Overview

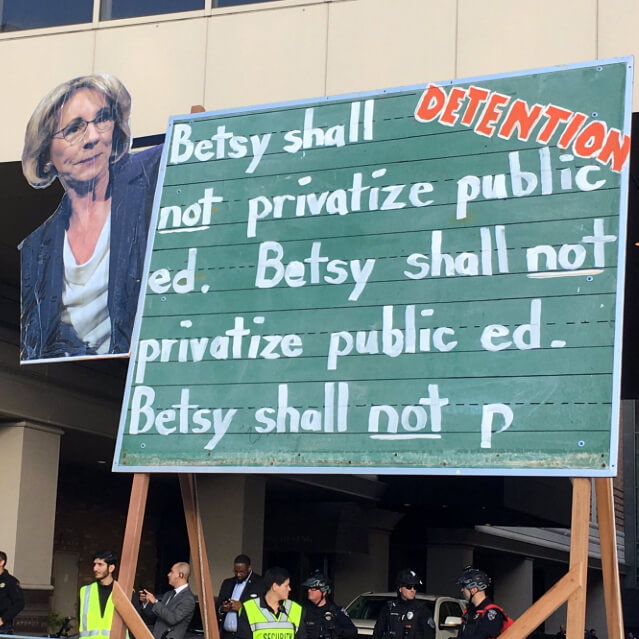

On the seventieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education—the US Supreme Court decision outlawing racial segregation in the nation’s public schools—Steve Suitts reveals an emerging, seismic shift in how southern states in the United States are leading the nation in adopting universal private school vouchers. Suitts warns that this new “school choice” movement will reestablish a dual school system not unlike the racially separate, unequal schools which segregationists attempted to preserve in the 1960s using vouchers.

Introduction

On the seventieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed racial segregation in the nation’s public schools, the states of the southern US are pushing to reestablish publicly financed, dual school systems—one primarily for higher-income and white children and the other primarily for lower-income and minority children. This seismic shift in how states fund K–12 education through universal vouchers isn’t confined to the South. But it is centered among the states that once mandated racially separate, unequal schools and where segregationists in the 1960s attempted to use private school vouchers to evade the watershed US Supreme Court decision.

More than thirty-five states have created voucher programs to send public dollars to private schools. At least twenty, including most in the South, have adopted or are on a path to enact legislation making state-funded “Educational Savings Accounts” (ESAs)—the newest type of voucher approach—available to all or most families who forego public schools. These families can use the funds to send their children to almost any K–12 private school, including home-schooling, or purchase a wide range of educational materials and services, such as tutoring, summer camps, and counseling.

In recent times, private school vouchers were pitched to the public for the purpose of giving a targeted group of disadvantaged children new educational options, but legislatures are now expanding eligibility and funding for vouchers to include advantaged students. By adopting universal or near universal eligibility for ESAs, states will be obligating tens of billions of tax dollars to finance private schooling while creating a voucher system for use by affluent families with children already attending or planning to attend private school.

States are rushing to enact ESAs while they still have the last of huge federal COVID appropriations to distribute among public schools. This timing allows ESAs' sponsors—Republican legislative leaders and governors—to entice once-reluctant, rural legislators to support vouchers. It also camouflages the severe fiscal impact this scheme will have on routinely underfunded public schools after the special federal funds run out.

The states adopting ESAs are also structuring this emerging, publicly funded, dual system so that private schools and homeschooling remain free of almost all regulations, academic standards, accountability, and oversight. These sorts of rules and regulations are always imposed by state legislatures on public schools and are understood as essential to protect students and to advance learning. Even as legislatures are adding restrictive laws on how local public schools teach topics involving race, sex, ethnicity, and gender they are providing new state funding for private schools and home-schooling that will enable racist, sexist, and other bigoted teaching.

If state legislatures succeed in establishing and broadening this dual, tax-funded system of schools, the tremors will transform the landscape of US elementary and secondary education for decades to come. Calling for “freedom of choice,” a battle cry first voiced by segregationists who fought to overturn the Brown decision,1Steve Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement,” Southern Spaces, June 4, 2019, https://southernspaces.org/2019/segregationists-libertarians-and-modern-school-choice-movement. Available in book form as Overturning Brown: The Segregationist Legacy of the Modern School Choice Movement (Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020). predominantly white Republicans will take states back to a future of separate and unequal education.

The Universal Voucher System

By the seventieth anniversary of Brown, five states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina) have enacted ESA programs that allow all or a vast majority of families with school-age children to send their children to private schools with state funds that equal or closely match the states’ per pupil expenditures for public schools. South Carolina adopted a “pilot” ESA last year, and a bill making its program permanent has already passed one chamber. The lower house of the Louisiana legislature passed a bill for a statewide universal ESA program to start next year, but the state senate is likely to delay adoption for another year to confirm estimated costs. Both states have governors who are likely to push adoption again next year.2The best source for the current status and terms of voucher and ESA legislation, including those bills passed and pending in 2023–2024, can be found at FutureEd, an independent think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. https://www.future-ed.org/legislative-tracker-2024-state-private-school-choice-bills/; Seanna Adcox, “‘Universal’ school choice approved in SC House before pilot even begins,” South Carolina Daily Gazette, Mar. 21, 2024, https://scdailygazette.com/2024/03/21/universal-school-choice-approved-in-sc-house-before-pilot-even-begins/; Greg LaRose, “Lawmakers advance education savings accounts, parents’ curriculum choice,” Louisiana Illuminator, Mar. 20, 2024, https://lailluminator.com/2024/03/20/education-savings-accounts/; Greg LaRose, “High price tag for education savings accounts leads to proposal overhaul,” Louisiana Illuminator, May 2, 2024, https://lailluminator.com/2024/05/02/education-savings-account/.

The Tennessee legislature adjourned in April without passing either of two pending universal ESA bills—only because Governor Bill Lee and legislative leaders failed to agree on which voucher bill to enact. They vow to pass legislation next session. In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott used campaign funds from a Pennsylvania billionaire in the state’s Republican primary to defeat a handful of legislators who blocked his ESA bill last year. Abbott expects to defeat the two remaining state house members who failed to vote for his legislation—giving him the number he needs to pass his bill, while sending a political message that will keep his supporters in line.3Sam Stockard and Adam Friedman, “Tennessee’s statewide school voucher bill dead, but not forgotten,” Tennessee Outlook, Apr. 22, 2024, https://tennesseelookout.com/2024/04/22/tennessees-statewide-school-voucher-bill-dead-but-not-forgotten/. Karen Brooks Harper, “School voucher supporters bask in primary wins, say goals are within reach,” Texas Tribune, Mar. 6, 2024, https://www.texastribune.org/2024/03/06/texas-primaries-vouchers-school-choice/; Renzo Downey, “Gov. Greg Abbott says Texas is two House votes away from passing school vouchers,” Texas Tribune, Mar. 20, 2024, https://www.texastribune.org/2024/03/20/greg-abbott-tppf-vouchers-primary-runoff/. In identifying ESAs, this essay does not distinguish between those funded by state appropriations and those funded by state tax credits.

Only two southern states have not yet joined this reactionary movement. Republicans in Virginia’s legislature introduced a half-dozen bills to establish universal ESAs during the last two sessions but were stymied by bipartisan concerns about how vouchers benefited the wealthy and drained funds from public schools, and by Democrats who narrowly control both houses. In prior years, the Virginia legislature passed bills establishing limited ESAs but those too were blocked by the state’s last two Democratic governors.4Joe Landcaster, “Virginia Is Considering 4 Different School Choice Bills,” Reason, Jan. 22, 2023, https://reason.com/2023/01/22/virginia-is-considering-4-different-school-choice-bills/; Megan Pauly, “Wealthiest Virginians are benefiting most from contributions to school voucher program,” VPM News, July 11, 2022, https://www.vpm.org/news/2022-07-11/wealthiest-virginians-are-benefiting-most-from-contributions-to-school-voucher/.

