Overview

Robert Gioielli reviews Ellen Griffith Spears's Rethinking the American Environmental Movement post-1945 (New York: Routledge, 2019).

Review

For more than twenty years, scholars have sought in article after book after conference paper to expand the timeline, reach, and definition of environmental concern and activism. This uncoordinated but multi-pronged effort has given us a fuller sense of activism that emerges from and addresses larger social and economic inequalities. What we call environmental justice is finally getting a full and complete history.

What has yet to be done, until now, is to bring that broader story together with the more traditional history of the environmental movement. Ellen Griffith Spears has accomplished that in her important new history, Rethinking the American Environmental Movement post-1945. In this tightly argued volume, Spears provides the first work that truly synthesizes the different strands of environmentalism, giving them equal narrative and analytical weight. This book represents the culmination of a generation of scholarship on environmentalism that sought to expand our narrative in order to consider environmentalism as a "field of movements" (5) that brings together actors, organizations and institutions from a variety of backgrounds at the local, regional, and national level. The field of movements concept allows Spears to consider the mainstream organizations such as the Sierra Club or the Natural Resources Defense Council on comparable footing with grassroots movements, working to weave all strands of activism into the synthesis. She also includes developments in the history of science and public health, especially in ecology and toxicology, as well as the regulatory responses by the federal government. These are important not only to provide background and context, but also because the often-contested terrain of scientific knowledge and expertise is so central to understanding the movement. Rethinking the American Environmental Movement also engages larger structural changes within the US economy and society, such as mass suburbanization in the 1950s and deindustrialization in the 1970s and 1980s.

Although the title of the book promises an emphasis on the post-World War II era, the first chapter is a robust examination of "Antecedents" to the modern movement. Where, for instance, traditional histories examined conservationism and perhaps Progressive Era smokestack regulation, Spears discusses resistance to slavery, and pre-Civil War public health debates, in addition to the emergence of nature preservation. This builds on important recent work in nineteenth-century environmental history, such as Catherine McNeur's Taming Manhattan and Carl Zimring's Clean and White, and buttresses the argument for long durée connections between social justice and the environment.1Catherine McNeur, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City, Reprint edition (Harvard University Press, 2017); Carl A. Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2015); Mark Fiege, The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012).

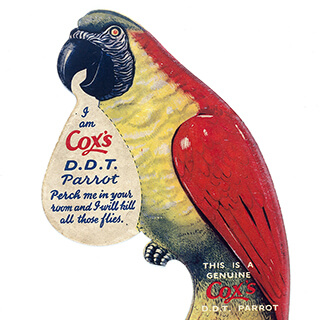

The core of Spears's book centers on the postwar period, which she ably covers while also introducing lesser known developments. For example, any book of this nature has to discuss Rachel Carson, and Rethinking devotes one of its largest section to this groundbreaking author. But instead of putting Carson on a pedestal, where she often sits in public memory, Spears places her in context, showing how she was building on and amplifying the work of grassroots activists and scientists. Americans had been raising concerns about the ecological and public health effects of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) soon after World War II. This accelerated into a series of lawsuits filed by New York based conservationists protesting the indiscriminate spraying of DDT in the late 1950s. The legal action failed, but the activists caught the attention of Carson, who began investigating the impact of DDT across the country. That research culminated in the publication of Silent Spring in 1962, and Spears ably delineates how and why this book was so important. It was not just an expose about the dangers of chemical spraying; Carson helped bridge the old conservation era to more contemporary concerns about human health, and she "crystallized the recognition that humans were fundamentally altering the environment" (83).

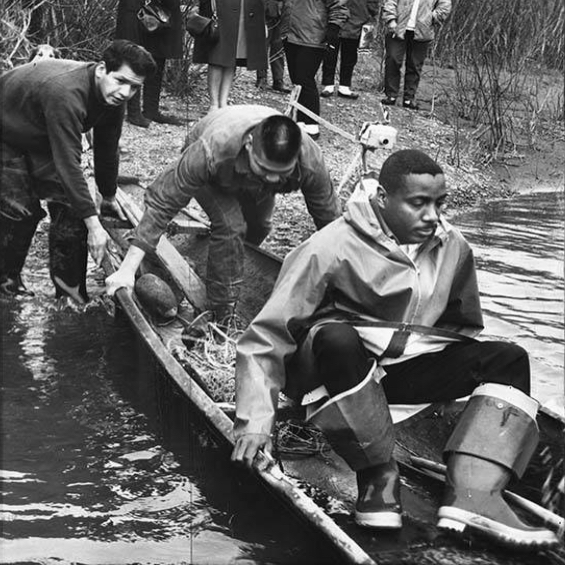

Just as significant as this rethinking of Silent Spring and pesticide activism is what comes before it: a short but important consideration of urban environmental concerns during the 1950s—especially the National Urban League's "fight blight" and block club campaigns that targeted neighborhood cleanup, rats, empty lots, and community health. Spears examines urban activism by African American and other minority populations in more detail later, but by putting this section right before the discussion of Carson, she makes a valuable narrative intervention. Justice-focused activism by minority communities was occurring at the same time that more well-known parts of the movement were emerging, buttressing the argument that these strands of environmentalism are deserving of a longer history, and were not just a product of the environmental justice movement of the 1980s.

