Overview

Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society cemeteries, which together constitute the oldest African American burial ground in the Washington, DC area, is a long-contested space with powerful emotional holds on local communities of color. Among the cemetery’s most charged and beloved sites, the locus of frequent material gifts by visitors, and of a recent act of desecration, is the enigmatic headstone of a seven year old girl, "Nannie," who died in 1856. This essay points to historical antecedents of the gift-giving practice, considers the identity of a child long subject to speculation, and insists on the importance of such sites for movements of social justice.

During the night of June 19, 2023, the first federally recognized Juneteenth holiday, an unknown vandal or vandals desecrated by fire a much-beloved child's mid-nineteenth-century headstone in Washington, DC's oldest African American burial ground, the Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society cemetery in Georgetown. For a quarter century, visitors to the grave marker have left objects—dolls, toys, and birthday cards—a practice that harkens to the nineteenth century history of the cemetery. Why has this particular child's memorial become the scene of gift-giving? And why did it become a site of apparent racist attack? Equally puzzling is the identity of the child. The simple, crowned bluestone marker bears the following inscription:

Nannie

Born May 26, 1848

Died May 18, 1856

The identity of "Nannie" has been a mystery for generations. Her short life spanned momentous events in local and national African American history. She was born one month after the ill-fated mass escape of enslaved people on the schooner The Pearl, the largest attempted self-liberation event in antebellum US history. She was two years old in 1850 when the slave trade (although not slavery) within the District of Columbia was banned and the Fugitive Slave Act made life precarious for free people of color within the District. She was four when Uncle Tom's Cabin was published, six when fugitive slave Anthony Burns was arrested in Boston and shipped back to Virginia, enraging abolitionists during the same year the Republican Party was founded. Nannie was seven when open mass violent conflict erupted in Kansas. In the month of her death, the US Supreme Court called for re-argument of Dred Scott v. Sanford, leading to the majority opinion in March 1857, authored by Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, holding that persons of African descent "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

This essay places Nannie's enigmatic gravesite and headstone in the context of the social, political, and spiritual history of the cemetery. We then propose an identity for the girl commemorated as "Nannie," who died one week shy of her eighth birthday, and consider why her resting place has become a compelling site of emotional connection, commemoration, and resistance. Finally, we speculate as to why persons unknown, on the night of Juneteenth, sought to attack this particular site.

The Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Cemetery

Many District of Columbia residents have incorrectly assumed that Mount Zion Cemetery is composed of a single burial ground. A three-acre property, it actually consists of two separate but adjacent cemeteries of equal size: the old Methodist Burying Ground (now known as Mount Zion Cemetery), and the Female Union Band Society Cemetery.1Stanton L. Wormley, ed. Mt. Zion Cemetery: Washington, DC, Brief History and Interments, comp. by Paul E. Sluby, Sr. (Washington DC: Columbian Harmony Society, 1984); Paul E. Sluby, Sr., Bury me deep: Burial Places Past and Present in and Nearby Washington, D.C.: A Historical Review and Reference Manual (Temple Hills, MD: P.E. Sluby, 2009). In 1931, the Federal Government took one half acre of the earlier cemetery grounds to create Rock Creek Parkway and an adjacent horse riding trail. The grounds are now under the authority of the National Park Service.

The old Methodist Burying Ground was purchased in 1808 by the Montgomery Street Church in Georgetown, one of the first Methodist churches in the country, founded in 1772 (known today as the Dumbarton United Methodist Church).2The church was formerly located on Twenty-Eighth Street between M and Olive Streets, N.W. (formerly Montgomery Street between Bridge and Olive Streets), approximately one-half mile southwest of the cemetery. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the membership of the Montgomery Street Church was almost 50 percent Black and included free and enslaved congregants. Upset with segregated and racist practices, 125 Black members left Montgomery Street in 1816 and formed the first Black congregation in the District of Columbia, known then as the Meeting House or the Little Ark, and today as Mount Zion United Methodist Church. The two Methodist churches, white and Black, continued to share the Methodist Burying Ground until after the Civil War.3The land was purchased from Thomas Beall, who had inherited extensive property from his grandfather Ninian Beall (1630–1717). In the early nineteenth century, Beall owned about fifteen slaves and many properties in Maryland and the District of Columbia, including the properties now known as Dumbarton House, Beall-Washington House, Conjuror's Disappointment and Rock of Dumbarton. He served in the 1790s as the second Mayor of Georgetown and played an important role in establishing the District of Columbia. On Dumbarton Methodist, see: Jane Donovan, Many Witnesses: A History of Dumbarton United Methodist Church 1772–1990 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton United Methodist Church, 1998); J.W. Cromwell, "The First Negro Churches in the District of Columbia," The Journal of Negro History 7, no. 1 (1922): 64–107; Janet Lee Ricks, "Mt. Zion United Methodist Church Marks 185th Anniversary," Washington History 13, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2001): 71–73.

