Overview

In this media-enhanced excerpt from Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021), Daphne A. Brooks delves into Zora Neale Hurston's 1939 experiences as the only Black woman on the staff of the Federal Writers Project's Florida Guide. A keen listener, interviewer, and ethnographer, Hurston, as heard in these recordings, was also a sonic interpreter of vernacular voices and performance styles.

Songs Cover the Landscape

Yet another program housed under the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Federal Writers Project (FWP), invited Zora Neale Hurston in 1938 to join the editorial staff of The Florida Guide, part of an "American Guide" series designed to "hold up a mirror to America." The gig provided her with the opportunity to sharpen her ethnographic game, and through her WPA activities and assignments, she began to move closer toward both recording and performing her folk music findings out in the field. According to her colleague Stetson Kennedy, she collected "fabulous folksongs, tales, and legends, possibly representing gleanings from days long gone by." She also drafted reports on the music of local church services and filed an essay on Florida folklore and music entitled "Go Gator and Muddy the Water." Hurston did all of this in spite of her steadfast autonomy as a member—the only Black woman member—of the editorial staff (the lowest paid and yet, according to Kennedy, quite likely the most experienced). In this context, she emerged as the ideal candidate to participate in a statewide recording expedition organized by the FWP.1 Valerie Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston (New York: Scribner, 2004), 313; Kennedy as quoted in Boyd, 318. Says Kennedy, "She had already published her first two books by that time, but she wanted a job and was given the same job title that I had when I started out. I was junior interviewer. Imagine Zora Hurston, junior interviewer. She had already had her degrees from Boaz (sic) and Columbia and Barnard and so on." "The Sounds of 1930s Florida Folklife," All Things Considered, February 28, 2002, NPR Hearing Voices, http:// hearingvoices.com/transcript.php?fID =23. In his unpublished manuscript on Hurston's career and his time working with her on what became known as the "Negro Unit" of the FWP, Kennedy notes that Hurston was given the title of "Junior Interviewer" and paid "$67.20 per month" for her work with the WPA. "Ironically," Kennedy adds, "the typist at the Negro Unit" in Jacksonville "was paid $5.00 per month more than Zora, by virtue of a higher urban wage scale." Stetson Kennedy, "Alan Lomax/Zora Neal Hurston Field Trip of 1935 . . . As Described by Alan [Lomax] to Stetson Kennedy," Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged, n.d., George A. Smathers Library, University of Florida, Gainesville. However, Stetson remains a tricky figure when it comes to his own treatment of Hurston's legacy. He was a fierce champion of her legendary status, a jealous protector of his own archival materials related to their shared work for the WPA, and also a spectacularly harsh critic of Hurston's contradictory persona. See, for instance, his searing list of "SAD-BUT-TRUE ASPECTS of Zora" which includes a range of inflammatory monikers including "THE SELF-STYLED 'PET DARKEY' . . . NO RACE CHAMPION . . . THE LICKER OF THE WHIP HAND, THE 'HOUSE NIGGER' . . . THE RACISTS' DARLING," "THE ARCH REACTIONARY," and "THE 24-KARAT BITCH." The latter insult Kennedy attributes to Alan Lomax, quoting him as having said that in "the field, Zora was absolutely magnificent—but of course you know she was a 24-karat bitch. . . ." Kennedy, "SAD-BUT-TRUE ASPECTS OF ZORA," September 5, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. Kennedy wrote obsessively about Hurston in a range of published material and unpublished material that recycled and occasionally reworked versions of the aforementioned list of traits he logged. See, for instance, Kennedy, "Almost all I know about Zora," unpublished manuscript, September 5, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. Kennedy, untitled ("I am the one who wrote, in my Tribute to Zora . . ."), unpublished manuscript, September 8, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research.

In the eyes of Ben Botkin, the FWP folklore program's new national director, "mere written transcriptions did not provide enough detail and ambience," and so he turned to Hurston and crew to turn up the volume in the wetlands. "When she first came on board and scheduled a visit to our (lily-white) state office," recalls Kennedy, "a staff conference was convened at which we were admonished that 'we would have to make allowances for Zora, as she had been lionized by New York café society, smoked cigarettes in the presence of white people,' etc. And so she did, and so we did."2Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 322; Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 6, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research.

It was not a situation without stress for her. Writing in late 1938 to state FWP director Carita Doggett Corse, Hurston noted her personal battle with a "form of phobia," a crushing and incapacitating depression that left her unable to "write, read, or do anything at all for a period." Having assured her "Boss" in that letter that when she does "come out of" such spells, it is "as if [she] had just been born again," Hurston nonetheless was plagued at times with questions about how best to make sense of her inner turmoil in relation to her intellectual and artistic pursuits. In her letter to Corse, she ponders the reasons for her despair and notes that she finds that such spells are often "the prelude to creative effort."3Zora Neale Hurston to Carita Dogget Corse, December 3, 1938, in Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (New York: Anchor, 2003), 417–418. By summer of the following year, she was rolling with the FWP crew and about to embark on some of her most fascinating and unique methods of research.

