Overview

Stephanie N. Bryan examines the cultural meanings behind opossum hunting and consumption in the US during Jim Crow apartheid—from freed people of African descent for whom these activities represented ecologically rooted foraging skills, economic independence, and household sufficiency; to whites in Georgia and other southern states who turned the opossum into a symbol of racial inferiority as they confronted the reality of Black people transitioning from human property to citizens; and to white male Democrats who cultivated the opossum supper as a theatre for regaining their political stronghold in the wake of Reconstruction and the rise of populism.

Introduction

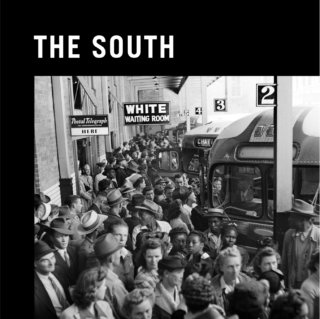

On January 15, 1909, US President-elect William Howard Taft attended a banquet at the Chamber of Commerce along with "the cream of Atlanta and the south's commercial factors, professional men, editors and railroad magnates" where the main course featured a winter trio of roasted opossum, sweet potatoes, and persimmon beer.1"Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge," The New York Times, Jan. 16, 1909, 1. Several months earlier and prior to his election, Taft had become the first Republican candidate to venture into the Democratic "Solid South" during a presidential election.2David Charles Needham, "William Howard Taft, The Negro, and the White South, 1908–1912," (PhD diss., University of Georgia, 1970), 31. The Atlanta banquet represented a continuation of Taft's efforts toward sectional reconciliation as he pledged to "weld into a compact unit the North and the South."3"Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge," 1. The event highlighted the white supremacist solidarities necessary for such political and economic reunification, with his speech elaborating policies that would assure federal appointments would not go to African Americans and that southern metal and cotton products would find commercial opportunities in Far Eastern markets.4William H. Taft, "The Winning of the South," Political Issues and Outlooks: Speeches Delivered Between August, 1908, and February, 1909 (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909), 230–234.

For the prominent white male politicians, businessmen, and other leaders seated at the dining tables, roasted opossum was more than just a show of Gilded Age gustatory extravagance. The food held deep cultural meanings. Since the antebellum era, white males of southern plantation households would occasionally oversee or accompany enslaved people's nighttime opossum hunts, claim their spoils, and then relegate the game's preparation to African American cooks. Drawing on this tradition, a generation of white men with rural upbringings came to see opossum hunts as a means of perpetuating antebellum culture by reinforcing and reinscribing racial lines. They mocked and derided opossums as indicative of negative aspects of African American culture while simultaneously celebrating African Americans as possessing a folk knowledge of hunting, preparing, and cooking opossums.5Psyche Williams-Forson examines similar paradoxes in the case of fried chicken in her chapter "More Than Just the 'Big Piece of Chicken': The Power of Race, Class and Food in American Consciousness," in Food and Culture: A Reader, 3rd ed., Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esterik, eds. (New York: Routledge, 2012): 107–118. See also Williams-Forson Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). In the decades after the Civil War, whites of all social classes increasingly consumed this survival food, now labeling it a "southern delicacy."6This sort of cultural appropriation persisted for over half a century after the Taft banquet, with the women of the Junior League of Charleston, South Carolina, suing Ernest Matthew Mickler, author of White Trash Cooking, in the mid-1980s for lifting what they claimed was their historical recipe for roasted opossum. For a brief discussion of cultural appropriation in this context, see Angela Jill Cooley, "Southern Food Studies: An Overview of Debates in the Field," History Compass 16, no. 10 (2018): 1–9. The dish, known as "'possum and 'taters," was one of many items of "southern cooking," which, as Diane Spivey points out, signified a "Whites Only Cuisine" during Jim Crow.7Diane M. Spivey, "Economics, War, and the Northern Migration of the Southern Black Cook," The Peppers, Crackling, and Knots of Wool Cookbook: The Global Migration of African Cuisine (New York: State University of New York Press, 1999).

Challenged by the economic competition of freed people who sought urban factory jobs and attempted to purchase rural farms, in addition to the political competition of the Populist movement that aimed to unite Blacks and working-class whites, opossum suppers, particularly in Georgia, provided a Democratic theatre in the decades following Reconstruction. At the 1909 Atlanta supper, staged to garner national attention, Taft appealed to Democrats who sought to regain national political strength. As the New York Times reported: "Five hundred eyes watched until he had been served and bountifully served and had taken his first bite of the tempting dish."8"Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge," 1. In the aftermath of this feast, journalist Don Marquis suggested that "the possum, and all the talk back and forth across the festive boards . . . has likely strengthened Mr. Taft's idea that the 'Solid South' is breakable, and that he is the man to break it. . . . How much of the Southern point of view with regard to the negro did Mr. Taft imbibe while eating the possum?"9Don Marquis, "A Glance: Concerning the Possum and the Negro," Uncle Remus's the Home Magazine, March 1909, 26. https://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/digital/collection/printed/id/6450/rec/1.

The opossum's momentary rise to glory parallels the shifting of political power during this era of intensifying apartheid. Whites in Georgia and other southern states turned African American reliance on the opossum as a means of sustenance and source of income into a symbol of racial inferiority. This occurred despite the fact that many subsistence-level whites also sought the opossum as a food source. Glorified opossum consumption complemented practices of Confederate memory-making and white sectional identity.10While scholars and writers have given attention to "southern" foods and foodways since the 1970s and 1980s, the opossum remains largely absent from the historiographical record. Most authors have simply highlighted that this food—along with other game such as raccoons and squirrels—formed an important part of the diets of both white settlers and Black slaves in the antebellum era. Sam Bowers Hilliard, Hog Meat and Hoecake: Food Supply in the Old South, 1810–1860 (1972; repr., Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014), 54; Joe Gray Taylor, Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the South: An Informal History (1982; Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 8; Herbert C. Covey and Dwight Eisnach, What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods and Foodways from the Slave Narratives (Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press, 2009). Literary scholar David S. Shields discusses the appearance of roasted opossum on a hotel menu in "Possum in Wetumpka," Southern Provisions: The Creation & Revival of a Cuisine (Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 143–162. With the emergence of food studies as a field in the 1990s, historians have more rigorously used food to study culture, race, class, gender, and political power.

Geography and Ecology of the Opossum

What was the historical geographic range of the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana)? A mid-1950s article by John Guilday indicates an abundant archeological record of the indigenous marsupial in the Lower and Middle Ohio Valley and in Ohio north to the shore of Lake Erie before European colonization.11John E. Guilday, "The Prehistoric Distribution of the Opossum," Journal of Mammalogy 39 no. 1 (1958): 39–43. An absence of remains reveals that the opossum either did not occur or was uncommon in the Appalachian Plateau of northern West Virginia, western Pennsylvania, and southern New York. Guilday shows that species distribution extended beyond the southeastern United States, even though settlers came to associate the opossum with that section of the country. In The Quadrupeds of North America, John James Audubon writes that the opossum was by no means confined to southern states, particularly during the antebellum period. By 1851 the opossum's range extended north to the Hudson River. Audubon believed that populations would soon occupy southern New York and Long Island "as the living animals are constantly carried there."12John James Audubon and the Rev. John Bachman, The Quadrupeds of North America, vol. II (New York: V. G. Audubon, 1851), 124, https://archive.org/details/b22012436_0002/page/124/mode/1up. In New Jersey and Pennsylvania, opossums were common, but they were more abundant southwardly through North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas, to Mexico. They also existed in Indiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Arkansas, and extended to the Pacific, with some populations in California.13Audubon, Quadrupeds, 125.

The opossum—which is remarkably fecund due to its short gestation period and ability to produce two litters a year in warm climates—was one of the most common small mammals before European colonization in the hardwood forests of the southern Coastal Plain and Piedmont ecoregions, according to environmental historian Timothy Silver.14Timothy Silver, A New Face on the Countryside: Indians, Colonists, and Slaves in South Atlantic Forests, 1500–1800 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 11. Unlike many species of wildlife adapted to these forests, opossums were not negatively impacted by market hunting since their pelts were of low value. The deforestation that accompanied colonial farming practices allowed opossum populations to increase by driving away foxes, wolves, and other predators and by enabling grass and seed-eating mammals, such as rabbits and mice, to proliferate. Audubon's remark that the opossum consumed everything from grain in cornfields to nuts and berries, as well as rodents, rabbits, and hens, indicates that it found plantations and yeoman farms ideal habitats.15Audubon, Quadrupeds, 112.

