Overview

The turn of the decade marks the fiftieth anniversary of major environmental milestones: the signing of the National Environmental Policy Act, the first celebration of Earth Day, the passage of the Clean Air Act, and the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency. Central to the activist upsurge that brought about these progressive policy changes was the important and often underacknowledged environmental activism of people of color and other marginalized groups. In this brief essay, adapted from Rethinking the American Environmental Movement post-1945 (New York: Routledge Press, 2019), University of Alabama professor Ellen Griffith Spears highlights some of that activism.

Adapted from Rethinking the American Environmental Movement post-1945. London; New York: Routledge Press, 2019.

Essay

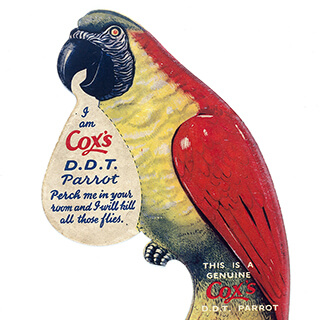

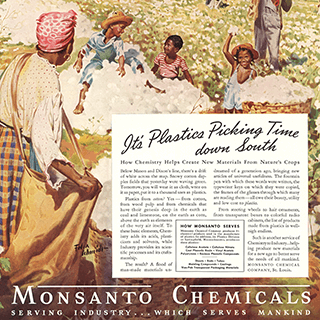

In a 2017 essay, National Museum of African American History and Culture director Lonnie Bunch noted that, like much of black history, environmental activism by people of color is often "forgotten" or "hidden in plain sight." Bunch, now director of the Smithsonian Institution, labeled this movement work unacknowledged environmentalism. Environmental reform campaigns led by people of color and other marginalized groups include not only land struggles by formerly enslaved people and by Native Americans, but also agricultural movements and the class-based mobilizations of populist agrarians. Chicano farmworker fights against poisonous pesticides are environmental battles, as are African American civil rights campaigns for equal access to recreational areas and to safe spaces in cities.1Lonnie G. Bunch III, "Black and Green: The Forgotten Commitment to Sustainability," in Living in the Anthropocene: The Earth in the Age of Humans, eds. W. John Kress and Jeffrey K. Stine (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, in association with Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2017), 83–86, 86.

Recovering this history acknowledges that people of color and the poor have shared the passion for wilderness and the natural world that motivates preservationists. In the early twentieth century, for example, African American women and men hiked Niagara Falls and cycled in Yellowstone. George Washington Carver, as we know from historian Mark Hersey's 2011 study, explicitly cast his research and practice of agroecology in terms of conservation.2Mark D. Hersey, My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

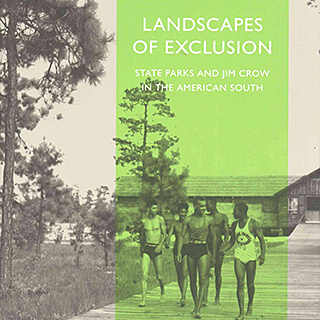

However, the benefits of environmental citizenship are not and have not been distributed equally. People of color have fought to participate in the enjoyment of nature and the benefits to health those activities offered. "[T]he color line in any guise was inherently environmental," explains historian Mark Fiege. The spatial configuration of cities and towns, reservation boundaries, Jim Crow segregation on either side of the Mason-Dixon line, the contemporary policing of racialized spaces—all can be understood not only as battle lines in freedom struggles but also as unacknowledged elements of urban ecology, a denial of mobility, a constraint on access to space. "The criminalization of urban space," as scholar Yohuru Williams explains, increasingly has been recognized as a question of environmental justice.3Mark Fiege, The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 320; Robert S. Emmett, Cultivating Environmental Justice: A Literary History of U.S. Garden Writing (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 5; Yohuru R. Williams, Rethinking the Black Freedom Movement (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 115.

The environmental justice paradigm that emerged in the 1980s expands our understanding of what issues and concerns count as environmentalism. Native American groups lobby to redress exploitation of uranium miners. Organizations such as the Black Panthers and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) identified environmental concerns not on the agenda of mainstream groups such as the need for rat eradication and demand for "community control" in urban areas. In their call for self-determination, black nationalists took up the slogan, "Free the Land."4Alondra Nelson, "The Longue Durée of Black Lives Matter," American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 10 (2016): 1734–1737, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303422; Russell Rickford, "'We Can't Grow Food on All This Concrete': The Land Question, Agrarianism, and Black Nationalist Thought in the Late 1960s and 1970s," Journal of American History 103, no. 4 (March 2017): 956–980, 957.