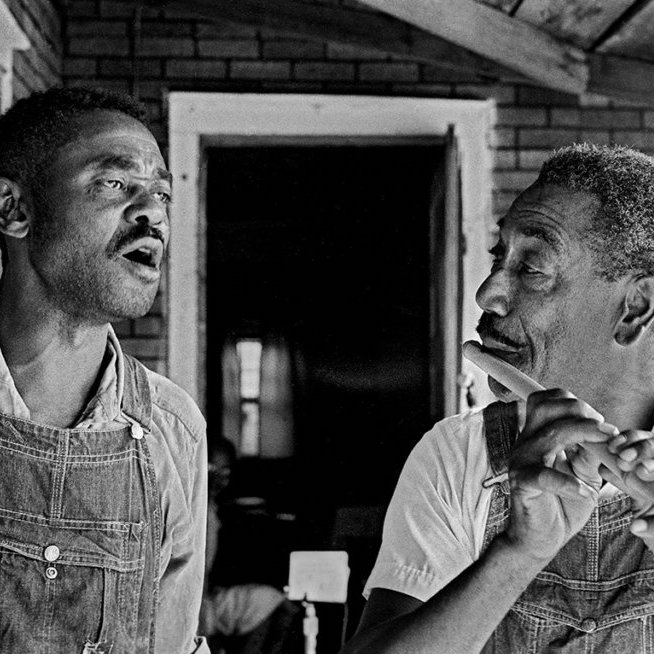

Bottom, Zora Neale Hurston with Rochelle French and Gabriel Brown, Eatonville, Florida, June 1935. Photograph by Alan Lomax. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Some four years after the publication of what would become two of her most famous essays, folklorist Herbert Halpert and a crew of fellow WPA workers recorded Hurston on June 18, 1939, performing a range of rollicking vernacular songs down on the Florida peninsula in Jacksonville. Here she and her Florida guide colleagues had set up camp, among them Corse, "twenty-something" Halpert, and local student-turned-project supervisor Kennedy. On site in Jacksonville, Halpert had on hand a recording device "the size of a coffee table—the moving parts looked like a phonograph—and cut recordings with a sapphire needle directly onto a 12-inch acetate disk." For her part, Hurston had, along with her fellow Black FWP colleagues, rounded up "a group of railroad workers, musicians, and church ladies at the Clara White Mission on Ashley Street, a landmark institution in Jacksonville's Black community." There, Halpert "used his cumbersome recording machine to capture the voices of various informants singing, telling stories, and occasionally hamming it up for posterity."4"Sounds of 1930s Florida Folklife." Kennedy traces the recorder back to "the Hurston/Lomax/Barnicle team," pointing out that the team "borrowed the recorder of the Library of Congress" because of Lomax's father's ties to that institution. "In those pre-tape days," he muses, recorders "consisted of a heavy monstrosity. . . ." After joining the FWP, "Zora was able to again wangle it on loan from the Library of Congress" Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 62–63, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. Bordelon further points out that Halpert would arrive in Jacksonville "with the equipment carefully stored in a converted World War I ambulance outfitted by workers from the Federal Theater Project. . . . He was one of the few folklorists with field recording experience. He knew how to transport, repair, and set up the cumbersome equipment as well as how to conduct the first-person interviews, an integral part of the recording sessions." "Zora Neale Hurston," Go Gator and Muddy the Water: Writings by Zora Neale Hurston from the Federal Writers Project, ed. Pamela Bordelon (New York: Norton, 1999), 45; Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 324.

Hurston's approach to this whole operation was always distinct, always bent on both reproducing precious sounds through her own performance practices and yet still capitalizing on the quirks and the character of her own interpretative skills. This is Zora's form of phonography, that which loops together a zone in which she operates at the crossroads of the modern and the folk. On tape, one hears a forty-eight-year-old Hurston (who brashly claims for the record that she is thirty-five) both collaborating with and also facing off against Halpert's bulky, furniture-sized machine to offer her own definitive repertoire of southern vernacular culture for the archive. A copy of Halpert's "Tentative Record Check List" from these sessions dated March 12–June 30, 1939, offers a detailed account of songs sung by Hurston and other local interlocutors (for example, "Beatrice Long (white) age 35"; "Rev. H. W. Stuckey, age 43, blind Negro preacher"). Both a playlist of sorts and an archival testimony to this sister's exhaustive performative dynamism, her mad flow, and her tireless and meticulous attention to the cultural eccentricities manifest in the songs themselves, Halpert's "record check" documents Hurston's instructive commentary and her magnetic presence on these expeditions. These are notes that follow the rhythms of her explanatory cues, the distinctions that she makes between, say, a "jook song" and a "lining" accompaniment, her references to her own ethnographic prowess ("Miss Hurston describ[es] how she collects and learns songs (including those she has published)"). The labor of it all lurks in the parentheses as well, as in the bracketed moment when Halpert indicates that "Miss Hurston was tired (in part) and accidentally tacked songs together." This is the document of her marathon performances, her critical acuity in the realm of listening, performing, and, by extension, arranging the sounds that she encounters, stores, and "carrie[s] . . . in her memory" from the heart of the field right into the center of those scholarly circles awaiting her return.5Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 325; Bordelon, "Mule on the Mount" transcription, 163–164; Herbert Halpert, "Tentative Record Check List: southern recording expedition," March 12– June 30, 1939, Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern States Recording Expedition (AFC 1939/005), Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Kennedy maintains that it was his "bright idea" to "sav[e] travel money," "summo[n]" Hurston to Jacksonville, "si[t] her down in a chair, and recor[d] all the folkstuff she carried around in her head," and he looked to Halpert, who was "using the machine at the time," to "collaborate in interviewing" her. Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 64, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research.