In Mississippi, once the nation’s symbol of truculent political opposition to Brown and home to a vast number of segregation academies set up to evade school desegregation, Republicans control both legislative houses and the governor’s mansion. But, at the end of its 2024 session, the legislature failed to enact both a proposed new $40 million voucher program and a near-universal ESA bill that Governor Tate Reeves sought.5Suitts, Overturning Brown, 29–32; Bracey Harris, “Reckoning with Mississippi’s ‘segregation academies’,” The Hechinger Report, Nov. 29, 2019, https://hechingerreport.org/reckoning-with-mississippis-segregation-academies/; Russ Latino, “New Legislation Would Create Universal School Choice Program in Mississippi by 2029,” Magnolia Tribune, Feb. 20, 2024, https://magnoliatribune.com/2024/02/20/new-legislation-would-create-universal-school-choice-program-in-mississippi-by-2029/; Bobby Harrison, “House advances bill that would establish close study of universal school vouchers,” Mississippi Today, Mar. 5, 2024, https://mississippitoday.org/2024/03/05/house-committee-universal-vouchers/; Bobby Harrison, “Bill increasing tax credits for private schools defeated at end of session,” Mississippi Today, May 7, 2024, https://mississippitoday.org/2024/05/07/private-schools-tax-credits-mississippi-legislature/.

Why is Mississippi currently an exception to the rush to ESAs? First, the state is more rural and poorer than any other southern state, with vastly underfunded public schools and most of its private school children in a few suburban and urban areas. The Democrats who oppose vouchers in the legislature comprise a larger number than in other states (the Black population accounts for the largest percentage of any state). Significant, too, is the work of effective public interest lobbyists in Mississippi, led on school issues by an interracial coalition, The Parents Campaign. The group's director, Nancy Loome, has built a rare reputation on both sides of the legislative aisle as a trusted, honest voice for school children.

Border South states have already joined the separate and unequal movement. In 2021, Oklahoma and West Virginia passed ESA programs that have eligibility guidelines allowing almost every family with school-age children to receive state funding for private schooling and related educational expenses. Missouri expanded its tax credit ESA voucher program to include students across the state in four-person households with incomes up to $147,000. Kentucky passed a tax credit voucher program in 2021, but its supreme court held that the state constitution prohibits financing nonpublic schools. In 2024, the Republican-led legislature passed a bill authorizing a referendum to change the state constitution to permit ESAs.6For the bills terms, see FutureEd, https://www.future-ed.org/legislative-tracker-2024-state-private-school-choice-bills/; Amelia Ferrell Knisely, “Public schools likely to lose $21M after thousands of students left for Hope Scholarship,” West Virginia Watch, Dec. 13, 2023, https://westvirginiawatch.com/2023/12/13/public-schools-likely-to-lose-21m-after-thousands-of-students-left-for-hope-scholarship/; Annelise Hanshaw, “Opposition remains for sprawling education bill expanding Missouri private school tax credits,” Missouri Independent, Mar. 28, 2024, https://missouriindependent.com/2024/03/28/opposition-remains-for-sprawling-education-bill-expanding-missouri-private-school-tax-credits/; McKenna Horsley, “‘Game changer:’ Amendment for public dollars to nonpublic schools clears General Assembly,” Kentucky Lantern, Mar. 15, 2024, https://kentuckylantern.com/2024/03/15/game-changer-amendment-for-public-dollars-to-nonpublic-schools-clears-general-assembly/.

Arizona and Indiana are the leading states for voucher programs outside the South. In 1997, Arizona was one of the earliest adopters. Its ESA now costs more than $900 million a year. Indiana’s near-universal program, enacted in 2022, costs roughly $500 million in 2024.7Beth Lewis and Karen Kirsch, “One year in, Arizona’s universal school vouchers are a cautionary tale for the rest of the nation,” AZMirror, Dec. 11, 2023, https://azmirror.com/2023/12/11/one-year-in-arizonas-universal-school-vouchers-are-a-cautionary-tale-for-the-rest-of-the-nation/; Casey Smith, “Indiana’s ‘school choice’ voucher program grew 20% last year—with more growth coming” Indiana Capital Chronicle, June 14, 2023, https://indianacapitalchronicle.com/2023/06/14/indianas-school-choice-program-grew-20-percent-last-year-with-more-growth-coming/.

The remaining states with ESAs are Kansas, Ohio, Utah, Iowa, New Hampshire, and Wyoming. By 2027, approximately 86 percent of Kansas families could be eligible for a voucher. In Utah, families with a child eligible to attend public schools can receive up to $8,000. Legislation introduced in 2024 would increase the ceiling to $150 million. Iowa’s ESA cost over $100 million in its first year and 60 percent of the recipients were already attending private schools. The New Hampshire ESA program is more restrictive, spending less than $25 million in 2023 and permitting only children from households with incomes below 350 percent of poverty to participate, although school choice advocates are pushing for expansion. Wyoming’s Republican legislature voted to allow families with household incomes of up to $146,000 to receive state funds, but Republican Governor Mark Gordon used a line-item veto to cut the eligibility down to 150 percent of poverty since the state constitution prohibits funding private individuals or organizations “except for the necessary support of the poor.”8Author’s calculations based on the bills’ terms and each state’s median income; FutureEd. Also see Jay Waagmeester, “County-by-county distribution of education savings accounts released,” Iowa Capital Dispatch, Aug. 8, 2023.

So far, sixteen states have set up ESAs to publicly finance private school attendance, home-schooling, and a range of educational services available to a majority of the states’ school-age children. Southern states are leading this movement by undertaking a classic bait and switch—first selling the public on voucher programs to help poor and disadvantaged students in “chronically failing public schools,” and then building and publicly financing an alternative, dual system of private schooling.

The historical context is shameful. Five of the southern states that now have universal vouchers also enacted open-ended vouchers in the 1960s—attempting to defeat Brown’s mandate for school desegregation. All but four of the states that have already embraced publicly financed ESAs were the only states authorizing segregated public schools on the eve of the Supreme Court’s decision.9Suitts, Overturning Brown, 18–53, 87–89; Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement,”; Pauli Murray, States' Laws on Race and Color (Cincinnati, OH: Women's Division of Christian Service of the Methodist Church, 1951). Indiana had school segregation laws from 1869 until 1949, when five years before the Brown decision the legislature revoked the laws, See Murray, 145–147. The eighteen states are the eleven states of the South: West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma in the Border South; Kansas, Indiana, Arizona, and Wyoming.

The fiscal impact of this rush to fund private schooling will be devastating to public schools. In 2018, all fifty states allocated $2.6 billion to finance private school vouchers. In 2021, legislatures increased the total amount to $3.3 billion and more recently to over $6 billion. If the eleven southern states enact the bills currently adopted or pending in their legislatures, their total funding for vouchers will be as much as $6.8 billion in 2025–26 and, according to independent estimates, as much as $20 billion for private schooling in 2030. This sum would equal the total state funds to public schools among six southern states in 2021.10Suitts, Overturning Brown, 3; EdChoice, The ABCs of School Choice, 2024, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2024-ABCs-of-School-Choice.pdf; author's computations based on the provisions of enacted and pending bills, fiscal notes accompanying legislation and independent estimates by non-profits in the southern states.

The Past Is Future

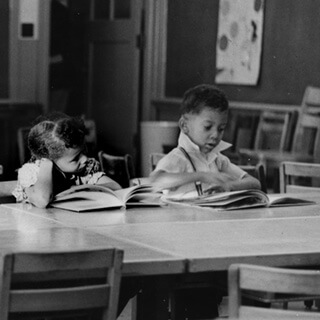

Segregationists’ attempts to use private schools to prevent the implementation of Brown shaped the demography of private school enrollment. After the 1954 decision, enrollment in southern private schools accelerated. With federal court enforcement of Brown, private school growth exploded in the 1960s and 1970s as white families, especially in areas with large Black populations, fled public schools. This was the era of “segregation academies”—private schools created in response to federal court orders to desegregate local public schools. With little or no attempt to hide their intent to evade Brown, seven southern legislatures enacted voucher programs providing families with tax dollars to send their children to private schools. The other four states of the former Confederacy came close to adopting such programs, but abandoned consideration once the federal courts invalidated voucher programs. Adopted as an effort to allow public funds to “fund the child,” Georgia voluntarily defunded its vouchers after segregationist lawmakers realized that they were mostly subsidizing well-to-do families whose children were already attending private schools. In Louisiana, both white and Black families were provided private school vouchers before the federal courts voided the program.11Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement.”

Southern states’ private school enrollment quickened across the decades, especially in the 1990s as population, economy, and personal income markedly increased. To retain a non-profit, federal tax exemption, segregation academies ditched their strict, all-white admission policies, and reoriented their appeal as places of religious education or of higher educational standards. Other private schools became more willing to admit children of color as a new generation of white people was less indoctrinated by received habits, institutions, leaders, and media on the necessity and virtue of total segregation. Whatever non-racial rationale private schools adopted, the vast majority maintained a common character: “These are schools for whites,” observed a group of scholars in the 1970s. “The common thread that runs through them all, Christian, secular, or otherwise, is that they provide white ground to which blacks are admitted only on the school’s terms if at all.”12David Nevin and Robert E. Bills, The Schools that Fear Built: Segregationist Academies in the South (Washington, DC: Acropolis Books, 1976), 11.

