Ransom's "Antique Harvesters" and Davidson's "The Tall Men") and in novels such as Tate's The Fathers (1939), Andrew Lytle's Wake for the Living (1975), Caroline Gordon's Aleck Maury, Sportsman (1934), and stories such as Robert Penn Warren's "Blackberry Winter." Agrarian thematics were important to a number of southern women novelists of the 1920s and 30s as well. Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground (1925), Elizabeth Madox Roberts's The Time of Man (1926), Julia Peterkin's novels of African American rural life in South Carolina (Scarlet Sister Mary, 1928), and the stories collected in Katherine Ann Porter's The Old Order (1958) express an often mystical sense of their characters' relationship to the earth—not the typical objectification of woman as earth but woman as a source of sustenance and energy. Later writers such as Robert Morgan and Fred Chappell, who have been influenced primarily by Robert Penn Warren in both their poetry and novels, reflect the agrarian concern for man’s dislocation from his roots in nature. Wendell Berry's essays over thirty years have become influential agrarian statements that are now seen as counter-arguments to current endorsements of a globalist philosophy.

Southern Modernism

Modernism as a literary category in the United States designates patterns of mind and style as well as a relationship to the historical period of the early 1900s through World War II. Modernist artistic expression reflects the historically marked pressures of the early twentieth century: the disintegration or serious compromise of many forms of authority (religious, governmental, gendered); the development of technologies and intellectual frameworks that changed thinking about time, space, physical being, and consciousness (feedback from the work of Darwin, Edison, Freud, the Wright Brothers etc.); the mass migrations to the cities and the development of the potential of new media such as film and advertising. In the South, a new generation of writers absorbed these shocks and set themselves the task of interpreting the ramifications for traditional assumptions about their place within a conservative, southern society. They understood the need for new literary techniques, new ways of using language and organizing narrative, in order to deal with new questions about how to render, even where to look for, reality. While African Americans and both African American and white women writers had different vantage points on the radical changes taking place in the South, many writers, regardless of race or gender, were inclined to combine pastoral thematics with modernist technical innovations. William Faulkner's novels of Yoknapatawpha give classic expression to the underlying pastoral emphasis of much of the southern writing that addressed modernist issues. Faulkner found innovative linguistic and structural ways to access the past in order to dramatize the modern southerner's loss of traditional avenues of knowledge and his search for viable forms of order. The pastoral invocation of the past involves the idea of time as enemy (time synonymous with the sterile mechanics of motion, with chronology as a tyrannical absolute of order, and with death). Faulkner wrote novels that dealt definitively with modern man's (and sometimes woman's) disconnection from nature and memory, with the loss of faith in God or tradition, and with alienation from any sustaining conception of community. His technical manipulations of voice and consciousness in novels such as The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), and Absalom, Absalom! (1936) serve to disrupt chronology and to revitalize the sometimes equally tyrannizing capacities of memory. Other white writers, particularly Robert Penn Warren in All the King's Men (1946), Eudora Welty in her many novels and short stories, Walker Percy in The Last Gentleman (1978), and James Agee in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), used similar modernist narrative techniques, particularly the brooding, interiorized first-person consciousness fragmented into multiple points of view and disruptions of chronological time. Jean Toomer's masterwork of the Harlem Renaissance, Cane (1923), also combines pastoral thematics with modernist experiments with point of view, as does Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). Neither of these African American writers in any way glosses over the racial oppression associated with the southern rural landscape, but both assert that a search for inheritance and sustenance within a southern past is essential to the attainment of full identity. Southern women of the early twentieth century, African American and white, might be expected to have had problems finding empowerment within the context of images of land and traditional order. Yet from Kate Chopin and Ellen Glasgow as transitional figures of great importance, to Hurston, Elizabeth Madox Roberts, Eudora Welty, Katherine Ann Porter, and Harriet Arnow, southern women writers have returned to, revised, and revitalized the meaning of women's relationship to the land and to tradition.

The South's Counter-Pastoral Literatures

(Southwestern Humor, Counter-Pastorals, the Southern "Problem" Novel, Southern Grotesque)

For much of the twentieth century, critical focus within southern literary study has emphasized constructions of white elite experience within one rigidly controlled and controlling domain: the world of the plantation owners and their modern class descendants who manipulated state houses and social registers through economic privilege. Their stories, both in triumph and in loss, were considered the story, and their canon, so designated through dozens of literary studies and anthologies, conveyed a white male conservative reading of what mattered in the South. Just as strong, however, is a southern tradition of counter-pastoral literature. These works are by place-identified writers who have nonetheless written with a sense of disfranchisement and a will to criticize, not by constructing idealized myths of a romantic or tragic past but by confronting falsely based narratives of dominance. Their counter-narratives present many souths, as places of experience, not privileged artifacts of memory.