By way of Zora's phonography, we are made privy to a listening to a listening: Kennedy and Halpert and Corse and others lean in and pose questions as they strain to follow Hurston's musical cartography of folk songs, work chants, and blues and children's songs gathered up in the American South and the Caribbean diaspora, from the Bahamian "Crow Dance" to the swinging "Charleston rhythms" of "Oh the Buford Boat Done Come," music picked up by Hurston from a South Carolina Geechee country woman she met in Florida. She stands at the center of it all, shifting fluidly between the role of the folklorist and that of the informant, melding songs with communal lore, sketching out their sociocultural context and utility, and belting them out for a wonkish gaggle of folklore scholars, a captive audience who, nonetheless, prods her for details. Scholarly jostling ripples as an undercurrent in these sessions. But Hurston the pro brings all her swagger to these proceedings; she brings all of her skills to bear/bare in her vocal aesthetics of song, the means through which she might put the wonder and specificity of Black sonic art on the Florida map once and for all.6Kennedy's version of this recording expedition occasionally frames Hurston as the object of ethnographic inquiry rather than as a fellow collaborator ("I had gotten into the habit of asking my informants if they knew any 'dirty songs.' As it turned out, they knew plenty. . . . I asked Zora if she knew a song called 'Uncle Bud.'"). Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 64, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. The Library of Congress website lists both Halpert and Kennedy as "speakers" along with Hurston on various recordings from these sessions. Elsewhere Kennedy elaborates on the team's working conditions, describing how, "in recent years when asked to speak on the subject 'Working with Zora' . . . I have been tempted to suggest that the title 'Trying to Get Zora to Work' would be more appropriate. Like many of us who were on our own out in the field (again myself included), production was sporadic." Stetson Kennedy, "Zora's Contributions," n.d., unpublished manuscript, n.p., Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged. Kennedy was one of Hurston's greatest defenders and also one of the most consistent critics of her well-known ambivalences when it came to racial uplift politics, her "accomodationist-if-not apologist" leanings, as he puts it. But repeatedly in his manuscript, he argues that "we and generations yet to come should focus upon how Zora Neale Hurston wrote, not how she voted." Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 68, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged. See also Kennedy, "sad-but-true aspects of zora," unpublished manuscript, September 5, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. For more on Hurston's political leanings, see Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows.

Songs cover the landscape like regional quilts in Zora Neale Hurston's musical repertoire. As she lets loose on "Mule on the Mount," "the most widely distributed work song in the United States," we hear the varied shades and moods of Black regional experience as verses shift and change according to locality. Hurston's fascination with blues dissonance clearly undergirds her theories of Black performance, her liner notes for the recordings still to come when, for instance, she highlights the importance of both angularity (performances that stress the "angles" of bodily expression) and especially asymmetry ("the abrupt and unexpected changes. The frequent change of key and time . . ."). We can hear her working this blues aesthetic out in songs like "Mule on the Mount," that lining rhythm that we might think of as a Hurston, folkified version of "Wartime Blues" since, as is perhaps implicit in her prefatory comments, it shares moments of startling narrative discordance and social upheaval with that Blind Lemon Jefferson blues classic.

Hurston: This song I am going to sing is a lining rhythm, and I am going to call it "Mule on the Mount," though you can start with any verse you want and give it a name. And it's the most widely distributed work song in the United States . . . it has innumerable verses and whatnot, about everything under the sun. . . . [Black folk] sometimes sing it just sitting around the jook houses and doing any kind of work a t'all. . . .Everywhere you'll find this song. Nowhere where you can't find parts of this song. . . .

Halpert: . . . Is it a consistent song . . . as you hear it all over?

Hurston: The tune is consistent, but . . . the verses, you know . . . every locality you find some new verses everywhere. . . . There is no place that I don't hear some of the same verses. . . .

Halpert: Where did you learn this particular way?

Hurston: Well, I heard the first verses, I got in my native village of Eatonville, Florida, from George Thomas.

Halpert: And is . . . that the only version you're going to sing?

Hurston: The tune is the same. I am going to sing verses from a whole lot of places.

Halpert: All right.7Zora Neale Hurston, "Mule on the Mount," Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern States Recording Expedition, AFC 1939/005: AFS 03136 B01, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/item/flwpa000008/.