Private and Public: Vastly Disparate Students

The character of most southern private schools has persisted, but, beginning in the 1990s, the student population of the South’s public schools began to change. Today, the southern states’ private schools remain predominately white and their public schools are predominately non-white, serving children of color. In 2021 (the latest comparable data), white students comprised 63 percent of the South’s private school enrollment and only 39 percent of the public schools. Black and Hispanic children constituted 53 percent of all students in public schools but less than half that proportion—26 percent—in the private schools of the eleven states.13Private school enrollment retrieved and computed from National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), accessed at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pss/privateschoolsearch/. Public school enrollment taken from NCES’ Table 203.70 of 2023 Digest of Education Statistics, accessed at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2023menu_tables.asp.

Income also separates the public and private schools as worlds apart. Private school students come from homes with vastly higher incomes than public school students. The median incomes of private school households in Georgia, Florida, Louisiana North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virgina have been from 170 percent to nearly 200 percent greater than incomes of public school households over the last two decades. A recent scholarly, national study found that enrollment of higher-income students in private schools had increased over prior decades.14Jacob Fabina, Erik L. Hernandez, and Kevin McElrath, “School Enrollment in the United States: 2021,” American Community Survey Reports, US Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2023; Bruce D. Baker, Danielle Farrie, David Sciarra, Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card, 2012, 2014, 2017, “Coverage” appendices; R.J Murnane and Sean Reardon, “Long-Term Trends in Private School Enrollments by Family Income,” AERA Open 4, no. 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858417751355. The Murname and Reardon study measured the Census South.

As private school enrollment has become wealthier, public school enrollment has become poorer. By 2006, a majority of the South’s public school students came from low-income households, and in 2013, for the first time in recent history, a majority of the nation’s public school children came from low-income households. Despite continued growth in the US economy, these patterns persist. Fifty-two percent of the public school students in the eleven-state South were eligible for free or reduced school meals in 2021, due in large part to the enrollment of so many low-income children. Nationwide, the rate was 49 percent, only slightly down from more than 50 percent during the two prior years.

A sizable number of public school children also have special needs that involve extraordinary educational challenges for teachers and schools. The southern states have almost 40 percent of the nation’s five million school children who are English learners. Students with disabilities (IDEA) range from one in every ten students in Texas to one in every six students in Arkansas public schools. On average, one child out of every fifty in the South’s public schools is homeless.15Steve Suitts, A New Majority: Low Income Students in the South’s Public Schools, Southern Education Foundation, 2008, https://southerneducation.org/publications/newmajority/; Steve Suitts, A New Majority Update: Low Income Students in the South and Nation, Southern Education Foundation, 2013, https://southerneducation.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/new-majority-update-bulletin.pdf; computations from Tables 102.40, 204.10, 204.20, 204.70, 204.75d, “Digest of Education Statistics, 2022,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2022menu_tables.asp.

There is no reliable data on the number of children with special needs enrolled in private schools. A small number were established to serve special needs students, but the vast majority do not. As a matter of law and mission, most private schools maintain no responsibility to educate disadvantaged students.

Vouchers Worsen School Disparities in a Dual System

Wherever states have abandoned narrow, targeted voucher programs, the expanded public funding has usually been grabbed by the higher-income households, often with children already attending private schools. In 2023, Education Week magazine, which has impartially covered K–12 schools for more than forty years, reported that in states with recently expanded voucher programs a “majority of students participating in these programs were already enrolled in private schools or were homeschool students prior to signing up for the newly expanded, publicly funded education subsidy."16Mark Lieberman, “Most Students Getting New School Choice Funds Aren’t Ditching Public Schools," Education Week, Oct. 4, 2023, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/most-students-getting-new-school-choice-funds-arent-ditching-public-schools/2023/10.

During Arkansas’ first year of financing universal ESAs, “95% of the students receiving vouchers” did not attend public schools before receiving the state money. And in four other states that have enacted near-universal ESAs, including Florida, a majority of the new households receiving vouchers have children already attending private schools.17Arkansas Department of Education, LEARNS, Education Freedom Account Annual Report, 2023–2024, https://arktimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/EFA-Transparency-Report37.pdf; “Iowa’s Students First Education Savings Account program generates more than 29,000 applications,” press of Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds, July 6, 2023, https://governor.iowa.gov/press-release/2023-07-06/iowas-students-first-education-savings-account-program-generates-more; Robin Opsahl, “More than 29,000 apply for Iowa private-school funds in first year,” Iowa Capital Dispatch, July 6, 2023, https://iowacapitaldispatch.com/2023/07/06/more-than-29000-apply-for-iowa-private-school-funds-in-first-year; Ethan Dewitt, “Most education freedom account recipients not leaving public schools, department says,” New Hampshire Bulletin, Mar. 22, 2022, https://newhampshirebulletin.com/briefs/mosteducation-freedom-account-recipients-not-leaving-public-schools-department-says/; News Service Florida, “New report shows nearly 123,000 new students received Florida school vouchers in 2023,” NBC 6 South Florida, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/new-report-shows-nearly-123000-new-students-received-florida-school-vouchers-in-2023/3112869; Florida Department of Education (2023). "Florida’s Private Schools 2022–23: School Year Annual Report," https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7562/urlt/PS-annualReport2023.pdf; Alec MacGillis, “Private Schools, Public Money: School Leaders Are Pushing Parents to Exploit Voucher Programs,” ProPublica, Jan. 21, 2024, https://www.propublica.org/article/private-schools-vouchers-parents-ohio-public-funds.

Data on household income among new ESA recipients is not widely available, but an analysis by Ohio’s former chair of the state house education committee finds that the state’s near-universal voucher programs is subsidizing private school tuition for families in higher income brackets, and that nine of ten of the new recipients have been white. Arizona does not collect income data from its rapidly expanded universal ESA, but Princeton sociologist Jennifer Jennings found in 2024 that “Arizona’s school vouchers are subsidizing its most fortunate families, reinforcing existing disparities rather than mitigating them.” In Florida, the lastest available numbers show that two out of every three new recipients in its universal voucher programs had incomes above 185 percent of poverty. As many as 44 percent had incomes no less than 400 percent above the poverty line.18Stephne Dyer, “Ohio's Disastrous Voucher Explosion,” Tenth Period, Nov. 29, 2023, https://10thperiod.substack.com/p/ohios-disastrous-voucher-explosion?subscribe_prompt=free; Jennifer Jennings, “Arizona’s school vouchers are helping the wealthy and are widening educational opportunity gaps,” Arizona Mirror, Jan. 12, 2024, https://azmirror.com/2024/01/12/arizonas-school-vouchers-are-helping-the-wealthy-and-are-widening-educational-opportunity-gaps; “Transparency in Scholarship Programs,” Step Up for Students via Florida Phoenix Sep. 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yyl80Jbs9mU6GlV1ktA6zZg8GUjLnsP4/view. The Arizona Common Sense Institute argues that its zip code analysis shows that the state’s ESAs are assisting mostly middle-class families but their analysis lumps together zip codes with median household incomes with those more than twice the state median. In Florida, Step Up for Students expanded the grouping of voucher recipients—the lowest income category showing recipients’ income as high as 185 percent of poverty. Glenn Farley and Kamryn Brunner, Universal ESA’s: Where We Are and Where We Are Going, Arizona Common Sense Institute, May 2023, https://commonsenseinstituteaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CSI-Report-_Universal-ESAs_May-2023-2.pdf; Glenn Farley, Growth and Change: How One Year of Universal Empowerment Scholarship Accounts Has (and Has Not) Altered Arizona’s K–12 Landscape, Arizona Common Sense Institute, April 2024, https://commonsenseinstituteaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CSI_REPORT_ESA_GROWTH_APRIL_2024.pdf.

