Overview

Melissa Creary brings together a decade of experience as a health scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, years of extensive field work in Brazil, and her current work as a professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan to provide a comparative analysis of the role culture plays in the efficacy of public health systems in the United States and Brazil. Creary’s interdisciplinary analysis underscores differences in national beliefs about healthcare as a fundamental right and the critical impact of those beliefs when a life-threatening virus spreads rapidly across a population. Questions of health equity and justice, racial and regional disparities in healthcare, state responsibility, and partisan politics permeate her reflections on the ongoing crisis.

Commentary

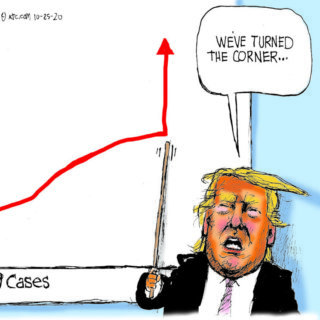

As a public health professor at the University of Michigan, I've encountered opinions about the Covid vaccine in my own family that reflect mistrust and hesitancy. I can understand this.1Melissa Creary, "Bounded Justice and the Limits of Health Equity," Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 49, vol. 2 (2021): 241–256; Creary, "Legitimate Suffering: A Case of Belonging and Sickle Cell Trait in Brazil," BioSocieties 16 (2021): 492–513; Creary, "Biocultural Citizenship and Embodying Exceptionalism: Biopolitics for Sickle Cell Disease in Brazil," Social Science & Medicine 199 (2018): 123–131; Melissa Creary, Paul Fleming, Sheeba Pawar, and Amel Omari, "Leading with HEART: Working Toward Health Equity with Anti-Racist Teaching," The Pursuit, University of Michigan School of Public Health, April 29, 2021, https://sph.umich.edu/pursuit/2021posts/leading-with-heart.html; Creary, Paul Fleming, Trivellore Eachambadi Raghunathan, "The Impact of Race on Data." University of Michigan Population Healthy Podcast, February 16, 2021, https://sph.umich.edu/podcast/season3/the-impact-of-race-on-data.html; Creary and Anne Pollock, "How COVID-19 has highlighted racism as a health risk." King's College London Podcast, June 11, 2020, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/how-covid-19-has-exposed-racism-as-a-health-risk. Like many Black households in the US, my family had little reason to "trust the science," especially that produced during the presidency of Donald Trump, who consistently endorsed racist policies and spewed racist rhetoric.2Karen Grigsby Bates, "Is Trump Really That Racist?" NPR, October 21, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/10/19/925385389/is-trump-really-that-racist. While the public health response in the United States to COVID-19 was uneven across federal, state, and local entities, the narrative about disproportionate risk and mortality became apparent early and the public health establishment eventually sprang into action to make a case for health equity in the deployment of testing, prevention, and care.3Tasleem J. Padamsee, Robert M. Bond, Graham N. Dixon, et al, "Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black and White Individuals in the US," JAMA Network Open 5, no. 1 (2022), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2788286. A survey published in January 2022, found that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy had decreased more rapidly among Blacks than among whites since December 2020. Researchers found that Blacks "more rapidly came to believe that vaccines were necessary to protect themselves and their communities."

Even with these efforts, many of my family members initially could not be persuaded to take the vaccine. I was increasingly frustrated and wished they had more faith in science. Yet, even though I was vaccinated, I shared some of their concerns, and as I've written: "how can people who have never experienced equity be trusting of a supposedly new urgent call for equity when it comes to the vaccine?"4Fabiola Cineas, "Black and Latino Communities are Being Left Behind in the Vaccine Rollout," Vox, February 24, 2021, https://www.vox.com/22291047/black-latino-vaccine-race-chicago. If there were a culture that recognized a right to healthcare, would my family feel the same way? If we expected the state to have responsibility for our health and if we had a history of the public health system systematically and consistently providing preventative treatments and care, regardless of partisan politics, would it make a difference in vaccination rates in the present crisis?