In addition to making sure that urban and minority neighborhoods and populations are firmly part of the narrative, Spears gives significant weight to the decades after 1980. This allows her to cover the conservative reaction to environmentalism during the Reagan administration and afterwards, but also climate activism, and recent environmental justice conflicts such as poisoned water in Flint, Michigan, and the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. Rethinking is especially strong on climate activism, representing an important shift over the past decade. The final chapter provides background on concerns over anthropogenic climate change (a subject that has figured in every United Nations environmental since 1972) and the international negotiations and treaties over the limitations of carbon and greenhouse gases in the 1990s. Spears includes a special section on the Dakota Access Pipeline protests in 2016. Because the pipeline violated indigenous rights, was a threat to the water supply of the Standing Rock Reservation, and would also allow for the cheaper transportation of fossil fuels, Spears argues that the NO DAPL protests were a great example of "an intersectional grassroots movement linking indigenous rights, climate change, and water protection" (213).

By the end of the Rethinking, readers may feel a little overwhelmed by the field of movements approach, as Spears jumps, for example, from climate activism, to green jobs, food justice, religious work on climate change, and to standalone discussions of Flint and Standing Rock, all in the second half of the last chapter. Critics could argue that this "big-tent" conceptualization risks diluting what they would classify as an environmental movement, but this is the value of Spears's approach. She convincingly shows how environmentalism has never been one particular set of activists or institutions, but a diverse set of organizations, scientists, firebrands and regulatory bodies that have always been in conversation, conflict or coalition with each other. This broad coverage helps readers understand many implicit and explicit connections. And coverage is one of the goals of this kind of book, which seeks to introduce a topic to a broader audience. This makes Rethinking especially admirable. It places activism centered upon injustice and inequality on equal footing with more commonly known parts of the movement. As someone who teaches the history of environmentalism, I believe this is vitally important. Most students begin with strong preconceived notions about environmentalism (Birkenstocks, tofu) that prove tough to dislodge.

This field-of-movements framework does raise a broader question within environmentalist writing and the narrative we tend to tell. Lurking beneath the surface of many histories of environmentalism is the conflict between the movement's different strands, particularly between environmental justice organizations, radical wilderness groups, and the mainstream "nationals." Spears does not shy away from these tensions, showing how radical factions emerged partly in opposition to the perceived "business friendly" policies of groups such as the Environmental Defense Fund, and how grassroots organizations have long been critical of the overwhelming white, middle-class staffing and policy orientation of well-funded national groups based in Washington, DC.

Rethinking lacks an exploration of the roots of these tensions. This is primarily because of the strictures on the length of such a synthetic book—and that there are not yet enough strong critical histories of the mainstream strands of environmentalism. The discussions of the close relationship between corporations and large national groups are a case in point. Spears draws on the work of journalist Mark Dowie, especially his groundbreaking 1995 book, Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century. Dowie was one of the first vocal critics of this relationship, but this book is now a quarter-century old, and there really hasn't been any work that goes beyond his primarily surface level, muckraking analysis.2Mark Dowie, Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1996).

We need more work that takes the connections between corporations and major, national environmental groups at face value, and attempts to understand their roots and trajectories—and their lack of attention to people and geographies of color. One of Spears's primary concerns is the "multiple ways in which the color lines drawn in U.S. society have hampered environmental reform movements" (4). But as strong as it is in exploring the grassroots activism by people of color, Rethinking doesn't explore the color lines that existed in environmental organizations; why they were reluctant, for decades, to address the concerns of marginalized groups, or even make their professional staffs more diverse. This is not because Spears does not want to explore these problems. It's simply that the literature is not there. The white privilege of US environmentalism has only really been critiqued at the margins. We lack a full accounting of its development and impact, particularly on the continual escalation of environmental injustice and inequality.

What are the reasons for these deficiencies, at least within US environmental history? The most obvious arguments would be that the field, or at least the powerful and influential within the field, were for decades overwhelmingly white, male, and middle class, and had a vested interest in a set of narratives about American environmental reform. Perhaps more importantly, there was also a reluctance to attack or even critique these narratives. Not only did generations of scholars have so much invested in these heroes, but also because to many of us, environmentalism has maintained a certain moral certitude as a progressive politics.3The core "heroes" come from the wilderness and early conservation movements. See, for example, Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale University, 1996 [1965]); Aldo Leopold A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There (London: Oxford University Press, 1949). To tar it with racism, and corporate greed, especially in a post-Civil Rights, neoliberal America, could undermine the whole project.