Many viewed opossums as pests because of their omnivorous eating habits and their ability to destroy food crops. "A 'Possum Sir, is not a critter, but a varmint," remarked an overseer at Belvoir plantation near Pleasant Hill, Alabama, insinuating that the wild animal was not desirable food.16Philip Henry Gosse, Letters From Alabama (U.S.) Chiefly Relating to Natural History (London: Morgan and Chase, 1859), 234, https://archive.org/details/lettersfromalab00goss/page/234/mode/2up. Significantly, English naturalist Philip Henry Gosse, who recorded the overseer's comment while employed as a tutor at Belvoir in 1838, also observed among the neighboring plantations that the meat of both the opossum and raccoon were "scarcely ever eaten by whites, and never in summer." Travel writers, such as Frederick Law Olmsted, offer evidence that whites occasionally ate the meat during the winter. In January 1854, Olmsted recorded the owner of a large plantation in Virginia serving him opossum, which he described as tasting like a "baked sucking-pig."17 Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, With Remarks on Their Economy (New York: Dix and Edwards, 1856), 92, https://archive.org/details/journeyinseaboar00olms/page/92/mode/2up?view=theater. Ex-slave Anderson Furr, who grew up on a plantation in Hall County, Georgia, offers a different perspective of white consumption: "Dey made N*****s go out and hunt 'em and de white folks et 'em. Our mouths would water for some of dat 'possum but it warn't often dey let us have none."18Interview with Anderson Furr in Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration, Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves, vol. IV, Georgia Narratives, Part 1 (Washington, DC: 1941; Project Gutenberg, 2004), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13602/13602-h/13602-h.htm. Furr's recollection suggests that already, in the antebellum era, opossum consumption factored into a display of racial domination.

Hunting methods, such as capturing opossums live to fatten at home and clean out their digestive tracts may have helped to improve the taste of this wild game. Yet, associating opossums with native persimmon fruits enabled a popular imaginary that helped to reduce prejudices against prominent whites who occasionally consumed this lowly scavenger. The American persimmon tree (Diospyros virginiana)—an early invading species in disturbed areas and along forest-pasture boundaries—was common throughout the opossum's range. While Native American stories connected opossums with persimmon fruits, the association was particularly strong in antebellum African American songs and folklore, as well as white settler accounts of opossum hunts.19For examples of opossums eating persimmons, see James Mooney, "The Terrapin's Escape from the Wolves," Myths of the Cherokee (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1902), 278–279, https://archive.org/details/cu31924104080076/page/n7/mode/2up. See also Joel Chandler Harris, "Why Mr. Possum Loves Peace," The Complete Tales of Uncle Remus (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1955), 9. Audubon's illustration of the opossum conveys an ecological association between the plant and animal. Ripe persimmons may have enhanced the flavor of the meat, yet the fruit was not essential to supporting this omnivorous species, which indiscriminately ate plants, insects and animals and opportunistically consumed carrion and trash.

Antebellum Opossum Hunting and Black Culture

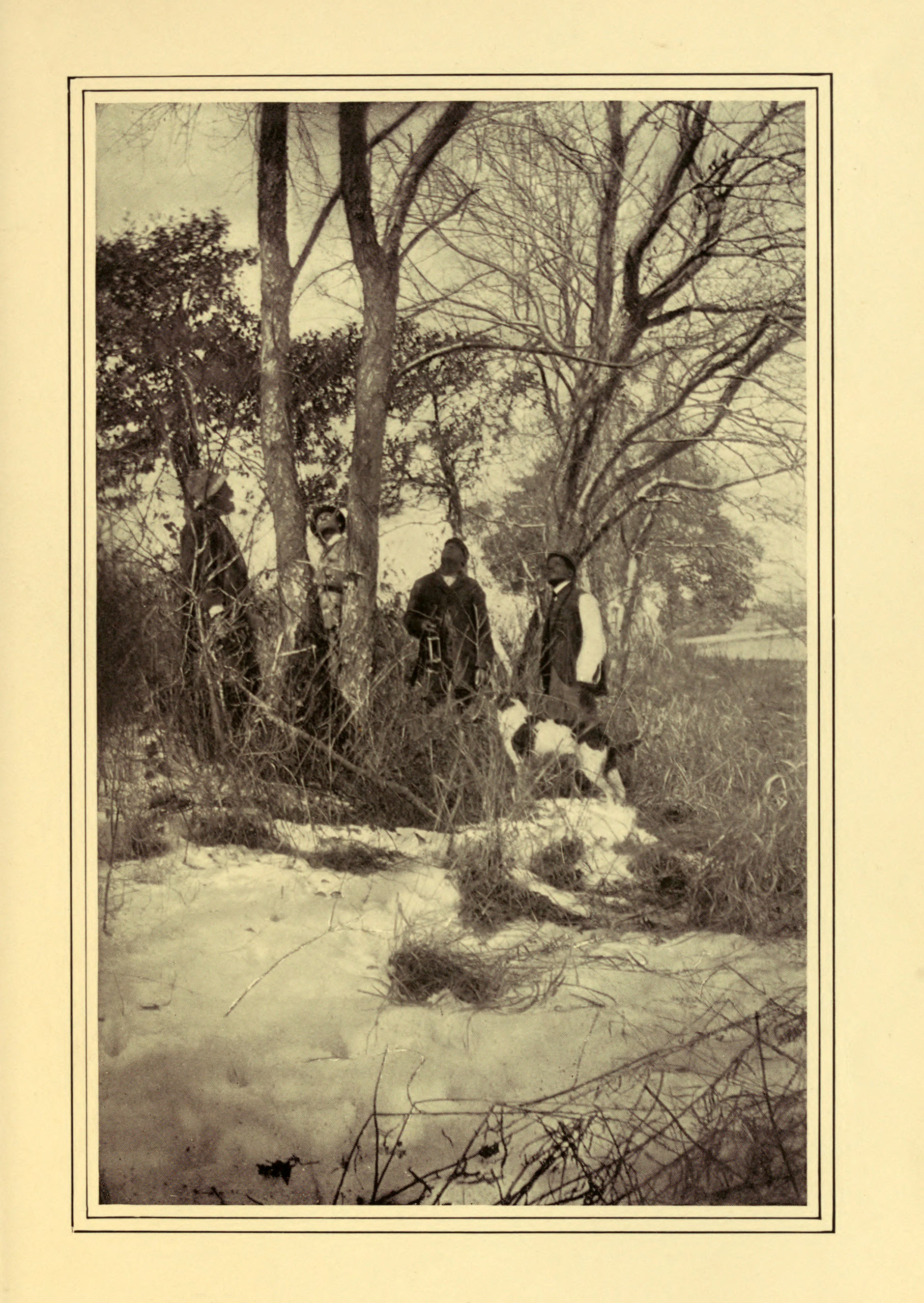

Although opossums were a choice component of the antebellum diets of white small landholders and tenants, primary accounts offer more insight into the connections between this food and enslaved people of African descent.20Subsistence farmers engaged extensively in hunting opossums for food, but early to mid-nineteenth-century written sources emphasize on African American consumption. Along with other small game, opossums were an important source of protein and fat in diets that enslavers kept lean and scarce. Ex-slave Peter Randolph explained that in Virginia many slaves made traps with cut timber, often setting fifteen to twenty of them in the swamps to capture opossums, raccoons, hares, and squirrels.21Peter Randolph, Sketches of Slave Life: Illustrations of the "Peculiar Institution" (Boston, MA: Peter Randolph, 1855), 19–20, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/randol55/randol55.html. Some slaves, however, used trained dogs to tree opossums at night in wooded areas adjoining plantations. Because hunting and setting traps at night did not directly interfere with daytime farm work, some enslavers permitted those they held in bondage to capture small game for supplementary nutrition. Slaves not allowed to go hunting at night had to be more covert. Ex-slave Solomon Northup recalled that in Louisiana, "There are planters whose slaves, for months at a time, have no other meat than such as is obtained in this manner."22Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River, in Louisiana (Buffalo, NY: Derby, Orton, and Mulligan, 1853), 201, https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/northup/northup.html. In interviews for the Works Progress Administration's Federal Writers' Project, the numerous ex-slaves who recollected hunting or eating opossums attest to Northrup's claim that the marsupials were an important meat and that hunger drove consumption of this wild game, often described as greasy and fatty.23See Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration, A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves (Washington, DC, 1941; Project Gutenberg, 2004), https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/13847. A few of the interview references to opossums from the WPA slave narratives are referenced in Stephen Winick's blog "A Possum Crisp and Brown: The Opossum and American Foodways" (Washington DC: Library of Congress, August 15, 2019), https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2019/08/a-possum-crisp-and-brown-the-opossum-and-american-foodways/.