It has been evident for years that wealthier households are the primary beneficiaries of open-eligibility tax credit voucher programs. In 2023 the non-profit Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy examined programs in three states that permitted any family to divert state taxes to private school vouchers. Ninety-nine percent of all voucher tax credits in Louisiana and 87 percent in Virginia went to families with annual incomes over $200,000. In Arizona, it was 60 percent. In Georgia, $100 million can now be taken annually from the treasury through state tax credit for funding private school vouchers, and higher-income families have received the majority of the vouchers since 2013. The actual number may be much greater as the program has been plagued by irregularities, deceit, and misrepresentations by private groups distributing the tax credit vouchers. The Georgia Department of Revenue does not use tax records to verify the self-reporting of those receiving the tax credits or vouchers.19Carl Davis, Tax Avoidance Continues to Fuel School Privatization Efforts, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Mar. 3, 2023, https://itep.org/tax-avoidance-fuels-school-vouchers-privatization-efforts/; author’s computations from annual Qualified Education Expense Credit Report, Georgia Department of Revenue, 2013–2021, https://dor.georgia.gov/calendar-year-qualified-education-expense-credit-report; Steve Suitts and Katherine Dunn, A Failed Experiment: Georgia's Tax Credit Scholarships for Private Schools (Summary Report), Southern Education Foundation, 2008, https://southerneducation.org/publications/a-failed-experiment; Nancy Badertscher, “Group targets tax credit scholarships - Revenue Department asked to stem students from private schools,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 22, 2011, B-2; Steve Suitts, “Program encourages deception and helps those who don't need it,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 5, 2011, A-13.

Even with vouchers, few low-income families in the South can afford to keep their children in K–12 private schools. The average cost of private school tuition in ten of eleven southern states exceeds those states’ per-pupil funding of public schools. In other words, even if a voucher equals the state per pupil allocation for public school, it is not enough to match the private school tuition. After including additional expenses of attending a private school—books, supplies, uniforms, technology, athletics, and field trips—the total average cost in all southern states except Arkansas exceeds the state per pupil appropriation. In Texas, that total cost is more than $9,000 over the state’s per pupil public school appropriation. It is more than $2,300 in Mississippi.20Calculations based data on average private tuition prices by state and other costs reported at Raise Right website, https://www.raiseright.com/blog/how-much-do-private-schools-cost, and Prosperity for America website, https://www.prosperityforamerica.org/average-private-school-tuition/. Data on state revenue for state per pupil revenue is found at “2021 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data, US Census. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/school-finances/secondary-education-finance.html. These back-of-the envelope calculations capture the real-life financial barriers many families will encounter if they rely on an ESA voucher to send a child to a private school, and the calculations don’t even include cost of transportation, something that few private schools provide and is far beyond the resources of most low-income families.

The emerging ESAs are apparently designed for higher-income families that can already afford to pay all or much of the cost of private schooling. Wealthy families can use these vouchers to cover tuition costs and a wide range of expenses. As in several other states, Alabama’s vouchers can go toward tuition, textbooks, fees, after-school care, summer education programs, private tutoring, curriculum and instructional materials, online learning, educational software and applications, standardized assessments, including college admissions tests and advanced placement exams, and college prep courses.

The South Cannot Afford a Dual School System

Southern states, while serving a large proportion of disadvantaged children, provide among the lowest per pupil funding in the nation to their public schools. Any given K–12 student in the South received on average $5,831 less for education during 2021–2022 than a student in public school elsewhere in the United States. Public school children in North Carolina, which ranks 48th in state and local funding, received nearly $7,500 less per child than what the rest of the nation provides.

This pattern of underfunding public schools is longstanding and was aggravated over decades, in large part, by the fact that the southern states maintained separate, unequal, dual school systems.21Steve Suitts, “The South: America’s Legacy of Gross Disparities in Funding Education,” No Time to Lose: Why America Needs an Education Amendment to the Constitution, Southern Education Foundation, 2009, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED524094.pdf. And the legacy persists. A recent study by University of Miami Professor Bruce Baker and his colleagues found no less than three out of every four public school districts in the South were chronically underfunded by national standards of need and resources.22Bruce D. Baker, Matthew Di Carlo, and Mark Weber, The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems, Jan. 2024, https://www.schoolfinancedata.org/the-adequacy-and-fairness-of-state-school-finance-systems-2024/.

States will soon realize the damage of these disparities. The vast federal funds that were appropriated shortly after the COVID epidemic to shore up schools will run out in 2024. Governors and state legislatures have allocated these temporary funds as if they were state appropriations and often have been able to increase public school funding using federal funds. As that funding is exhausted, public schools in the southern states will suffer extraordinary shortfalls—more so than any other area of the United States.

Approximately nine percent of Louisiana’s education budget across the last three years has been financed with federal funds, almost all of which will be spent by 2025.23Joanna LeFebvre and Sonali Master, Expiration of Federal K–12 Emergency Funds Could Pose Challenges for States, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Feb. 2024, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/2-28-24sfp.pdf. The legislature will be forced to cut K–12 education funding and/or raise additional revenue. If Louisiana's legislature enacts the pending universal ESA it could add more than $65 million in expenses by 2026, and by independent estimates, as much as a half a billion dollars in annual expenditures to the state education budget by 2030.24“Expanding School Choice: Education Savings Accounts Raise Cost, Accountability Concerns,” Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana, https://parlouisiana.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/PAR-Commentary-Expanding-School-Choice-1.pdf.

Such grim estimates extend to all states that have enacted or are moving to adopt universal ESAs, including Arizona where 6.9 percent of the state’s recent annual education appropriations will be lost. Yet the fiscal calamities will happen foremost in the southern states where federal funds have constituted an average of 6.4 percent of annual state education spending—and as much as 10.5 percent in Mississippi.

According to ERS, a consulting firm that collaborates with urban school districts, children in fifteen states will be hit hardest as the federal government’s COVID funding ends.25“Here’s Why Some States Are Facing a Steeper ESSER Funding Cliff in 2024,” ERS, Mar. 2023, https://www.erstrategies.org/tap/analysis-esser-funds-fiscal-cliff-by-state/#factor3. Nine of these are southern states, with Florida falling just outside the list. Among the states that will be hardest hit, all except New Mexico have or are currently considering ESA voucher plans.

Replacing $41.5 billion in special federal funding during the last three years will be a daunting challenge for southern states, especially since they also received billions of dollars from other federal COVID relief funding for health care, roads, transportation, and childcare. These funds are also ending. Without massive cutbacks in funding public schools and services, how can the southern states meet this crisis while spending hundreds of millions financing new ESA vouchers in support of a separate system of private schooling? It’s a fool’s errand that will involve educational and financial catastrophe for all but the South’s upper-income households, for whom ESAs will provide a nice subsidy. For public school children, especially most low-income and minority children, it is the making of a disaster.

Dismantling Public Schools

Perhaps it is the aim of some school choice backers who are pushing for a state-financed system of universal vouchers to incapacitate the public education system’s mission and mandate to serve all students with equal educational opportunities. In April 2024, a lead sponsor of universal ESA vouchers in the Tennessee legislature, Republican Scott Cepicky, was caught on tape privately telling home-school parents that his goal for the state’s public schools was to “throw the whole freaking system in the trash at one time and just blow it all back up."26Phil Williams, "'We're trying to throw the whole freaking system in the trash,' school voucher sponsor says," NewsChannel 5 Nashville, Apr. 15, 2024, https://www.newschannel5.com/news/newschannel-5-investigates/revealed/revealed-were-trying-to-throw-the-whole-freaking-system-in-the-trash-school-voucher-sponsor-says

Last year, in a closed meeting of Christian millionaires, one attendee declared that the goal was to “take down the education system as we know it today.” Michael Farris, the Virginia lawyer who has become a prominent leader of the modern home-schooling movement, told the group, “We’ve got to recognize that we’re swinging for the fences here, that any time you try to take down a giant of this nature, it’s an uphill battle,” according to a recording obtained by the Washington Post.27Emma Brown and Peter Jamison, “The Christian home-schooler who made ‘parental rights’ a GOP rallying cry,” Washington Post, Aug. 29, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/08/29/michael-farris-homeschoolers-parents-rights-ziklag/.

Few backers of universal vouchers say as much in public, but they no longer keep up a pretense that the school choice movement is about finding ways to provide targeted assistance and opportunities for low-income and minority children. But, Southern governors still like to parade out a group of children of color when they sign voucher bills, as did Georgia Governor Brian Kemp when he held his signing ceremony for the ESA law.28Ty Tagami, “Kemp signs voucher bill he championed,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Apr. 24, 2024. Most voucher proponents and wealthy donors who have coalesced for decades, spending enormous energy and money to advance public financing of private education, have confessed openly to a variety of other motives.

