Overview

Karlsberg and Bransford introduce 360-degree video recordings from inside Sacred Harp's "hollow square," around which singers sit, organized by voice part and facing each other, as a procession of leaders take turns directing songs. The hollow square is the spatial, aesthetic, and spiritual center of this international music culture with roots in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, and Texas. These videos, recorded at the annual singing at Mt. Lebanon Baptist Church in west Alabama on June 23, 2019, provide new virtual access to the experience of Sacred Harp's spatiality from a vantage point typically inaccessible to those who don't themselves lead songs.

Introduction

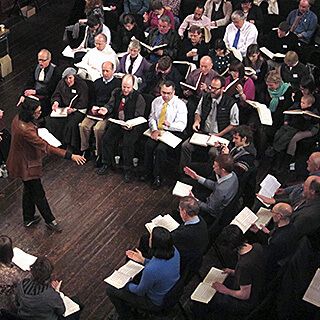

Sacred Harp singing is defined by its spatial organization as much as by its musical style. In this form of shape-note music, an assembled "class" of singers gathers at annual events called "singings"—weekend days spent in churches or community centers singing songs from The Sacred Harp, a nineteenth-century Georgia tunebook revised every generation or so. The tunebook uses a pedagogical system in which the music's note heads have four distinct shapes corresponding to their position in the scale, associated with the names "fa," "sol," "la," and "mi," which singers recite before singing a song's hymn text. Just as important as the shape-notes to the Sacred Harpers is the "hollow square" orientation in which singers sit, facing each other in rows of pews or chairs organized by voice part (bass, alto, treble, and tenor). Throughout the singing day, a procession of leaders take turns stepping into the hollow center to face the tenor or lead section that carries the melody and direct the class in a song or two of their choice from The Sacred Harp.1For more on Sacred Harp singing, see, especially, Buell E. Cobb Jr., The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989); John Bealle, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997); Kiri Miller, Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008); David Warren Steel and Richard H. Hulan, The Makers of the Sacred Harp (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010).

For singers, the hollow square is both a practically necessary convention and a deeply meaningful space. Encircled by full-voiced singing to hymn texts such as Isaac Watts's "Within Thy circling pow'r I stand, On ev'ry side I find Thy hand," for singers the immersiveness of the hollow square comes to represent God's encompassing love.2"Akin," music by P. Dan Brittain (1971), words by Isaac Watts (1719), in Hugh McGraw et al., eds., The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition (Carrollton, GA: Sacred Harp Publishing Company, 1991), 472. For composers, the spatial organization of singings, especially the separation of voice parts, is something to consider and emphasize in writing for the tradition. For singers and scholars seeking to capture the essence of Sacred Harp singings, the hollow square has been a longstanding focus, with advances in recording technology leading to new strategies. In this publication we introduce new immersive 360-degree video and audio recordings we made from within the hollow square in the summer of 2019 and offer context drawing on a larger project about the hollow square's meaning to singers and composers and the history of attempts to capture the experience of this unique sonic space.

Yi Halo and Ambeo VR at Mt. Lebanon

We used new video and audio recording technologies to capture elements of the experience of the hollow square. Our recording equipment included the Yi Halo, a device that captures video via seventeen separate cameras arranged in a circular housing. The Google platform Jump Assembler (now defunct) stitched the footage from all the cameras into a series of 360-degree videos.3Janko Roettgers, "Google Is Shutting Down Its Jump VR Video Program," Variety (blog), May 18, 2019, https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/google-jump-shutting-down-1203219306/. We used the Sennheiser Ambeo VR microphone to capture 360-degree spatial audio via four interconnected microphone capsules. Using the video editing application Adobe Premiere, we connected the 360-degree video to the spatial audio. When the user shifts the 360-degree visual field of view in the YouTube window, the audio shifts correspondingly. This spatial audio can only be experienced when wearing headphones.