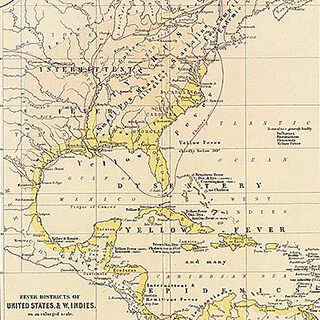

In addition to studying health justice and equity in the United States, I have researched health policy development in Brazil. Segments of the Brazilian Black Movement in the 1990s, modeled to a significant extent on the 1960s US Civil Rights Movement, demanded the right to healthcare. Black participants in my Brazilian study deployed policy-based attempts to achieve full access to citizenship—most prominently as a right to health rights.5Creary, "Bounded Justice," 241–256. My work in Brazil explored how patients, non-governmental organizations, and the Brazilian government, at state and federal levels, have contributed to the discourse of sickle cell disease (SCD) as a black disease, despite a prevailing cultural ideology of racial mixture. Drawing on ethnography and oral histories from Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Brasília, and Porto Alegre, this project charts the simultaneous constructions of race and science through SCD across Brazil. When I lived in Brazil in 2013, I was struck by just how much everyday people, within social movements and as part of civil societies, called on the Brazilian state to manage and provide healthcare access. With this in mind, I compare the public health systems in the United States and Brazil, the right to public health, and the COVID-19 vaccine.

The rollout of Covid vaccines in the United States was painfully slow. The Trump administration's Operation Warp Speed broke records in vaccine development in 2020, but floundered badly when it came to distributing immunizations in early 2021. President-elect Biden set the goal of deploying 100 million vaccinations in the first 100 days of his administration, pledging to streamline delivery throughout the nation. Shots went into arms and by mid-March 2021, a quarter of the population had received at least one vaccine; six months later that number rose to 85 percent.

Although Black Democrats were vaccinated at a lower rate than white Democrats, the values associated with vaccine hesitancy follow the lines of partisan values and ideological orientation. A Michigan study in early 2021 found the following:

. . . in the initial wave of the outbreak in May 2020, Blacks experienced more severe direct impacts: they were more likely to be diagnosed or know someone who was diagnosed, and more likely to lose their job compared to Whites. In addition, Blacks differed significantly from Whites in their assessment of COVID-19's threat to public health and the economy, the adequacy of government responses to COVID-19, and the appropriateness of behavioral changes to mitigate COVID-19's spread. Although in many cases these views of COVID-19 were also associated with political ideology, this association was significantly stronger for Whites than Blacks.

The study found that Black Michiganders had more at stake, and more to lose. They were more likely to be infected with COVID-19, so they were also more likely to adopt behaviors of compliance. A history of racist mistreatment, however, affected their compliance. Those who perceived the impact of COVID-19 as less threatening were less willing to comply with mitigating behaviors. The Michigan study demonstrates how that state is a microcosm of the United States. According to data from mid-2021, the top twenty-two states with the highest adult vaccination rates voted for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election, and some of the least vaccinated states were the most pro-Trump. This partially explains the influence that Trump had (and arguably still has) on perceptions of vaccine validity and necessity.

But major resistance remained: in September 2021, 35 percent of the eligible US population remained unvaccinated and of that group, 83 percent said they did not plan to get the lifesaving shots. By the end of 2021, 73 percent of adults eighteen and older had received at least one dose of a Covid vaccine, however, 27 percent remained unvaccinated. Of those, 42 percent reported that they "don't trust the vaccine." Vaccine hesitancy, racial inequities in distribution, and state and local disparities in healthcare funding and facilities, continued to impede vaccine delivery as first the Delta variant and then Omicron took their deadly and debilitating toll.6Staff, "A Timeline of COVID-19 Vaccine Developments in 2021," AMJC, June 3, 2021, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid-19-vaccine-developments-in-2021.

In contrast to the Covid geographies of the US, Brazilians appeared to "love vaccines," as Lucas Fontainha wrote in Undark, a digital magazine exploring the intersection of science and society. "They fight for vaccines," he continued, "they throw vaccine festivals, they kiss all the babies in the line waiting for vaccines, they camp overnight at the clinic to get a vaccine . . . even the anti-vaccination Brazilians vaccinate in secret."7Kiratiana Freelon, "Opinion: In Brazil's Successful Vaccine Campaign, a Lesson for the U.S," Undark, October 14, 2021, https://undark.org/2021/10/14/in-brazil-successful-vaccine-campaign-lesson-for-us/.