Around 1832, a group of free women of color formed a benevolent organization, the Female Union Band Society (FUBS). A decade later and for $250, they engaged Joseph T. Mason—schoolteacher and free man of color—to purchase a plot of land adjacent to the Old Methodist Burying Ground to use as a burial ground for the society's members and their families. Court records indicate the land was acquired from Joseph E. Whitehead of New Orleans. Mason ran a school within the Black church that after 1844 was known as Mount Zion Methodist. If Nannie was a free child of color in the vicinity, Joseph Mason most likely taught her as a pupil.

It is also believed that these burial grounds also served as a refuge on the Underground Railroad. Mount Zion Church and the burial holding vault located on the Mount Zion Cemetery property are said to have opperated as hiding site for escaping "passengers" heading north. Over the first half of the nineteenth century, the numbers of enslaved in the District of Columbia declined. By 1850 (when Nannie was two years old) 3,185 of the 13,746 Black inhabitants are listed as enslaved. In DC, enslaved and free persons often lived, worked, and worshipped together, although their life conditions were often precarious.4Pauline Gaksins Mitchell, The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist Church and Mt. Zion Cemetery, 51 (Washington, DC: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1984): 103–18. The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist Church is 51st separately bound book; Stella Mae Richard, "Two Hidden Cemeteries in the Georgetown Section of Washington D.C.," Negro History Bulletin, Washington 32, no. 8 (Nov 1969): 29.

In 1849, Oak Hill Cemetery, reserved for white burials, was established by the financier, philanthropist, and former slaveowner William Wilson Corcoran (1798–1888), later denounced as a Confederate sympathizer, who after the Civil War founded the Corcoran Gallery of Art.5In 1830, Thomas Corcoran, William Wilson Corcoran's father and sometime mayor of Georgetown, owned five enslaved people. The 1840 census indicates that William Wilson Corcoran owned one male enslaved person between the ages of ten and twenty-three and three free women of color, who may have been previously enslaved by him; all resided in his household. In 1845, William Corcoran manumitted the enslaved woman Mary and four of her children. (National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, Records of Manumission, vol. 3, Record Group 60, Washington, DC; cited in Mark Laurence Goldstein, "Capital and Culture: William Wilson Corcoran and the Making of Nineteenth-Century America" (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 2015), 30–31. This woman may appear in the 1850 census as Mary Degges, born 1819, married to Judson Degges, with children Adelia, born 1834 and Mary, born 1837. Corcoran's "Last Will and Testament," September 6, 1887, provides a stipend of $200 to a woman named Mary Neale, "once owned by me, and long since manumitted." This person may be the Mary Neil who evidently married John Neil in 1875, and may have been born as Mary Degges, daughter of the older Mary Degges. This 22.5 acre cemetery sits adjacent to the Female Union Band Society Cemetery and is separated by a sliver of elevated land, Lyon Mill Road, that served as a path leading to a mill within present-day Rock Creek Park. After Oak Hill opened, whites at the Methodist church gradually abandoned the Methodist Burying Ground and began to disinter their white relatives and re-bury them in Oak Hill and other "white only" cemeteries around the city. Early references to the area that became Mount Zion Cemetery are to the "Methodist Episopal Burial Ground of Georgetown," the "Old Methodist Burial Ground," or the "Colored Methodist Burial Ground."6Richard P. Jackson. The Chronicles of Georgetown DC from 1751 to 1878. (Washington DC: R.O. Pokinhorn, Printer, 1878), 270; Wesley E. Pippenger, District of Columbia Interments (Index to Death), January 1, 1858 to July 31, 1874 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 1999), xix. The land in question is north of Q Street and east of Lyons (Mill) Road (now an extension of 27th street) and Oak Hill Cemetery, extending down hilly slopes to Rock Creek. Over time, the eastern section of this burying ground became known as Mount Zion Cemetery (or Mount Zion East) and the western zone as the Female Union Band Society cemetery. By 1879, white parishioners entirely ceased using the Old Methodist Burying Ground and leased it to Mount Zion Church for ninety-nine years, its name officially changing to "Mount Zion Cemetery."

