Overview

Michael Bibler explores the "real precarity and messiness of what it means to be human" in the twenty-first century through the "unique story" of John B. McLemore, the voice at the center of the recent podcast S-Town. Although sympathetic to McLemore’s unique and powerful voice, Bibler argues the form of the "podcast ultimately restricts [it]," and in so doing reifies unimaginative ideological assumptions of southern queerness.

Queer Intersections / Southern Spaces is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that explore, trouble, and traverse intersections of queer experiences, past, present, and future. From a variety of perspectives, and with an emphasis upon the US South, this series, edited by Eric Solomon, offers critical analysis of LGBTQ+ people, practices, spaces, and places.

The largest proportion of LGBTQ+ Americans—thirty-five percent—live in the southeastern states from Maryland and West Virginia down to Texas and Oklahoma.1Amira Hasenbush, Andrew R. Flores, Angeliki Kastanis, Brad Sears, and Gary J. Gates, "The LGBT Divide: A Data Portrait of LGBT People in the Midwest, Mountain, and Southern States," The Williams Institute, December 2014, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/lgbtdivide. Yet, arguably the most recognized queer person from the South in our time—that is to say, the person whose queer identity is most famously associated with his southern identity—is deceased. And he was already deceased when he became such an unlikely celebrity in 2017. I am talking about John B. McLemore, the subject of the wildly popular podcast S-Town. Given the historical visibility of queer communities and activism in New York, Chicago, and California, it is somewhat understandable that the national imaginary continues to picture LGBTQ+ people as living mostly in the urban centers of the North and West. What is it about McLemore that gained him so much international attention? Of all the other queer people within that southern plurality, why him? And why does it matter that he reached that fame only when he was already dead?

Like most listeners, I'm sure, what I love best about S-Town is McLemore's irrepressible character and voice. McLemore was an antique horologist and self-described "semi-homosexual" who lived in Bibb County, Alabama, outside the small town of Woodstock. However, although Woodstock is only about thirty miles equidistant from the metropolitan centers of both Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama's largest city, the podcast deceptively portrays the area as excessively rural and remote. That deception not only gets this part of Alabama wrong, but also perpetuates a longstanding stereotype of the whole South as generally disconnected from the modern world, culturally and geographically. I should confess here that I am ultimately not a fan of S-Town, and this portrayal is just part of the reason why.

Nevertheless, McLemore's unique story still offers a rich opportunity to examine the complex dynamics of sexuality, gender, race, and class at the fringes of the more familiar, metronormative centers of urban queer life. McLemore was a paranoid genius, with the rare ability to see and explain all the invisible connections between his immediate locality and the global forces of capitalism, inequality, war, and environmental degradation currently destroying the planet. Sadly, in addition to other likely causes, including the mercury poisoning he probably contracted from his work on antique clocks, McLemore's paranoia drove him to suicide on June 15, 2015. This loss makes me doubly grateful that Brian Reed, S-Town's creator and narrator, decided to share McLemore's voice with millions of listeners. In a time when so many people happily treat every new music video, online commentary, Presidential tweet, and podcast like S-Town as a revolutionary event, McLemore resists any easy classification or commodification and shows us, instead, the real precarity and messiness of what it means to be human, as well as queer and southern, in the twenty-first century.

In her excellent article about S-Town, Monique Rooney examines the way that McLemore's untimely "voice from beyond the grave" combines with the "intermedia" of other texts and objects within the podcast—including "clocks and sundials," the "elaborate hedge maze that John created, unrecorded conversations, letters, a novel and other print narratives, poetry, songs, film, e-mails, Google maps, theatrical rituals, tattoos and tattooing, texts messages and graffiti"—to create a queerly alternative sense of time that works within and against the linear structure of the overarching narrative form.2Monique Rooney, "Queer Objects and Intermedial Timepieces: Reading S-town," Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 23, no. 1 (2018): 157. This intermedial structure of text and paratext, she argues, "opens the listener to wider networks and spheres" beyond "John's relentlessly caustic and negative views of life in the American South" and offers McLemore himself as "an intermediary" who "confound[s] . . . established hierarches and conventional subject/object relations," especially in terms of temporality, region, and sexuality.3Rooney, 159.

While there's no denying the power of McLemore's voice, I believe that the podcast ultimately restricts that power by constraining it within the closed temporal field of the podcast's strictly sequential form. Although Rooney argues that "S-Town's queerly intermedial form counteracts its ends-driven sequential form and its death-driven themes," the podcast's relentless push toward narrative resolution still wins out.4Rooney, 157, original emphasis. Moreover, while McLemore's recorded voice may be coming "from beyond the grave," his death still means that he can never speak out after the podcast to confront its selective portrayal of him. McLemore is endlessly complex, yet he will never be more complex than the narrative allows. This containment helps explain how he has become a figure of so much public fascination: like any dead celebrity, he can never finally reassert his subjectivity in a way that might change our perceptions and fantasies about him. And this restrictive framework is what frustrates me most about S-Town, for I know that I can never fully separate the McLemore I have come to like from the McLemore that Reed has edited for us.