Unlike Americans in the US, Brazilians have benefitted from robust public health programs and a strong vaccine infrastructure since the 1970s. That said, throughout the pandemic, Brazilians have had to contend with Jair Bolsanaro, the "Trump of the Tropics," a man filled with authoritarian vitriol and disregard for vaccine science. Many worried that his influence would deter vaccine uptake, especially because 55 percent of the country voted for him. Bolsanaro's sphere of influence remains significant. His lukewarm stance on Covid vaccines and his refusal to pre-order them in 2020 and early 2021, resulted in many deaths. Nevertheless, a citizenry that believes healthcare is a basic right has countermanded Bolsonaro's failure of leadership. As the number of Brasilians dying from Covid increased to over 600,000 in 2021, citizens largely ignored their president, eschewed their free choice option to not vaccinate, and lined up for the shots.8Felicia Marie Knaul, Michael Touchton, Héctor Arreola-Ornelas, et al, "Punt Politics as Failure of Health System Stewardship: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic Response in Brazil and Mexico," The Lancet Regional Health: Americas 4 (2020), https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(21)00082-X/fulltext.

In 1973, Brazil created a national immunization program (Programa Nacional de Imunizações) that led to the near-eradication of polio and measles by 2000.9"National Immunization Program–Vaccination," Ministry of Health, accessed July 6, 2022, https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/programa-nacional-de-imunizacoes-vacinacao. This successful program has been strengthened by the creation of a universal healthcare and public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde or SUS) that invested (in-part) in the delivery of free public healthcare, including vaccinations to every Brazilian, codified by the Brazilian Constitution of 1988.10Jairnilson Paim, Claudia Travassos, Celia Almeida, et al, "The Brazilian Health System: History, Advances, and Challenges," Lancet 377, no. 9779 (2011): 1778–97, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21561655/. Vaccine delivery to Brazilian citizens is integrated into everyday life and normalized through informal connections, familiarity, and hyper-locality. Although Bolsanaro rejects the idea that the nation state owes a responsibility to its citizens, the state and local arms of the government (and the Constitution), disagree.11Vincent Bevins, "Despite Bolsonaro, Brazil Has Barely Any Anti-Vaxxers," Intelligencer, November 10, 2021, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2021/11/despite-bolsonaro-brazil-has-barely-any-covid-anti-vaxxers.html. Not only is the state obligated by law to distribute free services and pharmaceuticals, but citizens are mandated to be part of the process. Even those who choose private insurance must get their vaccines at SUS.

Even when an anti-science president such as Bolsonaro rails against vaccines, there is almost no way for the population to avoid receiving inoculations. In August 2021 in the city of São Paulo, the campaign Virada da Vacina reported that 99 percent of the adults in the city had been vaccinated (Bolsonaro won approximately 45 percent and 60 percent of the vote here in the run offs and general election respectively).12Isabella Menon and Paulo Eduardo Dias, "São Paulo Approaches 99% of Adults with the First Dose of the Covid Vaccine," Folha De S.Paulo, August 15, 2021, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2021/08/sao-paulo-se-aproxima-de-99-dos-adultos-com-a-primeira-dose-da-vacina-contra-a-covid.shtml; "See the Calculation Map of all Cities in Brazil," Fohla De S.Paulo, October 7, 2018, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/eleicoes/2018/veja-o-mapa-de-apuracao-de-todas-as-cidades-do-brasil/?#/cargo/presidente/local/sao-paulo/turno/1/mapa/estadual/municipio/sao-paulo/3550308. Six-hundred locations dispersed the vaccine; sixteen of these were open for walk-in or drive-up around the clock. The state provided DJs, dancing, bands, and artists on stilts to create a carnivalesque atmosphere for those waiting hours in line.

Vaccine culture in Brazil is about accessibility. Locals become part of the campaign. That means you are likely to know and have some regard for the person who comes to you in the name of immunization—in the metro stations, on street corners, or in the park. Public displays boost the vaccine's image. It is harder to retreat into spaces of disinformation when the people you know, or even don't know, seem open to receiving a vaccination. A 2021 study showed that even among vaccine-hesitant individuals in Brazil (10.5 percent of the sample), only 2.5 percent did not intend to vaccinate at all.13Daniella Campelo Batalha Cox Moore, Marcio Fernandes Nehab, Karla Gonçalves Camacho, et al. "Low COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Brazil," Vaccine 39, no. 42 (2021): 6262–6268. Still, a June 2022 report from The Lancet found that municipalities that supported Bolsonaro in the 2018 elections were those that had the worst COVID-19 mortality rates, especially during the second epidemic wave of 2021.