As early as 1728, one of the South's most privileged storytellers, William Byrd, writing in The History of the Dividing Line (1841) of how he and his team surveyed the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina, identified a different kind of line, one that separates southern counter-pastoral writing from the more elitist agrarian and pastoral genres. As he mockingly described the non-slave and non-landholding North Carolinians below "the line," Byrd in his description of "Lubberland" opened a space for a long tradition of southern works that offer an unruly version the South's inhabitants and manners. Like the literatures of slavery, the South's counter-pastoral literatures revise the dividing lines for the reading of southern cultures.

The South's counter-pastoral literatures create characters who subvert privilege based on race, class, gender or pride of place. As we have seen, some southern writers harnessed the pastoral genre's focus on a traditional past in order to express fear of change or frustration with the complexities of the present. One important strain of counter-pastoral writing answered this longing by harnessing the genre's equal potential for irony to expose the blindness or self-serving motives of the master class. Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) stands as perhaps southern literature's most compelling work of counter-pastoral. Charles Chesnutt's works, particularly the stories collected in The Conjure Woman (1899), and some of the New Orleans writings of Kate Chopin, Grace King, and George W. Cable.

Southwestern humorists were pioneers of counter-pastoral literature who debunked notions of class privilege upon which much southern pastoral has been constructed. This rowdy genre gave Twain some of his most useful models for contesting the emerging white racist power structure of Post-Reconstruction. Using subversive trickster humor, the southwestern humorists of antebellum times displaced the traditional gentleman, supplanting him not with a counter-ideal but with rugged, sometimes openly anarchist anti-heroes.

Counter-pastoral realists of the twentieth century rejected myths of a "usable past" as they confronted urgent contemporary problems set within everyday dimensions of space and time. Their works present competing versions of the roots of southern culture that challenge the modernist tendency to privilege historical consciousness over social conscience. They wrote works not dominated by white traditions of authority, by “sense of place,” or by monolithic constructions of community. These southern literatures are not conceived as "acts of memory" involved in "recovering" the Past. Instead such works emphasize locating and questioning realities in the present, starting with the question of whose stories are actually being lived in heterogeneous souths, the souths acclaimed by C. Hugh Holman in his powerful revisionist essays, "No More Monoliths" and "The View from the Regency Hyatt."

When one finds the rich veins of literature that exist beyond the plantation South and beyond the experience of white privilege, the South becomes multi-dimensional in several respects. A variety of southern regions appear as important sites of economic and social organization. New kinds of characters are presented as positive figures: the African American school teacher, the redneck truck driver, the poor white single mother become subjects and voices instead of objects or hapless victims. The counter-pastoral novel zeroes in on the social change by portraying characters predominantly within plots of economic struggle. "Grit Lit" tells about the South with heavy doses of "gritty" violence, starkly rendered commonplace settings, and people whose lives are lived within frames of elemental struggle, not ornamental ritual.

In some even more estranged counter-narratives, writers' visions of multiple are produced from surreal distortions of traditional place and gentrified characters. The Gothic horrors of the southern-born Poe, the outrageous exaggerations of the antebellum southern humorists, the grotesque bodies of post-Renascence writers such as Flannery O'Connor, Carson McCullers, Lewis Nordan, and Randall Kenan take center stage in these assertions of myriad souths against the "chosen" South of one literary tradition.

Counter-Pastorals of Race and Class

Mark Twain's Huck Finn is southern literature's poster boy for counter-pastoral. He has no "truck" with what has been called "the party of the past." Given his precarious social position, he can only question the advantages of belonging to a world that thrives on tradition. His backward glance is taken through the eyes of a child who exists uneasily on the margins of a supposedly idyllic village. His ambivalence is traced satirically in his relations on the one hand with Jim, a slave, and on the other with several varieties of white communities. By the time that Twain wrote Pudd'nhead Wilson in 1894, even Huck's mild pastoral meditations, dreamy reflections made as he floats briefly out of time with Jim on the river, have been banished. Pudd'nhead Wilson confronts the absurd final consequences of white southern racist order.