As racist policies and practices pushed many Black residents out of Georgetown over the next half-century, the cemetery suffered neglect and abandonment. The final burial in Mount Zion took place in the early 1950s. The District's department of health condemned the two cemeteries in 1953, prohibiting future burials. In the 1960s, developers sought to buy the land and disinter the remains in both burial grounds. African American activists, including the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation (ABC), energetically resisted these plans, and in the mid-1970s secured court and appellate rulings that safeguarded the cemeteries' futures as a memorial park, with disinterments prohibited. As part of planning and restoration, many headstones and markers in both cemeteries were relocated and consolidated in 1975, evidently with the intention of restoring and returning them to their original positions. However, given the fragility of the stone tablets, they were left in place and not returned.7Before the moving of the stones, Mount Zion stones were mapped with a good deal of detail; the Female Union Band Society mapping was, it appears, less thorough. Richards, Two Hidden Cemeteries, 29; Mitchell, The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist, 103–118; Kathleen Menzie Lesko, Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of its Black Community from the Founding of "The Town of George" in 1751 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016); Steven J. Richardson, The Burial Grounds of Black Washington: 1880–1919 (Washington: DC: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1989), 52: 304–326. Burial Grounds is the 52nd separately bound book.

The cemeteries were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. The joint cemetery is now maintained by the non-profit Black Georgetown Foundation (until recently The Mount Zion–Female Union Band Historic Memorial Park, Inc.) The cemeterties' survival and restoration in the face of powerful white-dominated development interests is celebrated as a miraculous point of deep pride. It is located at the very top of Georgetown, one of the wealthiest and whitest quarters of the city, adjacent to Oak Hill Cemetery, where many of the city's elite white residents have been interred since the mid-nineteenth century. It sits besides Dumbarton House, a structure long associated with prominent white slaveowning families, now the national headquarters of the Colonial Dames of America. It overlooks Rock Creek Park, the greenway that connects the metropolitan area's wealthy northwestern suburbs to the downtown seat of government. The cemetery represents, for many, a defiant unofficial monument to Black struggles for self-determination in a historically Black city undergoing rapid gentrification, still denied statehood and Congressional voting representation.8US District Court Judge Oliver Gasch reversed the order allowing disinterment by developers in order to build condos, stating that such action by the heirs and developers "cannot but offend the sensitivities of civilized people." "Equally important," said the judge, "is the fact that not only would such a degradation be perpetrated against the dead, but in this instance the violation of their graves involves the destruction of a monument to evolving free black culture in the District of Columbia." Female Union Band Ass'n v. Unknown Heirs at Law, 403 F.Supp. 540, 547 D.D.C. 1975.

Gravesite Objects as Memorialization Practices

Since organized efforts began in the 1970s to safeguard and restore Mount Zion, volunteers have often come across bottles, pottery shards, sea shells, and related objects. Frequently dismissed by officials as "debris" or "trash," these objects are interpreted by guardians of the cemetery as traces of much older Black memorialization practices, dating back into the era of enslavement.

Strong evidence for this interpretation is provided by a series of newspaper articles, widely reprinted during August and September 1894, documenting popular memorial practices in Mount Zion cemetery. Local African Americans regularly placed objects associated with the life experiences of the deceased on gravesites, including medicine bottles containing residue of medications taken during final illnesses.9Versions of this story are reprinted in the Gazette (York, Pennsylvania), 10 Aug 1894, 5, The Clarion Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), September 10, 1894 and many other newspapers in August and September 1894. In the articles, Sexton Henry Bowles (c. 1840–1907) explained that familiar toys and tools encouraged the spirits of the dead to "confine their manifestations to the cemetery," rather than haunting the living. On the grave of a "Mr. Johnsing" (perhaps Henry Johnson, who died in December of 1893) his widow placed a wooden hobby horse, "buried up to its haunches," commemorating the dead man's occupation as an express wagon driver, as well as his beloved horse. Each night, she explained, her late husband's spirit would hitch and unhitch the wooden horse, and thus be distracted from tormenting his surviving kin. The half-burial of the horse evoked the object's transitional status, mediating between the realms of the Living and the Dead.

Placed on the grave of a young boy, a high chair and toy wheelbarrow signified objects of importance in his life. A woman named "Lize Lundy," who was fond of wearing a new bonnet to church each Sunday, was honored with her final bonnet and a hand mirror placed on her grave. A particularly complex grave assemblage, perhaps for a military veteran, featured a mound guarded by two large toy soldiers, with smaller soldiers in front of each large soldier; at the mound's center stood three upright bottles. The items may be thought of as "transitional objects," easing the transition from one life stage to another. By repeatedly touching intermediate objects, mourners gradually come to terms with a painful loss and in time relinquish the full burden of their immediate grief.10D.W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock Publications, 1971); Melanie Klein, "Mourning and Its Relation to Manic-Depressive States," The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 21 (1940): 125–153; Ellen Schattschneider, "Buy Me a Bride: Death and Exchange in Northern Japanese Bride-Doll Marriage," American Ethnologist 28, no. 4 (2001): 854–880.

These practices are consistent with vernacular African American grave decorations widely documented throughout the Americas, having African antecedents, and transmitted by enslaved and free people across the generations.11Jamieson, Ross W., "Material Culture and Social Death: African-American Burial Practices," Historical Archaeology 29 (1995): 39–58; John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978). Bottles, shells, pottery and other elements are held to ward off mystical dangers and ease the Dead's transition into the other world and towards ancestral status.12Thompson, Robert Farris, Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy (New York: Random House, 2010); Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, 142; Savannah Unit Georgia Writers' Project Work Administration, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1940).