Social justice environmentalists have sought not just the inclusion of people of color in the history and practice of conservationism, but a fundamental reorientation of the American environmental movement's concerns and aims. Calling for equal treatment of communities of color and for full participation by marginalized social groups in environmental decision-making, environmental justice proponents emphasize questions of power and rights. Scholars have often described campaigns so rooted in broader social justice movements that they were not recognized as environmentalism. Excluded groups link their appreciation of nature and desire for healthy surroundings to a broader vision of social justice inseparable from full social and political rights.

Stimulated in part by this reorientation, new histories of environmentalism and, to a certain extent, the movement itself have begun confronting the more complex and difficult elements of the conservation movement's past. From its beginnings, conservationism echoed the nation's conflicts over race and inequality. Several prominent early conservationists were also eugenicists. White supremacy and nativism—hostility toward immigrants—were integral to the way many early conservationists understood their work. These ideas infused (and continue to infuse) debates about overpopulation, immigration, and resource policy.5Robert Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, rev. ed. (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005), 24; Jennifer Clapp and Peter Dauvergne, Paths to a Green World: The Political Economy of the Global Environment, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 246; Ben Zuckerman, "Nothing Racist About It," Globe and Mail, January 28, 2004, theglobeandmail.com/opinion/nothing-racist-about-it/article741382/.

The early campaigns for wilderness preservation are now understood not only as preserving public lands and limiting habitat destruction but also as a race-making project, defining who could enjoy the full rights of citizenship. As historian Carolyn Finney and others have argued, the designation of national parks and wilderness areas often created "white spaces" by displacing native populations and excluding racial minorities.6Carolyn Finney, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Miles A. Powell, Vanishing America: Species Extinction, Racial Peril, and the Origins of Conservation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America, 2nd ed. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016). Nevertheless, a strong, identifiable thread of social justice thought and action runs through US movements for environmental reform. Individuals involved in environmental causes have often participated in actions to oppose racial injustice, eliminate poverty, and achieve gender equality. Such alliances have been essential to the success of the environmental movement.

Struggles over segregated space that highlighted injustices offer some of the clearest examples of unacknowledged environmentalism. When the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) campaigned to desegregate the bus system and open jobs to black citizens in Alabama's capital city, five of the organization's eight primary demands presaged environmental justice themes. Laid out in a flyer entitled "Negroes' Most Urgent Needs," the MIA's concerns included "Negro Representation on the Parks and Recreation Board," "Sub-division for housing," "Congested areas, with inadequate or no fireplugs," "Lack of sewage disposals makes it necessary to resort to out-door privies, which is a health hazard," and, "Narrow streets, lack of curbing, unpaved streets in some sections."7"Negroes' Most Urgent Needs," Inez Jessie Baskin Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama, as displayed at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, http://digital.archives.alabama.gov/cdm/ref/collection/voices/id/2019. All are urban matters that would today be regarded as environmental concerns.

African American activists were often first to join forces with other people of color facing environmental threats. For example, in 1966, comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory was jailed in Washington state for participating in a "fish-in" held by the Nisqually Indians and other tribes to protest restrictions on native fishing rights. Inspired by civil rights sit-ins and organized by the Survival of the American Indian Society, these protests at Frank's Landing in Puget Sound sought to prevent overfishing by commercial fisheries and to restore native treaty rights to fish in the region's bays and streams. At issue were the tribes' ecological heritage and livelihoods, as well as treaty rights and tribal sovereignty. Dr. King telegraphed his support. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) endorsed the effort; the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the ACLU provided legal assistance.8Telegram from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Dick Gregory, Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers, Civil and Human Rights Museum, Atlanta, Georgia, on view March 14, 2015; "Gregory and Wife Guilty in Indian Fishing Protests," New York Times, December 2, 1966, 69; Charles F. Wilkinson, Messages from Frank's Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 55–56; U.S. v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312 (W.D. Wash. 1974), aff'd 520 F. 2d 676 (9th Cir. 1975). One of the most important cases in American Indian law, the decision upheld the tribes' rights to an equitable portion of the catch and co-management of the fish stocks in the Puget Sound watershed and nearby offshore waters. The Court's holding was reaffirmed in 2018. See Zultán Grossman, Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017), 37–63; and John Eligon, "'This Ruling Gives Us Hope': Supreme Court Sides with Tribe in Salmon Case," New York Times, June 11, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/11/us/washington-salmon-culverts-supreme-court.html.

