Overview

Drawing on the comprehensive records of over four thousand Sacred Harp singings across the globe, Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn trace the geographical transformations of this a capella musical culture from 1995 to 2014. Mapping the proceedings at annual singings in the visualization platform Carto reveals the persistence of robust clusters of Sacred Harp participants within and beyond the southern United States, complicating overdetermined narratives of Sacred Harp's northern expansion and southern decline in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Three of the eleven interactive maps are embedded within the text; the remaining eight are linked within the text and listed at the end of this blog post.

Blog Post

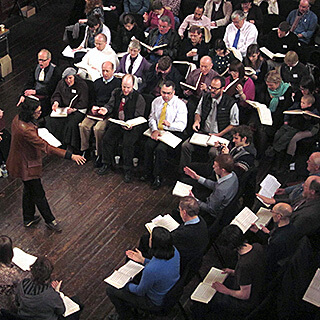

The Sacred Harp, a shape-note tunebook first published in 1844, has long been the center of a network of "singing conventions," weekend meetings featuring a cappella harmony singing at which participants take turns leading an informally assembled group in singing selections from the book. Beginning with singings in Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Texas during the second half of the nineteenth century, participation in Sacred Harp has been tied to local, church, and kinship networks.1George Pullen Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands: The Story of the Fasola Folk, Their Songs, Singings, and "Buckwheat Notes" (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933); Buell E. Cobb, The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989); David Warren Steel, The Makers of the Sacred Harp (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010). In the twentieth century, however, The Sacred Harp's geography shifted to reach beyond these contexts. Scholars frequently recount the contours of these shifts in broad strokes bound up in narratives tied to folksong rhetoric and southern romanticism.2John Bealle, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997); Kiri Miller, Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008). As the style came to be characterized as a folk music and included in American music curricula on college campuses in the second half of the twentieth century, singings spread to the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast. Later, through these same channels, The Sacred Harp expanded to Canada, Europe, Australia, and East Asia.3Jesse P. Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing" (Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 2015), http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/pgtds; Ellen Lueck, "Sacred Harp Singing in Europe: Its Pathways, Spaces, and Meanings" (Ph.D. dissertation, Wesleyan University, 2016). Meanwhile, journalists and individuals across Sacred Harp's geography associated the style with "old-fogy" rural southern white culture in decline and regularly foretold the style's extinction in the southern states where it first thrived.4For examples and analysis of Sacred Harp singers' negotiation of the "old-fogy" label, see George Pullen Jackson, The Story of The Sacred Harp, 1844–1944: A Book of Religious Folk Song as an American Institution (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1944); Hugh W. McGraw, "'There Are More Singings Now Than Ever Before': Hugh McGraw Addresses the Harpeth Valley Singers," Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 3 (December 31, 2013), http://originalsacredharp.com/2013/12/31/there-are-more-singings-now-than-ever-before-hugh-mcgraw-addresses-the-harpeth-valley-singers; Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter," 105–12.

In this post we complicate these narratives, drawing on a newly augmented database of the proceedings at thousands of Sacred Harp singings in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, adding nuance and specificity to the story of Sacred Harp's recent geographic transformations. Minutes, summaries of the proceedings at annual Sacred Harp singings, constitute an integral part of this music culture. Elected or appointed secretaries originally published minutes in pamphlets or spread them through local newspapers. After World War II, rural depopulation caused local singing networks to contract, while improved infrastructure facilitated travel. During this time, a publication known colloquially as the "Big Minutes" grew out of the minutes pamphlets of a network of singings centered in Winston County, Alabama.5Editors of today's "Big Minutes" repeat the received history that the book originated as the minutes pamphlet of the Alabama State Sacred Harp Musical Convention, based in Birmingham, Alabama. However, minutes pamphlets in the collections of Winston County, Alabama, singers Roma Rice and Margaret Keeton, and the Carrolton, Georgia, Sacred Harp Museum, suggest that this Winston County-centered publication was the precursor to today’s “Big Minutes”; continuities in printer, editor, and singings between a set of 1930s and early 1940s minutes pamphlets for a group of singing conventions centered in Winston County, Alabama, and pamphlets published beginning in 1945 titled Minutes of the Alabama-Tennessee Sacred Harp Singing Conventions, and, after 1954, titled Minutes: Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee Sacred Harp Singings, indicate a shared lineage. Today the "Big Minutes" are comprehensive: nearly all annual singings using the most common edition of The Sacred Harp disseminate their minutes through the volume. The "Big Minutes" contain appendices including contact information and birthdays for thousands of active singers, lists of singers who have died in the past year, and a directory of upcoming singings for the year. Still, the bulk of its contents are dedicated to documenting each singing held the previous calendar year.

