Overview

Aaron Witcher reviews Valérie Loichot's Water Graves: The Art of the Unritual in the Greater Caribbean (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2020).

Review

Water Graves investigates how contemporary writers and artists of the greater Caribbean (such as Jason deCaires Taylor) reinvest sites of racialized violence and environmental degradation—as so many manifestations of "unritual"—with a new sense of the sacred that allows for remembrance and re-humanization. Rituals—be they initiations, funerary rites, or collective acts of remembrance—confer "humanity" on those who practice them and sacredness on the places of these practices. The unritual comprises moments and spaces of desecration. Unritual occurs when rituals are ignored, violently suppressed or obstructed outright, and where so-called "natural" spaces are commodified, exploited, and profaned. Closely appended to Loichot's unritual are the notions of "undead" and "unrest"; the liminal zone of (non)being they demarcate emphasizes the unritual's alienating, unsettling, and dehumanizing effects before and beyond the grave.

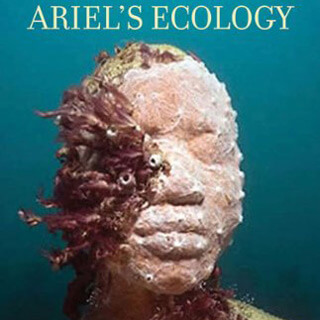

Off the coast of Grenada, several meters below the Caribbean surface, stands Jason deCaires Taylor's Vicissitudes. It is an installation of statues which, at first glimpse, shows a group of men and women arranged in a large circle, holding hands as they gaze outward along the ocean floor. The figures bear bright red, pink, and violet protrusions of coral, undulating gossamers of seaweed, and the occasional sea star. The texture and topography of these statues' skin—their pores, wrinkles, and scars—provide the ideal environment for aquatic life to take root and repopulate this portion of ocean floor. Vicissitudes also offers another, more haunting kind of repopulation, this time by the specters of the Triangular Trade: the innumerable captives thrown overboard after dying in transit during the Atlantic crossing and condemned to perish, away from ancestral lands and families that could offer funerary rites or remembrance. As the installation confronts the degradation of coral environments, its underwater surroundings also beckon and materialize the (un)dead of the African Diaspora whose memory—likewise rarefied and threatened—inhabits these statues alongside the coral. Vicissitudes, a monument that explores the creative and memorial agency of Caribbean underwater spaces, serves as one of many objects that Valérie Loichot examines in her book, Water Graves: The Art of the Unritual in the Greater Caribbean.

An interdisciplinary exegesis in the fields of Postcolonial Studies, Caribbean Studies, African Diaspora Studies and Ecocriticism, Water Graves investigates objects across many mediums that, like Vicissitudes, work through or heal the effects of unritual. The oeuvre of poet-philosopher Edouard Glissant serves as the opening and the theoretical springboard for the rest of the book. Here, Loichot engages the notion of "relational sacred," which draws heavily from Glissant's concepts of creolization, relaying, and entour or "surroundings."1As Loichot explains, "Entour signifies for Glissant the whole environment comprising the poem, human and nonhuman animals, vegetation, rocks, lavas, and 'nature' and 'culture.' The latter terms lose meaning since they exist in a continuum, not in a system of opposition" (28). For another in-depth look at Glissant's entour, see Carrie Noland, "Éduoard Glissant: A Poetics of the Entour," in Poetry After Cultural Studies, ed. Heidi R. Bean and Mike Chasar (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011), 143–172. This "relational sacred"—which extends the expressions of memory or ritual beyond religious confines—informs more specifically how the objects featured in Water Graves's chapters (objects of literature, music, film, visual arts, poetry, and photography) repair the effects of unritual.