After trying out the device at a Decatur, Georgia, all-day singing, we recorded three hours of the annual singing at Mt. Lebanon Baptist Church in rural Fayette County in west Alabama. This lively, midsize singing is in an area long central to the geography of what is now an international music culture with roots in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, and Texas.4On Sacred Harp's shifting geography, see James B. Wallace, "Stormy Banks and Sweet Rivers: A Sacred Harp Geography," Southern Spaces, June 4, 2007, http://southernspaces.org/2007/stormy-banks-and-sweet-rivers-sacred-harp-geography; Jesse P. Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing" (PhD diss., Emory University, 2015), https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/n009w256n?locale=en; Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn, "Mapping the 'Big Minutes': Visualizing Sacred Harp's Geographic Coalescence and Expansion, 1995–2014," Southern Spaces Blog (blog), January 23, 2018, https://southernspaces.org/2017/mapping-big-minutes-visualizing-sacred-harps-geographic-coalescence-and-expansion-1995-2014. The Mt. Lebanon Singing also serves as this Independent Baptist church's homecoming and as a reunion for the Ballinger family, a number of whose members are active singers. Today the singing also attracts members of singing communities in northeast Alabama, metro Atlanta, and further afield: singers in 2019 had traveled from New York City and Dublin, Ireland, to Fayette County. Trying the singers' patience and good humor, we placed the cumbersome, many-eyed Yi Halo in the singing's cozy hollow square for much of the day. Song leaders stood right next to the device. Steve captured conventional "flat" video from the back of the room, behind the tenor section, while Jesse sat and sang with the tenors.

The resulting recordings, embedded in this publication and accessible through YouTube, present video and audio from the center of the hollow square. This vantage point, typically inaccessible to those who don't lead songs, is the physical and spiritual center of Sacred Harp singings.

Entering the Hollow Square

The hollow square is central to understanding the music and music culture that surrounds The Sacred Harp. Singers associate the hollow square with key values of participation and community. Sacred Harp singers often state that they are "singing for each other and for God," rather than for an audience. Though non-singers such as family members and descendants of singers, congregants at churches hosting singings, and other curious individuals do sometimes come to listen, the layout of Sacred Harp singings, in which singers face each other rather than the listeners in the back, reinforces its participatory ethos.5On how Sacred Harp's spatial organization compares to that of historically related sacred music cultures, see Paula Tadlock, "Shape-Note Singing in Mississippi," in Discourse in Ethnomusicology: Essays in Honor of George List, ed. Caroline Card et al. (Bloomington: Ethnomusicology Publications Group, Indiana University, 1978), 191–207.

The hollow square also bolsters singers' sense of Sacred Harp as a community. Eye contact across the hollow square, where trebles face basses and tenors face altos, has kindled relationships, reinforced friendships, and intensified shared emotional experiences. Sacred Harp's music culture generally discourages talking while a singing is in session. In the absence of commentary on the affective and spiritual experience of singing, nonverbal communication—during singing and between songs as leaders cycle in and out of the square—contributes to singers' understanding of their experience as shared.6On verbal and nonverbal communication, the hollow square, and affective intensity in Sacred Harp singing, see Miller, Traveling Home; Kiri Miller, "'Like Cords Around My Heart': Sacred Harp Memorial Lessons and the Transmission of Tradition," Oral Tradition 25, no. 2 (2010), http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/oral_tradition/v025/25.2.miller.html; Anne Heider and R. Stephen Warner, "Bodies in Sync: Interaction Ritual Theory Applied to Sacred Harp Singing," Sociology of Religion 71, no. 1 (2010): 76–97.

The hollow square also improves the sound of Sacred Harp singings in ways both practically and aesthetically valued by singers. Facing each other makes it easier for singers to stay together. All can see and follow the leader, who beats time, moving an arm down and up to convey tempo. Singing at each other rather than out at an audience concentrates sound, making it easier for singers to hear each other. The accumulated volume enhances the depth of the experience.

Of course, the very best sound is in the center of the hollow square. In this space, the singing is loudest and all four parts achieve their best balance. Many singers who came to Sacred Harp singing as adults remember the first time they stepped into this space as the time they knew Sacred Harp singing would become an enduring part of their lives. Over time many come to think of this locus of Sacred Harp's spatial organization as a sacred space. Singers frequently invite newcomers to join them in the center for a song, believing that this is the best vantage point from which to apprehend what makes the music culture so moving to its participants.