The Nannie Stone in the Modern Era

Public attention to Nannie's gravesite is largely due to the efforts of Omar "Casey" Ibrahim, born around 1936, who during the summer 1997 worked as a volunteer to clear and help restore the cemetery, much of which had been inaccessible due to fallen limbs and extensive weeds and vines. At an October 1997 ceremony, Ibrahim pointed to Nannie's burial site, which was marked only by a fallen-over slab. He urged each person to adopt a gravesite to care for. "I've adopted Nannie . . . I'm going to set her stone up straight and clean all around there. Then I'll put up a little red fence. And then I'll give her a teddy bear and other toys that children like."13Linda Wheeler, "Black Church Honors it Historic Cemetery," Washington Post, October 14, 1997. Mr. Ibrhaim and his daughter continued to place objects at Nannie's memorial for several years. Inspired by this example visitors across the subsequent years have placed objects, including dolls, ribbons, toys, and birthday cards, in front of the Nannie headstone.14Theresa Vargas, "Someone Keeps Leaving Toys and Birthday Cards at a 7-Year-Old's Grave in a Historic Black Cemetery. No One Knows Who," Washington Post, April 17, 2021. The marker has catalyzed speculation and a series of commemorative art works, including by artist Lindsey Brittain Collin, inspired by dolls left at Nannie's graveside.

Nannie's grave marker is currently located within the old "Female Union Band Society" section, at times referred to as "Mount Zion West." The headstone is propped up against a tree. Like many stones in the cemetery it has been moved at least once. Its original location is not marked on the 1970s' survey, but was well within this section—which means that Nannie was almost certainly a child of color who was part of the substantial free Black population residing in Georgetown and other DC neighborhoods. It is possible, however, that she was enslaved for some or all of her short life. Slavery was legal in the District until April 16, 1862, when an act of Congress instituted a compensated emancipation system.15Mary Mitchell, "'I Held George Washington's Horse': Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia," Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, DC 63/65 (1963–1965): 221–229; Reidy, Joseph P, "The Winding Path to Freedom under the District of Columbia Emancipation Act of April 16, 1862," Washington History 26, no. 2 (2014): 18–22. The complex relationships between enslaved and free persons of color in the antebellum District of Columbia are examined in Mary Corrigan, "A Social Union of Heart and Effort: the African-American Family in the District of Columbia on the Eve of Emancipation" (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 1996). The broader context of DC emancipation is addressed in Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Considering "Nannie"

Who was Nannie, and why was this striking headstone? The inscription is done professionally and with great care, which suggests that it was paid for by someone of means, or with access to a network of supporters who helped fund the purchase.

Why was only the child's first name used, given that surnames are usually inscribed on Mount Zion–FUBS headstones? Possibly because the child was buried within an extant family plot that was obscured through the relocation of markers in the 1975. Or, if Nannie had been fathered by a prosperous white man with a woman of color, outside of wedlock, the father might have paid for a headstone, but been unwilling to authorize his surname.

The name Nannie, like Anne, is derived from the Hebrew term for favor or grace. Nannie was sometimes a diminutive for Ann, Agnes, Nancy, or other girls' names. "Nannie" was also a girl's name in its own right in the mid-nineteenth century. The 1850 census records about seventeen free women of color named "Nannie" living in the United States. The 1870 census, the first to list all African Americans, lists about two-thousand black women named Nannie. An obelisk to Nannie Diggs, who died October 23, 1923, at age sixty-on, was erected by her daughter Katie Anderson in the same section of the cemetery as the headstone to the mysterious child "Nannie." The records of the Mount Zion–FUBS cemetery list two other Nannies: Nannie Diggs, born 1852 in Virginia, and a Nannie Washington, born 1858, also in Virginia. The most prominent Black Washingtonian bearing the name "Nannie" was the pioneering educator and religious leader, Nannie Helen Burroughs, 1879 –1961, born in Virginia, and a member at 19th Street Baptist. Two months before the death of the young "Nannie" buried in Mount Zion, the Evening Star (DC) reported the death of "Old Aunt Nannie," an enslaved woman at the purported age of 112 years near Powhatan Courthouse, Virginia."16Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 6, 1856, 3.