Loichot's "Graves for Katrina" examines the work of mourning effected by visual artists in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Featuring the photography of Eric Waters and the paintings and mixed-media exhibitions of Radcliffe Bailey and Epaul Julien, this chapter considers the (mis)use and subversion of frames as devices that circumscribe the spatial, temporal, and conceptual boundaries of a work. For instance, Bailey's installation, Windward Coast–West Coast Slave Trade (2009–18)—which is comprised of a large sea-like arrangement of salvaged piano keys from which emerges a lone, "African" head—eschews "framing" within a singular meaning or temporality. By evoking at once the "victims of the Middle Passage, Katrina, or [prophetically] the Haitian Earthquake" Bailey's installation goes beyond the temporal frames that would separate these events (101, 66). These overlapping and recursive temporalities, argues Loichot, prompt spectators to see similar logics of "unritual" at work in all of them, logics that signal the longue-durée effects of racialized slavery whereby Black people remain subject to violence and dehumanization.

As the objects of Bailey, Waters, and Julien spill out of conventional "frames" or conceptual boundaries, Loichot's analysis flows into the murky waters of Katrina and its racial and environmental violence in "Mami Wata the Formidable." Loichot wades through the ethical ambiguity of Kara Walker's exhibit/book, After the Deluge, and Beyoncé's visual album, Lemonade, which represent—and potentially reproduce—the violence of slavery and Katrina. Yet, in this representation and acknowledgement, Walker and Beyoncé—like Mami Wata, the titular voudou figure who grants life and death to those lost at sea—also sanctify the victims of the violence their objects traverse. Through Julia Kristeva's notion of "muck," Loichot shows the creative and "sacred" potential of Walker's and Beyoncé's portrayals of violence as the "abject substance [that] paradoxically—and horrifyingly—becomes the amniotic fluid of a new birth" (112).

"Drowned," delves further into fluid spaces—this time of the ocean floor—via Jason deCaires Taylor's Cancún Underwater Museum and Édouard Duval Carrié's paintings. These works, Loichot contends, project spectators into the space of the drowned while teasing out the links between environmental degradation, those thrown overboard during the Middle Passage, and the migrants who drown while crossing the Mediterranean today. From these underwater spaces of death, "Stone Pillow and Bone Water" turns to the "hard materiality of words" which are likened to the raw material that M. NourbeSe Philip and Natasha Trethewey shape into poetic "graves, stones, or monuments to the neglected, forgotten, or desecrated dead" (177). Loichot details how Philip deconstructs and reshapes the juridical/scientific language implicated in justifying racialized slavery: "As herself both a lawyer and a poet, Philip must rectify the law . . . by giving humanity and sacred back to the victims of the legalized unritual, through her poetic creation. Poetry—poiesis as act of making—relays a faulty even criminal, law" (204).

As the variety of objects featured in Water Graves indicates, Loichot's relational methodology echoes and enacts principles of Édouard Glissant's notion of "Relation," particularly that of "relaying" understood as: "an act of solidarity between those touched by the unritual, such as humans and their hurt ecologies. [Relaying] calls for disciplines like literary and artistic interpretation, history and science, to join forces where they meet the epistemological abyss of the unknown" (19). By bringing the notion of entour—which implicates so-called "natural" surroundings in "human" creativity and activity—to bear on its analyses, Water Graves effectively broadens the scope of the unritual to include the natural world, underlining connections between racial violence and environmental destruction. One of the strengths of this relational methodology resides in its juxtaposition of disparate objects. These juxtapositions not only highlight the connections among seemingly distinct historical phenomenon; they also bring into conversation creative works that confront the systems responsible for propagating the unritual. The hybrid figures in Beyoncé's Lemonade (lasiwène or the siren) and Jason deCaires Taylor's Vicissitudes, for example, challenge ontological boundaries that condition spaces of racialized violence and environmental degradation—boundaries between life and death, human and coral, sacred and profane, memory and oblivion. Loichot's treatment of these two objects—which come from different entours and mediums—reveals the poetical, creolizing, and memorial potential of underwater spaces in the Greater Caribbean. As Loichot puts it, "[t]he water is thus not a dividing line but a site of passage, flux, communication and confusion between . . . realms" (154).