As of June 2022, 87.3 percent of Brazilians have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine and 79 percent have been fully vaccinated, compared with 79.8 percent of US citizens having received one dose and 67.5 percent being fully vaccinated.14COVID-19 Vaccination Tracker, Reuters, last updated July 15, 2022, https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/vaccination-rollout-and-access/. While these numbers are not vastly different, it is of note that Brazil President Bolsonaro remains in power, regularly flouting vaccine regulations and bragging about his unvaccinated status, whereas since 2021 in the United States, President Joe Biden has worked tirelessly to get vaccines in arms, bolster public health, and eliminate health disparities.15Rodrigo Pedroso, "Brazil's Bolosnaro Says He Will Not be Vaccinated Against Covid-19," CNN, October 13, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/13/americas/bolsonaro-no-vaccine-intl/index.html; Chuck Todd, Mark Murray and Carrie Dann, "Biden is True to a Key Promise: Getting More Shots in Arms," NBC News, March 19, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/meet-the-press/biden-true-key-promise-getting-more-shots-arms-n1261531; HHS Press Office, "Biden-Harris Administration Provides $121 Million in American Rescue Plan Funds to Support Local Community-Based Efforts to Increase COVID-19 Vaccinations in Underserved Communities," HHS, July 27, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/07/27/biden-harris-admin-provides-121-million-in-arp-funding-to-local-communities-for-covid-19-vaccines.html.

Early in his tenure, Biden proposed a $1.6 billion increase for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to improve core public health capacities in states and territories, modernize public health data systems, train new epidemiologists and other public health workers, and build global capacity to respond to future health threats. Some of these efforts have worked. By August 2021, Pew research reported that around three-quarters of US adults (73 percent) had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Despite these efforts, too many Americans see vaccine mandates, not as a way toward building public safety, but as extreme government overreach. Republicans and Libertarians have called repeatedly and loudly for "personal freedom" to be prioritized over public safety. Before the Supreme Court blocked the Biden administration's vaccine-or-test requirement for large private businesses in January 2022, there was an outcry for #massnoncompliance. Some scholars have called this political resistance to vaccines based on the tenets of choice and liberty, a "uniquely American predicament."16Alana Wise, "The Political Fight Over Vaccine Mandates Deepens, Despite their Effectiveness," NPR, October 17, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/10/17/1046598351/the-political-fight-over-vaccine-mandates-deepens-despite-their-effectiveness. And while the oppositional forces of conservatism and science have been noted as phenomenon elsewhere, including Brazil, the lack of a dominant US culture that trusts and respects public health and expects that the state can and should deliver it can be attributed largely to decades of right wing ideologues across many forms of media.

To date, an Omicron subvariant (BA-5) is the newest variant of concern, threatening a wave of infections and reinfections. As we continue to navigate this global pandemic, we must pay attention to the true influencers of public health. In Brazil, the public health system has a strong history of emboldening citizenry with a message of governmental duty and obligation. We'll see how this may play out in the polls come October for upcoming elections in this country. In the United States, anti-vax politicians, many of whom have themselves received the vaccine for COVID-19, have spread misinformation and anti-government rhetoric about public health. Although conservatism and evangelical religiosity has led to vaccine hesitancy, a Pew Report shows us that most Americans who go to religious services say they would trust their clergy's advice on COVID-19 vaccines. Some advocates of public health have historically prioritized local partnerships with religious leaders and institutions acknowledging this very important sphere of influence.

We must continue to undertake hard conversations about the tensions between individual freedoms and population health much as we did when H1N1 struck our collective shores. As families like my own navigate the implications of a mutating virus that generated a global pandemic, we need trusted resources that are sensitive to historical experiences and the collective common good.

About the Author

Dr. Melissa S. Creary is assistant professor in the Department of Health Management and Policy, School of Public Health at the University of Michigan and the senior director for the Office of Public Health Initiatives at the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network (ATHN). She assists ATHN in finding ways to leverage public health research and policy to make a broader impact within the bleeding and blood disorders population. Dr. Creary's areas of specialization include race and racism, genetics, identity politics, health policy, and health equity. She worked for a decade as a health scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the Division of Blood Disorders, has done extensive field work in Brazil, and has more than twenty years of bench, public health, and social science research experience.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy.

Beginning in 2022, the series expands to include 1000-word blog posts, as well as longer commentaries, essays, articles and media productions that address the public health and political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic from multiple viewpoints. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Cover Image Attribution:

Portraits of Resilience: Brazil, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil, July 21, 2020. Photograph by Raphael Alves. Courtesy of Flickr user International Monetary Fund. Creative Common license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.Recommended Resources

Text

Fonseca, Elize Massard da, Nicoli Nattrass, Lira Luz Benites Lazaro, and Francisco Inácio Bastos. "Political Discourse, Denialism and Leadership Failure in Brazil's Response to COVID-19." Global Public Health 16, no. 8–9 (2021): 1251–1266.