This diverse coalition seeks state-supported Christian education, free-market competition, elite-only schooling, unfettered parental control of education, and regulation-free schools, among other objectives. Their movement has progressed over the decades through the collective organizational work and political action committees bankrolled by the super-rich and corporate leaders who believe that the government is too large, taxes too much, and has little or no business in providing education.29David Montgomery, “School Voucher Proponents Spend Big to Overcome Rural Resistance,” Governing, Mar. 28, 2024, https://www.governing.com/finance/school-voucher-proponents-spend-big-to-overcome-rural-resistance; Jimmy Cloutier, “‘School choice’ super PAC targets Texas GOP incumbents,” Open Secrets, Mar. 4, 2024, https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2024/03/school-choice-super-pac-targets-texas-gop-incumbents/; Katie Meyer, “Jeff Yass, the richest man in Pa., is single handedly keeping school choice PACs flush,” WHYY, May 12, 2021, https://www.phillytrib.com/jeff-yass-the-richest-man-in-pa-is-single-handedly-keeping-school-choice-pacs-flush/article_ee7dde98-1989-5ef1-925c-06473429466c.html; James Holmann with Breanne Deppisch and Joanie Greve, “Koch network laying groundwork to fundamentally transform America’s education system,” Washington Post, Jan. 20, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/paloma/daily-202/2018/01/30/daily-202-koch-network-laying-groundwork-to-fundamentally-transform-america-s-education-system/5a6feb8530fb041c3c7d74db/.

Consider the voucher advocates who believe in economist Milton Freidman’s vision of public education that is entirely based on the government’s providing a voucher to all families with school-age children to go to any school of their choosing. Friedman laid out his free-market idea for voucher-schooling in 1955, a year after Brown. To realize Friedman’s vision today, his adherents’ goal is not a dual school system, but a unitary system of only ESA vouchers. In other words, they seek to destroy public education as it exists.

These free-market proponents fail to grapple deeply with the same issues that Friedman blithely dismissed when condemning “government schools.” In 1955, he acknowledged that his voucher proposal had already been “suggested in several states as a means of evading the Supreme Court ruling against segregation." Friedman’s solution was simple: vouchers paid by government funds would create a system of "exclusively white schools, exclusively colored schools, and mixed schools. Parents can choose which to send their children to." Friedman also opposed a federal fair employment commission to bar racial discrimination in private employment and later the 1964 Civil Rights Act—since it involved government regulation of private businesses for the purpose of prohibiting racial discrimination.30See Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement.”

The belief in the unqualified virtue of private choice means that by design school choice should trump any role government has to prohibit discrimination based on race, sex, and religion in providing the nation’s children with an education. It means the destruction of public schools and their core democratic values.

The emergence of universal vouchers has convinced Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Cara Fitzpatrick to write in The Death of Public Education (2023) that the aim of the movement is to “radically redefine public education in America” with consequences that most citizens have not begun to fully consider.31Cara Fitzpatrick, The Death of Public Education: How Conservatives Won the War over Education in America (New York: Basic Books, 2023). In their revised preface to A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door (2023), Jack Schneider and Jennifer C. Berkshire write that there is now “a very real threat to public education in the United States . . . we’ve seen more destruction than we imagined could be done in a decade. And we’re worried when we next sit down to update this book, we’ll be writing a eulogy rather than a polemic."32Jack Schneider and Jennifer C. Berkshire, A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School (New York: The New Press, 2023).

The Bizarre Disparities in Governing the Emerging Dual School Systems

Ending public schools may be the clear goal of the primary advocates behind the private choice movement, but what is emerging in states that are on their way to adopting universal ESAs is a dual school system with vastly, differing, unequal ground rules, responsibilities, and oversight for educating children with public funds.

Most ESA legislation requires minimal regulations of private schools. Children may be rejected by a private school receiving state vouchers for any number of reasons, spoken or unspoken, relating to income, religion, race, ethnicity, dress, sex, gender identity, or disability. The schools will have the ultimate choice—not the children and their families. State legislation usually prohibits discrimination based on race and national origin, but as with most ESAs, there are no mechanisms for oversight, reporting, investigation of complaints, or enforcement.33Kevin G. Welner & Preston C. Green, “Vouchers as a Mechanism for State-Sanctioned Private Discrimination,” in The School Voucher Illusion: Exposing the Pretense of Equity, eds., Kevin Welner, Gary Orfield and Luis A. Huerta (New York: Teacher College Press, 2023), 87–109; Chase M. Billingham and Matthew O. Hunt, “School Racial Composition and Parental Choice: New Evidence on the Preferences of White Parents in the United States,” Sociology of Education, 89, 2 (2016): 99–117, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040716635718.

The standards for educating children and methods of accountability are minimal or illusory in voucher-supported private schools. The bills establishing ESAs allow these schools to be accredited by a range of private associations, usually comprised of representatives of the schools they accredit. In most southern states, private schools receiving vouchers are not required to assess students for achievement, or, they can use a nationally normed test of their preference, which undermines comparisons among schools. In any case, the results are not always available to the public. Most of these states do not specify, regulate, or review a private school’s curriculum before or after providing voucher funding.

This near-complete freedom to instruct children in whatever way the voucher-supported private schools choose is often justified on the basis that such schools provide students a better education than public schools. There is no factual grounding for this assumption.34Christopher Lubienski, T. Jameson Brewer, and Joel R. Malin, “Bait and Switch: How Voucher Advocates Shift Policy Objectives,” The School Voucher Illusion, 127–141; John Schaaf, “School vouchers hurting students’ academic performance, several studies show,” Kentucky Lantern, Feb. 19, 2024; also, Public Funds, Public Schools has complied a long list of the studies on how private voucher-supported schools have had chronic achievement problems, https://pfps.org/research/. Some private schools are renowned for their high-quality education, but academic study after study has proven this supposition is false. Voucher students are academically harmed on average, particularly in math. Yet, as Cara Fitzpatrick has observed “what the research shows no longer matters.” Private schools are free to indoctrinate students as much as educate them, so long as their parents tolerate or endorse it.35Fitzpatrick, 13.

Some voucher-supported private schools instruct students exclusively about a biblical story of creation. Some require students to pledge allegiance to religious flags and to memorize and recite school-chosen Bible verses. Some teach that homosexuality is a sin. Some expel LGBTQ+ students or even those who associate with LGBTQ+ people. Some use textbooks that belittle the significance of slavery and ignore or downplay the role of Black leaders and the civil rights movement.36Adam Laats, “The Right-Wing Textbooks Shaping What Many Americans Know About History," Time, Oct. 12, 2023, https://time.com/6316978/conservative-textbooks/; Jenna Scaramanga and Michael J. Reiss, “Evolutionary stasis: creationism, evolution and climate change in the Accelerated Christian Education curriculum,” Cultural Studies of Science Education 18 (2023): 809–827. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11422-023-10187-; Jenna Scaramanga and Michael J. Reiss, “Accelerated Christian Education: a case study of the use of race in voucher-funded private Christian schools,” Curriculum Studies 50, no. 1 (Nov. 2017): 1–19, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321373088_Accelerated_Christian_Education_a_case_study_of_the_use_of_race_in_voucher-funded_private_Christian_schools; Adam Laats, Forging a Fundamentalist ‘‘'One Best System’': Struggles Over Curriculum and Educational Philosophy for Christian Day Schools, 1970–1989," History of Education Quarterly 49, no. 1 (Jan. 2010): 55–83; Zack Kopplin, “Hundreds of Voucher Schools Teach Creationism in Science Classes,” PBS News, Jan. 29, 2013; “The Loch Ness Monster Is Real; The KKK Is Good: The Shocking Content of Publicly Paid for Christian School Textbooks," Alternet, June 19, 2012; Steve Suitts, Race and Ethnicity in a New Era of Public Funding of Private Schools: Private School Enrollment in the South and the Nation, Southern Education Foundation, 2015, Appendix 14 (available on request); Julie F. Mead and Suzanne E. Eckes, How School Privatization Opens the Door for Discrimination, National Education Policy Center, Nov. 2018; Steve Suitts, Georgia’s Tax Dollars Help Finance Private Schools with Severe Anti-Gay Policies, Practices, & Teachings, Southern Education Foundation, Jan. 2013. There is nothing in the ESA laws, enacted or pending, that restricts a private school teacher, or home-schooling parent from engaging in a lesson plan of indoctrination on the inherent superiority of the white race, the heroism of John Wilkes Booth and James Earl Ray, the need to exterminate LGBTQ+ people, or to punish any woman who seeks an abortion.

In contrast, southern legislatures have piled up decades of regulations, assessments, reporting requirements, and penalties for traditional public schools and more recently are micro-managing what and how teachers can teach and what books local school libraries can keep on their shelves. From 2008 through 2022, the eleven southern states enacted a total of 3,552 laws regulating their public schools. There are nearly a thousand pages devoted to student discipline.37Compilations developed at Education Legislation/Bill Tracking, National Conference of State Legislatures, https://www.ncsl.org/education/education-legislation-bill-tracking; Compendium of School Discipline Laws and Regulations for the 50 States, Washington, DC and the US Territories, National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, 2023, https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/school-discipline-compendium.