If the trope of the mule recurs in Hurston's literary and ethnographic writing most famously as a feminized beast of burden, in this song from "everywhere," it is the vehicle that the masculinist singer "rides down" in the opening verse, replaced in the second verse by "a woman" who "shakes like jelly all over." "Mule on the Mount" is, by no means, a feminist revision of sexist vernacular culture, as it transitions into a stock tale of paranoia and betrayal ("My little woman, she had a baby this morning. . . . He had blue eyes"), alienation and revenge ("And I told her, must be the hellfire cap'n Ha! . . . I got a woman. She won't live long, lawd, lawd, she won't live long"). However, it is a song that emerges in her research and performance as raw material that showcases the ways sonic folklore might serve as the connective tissue that ties dispersed Black peoples together through improvisational innovation, as well as temporally and geographically distant modes of collaboration.8Bordelon transcription of "Mule on the Mount," Bordelon, Go Gator, 163–164; Hurston, "Mule on the Mount." Like the protagonist in Jefferson's ode to estrangement and wandering, the tragic hero of Zora's mule tale retold breaks by the fourth verse onto another plane, away from the arrival of the "blue-eyed baby," the product of probable betrayal and potential racialized sexual violation, away from "the hellfire," and turns instead toward the sound of "a cuckoo bird" that "keep a hollerin' Ha! . . . It look like rain, lawd, lawd, it look like rain."9Blind Lemon Jefferson's 1926 "Wartime Blues" makes use of the blues form's "floating verses," oft-repeated verses in Black radical tradition lore, and ones that reference familiar images, for instance, "trains" and "rivers" and tropes evocative of African American rural and migratory life. Such visions and figures and themes "float" from one song to another and can sometimes take shape as jarring abstractions, as thematic non-sequitar. But in every case, they are manifestations of both a dispersed and disrupted culture and the innovative contemplation of and rejoinder to quotidian and ubiquitous crisis. Blind Lemon Jefferson, "Wartime Blues," Release # 12425A, Matrix # 3070, Take #1, The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records, Vol. 1 (1917–1932) (Third Man Records-Revenant Records, 2013). For more on blues aesthetic traditions, see also Scott Blackwood's monumental work on the archive of Paramount recordings. Scott Blackwood, The Red Book liner notes for The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records, Vol. 1 (1917–1932); and Chapter 7. The pivotal fifth verse, and one that would become a signature line in Hurston's repertoire—"I got a rainbow wrapped and tied around my shoulder/It look like rain, lawd, lawd, it look like rain"—is the most telling break in the song, and it is the kind of rupture that Hurston would capitalize on in her role as a "signifying ethnographic" critic of Black sound. With that technicolor coat supplying crucial cover, the heroine of "Mule on the Mount" stands both outside and inside the song's wending, epic narrative. It may pour cats and dogs all around her, this song suggests, but she stays the course all bundled up in a mystical garment. Here in this place, caught in this storm and yet sheltered from it, she is traveling at her own angle against and through the elements. Moving to her own soundtrack, she possesses the equipment to stay in motion and keep the music alive. She wraps that "rainbow . . . tightly around [her] shoulder" and heads on out into the territory that is Black America, picking up exquisite sound, peculiar sound, vital sound all along the way.10Hurston, "Mule on the Mount."

Hurston on the Open Road

"My search for knowledge of things," Hurston muses in her conundrum of a memoir Dust Tracks on a Road, "took me into many strange places and adventures. My life was in danger several times. If I had not learned how to take care of myself in these circumstances, I could have been maimed or killed on most any day of the several years of my research work." Still more, Carla Kaplan makes plain in her edited edition of Hurston's letters how wary she is of "romanticiz[ing] Hurston with Model T and pistol, searching out 'the Negro farthest down' and 'woofing' in 'jooks' along the way." The "truth is," Kaplan contends, "that she worked hard under harsh conditions: traveling in blistering heat, sleeping in her car when 'colored' hotel rooms couldn't be had, defending herself against jealous women, putting up with bedbugs, lack of sanitation, and poor food in some of the turpentine camps, sawmills, and phosphate mines she visited."11Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road (New York: Harper Perennial, 1996, 146; Carla Kaplan, "'De Talkin Game': The Twenties (and Before)," in Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (New York: Anchor Books, 2002), 51–52. With regards to the opacity of Dust Tracks, Maya Angelou's 1995 foreword to the book is instructive. Angelou famously observes of Dust Tracks that "the author stands between the content and the reader. It is difficult, if not impossible, to find and touch the real Zora Neale Hurston" (xii). But as she was prone to "wandering" in "spirit," if not always in "geography" and "time," as she would describe it in her memoir, the automobile proved useful as a source of refuge from Jim Crow danger on more than one occasion for her, particularly as "racially 'mixed' teams" of WPA field researchers "travelling together were virtually unheard of." For these reasons, her "beat-up Chevy" was, more often than not, always her most dependable shelter.12Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road, 67. See also Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 57. Fellow FWP recording expedition team member Kennedy recalls Hurston's time in the field with him "record[ing] more of the songs of migratory black workers in the Everglades mucklands." Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 63, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research.

