Overview

Reed's book surveys how he experienced different "Souths," where culture, class, ideology, and the laws emerging from segregation varied by geography in practice and form

Review

In this short book, distinguished political scientist Adolph L. Reed, Jr. offers remembrances from his early life below the Mason-Dixon line as a member of the last African American generation who came of age during Jim Crow. Reed writes with a purpose—not to chronicle his own pivotal events, hardships, or personal demons, nor to proclaim general truths. Instead, he aims to prevent misconceptions he fears are taking root about the uniform nature of the segregated South and forestall mistaken present-day lessons that ignore the role of class in the racial order of the Jim Crow South.

Reed considers himself a southerner with "a small asterisk."1Reed, Adolph L. Jr., The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives (New York: Verso Books, 2022), 9. Born in the Bronx, he was in grammar school in Washington DC, in 1954 when the Supreme Court handed down Brown v. Board of Education. Later, his parents, natives of the Arkansas Delta and New Orleans, moved back to the South where he grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas,and the Crescent City. Reed attended college in Chapel Hill, North Carolina and Atlanta and traveled the region while doing summer jobs. He taught at colleges and universities in Atlanta and worked in the city government during the second term of its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson. He then returned north where he has spent most of the last forty years—primarily at Yale, Northwestern University, and the University of Pennsylvania—teaching and writing about the importance of the working class and the role of class in racial politics.

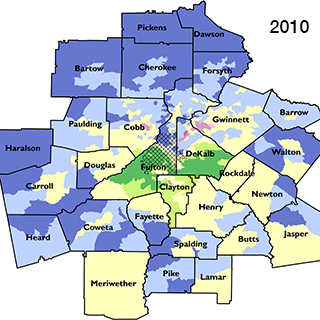

Although entitled The South, Reed's book illuminates how he and others experienced several different "Souths," where culture, class, ideology, and the laws emerging from segregation varied by geography in practice and form. Reed came to understand that Black people of all ages had to learn differing local white rules of Jim Crow if and when they moved to new places across the southern states—and even in the same city where rules applied differently store-by-store or block-by-block with varying degrees of racial humiliation. For example, one white-owned shop in New Orleans allowed Reed's family to try on clothes before purchase, but in others not shoes or not hats. Some stores permitted no Black person to try the fit of any merchandise. Mistakes in knowing a local "calculus of tolerance" could involve much more than indignity for old or young. "Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till," Reed writes, "was murdered in nearby Mississippi on a family visit from Chicago in 1955 because he unknowingly violated a local rule of subordination in a way that was interpreted as 'getting fresh' with a white woman."2Reed, 12.

"If bristling at Jim Crow's injustices were especially prominent in my consciousness," Reed writes, "it was partly because, as a result of moving around, I was always struggling to learn the local rules and grammar of subordination and how to craft a normal kid's and adolescent's life within them." As the son of well-educated Black teachers, Reed adds, "Where I lived and my family's class position also made it easier to cultivate and express indignation." 3Reed, 13.

The pervasive but varying conditions of white supremacy meant that the places where Black people could be their own free selves, away from everyday racial dangers and indignities, lay within their own segregated communities—especially in Black churches and schools where few whites often entered. As a child living in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Reed had contact with hardly any white persons because his middle-class father taught at the local historically Black college and his parents kept him close to home near the campus.

Black families deployed a variety of defenses. Traveling on a ferry boat with his grandmother, Reed asked her why chicken wire had been strung between the segregated seating areas. "Well, you see," she stage-whispered, "a lot of crazy people ride this ferry, and they have to sit on the other side."4Reed, 11–12.

Reed's vignette echoes forms of sly resistance, such as that recalled by Mississippi civil rights leader Aaron Henry, growing up under Jim Crow a generation earlier. As a boy, Henry repeatedly complained to his mother that the local white children were able to attend school for seven months but he could only go to school for five. "Aaron," his mother finally responded, "you my boy—and you don't need but five. The rest of them jokers they got to have seven." "Hell, I been cocky ever since," Henry insisted.5Worth Long, "Aaron Henry from Clarksdale," Southern Changes, 5, no. 5 (1983): 9–12. https://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc05-5_001/sc05-5_007/.