An upsurge in environmental concern in the 1960s drew inspiration and tactics from civil rights organizing. Organizations such as the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) modeled their work on the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. And, a newly elected cadre of African American elected officials built alliances that helped bring attention to the ecological crisis and advance environmental reform.

Following a path pursued successfully by civil rights advocates, environmentalists turned increasingly to the federal government as guarantor of rights. Working with allies in Congress, environmentalists erected a new framework of environmental law in less than a generation, much of it during the Nixon administration. A series of telegenic disasters proved instrumental in eliciting change.

In January 1969, just days after President Richard M. Nixon took office, a blowout at a Union Oil rig spewed oil into California's Santa Barbara estuary. Six months later, in Cleveland, Ohio, the Cuyahoga River, which flowed past the city before dumping its contents into Lake Erie, caught fire. Oil slicks and industrial wastes from innumerable factories and refineries upstream had left the water so polluted that fires had become a frequent occurrence. This particular fire brought the city's mayor to the scene and with him the national press. Cleveland's mayor in 1969 was Carl Stokes, the first African American elected to head a large US city. Not just Cleveland, but the nation faced "a crisis in the urban environment," said Stokes, "a crisis of immense proportions." With the burning river as his backdrop, Stokes linked racial progress and anti-pollution measures.9David Stradling and Richard Stradling, Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 146, 79, 194.

Public outcry over the Santa Barbara oil spill and the Cuyahoga fire pressured Congress to act, passing the National Environmental Policy Act, which President Nixon signed on January 1, 1970. NEPA did not create the EPA, as some assume; that was accomplished by an executive order approved by Congress later that year. The law did establish the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to advise the President. NEPA also gave citizens valuable tools for addressing environmental problems, mandating public participation in the permitting process. Any proposal for a large development would require an environmental impact statement (EIS) on the likely ecological impact as well as alternative proposals—say, fewer units, fewer trees destroyed, or substitute drainage plans. Developers and the permitting agencies were not required to choose the alternative with the least impact, but the new procedures gave environmental advocates a forum for raising objections and additional time for mobilizing opposition to particularly devastating projects. Considered one of the nation's most effective environmental laws, NEPA has been "emulated in various degrees by almost half the states and by an estimated 80 or more countries abroad."10John McCormick, Reclaiming Paradise: The Global Environmental Movement (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989), 58; Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring, 180; Lynton Caldwell, "Implementing NEPA: A Non-Technical Political Task," in Environmental Policy and NEPA: Past, Present, and Future, eds. Ray Clark and Larry W. Canter (Boca Raton, FL: St. Lucie Press, 1997), 25–50, 37.

Postscript

NEPA's longstanding requirements for public participation in environmental policymaking are being directly targeted by the Trump administration. In January 2020, the Trump EPA proposed new rules that would set tight time limits on environmental assessments, limit the types of projects required to complete a full EIS, and effectively exclude consideration of a proposed project's indirect and cumulative effects on climate. Vulnerable communities could be disproportionately harmed by these regulatory changes. Reversing such policies will require even more robust coalitions than those that resulted in the passage of environmental laws in the first place.

About the Author

Ellen Griffith Spears is an associate professor in the interdisciplinary New College and the Department of American Studies at the University of Alabama. She is author of the award-winning Baptized in PCBs: Race, Pollution, and Justice in an All-American Town (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Cover Image Attribution:

African American soldiers pushing their bicycles up the side of Minerva Terrace at Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park, Montana, October 7, 1896. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center and Montana Memory Project.Recommended Resources

Text

Clark, Ray and Larry W. Canter, eds. Environmental Policy and NEPA: Past, Present, and Future. Boca Raton, FL: St. Lucie Press, 1997.

Finney, Carolyn. Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Hersey, Mark D. My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Kress, W. John and Jeffrey K. Stine, eds. Living in the Anthropocene: The Earth in the Age of Humans. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, in association with Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2017.

Powell, Miles A. Vanishing America: Species Extinction, Racial Peril, and the Origins of Conservation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Rickford, Russell. "'We Can't Grow Food on All This Concrete': The Land Question, Agrarianism, and Black Nationalist Thought in the Late 1960s and 1970s." Journal of American History 103, no. 4 (2017): 956–980.