Opossums were more than a survival food for enslaved people. While John Patterson Green, born to emancipated parents in North Carolina, writes that African American opossum consumption "arises not so much from any constitutional partiality on their part, or difference in their tastes [. . .], as from the absence of fresh meats of all kinds," other slaves and freed people expressed the pleasures they experienced from consuming the animal.24John Patterson Green, Recollections of the Inhabitants, Localities, Superstitions and Ku Klux Outrages of the Carolinas (Cleveland, OH: 1880), 181, https://archive.org/details/recollectionsofigree/page/n5/mode/2up]. "The flesh of the coon is palatable," Northrup notes, "but verily there is nothing in all butcherdom so delicious as a roasted 'possum."25Northup, Twelve Years a Slave, 201. The marsupial also enabled enslaved people to access more desirable food. Remembering having "been kept for a long time on corn and potatoes," ex-slave Andrew Jackson of Kentucky revealed that opossums were one of several "expedients to get luxuries."26Andrew Jackson, Narrative and Writings of Andrew Jackson, of Kentucky; Narrated by Himself (Syracuse, NY: Daily and Weekly Star Office, 1847), 27, https://archive.org/details/narrativewriting00jack/page/n27/mode/2up?view=theater&q=pig. Jackson described a scheme of "eating pig for opossum" that entailed obtaining permission to go opossum hunting, skinning several opossums and burying their bodies, killing two pigs and burying their skin and entrails, and then boiling the pork in kettles. The slaves retained the opossum skins as "proof" of the meat's source. Annie Young, from Tennessee, told of a slave caught with a young pig: "Master it may be a shoat now, but it sho was a possum while ago when I put 'im in dis sack."27Interview with Annie Young in The Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration, Slave Narratives, Oklahoma: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves, vol. XIII, Oklahoma Narratives (Washington, DC: 1941; Project Gutenberg, 2007): 359, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20785/20785-h/20785-h.htm. Young's trickster humor suggests a realm of everyday practices that lay beyond the master's grasp.28 Consider Jackson's tale alongside Louis Jordan's popular post-World War II hit song "Ain't Nobody Here But Us Chickens" as discussed in George Lipsitz's Rainbow at Midnight (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 303–310.

Because opossums were important in survivance, they figured prominently into Black culture. Thomas Talley, an African American folklorist whose parents were former slaves, documented antebellum rhymes used for dancing and entertainment, such as the "Possum-La," "'Possum up the Gum Stump," "An Opossum Hunt," and "Shake the Persimmons Down."29Thomas Talley, Negro Folk Rhymes (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1922), 3, 23–24, 34, 233–234. References to some of these songs or rhymes can also be found in ex-slave narratives recorded through the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration. Songs referenced plants, animals, and activities integral to the environments that enslaved people intimately experienced. The deep meanings that the opossum developed through antebellum folklore and foodways—as a connection to the past and an avenue to the future—would make it all the more significant when southern whites tried to claim an exclusivity of this food during Jim Crow.

Postbellum Opossum Hunting and White Supremacy

After the Civil War, hunting, selling, and consuming opossums remained significant among many African Americans. As formerly enslaved people sought to carve out autonomous livelihoods, opossum consumption represented ecologically rooted foraging skills, economic independence, and household sufficiency. Newspapers began to relay impressive—if not exaggerated—hunting accounts. An editor, for example, remarked on New Year's Day 1880 that a Black hunter in Anderson County, South Carolina had caught 127 opossums since the previous fall.30"South Carolina News," Yorkville (SC) Enquirer, Jan. 1, 1880, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026925/1880-01-01/ed-1/seq-2/.Although generally considered a male activity, there were exceptions, such as a Black woman's catching fifteen opossums in Muscogee County, Georgia, in 1877.31"Foraging on our Exchanges," The LaGrange (GA) Reporter, Oct. 11, 1877, 2, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn82015287/1877-10-11/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=10%2F11%2F1877&city=LaGrange&date2=10%2F11%2F1877&words=&searchType=advanced¬text=&index=2&sequence=0&proxdistance=5&rows=12&ortext=&proxtext=&andtext=&page=1.

Enslavers may have tolerated—and on occasion, celebrated—antebellum opossum hunting. Yet, when these same men lost control over their labor force and struggled to maintain their livelihoods after the war, Black opossum hunts signaled an infringement on white supremacy. Whites sought to assert control over African American hunting and foraging practices. Attending opossum hunts with their former slaves provided one way for whites to flex their power. Opossum bounties were another. Depicting autonomous Black hunts as pathological and wasteful, one Atlantan wrote: "But we are wandering among the black jocks," adding that an opossum bounty will "protect negro labor and revive their languid interest in the best government."32"Possums and Protection," Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Sept. 20, 1882, 4. Because opossums destroyed crops and raided chicken houses, bounties gave landowners a way to protect their capital from pests and predators.33There may have been other motives behind paying African Americans to hunt opossums. By paying freed people to hunt opossums, former slave owners attempted to assert their authority over Black hunting, which they framed as an idle diversion from necessary farm work.34Scott Giltner, Hunting and Fishing in the New South: Black Labor and White Leisure after the Civil War (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 28.

For white men who had grown up on plantations, postbellum Black opossum hunting could evoke conflicting feelings. Sometimes the activity signaled a threat to white supremacy, while other times it featured in an imagined "South." While the Ramapough Mountain Indians of New Jersey and New York engaged in hunting opossums, a New York Times correspondent asserted in 1886 that they were "not such picturesque35"Picturesque" appears frequently in late-nineteenth century writing describing opossum hunting throughout the southern states. The term was rooted in eighteenth-century British landscape design, but travel writers, such as William Bartram, later used it to describe an attractive or pleasing scene. See "Picturesque," (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, last edited 2021), https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Picturesque. hunters as their brethren of the south" because, instead of using hunting dogs, they relied on guns and deadfall traps (even though slaves and freed people in the southern states also used guns and traps).36"Hunting the Possum," Buffalo (NY) Commercial, Sep. 4, 1886, 1; "Hunting the Opossum. A Place Where He Is Found North of Mason and Dixon's Line," Wood County Reporter (Grand Rapids, WI), Sep. 23, 1886, 6, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85033078/1886-09-23/ed-1/seq-6/. Stereotypical depictions of place and race formed around the native marsupial. "No one ever located the opossum hunt anywhere but in the gum swamps or among the persimmon trees of the south," the correspondent wrote in popular racist imagery, "where they are ever associated with the spectacle of the bulging-eyed and expectant darky carrying aloft his flaming pine-knot torch, while his lean and lanky dog leads him to the tree where the much prized possum has sought refuge." A racist "plantation song" suggests a chaotic scene:

Afore de n****r could come down de tree would mostly fall—

Then smack among the dogs would light de possum n*g and all,

De dogs would pitch upon 'em both and most tar dem in half,

Old Marster he would stand aside and kill hisself wid laugh.37"Possum Hunting—A Song," Fairfield Herald (Winnsboro, SC), Mar. 12, 1873, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026923/1873-03-12/ed-1/seq-1/.

Whites reinforced their belief in Black inferiority by turning this strenuous and risky nighttime activity of Black survival and economic autonomy into a "picturesque" scene and humorous "spectacle." Such depictions omitted the horrific violence of slavery and Jim Crow, as well as the ecological destruction wrought by cotton, tobacco, and other monocrops that increasingly shaped foodways and contributed to the overhunting of wild game.

For some white men who grew up on plantations or farms in the southern states, opossum hunting evoked Confederate nostalgia. Drawing on tropes portraying Blacks as ineligible for freedom or citizenship, an Atlanta Constitution editor wrote: "Memory yet dwells with peculiar emotions of pleasure upon those glorious old hunts we used to take in by-gone days before Sambo had been transformed into a fifteenth amendment."39"The Opossum," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Dec. 3, 1874, 1. A columnist from Natchitoches, Louisiana, suggested: "It reminds one of the lost days ante bellum to speak of such a delicious treat as cold possum and tater on a winter's night."40"Possum and Tater," The People's Vindicator (Natchitoches, LA), Sept. 15, 1877, 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038558/1877-09-15/ed-1/seq-3/. As it fed nostalgic memory-making, opossum hunting was more than a way of reenacting a past more often imagined than real; it represented a future where whites could retain aspects of their southern sectional identity. Another Atlanta Constitution writer offered his grandiloquent rumination:

There are some customs that even the reconstruction laws failed to disestablish and some of them are intimately connected with the opossum. The opossum still survives the war and all the sectional strife and we have sometimes hoped that the day would come when [. . .] it might become the basis, if not the emblem, of North American fraternity.41"The Premature 'Possum," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Aug. 6, 1882, 4.

A white brotherhood, binding the war-torn sections through the hunting and eating of opossums appealed to an apartheid appetite. As Kyla Wazana Tompkins observes, "acts of eating cultivate political subjects by fusing the social with the biological, by imaginatively shaping the matter we experience as body and self."42Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the 19th Century (New York: New York University Press, 2012), 1. The opossum supper—a social occasion where white men came together to consume Black labor—served as a signifier of racist solidarity in the decades after the Civil War.