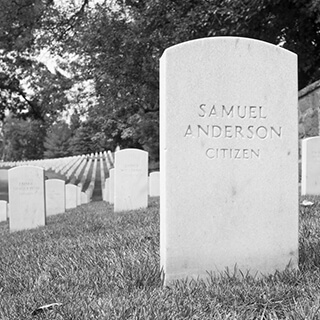

A Candidate for Nannie: William Teney's Child

Official registers of death were kept in the District of Columbia for Black and white burials from 1855 onwards. However, a register of burials of the Joseph F. Birch Funeral Home, was kept from January 1, 1847 for white and Black burials, and is an invaluable historical resource. Children's deaths were listed by the name of the parent (usually the father) followed by the word "child." The Birch's "Register of Burials, Colored Persons" begins with death #1, January 11, 1847, "Colbert's child," buried in the "Colored Methodist Ground" (the cemetery later known as Mt. Zion). Nineteen pages later, under May 1856, the register lists death #368, "Wm Teney child," as interred in the same Colored Methodist Episcopal Burial Ground. The precise date of death is somewhat ambiguous. The previous line, for death #367, is clearly May 11. Then, for William Teney's child, inverted double commas, indicating ditto, are given for the death date, which would seem to indicate May 11, whereas "our" Nannie, according to her headstone, died one week later on May 18. Nonetheless, other aspects of this child align with our search.17Paul E. Sluby and Stanton L. Wormley, eds., Register of Burials of the Joseph F. Birch Funeral Home, Volume I, (Washington, DC: Columbian Harmony Society, January 1, 1847–April 12, 1864). Also available as FamilySearch microfilm #008135478. Note that a reference to "William Tenney child," is not listed in in Pippenger, District of Columbia Interments.

The most reasonable candidate for William Teney strikes us as a free Black man William Tinny, age twenty or thirty, laborer, born in Maryland, listed with his family in the 1850 census. He is married to Bridget Tinny, born Maryland, age twenty-four, with three children: Sarah Tinny, age seven, born in Maryland c. 1843: Mary Tinny, age five, born in the District of Columbia, c. 1845; Francis Tinny, age three, born in the District of Columbia, c. 1847. Of these three children. Francis, who is born around 1847, is not mentioned in the 1860 census or other subsequent records, and is thus a strong candidate for "our" Nannie. Although Nannie was not a standard nickname for Francis in the period, it seems possible that Nannie was a term of endearment used for her within the family, perhaps rhyming with "Frannie."18Francis's father William appears in a November 15, 1827 District of Columbia manumission record:

"Know all men, by these Presents that I Charles Teney of Washington County in the District of of Columbia for divers good causes and considerations, me thereunto moving [?] and also in further consideration of the sum of one dollar to me in hand paid have released from slavery, liberated and manumitted and set free, and by these present do release from slavery, liberated and manumit and set free my slave woman named Matilda Teney aged about thirty five years, and her three children Anne aged about thirteen years, Andrew aged about three years and William Don Otious aged about 19 months, and able to work and gain a sufficient livelihood and maintenance, which said mentioned slaves were obtained by me as heir at law of my son William Don Otious Teney late of said County deceased, and them the said Matilda and her three children, Ann Andrew and William Don Otious I do declare to be henceforth free, manumitted and discharged from all manner of servitude and service to me and my executors, administrators, or assignees forever. In presence of Lemuel J Middleton and A Balmance."

Two other candidates for "Nannie" are suggested by comparing the 1850 and 1860 censuses: (A) The daughter "Ann" (born about 1848) of freed-people Francis Yates and Caroline (Smith) Yates, who later took the surname Cole, does not appear in the records after 1850. Francis and Caroline married three months before the birth of the "Nannie" memorialized on the headstone. Anna Yates, Black, one year old, died 10 August 1857 and was buried in Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal burial ground; she may be related, but is clearly a different person; (B) Ann E. Twine, the daughter of coachman David Twine and his wife Caroline Gray Twine, both free persons of color in the District. David Twine was interred in Mount Zion in 1894. A member of Metropolitan A.M.E., David Twine came from a family with long connections to Georgetown and the local Black Methodist community. Both of these girls appear in the 1850 census but are not enumerated in the 1860 census or other records. However, Ann E. Twine may appear in the 1860 census as "Eliza Twine", ten years old, living with an older couple that may be her grandparents. Neither girl is indicated in the DC Register of Burials, so they seem much less likely candidates than the child of William Tenney, who died in May 1856 and who is recorded as interred in the "Colored Methodist Burial Ground."

Francis Tenney (c.1847–c.1856) was born into a free family of color who had been free in the District of Columbia for at least twenty years prior to her birth, and who had struggled intensively to achieve freedom. As noted in the appendices, her family clearly had an extensive network of free kin in the District of Columbia who in 1856 might have pooled resources to enable to purchase and inscription of the well-made headstone.

Desecration

During midday on Monday, June 19, 2023, the first time Juneteenth had been celebrated as a federal holiday, over two-hundred people gathered in Mount Zion-Female Union Bank Society Cemetery to honor the burial ground and the history of African American liberation. The event, organized by the Black Georgetown Foundation, which oversees the two burial grounds, had been widely advertised on social media and radio. Attendees, many of them first-time visitors to the site, were moved by the story of the struggle to preserve and document the cemeteries and the lives of those interred. The event culminated with a gathering in front of Nannie's headstone, where speakers reflected on the enigmas of her life and the history of antebellum Black Georgetown.