Composing Sacred Harp's Spatiality

Many of the songs in The Sacred Harp leverage specific features of the hollow square for musical and emotional impact. The three immersive recordings of the Sacred Harp singing at Mt. Lebanon feature songs exemplifying two such approaches: fuging among the voice parts and traded high notes between the tenor and treble parts. Fuging tunes are among the most characteristic and popular song forms in The Sacred Harp. Typical fuging tunes begin with all the parts singing together, followed by a section in which each of the four voice parts enters in sequence, finally coming together again before the conclusion of the song.7Irving Lowens, "The Origins of the American Fuging Tune," Journal of the American Musicological Society 6, no. 1 (April 1, 1953): 46, https://doi.org/10.2307/829998. On fuging tunes, see also Karl Kroeger, American Fuging-Tunes, 1770–1820: A Descriptive Catalog (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994); Maxine Ann Fawcett-Yeske, "The Fuging Tune in America, 1770–1820: An Analytical Study" (PhD diss., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1997); Jesse P. Karlsberg, "Genre Spanning in the Close and Dispersed Harmony Shape-Note Songs of Sidney Whitfield Denson and Orin Adolphus Parris," American Music 35, no. 1 (2017): 94–132. The most common of these entrance patterns, as found in Jeremiah Ingalls's "New Jerusalem," led by Eli Hinton of Atlanta, Georgia, is propelled forward not just by the cascade of entrances and their progression from lower to higher voices, but by their spatialization. The entrance pattern proceeds counterclockwise around the hollow square, with basses followed by tenors, trebles, and altos.8"New Jerusalem," music by Jeremiah Ingalls (1796), words by Isaac Watts (1707), in McGraw et al., The Sacred Harp, 299.

Generations of composers have adopted this pattern and experimented with alternatives, frequently inspired by the arrangement of the vocal parts around the hollow square. After a short fuging section, Amos Munson's "Newburgh," led by Cheyenne Ivey, a member of a singing family from Henagar, Alabama, leverages the physical separation of the vocal parts to dramatize the celestial distance between the sun and stars. After the basses to the right of the leader enter on the phrase "Thou sun with golden beams" and all four parts sing "And moon with paler rays," the trebles, to the leader's left, reply with a shimmering "Ye starry lights, ye twinkling flames, Shine to your Maker's praise."9"Newburgh," music by Amos Munson (1798), words by Isaac Watts (1719), in McGraw et al., 182.

Composers also rely on the separation of vocal parts to create moments of power and energy by trading prominent high notes in rapid succession between the tenor and treble parts, a feature that singers often refer to as "thunder and lightning." Since these two parts are typically sung by mixed gender groups with similar vocal ranges, this trading back and forth of high notes would be undetectable without the vocal separation that the hollow square provides. In songs like C. Curtis's "Providence," led here by siblings Wanda Capps and Danny Creel from Dora and Hoover, Alabama, respectively, the traded high notes are distinct and clearly audible, contributing dynamic crackling energy to the song. "Providence" features "thunder and lightning" in multiple places. After a short opening section, the song's chorus begins with the trebles singing a musical phrase that peaks on a high note (accompanied by the basses) which is immediately echoed by the tenors. The song continues with similar exchanges, culminating in a figure ricocheting from the tenor to the treble as the song reaches its conclusion.10"Providence," music by C. Curtis (1820), words by Isaac Watts (1719), in McGraw et al., 298.

Recording the Hollow Square

For singers and scholars, Sacred Harp's spatial qualities have made recording the style appealing. Yet the results have persistently struck their makers and audiences as falling short of conveying the experience of being at a singing. The earliest field recordings, made by John W. Work III in 1938 and Alan Lomax and George Pullen Jackson in 1942, used then-available monophonic technology, collapsing the music's richly spatialized four-part harmonies to a single channel of recorded sound.