Southern state legislatures have moved to prohibit what they consider to be inappropriate curricula, lesson plans, and books involving diversity, inclusion, and equity—primarily about how and when persons and groups who are not white or heterosexual should be portrayed in the classroom and in library books. Every southern state has passed laws restricting discussions of race and/or gender identity. Most, like Alabama’s recent law, include restrictions for K–12 public schools on “divisive topics,” or like Arkansas, prohibit “indoctrination or critical race theory." No other area of the US has been as aggressive in restricting public school teachers and librarians, who face penalties or dismissal if they fail to adhere to the regulations banning what they can say and what books students may read.38Hannah Natanson, Lauren Tierney and Clara Ence Morse, “Which states are restricting, or requiring, lessons on race, sex and gender,” Washington Post, Apr. 4, 2024; “America’s Censored Classrooms,” PEN America, Aug. 17, 2022, https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms/.

It is hard to imagine a more divergent, unequal arrangement. The state-supported private schools can expel a student or teacher for almost any reason, and their teachers and librarians have complete freedom from governmental interference as to what subjects they teach and how they teach it. They have complete freedom to indoctrinate students—with no consequences.

As Vouchers Spread, Brown’s Promise Dies

During the last seventy years, the nation’s public schools have struggled in meeting the promise of Brown, despite clear proof that racially integrated, well-funded schools improve outcomes for Black children.39Rucker C. Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works (New York: Basic Books, 2019). This promise has been especially important to the South, where the states’ first education laws prohibited Black persons from being taught to read or write; where racially segregated schools offered children of color an inferior education across more than a half century. Due to stubborn, racially defined housing patterns, increasing class disparities, adverse, even hostile Supreme Court decisions, a lack of local, interracial community support, and, as recent research confirms, the growth of school choice, public schools continue to face far too many hurdles in providing all children with a good education.40Gary Orfield and Ryan Pfleger, The Unfinished Battle for Integration in a Multiracial America—from Brown to Now, The Civil Rights Project, UCLA, April 2024. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/the-unfinished-battle-for-integration-in-a-multiracial-america-2013-from-brown-to-now/National-Segregation-041624-CORRECTED-for.pdf. Also, see Tomas Monarrez, Brian Kisida, and Matthew Chingos, When Is a School Segregated? Making Sense of Segregation 65 Years after Brown v. Board of Education, Urban Institute, Sep. 2019. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/when-school-segregated-making-sense-segregation-65-years-after-brown-v-board-education; Laura Meckler, “The unexpected explanation for why school segregation spiked,” Washington Post, May 6, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2024/05/06/school-segregation-study-policies-court-orders/.

The South’s new dual school system renounces and annuls the mandates and hopes of Brown v. Board of Education. As universal vouchers spread, Brown’s promise dies. By their design, vouchers are an abandonment of Brown’s goal of equality of educational opportunity.

Reestablishing a dual school system will damage the prospects of a good education for all who attend public schools—not just low-income and minority children. The southern states were not able to finance two separate school systems during the era of segregation, even though Black students received a pittance of funding. Today that inability remains. The South continues to be far behind the rest of the nation in state and local funding of public schools. The new schemes of universal Education Savings Account vouchers will exacerbate the lack of sufficient funds for all except those higher-income families whose school-age children can attend private schools or home-schools and enjoy the enhancements and enriching experience that vouchers will subsidize.

Parents, grandparents, and others who support public schools and the democratic promise of public education must raise our voices against this reactionary movement and in furtherance of the importance of public schools. Like democracy itself, public schools may be the worst system for delivering all children an equal opportunity for a good education—except for all the others. We must not betray or abandon public education if we are committed to the democratic goal of a more perfect union and a good society for all.

About the Author

An adjunct with Emory University's Institute for the Liberal Arts, Steve Suitts is the author of A War of Sections: How Deep South Political Suppression Shaped Voting Rights in America (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2024). Earlier in his career, Suitts served as the executive director of the Southern Regional Council, vice president of the Southern Education Foundation, and executive producer and writer of "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," a thirteen-hour public radio series that received a Peabody Award for its history of the civil rights movement in five Deep South cities.

Cover Image Attribution:

"Let There Be Light," New Orleans, Louisiana, May 17, 2022. Photograph by J.D. Urban, https://jdurban.com/.Recommended Resources

Text

Black, Derrek W. Schoolhouse Burning: Public Education and the Assault on American Democracy. New York: Public Affairs/Hachette, 2020.

Fitzpatrick, Cara. The Death of Public Education: How Conservatives Won the War over Education in America. New York: Basic Books, 2023.

Ravitch, Diane. Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America's Public Schools. New York: Vintage, 2014.

Schneider Jack and Jennifer C. Berkshire. A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School. New York: The New Press, 2023.

Suitts, Steve. Overturning Brown: The Segregationist Legacy of the Modern School Choice Movement. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2020.

Welner, Kevin, Gary Orfield, and Luis A. Huerta, eds. The School Voucher Illusion: Exposing the Pretense of Equity. New York: Teacher College Press, 2023.

Web

Prokop, Andrew. “The conservative push for “school choice” has had its most successful year ever,” Vox. Sep 11, 2023. https://www.vox.com/politics/23689496/school-choice-education-savings-accounts-american-federation-children.

Public Schools First NC. NC School Vouchers: Using Tax Dollars to Discriminate Against Students & Families. January 2024. https://publicschoolsfirstnc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/NC-Voucher-Schools-Discrimination-Report-2023-Final.pdf.

Save Our Schools Arizona Network. The Impacts of Universal ESA Vouchers: Arizona’s Cautionary Tale. Nov. 2023. https://www.sosaznetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Impacts-of-Universal-Vouchers-Report.pdf.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Steve Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement,” Southern Spaces, June 4, 2019, https://southernspaces.org/2019/segregationists-libertarians-and-modern-school-choice-movement. Available in book form as Overturning Brown: The Segregationist Legacy of the Modern School Choice Movement (Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020). |

|---|---|

| 2. | The best source for the current status and terms of voucher and ESA legislation, including those bills passed and pending in 2023–2024, can be found at FutureEd, an independent think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. https://www.future-ed.org/legislative-tracker-2024-state-private-school-choice-bills/; Seanna Adcox, “‘Universal’ school choice approved in SC House before pilot even begins,” South Carolina Daily Gazette, Mar. 21, 2024, https://scdailygazette.com/2024/03/21/universal-school-choice-approved-in-sc-house-before-pilot-even-begins/; Greg LaRose, “Lawmakers advance education savings accounts, parents’ curriculum choice,” Louisiana Illuminator, Mar. 20, 2024, https://lailluminator.com/2024/03/20/education-savings-accounts/; Greg LaRose, “High price tag for education savings accounts leads to proposal overhaul,” Louisiana Illuminator, May 2, 2024, https://lailluminator.com/2024/05/02/education-savings-account/. |

| 3. | Sam Stockard and Adam Friedman, “Tennessee’s statewide school voucher bill dead, but not forgotten,” Tennessee Outlook, Apr. 22, 2024, https://tennesseelookout.com/2024/04/22/tennessees-statewide-school-voucher-bill-dead-but-not-forgotten/. Karen Brooks Harper, “School voucher supporters bask in primary wins, say goals are within reach,” Texas Tribune, Mar. 6, 2024, https://www.texastribune.org/2024/03/06/texas-primaries-vouchers-school-choice/; Renzo Downey, “Gov. Greg Abbott says Texas is two House votes away from passing school vouchers,” Texas Tribune, Mar. 20, 2024, https://www.texastribune.org/2024/03/20/greg-abbott-tppf-vouchers-primary-runoff/. In identifying ESAs, this essay does not distinguish between those funded by state appropriations and those funded by state tax credits. |

| 4. | Joe Landcaster, “Virginia Is Considering 4 Different School Choice Bills,” Reason, Jan. 22, 2023, https://reason.com/2023/01/22/virginia-is-considering-4-different-school-choice-bills/; Megan Pauly, “Wealthiest Virginians are benefiting most from contributions to school voucher program,” VPM News, July 11, 2022, https://www.vpm.org/news/2022-07-11/wealthiest-virginians-are-benefiting-most-from-contributions-to-school-voucher/. |