Cultural Appropriation, Neo-Confederates, and Urban Game Markets

Following Reconstruction, Blacks continued to hunt and eat opossums as they had for generations, as did many rural white farmers. In addition, the ascendant white political leadership ("Redeemers") who were attempting to reclaim racial command over Black labor and southern land, increasingly and publicly engaged in these activities. A plantation imaginary filled with adventuresome opossum hunts contributed to the appeal and surge of opossum suppers among white men, who had grown up on plantations or farms but were now confronting the reality of Black people transitioning from human property to citizens. They scrambled to find and re-hash tropes to narrate white supremacy and reassert racial power. Beyond overseeing Black opossum hunts, these men claimed the opossum as a rightful inheritance while depicting Black consumption as deviant. They drew on longstanding racist tropes that cast Blacks as possessing an excessive animality and fondness for opossums, while situating their own opossum consumption as appropriate, measured, and tastefully respectable. Concurrently with terroristic attempts to overthrow Black freedom struggles during Reconstruction, white men within the Democratic party cultivated the opossum supper as a theatre for leadership rites and as a site for framing anti-democratic contentions and racist tactics as legitimate, authentic, and appropriate.

In the 1870s, opossum supper announcements became common in newspapers of southeastern states and occasionally in some northeastern and midwestern ones where freed people had begun to migrate. Early on, these events involved people of different socioeconomic classes and racial or ethnic backgrounds and occurred for a variety of reasons—from political gatherings to church fundraisers and more intimate domestic occasions. With time, Democratic politicians turned the opossum supper into a social event expressive of white men's solidarity.

With the rebuilding and growth of towns into small cities after the Civil War, markets for selling opossums and other game grew. A shift in urban demographics also contributed to growing markets, with both Black and white consumers. In Atlanta, where the proportion of the city's Black population had more than doubled between 1860 and 1870, a notable opossum trade developed.43Tera Hunter, To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 21. Atlanta's opossum market stood out with high demands among restaurant keepers, grocers, and commissioners. The grocery firm Messrs. Hambright & Co., for example, opened a wholesale trade, receiving "an invoice of live opossums nearly every day, sometimes as many as sixty at a time" to distribute to retailers in 1874.44"The Opossum," 1. African American Howard Horton drove daily through the city's streets in a wagon with live and dressed animals from the country.45"The Opossum," 1. Known as the city's "great possum cleaner," Horton, a Republican politician, estimated in 1882 that he had dressed approximately two hundred opossums a season, totaling several thousand in his lifetime.46"Howard Horton on Possums," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Oct. 24, 1885, 7. Among his clients were white doctors and businessmen, along with politicians, such as Democratic mayor George Hillyer and governor Alfred Colquitt, who vehemently opposed Republican Reconstruction policies.

The large influx of rural whites and freed people into southern cities fueled the growth of urban game markets throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1888, the marsupial had "arisen to a very important place in the commercial world" with one Atlanta commissioner handling three hundred of them a month and reportedly earning about $500.47"'Possum and 'Tater. Georgia Gourmets Now Reveling in the Chief Delight of the Year," reprinted from the Atlanta (GA) Journal in the Sun (New York, NY), Oct. 28, 1888, 5, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1888-10-28/ed-1/seq-5/. This "country animal has been a part of the south as long as there has been any south," the author asserted. The next year wholesale grocer J.C. McMillan & Co., located on Marietta Street in Atlanta, had begun keeping 160 opossums in a room, where they were "fed on slops just like a pig" for two weeks before being butchered for the table.48"A Horde of 'Possums. The Animals are Kept in a Room on Marietta Street," The Morning News (Savannah, GA), Dec. 11, 1888, 6, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn86063034/1888-12-11/ed-1/seq-6/. While purifying the digestive tracts of these omnivorous animals helped make their meat more suitable for city consumers, so did the removal of grease and fat through distinct roasting techniques.49Richard Malcolm Johnston's government report indicates some of these class differences. In it, he wrote, "Southerners regard it of all meats the least indigestible, and but for its superabundant fat it would appear more frequently on tables of the whites. In some houses this superfluity was disposed of by placing a layer or more of oak or hickory sticks to the height of 3 or 4 inches at the bottom of the oven, and upon the latticework thus made laying the opossum. By such mode much of the oil was deposited on the bottom. The negro, when cooking for himself, never resorts to these measures, but takes his favorite as he is, indeed preferring him with all his imperfections on his head." Richard Malcolm Johnston, "Opossum Hunting Before the War: From the reports of the Bureau of Education," reprinted in Game Laws in Brief and Woodcraft Magazine 1, no. 1 (New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, April 1899), 111, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433082123633&view=1up&seq=127&skin=2021.

Enterprising farmers found commercial potential in raising opossums. Their efforts joined other uncommon industries labeled as "freak farms."50For a description of different types of "freak farms," see, "Freak Farms a Big Profit to Their Owners," Evening Star (Washington, DC), Aug. 27, 1911, 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1911-08-27/ed-1/seq-48/; see also Liberty Hyde Bailey, "The Collapse of Freak Farming," Country Life in America no. 4 (May 1903): 14–16, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015028160110&view=1up&seq=26&skin=2021. Thomas Chancey started one of the first opossum "ranches" near Hawkinsville, Georgia, in 1884.51"Opossum Farm Down South," Carroll Free Press (Carrolton, GA), June 20, 1884, 4, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn89053126/1884-06-20/ed-1/seq-4/. Soon after, another began in Spartanburg, South Carolina.52The Anderson (SC) Intelligencer, May 14, 1885, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026965/1885-05-14/ed-1/seq-2/. Arthur Pritchard's opossum farm in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, attracted visitors in 1889.53"A Possum Farm," The Democrat (Scotland Neck, NC), Dec. 5, 1889, 1, https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073907/1889-12-05/ed-1/seq-1/. With opossums growing in demand and commanding higher prices, commercial enterprises spread to other parts of the country, including Colonel Isaac Davis's opossum farm in Ohio, in 1889;54"The Opossum Farm," Democratic Northwest (Napoleon, OH), Dec. 19, 1889, 4, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84028296/1889-12-19/ed-1/seq-4/. John Rand's ranch in Louisiana, in 1892;55"State News," St. Landry Clarion (Opelousas, LA), May 7, 1892, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88064250/1892-05-07/ed-1/seq-1/. an English farmer, H.I. Twigg's establishment in Kentucky, in 1896;56"Two Queer Farms," Hopkinsville Kentuckian, June 19, 1896, 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069395/1896-06-19/ed-1/seq-3/. an unidentified Texas man who had 200 acres of enclosed persimmon trees and muscadine vines in 1899;57"About Texas Crops," Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore, OK), June 14, 1899, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042303/1899-06-14/ed-1/seq-1/. James Hart's opossum breeding project in Indiana, in 1900;58"From Saturday's Daily," Marshall County Independent (Plymouth, IN), Mar. 23, 1900, 5, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87056251/1900-03-23/ed-1/seq-5/. and governor John Spark's Alamo cattle ranch in Nevada, which received a shipment of opossums from Florida, in 1903.59"Sparks' Possum Ranch," Morning Appeal (Carson City, NV), Nov. 25, 1903, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86076999/1903-11-25/ed-1/seq-2/.

While opossum farms existed in several states, the most extensive venture was William Throckmorton's ten-acre persimmon grove in Griffin, Georgia, where "over 700 possums were together so thick that the ground could not be seen between them."60E.W.B., "A 'Possum Farm," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, June 23, 1889, 10. Of the five hundred opossums Throckmorton shipped in late 1889, some went dressed to cities throughout the state, while most went alive by rail to Washington, DC. Politicians consumed opossums at upscale establishments such as L.B. Folsom's restaurant61Known as the "Reading Room" for keeping newspapers, periodicals, and magazines for patrons, Folsom's became "the meeting place of men famous in Georgia affairs." Notable patrons included politician and former Confederate general Robert Toombs; former Atlanta mayor Captain J.W. English; and Atlanta Constitution editors Henry Grady and Evan Howell. "Folsom's Changes Hands," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Oct. 1, 1911, D7. in Atlanta, which reportedly was butchering a hundred of the animals monthly.62"'Possum and 'Tater. Georgia Gourmets Now Reveling in the Chief Delight of the Year," https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1888-10-28/ed-1/seq-5/. Shipments by enterprising individuals such as Throckmorton fulfilled requests by southern congressmen. Georgia Democratic congressmen John Stewart of Griffin and George Barnes of Augusta were "perhaps the most inveterate 'possum eaters in Congress," according to the Atlanta Constitution.63This story gained significant attention. E.W.B., "A 'Possum Farm," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, June 23, 1889, 10. The congressmen's consumption of opossum marked a shift from the antebellum era when prominent whites would have seldom consumed this survival food.

