Overview

This essay explores the history, geography, and contemporary practices of Sacred Harp—one form of a cappella, shape-note music—in the US South. The roots of Sacred Harp extend back to an eighteenth-century New England singing-school movement that spread the rudiments of choral music south and west with songs that drew upon folk melodies as well as original compositions by the earliest American composers. The Sacred Harp, a songbook compilation that gave its name to the major stream of shape note music, has remained in continuous use and revision since its publication in 1844. Sacred Harp singing took its strongest hold outside the southern plantation regions, especially in the piedmont and upcountry, encouraged by performance practices that represented a more egalitarian ethos. Although considered by most participants to be a form of worship, Sacred Harp exists independently of official denominational support and welcomes anyone interested in singing. This essay also considers the imagined geographies evoked by Sacred Harp through its lyrics and examines the tradition’s distinct configuration of sacred space.

"Stormy Banks and Sweet Rivers: A Sacred Harp Geography" is part of the 2008 Southern Spaces series "Space, Place, and Appalachia," a collection of publications exploring Appalachian geographies through multimedia presentations.

Introduction

On a warm Saturday in early summer, a crowd gathers at a white-washed church in rural Alabama. As they begin to sing, a sound rises that is overwhelming in volume and intensity. The lyrics speak of the transience of life on earth and express a longing for a more joyous existence in the next world. The music has a haunting quality, with plaintive tones and a sound that to the uninitiated might seem more at home in medieval or renaissance Europe than in the US South. The crowd will sing from 9:30 in the morning until about three in the afternoon, and they will use only one songbook—The Sacred Harp.

| C major scale in shape notes, four-shape system of the Sacred Harp. (From Wikipedia) |

| Sacred Harp "Rudiments" from 1911 edition of the Original Sacred Harp. Image courtesy of Emory University Pitts Theology Library. |

| What gives Sacred Harp singing its haunting, ancient sound? In Sacred Harp music, the tenor part may carry the melody, but each of the other parts (bass, alto, treble) have important roles. Composers also make use of parallel fifths, in which an interval of a fifth is employed consecutively, and Sacred Harp composers consider two notes, often fifths, sufficient for a chord. Sacred Harp music includes unique performance practices. For example, all songs are sung loudly. Participants sing virtually at the top of their voices, though the falling and rising of the leader's arm can indicate where accents should be placed. Music composed in this style may feature dispersed harmony, in which the parts cross over each other rather than running parallel. Both the tenor and treble sections include men and women, creating the effect of a six-part, rather than a four-part, harmony. Sacred Harp music frequently includes fuging tunes, which incorporate a technique similar to singing in rounds. The different parts enter at different intervals as they repeat a line. |

History of Sacred Harp

| Title page of the fourth edition of The Sacred Harp, published in 1870. Image courtesy of Emory University Pitts Theology Library. |

The name of this oblong songbook has come to designate the form of a cappella choral music it preserves. Sacred Harp music has its beginnings in New England music reforms. Puritans neglected sacred music, and by the late seventeenth century, many church-goers were weary of antiquated psalmody and a limited number of tunes. Singing schools emerged to teach lay-persons the basics of reading and performing music. These schools operated independently of any congregation or denomination and were run by itinerant teachers who were often self-taught in music (Pen 212). With a revived interest in church music, composers introduced new tunes that ignored European "scientific" musical theory and broke many of the rules of Western musical composition. One of the most famous of these singing masters was William Billings (1746-1800), a Boston tanner who composed some of the earliest American music.

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, musicians in northeast urban centers became enamored of European styles of composition and came to regard the kind of music taught in the singing schools as crude. Musicians such as Lowell Mason (1792-1872) began an ardent campaign against the singing schools and the kind of music they promoted. Mason and the "better music" advocates helped insure that European standards would be the basis of the musical curriculum in public schools.