During the night of June 19–20, a person or persons unknown set a fire in front of the Nannie headstone, destroying or damaging toys and objects left as offerings during the previous year and leaving dark burn marks on the stone. The attacker was likely aware of the connection felt by thousands of people to Nannie, the preceding day's events, and the fact that in recent years this marker has, more than any other memorial on the grounds, compelled the greatest number of gifts.

The gravestone desecration and the burning of the objects was a form of racial terror, reminiscent of the burning and bombing of sites of Black assembly and resistance such as churches, and indeed, of the burning of victims of lynching. In the days following the fire, people stopped by the cemetery to give new offerings to Nannie.

Memorialization and #BlackLivesMatter

Why has Nannie's grave marker inspired such an outpouring of offerings and attention by scores of people with no direct kinship link to her? Certainly her young age is compelling, as is the approaching storm of national disunion during the span of her life. Perhaps equally significant are the still-ongoing crises of racism and inclusion in the United States. Her prominent, yet plain marker, is suffused with resonance for past and present injustices. The obscurity of her identity allows Nannie to evoke the "many thousands gone" among persons of color in the District and elsewhere. In the present era of #BlackLivesMatter and the continuous assaults on the rights of persons of color to own their bodies, the story of Mount Zion cemetery, nearly eradicated to serve commercial development interests, is particularly resonant. The restoration of this storied African American burial ground, now surrounded by multiples sites of white, elite privilege, is a powerful testimony to African American resilience and cultural vibrancy.

Nannie, for many, has come to represent hallowed ground and the larger history and geography of racial segregation, anti-Blackness, and liberation struggles within the District of Columbia. The centuries-old African-Atlantic practice of grave decoration, ubiquitous in this cemetery in the nineteenth century, has been revived to honor Nannie's memory—poignant testimony to the power of ancestral remembrance—as well as the continuing mission of activism.

About the Authors:

Mark Auslander is the author of The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011). He is a visiting faculty member in anthropology at Mount Holyoke College.

Lisa Fager, Executive Director of the Black Georgetown Foundation, oversees the Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society cemeteries in Georgetown, Washington DC.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge the tireless work and insights of community historians Mary Belcher and Patrick Tisdale, and the many other volunteers associated with the Mount Zion–Female Union Band Society Cemeteries, and the Mount Zion United Methodist Church in documenting the important history associated with the cemetery and the local faith community. Erika Berg located 1894 newspaper accounts of grave decorations in Mount Zion. We are grateful to Carlton Fletcher, Fath Davis Ruffins, Russell Smith, Ibrahim Sundiata, and Jay Ball for many interpretive insights into this narrative. Many thanks to the staff at the Kiplinger Library, Washington historical Society; The Library of Congress Periodicals and Manuscripts rooms; Special Collections and University Archives, The Maryland Room Hornbake Library, University of Maryland College Park; the Smithsonian Institution Archives; the District of Columbia Public Library Washingtoniana/People’s Archive Division and the Georgetown Library Peabody Room; the District of Columbia Archives; the National Archives and Records Administration; the Maryland State Archives; and the Daughters of the American Revolution Library. Particular thanks to Andrew Boisvert of the DAR Library and Damani Davis and Rose Buchanan of NARA Archives 1 for their insights into antebellum District of Columbia records. Omar “Casey" Ibrahim generously shared his memories of recovering the Nannie memorial stone and initiating the modern gift-giving tradition in the 1990s. We are grateful for careful editorial work on this post by Allen Tullos and the Southern Spaces team.

Appendices

Nannie's Stone: Appendices by Mark Auslander and Lisa Fager

Recommended Resources

Text

Auslander, Mark. The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Galland, China. Love Cemetery: Unburying the Secret History of Slaves. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

Ginsburg, Rebecca. "Freedom and the Slave Landscape." Landscape Journal 26, no. 1 (2007): 36–44.

Jones, Diane. "The City of the Dead? The Place of Cultural Identity and Environmental Sustainability in the African-American Cemetery." Landscape Journal 30, no. 2 (2011): 226–240.

Lesko, Kathleen Menzie, Valerie M. Babb, and Carroll R. Gibbs. Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of "The Town of George" in 1751 to the Present Day. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2022.

Masur, Kate. An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Nunley, Tamika. At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, and Shifting Identities in Washington, D.C. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

Savoy, Lauret. Trace: Memory, History, Race and the American Landscape. New York: Counterpoint Press, 2015.

Web

Dunnevant, Justin, Delende Justinvil, and Chip Colwell. "Craft an African American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act." Nature. May 19, 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01320-4.

