Overview

Grassroots organizer Ra'Niqua Lee addresses the "end" of the COVID public health emergency and the impact on mutual aid efforts in Atlanta and beyond. The collapsing of safety nets put in place in response to the pandemic will leave millions without the help they still need, but grassroots organizations have been filling gaps in government aid before COVID, and the work will continue.

In May of 2023, when the World Health Organization downgraded the coronavirus emergency from a global health pandemic to an "ongoing health crisis," the shift made sense in many ways. Most developed nations have made vaccines available for over two years. Shutdowns and enforced quarantines ended, even in holdout nations. The WHO's announcement signaled that other countries, including the United States, would follow suit if they had not already. This move, however, will have material consequences for grassroots charitable organizations across the US. Endstate ATL (ESA), a group I have worked with since 2021, is one of many non-profit groups that will be affected.

In Georgia, the COVID state of emergency officially ended in May 2022, even as it remained in place at the national level. This allowed organizations like ESA to continue our mutual aid work. But when the US announced the end of the Federal COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) Declaration on May 11, 2023, enhancements to public assistance and social safety net programs ceased. From this point on, groups like ESA once again will have to jump through multiple bureaucratic hoops to obtain the funding necessary to provide care.

Following the global outbreak of COVID in 2020 many governments created temporary measures to extend aid to vulnerable populations. In the US, these included extensions of unemployment benefits, a moratorium on student loan interest and payments, no-cost COVID testing and vaccinations, Medicare flexibility, and opportunities to provide nontaxable disaster relief funds. The national government also released relief funds to individual state governments, although often these funds did not reach the people who needed them.1Rebecca Riess and Devon M. Sayers, "Alabama Governor Signs Bill to Use Covid-19 Relief Funds to Build Prisons," CNN, October 1, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/01/politics/alabama-covid-relief-prison-bills-signed-governor-kay-ivey/index.html. Despite the uneven distribution of aid, many people, specifically children and elders, moved above the poverty line thanks to COVID assistance.2John Creamer, "Supplemental Poverty Measure That Accounts for Additional Government Benefits Lowest on Record at 7.8%," Census, September 13, 2022, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/government-assistance-lifts-millions-out-of-poverty.html.

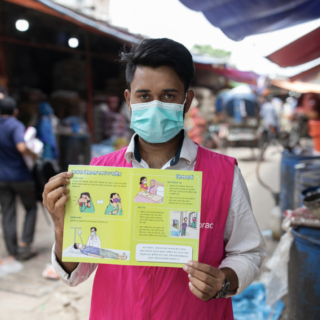

The flexibility surrounding nontaxable disaster relief funds eased mutual aid work. Mutual aid has a long history in the US and Global South, and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic witnessed an outpouring of community solidarity towards those in need. Mutual aid stands apart from other charity models because of its non-hierachal emphasis on mutualism rather than models that maintain divisions between givers and receivers. Mutual aid is rooted in reciprocity.

Endstate ATL took advantage of these temporary measures for the betterment and aid of our community members. Rooted in southwest Atlanta with a Black queer feminist politic, ESA's work aims to reach those most marginalized through community building, political education, and mutual aid. Through our Black Power Fund, which pays up to three months' worth of utility bills for Black queer households, and our Pack Provides Programs, which provide household supplies, COVID PPE, and infant essentials including formula, clothing, and sanitary products to caregivers of young children, we seek to step in where the state fails to provide support.

Mutual aid allows organizations to provide immediate care and relief to individuals in need without imposing the bureaucratic processes that often keep aid beyond reach. Under a state of emergency, disaster relief payments are not taxable. As such, ESA, and other groups like it, were able to provide direct aid through a less convoluted system of reporting and disbursement. This allowed us to move funds directly and rapidly to people in need and has been crucial to our ability to substantively support people in a timely way. ESA has covered bills for ten households in the past year, as well as covered a year of utilities for the BARRED Business house, which provides stable, community-owned housing for people recently released from prison. We have been able to report these funds as disaster relief.3"Mutual Aid Legal ToolKit," Sustainable Economies Law Center, Accessed June 22, 2023, https://www.theselc.org/mutual_aid_toolkit.

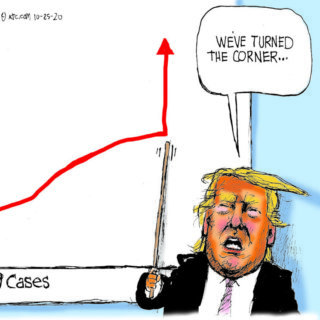

The efforts of mutual aid groups helped supplement aid where state and local leadership failed. Georgia governor Brian Kemp refused to take the COVID-19 pandemic seriously. In 2020, Georgia was the first state in the nation to relax quarantine restrictions, even as Kiesha Lance Bottoms, the mayor of Atlanta, sought to retain many protective measures. Initial reporting that the virus would largely impact the elderly and immunocompromised, combined with anti-fear government propaganda, engendered a sense of invincibility and an attitude of disregard among many Georgians. As of 2021, Georgia had one of the highest COVID mortality rates in the US, and those most impacted were poor, working class, and people of color.4"COVID-19 Mortality by State," CDC, Accessed June 22, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/covid19_mortality_final/COVID19.htm. The refusal of Governor Kemp to implement mandated social distancing or mask requirements, even before vaccines were available, left the entire state population vulnerable to infection. The consequences were devastating, with thousands of unnecessary deaths and debilitating outcomes for those suffering from long COVID.