The singing school migrated south and west. Although critics pursued the tradition (Lowell Mason's brother, Timothy, moved to Cincinnati (Bealle, 29)), it put down firm roots in regions of the South. As immigrants moved southward from Pennsylvania into Virginia and the Carolinas, singing masters and their singing schools followed. The Shenandoah Valley proved fertile ground. (Cobb 1989, 66). Singing schools and gatherings provided a social institution much appreciated by rural farmers. The schools' success increased the demand for tune books.

Sometime around 1798, William Little and William Smith of Philadelphia compiled The Easy Instructor, likely published in Albany, New York (for problems of dating and place of publication, see Metcalf, 89-97; Lowens and Britton, 115-37; Bealle 269, n. 1). This compilation of primarily American music incorporated shape-notes, or patent-notes, for the first time. To make sight-reading easier, a unique shape was assigned to each of the four syllables (fa, sol, la, and mi) commonly used to represent the seven-note scale (fa, sol, la, fa, so, la, mi). This system became popular for use both in the singing schools and in songbooks. Although numerous books were printed with shape notes, none have had the staying power of The Sacred Harp.

| A page from the 1850 edition of B. F. White's and E. J. King's The Sacred Harp. The title, "Northfield," refers to the tune on which the arrangement is based and not to the lyrics of the hymn. Image courtesy of Emory University Pitts Theology Library. |

Although originally published in Philadelphia in 1844, The Sacred Harp was compiled and edited by Benjamin Franklin White and E. J. King (ca. 1821-1844) in Hamilton, Georgia. It thrived especially around the foothills of the Appalachians that stretch into northern Georgia and Alabama, and accrued strong followings in parts of northern Mississippi and some locales of Tennessee as well. George Pullen Jackson speculated in 1944 that "aside from the Holy Bible, the book found oftenest in the homes of rural southern people is without doubt the big oblong volume of song called The Sacred Harp" (Jackson 1944, 7). Although other song books continued to be printed using shape-notes, most eventually adopted the seven-shape system (representing the seven syllables do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti), and after the mid-nineteenth century, the tunes in these books came to be increasingly influenced by gospel styles.

The Spaces of Sacred Harp

|

| Mt. Zion Methodist Church, Mt. Zion, GA, July 2005. Image courtesy of Matt and Erica Hinton. |

The Sacred Harp and the American music it preserves have survived. Not only did the singing school persist in regions of the South, but another social institution developed to carry Sacred Harp music forward — the singing convention. Conventions would last several days and bring together the faithful, many traveling several days to attend. Since rural congregations were often served by circuit riders who rotated through a group of churches, it proved easy to find an empty building for a weekend of singing, despite the lack of official denominational support.

Sacred Harp found a special ally in the Primitive Baptists who resisted the modernization of church music (Cobb 1989, 5). To this day, many singings are held in Primitive Baptist churches, though Methodist and Missionary Baptist churches are frequently used. In addition to the larger conventions, which persist in a slightly altered form, regular local singings are scheduled, usually on the same day each year (for example, the third Sunday and prior Saturday in March), and often at the same location.

| Empty church with pews arranged for Sacred Harp singing. Wilson's Chapel, site of the Chattahoochee Convention (the oldest annual Sacred Harp convention), Carrolton, GA, August 2005. Image courtesy of Matt and Erica Hinton. |

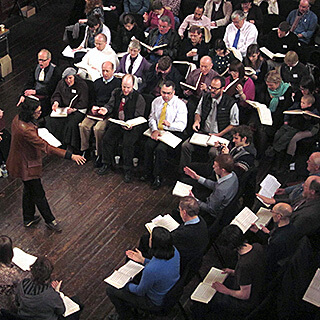

The arrangement of space within the church expresses the emphasis that singers place on participation. In a typical Protestant church, row after row of pews face a pulpit or lectern, and the choir faces the congregation. For a Sacred Harp singing, however, the seating resists any suggestion that a divide might exist between "performer" and "audience." The people sit in four sections. Altos face tenors, and trebles face basses. This arrangement of singers forms a hollow square in the center. In this square stands a leader. Throughout the day, participants will take turns leading one or two songs (see: "Leading Sacred Harp Music"). Anyone, young or old, male or female, with basic competence in the music is encouraged to take a turn leading. Time permitting, everyone who wants to lead will get a chance.