Opossum Stories, Politics, and Populism

As they sought to legitimize public opossum consumption for themselves, whites engaged in an ongoing dance between accounts of their own tasteful meals of opossum meat and narratives portraying opossum eating among Blacks as a sign of racial and cultural inferiority. Racist stories about opossums and other foods that represented African American social, cultural, and economic autonomy proliferated in the wake of Democratic organizing. In 1868, an opossum trickster story surfaced in a speech at a rally in Walhalla, South Carolina, for Democratic presidential and vice-presidential candidates Horatio Seymour and Francis Blair, Jr.64"Thunder in the Mountains," Charleston (SC) Daily News, Sept. 22, 1868, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026994/1868-09-22/ed-1/seq-1/. Drawing on a popular tale that newspapers circulated for over four decades after the Civil War, Greenville journalist Robert McKay conveyed a fictional account of an old hunter who had caught an opossum and fell asleep while roasting it. Another character ate it and deceived the sleeping hunter by leaving the bones in his hands and greasing his mouth so that when he awoke, he believed he had eaten it despite still feeling empty. Rooted in the prewar era, this trickster story was one of the few that depicted a slave stealing from another.65Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 131. The account sent a message that Blacks could not be trusted, while also asserting that Black people were too unintelligent to know when they had been duped. For McKay, the story showed that freed Blacks "could be made to believe anything. If they would not listen to good advice," he insisted, "they must go on until they found everything eaten up, and then they would be devilish hungry still."66"Thunder in the Mountains," https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026994/1868-09-22/ed-1/seq-1/. The story depicted Blacks as unintelligent and gullible, and incapable of controlling their insatiable appetites without white authority.

Decades later, white Democrats deployed opossum politics by portraying Blacks as chiefly motivated by appetites. In 1890, a Washington Post writer reiterated McKay's earlier claim that Black opossum consumption revealed animal instincts and inherent political naiveté. However, while McKay had insisted that Blacks were gullible, the Post article added to the narrative by suggesting that the food could be used to garner Black votes. Alexander Dockery, a Democratic member of the US House, had taken "two of his trusted lieutenants some days before the last election and made a trip through the 'Black Belt' [cotton-growing area with large populations of ex-slaves], giving out mysterious invitations to the colored voters to meet" for a supper in Missouri. While the 150 Blacks allegedly in attendance dined on opossums and raccoons, Dockery recited a political speech.67"Dockery's Coon Supper," Washington (DC) Post, Nov. 24, 1890, 2. The takeaway of the story was that, by using game stereotypically associated with ex-slaves, unsavory political actors could easily attract Black Republican voters and deceive them with political promises.68"Thunder in the Mountains," https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026994/1868-09-22/ed-1/seq-1/. Similar stories proliferated, leading a Washington Evening Star writer to later reminisce that opossum suppers were "great vote-getters in the south."69"'Possum for President in Southern Style," Evening Star (Washington, DC), Dec. 22, 1907, 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1907-12-22/ed-1/seq-51/. Notably, Dockery's story in 1890 appeared shortly before Democrats began to disenfranchise Blacks by law.

The timing coincides with the rise of the Populist Party, which threatened Democratic Redeemers as it sought, in its beginnings, to unite Blacks and poor whites. Populism was concentrated in the agrarian southern, southwestern, and midwestern states. Its leaders, as one historian has written, "advocated radical changes in the monetary system, regulation of the railroads, and land control as the means by which economic fairness could be assured for all oppressed people."70Sarah A. Soule, "Populism and Black Lynching in Georgia, 1890–1900," Social Forces 71, no. 2 (1992): 395–421. In 1890, Thomas E. Watson of Thomson, Georgia, campaigned on the Farmers' Alliance platform and won a seat in the US House of Representatives. Soon after, he emerged as the state's leading Populist politician and his party threatened Democrats with the possibility of dividing the white vote.

To maintain the existing class and political structure, white Democrats turned to tactics of disenfranchisement and terror against Blacks and poor whites. "The Democrats resorted to murder and beatings to drive blacks away from the Populists," explains historian Charles Postel, adding that Populists also "used terror and intimidation to prevent blacks from voting for Democrats."71Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 196. Historian C. Vann Woodward points out the high degree of election fraud, noting that there was no way to prevent "wholesale repeating, bribery, ballot-box stuffing, voting of minors, and intimidation" at the polls.72C. Vann Woodward, Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1963), 208. Moreover, Black plantation hands and laborers were hauled by wagon loads and forced to vote the Democratic ticket, some doing so multiple times. Watson lost his 1892 bid for reelection to Congress to Democrat James C. C. Black of Augusta and was defeated again in 1894. Widespread violence and fraud shaped these election outcomes.

Georgia's Opossum Regime

While opossum suppers had grown in popularity throughout the southeastern US in the wake of Emancipation, it is not incidental that Georgia—the last of the former Confederate states to be readmitted into the Union (1870)—would become the spiritual center of these events within a few decades. In the 1890s, cotton-growing states had fallen into an economic depression as prices plummeted and farmers' debts increased.73Steven Hahn, The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). Populism created political competition. Freedmen, who had begun seeking factory jobs in cities and attempting to purchase farms in the country, represented economic competition. White racism and lynching intensified.74 Jack Bloom, Class, Race and the Civil Rights Movements: The Changing Political Economy of Southern Racism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987). Georgia had the second highest number of lynchings from 1890–1900.75Susan Olzak, "The Political Context of Competition: Lynching and Urban Racial Violence, 1882–1914," Social Forces 69, no. 2 (1990): 395–421; George Milton, et al., Lynchings and What They Mean: General Findings of the Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching (Atlanta, GA: The Commission, 1932). Statewide Black voter turnout declined from 55% in 1876 to less than 10% after 1890.76J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One Party South, 1880–1910 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974). Lynchings and other forms of vigilante violence helped to ensure a Democratic takeover of government.

Opossum suppers became an important stage on which political actors could deploy new strategies and solidify networks of accomplices. Beginning in 1894, Colonel Harry Fisher—"railroad man, fertilizer magnate, friend of corporations"—commenced the political opossum suppers of Newnan, Georgia, to advance the Democratic ticket.77"Possum and Politicians: Many Invitations Have Been Sent Out to Newnan's Possum Supper," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Dec. 28, 1897, 5, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063034/1897-12-28/ed-1/seq-2/. See also "Politicians to Eat 'Possum. The Supper at Newnan to Be a Unique Affair," The Morning News News (Savannah, GA), Dec. 28, 1897, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063034/1897-12-28/ed-1/seq-2/. Located about forty miles southwest of Atlanta where many in-state attendees traveled from, Newnan had escaped destruction during the Civil War. Its supper became an annual event, sending out over six hundred invitations "to men of prominence, both inside and outside" of the state. Politicians gathered in anticipation of the official Democratic convention and, while eating opossum, pre-determined the roster of officials for high-ranking positions.

It wasn't long before outside observers began to recognize that the political sway of the Newnan opossum suppers extended beyond southern states. On January 1, 1898, northern newspapers warned of sinister plans circulating "under the cover of savory vapors":

To these feasts are bidden men who have controlled the destinies of the State for years—shrewd politicians, who are anxious to strengthen their influence, statesmen, who gladly seize the opportunity to keep politically in touch with the elect of the State, and persons of a purely convivial nature, who are useful in lending an airy background to the political scheming which is bound to take place under the cover of savory vapors which ascend from the smoking 'possum.78"A 'Possum Supper," Baltimore (MD) Sun, Jan. 1, 1898, 1. For a similar version of this article, see "'Possum and 'Taters," The World (New York, NY), Jan. 1, 1898, 5.

Nearly a decade later, editor, politician, and defender of lynching John Temple Graves reminisced about Georgia's political "'possum regime," which had come to encompass the two-term governorships of Democrats William Y. Atkinson (1894–1898) and Joseph M. Terrell (1902–1907).79John Temple Graves, "The 'Possum Governors" of Georgia," reprinted from the New York American in The Herald and Advertiser (Newnan, GA), Jan. 15, 1909, 1, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn89053456/1909-01-15/ed-1/seq-1/. Atkinson won by a narrow margin in 1894 against Populist candidate Judge James K. Hines and regained reelection in 1896 over another Populist candidate, Seaborn Wright.80James F. Cook, "William Yates Atkinson 1894–1898," The Governors of Georgia, 1754–2004, 3rd ed. (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005), 181–184. Benefiting from white terror, voter suppression, and fraud, Atkinson ended the threat Populists posed to Democrats in statewide elections.81The 1896 presidential election would further fracture the Populist party across the southern states. Some Populists who supported a fusion with Democrats nominated Tom Watson as the vice-presidential candidate alongside William Jennings Bryan for president. The Democratic National Convention also nominated Bryan, but with Democrat Arthur Sewall as his running mate, both of whom appeared on the Silver Party ticket. Conservative Democrats who disagreed with Bryan's stance on bimetallism and free silver abandoned the party to form the National Democratic Party and instead nominated Senator John Palmer along with his running-mate Simon Bolivar Buckner. With the country experiencing an ongoing economic depression under Democratic President Grover Cleveland, Republican presidential and vice-presidential nominees William McKinley and Garret Hobart, who stood for protectionism and the gold standard, defeated Bryan.

