Overview

In this original essay for Southern Spaces, Julian Rankin writes about the making of his book Catfish Dream: Ed Scott’s Fight for His Family Farm and Racial Justice in the Mississippi Delta (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), a portrait of a prolific farmer (the first nonwhite owner of a catfish plant in the nation's history), his family, and the racial politics of agriculture in the Deep South.

Introduction

The catfish didn't miss the current. They'd never known it. They lapped the pond all day like pace cars. At feeding time, they thrashed for their share of pellets. The farmers bred them for size and taste and texture and profit. They swam around in that little man-made lake and waited for the chopping block and the flash-frozen package. Their bodies were bullion. There were others of them, wild ones, who lived in the open waters of the river to the west. They sometimes got caught on the trotlines of grizzled river rats. Mostly they grew big as they pleased and swam deep into the crevices of the underwater earth. Fisherman told stories. "Whiskers big as bullwhips." They saw fleeting visions of this barnacled ghost ship. If you caught and ate it, they said, you'd gain all the wisdom of a century. It was part whale. Too big for the line. You could tell by the waves it made breaching the surface.

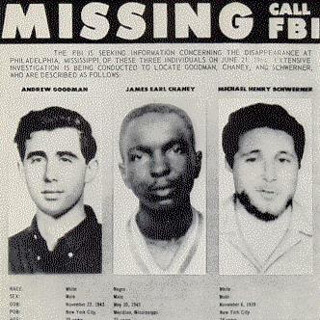

A white plantation owner in Money, Mississippi, pointed a shotgun at his father's head and threatened to blow it off, Ed Scott Jr. told me in 2013. This happened in the 1920s, when Scott was a boy. Three decades before the murder of Emmett Till put Money on all the wrong maps. The death threat was because Scott's father—who had brought his wife and children to the Delta in 1919—dreamed of being a black landowner instead of a sharecropper.

Ed Scott Jr. and I sat together in the cool-dark A/C. I sat on a stool, he reclined in an electric wheelchair. It was my first visit with him. He recounted more to me, of his tours in World War II ducking Nazi sniper fire with General Patton. How his return home to racism in Mississippi was, as James Baldwin wrote, like "a certain hope had died."1James Baldwin, "Letter from a Region in My Mind," New Yorker, November 17, 1962, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1962/11/17/letter-from-a-region-in-my-mind.

"[The people back home] didn't care about us no way," Scott said, speaking of whites' reception of black veterans. "They didn't want to see you with that uniform on back then. I was proud of that uniform, but I wasn't proud of Mississippi. Wasn't proud of Mississippi at all."

On the plight of the black soldier, Baldwin writes that he was "almost always given the hardest, ugliest, most menial work to do."2Baldwin, "Letter from a Region." After the war, Ed Scott stayed on the farm to help his father, who had then amassed hundreds of acres of Delta farmland. Scott's dream was not that the work wouldn't be ugly, or hard, or even menial. But that it would be his own work. That he would be his own master.

Scott made miracles in the cotton field, not far from Fannie Lou Hamer's visionary Freedom Farm. He carried food, prepared by his wife Edna and their children, to civil rights marchers and followed Dr. King to Selma and across the storied Edmund Pettus Bridge. He cleared a million dollars in rice in 1978. In 1983, at the height of his climb, Scott became the first ever non-white owner and operator of a catfish plant in the nation's history. It was a dream fulfilled. It was an act of necessary resistance against an industry, a government, and a society whose very identities seemed predicated on the subservience of black laborers.

"My motto is don't stop chasing your dream," Scott liked to say. "And that was my dream. To grow these catfish. Which I did."

From that first meeting with Ed Scott in 2013, I knew I wanted to write a book about his life. Over the course of the next several years, I would interview Scott, his family, his contemporaries, his lawyer. The Scott odyssey is now told in the pages of Catfish Dream: Ed Scott's Fight for His Family Farm and Racial Justice in the Mississippi Delta (University of Georgia Press, Southern Foodways Alliance Studies in Culture, People, and Place series).