Hurston turned to her engine of modernity to gather up, cultivate, and disseminate songs that played with and through time and space and that called attention to the scale and depth of Black community. . . . The songs are the cars that she drives and the vehicles that carry her listeners into the "imagined cartographies" of Black migrants all at once, working out the politics of spirited togetherness as well as passionate longings and everyday dislocations as her vocal wheels keep turning. They are the sounds that stored up a kind of complex counterknowledge to that which irked Hurston, the seemingly knee-jerk rendering of southland Black life that defined it as steeped in suffering and nothing but.13Marti Slaten, Email message to the author, Jan. 13, 2011. Josh Kun would most certainly identify the "audiotopian" sites of cultural memory, communal questing, and questioning in Hurston's sounds. Josh Kun, Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Concerning this noted Blackness and suffering trend, redolent in the work of some of her most prominent 1930s contemporaries like George Gershwin and Richard Wright, she lamented in a 1936 letter that "some writers are playing to the gallery. That is, certain notions have gotten in circulation about conditions in the south and so writers take this formula and workout so-called true stories." Zora Neale Hurston to Stanley Hoole, March 7, 1936, Folder 60, Box 2, Zora Neale Hurston Papers.

I heard "Halimuhfack" down on the . . . East Coast. . . . I was in a big crowd, and I learned it in the evening [in] the crowd. . . . I learned it from the crowd. [Zora singing]: "You may leave 'n go to Halimuhfack, but my slowdrag will bring you back. Well, you may go, but this will bring you back. I been in the country but I move to town. I'm a toe-low shaker from a head on down. Well you may go but this will bring you back. . . . Some folks call me a toe-low shaker, it's a doggone lie. I'm a backbone breaker. Well you may go, but this will bring you back. Oh you like my peaches but you don't like me. Don't you like my peaches, don't you shake my tree? Oh well you may go but this will bring you back. Hoodo! Hoodo! Hoodo do working! My heels are poppin' . . . my toenails crackin'. Well you may go, but this will bring you back."14Zora Neale Hurston, "Halimuhfack," Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern State Recording Expedition, AFC 1939/005: AFS 03138 B02, recorded in Jacksonville, Florida, June 18, 1939, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov /item/flwpa000014/.

You can hear Hurston relishing the wicked innuendos running amuck in "Halimuhfack," a jook song she'd "heard down on the East Coast" of Florida and one that exudes the "slow and sensuous" rhythms of the jook, that undercommons gathering place where, as she would famously insist, Negro theater originates, where "bawdiness" and "pleasure" erupt out of a smoldering elixir of song, dance, and inspired instrumentation.15Zora Neale Hurston, "Characteristics of Negro Expression," in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert O'Meally (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 306–309. All taunt and gentle seduction, Hurston the singer/interpreter gamely seizes on the mischievous wonder of a song that nonetheless documents and archives Black geographies in flux. It is a song that calls attention to the "imbrication of material and metaphorical space."16 Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiii. McKittrick calls these kinds of "clandestine geographic-knowledge practices" the "spaces of black liberation" that were "invisibly mapped across the United States and Canada and that this invisibility is, in fact, a real and meaningful geography. . . . the unmapped knowledges" (18). These "black geographies," she argues, "are deep spaces and poetic landscapes, which not only gesture to the difficulties of existing geographies and analyses, but also reveal the kinds of tools that are frequently useful to black social critics" (21–22). As Hurston would describe it in her "Folklore" manuscript chapter for the FWP, "Halimuhfack" is a "blues song" whose "title is a corruption of the Canadian city of Halifax. The extra syllables are added for the sake of rhythm."17Zora Neale Hurston, "First Version of Folklore," n.d., manuscript, Box 12, Zora Neale Hurston Papers. Pamela Bordelon includes "the third and final draft of the folklore and music chapter for The Florida Negro" in her collection of Hurston's transcribed FWP writings, but she spells the title as "Halimufask." The song title in Hurston's "first version" is "Halimuhfack." See Zora Neale Hurston, "Go Gator and Muddy the Water," in Bordelon, Go Gator, 72. The Stetson Kennedy Papers include a Zora Neale Hurston "set list" of sorts with "Halimuhfack" listed as "Halimuhfact," as well as the handwritten additional lyric, "My slow drag will bring you back!" Black theater scholar Eric Glover notes that "Halimuhfack" appears in Hurston's script for Polk County as well. See Eric Glover, "By and About: An Antiracist History of the Musicals and Anti-musicals of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston" (PhD diss., Princeton University, 2017). Yet "extra syllables," the gateway to lyrical "corruption" here, are the beats that carry the song onto another plane of expressive recourse for African Americans managing the exigent pressures of Jim Crow life, the quest for equality, employment, and human sustenance. Like "Diddy-Wah-Diddy" and other "Negro mythical places" of Black folklore that she documents in her automotive guide writing, "Halimuhfack" is the site of the speculative, the not-here; it's the in-between world of mythical folklore and blues quotidian life.18Bordelon points out that one of the "Negro mythical places" included in her automotive guide excerpt, "'Diddy-Wah-Diddy' . . . [is] a magical destination where neither man nor beast had to worry about work or food. Both were magically supplied. They often laughed and dreamed of far-off 'Heaven,' pinning human qualities on its celestial inhabitants." Bordelon, "Zora Neale Hurston," 26. See also Christopher D. Felker, "'Adaptation of Source': Ethnocentricity and 'The Florida Negro,'" in Zora in Florida, ed. Steve Glassman and Kathryn Lee Seidel (Orlando: University of Central Florida Press, 1991), 149. Hurston's shrewd rhythmic elongation of a north-of-the-border place (a place where Black fugitives found shelter from those who sought to return them to US bondage) renders it unrecognizable, turns this place into something new, another site of Black flight with its own quixotic allure, matched only by the "slow drag" of a singer bold enough to try to seduce her lover to return.