Several other southern writers of the 1880s and 90s also wrote against the mythologizing currents of much "New South" writing in counter-pastoral fiction that utilized many of the staples (noted above) of local color. Charles Chesnutt's The Conjure Woman (1899), with its intricate frame narration, allows the black former slave narrator Uncle Julius to undercut all the nostalgic functions that the faithful retainer type performed for pastoral writers such as Joel Chandler Harris and Thomas Nelson Page. Uncle Julius, in rich vernacular dialect, critiques the white racist and class assumptions of the outside frame narrator, John. His conjure stories are set before the Civil War, but Chesnutt looks at the slavery era not to idealize the past, but to offer analogies between the brutal governance of slaveholders and the racist political assumptions and policies of the present, North and South. George Washington Cable in The Grandissimes (1880) more directly attacked racial prejudice through mulatto characters negotiating the complex color lines of New Orleans, a metropolitan region that offers an extreme version of caste, class, and race politics. Kate Chopin and Grace King also depicted mulatto characters who transgress the illogically racialized social structures of New Orleans, as did the African American writer Alice Dunbar-Nelson.

At the turn of the twentieth century African American writers James Weldon Johnson (in The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912)) and W.E.B. DuBois (in Souls of Black Folk (1903)), as well as Chesnutt (in The Marrow of Tradition (1899) especially), made the South a site synonymous with racial violence and injustice. A masterwork of twentieth century African American fiction, Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), can also be seen as counter-pastoral, especially in its construction of a very different mythology out of the oral folk culture of African Americans.

Southwestern Humor

The southwest as a regional literary imaginary has its boundary wherever the southern backwoods begins to meet the outer edges of civilization. The tales of this genre belong not to what we now know geographically as the Southwest (e.g. Arizona and New Mexico) but to the southern frontier, which might be western Mississippi, or any sparsely settled section of Alabama, Tennessee, or middle Georgia, wherever regulated society had not yet taken root. When Johnson Jones Hooper's con man protagonist Captain Simon Suggs comments (in Some Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs (1845)) that it is "good to be shifty in a new country," he identifies the imaginative landscape of southwestern humor. It is the "new" place that gives the lie to the ideal of the "Old" South as place distinguished by tradition, history, manners, and law. The nineteenth century humorists were usually men of education and urbanity writing for popular men's magazines. In their unruly representations, a man can lose his nose in a fight (in Augustus Baldwin Longstreet's Georgia Scenes (1835)); transplanted Virginians trying to "lord" over others in frontier communities are routinely victimized by sharper drifters with no pedigrees (in Joseph Glover Baldwin's Flush Times in Alabama and Missisippi (1853)); a phony preacher can be conned by an even phonier convert (in Hooper's Captain Simon Suggs); a lowlife of the first order named Sut Lovingood can victimize innocent bystanders simply because he is feeling out of sorts (in George Washington Harris's Sut Lovingood Yarns (1867)).

The southwestern humor tales satirize many elements of antebellum plantation fiction through tricksters who in their disdain for the classic virtues hold up an ironic, inverted mirror to slave-holding society and its hypocrisies. The stories contain exaggeration of both speech and incident, while their protagonists both critique and subvert the dominant power structure. At their most violent or absurd, the tales of the genre offer versions of anarchy that seem especially to target preoccupations with social class. The poor white challenges any class claim to superiority. In the world of hunting, horse-swap, yarn-spinning, and woman-bashing that marks the genre, the condescension of the gentleman or dandy is no match for the resentment and the amorality of an unaccommodated breed of backwoodsman.

Although southwestern humor tales have long been considered a male genre, in part because of their popularity in men's sporting journals, southern women also took to this form, generally somewhat later and within the generic conventions of local color. Idora McClellan Plowman Moore, recently given new attention by scholar Kathryn McKee, wrote comic sketches for southern newspapers (1881–1900) that clearly belong to the southwestern humor tradition, especially in her use of poor white storyteller Betsy Hamilton. (Dissertation: Writing in a Different Direction: Postbellum Women Authors and the Tradition of Southwestern Humor, 1875–1920).

Southern "Problem" Literature

When the South was identified by President Franklin Roosevelt as America's "number one" economic problem in the 1930s, southern writers were already responding to the realities of the rural and industrial poor with fiction that has often been included in categories of "Social Realism," "The Protest Novel," or the "Proletarian Novel." Very seldom has this literature been included in studies of "southern renascence" literature. In Rubin's Southern Renascence, which staked out this territory in 1952, Erskine Caldwell was the only modern writer included who is not identified with the agrarian or pastoral/modernist orientation. Recently Richard Gray (in Southern Aberrations (2000)), labeled one of his groupings "Stories of the Rural Poor between the Wars." Giving the title Southern "Problem" Literature to a set of southern writers draws upon the South's dubious distinction, during the 1930s, as the section of the United States identified as "worst off" in terms of all economic indicators, but it also reflects other denominators affecting life in the modern South: problems related to racism and white supremacist politics, to the ideological over-valuing of a rural gentry which contributed to anti-labor policies and "redneck" stereotyping, and to the rigid class structure that made social mobility especially difficult for poor southerners, white and black. A genre of "problem" literature incorporates these factors into its dramatic treatment of poverty and injustice. Writers in this group stake out resistance specifically to agrarian and pastoral literatures that gloss over racism and the suffering of sharecropping farm families in their attempt to associate the good life with idealizations of the past or life lived close to nature.

