Overview

Kofi Boone describes three towns founded by freed Black people who endeavored to create their own communities. Excerpted from "Enabling Connections to Empower Place: The Carolinas" in Black Landscapes Matter (University of Virginia Press, 2020). Courtesy of the University of Virginia Press.

After the end of the Civil War, recently freed Black people endeavored to create their own communities. During Reconstruction, and with newfound access to political and economic power, Black towns and institutions emerged wherever Black people lived. Before the end of the Civil War, Union soldiers defeating Confederate soldiers attracted emancipated Black people, who settled near Union encampments. In 1865, and immediately after the end of the Civil War, at a former encampment situated across from the town of Tarboro, North Carolina, and within the floodplain of the Tar River, the land was dubbed Freedom Hill. Twenty years later, a Black community elder named Turner Prince purchased the land, and it was renamed Princeville, the first incorporated Black town in America.1Joe A. Mobley, "In the Shadow of White Society: Princeville, a Black Town in North Carolina, 1865–1915," North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 3 (1986): 340–84.

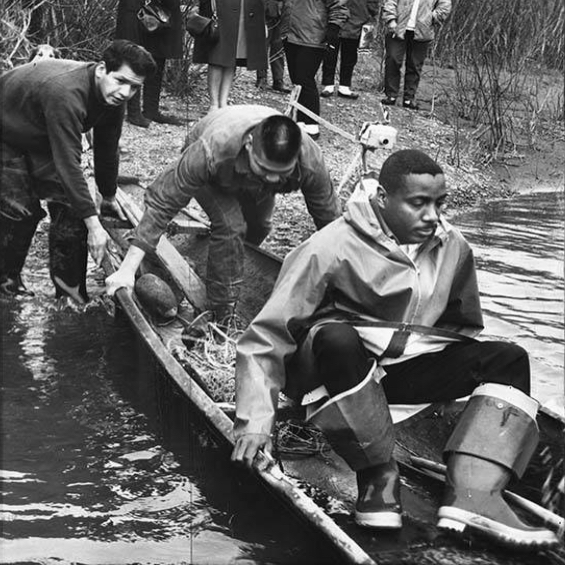

Though Princeville may look like other rural towns in eastern North Carolina, it carries significant histories. Shiloh Landing marks the point along the Tar River where enslaved peopled disembarked into brutal lives of forced labor and captivity. Another riverfront site was later accessed by congregants of local churches, arriving in white-robed processions to perform baptismal ceremonies. Princeville, from its infrastructure to its buildings and landscapes, was self-built by Black residents. Many residents were engaged in the timber and mill industries and located their businesses and homes close to the Tar River, built on stilts to help them survive frequent flooding. Powell Park now marks this area and its emotionally charged history—five major floods inundated the town in the twentieth century. Hurricane Matthew ravaged the town in 2016. Princeville's endurance to rebuild in the face of these devastations has made it especially remarkable.

Princeville was socially as well as environmentally vulnerable, due to racism and the sustained threat of white supremacist violence from nearby communities. Despite these risks, Princeville's population continued to grow, and does so to this day. As an indicator of the place attachment expressed by residents, the town's population increased after the rebuilding periods that followed numerous floods.

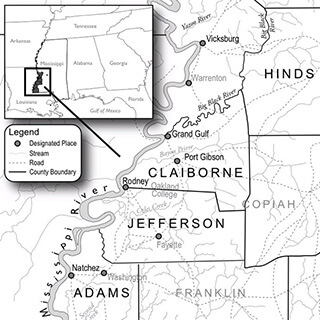

Like Princeville, the town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, also came about by untraditional circumstances. It originated from the enslaved African community of Davis Bend, Mississippi, which was created, in the 1820s, by slave-plantation owner Joseph Davis as a "model" slave community on a plantation. By the standards of America's Peculiar Institution, Davis provided a relatively high level of social, health, and economic care, as well as independence, to Davis Bend's inhabitants. Although still enslaved, residents benefited from dental and health care, opened and ran merchant businesses, and were spared overt domination from overseers. After the Civil War and the collapse of cotton prices, Davis Bend failed, and its residents relocated to the Mississippi Delta bottomlands to found Mound Bayou in 1887. The town earned regional notoriety for its numerous Black owned businesses and organizations, as well as for its tradition of protecting Black people's voting rights amid racial violence. The relative success of the town earned accolades from Booker T. Washington, who called it a model of "thrift and self-government."2Melissa Block, "Here's What's Become of a Historic All-Black Town in the Mississippi Delta," Our Land, National Public Radio, March 8, 2017, www.npr.org/2017/03/08/515814287/heres-whats -become-of-a-historic-all-black-town-in-the-mississippi-delta.

Mound Bayou suffered from declining cotton prices and an uptick in Jim Crow–era oppression. The town distinguished itself, however, by providing safe harbor for Black people seeking modest political and economic independence. Serving as a key organizing ground for the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, Mound Bayou attracted interest from prominent civil rights leaders like Medgar Evers. Regional boycotts, in 1952, of service stations and restrooms refusing to serve Black people were organized in Mound Bayou.3Peter Brown, "Strike City, Mississippi," Anarchy 7, no. 2 (1967): 33–37. And, in 1955, the town served as a safe harbor when Black reporters came to Mississippi to cover Emmett Till's murder trial.4Olive Arnold Adams, Time Bomb: Mississippi Exposed and the Full Story of Emmett Till (Mound Bayou: Mississippi Regional Council of Negro Leadership, 1956). Mound Bayou continues to exist today, though it grapples with the numerous contemporary challenges facing rural southern towns, including population decline and reduced economic opportunities.