Though my appraisal of Water Graves remains predominantly laudatory, I will signal two critiques in terms of its methods and conceptual vocabulary. Loichot's powerful juxtapositions showcase the poetic possibilities of creating a network of oeuvres motivated by the desire to heal and move beyond the unritual. But Water Graves's relational approach sometimes sidesteps the paradoxes highlighted by this kind of comparative work. As Shu-mei Shih proposes in her essay "Comparison as Relation," relating ostensibly dissimilar objects allows one to deconstruct boundaries (disciplinary or otherwise) erected by "certain interests" or "the workings of Power" (which Water Graves certainly does).2Shu-mei Shih, "Comparison as Relation," Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses, ed. Rita Felski and Susan Friedman (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2013), 79. Yet, it is equally important, Shih notes, to "evacuate and analyze" how these economic, national, or other interests nevertheless infuse the objects of comparison and their relations.3Shih, 84. That Beyoncé's album (and related concerts) garnered hundreds of millions of dollars within neoliberal capitalism—a socioeconomic system predicated on exploiting women, people of color, and vulnerable workforces in developing countries—constitutes an aporia that Water Graves acknowledges without exploring.4As indicated by the Pew Research Center, wage gaps continue to track along gender and racial lines in the U.S. Eileen Patten, "Racial, gender wage gap persists in U.S. despite some progress," Pew Research Center, July 1, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/01/racial-gender-wage-gaps-persist-in-u-s-despite-some-progress/. Though Water Graves recognizes the album's imbrication with capitalist profit—casting Beyoncé as an embodiment of the capitalistic deity Mami Wata—it doesn't investigate how the economic "interests" underwriting her album inflect and/or constrain the work of healing or moving beyond the unritual.5bell hooks, "Beyoncé's Lemonade is capitalist money-making at its best," in The Guardian, May 11, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/may/11/capitalism-of-beyonce-lemonade-album. As bell hooks points out, both Beyoncé and Serena Williams are featured in the album wearing sports clothing, as Beyoncé's sports clothing line—Ivy Park—would appear the same year as Lemonade, thereby walking a fine line between dissident discourse and advertisement. This is not to say that Beyoncé's discourse is invalidated by this antagonism, nor that one can totally disengage from the "workings of Power," particularly in the era of globalization; rather, I mean to emphasize the importance of situating the discourse of a given object within its material conditions and outcomes, especially as these conditions and outcomes often constitute sites of unritual, which complicate our readings of these objects and the ways in which they relate to each other.

My second critique relates to the use of terms historically operationalized in colonial contexts to exclude non-European populations. Although its creolizing methodology works across disciplinary and cultural frameworks, Water Graves employs certain universalizing notions, notably "humanity," whose investment in a colonial epistemological tradition is not always fully interrogated. As the philosopher and novelist Sylvia Wynter writes in "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/ Power/Truth/ Freedom," the term "humanity" has historically been invoked to exclude racialized persons from its prerogatives, and has, in fact, depended on the racialized "Other," relegated to a space of unritual in order to mark its boundaries. Indeed, Wynter tracks how the conceptions of "human" and "humanity" came to correspond with "reason" and "rationality" in Renaissance Europe (and continue to do so today), whereas the conditions of "subrationality" and uncivilization were used to characterize colonized populations.6Sylvia Wynter, "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument" in CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003): 266, 301. In other words, under the guise of describing the entire "human race," the term "humanity" has come to reify and universalize Western values and ideals. Although Water Graves's introduction construes "humanity" in an inclusive way—proposing that rituals "of the sacred" writ large are "a defining mark of humanity"—the text leaves unattended its watermark of exclusion and eurocentrism (7). The uninterrogated use of "humanity," then, potentially constitutes a discursive site of "unritual"—what Loichot's objects and analysis strive to "heal"—as its eurocentric and exclusionary connotations of so-called "rationality" and "civilization" implicitly accompany its evocation. Explicitly deconstructing the history and usage of "humanity" while signaling a plurality of humanities would not only eliminate the tension created by the colonial baggage of this term, but would also dovetail with Glissant's conception of Relation which rejects universalizing concepts, while insisting on multitudinous humanities.

