Overview

Elliott J. Gorn highlights the often forgotten work and legacy of Mother Jones, prominent union organizer and activist, whose figure presided over a large rally for striking Alabama coal miners on August 4, 2021, in Brookwood, Alabama.

Blog post

Mother Jones died ninety years ago, but she was back in Alabama this July. It was not her first visit to the state. She came to Birmingham and Bessemer to support striking railroad workers in 1894, and a few years later, she took a job in a Tuscaloosa cotton mill to report on the wretched working conditions faced by women and children.

Truth be told, it was not the real Mother Jones but a twelve-foot inflatable likeness of her that showed up at the Brookwood Ballpark for a rally in support of striking coal miners. Roughly two thousand people came out to the event, and many stopped to have their picture taken with "the grand old lady of the labor movement." Present were representatives of labor unions from across the country—longshoremen, flight attendants, municipal employees, as well as members of the United Mine Workers of America from West Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

The inflatable likeness belongs to the Mother Jones Heritage Project, a pro-labor organization based in the Chicago area. Jim Dixon of Springfield, Illinois, drove her down to Alabama. Now retired, he was president of Springfield Trades and Labor Council, a member of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSME), and a union activist. He came to Alabama not only with Mother Jones, but with checks for the miners' strike fund from his AFSCME local, and from the Mother Jones Foundation.

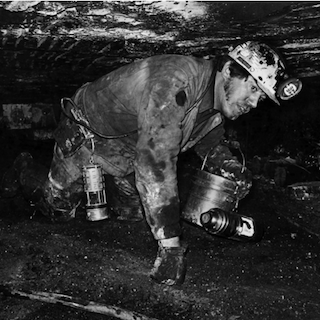

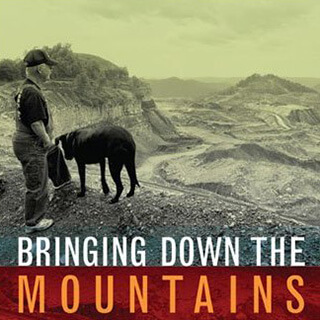

The immediate spur for Dixon's trip to Alabama was the five-month-old strike, called by the United Mine Workers of America, of over a thousand workers in Tuscaloosa County. They took a big pay cut four years ago when their employer, the Walter Energy Company, went bankrupt. The new owner, Warrior Met, refuses to negotiate restoration of pay, overtime, and holidays now that the old contract has expired, despite the fact that coal shipments to China, Europe, and Latin America have made the company profitable once again.

We think of Alabama as a deep red "right-to-work" state, yet it has a long history of union organizing. In Bessemer, just half an hour east on Interstate 20, was the big organizing drive against Amazon a few months ago. The contradictions of red state unionism are right on the surface. Many of the striking miners are Trump Republicans who loved his promise to "bring back coal." But they recognize too that there has been no support for the strike coming from the right, no GOP politicians standing in solidarity for fair wages, no Fox News coverage. Meanwhile, the law has winked at a few incidents of violence against the strikers. But there is also a contradiction from the left. Coal is a filthy fuel, a major contributor to global warming, yet promises of "good paying green jobs" sound like pie in the sky to working class families who have struggled across generations for the bit of security offered by UMWA jobs.

Jim Dixon said he was struck by several things during his time in Alabama. He was impressed with the size of the crowd and the energy at the rally staged by the United Mine Workers. He also mentioned that it was a well-integrated event—about a fifth of the striking miners are African American, and he felt a strong spirit of solidarity across racial lines. The miners Dixon spoke with were upbeat, ready to keep fighting for a contract. Still, he added, this strike isn't getting the press attention it deserves. Not just newspapers, but unions too need to go back to educating Americans about economics. The biggest owner of Warrior Met, he noted, was BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager. "Workers know they're getting kicked," Dixon said, "but they don't always know whose foot is in the boot."