In his capacity of Speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives, Atkinson "had performed countless favors, helping many of his friends gain appointments as solicitors-general and judges of the circuit courts," explains historian Barton Shaw, adding that "Such men eagerly endorsed Atkinson's candidacy, and he also had support in Atlanta's traditional rivals, Augusta, Macon, and Columbus."82Barton C. Shaw, The Wool-Hat Boys: Georgia's Populist Party (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984), 111. Through these favors, Atkinson "was able to depose the old Bourbon ring perfected by Henry Grady and the Triumvirate," while forging a new legislative ring.83Shaw, The Wool-Hat Boys, 126. His initial gubernatorial campaign against Confederate veteran General Clement Evans was a "coup d'état" that "allowed younger Democrats to take control of the party."84Shaw, The Wool-Hat Boys, 112.

The complexity and behind-the-scenes maneuvering of numerous political factions during this period cast a cloud over why conservative Democrat Allen D. Candler (1898–1902) or Progressive Hoke Smith (1907–1909, 1911) were not considered part of the conspiracy, although it may relate to their efforts to restrict the power of the state railroad commission.85Cook, "Allen Daniel Candler 1898–1902," "Hoke Smith 1907–1909, 1911," Joseph Mackey Brown 1909–1911, 1912–1913," The Governors of Georgia, 185–188; 192–195. For more on Candler claiming to not be part of the "'possum regime" see "Candler on 'Possum Supper," Americus (GA) Times-Recorder, Jan. 14, 1898, 3, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn89053207/1898-01-14/ed-1/seq-3/. Editor Graves offers some insight that Georgia's "'possum regime' was in large measure a railroad regime, and that under it corporations expect the fullness and the fatness which distinguished the adipose of the Georgia 'possum."86Graves, "The 'Possum Governors' of Georgia," https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn89053456/1909-01-15/ed-1/seq-1/. Accordingly, capital interests played an important role in the "booming" of certain politicians over others at events such as the Newnan opossum suppers. Barton Shaw explains the monetary benefits gained by those whom legislators appointed: "Solicitors were partly paid in fees, and citizens who could pay the highest price often found the state's charges against them dropped or at least reduced. Judges not only received handsome salaries, but were in excellent positions for advancement. The convict leaseholders always smiled upon those who helped keep up the supply of prisoners. With such support, many judges soon found themselves holding seats in Congress."87Shaw, The Wool-Hat Boys, 125.

The motives behind the Newnan opossum suppers were multifaceted, serving both the personal and collective interests of those in attendance. While they had a dominant Democratic component, occasional guests from other factions superficially presented images of reunion and reconciliation. Honorable George Peck of Chicago, a well-known railroad man who had served as a federal soldier, "referred to himself as the only yankee in the room" in a speech at the function on New Year's Eve 1897.88"'Possum Aftermath," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Jan. 2, 1898, 6. "A good deal of fun had been poked at him during the evening because of republicanism" and Confederate General Clement Evans, who attended the event, claimed to have made him "eat Georgia 'possum until he quit and surrendered and went over to the other side."89"Possum Aftermath;" "'Possum and Politics Wrestle for Supremacy Down at Newnan's Feast," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Jan. 1, 1898, 5. Although Atlanta Constitution columnist Bill Arp concluded after the event that "a politician will eat anything for office," eating opossum had developed a deeper meaning for prominent white men attending these events, signifying an economic and political alliance, as well as a racial one.90"'Possums and Politics," Watchman and Southron (Sumter, SC), Jan. 26, 1898, 2. "Bill Arp," was a pseudonym for politician Charles Henry Smith: https://evhsonline.org/bartow-history/people/charles-henry-smith-bill-arp-great-american-humorist-writer. Newspapers reported that the 1897 event included a diorama behind the toastmaster's chair comprised of a real persimmon tree, six live opossums, an actual baying opossum dog, and "old Uncle 'Cotton' See, an anxious-looking aged negro with white hair and a 'possum appetite in keeping with his surroundings" of white governors, secretaries of state, attorney generals, judges, and other high officials discussing politics over the feast.91"And Politics for Down at Newnan's Feast to the Governor," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Jan. 1, 1898, 5. This nostalgic scene provided a visual display of white power, delineating the rightful place of Blacks not as consumers of opossum, but as providers, cooks, and servers of it.

While Newnan's political opossum suppers were widely publicized in local and national newspapers, the public's attention soon shifted in 1899 to the horrific mob lynching of Sam Hose—a Black man who was bound, tortured, castrated, and set on fire in front of more than four thousand spectators.92For a detailed analysis of this event, see Edwin T. Arnold, What Virtue There Is in Fire: Cultural Memory and the Lynching of Sam Hose (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012). Chicago detective Louis P. Le Vin, whom activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett hired to investigate the lynching, concluded, "The real purpose of these savage demonstrations is to teach the Negro that in the South he has no rights that the law will enforce. Samuel Hose was burned to teach the Negroes that no matter what a white man does to them, they must not resist."93Ida B. Wells-Barnett, "Lynch Law in Georgia," (Chicago, IL: Chicago Colored Citizens, 1899), https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t1612/?st=text&r=0.267,0.55,0.665,0.719,0. William Atkinson, who had moved to Coweta County to practice law following his second term as governor, spoke out to the mob from the city jail in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent Hose's lynching. 94For more on Atkinson's actions and possible motives, see Arnold, What Virtue There Is in Fire, 98–102. As governor, Atkinson had tried on numerous occasions to get the General Assembly to pass his anti-lynching bills. Because he vehemently opposed the lawlessness of mobs and proposed other solutions such as public executions, the anti-lynching stance of Atkinson and other Democrats cannot be equated with racial justice.95Arnold, What Virtue There Is in Fire, 99–100. The Sam Hose lynching led a writer from Thomasville, located near the state's southern border, to comment that Newnan's "reputation no longer rests on possum suppers."96The Daily-Times Enterprise (Thomasville, GA), May 9, 1899, 2, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn88054087/1899-05-09/ed-1/seq-2/. Yet, to some extent the town's reputation did continue to rest on its opossum suppers as the political scheming that occurred at them played a role in the election of governors and other influential white men who disenfranchised Black citizens and worked to maintain the state's Democratic stranglehold.

Symbolic Separations and the Taft Banquet in Atlanta

If white Democrats were responsible for the publicized and politicized opossum suppers in southern states such as Georgia, Blacks gained attention for hosting their own events in other parts of the country.97For several examples of newspaper accounts highlighting these events, see "New Year Festivities at Crowe's Hall," Alton (IL) Evening Telegraph, Jan. 3, 1894, 9; "Lovers of 'Possums: Indianapolis Epicures Who Fancy the Toothsome Dish," The Indianapolis (IN) Journal, Part Two, Dec. 28, 1902, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015679/1902-12-28/ed-1/seq-13/; "Oh, Carve Dat 'Possum: First Annual Banquet of 'Possum Club a Splendid Success," Durant Weekly News (Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, OK), Dec. 8, 1905, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015679/1902-12-28/ed-1/seq-13/; "Happenings Condensed," Palestine (TX) Daily Herald, Nov. 29, 1905, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86090383/1905-11-29/ed-1/seq-2/; "Local Briefs," Deseret Evening News (Great Salt Lake City, UT), Feb. 18, 1902, 8, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045555/1902-02-18/ed-1/seq-8/; "Another 'Possum Supper," Morning World Herald (Omaha, NE), Nov. 18, 1902, 2; "That 'Possum Supper," The Anaconda (MT) Standard, Dec. 31, 1901, 9; "A Possum Supper," Grand Forks (ND) Daily Herald, Jan. 9, 1903, 4; "'Possum Supper with Hoe Cake Trimmin's; Janitor Duncan and His Colored Friends are Preparing a Big Treat for Office Holders and Others," Colorado Springs (CO) Gazette, Dec. 9, 1903, 3. Migrating Black populations continued to host opossum suppers in northern and western states, keeping the tradition popular into the early twentieth century. No doubt these individuals were aware of the strong association that opossum suppers had developed among southern Democrats, as well as the longstanding stereotypes aimed at destroying the personal and collective power of Blacks. Their actions can be understood as what Psyche Williams-Forson describes—in the case of Black women redefining fried chicken—as a refusal "to allow the wider American culture to dictate what represents their expressive culture and thereby what represents blackness."98Williams-Forson, "More than Just a 'Big Piece of Chicken'," 107–118, 343.