Moore, Jack. "Eerie, Beautiful, Forgotten: A Tour of DC's Historic Cemeteries." WTOP News. October 27, 2017. https://wtop.com/local/2017/10/eerie-beautiful-forgotten-tour-dcs-historic-cemeteries-photos/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Stanton L. Wormley, ed. Mt. Zion Cemetery: Washington, DC, Brief History and Interments, comp. by Paul E. Sluby, Sr. (Washington DC: Columbian Harmony Society, 1984); Paul E. Sluby, Sr., Bury me deep: Burial Places Past and Present in and Nearby Washington, D.C.: A Historical Review and Reference Manual (Temple Hills, MD: P.E. Sluby, 2009). In 1931, the Federal Government took one half acre of the earlier cemetery grounds to create Rock Creek Parkway and an adjacent horse riding trail. The grounds are now under the authority of the National Park Service. |

|---|---|

| 2. | The church was formerly located on Twenty-Eighth Street between M and Olive Streets, N.W. (formerly Montgomery Street between Bridge and Olive Streets), approximately one-half mile southwest of the cemetery. |

| 3. | The land was purchased from Thomas Beall, who had inherited extensive property from his grandfather Ninian Beall (1630–1717). In the early nineteenth century, Beall owned about fifteen slaves and many properties in Maryland and the District of Columbia, including the properties now known as Dumbarton House, Beall-Washington House, Conjuror's Disappointment and Rock of Dumbarton. He served in the 1790s as the second Mayor of Georgetown and played an important role in establishing the District of Columbia. On Dumbarton Methodist, see: Jane Donovan, Many Witnesses: A History of Dumbarton United Methodist Church 1772–1990 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton United Methodist Church, 1998); J.W. Cromwell, "The First Negro Churches in the District of Columbia," The Journal of Negro History 7, no. 1 (1922): 64–107; Janet Lee Ricks, "Mt. Zion United Methodist Church Marks 185th Anniversary," Washington History 13, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2001): 71–73. |

| 4. | Pauline Gaksins Mitchell, The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist Church and Mt. Zion Cemetery, 51 (Washington, DC: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1984): 103–18. The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist Church is 51st separately bound book; Stella Mae Richard, "Two Hidden Cemeteries in the Georgetown Section of Washington D.C.," Negro History Bulletin, Washington 32, no. 8 (Nov 1969): 29. |

| 5. | In 1830, Thomas Corcoran, William Wilson Corcoran's father and sometime mayor of Georgetown, owned five enslaved people. The 1840 census indicates that William Wilson Corcoran owned one male enslaved person between the ages of ten and twenty-three and three free women of color, who may have been previously enslaved by him; all resided in his household. In 1845, William Corcoran manumitted the enslaved woman Mary and four of her children. (National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, Records of Manumission, vol. 3, Record Group 60, Washington, DC; cited in Mark Laurence Goldstein, "Capital and Culture: William Wilson Corcoran and the Making of Nineteenth-Century America" (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 2015), 30–31. This woman may appear in the 1850 census as Mary Degges, born 1819, married to Judson Degges, with children Adelia, born 1834 and Mary, born 1837. Corcoran's "Last Will and Testament," September 6, 1887, provides a stipend of $200 to a woman named Mary Neale, "once owned by me, and long since manumitted." This person may be the Mary Neil who evidently married John Neil in 1875, and may have been born as Mary Degges, daughter of the older Mary Degges. |

| 6. | Richard P. Jackson. The Chronicles of Georgetown DC from 1751 to 1878. (Washington DC: R.O. Pokinhorn, Printer, 1878), 270; Wesley E. Pippenger, District of Columbia Interments (Index to Death), January 1, 1858 to July 31, 1874 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 1999), xix. The land in question is north of Q Street and east of Lyons (Mill) Road (now an extension of 27th street) and Oak Hill Cemetery, extending down hilly slopes to Rock Creek. Over time, the eastern section of this burying ground became known as Mount Zion Cemetery (or Mount Zion East) and the western zone as the Female Union Band Society cemetery. |

| 7. | Before the moving of the stones, Mount Zion stones were mapped with a good deal of detail; the Female Union Band Society mapping was, it appears, less thorough. Richards, Two Hidden Cemeteries, 29; Mitchell, The History of Mt. Zion United Methodist, 103–118; Kathleen Menzie Lesko, Valerie Babb, Carroll R. Gibbs, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of its Black Community from the Founding of "The Town of George" in 1751 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016); Steven J. Richardson, The Burial Grounds of Black Washington: 1880–1919 (Washington: DC: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1989), 52: 304–326. Burial Grounds is the 52nd separately bound book. |