Ed Scott was not alone on the journey. He modeled himself after his father, Edward Scott Sr., a sharecropper-turned-landowner who brought the family from Alabama to Mississippi in 1919. (When Scott's mother, Juanita, pleaded to Edward Senior for a return home, away from Mississippi meanness, Edward Senior replied, resolutely, "I believe I could stay in Hell one year if I knew I could move out the next.") Ed Scott took the reins of the farm and joined forces with his wife, Edna Ruth Scott, whose own father was a community organizer and prodigious farmer in nearby Mound Bayou. He partnered with his siblings and children and extended family and neighbors—including the group of black women nicknamed "the Dependables" who served as his catfish special forces. The Scotts' roots run deep. They believe in legacy and namesake.

"You never know why God let that last child be named Edward," said Rose Marie Scott-Pegues, Ed Scott's eldest daughter. "He was more like his father than any of [the other] children. [His] thing is, 'I don't want you to sell any of my land. Ever.' And I'm looking at this a million years from now. . . . This land will still be Scotts' land.

I exited the Scott home after my first visit with the Scotts, into the Delta heat as if from a sheltered cave. The orator's cadence had slowed and warped time. It had felt like days, or decades, or all time. As I drove away, these are the things I was thinking about.

1990

Worms ain't got no feets. A page in a handmade book. A caption to a hand-scrawled illustration. An earthworm with four legs and Converse. Drawn by Annette, my afternoon babysitter, a high school senior, a young black woman who chewed her gum only until the sugar ran out. This in blink-and-you'll-miss-it Shaw, Mississippi, not far from where I would later sit with Ed Scott and hear him unfurl his tale. Out of the dirt and onto the page, through the dreamy veil of imagination, the worm with feets came. My first acknowledgement of mythmaking.

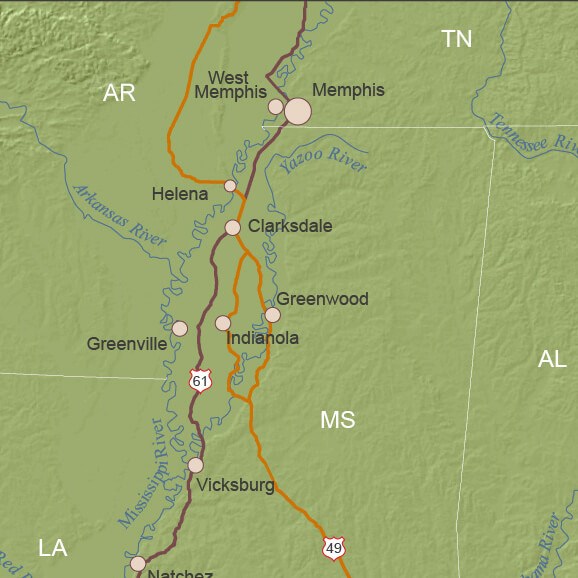

What does the Delta grow? Cotton, yes, the empire of it. The stalks like phalanxed soldiers and the bolls their thorny white heads. Propagated in postcards and genre paintings as widely as it was ginned and shipped. That is to say, all over the globe. Then rice, which Comet and Uncle Ben's came down to bid on. It, mostly white, too. Soybeans came. And corn. More than you could haul. Then catfish; out of the muddy river and into the aerated pond. But Mississippi's fertile crescent grows more than its commodities. It spawns paradox and polemic. Starkness and cacophony. Plenty and need. And of course, black and white.

My childhood home backed up to the Shaw High School practice field. For most of the hours of the day, it was quiet, until the band marched out to play. They stomped the earth and cut divots in the grass with their heels and rattled my existence. To me, their appearance was alchemy. Like rolling thunder shaped into flesh and bone. Fulfilling the latent potential of the field.