Finally, scholars are beginning to get over that reluctance. New work by Jennifer Thomson, Paul Sabin and Keith Woodhouse, for example, digs into environmentalism to understand its flaws, contradictions and their ramifications.4Paul Sabin, "Environmental Law and the End of the New Deal Order," Law and History Review 33, no. 4 (November 2015): 965–1003; Jennifer Thomson, The Wild and the Toxic: American Environmentalism and the Politics of Health. (University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Keith Makoto Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists: A History of Radical Environmentalism. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). They move beyond a celebratory narrative to embed the environmental movement within the larger political and social developments of the past half-century. Outside the discipline of history, scholars such as David Pellow, Lisa Sun-Hee Park, and Dorceta Taylor have cast critical judgment on the movement, especially when understanding race in environmental politics.5Lisa Sun-Hee Park and David N. Pellow, The Slums of Aspen: Immigrants vs. the Environment in America's Eden, (New York: New York University Press, 2011); Dorceta E. Taylor, The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection (Durham, NC: Duke University Books, 2016). All of this work is important, but we need more.

Telling a more critical, less rosy story is important because a strong, inclusive and self-reflective, environmental movement is more important now than ever. Writing movement history is always political, especially when the social movements remain ongoing and their success more urgent. With Rethinking the American Environmental Movement post-1945, Ellen Spears has done admirable work in expanding our conception and understanding of the movement's varied streams.

About the Author

Robert Gioielli is an associate professor of History at the University of Cincinnati and the author of Environmental Activism and the Urban Crisis: Baltimore, St. Louis, Chicago (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014). Find him on Twitter at @robgioielli.

Recommended Resources

Text

Bullard, Robert D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1990.

Dowie, Mark. Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996.

Gottlieb, Robert. Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005.

Park, Lisa Sun-Hee, and David N. Pellow. The Slums of Aspen: Immigrants vs. the Environment in America's Eden. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

Powell, Miles. Vanishing America: Species Extinction, Racial Peril, and the Origins of Conservation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Sabin, Paul. "Environmental Law and the End of the New Deal Order." Law and History Review 33, no. 4 (2015): 965–1003.

Spears, Ellen Griffith. Baptized in PCBs: Race, Pollution, and Justice in an All-American Town. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Taylor, Dorceta E. The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Thomson, Jennifer. Wild and the Toxic: American Environmentalism and the Politics of Health. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Wells, Christopher. Environmental Justice in Postwar America: A Documentary Reader. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

Woodhouse, Keith Makoto. The Ecocentrists: A History of Radical Environmentalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.

Web

Bailey, Louis D. "Louis D. Bailey." Interview by Louise Sunshine. A People's History of Harlem: A Harlem Neighborhood Oral History Project. New York Public Library (New York, New York). April 26, 2014. oralhistory.nypl.org/interviews/louis-d-bailey-2cdd67.

"Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement." Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison (Madison, Wisconsin). Accessed June 2, 2020. nelsonearthday.net/index.php.

Mock, Brentin. "Are there Two Different Versions of Environmentalism, One 'White', One 'Black'?" Mother Jones. July 31, 2014. motherjones.com/environment/2014/07/white-black-environmentalism-racism/.

Purdy, Jedediah. "Environmentalism's Racist History." New Yorker, August 13, 2015. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/environmentalisms-racist-history.

Reid, Laura. "Why Race Matters When We Talk About the Environment: An Interview with Dr. Robert Bullard." Greenpeace. March 1, 2018. greenpeace.org/usa/why-race-matters-when-we-talk-about-the-environment/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Catherine McNeur, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City, Reprint edition (Harvard University Press, 2017); Carl A. Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2015); Mark Fiege, The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Mark Dowie, Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1996). |

| 3. | The core "heroes" come from the wilderness and early conservation movements. See, for example, Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale University, 1996 [1965]); Aldo Leopold A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There (London: Oxford University Press, 1949). |

| 4. | Paul Sabin, "Environmental Law and the End of the New Deal Order," Law and History Review 33, no. 4 (November 2015): 965–1003; Jennifer Thomson, The Wild and the Toxic: American Environmentalism and the Politics of Health. (University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Keith Makoto Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists: A History of Radical Environmentalism. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). |

| 5. | Lisa Sun-Hee Park and David N. Pellow, The Slums of Aspen: Immigrants vs. the Environment in America's Eden, (New York: New York University Press, 2011); Dorceta E. Taylor, The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection (Durham, NC: Duke University Books, 2016). |