These minutes for individual Sacred Harp singings are remarkable documents, providing a granular record of the musical taste and activities of each participant in this decentralized music culture. Minutes detail the name of each song leader, the page number(s) of song(s) each person led, the names of officers and committee members, these committees' reports, and even the timing of lunch and recesses. They also include information about the location of each singing, most often listing the city or town, state, and name of the church or other building where the singing was held.

In 1995, a non-profit organization, the Sacred Harp Musical Heritage Association (SHMHA), assumed responsibility for the minutes and adopted a digital process enabling more streamlined production of annual print volumes and the publication of a searchable database.6To access this database or order a print copy of the contemporary "Big Minutes," see Judy Caudle, et al., eds., "Minutes and Directory of Sacred Harp Singings," Fasola.org, http://fasola.org/minutes/. Projects such as the FaSoLa Minutes iOS and Android app and the "Song Use in The Sacred Harp" statistics page on Fasola.org draw on the availability of the minutes in digital form to enable analysis of song use and leader behavior.7On the FaSoLa Minutes app, see Clarissa Fetrow, "There's an App for That: A Review of the 'FaSoLa Minutes' App," Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 3, no. 2 (November 12, 2014), http://originalsacredharp.com/2014/11/12/theres-an-app-for-that-a-review-of-the-fasola-minutes-app/. Thanks to its inclusion of location information, the minutes database also suggests the possibility of visualizing the geographical development of Sacred Harp over the past twenty years.

Our new mapping of Sacred Harp singings—drawing on minutes data—required enhancing the database used to publish the annual volumes. We began with data from 4,173 singings using The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition held between January 1995 and December 2014.8Mark T. Godfrey created this dataset for the FaSoLa Minutes app and with Jesse P. Karlsberg supported Robert A. W. Dunn's research augmenting the data with precise locations. Godfrey's original dataset features enhancements to the SHMHA data and excludes 740 singings using other Sacred Harp editions and related shape-note books. These singings were initially excluded to ensure that page numbers included in the minutes reliably indexed specific songs in The Sacred Harp. The exclusions also improve the representativeness of the minutes, which feature nearly all annual singings from The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition, but relatively few singings from other tunebooks, which typically disseminate their minutes through other publications. An array of variations from year to year and from singing to singing presented problems in creating a unified dataset. For example, different secretaries responsible for taking minutes at these singings adopted disparate approaches to the level of detail in naming singing locations.9Most secretaries include the names of buildings where singings are held, but others give names of larger institutions or campuses with multiple potential venues. A handful of singing minutes feature no specific location, instead providing just a city or town and county. Other minutes include a city or town but no county, or a county but no municipality. Additionally, a singing may undergo changes from year to year, as the building in which it was located may change names or the singing may move to a different location entirely, all while keeping the same singing name. Mapping the minutes required consistently adopting naming conventions found within the minutes so that each singing was given a building name, city/town, county, and state.

However, the majority of the work involved locating data not found in the minutes book. Through using a combination of web-based mapping services (such as Google Maps, Google Street View, MapQuest, and HERE), contacting dozens of singers who helped organize singings with hard-to-pin-down locations, and taking one field trip to a log cabin in Winston County, Alabama, we identified exact locations of all but thirty-one singings, complete with street names and numbers and, most importantly, GPS coordinates. This unified dataset with precise location data makes visualizing Sacred Harp's geographical shifts over the past twenty years possible to an unprecedented extent. The global timeline map (below) displays the locations of singings held each year between 1995 and 2014 in sequence.