Water Graves is an important and compelling study for anyone interested in the Caribbean, Afro-Diasporic experiences, colonialism, and slavery, as it engages with the enduring aftereffects of their histories, including how artists reinscribe them with new meanings. Loichot's work merits praise for its epistemological and methodological originality as she extends Glissant's concepts of Relation and relaying. In literary, artistic, and musical objects from across the Caribbean, Loichot skillfully interweaves questions of (post)colonial legacies, environmental degradation, and social justice in order to explore these objects' often unexpected correspondences as well as their tensions. Ultimately, Loichot demonstrates how literary and artistic exegesis "relate" with its artistic objects in ways that not only explore the memory and trauma of the unritual and its resacralization, but that also engage new modalities and transdisciplinary vocabularies for comparing creative works across the broader Caribbean.

About the Author

Aaron Witcher is a PhD Candidate in French and Francophone Studies at The Pennsylvania State University.

Cover Image Attribution:

The Silent Evolution by Jason deCaires Taylor at M.U.S.A. (Museo Subacuático de Arte) in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico near the island of Isla Mujeres and the coast of Punta Nizuc, Cancún, Mexico, February 10, 2017. Photograph by Flickr user Mark Harris.Recommended Resources

Text

Green, Tara T. Reimagining the Middle Passage: Black Resistance in Literature, Television, and Song. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2018.

Loichot, Valerie. “Édouard Glissant’s Graves.” Callaloo 36, no. 4 (2013): 1014–1032.

Mustakeem, Sowande M. Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2016.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Sharpe, Jenny. Immaterial Archives: An African Diaspora Poetics of Loss. Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2020.

Shih, Shu-mei. “Comparison as Relation.” In Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses, edited by Rita Felski and Susan Friedman, 79–98. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Smallwood, Stephanie E. Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Taylor, Jason deCaires, McCormick, Carlo, and Helen Scales. The Underwater Museum: The Submerged Sculptures of Jason deCaires Taylor. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2014.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003): 257–337.

Web

hooks, bell. “Beyoncé’s Lemonade is capitalist money-making at its best.” The Guardian. May 11, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/may/11/capitalism-of-beyonce-lemonade-album.

Taylor, Jason deCaires. “Selected Works.” Accessed August 8, 2020. https://www.underwatersculpture.com/works/recent/.

Julien, Epaul. “New Orleans Photography.” Epaul Julien Studio. Accessed August 6, 2020. https://www.epauljulien.com/portfolio_page/1803/.

“Kara Walker at the Met: After the Deluge.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 9, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2006/kara-walker.

Slave Voyages. Emory University Center for Digital Scholarship. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://www.slavevoyages.org.

Similar Publications

| 1. | As Loichot explains, "Entour signifies for Glissant the whole environment comprising the poem, human and nonhuman animals, vegetation, rocks, lavas, and 'nature' and 'culture.' The latter terms lose meaning since they exist in a continuum, not in a system of opposition" (28). For another in-depth look at Glissant's entour, see Carrie Noland, "Éduoard Glissant: A Poetics of the Entour," in Poetry After Cultural Studies, ed. Heidi R. Bean and Mike Chasar (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011), 143–172. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Shu-mei Shih, "Comparison as Relation," Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses, ed. Rita Felski and Susan Friedman (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2013), 79. |

| 3. | Shih, 84. |

| 4. | As indicated by the Pew Research Center, wage gaps continue to track along gender and racial lines in the U.S. Eileen Patten, "Racial, gender wage gap persists in U.S. despite some progress," Pew Research Center, July 1, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/01/racial-gender-wage-gaps-persist-in-u-s-despite-some-progress/. |

| 5. | bell hooks, "Beyoncé's Lemonade is capitalist money-making at its best," in The Guardian, May 11, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/may/11/capitalism-of-beyonce-lemonade-album. As bell hooks points out, both Beyoncé and Serena Williams are featured in the album wearing sports clothing, as Beyoncé's sports clothing line—Ivy Park—would appear the same year as Lemonade, thereby walking a fine line between dissident discourse and advertisement. |

| 6. | Sylvia Wynter, "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument" in CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003): 266, 301. |