Other reviewers have challenged Reed's serious ethical problem of seeming to exploit McLemore's death for creative and financial gain.5Jessica Goudeau, "Was the Art of S-Town Worth the Pain? How a Decades-Old Literary Argument Adds Insight to the Debate over the Popular Nonfiction Podcast," The Atlantic, April 9, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/04/was-the-art-of-s-town-worth-the-pain/522366/; Aja Romano, "S-Town is a stunning podcast. It probably shouldn't have been made," Vox, April 1, 2017, https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/3/30/15084224/s-town-review-controversial-podcast-privacy. Around the same time that plans for a movie adaptation were announced in June 2018, McLemore's estate filed suit against the makers of the podcast for violating his "rights of publicity."6EJ Dickson, "Judge Allows Lawsuit to Proceed Against 'S-Town' Podcast Makers," Rolling Stone, March 25, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/s-town-lawsuit-john-mclemore-estate-812965/. But I want to consider another ethical concern in the way that Reed manipulates McLemore's voice to produce a certain effect—or rather, affect—for his listeners. Even as S-Town lets us experience McLemore's unusual character directly, this story of his troubled genius and premature death packages his character in a way that implicitly makes us, the listeners, feel different from him, no matter how much we might personally identify with him. As narrator, Reed uses McLemore to imagine a pleasanter, happier type of subjectivity, fashioning himself as a model liberal subject—not necessarily liberal in the pedestrian sense, although he does that too, but in the sense of being a self-contained, autonomous individual who appears, unlike McLemore, more or less separate from, and unaffected by, all the disciplinary and controlling forces of society. In addition, the podcast invites listeners to identify with Reed's narrative voice, eventually sharing his feelings of transcendent mobility and sophistication in opposition to the pain and paranoia that we hear in McLemore. Reed's aural embodiment of this liberal subject position promises listeners a similar sense of freedom and survival in a world of heightened global uncertainty—the forces that McLemore constantly railed against.

This buffering effect is, I think, another part of what gives S-Town its widespread appeal. Of course, it's not necessarily bad or unusual that a creative work would help us find this sense of pathos and security in a troubled world. But what I don't like is the way that Reed creates this affect by figuratively sacrificing McLemore to a worn narrative of southern gothic dysfunction. To create this twenty-first-century subjectivity that seems to transcend place, S-Town traps McLemore hopelessly and eternally in the place that he calls Shittown, Alabama. Although Reed ends the podcast with the story of McLemore's birth, S-Town buries him forever at the clichéd, lonely crossroads of a tragically (never happily) queer and backwards South. And in doing so, no matter what else the podcast might tell us about the real-life experience of being a queer, white, "semi-homosexual" man in semi-rural Alabama, this narrative framework reveals much more about the ideological uses served by mainstream imaginaries of southern queerness—fantasies of what it means to be queer and southern, southern and queer—in twenty-first-century US culture and beyond.7Brian Reed, "Chapter II: Has Anybody Called You?" March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 44:22, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/2. If any movie adaptation were to try to elicit the same kind of feeling in its viewers, I can't imagine it would be any less exploitative.

Policing the South

There's no denying S-Town's popularity. All seven episodes were made available for download on March 28, 2017, and since then tens of millions of listeners have followed Reed's account of McLemore's life and suicide. S-Town establishes itself, much like Reed's prior work, Serial, as a true-crime investigation. McLemore has asked Reed to investigate two things—an alleged murder and a case of alleged police corruption—and Reed sets to work combing the police reports and interviewing locals, although he didn't visit Alabama until a year later.

In Chapter I, Reed establishes a not-so-subtle conflation between Alabama and an imagined picture of the "South" as a whole. He does this in part by overstating the rurality of the setting. For example, Reed's description of where he stays on his first visit to Alabama invokes broader tropes of a sparsely populated, isolated landscape: "I had to leave Bibb County to find a hotel, so I'm in Bessemer, a small city about fifteen miles down the highway, where the far reaches of the Birmingham Metro Area dissolve into the rural counties like Bibb to the west. I'm at a Best Western just off the exit ramp, behind a Waffle House."8Brian Reed, "Chapter I: If You Keep Your Mouth Shut, You'll Be Surprised What You Can Learn," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 31:16, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/1. While fifteen miles on an interstate highway hardly makes a marathon drive into the "far reaches" of civilization (and why does he have to "find" the hotel, as if the internet, a map, or McLemore himself, hadn't already told him where it was?), Reed effectively "dissolves" the specific landscape of Alabama into a more symbolic landscape of rural counties "like" Bibb whose generic southernness is made all the more evident by their common location "behind a Waffle House."