Leading a song means far more to Sacred Harp singers than the opportunity to select a favorite piece of music. Standing in the hollow square, the leader is at the center of the space where all the sound converges. Singers consistently emphasize that the experience of the music is most powerful from the hollow square.

|

| Reba Dell Windom leads "Schenectady," at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church, Bremen, GA, June 2004. Image courtesy of Matt and Erica Hinton. |

The rotation of song leaders throughout the day suggests the democratic impulses at the heart of the tradition. Sacred Harp music caught on most strongly in areas inhabited by yeoman farmers rather than those places in the South dominated by large plantations. The minutes kept by the early singing conventions reveal attention to democratic process (Cobb 1989, 130-32). The music is sung a cappella; the "Sacred Harp" refers to the human voice raised in song. Since everyone has this sacred harp, participation is open to all. The songs themselves have deep roots among the folk. Many of the tunes and some of the lyrics that made it into The Sacred Harp were the compositions of unschooled farmers who sang the music, and today, some devotees continue to compose using original principles and practices. Other songs derive from the improvised group singings that occurred at camp meetings (Cobb 1989, 79-83; Pen 217).

Although the lyrics of many songs come from the pens of Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, and John Newton, tunes may be the work of a farmer recalling fiddle melodies (Pen 217; Cobb 1989, 73-74; for more detail on this topic, see Horn). Ultimately, tracing the authorship of songs in The Sacred Harp is tricky business, since many of the ascriptions are inaccurate. A composer might avoid his or her own name out of modesty and choose to dedicate the song to another by using the other person’s name.

Sacred Harp singers use a narrow range of dynamics — every song should be loud. And with their unique performance practices comes a distinct taste in performance spaces. Singers prefer the small, wooden, country churches similar to those that would have nourished this music in its infancy. The walls are unadorned, surfaces should be hard, and the floors should not be carpeted. A square building with relatively low ceilings serves the acoustical tastes of these singers better than vaulted ceilings (Pen 226). Concert halls engineered for modern tastes may be used at times or for special performances, but they are not preferred.

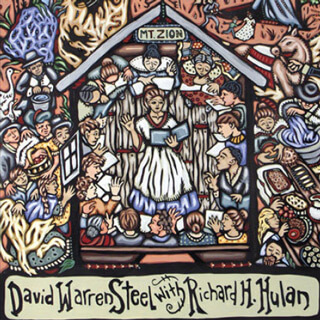

Sacred Harp singers do not spend the entire day inside the confines of the church. Around midday they break for dinner on the grounds. Spread over several tables, a sumptuous potluck meal, usually eaten outside, awaits the singers. Mississippi artist Ethel Mohamed vividly captured images of activities both inside and outside the church building through her embroidery and reminiscences.

When a singing is held at a rural church, the cemetery on the church grounds often becomes another focal space, especially for singers with local ties. Singings often coincide with the homecoming of a congregation or family, when the widely dispersed return to renew acquaintances and pay tribute to ancestors by decorating their graves (see: "Sacred Harp Singings"). Just before or after dinner on the grounds, singings often feature a "memorial lesson," during which songs are dedicated to the memories of the singers who have died in the last year. Some annual singings are dedicated to deceased stalwarts of the tradition.

| Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church, Bremen, GA, June 2004. Image courtesy of Matt and Erica Hinton. |

The vast majority of Sacred Harp songs have spiritual themes, and for most participants, singings are a form of worship. However, The Sacred Harp occupies an ambivalent space in the religious world. By the express intention of the original compiler, B. F. White, the songs are meant to be compatible with any denomination, and statements of singing conventions echo this sentiment (Cobb 130). The singing schools exist as a social and religious institution separate from any formal denominational support. Singings frequently occur on Saturdays, or take advantage of a church building's being empty on Sunday if its part-time minister serves another congregation.

