Overview

Robert Macfarlane's Is a River Alive? draws upon interviews with Rights of Nature advocates who are countering the consequences wrought by extractive industry and climate change on major river systems. Macfarlane evokes wonder for the natural world, while identifying the threats nature faces in the Anthropocene era.

On its face, British author Robert Macfarlane’s most recent book Is a River Alive? (2025) has very little to do with customary Southern Spaces locales. Starting from his home base in the south of England, Macfarlane travels to riverscapes that range far afield—a cloud forest stream in Ecuador, polluted watercourses in southeastern India, and a string of lakes and rivers in eastern Canada. But his revolutionary argument, that rivers are indeed alive, despite all that humans have done to try to kill them, finds resonance in the US South, with its many endangered riverine habitats.

Is a River Alive? follows on Macfarlane’s 2019 bestseller, Underland: A Deep Time Journey, which explores underground worlds as different as the Paris catacombs, Greenland’s glacial moulins or crevasses, and the “starless” or subterranean rivers along the Italy-Slovenia border.[1] The new book evokes similar wonder for the natural world, while even more pointedly identifying the threats nature faces in the Anthropocene era.

In Is a River Alive? Macfarlane investigates Rights of Nature (RoN) movements, interviewing local advocates who are countering the consequences wrought by extractive industry and climate change on major river systems. The Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature defines the concept: “Nature in all its life forms has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycle.”[2] Inspired in part by the landmark 1972 essay by philosopher Christopher D. Stone, “Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” RoN advocates seek to vest nature with legally enforceable rights.[3] Rivers, Macfarlane argues, occupy a central place in this movement.[4]

To make his case, Macfarlane takes the reader on river journeys to three places under particular threat, traveling first to Ecuador’s Los Cedros cloud forest. Among Macfarlane’s companions along the Río Los Cedros are attorney César Rodríguez-Garavito, a Colombian social justice advocate, and musician Cosmo Sheldrake. Also joining is Italian-Chilean mycologist/filmmaker Giuliana Furci, whose astonishing discoveries of rare and unknown mushrooms along the route delight those on the journey, making scientific history and underscoring the need for protecting the region.[5]

The Los Cedros explorers also include two jurists—Ramiro Ávila Santamaría and Agustín Grijalva Jiménez—who were instrumental in advancing the Rights of Nature movement in Ecuador. The group meets up with Josef DeCoux, who spent most of his life advocating for the forest, living at the remote Los Cedros Scientific Station, which he founded after moving to the region in the 1980s. DeCoux, who died in 2024, brought the successful rights of nature lawsuit against multinational gold and copper mining companies based on the Ecuadorean constitution, which in 2008 recognized the rights of nature in that country.

The second journey explores the polluted waters in Chennai, a major city on India’s eastern coast, along the Bay of Bengal. As Macfarlane traces one of the rivers that lead into Chennai from its inland headwaters, he is reminded of the iconic maps drawn in the early 1940s by geologist and cartographer Harold Fisk of the wanderings of the Lower Mississippi, tracking the floodplain’s “former lives.” So, too, in Chennai, geophysical phenomena, cyclones and typhoons, and extractive mining and trading practices dating back four centuries to the Dutch East India Company reshaped the watery terrain.[6]

During his third journey, Macfarlane faces a treacherous-in-places kayak trip on the Mutehekau Shipu river that feeds into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in eastern Canada. At one point, the kayakers face raging wind and waves and swirling waters. “We are drawn irrevocably into the rapid, like space-debris caught in a black hole’s pull,” Macfarlane writes. The river’s rights in this region near the border of Quebec and Labrador are advanced by the Mutehekau Shipu Alliance. The Alliance is composed of members of the Indigenous Innu Council of Ekuanitshit, many of them women, along with hikers and kayakers, municipal leaders, and conservationists. The Alliance has worked to win recognition of the river as a “rights-bearing entity” and to prevent additional dam-building along the river’s course.[7]