"Halimuhfack" is a record of Florida Jim Crow life as it was lived in a felt relationship with space, place, and the land that our intrepid anthropologist criss-crossed by car. In her time working for the FWP—which, on the one hand, flexed its racism by hiring her "in a relief rather than an editorial-supervisory capacity" and yet, on the other hand, enabled her to "live and work out of her own home in Eatonville, a privilege extended to only a handful of writers nationwide"—Zora's taped performances exude the kind of adventurous independence that would ultimately inform the iconicity of her career.19Bordelon, "Zora Neale Hurston," 17. Her recordings also stand as sound evidence of "different knowledges and imaginations . . . ," they are the kind of recordings that hold out the promise of "call[ing] into question the limits of existing spatial paradigms and put[ting] forth more humanly workable geographies."20McKittrick, Demonic Grounds, xxvi–xxvii. Hurston's rendition of the song encapsulates the driving and oscillating Zora, the woman who was both of and in the crowd as well as whimsically positioned outside of it. Reveling in the taunt, sass, and sly insinuations of this jook song's chorus ("You may go but this will bring you back"), she inhabits the playful ("Hoodo! Hoodo!") and the flirtatious energy of the tune while also wistfully stretching out the song's melancholic lyrics ("You may go but this will bring you back"), lyrics that signal lapsed love, abrupt departures, and the sting of abandonment. She translates into sonic feeling "geographic patterns that are underwritten by black alienation from the land."21McKittrick, 5. As the twinned pressures of the Great Migration and the Depression continued on through the thirties, songs like "Halimuhfack" captured the entwined sounds of vibrant, ingenious, raucous communal sociality and movement; sober, individual despair; and a deep bone will to survive and thrive in the face of enormous socioeconomic and regional transformations. Inside the massive archive that is Zora's playlist, in the anatomy of each of these big, colorful and complex songs of the self, Black folks make their own time while the wheels keep turning round and round.

About the Author

Daphne A. Brooks is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of African American Studies, American Studies, Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and Music at Yale University. She is the author of Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), winner of The Errol Hill Award for Outstanding Scholarship on African American Performance from the American Society of Theatre Research; Jeff Buckley's Grace (New York: Continuum, 2005); and Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Harvard University Press, February 2021).

Recommended Resources

Text

Boyd, Valerie. Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Scribner, 2004.

Brooks, Daphne A. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Garner, Lori Ann. "Representations of Speech in the WPA Slave Narratives of Florida and the Writings of Zora Neale Hurston." Western Folklore 59, no. 3–4 (2000): 215–31.

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. New York: W.W. Norton, 2019.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Mules and Men. New York: HarperCollins, 2008. First published 1935 by J.B. Lippincott Co. (Philadelphia).

Meisenhelder, Susan. "Conflict and Resistance in Zora Neale Hurston's Mules and Men." Journal of American Folklore 109, no. 433 (1996): 267–88.

Web

Graham, Adam H. "Forgotten Florida, Through a Writer's Eyes." New York Times. March 31, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/04/travel/04culture.html.

New York Public Library Staff. "The Sounds of Black Music: Folk Voices." New York Public Library Blog. June 15, 2021. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2021/06/15/sounds-black-music-folk-voices.

Onnekikami, Tunika. "Keeping the Memory of Zora Neale Hurston Alive in a Small Florida City." Atlas Obscura. December 6, 2021. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/zora-neale-hurston-trail-fort-pierce.