Pandemic relief payments meant to alleviate the burden of rising interest rates were out of reach for marginalized Georgians. In order to receive national stimulus checks and Kemp's own "special tax credit," individuals needed to have filed and paid taxes for the preceding two years, a barrier that left people who were unemployed or homeless without access to relief.5"Gov. Kemp Announces First Round of This Year's Special Tax Refund," Department of Revenue, May 1, 2023, https://dor.georgia.gov/press-releases/2023-05-01/gov-kemp-announces-first-round-years-special-tax-refund#:~:text=Single%20filers%20and%20married%20individuals,a%20maximum%20refund%20of%20%24500.

In response to the pandemic, groups emerged such as Bed Stuy Strong, based in Brooklyn, which created a robust grocery delivery system by first relying on the resources at their disposal before evolving into a program that benefited thousands.6Haritha Kumar, "Four Key Takeaways from Mutual Aid Organizing During the COVID-19 Pandemic," Georgetown University Beeckcenter, October 4, 2022, https://beeckcenter.georgetown.edu/four-key-takeaways-from-mutual-aid-organizing-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/. Georgia has similar organizations. Community Movement Builders developed stabilization programs that include rent/mortgage payments as well as groceries in their efforts to impede the gentrification of southwest Atlanta, and Food4Lives a non-profit started by Georgia Tech and Emory students provides food and supplies for the unhoused in the greater Atlanta area.7Katie Burkholder, "Housing as a Human Right: Community Movement Builders Organize Against Gentrification," Georgia Voice, April 21, 2022, https://thegavoice.com/today-in-gay-atlanta/housing-as-a-human-right-community-movement-builders-organize-against-gentrification/; "Who are We?" Food4Lives, Accessed June 22, 2023, https://food4lives.org/about.html. Both organizations preceded the pandemic, but their work became much more indispensable in its wake.

The increase in groups doing this aid work was significant, especially in red states where Republican leadership champions laissez-faire government structures for almost everything but reproductive health, policing, and surveillance. Pandemic or no pandemic, people need help. However, smaller aid groups face difficulties in keeping the work going. ESA has primarily been funded by grants, a funding model that is not easily sustainable. According to one of our members, "A significant struggle we've faced since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is the philanthropic and public perception that the conditions for folks have changed enough that mutual aid is not necessary even as we continue to field a significant number of requests." Further, all members participate on a volunteer basis, spending much of our time otherwise as graduate students, teachers, doulas, herbalists, and nonprofit workers. Over the last two years, many of us have faced our own destabilizing events, financial uncertainty, bouts of COVID, and family loss. The ability of small groups to come together and push to make a difference in their communities—despite personal difficulties and decreasing assistance from governing bodies—should inspire more activism. But the question remains, how can we continue this work when governmental policies have resumed restricting social safety nets while offering few, if any, alternatives?

Changing policy is one problem organizers face, burnout is another. Studies have suggested that we approach "burnout as a part of activism and as influenced by the organizational context, rather than as something that individual activists experience outside of activism."8Maria Fernandes-Jesus et al., "More Than a COVID-19 Response: Sustaining Mutual Aid Groups During and Beyond the Pandemic," Frontiers in Psychology 12 716202, October 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8563598/. However, as young Black people organizing in the South, my colleagues and I experience burnout from many directions. We deal with the stress of everyday life, as well as the difficulty of doing our solidarity work, with constant reminders from government leadership that our goals are at odds with theirs.

With the COVID state of emergency ending in the US, aid provided by organizations such as Endstate ATL becomes taxable, dramatically altering the way funds can be mobilized, as well as the process that recipients must go through to receive support. Charitable tax deductions are reserved for individuals and corporations who donate money to qualified charities.9Up until December 2021, entities meeting these requirements were able to claim as much as 100% of their AGI in charitable tax write offs. "CARES Act Charitable Benefits Not Extended For 2022," Stanford Giving, March 14, 2022, https://giving.stanford.edu/stories/cares-act-not-extended-for-2022/. Because ESA puts money "directly" in the hands of marginalized people, such direct contributions to individuals are not tax-exempt. The COVID state of emergency allowed groups like ESA to move funds to individuals more freely—on an emergency basis. The end of the state of emergency means we must restructure our aid programs. The beautiful thing about mutual aid is that even if one group burns out, another group can and likely will step up right behind to fill the gap. In this way, the work continues. We never stop.