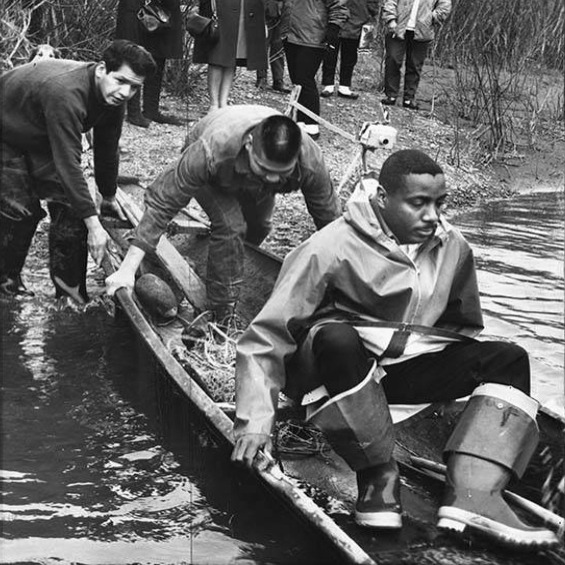

Throughout these journeys, Macfarlane draws on a long tradition in “Indigenous cosmo-visions” to argue that human survival is fully entwined with the rights of nature.[8] And, indeed, it is Indigenous leadership that has propelled forward Rights of Nature campaigns around the world.[9] Ecuador’s fourteen Indigenous nations pressed the 2008 Constitutional Assembly for recognition of nature’s rights.[10] The Sarayaku people—long subject to militarized oil company incursions and explosive seismic prospecting—have stood up for “Kawsak Sacha,” “The Living Forest,” pushing Ecuador to live up to its innovative constitution, publishing a declaration of forest rights in 2012. Mi’kmaq leaders in Canada have identified as ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’ the blending of Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge and Western ways of knowing through scientific botany. [11]

The rights of nature concept can also be traced to nineteenth century European nature adventurer Alexander von Humboldt. Macfarlane notes that Humboldt saw “the natural world as an interconnected web of life, in which nothing existed in isolation and humanity was not the central actor, merely a node among many in an immense, rhizomatic network.”[12]

Though he casts a river not as “what” but as “who,” Macfarlane aims to avoid direct personification of the natural world. Rivers do not have rights in the same ways humans have rights, he acknowledges. “[T]o say a river is alive is not an anthropomorphic claim,” he writes, but it can “deepen and widen the category of ‘life.’” It is not uncommon, he notes, to speak of a river as “dying.” In Chennai, for example, despite a long history of “water-husbandry and water reverence,” several major waterways are lacking in dissolved oxygen, considered “dead.”[13]

Macfarlane quotes the US-born, Australia-based multi-species ethnographer Deborah Bird Rose, who wrote that, in the Anthropocene, nature experiences a “double death,” in which “the rapid extinction of life in the present leads also to the foreclosure of its future possibilities.”[14] This form of path dependency, in which current choices regarding nature constrain future options, is profoundly experienced in the waterways of the US South.

Many southern rivers have topped the endangered list in the past ten years. Coal ash dumping and agricultural pollution landed the Alabama River in two of the top five slots in American Rivers’ endangered list in 2022. In 2024, four of the nation’s most endangered rivers flowed through the South.[15] And, in 2025, six of the top ten of the nation’s most endangered rivers flowed through southern states.[16] A network of riverkeepers is working to reverse the degradation of these waterways. As UCLA law professor James Salzman has pointed out, “rights of nature” is a strategy as much a movement, a strategy that can promote democracy through local involvement.[17]

In this era of increasing assaults on the democratic rights of humans, expanding the rights of nature hardly seems probable in the US. Nature writer Elizabeth Kolbert described the RoN movement in The New Yorker in 2022, as, depending on one’s vantage point, “either borderline delusional or way overdue.”[18] Yet there are some promising examples on the local level, Kolbert notes, including some in southern states. In Seminole Territory in Orange County, Florida, rights of nature arguments have been deployed to protect Lake Mary Jane southeast of Orlando. And, in a further example of contemporary Indigenous leadership in the RoN movement, in 2022 the Rappahannock tribe in Virginia re-acquired ancestral lands in the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge, regaining control over 465 acres of land along the scenic river.[19]

At least eighty locales in the US have passed rights of nature laws or regulations. Yet, many of those laws have faced court challenges and have been rejected on the basis of “due process, vagueness and other grounds.” In one US case, the attorney who sought legal personhood for the Colorado River was even threatened with sanctions for filing a lawsuit.[20]

The journey from unimaginable to possible seems daunting. Even if the premise of RoN legislation—that nature has enforceable rights—began to find acceptance in the courts, many complications exist in finding appropriate remedies. One such problem, Macfarlane notes, is “shifting baseline syndrome,” as “each new generation measures loss against an already degraded benchmark.”[21]

The tone of Is a River Alive? is nevertheless hopeful. Cosmo Sheldrake, the musician who traveled with Macfarlane on the Los Cedros trip, recorded sounds of the forest the group encountered along the trip, noting the importance not only of humans listening to the forest, but also to ‘hear the forest listening.’[22] With sound recordings made along the journey, Sheldrake has created “Song of the Cedars.” He is petitioning to have the cloud forest recognized as a co-composer and author.[23]

Is a River Alive? is an engaging book that reveals anew the geophysical world, recounted with obvious emotion. Some readers might wish for an even sharper critique of the forces assailing rivers and the lands and human populations along their banks. Macfarlane’s aim—for readers to think more deeply about protecting waterways—stimulates such a critique. A helpful glossary and bibliography round out the book’s value as a spur to activism, a call to which the author himself is responding.