Global Sacred Harp Singings, 1995–2014

Global Sacred Harp Singings, 1995–2014. Interactive Map by Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn. View larger version.

The growth of Sacred Harp singings in Europe from a single annual event in England to a dense cluster with additional singings scattered across the continent, and the establishment of a singing in Australia, are perhaps the most noticeable of all changes on this world map. Even at this scale, changes within the United States, such as the increase in the density of singings in the Northeast and on the West Coast, are also visible.

Many more changes to the United States' singing geography are observable on a more regional scale. The zone stretching from West Georgia to West Alabama reveals a hotbed of Sacred Harp singing dating from the nineteenth century. Noticeable shifts are apparent between 1995 and 2014. These changes affirm that singings have ceased to be held in some counties, yet demonstrate that strong networks persist in other areas, undercutting the overdetermined narrative of the decline of southern singings. Our visualizations demonstrate that what began in 1995 as a solid strip of singings stretching across this area of the Alabama and Georgia upcountry had by 2014 coalesced into discrete spatial clusters. Interconnected networks of singings persisted in Walker, Winston, and Cullman Counties north of Birmingham; in northeast Alabama; and on the Alabama-Georgia border in Cleburne County, Alabama, and Haralson, Carroll, and Heard Counties, Georgia.

Alabama and Georgia Upcountry Sacred Harp Singings, 1995–2014

Alabama and Georgia Upcountry Sacred Harp Singings, 1995–2014. Interactive Map by Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn. View larger version.

In the Birmingham and Atlanta metropolitan regions, the number of singings has held steady even as their geography has shifted, revealing nuance obscured by the overarching narrative of southern decline. In Birmingham, the number of annual singings remains constant while their locations move out of the city center (view interactive map). In Atlanta, singings held in north Fulton County are steadily supplanted by those held towards the center of DeKalb County (view interactive map).

The visible growth of Sacred Harp singings in southern states outside of historical singing areas, perhaps most noticeable in South Carolina (view interactive map) and Arkansas (view interactive map), undercuts the binaristic opposition of growth in the North and decline in the South. Before 1999, there were no Sacred Harp Singings held in South Carolina. By 2011, there were four annual singings held across the state. Arkansas, at its peak, featured three singings, none of which were held in 1995. (The state presently features two.)

Mapping minutes data also adds specificity to the story of Sacred Harp's expansion to other parts of the United States. Popular narratives date the style's expansion as occurring in the 1970s and 1980s, in the immediate aftermath of Sacred Harp's incorporation into the folk revival. Yet the mapping of minutes data reveals a later acceleration of the style's spread beyond the South in the 1990s and 2000s. No annual singings were held in Pennsylvania in 1995, yet singings proliferated in the eastern part of the state over the subsequent two decades, and spread to the central and western part of the state from 2008 to 2010 (view interactive map). Eight singings were held in Pennsylvania in 2014. Sacred Harp singing also grew steadily in the Pacific Northwest, from one singing in the mid- to late 1990s, to seven annual singings in 2014 (view interactive map). Even in New England, where the oldest continuously held annual singing outside the South celebrated its fortieth anniversary in the fall of 2016, mapping the minutes reveals a dramatic expansion from a single annual singing in 1995 to eleven events in 2014 (view interactive map).

New England Sacred Harp Singings, 1995–2014

New England Sacred Harp Singings, 1995–2014. Interactive Map by Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn. View larger version.