"Zora Neale Hurston and the WPA in Florida." Florida Memory at the State Library and Archives of Florida. Tallahassee, FL. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.floridamemory.com/learn/classroom/learning-units/zora-neale-hurston/documents/stetsonkennedy/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Valerie Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston (New York: Scribner, 2004), 313; Kennedy as quoted in Boyd, 318. Says Kennedy, "She had already published her first two books by that time, but she wanted a job and was given the same job title that I had when I started out. I was junior interviewer. Imagine Zora Hurston, junior interviewer. She had already had her degrees from Boaz (sic) and Columbia and Barnard and so on." "The Sounds of 1930s Florida Folklife," All Things Considered, February 28, 2002, NPR Hearing Voices, http:// hearingvoices.com/transcript.php?fID =23. In his unpublished manuscript on Hurston's career and his time working with her on what became known as the "Negro Unit" of the FWP, Kennedy notes that Hurston was given the title of "Junior Interviewer" and paid "$67.20 per month" for her work with the WPA. "Ironically," Kennedy adds, "the typist at the Negro Unit" in Jacksonville "was paid $5.00 per month more than Zora, by virtue of a higher urban wage scale." Stetson Kennedy, "Alan Lomax/Zora Neal Hurston Field Trip of 1935 . . . As Described by Alan [Lomax] to Stetson Kennedy," Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged, n.d., George A. Smathers Library, University of Florida, Gainesville. However, Stetson remains a tricky figure when it comes to his own treatment of Hurston's legacy. He was a fierce champion of her legendary status, a jealous protector of his own archival materials related to their shared work for the WPA, and also a spectacularly harsh critic of Hurston's contradictory persona. See, for instance, his searing list of "SAD-BUT-TRUE ASPECTS of Zora" which includes a range of inflammatory monikers including "THE SELF-STYLED 'PET DARKEY' . . . NO RACE CHAMPION . . . THE LICKER OF THE WHIP HAND, THE 'HOUSE NIGGER' . . . THE RACISTS' DARLING," "THE ARCH REACTIONARY," and "THE 24-KARAT BITCH." The latter insult Kennedy attributes to Alan Lomax, quoting him as having said that in "the field, Zora was absolutely magnificent—but of course you know she was a 24-karat bitch. . . ." Kennedy, "SAD-BUT-TRUE ASPECTS OF ZORA," September 5, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. Kennedy wrote obsessively about Hurston in a range of published material and unpublished material that recycled and occasionally reworked versions of the aforementioned list of traits he logged. See, for instance, Kennedy, "Almost all I know about Zora," unpublished manuscript, September 5, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. Kennedy, untitled ("I am the one who wrote, in my Tribute to Zora . . ."), unpublished manuscript, September 8, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 322; Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 6, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. |

| 3. | Zora Neale Hurston to Carita Dogget Corse, December 3, 1938, in Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (New York: Anchor, 2003), 417–418. |

| 4. | "Sounds of 1930s Florida Folklife." Kennedy traces the recorder back to "the Hurston/Lomax/Barnicle team," pointing out that the team "borrowed the recorder of the Library of Congress" because of Lomax's father's ties to that institution. "In those pre-tape days," he muses, recorders "consisted of a heavy monstrosity. . . ." After joining the FWP, "Zora was able to again wangle it on loan from the Library of Congress" Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 62–63, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. Bordelon further points out that Halpert would arrive in Jacksonville "with the equipment carefully stored in a converted World War I ambulance outfitted by workers from the Federal Theater Project. . . . He was one of the few folklorists with field recording experience. He knew how to transport, repair, and set up the cumbersome equipment as well as how to conduct the first-person interviews, an integral part of the recording sessions." "Zora Neale Hurston," Go Gator and Muddy the Water: Writings by Zora Neale Hurston from the Federal Writers Project, ed. Pamela Bordelon (New York: Norton, 1999), 45; Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 324. |

| 5. | Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 325; Bordelon, "Mule on the Mount" transcription, 163–164; Herbert Halpert, "Tentative Record Check List: southern recording expedition," March 12– June 30, 1939, Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern States Recording Expedition (AFC 1939/005), Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Kennedy maintains that it was his "bright idea" to "sav[e] travel money," "summo[n]" Hurston to Jacksonville, "si[t] her down in a chair, and recor[d] all the folkstuff she carried around in her head," and he looked to Halpert, who was "using the machine at the time," to "collaborate in interviewing" her. Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 64, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. |

| 6. | Kennedy's version of this recording expedition occasionally frames Hurston as the object of ethnographic inquiry rather than as a fellow collaborator ("I had gotten into the habit of asking my informants if they knew any 'dirty songs.' As it turned out, they knew plenty. . . . I asked Zora if she knew a song called 'Uncle Bud.'"). Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 64, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. The Library of Congress website lists both Halpert and Kennedy as "speakers" along with Hurston on various recordings from these sessions. Elsewhere Kennedy elaborates on the team's working conditions, describing how, "in recent years when asked to speak on the subject 'Working with Zora' . . . I have been tempted to suggest that the title 'Trying to Get Zora to Work' would be more appropriate. Like many of us who were on our own out in the field (again myself included), production was sporadic." Stetson Kennedy, "Zora's Contributions," n.d., unpublished manuscript, n.p., Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged. Kennedy was one of Hurston's greatest defenders and also one of the most consistent critics of her well-known ambivalences when it came to racial uplift politics, her "accomodationist-if-not apologist" leanings, as he puts it. But repeatedly in his manuscript, he argues that "we and generations yet to come should focus upon how Zora Neale Hurston wrote, not how she voted." Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 68, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged. See also Kennedy, "sad-but-true aspects of zora," unpublished manuscript, September 5, 2000, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. For more on Hurston's political leanings, see Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows. |

| 7. | Zora Neale Hurston, "Mule on the Mount," Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern States Recording Expedition, AFC 1939/005: AFS 03136 B01, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov/item/flwpa000008/. |

| 8. | Bordelon transcription of "Mule on the Mount," Bordelon, Go Gator, 163–164; Hurston, "Mule on the Mount." |