Gramacho, Wladimir G., and Mathieu Turgeon. "When Politics Collides with Public Health: COVID-19 Vaccine Country of Origin and Vaccination Acceptance in Brazil." Vaccine 39, no. 19 (2021): 2608–2612.

Mobarak, Ahmed Mushfiq, Andrew Sunil Rajkumar, and Maureen Cropper. "The Political Economy of Health Services Provision in Brazil." Economic Development and Cultural Change 59, no. 4 (2011): 723–751.

Moore, Daniella Campelo Batalha Cox, Marcio Fernandes Nehab, Karla Gonçalves Camacho, et al. "Low COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Brazil." Vaccine 39, no. 42 (2021): 6262–6268.

Ochieng, Candy, Sabrita Anand, George Mutwiri, . "Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Visible Minority Groups from a Global Context: A Scoping Review." Vaccines 9, no. 12 (2021): 1445.

Otovo, Okezi T. Progressive Mothers, Better Babies: Race, Public Health, and the State in Brazil, 1859–1945. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016).

Web

1st Brazilian National Digital Health Strategy 2020–2028 Monitoring and Evaluation Report. (Ministry of Health of Brazil: 2021). https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/1st_brazilian_national_digital_health_strategy.pdf.

Beeland, DeLene. "Mapping the Spread of COVID-19 in Brazil." University of Florida Emerging Pathogens Institute. April 30, 2021. https://epi.ufl.edu/articles/mapping-covid19-spread-in-brazil.html.

Bevins, Vincent. "Despite Bolsonaro, Brazil has Barely Any Anti-Vaxxers." Intelligencer. November 10, 2021. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2021/11/despite-bolsonaro-brazil-has-barely-any-covid-anti-vaxxers.html.

Bigoni, Allesandro, Ana Maria Malik, Renato Tasca, et al. "Brazil's Health System Functionality Amidst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Resilience." The Lancet Regional Health: Americas 10 (2022). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00039-4/fulltext.

Macinko, James and Célia Szwarcwald, eds. A Panorama of Health Inequities in Brazil. International Journal of Equity in Health 15 (2016). https://www.biomedcentral.com/collections/HIB.

Otto, Frank. "3 Lessons The U.S. Could Learn from Brazil's Universal Health Care System." Drexel News Blog. November 29, 2017. https://newsblog.drexel.edu/2017/11/29/3-lessons-the-u-s-could-learn-from-brazils-universal-health-care-system/.

"Vaccines and Public Health in Brazil: Politics vs. Science." Brazil LAB at Princeton University. February 25, 2021. YouTube video, 01:18:50. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwUSCwAXxu0&t=422s.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Melissa Creary, "Bounded Justice and the Limits of Health Equity," Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 49, vol. 2 (2021): 241–256; Creary, "Legitimate Suffering: A Case of Belonging and Sickle Cell Trait in Brazil," BioSocieties 16 (2021): 492–513; Creary, "Biocultural Citizenship and Embodying Exceptionalism: Biopolitics for Sickle Cell Disease in Brazil," Social Science & Medicine 199 (2018): 123–131; Melissa Creary, Paul Fleming, Sheeba Pawar, and Amel Omari, "Leading with HEART: Working Toward Health Equity with Anti-Racist Teaching," The Pursuit, University of Michigan School of Public Health, April 29, 2021, https://sph.umich.edu/pursuit/2021posts/leading-with-heart.html; Creary, Paul Fleming, Trivellore Eachambadi Raghunathan, "The Impact of Race on Data." University of Michigan Population Healthy Podcast, February 16, 2021, https://sph.umich.edu/podcast/season3/the-impact-of-race-on-data.html; Creary and Anne Pollock, "How COVID-19 has highlighted racism as a health risk." King's College London Podcast, June 11, 2020, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/how-covid-19-has-exposed-racism-as-a-health-risk. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Karen Grigsby Bates, "Is Trump Really That Racist?" NPR, October 21, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/10/19/925385389/is-trump-really-that-racist. |