| 8. | US District Court Judge Oliver Gasch reversed the order allowing disinterment by developers in order to build condos, stating that such action by the heirs and developers "cannot but offend the sensitivities of civilized people." "Equally important," said the judge, "is the fact that not only would such a degradation be perpetrated against the dead, but in this instance the violation of their graves involves the destruction of a monument to evolving free black culture in the District of Columbia." Female Union Band Ass'n v. Unknown Heirs at Law, 403 F.Supp. 540, 547 D.D.C. 1975. |

| 9. | Versions of this story are reprinted in the Gazette (York, Pennsylvania), 10 Aug 1894, 5, The Clarion Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), September 10, 1894 and many other newspapers in August and September 1894. |

| 10. | D.W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock Publications, 1971); Melanie Klein, "Mourning and Its Relation to Manic-Depressive States," The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 21 (1940): 125–153; Ellen Schattschneider, "Buy Me a Bride: Death and Exchange in Northern Japanese Bride-Doll Marriage," American Ethnologist 28, no. 4 (2001): 854–880. |

| 11. | Jamieson, Ross W., "Material Culture and Social Death: African-American Burial Practices," Historical Archaeology 29 (1995): 39–58; John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978). |

| 12. | Thompson, Robert Farris, Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy (New York: Random House, 2010); Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, 142; Savannah Unit Georgia Writers' Project Work Administration, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1940). |

| 13. | Linda Wheeler, "Black Church Honors it Historic Cemetery," Washington Post, October 14, 1997. |

| 14. | Theresa Vargas, "Someone Keeps Leaving Toys and Birthday Cards at a 7-Year-Old's Grave in a Historic Black Cemetery. No One Knows Who," Washington Post, April 17, 2021. The marker has catalyzed speculation and a series of commemorative art works, including by artist Lindsey Brittain Collin, inspired by dolls left at Nannie's graveside. |

| 15. | Mary Mitchell, "'I Held George Washington's Horse': Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia," Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, DC 63/65 (1963–1965): 221–229; Reidy, Joseph P, "The Winding Path to Freedom under the District of Columbia Emancipation Act of April 16, 1862," Washington History 26, no. 2 (2014): 18–22. The complex relationships between enslaved and free persons of color in the antebellum District of Columbia are examined in Mary Corrigan, "A Social Union of Heart and Effort: the African-American Family in the District of Columbia on the Eve of Emancipation" (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 1996). The broader context of DC emancipation is addressed in Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). |

| 16. | Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 6, 1856, 3. |

| 17. | Paul E. Sluby and Stanton L. Wormley, eds., Register of Burials of the Joseph F. Birch Funeral Home, Volume I, (Washington, DC: Columbian Harmony Society, January 1, 1847–April 12, 1864). Also available as FamilySearch microfilm #008135478. Note that a reference to "William Tenney child," is not listed in in Pippenger, District of Columbia Interments. |

| 18. | Francis's father William appears in a November 15, 1827 District of Columbia manumission record:

"Know all men, by these Presents that I Charles Teney of Washington County in the District of of Columbia for divers good causes and considerations, me thereunto moving [?] and also in further consideration of the sum of one dollar to me in hand paid have released from slavery, liberated and manumitted and set free, and by these present do release from slavery, liberated and manumit and set free my slave woman named Matilda Teney aged about thirty five years, and her three children Anne aged about thirteen years, Andrew aged about three years and William Don Otious aged about 19 months, and able to work and gain a sufficient livelihood and maintenance, which said mentioned slaves were obtained by me as heir at law of my son William Don Otious Teney late of said County deceased, and them the said Matilda and her three children, Ann Andrew and William Don Otious I do declare to be henceforth free, manumitted and discharged from all manner of servitude and service to me and my executors, administrators, or assignees forever. In presence of Lemuel J Middleton and A Balmance." Two other candidates for "Nannie" are suggested by comparing the 1850 and 1860 censuses: (A) The daughter "Ann" (born about 1848) of freed-people Francis Yates and Caroline (Smith) Yates, who later took the surname Cole, does not appear in the records after 1850. Francis and Caroline married three months before the birth of the "Nannie" memorialized on the headstone. Anna Yates, Black, one year old, died 10 August 1857 and was buried in Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal burial ground; she may be related, but is clearly a different person; (B) Ann E. Twine, the daughter of coachman David Twine and his wife Caroline Gray Twine, both free persons of color in the District. David Twine was interred in Mount Zion in 1894. A member of Metropolitan A.M.E., David Twine came from a family with long connections to Georgetown and the local Black Methodist community. Both of these girls appear in the 1850 census but are not enumerated in the 1860 census or other records. However, Ann E. Twine may appear in the 1860 census as "Eliza Twine", ten years old, living with an older couple that may be her grandparents. Neither girl is indicated in the DC Register of Burials, so they seem much less likely candidates than the child of William Tenney, who died in May 1856 and who is recorded as interred in the "Colored Methodist Burial Ground." |