Passing as white occupies a full chapter as Reed explores the making of racial identities. During his teenage years in New Orleans, passant blanc was often accepted in the Black community as a personal choice, not so much a betrayal of the race. Reed remembers that in the city's Seventh Ward, a family of first cousins with the same surname occupied two sides of a duplex house. "The family on one side lived as black; that on the other side lived as white, and they all acknowledged one another."6Reed, 92–93. In his own family, an adult with light skin color occasionally posed as white to get some prized local delicacy or quicker service from an all-white restaurant, or to momentarily avoid a racial indignity.

Some white leaders openly acknowledged what a large number of various skin complexions meant in the real life of a society where a "one-drop rule" about race-mixing was used to demarcate the presumption of racial inferiority. Reed remembers the legendary Huey Long's brother, Earl, observing in 1960 that a single serving of red beans and rice would be enough to feed all the people in south Louisiana who were truly white (without any mixed ancestry). Alabama's two-term populist governor, James "Big Jim" Folsom, said as much in 1962, after noting the presence of a large number of light-skinned African Americans in his audience. "There's a whole lot of integratin' goin' on at night" in the state's Black Belt, he declared.7Carl Grafton and Anne Permaloff, Big Mules & Branchheads: James E. Folsom and Political Power in Alabama (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985), 68.

In concluding his chapter on "The Obsolescence of 'Passing,'" Reed remembers he came to understand at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival during the 1990s how much the vagaries of race and identity had changed with the end of Jim Crow, especially for young middle class people whose status allowed them to mingle as one at such shared events. "People who may have identified as Cubans and Hondurans, South Asians, Italian (largely Sicilian) Americans, Isleños from the Canary Islands, and other nominal whites formed a physically and behaviorally indistinguishable blur with whoever may have been (Black) Creoles."8Reed, 103.

Throughout The South, Reed investigates continuities and changes in racism and race relations that took place as he experienced the last phases of Jim Crow and the emergence of a second "New South" in Atlanta. His recollections end around 2017 as New Orleans begins removing its most prominent Confederate statues at a time when he was often in the city due to the illness and death of his mother. As if paying tribute to his mother's generation, Reed writes a full-throated analytic attack on the mythology and symbols of the Lost Cause, ripping apart their defenders' rationale for honoring enslavers who undertook a "criminal insurrection."9Reed, 123.

Reed is quick to warn that dwelling on the modern defenders of the erstwhile slave society (touting "heritage not hate") or lingering on "explicit racial hierarchies that defined Jim Crow era" should not replace a "deep examination of the discrete processes that ground and reproduce inequality in the present."10 Reed, 110. The segregationist system of white supremacy not only was more complex and opaque than popularly portrayed today but also was not "merely about white supremacy for its own sake," Reed writes. "It was the instrument of a specific order of political and economic power that was clearly racial but that most fundamentally stabilized and reinforced the dominance of powerful political and economic interests."11Reed, 137. In other words, because "the core of the Jim Crow order was a class system," Reed insists that "a simple racism/antiracism framework isn't adequate for making sense of the segregation era . . . or challenging the forms of inequality and injustice that persist."12 Reed, 140.

This part of Reed's book is not surprising for those who know his career. As a scholar and activist who spent most of his professional life teaching and writing about race and political thought in the United States, Reed has uplifted the importance of class in understanding the dynamics of racial disparities and for dismantling structures of inequality and exploitation. However, most of his remembered experiences with Jim Crow in this book do not directly support his enduring thesis. His argument about the central role of class in The South serves as a coda to his fifty years in advancing the working class as a subject of academic study and political agenda more than a conclusion revealed from the book's remembrances.

In some respects, Reed didn't need to make a case for the importance of class in the life of the South's Jim Crow. It had been done before by himself and others, some of whom he cites in his concluding chapter. One source he did not reference but surely knows is Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On March 25, 1965, at the end of the Selma-to-Montgomery march, King delivered a powerful address to the nation—one overshadowed in popular culture by his 1963 Lincoln Memorial "I Have a Dream" speech. In front of the first capitol of the Confederacy, King delivered a speech that included a popular history lesson.

Citing C. Vann Woodward's The Strange Career of Jim Crow, King told the crowd that "the segregation of the races was really a political stratagem" of the South's elite "to keep the southern masses divided and southern labor the cheapest in the land. You see," he explained, "it was a simple thing to keep the poor white masses working for near-starvation wages in the years that followed the Civil War."