Web

"The American Environmental Justice Movement." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed January 30, 2020. https://www.iep.utm.edu/enviro-j/.

Brady, Lisa M., ed. "Race, Justice, and Civil Rights." Environmental History 2nd virtual ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. Digital Journal. https://academic.oup.com/envhis/pages/race_justice_and_civil_rights.

Britton-Purdy, Jedediah. "Environmentalism Was Once a Social-Justice Movement: It Can Be Again." The Atlantic, December 7, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/12/how-the-environmental-movement-can-recover-its-soul/509831.

Krause, Dunja and Doreen Akiyo Yomoah. "Environmental Justice in the United States—What's Missing?" United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Accessed January 30, 2020. http://www.unrisd.org/unrisd/website/newsview.nsf/(httpNews)/83877A520A40C5F7C1258256005235AF.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. "Race, Class, Gender, and American Environmentalism," by Dorceta E. Taylor. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-534. Portland, OR: Pacific Northwest Research Station, 2002. https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/gtr534.pdf.

U.S. Department of Energy. "Environmental Justice History" (web page). Office of Legacy Management. Accessed January 30, 2020. https://www.energy.gov/lm/services/environmental-justice/environmental-justice-history.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Lonnie G. Bunch III, "Black and Green: The Forgotten Commitment to Sustainability," in Living in the Anthropocene: The Earth in the Age of Humans, eds. W. John Kress and Jeffrey K. Stine (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, in association with Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2017), 83–86, 86. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Mark D. Hersey, My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011). |

| 3. | Mark Fiege, The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 320; Robert S. Emmett, Cultivating Environmental Justice: A Literary History of U.S. Garden Writing (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 5; Yohuru R. Williams, Rethinking the Black Freedom Movement (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 115. |

| 4. | Alondra Nelson, "The Longue Durée of Black Lives Matter," American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 10 (2016): 1734–1737, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303422; Russell Rickford, "'We Can't Grow Food on All This Concrete': The Land Question, Agrarianism, and Black Nationalist Thought in the Late 1960s and 1970s," Journal of American History 103, no. 4 (March 2017): 956–980, 957. |

| 5. | Robert Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, rev. ed. (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005), 24; Jennifer Clapp and Peter Dauvergne, Paths to a Green World: The Political Economy of the Global Environment, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 246; Ben Zuckerman, "Nothing Racist About It," Globe and Mail, January 28, 2004, theglobeandmail.com/opinion/nothing-racist-about-it/article741382/. |

| 6. | Carolyn Finney, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Miles A. Powell, Vanishing America: Species Extinction, Racial Peril, and the Origins of Conservation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America, 2nd ed. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016). |

| 7. | "Negroes' Most Urgent Needs," Inez Jessie Baskin Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama, as displayed at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, http://digital.archives.alabama.gov/cdm/ref/collection/voices/id/2019. |

| 8. | Telegram from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Dick Gregory, Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers, Civil and Human Rights Museum, Atlanta, Georgia, on view March 14, 2015; "Gregory and Wife Guilty in Indian Fishing Protests," New York Times, December 2, 1966, 69; Charles F. Wilkinson, Messages from Frank's Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 55–56; U.S. v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312 (W.D. Wash. 1974), aff'd 520 F. 2d 676 (9th Cir. 1975). One of the most important cases in American Indian law, the decision upheld the tribes' rights to an equitable portion of the catch and co-management of the fish stocks in the Puget Sound watershed and nearby offshore waters. The Court's holding was reaffirmed in 2018. See Zultán Grossman, Unlikely Alliances: Native Nations and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017), 37–63; and John Eligon, "'This Ruling Gives Us Hope': Supreme Court Sides with Tribe in Salmon Case," New York Times, June 11, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/11/us/washington-salmon-culverts-supreme-court.html. |

| 9. | David Stradling and Richard Stradling, Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 146, 79, 194. |

| 10. | John McCormick, Reclaiming Paradise: The Global Environmental Movement (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989), 58; Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring, 180; Lynton Caldwell, "Implementing NEPA: A Non-Technical Political Task," in Environmental Policy and NEPA: Past, Present, and Future, eds. Ray Clark and Larry W. Canter (Boca Raton, FL: St. Lucie Press, 1997), 25–50, 37. |