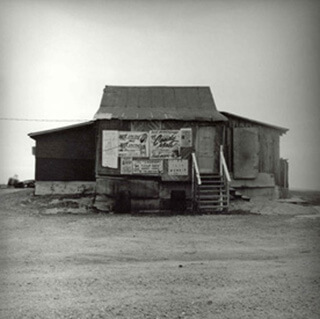

Other things the Delta grew then and still does. One-of-a-kind stores, forever "un-chained," with esoteric signs. Autocrats, plutocrats, democrats. Ramblers and gamblers. Day laborers, night laborers, nightcrawlers. Cottonmouths. Plantation houses on Indian Mounds. Jukes. Blues. Open roads. Dark and lonely cells. Government assistance. Government neglect. Lots not yet vacant but long past occupied. Ribs, bibs, bibles. Sunday dinner. Roadside eats. Potato logs on a hot tray under a heat lamp. Lessons. Teachers. Strong women—mothers and daughters, activists and administrators—who hold it all together. It spawns proximity, to the sinful roots of the nation and to graveyards and to ghosts. And also distance, an elusive recalcitrance to ever being pinned down or fully made sense of or tied neatly together. Undone shoelaces swinging on a tuba player in a marching band stampede. The notion that worms ain't got no feets coupled with the inkling that in the Delta, they probably do.

I was thinking about these things on the day after I first spoke with Ed Scott. Because in 1990, when my eyes were opening to the whole wide world, the Scotts were fighting it just a few counties away. Using a catfish as a club and barely hanging on. And I'd had no idea.

2013

Ed Scott's grandson, Daniel Scott, took me through the ruins of the catfish plant. It had opened in 1983 to fanfare with a ribbon cutting and music and a contest to see which of the workers could hand-filet fish the fastest. Commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce Jim Buck Ross looked on in his cowboy hat. He later said in a press release that "an operation with this early success is certainly a credit to our people, creating new employment at a time it is most needed."3"Mississippi Boasts First Black-owned Catfish Plant in U.S.," Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce press release, March 3, 1983.

This plant shouldn't have existed. It had been an old tractor shed, and Scott built his crowning achievement atop the bones after the local white processor refused to sell him stock so that he could process his crop like all the other farmers. When he found this out, he set up a tour of that Indianola, Mississippi plant. On the way through, the tour guide asked Scott whether he had stock in the plant or a relationship with any live haulers who would take his fish. "Nope," Scott said.

"Well, what the hell you going to do with your fish, eat 'em?!"

"Something like that," Scott told the man. "I'm down here now seeing what you're doing. I'm going to clean my own fish."

To tour the plant was to be forced to imagine what was and what might have been. Paint had faded, beams had fallen. An old television sat on the floor beneath a ceiling that was no more. Handwashing and "employees only" signs refused to budge, even while the rest of the building slowly reverted back to Delta wild. The plant closed around 1990, surviving even after the government foreclosed on the land and snatched the fish from the ponds. And in tandem with the white-dominated industry, the government constricted the flow of catfish that Scott had been buying, cash, to process and take to market himself. The plant closed at a time when national chains like McDonald's and Church's Chicken were experimenting with catfish on the menu. There was great promise for the Scotts nationally, coupled with great resistance against them locally. Under the pressure, the Scotts lasted for as long, and longer, than anyone could have imagined.

"And it was real sad because people was trying to get him out of business," said plant worker Lillie Watson-Price. "Oftentime he didn't get the finances that he need to continue to grow his own fish. . . . So what he started doing is buying the fish. Or getting it on credit. And that only lasts for so long. And they would come, and bring the fish and bring the fish and bring the fish. It was good, for a while. . . ."

"Watch your step, too," Daniel Scott told me on the way through the plant site. "That was like a storage room. That was the break room. They would change clothes, the workers."

Daniel recalled his time at the plant as a teenager. He was working the skinning line and lost a fingernail. Snatched right off. Another time, he nearly cut off his finger on the bandsaw. If I could have gone back to 1990, in the plant's final days, I would have seen the Dependables processing tens of thousands of pounds of fish a day. I would have heard them laughing, seen them grinning, felt their pride at working a dignified job, however odious and blood-soaked it may have been. The workers were almost exclusively African American, as they were at the other processing plants. There, carpal tunnel and sexual assault was rampant. But here, Scott's workers prospered. I could have peeked around a corner and seen them joshing between shifts, throwing cubes of ice, concealed in their pockets, at each other's backsides. At lunchtime, I would have walked a hundred feet across the gravel parking lot to the Scotts' home to eat, where Edna Scott had opened her own kitchen and cafeteria to feed the workers and surrounding farmers with fried fish and the bounty from her garden patch.