About the Author

Ra'Niqua Lee writes to share her particular visions of love and the South. She earned an MFA in fiction from Georgia State University, and she is currently at Emory pursuing a PhD in late nineteenth/early twentieth century African American literature with a focus on spatial and Black queer feminist theories. Her fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Cream City Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, Indiana Review, Passages North, Best of the Net 2023, Best Small Fictions 2023, and elsewhere. In 2021, the Georgia Writers Association awarded her the John Lewis Writing Grant for fiction. Her flash collection For What Ails You is forthcoming from ELJ Editions.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to my colleagues. Without their collaborative support, I would not be able to do this work: Julian Rose, Britni Ruff, Christina Foster, Michelle, Jovan Julien, and extra thanks to Hugh Hunter for his early edits.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy.

Beginning in 2022, the series expands to include 1000-word blog posts, as well as longer commentaries, essays, articles and media productions that address the public health and political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic from multiple perspectives. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Cover Image Attribution:

The Metropolitan Mural Project. Mural by and courtesy of Shamora Alakhum.Recommended Resources

Text

Kendall, Mikki. Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot. New York: Penguin Books, 2021.

Kropotkin, Pëtr. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. 1902. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-mutual-aid-a-factor-of-evolution.

Sitrin, Marina and Colectiva Sembrar. Pandemic Solidarity: Mutual Aid During the Covid-19 Crisis. London: Pluto Press, 2020.

Web

Carstensen, Nils, Mandeep Mudhar and Freja Schurmann Munksgaard. "'Let Communities do Their Work': The Role of Mutual Aid and Self-Help Groups in the Covid-19 Pandemic Response." Disasters 45, no. 1 (2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8653332/.

Fernandes-Jesus, Maria and Guanian Mao, Evangelos Ntontis, et al. "More Than a COVID-19 Response: Sustaining Mutual Aid Groups During and Beyond the Pandemic." Frontiers in Psychology 12:716202 (2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8563598/.

Hastings, Dorothy. "'Abandoned by Everyone Else' Neighbors are banding Together During the Pandemic." Nation, April 5, 2021. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-mutual-aid-networks-came-together-in-a-year-of-crisis.

Littman, Danielle M., Madi Boyett, Kimberly Bender et al. "Values and Beliefs Underlying Mutual Aid: An Exploration of Collective Care During the Covid-19 Pandemic." Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 13 no. 1 (2022). https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/716884.

Mao, Guanian, John Drury, Maria Fernandes-Jesus, et al. "How Participation in Covid-19 Mutual Aid Groups Affects Subjective Well-Being and How Political Identity Moderates These Effects." Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 21, no. 1 (2001). https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/asap.12275.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Rebecca Riess and Devon M. Sayers, "Alabama Governor Signs Bill to Use Covid-19 Relief Funds to Build Prisons," CNN, October 1, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/01/politics/alabama-covid-relief-prison-bills-signed-governor-kay-ivey/index.html. |

|---|---|

| 2. | John Creamer, "Supplemental Poverty Measure That Accounts for Additional Government Benefits Lowest on Record at 7.8%," Census, September 13, 2022, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/government-assistance-lifts-millions-out-of-poverty.html. |

| 3. | "Mutual Aid Legal ToolKit," Sustainable Economies Law Center, Accessed June 22, 2023, https://www.theselc.org/mutual_aid_toolkit. |

| 4. | "COVID-19 Mortality by State," CDC, Accessed June 22, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/covid19_mortality_final/COVID19.htm. |

| 5. | "Gov. Kemp Announces First Round of This Year's Special Tax Refund," Department of Revenue, May 1, 2023, https://dor.georgia.gov/press-releases/2023-05-01/gov-kemp-announces-first-round-years-special-tax-refund#:~:text=Single%20filers%20and%20married%20individuals,a%20maximum%20refund%20of%20%24500. |

| 6. | Haritha Kumar, "Four Key Takeaways from Mutual Aid Organizing During the COVID-19 Pandemic," Georgetown University Beeckcenter, October 4, 2022, https://beeckcenter.georgetown.edu/four-key-takeaways-from-mutual-aid-organizing-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/. |

| 7. | Katie Burkholder, "Housing as a Human Right: Community Movement Builders Organize Against Gentrification," Georgia Voice, April 21, 2022, https://thegavoice.com/today-in-gay-atlanta/housing-as-a-human-right-community-movement-builders-organize-against-gentrification/; "Who are We?" Food4Lives, Accessed June 22, 2023, https://food4lives.org/about.html. |

| 8. | Maria Fernandes-Jesus et al., "More Than a COVID-19 Response: Sustaining Mutual Aid Groups During and Beyond the Pandemic," Frontiers in Psychology 12 716202, October 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8563598/. |

| 9. | Up until December 2021, entities meeting these requirements were able to claim as much as 100% of their AGI in charitable tax write offs. "CARES Act Charitable Benefits Not Extended For 2022," Stanford Giving, March 14, 2022, https://giving.stanford.edu/stories/cares-act-not-extended-for-2022/. |