Visualizing the changing geography of singings from The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition also demonstrates shifts in the balance of singing from different Sacred Harp editions and the growing comprehensiveness of the "Big Minutes" compilation. In Texas, where singings generally feature the descendant of a competing early-twentieth-century revision of The Sacred Harp known as the "Cooper Book," mapping reveals the inroads made by the 1991 Edition in the state, growing from two singings in 1995 to six singings in 2014 (view interactive map).10On the social context of the increasing number of singings from the 1991 Edition in Texas since the 1990s, see Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter," 118–24. The increase in singings in the area of middle and south Georgia around Macon and Thomaston (view interactive map) and in east central Alabama near Alexander City is due to the decision of longstanding networks of singings from the 1991 Edition that continued to publish their own separate minutes pamphlets to affiliate with the "Big Minutes" in the late 1990s and early 2000s.11The South Georgia Convention, a network of a dozen singings from the 1991 Edition centered around Macon and extending south to Cordele, Georgia, continues to publish an annual minutes pamphlet, even as its sponsored singings increasingly submit minutes to the "Big Minutes."

Our augmentation of born-digital Sacred Harp minutes data dating back to 1995 affords an unprecedented look at the extent to which the use of The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition has shifted in the past two decades, complicating popular narratives of the style's northern spread and southern decline. A team of volunteers is currently processing digitized minutes from fifty annual volumes going back to 1945, produced prior to the digitization of the minutes' production process, part of a plan to expand the database that we augmented to create these maps.12For more on this process and a collection of research drawing on the expanding Sacred Harp minutes database, see "Sacred Harp Minutes: Querying Sacred Harp's Sonic Past through the Minutes of Sacred Harp Singings, 1945–2016," 2017, http://fasolaminutes.org/. We hope this marks the beginning of the process of drawing insights from the extraordinarily comprehensive and granular record of participation in a music culture that the Sacred Harp minutes provide.

Additional Maps

- Metro Birmingham (Alabama)

- Metro Atlanta (Georgia)

- South Carolina

- Arkansas

- Pennsylvania

- Pacific Northwest

- Texas

- South Georgia

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chris Thorman, Mark T. Godfrey, and Judy Caudle for their assistance obtaining and editing minutes data and Megan Slemons, Stephanie Bryan, and the rest of the Southern Spaces staff, for their assistance producing this post.

About the Authors

Jesse P. Karlsberg is the Senior Digital Scholarship Strategist at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship and the consulting editor of Southern Spaces. A scholar of digital publishing and American music, Jesse is the editor of Original Sacred Harp: Centennial Edition (Pitts Theology Library and Sacred Harp Publishing Company, 2015). His 2015 dissertation, "Folklore's Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing," earned honorable mention for the Society of American Music's Wiley Housewright Dissertation Award.

Robert A. W. Dunn is a music and historical research consultant for the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship’s Sounding Spirit project. He is a Sacred Harp singer and musician and graduated in 2016 from Emory University with a BA in History and Music.

Cover Image Attribution:

Sacred Harp singing minutes volumes in the collection of the Sacred Harp Museum. Photograph by Jonathon Smith.Recommended Resources

Text

Cobb, Jr., Buell E. The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989.

Filene, Benjamin. Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Knowles, Anne Kelly. Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS are Changing Historical Scholarship. Redlands, CA: ESRI Press, 2008.

Malone, Bill C. and David Stricklin. Southern Music/American Music. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1979.

Steel, David Warren and Richard H. Hulan. The Makers of the Sacred Harp. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Web

"Online Mapping for Beginners." Carto. Accessed May 23, 2017. https://carto.com/academy/courses/beginners-course.

Sabol, Stephen. "Resources." Sacred Harp & Related Shape-Note Music. Accessed May 23, 2017. http://home.olemiss.edu/~mudws/resource/.

"Sacred Harp." Southern Georgia Folklife Collection. Valdosta State University Archives and Special Collections. Accessed May 23, 2017. http://archives.valdosta.edu/folklife/sacredharp.html

Snow, Melinda. "The Sacred Harp." New Georgia Encyclopedia. April 6, 2005. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/sacred-harp

White, B. F., E. J. King and J. S. James, eds. Original Sacred Harp, 1911. Theology Reference Collection, Readux. Emory University. Accessed May 23, 2017. http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/r8qzb.