Eatonville, Florida, also founded by Black Americans in 1887, represents not only the historical significance of free Black towns but also the contemporary roles Black landscape architects can play in their protection and growth. Eatonville emerged from the lack of human rights protections afforded to Black Americans in the post-Reconstruction era. Named after a white landowner, Joseph Eaton, who was willing to sell land to Black people, the town was originally located on just over one hundred acres in what is now known as Greater Orlando.5United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Eatonville Historic District," September 9, 1997, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/e5fa60c5-551d-41d3-bbef-2a52ff3a7b0b. Eatonville was a fully developed town featuring a bustling business district, churches, and one of the largest schools for Black Americans in the region.

Eatonville rose to national recognition due to the writings of one of its most famous residents, Zora Neale Hurston. Their Eyes Were Watching God, Hurston's groundbreaking Harlem Renaissance novel presenting unvarnished writing about everyday life in the Black South, was set in Eatonville and other nearby Black towns. Later, Club Eaton was a popular performance and layover spot for a wide array of Black entertainers.6United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form."

In the late twentieth century, Eatonville was declining, and Orlando's growth was endangering its remaining historic fabric. Everett L. Fly, a Black architect and landscape architect based in San Antonio, Texas, partnered with Eatonville to generate community development guidelines drawing inspiration from Hurston's literary descriptions of the community's character. Furthermore, Fly partnered with Eatonville to launch a Zora Neale Hurston festival. The annual festival extended the visibility of Eatonville's heritage and provided a revenue source to fund future community improvements. In 1988, Eatonville's Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Eatonville today exists as a town made up of historic pockets intermixed with contemporary development. The town continues to fight for visibility and preservation in the face of Orlando's tourism-driven economic growth.

About the Author

Kofi Boone, FASLA is a professor of landscape architecture at North Carolina State University's College of Design. Boone works at the overlap between landscape architecture and environmental justice with specializations in democratic design, digital media, and interpreting cultural landscapes. He serves on the Board of Directors of the Conservation Network and the Landscape Architecture Foundation.

Recommended Resources

Hahn, Steven. A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Mobley, Joe A. "In the Shadow of White Society: Princeville, a Black Town in North Carolina, 1865–1915." North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 3 (1986): 340–84.

Murrell Taylor, Amy. Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War's Slave Refugee Camps. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Patterson, Tiffany Ruby. "Sex and Color in Eatonville, Florida." In Zora Neale Hurston: And a History of Southern Life, 90–127. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2005.

Schwalm, Leslie Ann. Emancipation's Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Sitton, Thad and James H. Conrad. Freedom Colonies: Independent Black Texans in the Time of Jim Crow. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005.

Tettey-Fio, Eugene. "Black American Geographies: The Historical and Contemporary Distributions of African Americans." In Multicultural Geographies: The Changing Racial/Ethnic Patterns of the United States, edited by John W. Frazier and Florence M. Margai, 31–40. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010.

Web

Mizelle, Richard M., Jr. "Princeville and the Environmental Landscape of Race." Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place, and Community 2 (2016): 16–28. https://editions.lib.umn.edu/openrivers/article/princeville-and-the-environmental-landscape-of-race/.

Padgett, James and Scott Scholl. "The History and Legacy of Eatonville, Florida's Pioneering African-American Town." James Madison Institute. December 6, 2017. https://www.jamesmadison.org/the-history-and-legacy-of-eatonville-floridas-pioneering-african-american-town/.

Ruffin, Herbert G. "Mound Bayou (1887–)." Black Past. January 18, 2007. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mound-bayou-1887/.

"The Side of the River - The Story of Princeville (full movie)." The Language and Life Project. YouTube video, 27:38. April 3, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhRUSZoJ5_Y&t=12s.

Stout, Cathryn. "Why Mound Bayou, MS, and Historic Black Towns Matter." Medium. June 23, 2020. https://medium.com/@cathrynstout/love-letter-to-mound-bayou-ms-and-all-historically-black-towns-eaae7183948d.

Texas Freedom Colonies Project. http://www.thetexasfreedomcoloniesproject.com.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Joe A. Mobley, "In the Shadow of White Society: Princeville, a Black Town in North Carolina, 1865–1915," North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 3 (1986): 340–84. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Melissa Block, "Here's What's Become of a Historic All-Black Town in the Mississippi Delta," Our Land, National Public Radio, March 8, 2017, www.npr.org/2017/03/08/515814287/heres-whats -become-of-a-historic-all-black-town-in-the-mississippi-delta. |

| 3. | Peter Brown, "Strike City, Mississippi," Anarchy 7, no. 2 (1967): 33–37. |

| 4. | Olive Arnold Adams, Time Bomb: Mississippi Exposed and the Full Story of Emmett Till (Mound Bayou: Mississippi Regional Council of Negro Leadership, 1956). |

| 5. | United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Eatonville Historic District," September 9, 1997, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/e5fa60c5-551d-41d3-bbef-2a52ff3a7b0b. |

| 6. | United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form." |