Macfarlane has continued his advocacy for the Rights of Nature campaign to protect Los Cedros, speaking out with César Rodríguez-Garavito in an opinion piece in The New York Times in summer 2025.[24] “It’s vital that the international community help Ecuadoreans resist this drastic rollback of environmental protections and assault on constitutional integrity,” they wrote. In this time of attacks on national sovereignty in that region of South America, their appeal serves as an even more critical call to heed.

About the Author

Ellen Griffith Spears is professor emerita of American Studies at the University of Alabama. She is author of Baptized in PCBs: Race, Pollution, and Justice in an All-American Town (UNC Press) and Rethinking the American Environmental Movement post-1945 (Routledge).

Banner image: Coosa riverscape photo copyright A. Odrezin. Used by permission of Coosa Riverkeeper, 2026.

[1] Robert Macfarlane, Underland: A Deep Time Journey (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019).

[2] Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, https://www.garn.org/rights-of-nature/, accessed December 11, 2025.

[3] Christopher D. Stone, “Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” Southern California Law Review 45, no. 2 (1972): 450-501.

[4] Robert Macfarlane, Is a River Alive? (New York; London: W.W. Norton, 2025), 29.

[5] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 85.

[6] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 158.

[7] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 257, 215.

[8] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 100.

[9] James Salzman, “Six Things to Know about the Rights of Nature,” Legal Planet, December 3, 2024, https://legal-planet.org/2024/12/03/six-things-to-know-about-rights-of-nature/.

[10] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 45.

[11] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 215.

[12] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 100.

[13] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 82, 22, 128, 127, 123.

[14] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 91.

[15] The Big Sunflower and the Yazoo, in Mississippi, are endangered due to the Yazoo Backwater Pumps, which despite their name offer limited protection against flooding; the Duck River in Tennessee, where overconsumption of water results from population and industry growth; the Little Pee Dee River in North and South Carolina suffers as a consequence of the construction of I-73 as does the Blackwater River in West Virginia, also due to major four-lane highway construction. American Rivers, America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2024, https://www.americanrivers.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/v8_AR_2024-Most-Endangered-Rivers-FINAL.pdf, accessed December 8, 2025.

[16] The endangered southern watersheds in 2025 are: the Mississippi River; the rivers of Southern Appalachia, including the French Broad, damaged by scour from Helene; the Lower Rio Grande in Texas; the Rappahannock in Virginia; the Gauley River in West Virginia; and the Calcasieu in Louisiana. American Rivers, America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2025, https://mostendangeredrivers.org/, accessed December 8, 2025.

[17] James Salzman, “Six Things to Know about the Rights of Nature.”

[18] Elizabeth Kolbert, “A Lake in Florida Suing to Protect Itself,” The New Yorker, April 11, 2022.

[19] “Secretary Haaland Celebrates Rappahannock Tribe’s Reacquisition of Ancestral Homelands, Press Release, April 1, 2022. https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-haaland-celebrates-rappahannock-tribes-reacquisition-ancestral-homelands (accessed April 15, 2025); Sarah Kuta, “Ancestral Homeland Returned to Rappahannock Tribe After More Than 350 Years,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 5, 2022.

[20] James Salzman, “Six Things to Know about the Rights of Nature.”

[21] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 23.

[22] Macfarlane, Is a River Alive?, 48.

[23] Samuel Firman, “Good Living,” Distillations Magazine, Science History Institute, December 4, 2025, https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/good-living/.

[24] César Rodríguez-Garavito and Robert Macfarlane, “The Most Environmentally Imaginative Country on Earth Is Under Assault,” The New York Times, August 15, 2025.

Cover Image Attribution:

Coosa riverscape photo copyright A. Odrezin. Used by permission of Coosa Riverkeeper, 2026.Recommended Resources

Text

Hoover, Elizabeth. The River Is in Us: Fighting Toxics in a Mohawk Community. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Kelman, Ari. A River and Its City: The Nature of Landscape in New Orleans. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York: Henry Holt, 2014.

McPhee, John A. The Control of Nature. 1st ed. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1989.

Morris, Christopher. The Big Muddy: An Environmental History of the Mississippi and Its Peoples, from Hernando De Soto to Hurricane Katrina. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Peach, Steven. Rivers of Power: Creek Political Culture in the Native South, 1750-1815. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2024.

Scott, James C. In Praise of Floods: The Untamed River and the Life It Brings. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2025.

Stradling, David, and Richard Stradling. Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Wulf, Andrea. The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humbolt's New World. New York: Vintage, 2016.

Worster, Donald. Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West. New York: Pantheon Books, 1985.

Web

Coosa Riverkeeper. The Voice of the Coosa River. Pitts Media, 2025.

Lorentz, Pare, and United States. Farm Security Administration. The River: A U.S. Documentary Film. Washington: 1937. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007640253/

The Los Cedros Scientific Station. Estación Científico Los Cedros. https://reservaloscedros.org/