Many Harps

Despite the value placed on continuity with "the old paths," the living Sacred Harp boasts local variety. Although the Denson revision of The Sacred Harp is by far the most popular, two other revisions maintain followings, especially where the shape-note tradition was somewhat late spreading. The Cooper book is used especially in western Florida and the lower regions of Alabama and Mississippi, as well as in parts of Texas. The White book is used in some singings in east Atlanta and northwest Georgia (Cobb 1989, 6-7).

| Map of Cooper Book Usage | Map of White Book Usage |

The Southern Harmony published in 1835 by William Walker is another four-shape book still in use. It has served as the songbook for only one long-standing annual singing held in Benton, Kentucky, but it has recently been picked up at some new singings. In 1866, Walker published a seven-shape songbook entitled Christian Harmony. This book included recent hymns and reflected the influence of gospel-style music. It remains the staple of numerous singings in North Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama (see: The Christian Harmony Singings). Some Sacred Harp singers will include a song or two from the Christian Harmony at their own singings. Christian Harmony is one of several seven-shape books that remain in use.

|

| Frontispiece of The Colored Sacred Harp, 1934. Image courtesy of Emory University Pitts Theology Library. |

There also exists an African American Sacred Harp tradition, primarily in northwestern Florida and southeast Alabama, as well as in northern Mississippi and eastern Texas (Cobb 1989, 6). Most Black Sacred Harp singers use the Cooper book; however, those in northern Mississippi prefer the Denson book (Cobb 1989, 7). (For an essay on Black Sacred Harp singing in Mississippi, see: Chiquita Walls's "Mississippi's African American Shape Note Tradition." On African American Sacred Harp singing in East Texas, see: Donald R. Ross's "Black Sacred Harp Singing in East Texas.") Black Sacred Harp singers of the “Wiregrass” region of southeast Alabama supplement the Cooper book with The Colored Sacred Harp, a short tune-book that contains music written by African American composers. (source: "Tunebooks, Music and Hymnals"; "Judge Jackson and the Colored Sacred Harp"; also Willett 50-55. All songs are by Black composers with the single exception of "Eternal Truth Thy Word" by Bascom F. Faust, a white banker who put up one thousand dollars to help subsidize the publication of the book; Willett 53.)

| Map of Wiregrass Region of Alabama | Areas of Black Sacred Harp Activity |

| African American Sacred Harp Audio: "Wiregrass Sacred Harp Singers" (10:27 min.) This program in the Folkways Radio Series features musical performances along with discussion by singing masters Japheth Jackson and Dewey Williams, and Williams's daughter, Bernice Harvey. From the Folkways radio series courtesy of Alabama Center for Traditional Culture. |

| Image of Wiregrass Singers from Alabama Center for Traditional Culture. |

Sacred Harp as Folk Tradition

Is Sacred Harp a folk tradition? On the one hand, it exists in a published form. The music and words are preserved in a songbook. However, many of the tunes collected in The Sacred Harp derive from folk melodies passed down aurally before being written (cf. Cobb 1989, 73-74). Varieties of styles and the differences from region to region reflect the importance of local preferences. For example, Black Sacred Harp singers have developed styles so unique that, according to Cobb, the prospects for "consolidation" with white singers are slim (Cobb 1989, 6). Even among white singers united by the use of the Denson book, stylistic differences exist depending upon location (on the question of Sacred Harp as a folk tradition, see especially Bealle).