| 5. | Suitts, Overturning Brown, 29–32; Bracey Harris, “Reckoning with Mississippi’s ‘segregation academies’,” The Hechinger Report, Nov. 29, 2019, https://hechingerreport.org/reckoning-with-mississippis-segregation-academies/; Russ Latino, “New Legislation Would Create Universal School Choice Program in Mississippi by 2029,” Magnolia Tribune, Feb. 20, 2024, https://magnoliatribune.com/2024/02/20/new-legislation-would-create-universal-school-choice-program-in-mississippi-by-2029/; Bobby Harrison, “House advances bill that would establish close study of universal school vouchers,” Mississippi Today, Mar. 5, 2024, https://mississippitoday.org/2024/03/05/house-committee-universal-vouchers/; Bobby Harrison, “Bill increasing tax credits for private schools defeated at end of session,” Mississippi Today, May 7, 2024, https://mississippitoday.org/2024/05/07/private-schools-tax-credits-mississippi-legislature/. |

| 6. | For the bills terms, see FutureEd, https://www.future-ed.org/legislative-tracker-2024-state-private-school-choice-bills/; Amelia Ferrell Knisely, “Public schools likely to lose $21M after thousands of students left for Hope Scholarship,” West Virginia Watch, Dec. 13, 2023, https://westvirginiawatch.com/2023/12/13/public-schools-likely-to-lose-21m-after-thousands-of-students-left-for-hope-scholarship/; Annelise Hanshaw, “Opposition remains for sprawling education bill expanding Missouri private school tax credits,” Missouri Independent, Mar. 28, 2024, https://missouriindependent.com/2024/03/28/opposition-remains-for-sprawling-education-bill-expanding-missouri-private-school-tax-credits/; McKenna Horsley, “‘Game changer:’ Amendment for public dollars to nonpublic schools clears General Assembly,” Kentucky Lantern, Mar. 15, 2024, https://kentuckylantern.com/2024/03/15/game-changer-amendment-for-public-dollars-to-nonpublic-schools-clears-general-assembly/. |

| 7. | Beth Lewis and Karen Kirsch, “One year in, Arizona’s universal school vouchers are a cautionary tale for the rest of the nation,” AZMirror, Dec. 11, 2023, https://azmirror.com/2023/12/11/one-year-in-arizonas-universal-school-vouchers-are-a-cautionary-tale-for-the-rest-of-the-nation/; Casey Smith, “Indiana’s ‘school choice’ voucher program grew 20% last year—with more growth coming” Indiana Capital Chronicle, June 14, 2023, https://indianacapitalchronicle.com/2023/06/14/indianas-school-choice-program-grew-20-percent-last-year-with-more-growth-coming/. |

| 8. | Author’s calculations based on the bills’ terms and each state’s median income; FutureEd. Also see Jay Waagmeester, “County-by-county distribution of education savings accounts released,” Iowa Capital Dispatch, Aug. 8, 2023. |

| 9. | Suitts, Overturning Brown, 18–53, 87–89; Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement,”; Pauli Murray, States' Laws on Race and Color (Cincinnati, OH: Women's Division of Christian Service of the Methodist Church, 1951). Indiana had school segregation laws from 1869 until 1949, when five years before the Brown decision the legislature revoked the laws, See Murray, 145–147. The eighteen states are the eleven states of the South: West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma in the Border South; Kansas, Indiana, Arizona, and Wyoming. |

| 10. | Suitts, Overturning Brown, 3; EdChoice, The ABCs of School Choice, 2024, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2024-ABCs-of-School-Choice.pdf; author's computations based on the provisions of enacted and pending bills, fiscal notes accompanying legislation and independent estimates by non-profits in the southern states. |

| 11. | Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement.” |

| 12. | David Nevin and Robert E. Bills, The Schools that Fear Built: Segregationist Academies in the South (Washington, DC: Acropolis Books, 1976), 11. |

| 13. | Private school enrollment retrieved and computed from National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), accessed at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pss/privateschoolsearch/. Public school enrollment taken from NCES’ Table 203.70 of 2023 Digest of Education Statistics, accessed at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2023menu_tables.asp. |

| 14. | Jacob Fabina, Erik L. Hernandez, and Kevin McElrath, “School Enrollment in the United States: 2021,” American Community Survey Reports, US Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2023; Bruce D. Baker, Danielle Farrie, David Sciarra, Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card, 2012, 2014, 2017, “Coverage” appendices; R.J Murnane and Sean Reardon, “Long-Term Trends in Private School Enrollments by Family Income,” AERA Open 4, no. 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858417751355. The Murname and Reardon study measured the Census South. |

| 15. | Steve Suitts, A New Majority: Low Income Students in the South’s Public Schools, Southern Education Foundation, 2008, https://southerneducation.org/publications/newmajority/; Steve Suitts, A New Majority Update: Low Income Students in the South and Nation, Southern Education Foundation, 2013, https://southerneducation.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/new-majority-update-bulletin.pdf; computations from Tables 102.40, 204.10, 204.20, 204.70, 204.75d, “Digest of Education Statistics, 2022,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/2022menu_tables.asp. |

| 16. | Mark Lieberman, “Most Students Getting New School Choice Funds Aren’t Ditching Public Schools," Education Week, Oct. 4, 2023, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/most-students-getting-new-school-choice-funds-arent-ditching-public-schools/2023/10. |

| 17. | Arkansas Department of Education, LEARNS, Education Freedom Account Annual Report, 2023–2024, https://arktimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/EFA-Transparency-Report37.pdf; “Iowa’s Students First Education Savings Account program generates more than 29,000 applications,” press of Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds, July 6, 2023, https://governor.iowa.gov/press-release/2023-07-06/iowas-students-first-education-savings-account-program-generates-more; Robin Opsahl, “More than 29,000 apply for Iowa private-school funds in first year,” Iowa Capital Dispatch, July 6, 2023, https://iowacapitaldispatch.com/2023/07/06/more-than-29000-apply-for-iowa-private-school-funds-in-first-year; Ethan Dewitt, “Most education freedom account recipients not leaving public schools, department says,” New Hampshire Bulletin, Mar. 22, 2022, https://newhampshirebulletin.com/briefs/mosteducation-freedom-account-recipients-not-leaving-public-schools-department-says/; News Service Florida, “New report shows nearly 123,000 new students received Florida school vouchers in 2023,” NBC 6 South Florida, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/new-report-shows-nearly-123000-new-students-received-florida-school-vouchers-in-2023/3112869; Florida Department of Education (2023). "Florida’s Private Schools 2022–23: School Year Annual Report," https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/7562/urlt/PS-annualReport2023.pdf; Alec MacGillis, “Private Schools, Public Money: School Leaders Are Pushing Parents to Exploit Voucher Programs,” ProPublica, Jan. 21, 2024, https://www.propublica.org/article/private-schools-vouchers-parents-ohio-public-funds. |

| 18. | Stephne Dyer, “Ohio's Disastrous Voucher Explosion,” Tenth Period, Nov. 29, 2023, https://10thperiod.substack.com/p/ohios-disastrous-voucher-explosion?subscribe_prompt=free; Jennifer Jennings, “Arizona’s school vouchers are helping the wealthy and are widening educational opportunity gaps,” Arizona Mirror, Jan. 12, 2024, https://azmirror.com/2024/01/12/arizonas-school-vouchers-are-helping-the-wealthy-and-are-widening-educational-opportunity-gaps; “Transparency in Scholarship Programs,” Step Up for Students via Florida Phoenix Sep. 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yyl80Jbs9mU6GlV1ktA6zZg8GUjLnsP4/view. The Arizona Common Sense Institute argues that its zip code analysis shows that the state’s ESAs are assisting mostly middle-class families but their analysis lumps together zip codes with median household incomes with those more than twice the state median. In Florida, Step Up for Students expanded the grouping of voucher recipients—the lowest income category showing recipients’ income as high as 185 percent of poverty. Glenn Farley and Kamryn Brunner, Universal ESA’s: Where We Are and Where We Are Going, Arizona Common Sense Institute, May 2023, https://commonsenseinstituteaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CSI-Report-_Universal-ESAs_May-2023-2.pdf; Glenn Farley, Growth and Change: How One Year of Universal Empowerment Scholarship Accounts Has (and Has Not) Altered Arizona’s K–12 Landscape, Arizona Common Sense Institute, April 2024, https://commonsenseinstituteaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CSI_REPORT_ESA_GROWTH_APRIL_2024.pdf. |