| 3. | Tasleem J. Padamsee, Robert M. Bond, Graham N. Dixon, et al, "Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black and White Individuals in the US," JAMA Network Open 5, no. 1 (2022), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2788286. A survey published in January 2022, found that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy had decreased more rapidly among Blacks than among whites since December 2020. Researchers found that Blacks "more rapidly came to believe that vaccines were necessary to protect themselves and their communities." |

| 4. | Fabiola Cineas, "Black and Latino Communities are Being Left Behind in the Vaccine Rollout," Vox, February 24, 2021, https://www.vox.com/22291047/black-latino-vaccine-race-chicago. |

| 5. | Creary, "Bounded Justice," 241–256. My work in Brazil explored how patients, non-governmental organizations, and the Brazilian government, at state and federal levels, have contributed to the discourse of sickle cell disease (SCD) as a black disease, despite a prevailing cultural ideology of racial mixture. Drawing on ethnography and oral histories from Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Brasília, and Porto Alegre, this project charts the simultaneous constructions of race and science through SCD across Brazil. |

| 6. | Staff, "A Timeline of COVID-19 Vaccine Developments in 2021," AMJC, June 3, 2021, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid-19-vaccine-developments-in-2021. |

| 7. | Kiratiana Freelon, "Opinion: In Brazil's Successful Vaccine Campaign, a Lesson for the U.S," Undark, October 14, 2021, https://undark.org/2021/10/14/in-brazil-successful-vaccine-campaign-lesson-for-us/. |

| 8. | Felicia Marie Knaul, Michael Touchton, Héctor Arreola-Ornelas, et al, "Punt Politics as Failure of Health System Stewardship: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic Response in Brazil and Mexico," The Lancet Regional Health: Americas 4 (2020), https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(21)00082-X/fulltext. |

| 9. | "National Immunization Program–Vaccination," Ministry of Health, accessed July 6, 2022, https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/programa-nacional-de-imunizacoes-vacinacao. |

| 10. | Jairnilson Paim, Claudia Travassos, Celia Almeida, et al, "The Brazilian Health System: History, Advances, and Challenges," Lancet 377, no. 9779 (2011): 1778–97, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21561655/. |

| 11. | Vincent Bevins, "Despite Bolsonaro, Brazil Has Barely Any Anti-Vaxxers," Intelligencer, November 10, 2021, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2021/11/despite-bolsonaro-brazil-has-barely-any-covid-anti-vaxxers.html. |

| 12. | Isabella Menon and Paulo Eduardo Dias, "São Paulo Approaches 99% of Adults with the First Dose of the Covid Vaccine," Folha De S.Paulo, August 15, 2021, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2021/08/sao-paulo-se-aproxima-de-99-dos-adultos-com-a-primeira-dose-da-vacina-contra-a-covid.shtml; "See the Calculation Map of all Cities in Brazil," Fohla De S.Paulo, October 7, 2018, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/eleicoes/2018/veja-o-mapa-de-apuracao-de-todas-as-cidades-do-brasil/?#/cargo/presidente/local/sao-paulo/turno/1/mapa/estadual/municipio/sao-paulo/3550308. |

| 13. | Daniella Campelo Batalha Cox Moore, Marcio Fernandes Nehab, Karla Gonçalves Camacho, et al. "Low COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Brazil," Vaccine 39, no. 42 (2021): 6262–6268. |

| 14. | COVID-19 Vaccination Tracker, Reuters, last updated July 15, 2022, https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/vaccination-rollout-and-access/. |

| 15. | Rodrigo Pedroso, "Brazil's Bolosnaro Says He Will Not be Vaccinated Against Covid-19," CNN, October 13, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/13/americas/bolsonaro-no-vaccine-intl/index.html; Chuck Todd, Mark Murray and Carrie Dann, "Biden is True to a Key Promise: Getting More Shots in Arms," NBC News, March 19, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/meet-the-press/biden-true-key-promise-getting-more-shots-arms-n1261531; HHS Press Office, "Biden-Harris Administration Provides $121 Million in American Rescue Plan Funds to Support Local Community-Based Efforts to Increase COVID-19 Vaccinations in Underserved Communities," HHS, July 27, 2021, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/07/27/biden-harris-admin-provides-121-million-in-arp-funding-to-local-communities-for-covid-19-vaccines.html. |

| 16. | Alana Wise, "The Political Fight Over Vaccine Mandates Deepens, Despite their Effectiveness," NPR, October 17, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/10/17/1046598351/the-political-fight-over-vaccine-mandates-deepens-despite-their-effectiveness. |