| The Wootten family of the Sand Mountain region in Alabama has helped to preserve the Sacred Harp tradition for many generations. In this photo, Terry Wootten leads a song at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church in Bremen, GA. The Wootten Family, with Terry Wootten leading, performed most musical selections included in this essay ("Pisgah" is performed by the Wiregrass Sacred Harp Singers). Image courtesy of Matt and Erica Hinton. |

|

| Map of the Sand Mountain Region |

Many of the audio selections in this piece are performed by the Wootten family, most of whom live in north Alabama. Many hail from the Sand Mountain region, especially the communities of Ider and Henagar. Sacred Harp singers know the Wootten family for their distinct style of leading. If a song is in 4/4 time, the leader will wave his or her hand left and right at the bottom of the down-stroke to account for all the beats, rather than using the simpler up and down motion which most leaders employ (Cobb 1995, 42). The Woottens also tend to sing slowly.

Sacred Harp and the Pastoral

For all of their evocation of tradition, place, family, friends, and good food, Sacred Harp singers face the transience of earthly life without illusions:

So fades the lovely blooming flow'r,

— Anne Steele, "Distress," The Sacred Harp (1991), 32b.

Frail, smiling solace of an hour;

So soon our transient comforts fly,

And pleasure only blooms to die.

Song after song in The Sacred Harp expresses longing for the next life, frequently designated "Canaan" and celebrated as a heavenly promised land. Rooted in Biblical descriptions, the geography of Canaan is depicted as a peaceful land of lush vegetation and gentle, flowing rivers where families and friends reunite permanently and all sorrows cease. By contrast, this present life is a tangled wilderness or the stormy banks of the Jordan River, which one must cross:

Sweet rivers of redeeming love

A few more days, or years at most,

Lie just before mine eyes,

Had I the pinions of a dove,

I'd to those rivers fly;

I'd rise superior to my pain,

With joy outstrip the wind,

I'd cross o'er Jordan's stormy waves

And leave the world behind.

My troubles will be o'er;

I hope to join the heav'nly host

On Canaan's happy shore.

My raptured soul shall drink and feast

In love's unbounded sea;

The glorious hope of endless rest

Is ravishing for me.

— John Adam Granade, "Sweet Rivers," The Sacred Harp (1991), 61.

"The Promised Land" includes the lyrics:

On Jordan's stormy banks I stand,

And cast a wishful eye

To Canaan's fair and happy land

Where my possessions lie.

O the transporting, rapt'rous scene

That rises to my sight!

Sweet fields arrayed in living green,

And rivers of delight.

Filled with delight, my raptured soul

Would here no longer stay!

Though Jordan's waves around me roll,

Fearless I'd launch away.

— Samuel Stennet, The Sacred Harp (1991), 128.

The pastoral imagery of these songs may further explain why they have maintained loyalty from rural people during generations of migration and urbanization.

Conclusion

Sacred Harp joins sacred sound with sacred space in a sociable event. From the printed pages of The Sacred Harp, musical space is negotiated by means of relative pitch to accommodate the range of the day's singers. Songs typically provide each part (bass, tenor, alto, treble) with a good musical line to sing. The physical space of Sacred Harp singing is arranged so that the center of worship is where all voices converge. The hollow square orients this space; its center is where the music is experienced in the balance of voices and at its loudest. Entrance into this inner sanctuary requires no ordination, nor are there restrictions based on age, race, or gender in current practice. Adherence to specific creeds or the lack of formal profession of Christian faith does not restrict access. The sacred does not inhere in an altar, a sacrament, or a church building. The priority is that the room be "live" and conducive to the sound. Where they gather, the singers create the space.