For Lomax, frustration with the result prompted him to include Sacred Harp singing in his itinerary for the "Southern Journey" field recording sessions he conducted in August through October of 1959 after he first gained access to portable stereo recording technology. The ensuing recordings, released in part as All Day Singing from "The Sacred Harp" (1961), provide considerably greater depth and intimacy than the monophonic recordings from the 1930s and 1940s, and contributed to greater public awareness of and interest in participating in Sacred Harp singing during the folk revival.11Alan Lomax and Alabama Sacred Harp Singers, All Day Singing from "The Sacred Harp," recorded 1959, 33 1/3 rpm record, Southern Journey (Bergenfield, NJ: Prestige, 1961). But Lomax's vantage point at one corner of the hollow square contributed to an imbalance among the parts that bothered contemporaneous Sacred Harp singers. The Sacred Harp Publishing Company, publisher of the most widely used tunebook at singings, responded by recording, producing, and releasing a series of LPs in the 1960s and 1970s, recorded in a studio and mastered to provide what they deemed a more satisfying balance of the parts.12Cobb, The Sacred Harp. When quadrophonic sound systems—one speaker for each Sacred Harp voice part!—proliferated in the 1970s, the same organization planned a release in this format, but the project was eventually shelved.

Conclusion

In the 2020s, as in the 1930s, there is no substitute for experiencing a Sacred Harp singing in person; singings today are held across the United States and beyond every weekend of the year. Yet we think the recordings of these three songs provide new virtual access to the experience of Sacred Harp's spatiality. We invite you to explore the activity in different parts of the singing space by shifting your perspective while navigating the video on your desktop monitor or your phone's YouTube app. If you wear headphones, you can hear the spatial audio shift along with the visual field of view. If you have access to a virtual reality headset, you can immersively experience the perspective these recordings afford. We plan to stage virtual reality viewings of these recordings at the Camp Fasola Sacred Harp singing school and at other singings in 2020. We will also make recordings of other songs accessible through the web in the coming months to expand the selection of songs and leaders captured using this technology.

Additional Videos

- Philip Gilmore, of Oneonta, Alabama, leads Ananias Davisson's "Idumea" (p. 47b) from The Sacred Harp.

- Ewa Lichnerowicz, of Dublin, Ireland, leads S. M. Denson's "Praise God" (p. 328) from The Sacred Harp.

- Cindy Tanner, of Henagar, Alabama, leads George Coles's "Green Street" (p. 198) from The Sacred Harp.

- Beth Wallace, Eady Porter, Aubrey Zeanah, and Ridley Colvin, of Fayette, Northport, and Demopolis, Alabama, lead O. A. Parris's "My Brightest Days" (p. 546) from The Sacred Harp.

- Judy Caudle, of Eva, Alabama, leads H. S. Rees's "Sweet Morning" (p. 421) from The Sacred Harp.

About the Authors

Steve Bransford is the senior video producer at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship. His documentary feature, The Well-Placed Weed, is available on Vimeo.

Jesse P. Karlsberg is the senior digital scholarship strategist at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship. He is the project director and editor-in-chief of Sounding Spirit, a research lab and publishing initiative promoting collaborative engagement with historical American songbooks. Karlsberg is an internationally recognized singer, teacher, composer, and songbook editor in the Sacred Harp tradition.

Recommended Resources

Text

Cobb, Buell E., Jr. The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989.

Heider, Anne, and R. Stephen Warner. "Bodies in Sync: Interaction Ritual Theory Applied to Sacred Harp Singing." Sociology of Religion 71, no. 1 (2010): 76–97.

Karlsberg, Jesse P. "Folklore's Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing." PhD diss., Emory University, 2015.

Miller, Kiri. "'Like Cords Around My Heart': Sacred Harp Memorial Lessons and the Transmission of Tradition." Oral Tradition 25, no. 2 (2010).

———. Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Steel, David Warren and Richard H. Hulan. The Makers of the Sacred Harp. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Web

Lomax, Alan. Stereo audio recordings of the United Sacred Harp Musical Association. Part of the Southern US 1959 and 1960 Collection. Association for Cultural Equity (New York, New York). September 1959. http://research.culturalequity.org/rc-b2/get-audio-ix.do?ix=recording&id=326&idType=sessionId&sortBy=abc.

Sabol, Stephen L. "Resources." Sacred Harp & Related Shape-Note Music. Last modified December 2, 2019. http://home.olemiss.edu/~mudws/resource.