In 1901, Alfred King held an opossum supper at his Illinois home for the white members with whom he had served on a grand jury, along with other guests including the state attorney, sheriff, circuit clerk, and chief of police. "This is the first time," King announced, "that a grand jury in Macon county ever dined with a colored man, but the world do[es] move," indicating a shift in race relations.99"'Possum Supper. First Grand Jury to Dine with Colored Man," The Daily Review (Decatur, IL), Nov. 22, 1901. The elaborate menu—which included a course of oyster soup with celery and crackers, as well as main dishes of roasted turkey, baked opossum, mashed and sweet potatoes, corn, slaw, cranberries, white and corn bread, in addition to lemon and pumpkin pie, various fruits, ice cream and cake, and coffee for dessert—was not unlike that of an opossum banquet hosted by southern white Democrats.100"'Possum Supper," The Daily Review (Decatur, IL), Nov. 22, 1901.

A few years later, in 1903, ex-slave Jefferson Logan, who worked in the Senate cloakroom, was planning his nineteenth annual opossum supper in Iowa to which he invited Republican state officials and politicians. Described as "a wealthy leader of the colored population," newspapers noted that Logan generally secured "a good position each legislative session through his pull with the politicians."101"Possum Supper and Politics," Omaha (NE) Daily Bee, Dec. 2, 1903, 6, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn99021999/1903-12-02/ed-1/seq-6/; see also, "Jeff Logan and 'Possum Dinner," The Minneapolis (MN) Journal, Nov. 16, 1901, 18, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045366/1901-11-16/ed-1/seq-19/; "'Possum Supper a Great Success," The Des Moines (IA) Register, Dec. 6, 1902, 7. By 1907, the Adams County Free Press of Corning, Iowa, claimed, "What the banquets of the Gridiron club is [sic] to Washington the 'possum suppers of the Jeff Logan lodge are to Iowa's capital."102"Big Guns at 'Possum Feast," Adams County Free Press (Corning, IA), Dec. 25, 1907, 1. Founded in 1885, the Gridiron Club of Washington, DC, is a prestigious journalistic organization that holds annual dinners in which the president of the United States is generally in attendance. The dinners have gained criticism since they bring journalists close together with the political officials they cover in their news stories.

African Americans such as Jeff Logan, Alfred King, and others refused to relinquish opossum consumption to the purview of whites. In "Possum," Black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar plays upon the beliefs that African Americans possess a folk knowledge of preparing opossums, while drawing humor from the inherent lack of knowledge of whites. Dunbar uses "negro dialect"—a poetic genre103For a deeper discussion of Dunbar's poetry, see, Michael Cohen, "Paul Laurence Dunbar and the Genres of Dialect," African American Review 41, no. 2 (2007): 247–257. that appealed to literate, middle-class whites—to express his frustration and anger toward their ignorance:

Ef dey's anyt'ing dat riles me

An' jes' gits me out o' hitch,

Twell I want to tek my coat off,

So 's to r'ar an' t'ar an' pitch,

Hit 's to see some ign'ant white man

'Mittin' dat owdacious sin—

W'en he want to cook a possum

Tekin' off de possum's skin.104Paul Laurence Dunbar, Lyrics of the Hearthside (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1899), 163–164, https://archive.org/details/lyricsofhearthsi00dunb/page/162/mode/2up.

If Blacks vied to maintain a symbolic separation between Black and white opossum consumption, so, too, did whites in their repeated assertions that it was the job of people of African descent to provide, cook, and serve them opossum.

By the time Taft came to Atlanta in 1909, white opossum suppers strongly leaned on the figure of the faithful Black servant who dutifully captured and delightfully prepared the animal for white consumers.105For more information on the faithful Black servant trope, see Micki McElya, Clinging to Mammy: The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). Early twentieth-century newspapers occasionally published obituaries that figured into the faithful Black servant trope. For example, an obituary for Sam Coleman of Americus, Georgia, who was to be "buried by his white friends," highlighted his "reputation as an excellent cook," who had "for perhaps twenty years [. . .] cooked barbecue dinners and possum suppers for local epicures." "A Famous Old Cook Expires. The Long Time Cook of the Cue Club is No More," Americus (GA) Times-Recorder, July 8, 1902, 3. Writers for white newspapers were keenly aware of the racial power exuded through depictions of subservient Black labor in opossum suppers. Atlanta Constitution correspondent H.T. McIntosh reported on the "strenuous 'possum-catching campaign" in Worth County to secure a hundred of the animals for the banquet, which entailed a score of Black hunters overseen by Judge Frank Park.106H.T. McIntosh, "Worth County 'Possum Mad," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, January 9, 1909, 1, 5. Northern newspapers added to the image by relaying that "old Uncle Levi and two mammies" sent by Park to Atlanta were busy slaughtering and preparing the game. And at the banquet, Rev. Dr. J.W. Lee sang the minstrel song "Carve Him to de Heart" while two Black male waiters served opossum to the president-elect.107"Taft Feasts on Possum and the South Gets Promise of Better Things," Sun (New York, NY), Jan. 16, 1909, 1, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1909-01-16/ed-1/seq-1/; "South to Gain," Washington (DC) Herald, Jan. 16, 1909, 1. In order to provide Taft "insight of what the south was before the war," the entire event depended on Black labor.108"Banquet to Judge Taft Marks a Social Epoch in Atlanta's History," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Jan. 16, 1909, 1.

Given the popularity of southern Democratic opossum suppers, Taft knew his actions conveyed racially coded political and economic messages. "Southerners are traditionally partial to this dish," explained a Texas reporter, adding that Taft's request to attend an opossum feast "further endeared himself to the people of this section."109"Plenty of 'Possums," Bryan (TX) Morning Eagle, Jan. 2, 1909, 1. Eating or even just tasting opossum, however, was more than an act of endearment; it provided a way for Taft to become "southern" by performing in a display of white supremacy tied to an imagined antebellum culture. This invented tradition encompassed much more than Black servants catching, preparing, and serving hundreds of opossums to prominent white men at the banquet. Because the menu included numerous, heavy courses that would have required several hours to complete, it is unlikely that Taft or other diners consumed much, if any, of the opossum meat on their plates.110Daniel Frank, "Taft Ate Possum in City Auditorium," The Atlanta (GA) Journal and the Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 2, 1956, 1C. Decades later, columnist Daniel Frank explained that "onlookers noticed that Taft took one taste, and only one taste" of the barbecued opossum set before him at the 1909 banquet. "Waste was part of the point," writes food historian Helen Zoe Veit. "Perhaps nowhere more nakedly than at a banquet did wealthy Americans in the Gilded Age show off their ability to command resources for their own and their guests' pleasure, to select only the very choicest morsels from a choice dish, and to leave most of the carefully prepared, expensive food for the slop bucket or the servants."111Helen Zoe Veit, Food in the American Guilded Age (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2017), 196. Yet, in the case of the opossum, throwing away a food that had been critical to Black survival before and after slavery conveyed a socioeconomic message and a racial one.

Similar to the opossum suppers of Newnan that had begun decades earlier, the 1909 Atlanta event presented images of reunion and reconciliation. "It is beautifully emblematic of the fading away of sectionalism and the bitterness of the civil war, this spectacle of a northern Republicant-elect [sic] beaming over relays of ''possum and 'taters' in his march through Georgia," oozed a writer from Wisconsin.112"South Should Let Up," Topeka (KS) State Journal, Jan. 19, 1909, 4, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016014/1909-01-19/ed-1/seq-4/. The dish, along with its accompaniment of persimmon beer, garnered a great deal of local and national attention in the weeks and days leading up to the Atlanta event. While the opossum was closely tied to sectional identity, other items on the menu carried different messages associated with Taft's agenda and with white prejudices. "Clear-Green Turtle [soup] a la Panama" correlated to a part in Taft's speech where he emphasized the future commercial benefits that the canal offered to southern states. "Filipino Ice Cream," on the other hand, gestured toward Taft's stance on race relations, given that throughout his tour Taft had often linked Filipinos and African Americans as inferior people dependent on whites for improvement.113"Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge"; Edward Frantz, "Goin' Dixie: Republican Presidential Tours of the South, 1877–1933," (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002), 305; Needham, "William Howard Taft, The Negro, and the White South, 1908–1912," 63.