T.S. Stribling was an early pioneer of southern problem literature who belonged to what was known as the "revolt from the village" school associated more with northern and midwestern writers such as Sinclair Lewis. Erskine Caldwell was probably the most visible but also most controversial of the "problem" novelists in the 1930s, scoring with sensationalist, grotesque portrayals of poor whites (in fiction such as Tobacco Road (1932)) but also with a more realistic, sympathetic photo-documentary text (with Margaret Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)). Very different from the outside observer Caldwell was Harry Kroll, who in a non-fiction account, I Was a Share-Cropper (1937), and in novels such as The Cabin in the Cotton (1931) approached poor white tenant farming from his own experience. Richard Wright (in Uncle Tom's Children (1938) and Black Boy (1945)) also experienced firsthand some of what he shows in this collection of short stories: the doubly brutalizing existence that poor blacks endured in the rural South.

Probably the earliest novel to focus on poor whites was Edith Summers Kelley's Weeds (1923), a naturalistic study of Kentucky tobacco farming. Her position points to an interesting aspect of southern problem literature, the relatively high number of women writers who turned to its resistance format. Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind (1936) was a brilliant version of the modern historical romance form that many women, nation-wide, were successfully mastering. Still, many southern women writers moved away from this traditional women's market. Lillian Smith (in her novel Strange Fruit (1944) and her eloquent, confessional autobiography Killers of the Dream (1949)) took a courageous stand against segregation. Resistance autobiographies like Smith's that concentrate on the "problem" of class and race discrimination have been a special province of southern women writers. They represent experiences that cross these divisions, from Katherine Du Pre Lumpkin's The Making of a Southerner (1947), charting a white woman's growing distance from an upper-class family's paternalistic racism, to Anne Moody's Coming of Age in Mississippi (1968), describing a black girl's adolescence in an impoverished rural household, and from Ellen Douglas's Truth: Four Stories I am Finally Old Enough to Tell (1998), concerning her middle class family's racist past, to Linda Flowers's firsthand account, in Throwed Away (1990), of growing up in a sharecropping family. Southern women writers were also frontrunners in treating the urban, industrial South in the 1930s. In 1932 three southern women, Olive Tilford Dargan, Grace Lumpkin, and Myra Page, published novels about the 1929 textile millworkers strikes in Gastonia, North Carolina. Harriette Arnow's The Dollmaker (1954) brought an Appalachian woman writer's viewpoint to the issue of the effects of industrialization on rural families through her story of a displaced Kentucky family during World War II. In 1960 another southern woman writer, Harper Lee, published what is probably the modern South's most popular novel of social protest, To Kill a Mockingbird.

Southern Grotesque

Contemporary writers such as Harry Crews (in A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978)) and Dorothy Allison (in Bastard Out of Carolina (1992)) deal with the experience of poor whites in graphic ways that in some respects makes them southern problem naturalists, but in others allies them with the genre of the Southern Grotesque. Often the terms Gothic and Grotesque are interchanged when applied to the South (the only place to which both rubrics have been consistently applied as literary denominators). "Southern Gothic" and "Southern Grotesque" refer to literature that mixes terror and horror in order to shock or disturb. Writers of southern Gothic or Grotesque combine comic or obscene exaggeration with sometimes gratuitous violence, often within representations of physical deformity or sexual deviance. The Grotesque genre in southern literature begins with southern-born Edgar Allan Poe, whose radical experience of repression and alienation (in his case, alienation from the upperclass Richmond society of his adoptive father) is reflected in the nightmare landscapes that appear in his fiction. His gothic works of horror appeared around the same time as southwestern humor writing, and as different as the two genres might seem, they share elements of distortion and displacement, gratuitous violence, and outrageous hostility. Possibly these similar traits represent a kindred response to the stultifying effects of traditional antebellum plantation society, which in a resistance view functioned only through blindness to the horrors inherent in slavery and through pretentious rituals of honor and obedience. In stories such as "The Masque of the Red Death" and "The Fall of the House of Usher," Poe presents terrifying, irrational inversions of order. His characters' obsession with control explodes into bizarre excesses and disfiguring disease.