"An injury to one is an injury to all," he added, quoting the slogan of the nineteenth-century Knights of Labor. Dixon's grandfather, a coal miner, narrowly escaped death in Illinois's horrific Cherry Mine Disaster in 1909. Organized labor, Dixon emphasized, was a family; working people needed security, safety, and decent pay to keep their children properly fed and clothed. Mother Jones, he pointed out, always referred to "the family of labor" because unions looked out for households and communities, not just individuals.

That is why Mother Jones remains an important symbol for the labor movement. Mary Harris Jones always called out whose foot was in the boot. Born in 1837, a famine immigrant from Ireland in 1850, she lost her husband and four children to a yellow fever epidemic in Memphis when she was thirty years old, then had her seamstress shop burned out in the Chicago fire of 1871. Tragedy only heightened her empathy for her fellow workers and fearlessness toward the powerful. She studied the social conditions of Gilded Age America, developed her oratorical skills, and as an elderly woman she emerged as Mother Jones, the fierce leader of a thousand labor battles.

Mother Jones organized men and women, Black and white, immigrant and native-born workers. Across industries, from steel milling to needle trades, but especially coal mining, she gave exploited American workers hope of gaining some control over their lives and bettering their conditions. To dramatize the exploitation of child labor in America, she even organized one hundred striking kids into "the March of the Mill Children," from Philadelphia to President Theodore Roosevelt's summer home on Long Island.

By the early twentieth century, Mother Jones was one of the most famous women in America. Local officials locked her up to keep her away from strike zones, but she always said she could raise more hell in prison than out. "The most dangerous woman in America," one prosecutor called her; "She is a wonder," her friend Carl Sandberg wrote; "The walking wrath of God," Upton Sinclair declared. Meridel Le Sueur, just fourteen years old when she first heard Mother Jones speak, recalled, "I felt engendered by the true mother, not the private mother of one family, but the emboldened and blazing defender of all her sons and daughters."

In Chicago, the Mother Jones Heritage Project is negotiating with the city to erect a statue of her downtown. As America reevaluates who its heroes are, rethinks who deserves to be immortalized in bronze, here is a forgotten figure, larger than life, an immigrant, a woman, an elderly person, a worker, inspiring others to "pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living." Just ask the miners—Mother Jones lives!

About the Author

Elliott J. Gorn teaches history at Loyola University Chicago. He is the author of Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), and most recently, Let the People See: The Story of Emmett Till (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Cover Image Attribution:

Mother Jones, ca. 1910–1915. Photograph by Bains News Service. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/pictures/item/2014695950/.Recommended Resources

Text

Adams, Charles Edward. Blockton: The History of an Alabama Coal Mining Town. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012.

Gorn, Elliott J. "Mother Jones: Ireland to North America to Ireland." American Journal of Irish Studies 11 (2014): 11–30.

———. Mother Jones: the Most Dangerous Woman in America. New York: Hill and Wang, 2002.

Steel, Edward M., ed. The Speeches and Writings of Mother Jones. Pittsburg, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1988. https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735035254105/viewer#page/1/mode/2up.

———. The Correspondence of Mother Jones. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985. https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735057897435/viewer#page/1/mode/2up.

Waggoner, Eric G. "Radical Rhetoric, American Iconography, and 'The Autobiography of Mother Jones.'" Appalachian Journal 32, no. 2 (2005): 192–210.

Web

Day, James Sanders. "Mining Towns in Alabama." Encyclopedia of Alabama. Last updated November 2, 2018. http://eoa.auburn.edu/article/h-3692.

Gorn, Elliott J. "The History of Mother Jones." Mother Jones. May/June 2001. https://www.motherjones.com/about/history/.

Kelly, Kim. "The Coal Miners' Wives Keeping a Strike Alive in Alabama." Elle. August 12, 2021. https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/a36732756/warrior-met-mining-strike-alabama/.

Mother Jones Museum. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.motherjonesmuseum.org/.