| 19. | Carl Davis, Tax Avoidance Continues to Fuel School Privatization Efforts, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Mar. 3, 2023, https://itep.org/tax-avoidance-fuels-school-vouchers-privatization-efforts/; author’s computations from annual Qualified Education Expense Credit Report, Georgia Department of Revenue, 2013–2021, https://dor.georgia.gov/calendar-year-qualified-education-expense-credit-report; Steve Suitts and Katherine Dunn, A Failed Experiment: Georgia's Tax Credit Scholarships for Private Schools (Summary Report), Southern Education Foundation, 2008, https://southerneducation.org/publications/a-failed-experiment; Nancy Badertscher, “Group targets tax credit scholarships - Revenue Department asked to stem students from private schools,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 22, 2011, B-2; Steve Suitts, “Program encourages deception and helps those who don't need it,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 5, 2011, A-13. |

| 20. | Calculations based data on average private tuition prices by state and other costs reported at Raise Right website, https://www.raiseright.com/blog/how-much-do-private-schools-cost, and Prosperity for America website, https://www.prosperityforamerica.org/average-private-school-tuition/. Data on state revenue for state per pupil revenue is found at “2021 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data, US Census. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/school-finances/secondary-education-finance.html. |

| 21. | Steve Suitts, “The South: America’s Legacy of Gross Disparities in Funding Education,” No Time to Lose: Why America Needs an Education Amendment to the Constitution, Southern Education Foundation, 2009, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED524094.pdf. |

| 22. | Bruce D. Baker, Matthew Di Carlo, and Mark Weber, The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems, Jan. 2024, https://www.schoolfinancedata.org/the-adequacy-and-fairness-of-state-school-finance-systems-2024/. |

| 23. | Joanna LeFebvre and Sonali Master, Expiration of Federal K–12 Emergency Funds Could Pose Challenges for States, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Feb. 2024, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/2-28-24sfp.pdf. |

| 24. | “Expanding School Choice: Education Savings Accounts Raise Cost, Accountability Concerns,” Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana, https://parlouisiana.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/PAR-Commentary-Expanding-School-Choice-1.pdf. |

| 25. | “Here’s Why Some States Are Facing a Steeper ESSER Funding Cliff in 2024,” ERS, Mar. 2023, https://www.erstrategies.org/tap/analysis-esser-funds-fiscal-cliff-by-state/#factor3. |

| 26. | Phil Williams, "'We're trying to throw the whole freaking system in the trash,' school voucher sponsor says," NewsChannel 5 Nashville, Apr. 15, 2024, https://www.newschannel5.com/news/newschannel-5-investigates/revealed/revealed-were-trying-to-throw-the-whole-freaking-system-in-the-trash-school-voucher-sponsor-says |

| 27. | Emma Brown and Peter Jamison, “The Christian home-schooler who made ‘parental rights’ a GOP rallying cry,” Washington Post, Aug. 29, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/08/29/michael-farris-homeschoolers-parents-rights-ziklag/. |

| 28. | Ty Tagami, “Kemp signs voucher bill he championed,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Apr. 24, 2024. |

| 29. | David Montgomery, “School Voucher Proponents Spend Big to Overcome Rural Resistance,” Governing, Mar. 28, 2024, https://www.governing.com/finance/school-voucher-proponents-spend-big-to-overcome-rural-resistance; Jimmy Cloutier, “‘School choice’ super PAC targets Texas GOP incumbents,” Open Secrets, Mar. 4, 2024, https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2024/03/school-choice-super-pac-targets-texas-gop-incumbents/; Katie Meyer, “Jeff Yass, the richest man in Pa., is single handedly keeping school choice PACs flush,” WHYY, May 12, 2021, https://www.phillytrib.com/jeff-yass-the-richest-man-in-pa-is-single-handedly-keeping-school-choice-pacs-flush/article_ee7dde98-1989-5ef1-925c-06473429466c.html; James Holmann with Breanne Deppisch and Joanie Greve, “Koch network laying groundwork to fundamentally transform America’s education system,” Washington Post, Jan. 20, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/paloma/daily-202/2018/01/30/daily-202-koch-network-laying-groundwork-to-fundamentally-transform-america-s-education-system/5a6feb8530fb041c3c7d74db/. |

| 30. | See Suitts, “Segregationists, Libertarians, and the Modern 'School Choice' Movement.” |

| 31. | Cara Fitzpatrick, The Death of Public Education: How Conservatives Won the War over Education in America (New York: Basic Books, 2023). |

| 32. | Jack Schneider and Jennifer C. Berkshire, A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School (New York: The New Press, 2023). |

| 33. | Kevin G. Welner & Preston C. Green, “Vouchers as a Mechanism for State-Sanctioned Private Discrimination,” in The School Voucher Illusion: Exposing the Pretense of Equity, eds., Kevin Welner, Gary Orfield and Luis A. Huerta (New York: Teacher College Press, 2023), 87–109; Chase M. Billingham and Matthew O. Hunt, “School Racial Composition and Parental Choice: New Evidence on the Preferences of White Parents in the United States,” Sociology of Education, 89, 2 (2016): 99–117, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040716635718. |

| 34. | Christopher Lubienski, T. Jameson Brewer, and Joel R. Malin, “Bait and Switch: How Voucher Advocates Shift Policy Objectives,” The School Voucher Illusion, 127–141; John Schaaf, “School vouchers hurting students’ academic performance, several studies show,” Kentucky Lantern, Feb. 19, 2024; also, Public Funds, Public Schools has complied a long list of the studies on how private voucher-supported schools have had chronic achievement problems, https://pfps.org/research/. |

| 35. | Fitzpatrick, 13. |

| 36. | Adam Laats, “The Right-Wing Textbooks Shaping What Many Americans Know About History," Time, Oct. 12, 2023, https://time.com/6316978/conservative-textbooks/; Jenna Scaramanga and Michael J. Reiss, “Evolutionary stasis: creationism, evolution and climate change in the Accelerated Christian Education curriculum,” Cultural Studies of Science Education 18 (2023): 809–827. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11422-023-10187-; Jenna Scaramanga and Michael J. Reiss, “Accelerated Christian Education: a case study of the use of race in voucher-funded private Christian schools,” Curriculum Studies 50, no. 1 (Nov. 2017): 1–19, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321373088_Accelerated_Christian_Education_a_case_study_of_the_use_of_race_in_voucher-funded_private_Christian_schools; Adam Laats, Forging a Fundamentalist ‘‘'One Best System’': Struggles Over Curriculum and Educational Philosophy for Christian Day Schools, 1970–1989," History of Education Quarterly 49, no. 1 (Jan. 2010): 55–83; Zack Kopplin, “Hundreds of Voucher Schools Teach Creationism in Science Classes,” PBS News, Jan. 29, 2013; “The Loch Ness Monster Is Real; The KKK Is Good: The Shocking Content of Publicly Paid for Christian School Textbooks," Alternet, June 19, 2012; Steve Suitts, Race and Ethnicity in a New Era of Public Funding of Private Schools: Private School Enrollment in the South and the Nation, Southern Education Foundation, 2015, Appendix 14 (available on request); Julie F. Mead and Suzanne E. Eckes, How School Privatization Opens the Door for Discrimination, National Education Policy Center, Nov. 2018; Steve Suitts, Georgia’s Tax Dollars Help Finance Private Schools with Severe Anti-Gay Policies, Practices, & Teachings, Southern Education Foundation, Jan. 2013. |

| 37. | Compilations developed at Education Legislation/Bill Tracking, National Conference of State Legislatures, https://www.ncsl.org/education/education-legislation-bill-tracking; Compendium of School Discipline Laws and Regulations for the 50 States, Washington, DC and the US Territories, National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, 2023, https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/school-discipline-compendium. |

| 38. | Hannah Natanson, Lauren Tierney and Clara Ence Morse, “Which states are restricting, or requiring, lessons on race, sex and gender,” Washington Post, Apr. 4, 2024; “America’s Censored Classrooms,” PEN America, Aug. 17, 2022, https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms/. |

| 39. | Rucker C. Johnson, Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works (New York: Basic Books, 2019). |

| 40. | Gary Orfield and Ryan Pfleger, The Unfinished Battle for Integration in a Multiracial America—from Brown to Now, The Civil Rights Project, UCLA, April 2024. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/the-unfinished-battle-for-integration-in-a-multiracial-america-2013-from-brown-to-now/National-Segregation-041624-CORRECTED-for.pdf. Also, see Tomas Monarrez, Brian Kisida, and Matthew Chingos, When Is a School Segregated? Making Sense of Segregation 65 Years after Brown v. Board of Education, Urban Institute, Sep. 2019. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/when-school-segregated-making-sense-segregation-65-years-after-brown-v-board-education; Laura Meckler, “The unexpected explanation for why school segregation spiked,” Washington Post, May 6, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2024/05/06/school-segregation-study-policies-court-orders/. |