The banquet menu required careful tailoring. So did Taft's speech. To his white male Atlanta audience, Taft pledged, "I shall become the president, not of a party, but of a whole united people," reinforcing his aim to solidify white northerners and southerners.114"How New York Papers View 'Possum Banquet," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Jan. 18, 1909, 2. Some questioned Taft's motives, with South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman warning in August 1909 that "southerners should beware of Taft spreading molasses to give 'hungry office-seekers an excuse for deserting the democratic party. . . .'"115Needham, "William Howard Taft, The Negro, and the White South, 1908–1912," 96. Yet, Taft's participation in the banquet was a signal of his tolerance—and tacit support—of the Jim Crow laws enacted to maintain social control. Several months after the Atlanta event, Taft would address another white audience at a banquet in Birmingham, Alabama, claiming that he "would not have the South give up a single one of her noble traditions."116William Howard Taft, "Speech at the Chamber of Commerce Banquet, Birmingham, Ala. (November 2, 1909)," Presidential Addresses and State Papers (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1910), 402, https://archive.org/details/presidentialaddr00unit/page/402/mode/2up?view=theater&q=traditions. Taft would prove to be a consistent ally of conservative whites, giving them a free hand, enabling "a moratorium on all African American appointees throughout not only the South, but also the North" and thereby transitioning "into a new, even more lily-white era" for Republicans.117Frantz, "Goin' Dixie," 314; 317. As historian David Needham explains, "probably the most visable [sic] effort by Taft toward wooing white southerners was his appointment of independent Democrats to high federal positions" and elimination of Black governmental involvement.118Needham, "William Howard Taft, The Negro, and the White South, 1908–1912," 118.

While the opossum "topped the pinnacle of fame [. . .] basking in the sunlight of a nation's tender interest" after the Atlanta banquet, other working-class and stereotypically African American foods had the potential to further convey Taft's political stance in other states.119"Is Champagne Better to Wash Down 'Possum Than Persimmon Beer?," The Atlanta (GA) Constitution, Jan. 4 1909, 5. In looking ahead to Taft's stop in New Orleans, the Grant Parish Democrat suggested that Taft should eat alligator steak, "a great dish among the darkeys" in order "to remain on good terms with Louisiana Republicans."120"Alligator Steak," The Caucasian (Shreveport, LA), Feb. 7, 1909, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88064469/1909-02-07/ed-1/seq-8/. Subsequently, the Charlotte Observer called for Taft "to stop off in North Carolina and partake in a supper of Chatham County rabbits," which "would doubtless compare favorably with the alligator steak."121The Caucasian (Clinton, NC), Feb. 18, 1909, 1. With these foods "in his system," one newspaper editor remarked: "Mr. Taft may become practically Southern, instead of the visionary theorist that he is, particularly in connection with the negro and the Republicanizing of any of the States [. . .]."122"Alligator Steak," https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88064469/1909-02-07/ed-1/seq-8/.

Conclusion

Taft's 1909 Atlanta banquet marked the opossum's peak as a symbol of white supremacy and sectional reconciliation. After Democrats regained their political power and fully achieved Black disenfranchisement, opossum suppers diminished in popularity and, with some exceptions,123For example, the Atlanta Association of Building Owners and Managers hosted an opossum supper for Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Governor of New York, during his visit to White Sulphur Springs, Georgia, in 1930. "Roosevelt Eats and Hunts 'Possum as Georgia Guest: Partakes of Primitive Meal in Role of Adopted Son," New York Herald Tribune, Nov. 30, 1930, 11. its ties with Confederate nostalgia and Jim Crow politics faded from memory. Writing in 1916, the editor of the Jackson News in Mississippi revisited the lore surrounding the opossum, as well as the racist stereotypes:

We feel that it is a duty to shatter one of those long-cherished delusions concerning 'possums and sweet taters' as a typical Southern dish . . . . It is true that Southern homes, instinctively hospitable and willing to feed the stranger within its gates after his own heart rather than the local notion of the eternal fitness of things, serve 'possum, but generally with a silent protest that politeness alone prevents making manifest. [. . .] The dark and dismal truth is that 'possum is an all but impossible diet . . . . Possum is so largely a matter of excessive and not too fragrant fat that even Sambo, despite his reputation for never having had enough, has been known to grow tired of the same and pass it up for boiled cabbage and turnips.124Quoted in "Shattering Illusions," Gulfport (MS) Daily Herald, Nov. 29, 1916, 2.

After Reconstruction, white Democrats from Georgia had taken the lead in reinventing opossum culinary culture, once strongly associated with African American autonomy and survivance, and claimed it as their own rightful inheritance. This entailed mocking and deriding African American opossum consumption as indicative of inherently inferior racial traits. White obsessions with Black opossum consumption transformed hunting and eating the native marsupial into a nostalgic Lost Cause celebration of a supposed common culture that former enslavers claimed to share with enslaved people of African descent in the antebellum era. Since the making of a plantation imaginary filled with unforgettable opossum hunts and faithful house servants who knew the art of slaughtering, cleaning, and roasting the creature added to the dish's appeal, whites of all classes partook of opossum in part because of its association with idealized former times, remaking it, for a brief present time, into a powerful cultural symbol of Black subordination and white power.

About the Author

Stephanie N. Bryan is a PhD candidate in the history department at Emory University. She holds a Master's in Landscape Architecture from the University of Georgia, with an emphasis on historic cultural landscape management. Her dissertation examines the ways in which marginalized plant and animal species indigenous to the southeastern US—such as opossums, persimmons, muscadines, and pokeweed—survived and sometimes thrived amid destructive land use and entered into diets, cultures, economies, and politics. An earlier version of the article was “highly commended” for the 2019 Sophie Coe Prize.

Recommended Resources

Text

Bower, Anne L., ed. African American Foodways: Explorations of History & Culture. Champaign, University of Illinois Press, 2007.

Covey, Herbert C., and Dwight Eisnach. What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods and Foodways from the Slave Narratives. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press, 2009.

Giltner, Scott. Hunting and Fishing in the New South: Black Labor and White Leisure after the Civil War. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Hahn, Steven. The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Tompkins, Kyla Wazana. Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the 19th Century. New York: New York University Press, 2012.

Twitty, Michael W. The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2017.

Veit, Helen Zoe, ed. Food in the American Gilded Age. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2017.

Williams-Forson, Psyche. Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Web

Black, William R. "How Watermelons Became a Racist Trope." The Atlantic. Dec. 8, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2014/12/how-watermelons-became-a-racist-trope/383529/.

LaFrance, Adrienne. "President Taft Ate a Lot of Possums." The Atlantic. Nov. 26, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/11/president-taft-ate-a-lot-of-possums/625676/.

Winick, Stephen. "Politics and Possum Feast: Presidents Who Ate Possums." Folklife Today. Sept. 9, 2019. https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/category/animals-2/opossums/.

———. "A Possum Crisp and Brown: The Opossum and American Foodways." Folklife Today. Aug. 15, 2019. https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2019/08/a-possum-crisp-and-brown-the-opossum-and-american-foodways/.

———. "Of Possums and Presidents: Some Presidential Encounters with Opossums." Folklife Today. Aug. 12, 2019. https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2019/08/of-possums-and-presidents-some-presidential-encounters-with-opossums/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | "Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge," The New York Times, Jan. 16, 1909, 1. |

|---|---|

| 2. | David Charles Needham, "William Howard Taft, The Negro, and the White South, 1908–1912," (PhD diss., University of Georgia, 1970), 31. |

| 3. | "Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge," 1. |

| 4. | William H. Taft, "The Winning of the South," Political Issues and Outlooks: Speeches Delivered Between August, 1908, and February, 1909 (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1909), 230–234. |

| 5. | Psyche Williams-Forson examines similar paradoxes in the case of fried chicken in her chapter "More Than Just the 'Big Piece of Chicken': The Power of Race, Class and Food in American Consciousness," in Food and Culture: A Reader, 3rd ed., Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esterik, eds. (New York: Routledge, 2012): 107–118. See also Williams-Forson Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). |

| 6. | This sort of cultural appropriation persisted for over half a century after the Taft banquet, with the women of the Junior League of Charleston, South Carolina, suing Ernest Matthew Mickler, author of White Trash Cooking, in the mid-1980s for lifting what they claimed was their historical recipe for roasted opossum. For a brief discussion of cultural appropriation in this context, see Angela Jill Cooley, "Southern Food Studies: An Overview of Debates in the Field," History Compass 16, no. 10 (2018): 1–9. |

| 7. | Diane M. Spivey, "Economics, War, and the Northern Migration of the Southern Black Cook," The Peppers, Crackling, and Knots of Wool Cookbook: The Global Migration of African Cuisine (New York: State University of New York Press, 1999). |

| 8. | "Taft Eats 'Possum, Gives South Pledge," 1. |

| 9. | Don Marquis, "A Glance: Concerning the Possum and the Negro," Uncle Remus's the Home Magazine, March 1909, 26. https://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/digital/collection/printed/id/6450/rec/1. |