James Baldwin, reluctant optimist, spoke about the gap between dreams and reality. "Until the moment comes, when we, the Americans, we, the American people, are able to accept the fact . . . that on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity, that we need each other, that I am not a ward of America, I am not an object of missionary charity, I am one of the people who built the country—until this moment comes there is scarcely any hope for the American dream."4James Baldwin, Debate: Baldwin vs. Buckley, the Cambridge Union Society, Cambridge, UK, February 18, 1965, broadcast by the National Educational Television Network, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOCZOHQ7fCE.

When I was small, I heard much about problematic patriarchs. They littered my history books and struck smart poses. In civics class, we studied rhetorical structure and theoretical justice. I heard tell of trickle-down economics and bootstraps. There was an absence. All the people left out of this scheme.

Within the unfair system, there are outliers like the Scotts who make strides against the odds. Their summits are worth celebrating, even as they remind us that such climbs are precarious. They illustrate what the American dream should mean. A parcel of land, hard won, that endures across the generations. An enterprise, built through collaboration, with wealth that flows outward and downstream. A system made not solely by patriarchs but by extended families who share in the labors and define their collective futures.

"Those bees are back," said Daniel Scott, pointing to the rafters of the disintegrating processing plant. "You hear them. I thought they was gone. It's crazy, ain't it? How time will do shit?"

Ed and Edna Scott's children—especially Isaac Scott and Willena Scott-White—have restored the lost acreage, gone for thirty years to unjust foreclosure. The overgrown fields have been disked and re-planted with rice and soybeans, steadfast crops of twenty-first century Mississippi. Isaac Scott, who learned to farm from his father, now employs GPS on his combine. Willena Scott-White has plans for the Delta Farmers Museum and Cultural Learning Center in Mound Bayou to keep the stories of black farmers alive. The Scotts taught me that America's story is still being written, and all are authors of it.

Though many of the Scotts have passed on, the land remains. Near the ruins of the plant, a handful of gravestones occupy a shaded plot, in various degrees of wear. Edward Senior is buried here. He died in 1957 but looked on as his son made history. Ed Scott and Edna Scott, who passed in 2015 and 2016, are buried here too. The family cemetery is well-manicured and regularly visited. The pioneers who rest in the earth are rooted still. On Scott family land. Always, Scott family land.

About the Author

Julian Rankin is the founding director of the Center for Art & Public Exchange at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, Mississippi. He is the recipient of the Southern Foodways Alliance's first annual residency at Rivendell Writers' Colony.

Cover Image Attribution:

Ed Scott Jr. with fishing net, Leflore County, Mississippi, 2001. Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay. © Maude Schuyler Clay.Recommended Resources

Text

Cobb, James C. The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Daniel, Pete. Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

McMillen, Neil R. "Farmers without Land." In Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow, 111–155. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Reid, Debra A. and Evan P. Bennett, eds. Beyond Forty Acres and a Mule: African American Landowning Families since Reconstruction. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012.

Web

"Catfish Dream." Gravy. Podcast. June 28, 2018. https://www.southernfoodways.org/gravy/catfish-dream.

Hanson, Terrill R. "Catfish Farming in Mississippi." Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. April 2006. http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/217/catfish-farming-in-mississippi.

York, Joe. On Flavor: Delta Catfish. The Southern Foodways Alliance, 2014. https://www.southernfoodways.org/film/on-flavor/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | James Baldwin, "Letter from a Region in My Mind," New Yorker, November 17, 1962, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1962/11/17/letter-from-a-region-in-my-mind. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Baldwin, "Letter from a Region." |

| 3. | "Mississippi Boasts First Black-owned Catfish Plant in U.S.," Mississippi Department of Agriculture and Commerce press release, March 3, 1983. |

| 4. | James Baldwin, Debate: Baldwin vs. Buckley, the Cambridge Union Society, Cambridge, UK, February 18, 1965, broadcast by the National Educational Television Network, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOCZOHQ7fCE. |