King recalled the South's Populist movement when its leaders "began awakening the poor white masses and the former Negro slaves to the fact that they were being fleeced" and "began uniting the Negro and white masses into a voting bloc that threatened" to dislodge elite white control of the South's political power. "To meet this threat, the southern aristocracy began immediately to engineer this development of a segregated society" that became "the roots of racism and the denial of the right to vote," King told thousands who had marched with him for voting rights. "Through their control of mass media, they revised the doctrine of white supremacy. They saturated the thinking of the poor white masses with it." They established segregated laws often making it "a crime for Negroes and whites to come together as equals at any level. And that did it . . ."

"If it may be said of the slavery era," King proclaimed, "that the white man took the world and gave the Negro Jesus, then it may be said … that the southern aristocracy took the world and gave the poor white man Jim Crow."13"Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March," March 25, 1965, The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, Audio, 29:21, https://www.learnoutloud.com/Free-Audio-Video/History/American-History/How-Long-Not-Long/90591.

In remembering the Jim Crow he experienced, Adolph Reed has added nuance and insight to understanding the segregated South as it came to a formal end. In this book and others, Reed has placed himself in the company of southerners who came before him, scholars and activists alike, who devoted their life's work to the search for strategies and means to build a necessary interracial coalition to make democracy work in the nation—and to finally entomb Jim Crow with no chance for an afterlife.

About the Author

An adjunct with Emory University's Institute for the Liberal Arts, Steve Suitts is the author of Hugo Black of Alabama: How His Roots and Early Career Shaped the Great Champion of the Constitution (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2017). Earlier in his career, Suitts served as the executive director of the Southern Regional Council, vice president of the Southern Education Foundation, and executive producer and writer of "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," a thirteen-hour public radio series that received a Peabody Award for its history of the civil rights movement in five Deep South cities.

Recommended Resources

Text

Austin, Paula C. Coming of Age in Jim Crow DC: Navigating the Politics of Everyday Life. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Berrey, Stephen A. The Jim Crow Routine: Everyday Performances of Race, Civil Rights, and Segregation in Mississippi. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Reed, Adolph L. Jr., and Kenneth W. Warren, eds. Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2010.

Reed, Adolph L. Jr., Class Notes: Posing as Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene. New York: New Press, 2000.

———, ed. Without Justice for All: The New Liberalism and our Retreat from Racial Equality. Boudler, CO: Westview Press, 1999

Web

Class Matters. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://classmatterspodcast.org/about-the-podcast/.

Reed, Adolph L, Jr. and Merlin Chowkanyun. "Race, Class, Crisis: The Discourse of Racial Disparity and Its Analytical Discontents." Socialist Register 48 (2012): 149-175. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1970445.

Reed, Adolph L. Jr., "The Myth of Class Reductionism." The New Republic, September 25, 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/154996/myth-class-reductionism.

———. "The Trouble With Uplift." The Baffler, no. 41 (2018). https://newrepublic.com/article/154996/myth-class-reductionism.

———. "Race and Class in American Politics." Interview by Ariella Thornhill. Jacobin, March 5, 2022. YouTube video. 01:04:16. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aRvtRHmx5kY.

———. "Reckoning with Our Racial Past: A Conversation with Kwame Anthony Appiah and Adolph Reed Jr." Point/Counterpoint Series, Amherst College, November 4, 2021. YouTube video. 01:24:29. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npFdVVw2YxU.

———. "Separate and Unequal." Interview by Violet Lucca. Harper's Magazine, February 1, 2022. Audio, 46:25. https://harpers.org/2022/02/separate-and-unequal-adolph-reed-jr-the-south-jim-crow-and-its-afterlives/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Reed, Adolph L. Jr., The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives (New York: Verso Books, 2022), 9. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Reed, 12. |

| 3. | Reed, 13. |

| 4. | Reed, 11–12. |

| 5. | Worth Long, "Aaron Henry from Clarksdale," Southern Changes, 5, no. 5 (1983): 9–12. https://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc05-5_001/sc05-5_007/. |

| 6. | Reed, 92–93. |

| 7. | Carl Grafton and Anne Permaloff, Big Mules & Branchheads: James E. Folsom and Political Power in Alabama (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985), 68. |

| 8. | Reed, 103. |

| 9. | Reed, 123. |

| 10. | Reed, 110. |

| 11. | Reed, 137. |

| 12. | Reed, 140. |

| 13. | "Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March," March 25, 1965, The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University, Audio, 29:21, https://www.learnoutloud.com/Free-Audio-Video/History/American-History/How-Long-Not-Long/90591. |