The uniqueness of Sacred Harp space evokes its origins in colonial American singing schools which sought to broaden musical education. By mid-nineteenth century, shape note music had lost out in northern urban areas to more modern styles. The 1844 publication of The Sacred Harp signified the successful migration of the music and the singing school to white yeoman-farming areas in several southern regions. Although early on the leading of songs tended to be restricted to male singers who were proficient in the music (Cobb 1989, 142-43), Sacred Harp singings welcomed participants from any protestant denomination. During the Jim Crow era, African American singers developed a distinctive Sacred Harp style that continues today. The egalitarianism at the heart of the tradition may help explain the resurgence in popularity that this music has enjoyed. New singers, especially in urban areas or on university campuses where traditional styles are unfamiliar, easily learn to sing together.

The physical structures where singers have sung Sacred Harp have helped shape their musical tastes. Veterans prefer square, wooden buildings such as rural churches and schoolhouses. The pastoral lyrics provide continuity between many participants' rural experience and the image of heaven the songs describe. And, although the tradition is portable, many of the sites for annual singings become touchstones for dispersed individuals and families. The notion of "homecoming" suggests a return while implying the dispersions and disruptions of modernity and urbanization.

For years confined to the US South, Sacred Harp singings are now held throughout the country, from Florida to Washington, from California to Maine. Outside of the southeast, singings are especially prominent in New England and in the states along the West Coast, as well as in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan [see 2004 Singings Map ]. England is home to frequent singings, and singings can be found in eastern Canada. The Sacred Harp is open to any and all willing to seek out the hollow square.

| Prof. Don Saliers leads at Cannon Chapel, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, February 2005. Image courtesy of Patrick Graham. |

About this Essay

Most of the sound clips in this essay feature the Wootten family from the Sand Mountain region of Alabama. These performances aired in 1995 on the radio show Folk Masters, recorded at the Barns of Wolf Trap in Vienna, Virginia, and produced and hosted by folklorist Nick Spitzer. I am indebted to Matt and Erica Hinton for images from their documentary Awake My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp, and to Matt for teaching me about this music. For additional images from the excellent collection of Sacred Harp hymnals and materials found in the Emory University Pitts Theology Library, I am grateful to Patrick Graham, John Weaver, Debra Madera, the staff of Special Collections and Archives and for the Robert W. Woodruff Library Fellowship which enabled me to research and write this essay.

About the Author

James B. Wallace is a PhD candidate in New Testament Studies in the Graduate Division of Religion at Emory University.

Recommended Resources

Online Bibliographies

Shape Note Bibliography — by John Bealle

This extensive bibliography includes works directly related to Sacred Harp as well as works helpful for establishing its historical and religious context; the bibliography is particularly strong on Protestant hymnody.

http://fasola.org/bibliography/index.html

Sweet Is the Day: Bibliography and Links

This short bibliography lists the standard works on Sacred Harp music and provides a Wootten Family discography.

http://www.folkstreams.net/context,62

Articles and Essays on Sacred Harp Singing

Warren Steel's compilation of links to online essays and articles also includes practical, how-to essays related to Sacred Harp and reviews of books and recordings.

http://www.mcsr.olemiss.edu/~mudws/articles/

Links

Sacred Harp Singing

The official website of the Sacred Harp Musical Heritage Association, this website includes general information about Sacred Harp singing and provides easy access to lists and minutes of singings.

http://fasola.org/

Sacred Harp Singing

Warren Steel's site offers insight into numerous aspects of Sacred Harp and features both scholarly articles and basic question-and-answer about Sacred Harp music. Steel also keeps an updated list of Sacred Harp singings that occur throughout the United States, England, and Canada.

http://www.mcsr.olemiss.edu/%7Emudws/harp.html

Sacred Harp & Related Shape-Note Music: Resources

This website, maintained by Steven L. Sabol, boasts numerous short descriptions of tune books, books related to Sacred Harp, and especially sound and video recordings.

http://www.mcsr.olemiss.edu/~mudws/resource/

Introduction to Sacred Harp Music

Wikipedia's article serves as an excellent introduction to Sacred Harp music.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_Harp

Awake My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp

Far more than an advertisement for the documentary Awake My Soul (see below), this site includes an excellent essay on the history and practice of Sacred Harp, along with brief biographies of some key figures.

http://www.awakemysoul.com/

Video Documentaries

Awake My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp.