| 9. | Blind Lemon Jefferson's 1926 "Wartime Blues" makes use of the blues form's "floating verses," oft-repeated verses in Black radical tradition lore, and ones that reference familiar images, for instance, "trains" and "rivers" and tropes evocative of African American rural and migratory life. Such visions and figures and themes "float" from one song to another and can sometimes take shape as jarring abstractions, as thematic non-sequitar. But in every case, they are manifestations of both a dispersed and disrupted culture and the innovative contemplation of and rejoinder to quotidian and ubiquitous crisis. Blind Lemon Jefferson, "Wartime Blues," Release # 12425A, Matrix # 3070, Take #1, The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records, Vol. 1 (1917–1932) (Third Man Records-Revenant Records, 2013). For more on blues aesthetic traditions, see also Scott Blackwood's monumental work on the archive of Paramount recordings. Scott Blackwood, The Red Book liner notes for The Rise & Fall of Paramount Records, Vol. 1 (1917–1932); and Chapter 7. |

| 10. | Hurston, "Mule on the Mount." |

| 11. | Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road (New York: Harper Perennial, 1996, 146; Carla Kaplan, "'De Talkin Game': The Twenties (and Before)," in Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (New York: Anchor Books, 2002), 51–52. With regards to the opacity of Dust Tracks, Maya Angelou's 1995 foreword to the book is instructive. Angelou famously observes of Dust Tracks that "the author stands between the content and the reader. It is difficult, if not impossible, to find and touch the real Zora Neale Hurston" (xii). |

| 12. | Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road, 67. See also Boyd, Wrapped in Rainbows, 57. Fellow FWP recording expedition team member Kennedy recalls Hurston's time in the field with him "record[ing] more of the songs of migratory black workers in the Everglades mucklands." Stetson Kennedy, unpublished manuscript, 63, Zora Neale Hurston Box 1, Stetson Kennedy Papers, uncataloged at the time of archival research. |

| 13. | Marti Slaten, Email message to the author, Jan. 13, 2011. Josh Kun would most certainly identify the "audiotopian" sites of cultural memory, communal questing, and questioning in Hurston's sounds. Josh Kun, Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Concerning this noted Blackness and suffering trend, redolent in the work of some of her most prominent 1930s contemporaries like George Gershwin and Richard Wright, she lamented in a 1936 letter that "some writers are playing to the gallery. That is, certain notions have gotten in circulation about conditions in the south and so writers take this formula and workout so-called true stories." Zora Neale Hurston to Stanley Hoole, March 7, 1936, Folder 60, Box 2, Zora Neale Hurston Papers. |

| 14. | Zora Neale Hurston, "Halimuhfack," Herbert Halpert 1939 Southern State Recording Expedition, AFC 1939/005: AFS 03138 B02, recorded in Jacksonville, Florida, June 18, 1939, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, https://www.loc.gov /item/flwpa000014/. |

| 15. | Zora Neale Hurston, "Characteristics of Negro Expression," in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert O'Meally (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 306–309. |

| 16. | Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiii. McKittrick calls these kinds of "clandestine geographic-knowledge practices" the "spaces of black liberation" that were "invisibly mapped across the United States and Canada and that this invisibility is, in fact, a real and meaningful geography. . . . the unmapped knowledges" (18). These "black geographies," she argues, "are deep spaces and poetic landscapes, which not only gesture to the difficulties of existing geographies and analyses, but also reveal the kinds of tools that are frequently useful to black social critics" (21–22). |

| 17. | Zora Neale Hurston, "First Version of Folklore," n.d., manuscript, Box 12, Zora Neale Hurston Papers. Pamela Bordelon includes "the third and final draft of the folklore and music chapter for The Florida Negro" in her collection of Hurston's transcribed FWP writings, but she spells the title as "Halimufask." The song title in Hurston's "first version" is "Halimuhfack." See Zora Neale Hurston, "Go Gator and Muddy the Water," in Bordelon, Go Gator, 72. The Stetson Kennedy Papers include a Zora Neale Hurston "set list" of sorts with "Halimuhfack" listed as "Halimuhfact," as well as the handwritten additional lyric, "My slow drag will bring you back!" Black theater scholar Eric Glover notes that "Halimuhfack" appears in Hurston's script for Polk County as well. See Eric Glover, "By and About: An Antiracist History of the Musicals and Anti-musicals of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston" (PhD diss., Princeton University, 2017). |

| 18. | Bordelon points out that one of the "Negro mythical places" included in her automotive guide excerpt, "'Diddy-Wah-Diddy' . . . [is] a magical destination where neither man nor beast had to worry about work or food. Both were magically supplied. They often laughed and dreamed of far-off 'Heaven,' pinning human qualities on its celestial inhabitants." Bordelon, "Zora Neale Hurston," 26. See also Christopher D. Felker, "'Adaptation of Source': Ethnocentricity and 'The Florida Negro,'" in Zora in Florida, ed. Steve Glassman and Kathryn Lee Seidel (Orlando: University of Central Florida Press, 1991), 149. |

| 19. | Bordelon, "Zora Neale Hurston," 17. |

| 20. | McKittrick, Demonic Grounds, xxvi–xxvii. |

| 21. | McKittrick, 5. |