Faulkner, Eudora Welty, and Tennessee Williams apply different kinds of gothic effects in some of their works, often as they address alienation and disorder in modern southern settings. Yet the most interesting, and most radical inheritors of the Grotesque are women writers of the later modernist era, Carson McCullers and Flannery O'Connor, who developed this sensibility into very different strands. McCullers in The Ballad of the Sad Café and O'Connor in stories such as "Good Country People," "The Life You Save May Be Your Own," and "Revelation" displace the horrors of a world without morality or reason onto grotesque female bodies. Their deformed, freakish, psychotic, or imbecilic female characters are inversions of the pure white southern woman, icon of the well-ordered universe of southern tradition. The dramas of Tennessee Williams and the stories of Truman Capote and Peter Taylor reflect this iconography of estrangement as well in physical, often sexual grotesqueries. If the South seems especially hospitable to such types, some scholars and writers speculate, it may be because its social codes have allowed so few avenues for the expression of disagreement or even confusion about the controlling norms.

Flannery O'Connor's affinity for the grotesque is unique because her explanations and usages are tied to her firm sense of spiritual realities that southerners, she says, have always been more ready to acknowledge than other Americans. Her imagined South is defined as that "Christ-haunted landscape" in which characters can be forgiven anything except spiritual complacency. Epiphanies occur for O'Connor's ideal modern readers when they experience a sense of the uncanny (translated for O'Connor into spiritual grace) through the grotesque mode's combining of strange, often violent "discrepancies" or oppositions in plot, character or imagery.

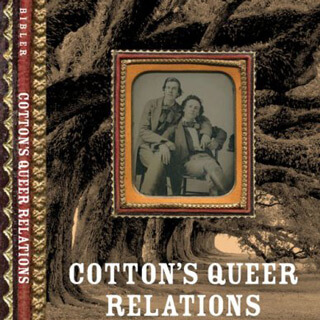

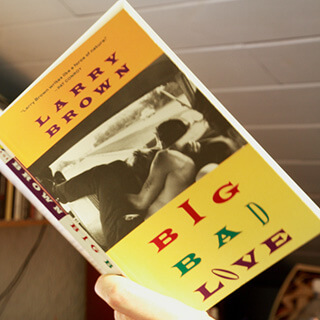

Following O'Connor, and deeply indebted to her, are several contemporary southern writers who are interested in her use of the Grotesque as a way to critique a stultifying, spiritually arid modern landscape. Cormac McCarthy, Harry Crews, Barry Hannah, Tim McLaurin, Lewis Nordan (especially in Wolf Whistle (1993)) and Larry Brown apply the principles of the Grotesque in works of fiction that often are considered under a separate rubric, that of "Grit Lit" (not to be confused with the use of the term "Gritlit" for all of southern literature). Like O'Connor's grotesque comedies, some of these writers' works can be violently comic, while others are more likely to shock or repulse readers through raw portrayals of life at its grimmest. Grit Lit can chart the disintegration of characters bereft of dignity or hope but it can also call forth sympathy for forgotten lives and wasted promise. Larry Brown's Fay: A Novel (2000) and Cormac McCarthy's Suttree (1979) are two prime examples.

About the Author

Dr. Lucinda MacKethan recently retired as Alumni Distinguished Professor of English at NC State University, where she taught courses primarily in Southern and African American literature. She is the author or editor of six books, including Daughters of Time: Creating Women’s Voice in Southern Story and the co-edited Companion to Southern Literature, named a “Best Reference Work” by the American Library Association. Dr. MacKethan was a fellow at the National Humanities Center and chaired the North Carolina Humanities Council from 2002 to 2005. She writes curricula and leads seminars for the National Humanities Center’s online high school teacher enrichment programs and was senior consultant for the NEH award winning website Scribbling Women. She also lectures locally and nationally on the culture of the Old South.

Publication History and Update

In winter 2016, Southern Spaces updated this publication as part of the journal's redesign and migration to Drupal 7. Updates include a full collection of new images and text links, as well as revised recommended resources and related publications. For access to the original layout, paste this publication's url into the Internet Archive: Wayback Machine and view any version of the piece that predates January 2016.

Recommended Resources

Text

Andrews, William L. To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760–1865. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986.

Beebee, Thomas O. The Ideology of Genre: A Comparative Study of Generic Instability. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

Brinkmeyer, Robert H. Remapping Southern Literature: Contemporary Southern Writers and the West. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000.