Similar Publications

| 1. | George Pullen Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands: The Story of the Fasola Folk, Their Songs, Singings, and "Buckwheat Notes" (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933); Buell E. Cobb, The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989); David Warren Steel, The Makers of the Sacred Harp (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010). |

|---|---|

| 2. | John Bealle, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997); Kiri Miller, Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008). |

| 3. | Jesse P. Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing" (Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 2015), http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/pgtds; Ellen Lueck, "Sacred Harp Singing in Europe: Its Pathways, Spaces, and Meanings" (Ph.D. dissertation, Wesleyan University, 2016). |

| 4. | For examples and analysis of Sacred Harp singers' negotiation of the "old-fogy" label, see George Pullen Jackson, The Story of The Sacred Harp, 1844–1944: A Book of Religious Folk Song as an American Institution (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1944); Hugh W. McGraw, "'There Are More Singings Now Than Ever Before': Hugh McGraw Addresses the Harpeth Valley Singers," Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 3 (December 31, 2013), http://originalsacredharp.com/2013/12/31/there-are-more-singings-now-than-ever-before-hugh-mcgraw-addresses-the-harpeth-valley-singers; Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter," 105–12. |

| 5. | Editors of today's "Big Minutes" repeat the received history that the book originated as the minutes pamphlet of the Alabama State Sacred Harp Musical Convention, based in Birmingham, Alabama. However, minutes pamphlets in the collections of Winston County, Alabama, singers Roma Rice and Margaret Keeton, and the Carrolton, Georgia, Sacred Harp Museum, suggest that this Winston County-centered publication was the precursor to today’s “Big Minutes”; continuities in printer, editor, and singings between a set of 1930s and early 1940s minutes pamphlets for a group of singing conventions centered in Winston County, Alabama, and pamphlets published beginning in 1945 titled Minutes of the Alabama-Tennessee Sacred Harp Singing Conventions, and, after 1954, titled Minutes: Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee Sacred Harp Singings, indicate a shared lineage. |

| 6. | To access this database or order a print copy of the contemporary "Big Minutes," see Judy Caudle, et al., eds., "Minutes and Directory of Sacred Harp Singings," Fasola.org, http://fasola.org/minutes/. |

| 7. | On the FaSoLa Minutes app, see Clarissa Fetrow, "There's an App for That: A Review of the 'FaSoLa Minutes' App," Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 3, no. 2 (November 12, 2014), http://originalsacredharp.com/2014/11/12/theres-an-app-for-that-a-review-of-the-fasola-minutes-app/. |

| 8. | Mark T. Godfrey created this dataset for the FaSoLa Minutes app and with Jesse P. Karlsberg supported Robert A. W. Dunn's research augmenting the data with precise locations. Godfrey's original dataset features enhancements to the SHMHA data and excludes 740 singings using other Sacred Harp editions and related shape-note books. These singings were initially excluded to ensure that page numbers included in the minutes reliably indexed specific songs in The Sacred Harp. The exclusions also improve the representativeness of the minutes, which feature nearly all annual singings from The Sacred Harp: 1991 Edition, but relatively few singings from other tunebooks, which typically disseminate their minutes through other publications. |

| 9. | Most secretaries include the names of buildings where singings are held, but others give names of larger institutions or campuses with multiple potential venues. A handful of singing minutes feature no specific location, instead providing just a city or town and county. Other minutes include a city or town but no county, or a county but no municipality. |

| 10. | On the social context of the increasing number of singings from the 1991 Edition in Texas since the 1990s, see Karlsberg, "Folklore's Filter," 118–24. |

| 11. | The South Georgia Convention, a network of a dozen singings from the 1991 Edition centered around Macon and extending south to Cordele, Georgia, continues to publish an annual minutes pamphlet, even as its sponsored singings increasingly submit minutes to the "Big Minutes." |

| 12. | For more on this process and a collection of research drawing on the expanding Sacred Harp minutes database, see "Sacred Harp Minutes: Querying Sacred Harp's Sonic Past through the Minutes of Sacred Harp Singings, 1945–2016," 2017, http://fasolaminutes.org/. |