Directed by Matt and Erica Hinton. Produced by Matt Hinton. Awake Productions, 2006.

A beautiful documentary that captures the sights and sounds of Sacred Harp singing, Awake My Soul is one of the best introductions to the history and contemporary practice of Sacred Harp.

(http://www.awakemysoul.com/)

Sweet is the Day: A Sacred Harp Family Portrait.

Directed by Jim Carnes. Produced by Erin Kellen. The Alabama Folklife Association, 2001.

Sweet is the Day documents the Wootten Family of Sand Mountain, Alabama, who have preserved and promoted Sacred Harp music for many generations.

(http://www.folkstreams.net/film,44)

Print Materials

Bealle, John. Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong. University of Georgia Press: Athens, 1997.

Boyd, Joe Dan. Judge Jackson and The Colored Sacred Harp. Montgomery, Ala.: Alabama Folklife Association, 2002.

Boyd, Joe Dan. "Judge Jackson: Black Giant of White Spirituals."Journal of American Folklife 83 (1970), 446-451.

Cheek, Curtis Leo. "The Singing School and Shape-Note Tradition: Residuals in Twentieth-Century American Hymnody." PhD diss. University of Southern California, 1968.

Cobb, Buell E. The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. Athens, GA: Brown Thrasher Books/University of Georgia Press, 1989.

Cobb, Buell E. "Sand Mountain's Wootten Family: Sacred Harp Singers," in Henry Willett (ed.), In the Spirit: Alabama's Sacred Music Traditions. Montgomery, AL: Black Belt Press, 1995, 40-49.

Dyen, Doris Jane. "New Directions in Sacred Harp Singing," in W. Ferris and M.L. Hart (eds.), Folk Music and Modern Sound. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 1982, 73-79.

Dyen, Doris Jane. "The Role of Shape-Note Singing in the Musical Culture of Black Communities in Southeast Alabama." PhD diss. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1977.

Ellington, Charles Linwood. "The Sacred Harp Tradition of the South: Its Origin and Evolution." PhD diss. Florida State University, 1969.

Hardaway, Lisa Carol. "Sacred Harp Traditions in Texas." Masters thesis. Rice University, 1989.

Horn, Dorothy D. Sing to Me of Heaven: A Study of Folk and Early American Materials In Three Old Harp Books. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press, 1970.

Jackson, George Pullen. The Story of the Sacred Harp 1844-1944: A Book of Religious Folk Song as an American Institution. Nashville: Vanderbilt Press, 1944.

Jackson, George Pullen. White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands: The Story of the Fasola Folk, Their Songs, Singings, and "Buckwheat Notes." Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933.

Kelton, Mai Hogan. "Analysis of the Music Curriculum of 'Sacred Harp' (American Tune-Book, 1971 Edition) and Its Continuing Traditions." PhD diss. University Alabama, 1985.

Marini, Stephen A. Sacred Song in America: Religion, Music, and Public Culture. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Metcalf, Frank J. "'The Easy Instructor': A Bibliographical Study." The Musical Quarterly 23 (1937), 89-97.

Pen, Robert. "Triangles, Squares, Circles, and Diamonds: The 'Fasola Folk' and Their Singing Tradition," in Kip Lornell and Anne K. Rasmussen (eds.), Musics of Multicultural America: A Study of Twelve Musical Communities. New York: Schirmer Books, 1997, 209-232.

Tallmadge, William H. "The Black in Jackson's White Spirituals." The Black Perspective in Music 9 (1981), 139-160.

Willett, Henry. "Judge Jackson and the Colored Sacred Harp," in Henry Willett (ed.), In the Spirit: Alabama's Sacred Music Traditions. Montgomery, Ala.: Black Belt Press, 1995, 50-55.