Work III, John W. Mono audio recordings of southeastern Alabama Sacred Harp singers. Part of the John Work Collection of Negro Folk Music from the Southeast. American Folklife Center, Library of Congress (Washington, DC). 1938. https://www.loc.gov/search/?fa=partof:john+work+collection+of+negro+folk+music+from+the+southeast%7Ccontributor:sacred+harp+singers.

Similar Publications

| 1. | For more on Sacred Harp singing, see, especially, Buell E. Cobb Jr., The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989); John Bealle, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997); Kiri Miller, Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008); David Warren Steel and Richard H. Hulan, The Makers of the Sacred Harp (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010). |

|---|---|

| 2. | "Akin," music by P. Dan Brittain (1971), words by Isaac Watts (1719), in Hugh McGraw et al., eds., The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition (Carrollton, GA: Sacred Harp Publishing Company, 1991), 472. |

| 3. | Janko Roettgers, "Google Is Shutting Down Its Jump VR Video Program," Variety (blog), May 18, 2019, https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/google-jump-shutting-down-1203219306/. |

| 4. | On Sacred Harp's shifting geography, see James B. Wallace, "Stormy Banks and Sweet Rivers: A Sacred Harp Geography," Southern Spaces, June 4, 2007, http://southernspaces.org/2007/stormy-banks-and-sweet-rivers-sacred-harp-geography; Jesse P. Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing" (PhD diss., Emory University, 2015), https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/n009w256n?locale=en; Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn, "Mapping the 'Big Minutes': Visualizing Sacred Harp's Geographic Coalescence and Expansion, 1995–2014," Southern Spaces Blog (blog), January 23, 2018, https://southernspaces.org/2017/mapping-big-minutes-visualizing-sacred-harps-geographic-coalescence-and-expansion-1995-2014. |

| 5. | On how Sacred Harp's spatial organization compares to that of historically related sacred music cultures, see Paula Tadlock, "Shape-Note Singing in Mississippi," in Discourse in Ethnomusicology: Essays in Honor of George List, ed. Caroline Card et al. (Bloomington: Ethnomusicology Publications Group, Indiana University, 1978), 191–207. |

| 6. | On verbal and nonverbal communication, the hollow square, and affective intensity in Sacred Harp singing, see Miller, Traveling Home; Kiri Miller, "'Like Cords Around My Heart': Sacred Harp Memorial Lessons and the Transmission of Tradition," Oral Tradition 25, no. 2 (2010), http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/oral_tradition/v025/25.2.miller.html; Anne Heider and R. Stephen Warner, "Bodies in Sync: Interaction Ritual Theory Applied to Sacred Harp Singing," Sociology of Religion 71, no. 1 (2010): 76–97. |

| 7. | Irving Lowens, "The Origins of the American Fuging Tune," Journal of the American Musicological Society 6, no. 1 (April 1, 1953): 46, https://doi.org/10.2307/829998. On fuging tunes, see also Karl Kroeger, American Fuging-Tunes, 1770–1820: A Descriptive Catalog (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994); Maxine Ann Fawcett-Yeske, "The Fuging Tune in America, 1770–1820: An Analytical Study" (PhD diss., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1997); Jesse P. Karlsberg, "Genre Spanning in the Close and Dispersed Harmony Shape-Note Songs of Sidney Whitfield Denson and Orin Adolphus Parris," American Music 35, no. 1 (2017): 94–132. |

| 8. | "New Jerusalem," music by Jeremiah Ingalls (1796), words by Isaac Watts (1707), in McGraw et al., The Sacred Harp, 299. |

| 9. | "Newburgh," music by Amos Munson (1798), words by Isaac Watts (1719), in McGraw et al., 182. |

| 10. | "Providence," music by C. Curtis (1820), words by Isaac Watts (1719), in McGraw et al., 298. |

| 11. | Alan Lomax and Alabama Sacred Harp Singers, All Day Singing from "The Sacred Harp," recorded 1959, 33 1/3 rpm record, Southern Journey (Bergenfield, NJ: Prestige, 1961). |

| 12. | Cobb, The Sacred Harp. |