In Chapter II, Reed determines that rumors about the murder McLemore asked Reed to investigate were exaggerated tales of a fight that occurred at a party "in the middle of the woods" in Tuscaloosa County.9Reed, "Chapter II," 22:48. Reed's attention to the fact that the fight took place in the woods once again occludes the proximity of Tuscaloosa and Birmingham. Reed mentions the quick arrival of the police and ambulance, as well as the nearness of a hospital where the alleged murderer Kabram Burt was taken to treat his injuries after the fight, and the fact that Burt called a friend in Bessemer, which is outside Birmingham, to pick him up at the hospital. Nevertheless, Reed gives the last word about the fight to Burt, who shrugs off the incident as the normal consequence of "liv[ing] like white trash and shit," and the rumors of murder as a normal consequence of living in "a damn small town, man."10Reed, "Chapter II," 26:43, 25:28. Although Reed essentially "solves" the crime for his listeners, he uses Burt's testimony to blur the scene of the crime with a broader notion of southern rurality. The fight might have happened anywhere in this imagined South, because the only spaces that matter here are a gossipy small town and a wooded landscape dominated by "white trash," not the more metropolitan adjacent spaces.

Construing the semi-rural setting of S-Town as excessively rural sets the stage for Reed's portrayal of McLemore as a queer loner who is similarly isolated, the apparent lawlessness of the place echoing the turbulent, anything-but-normal life of this particular inhabitant. And so, just after his explanation to McLemore about the fight, Reed quickly turns to the news of McLemore's suicide, even though in real time McLemore's death occurred several months after that conversation. Squeezing this sequence of events allows Reed to maintain the "true crime" format of the podcast, and he quickly sets to work exploring the details of McLemore's death and the fallout that ensues.

Thankfully, Reed is not entirely interested in solving the question of what finally led McLemore to take his own life. From a literary standpoint I am glad he didn't oversimplify things by trying to pin down a single, simple cause or motive. Based on this narrative open-endedness, I would agree with reviewer Katy Waldman that S-Town looks and sounds like a new kind of literary genre, what she calls "aural literature."11Katy Waldman, "The Gorgeous New True Crime Podcast S-Town is Like Serial but Satisfying," Slate, March 30, 2017, http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2017/03/30/s_town_the_new_true_crime_podcast_by_the_makers_of_serial_reviewed.html. Yet, where she argues that this new kind of true-crime literature is "even more satisfying because [the case] always stays open," I believe that this feeling of audience satisfaction stems from something that is ideologically more dubious than open-endedness—and that shows how "aural literature" may not be so new after all. For all its novelty, and for all the ways that the podcast's intermedial elements stand "at odds with the sequential form," as Rooney writes, I find that this podcast has much in common with the traditional novel.12Rooney, 157. It deviates from the path of standard-fare detective stories and police procedurals, but detection and policing remain central to the narrative, both figuratively and structurally, thus replicating many of the discursive effects of discipline and control that literary critic D.A. Miller has identified in British novels of the Victorian era.13D.A. Miller, The Novel and the Police (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988).

Miller demonstrates how Victorian novels use narratives of policing and investigation to establish a covert model of self-policing and self-discipline for the unmarked, bourgeois center of society. These novels, he argues, set up a "scene" of criminality and/or social dysfunction (e.g., the slums of Victorian London) as a space that requires rigorous investigation. The narrative intrusion into this scene establishes its opposite. By going into a dysfunctional space and then withdrawing, the novel constructs and "repairs . . . normality" as a space "not needing the police or policelike detectives."14Miller, The Novel and the Police, 3. Moreover, this pattern defines the structure of the Victorian novel beyond tales of explicit crime and detection. To borrow the words from Dickens's novel Our Mutual Friend (1864–65), Miller adapts the work of Foucault to show how these texts "do the police in different voices," deploying all kinds of modes of discipline, surveillance, and constraint to make the reader a good, orderly subject for the sake of a stable, orderly society. In the narrative restoration of "normality," the protagonist (who, like Reed, is sometimes the narrator) is able to forget or disavow the "system of carceral restraints or disciplinary injunctions" that shape his subjectivity.15Miller, The Novel and the Police, x. And so, by way of our identification with that narrator/character, we readers can forget the disciplinary regimes that govern our "normality," too, because our implicit acquiescence to those regimes similarly means that no visible intervention or investigation is required. When the disciplinary structures of society seem most invisible, we liberal subjects feel like we're free of them.

In S-Town, following McLemore's lead, Reed constructs an imaginary, emphatically rural, and corrupt "Alabama" (as well as a wider "South") full of violence, racism, theft, and intrigue—exactly the kind of "scene" that requires this sort of literary "intrusiveness." Although the podcast starts with a specific investigation into the local circumstances of the alleged murder, Reed blurs that literal act of investigation with subtler forms of exposure and containment when he turns to McLemore's suicide, widening the scope of the figurative investigation beyond the local to McLemore's fraught position within sectional, national, and global contexts. In particular, I want to delve into two aspects of the podcast where Reed performs this novelistic policing: his treatment of Alabama racism and his treatment of McLemore's queerness. Both depictions construct Alabama and the wider South as a backwards, dysfunctional space in need of heavy policing, literally and figuratively. And it is through this clichéd sectional portrayal that we can most clearly understand how Reed exploits McLemore to construct this version of the liberal subject.

The Backwards South, Again

Thankfully, because this is a podcast delivered through sound, and not a written narrative, the power and originality of McLemore's voice constantly break through Reed's efforts to shape what we hear. But then S-Town squanders this opportunity by editing McLemore's voice to fit a more shopworn "southern" script. Like Jeeter Lester soaking his feet in the drainage ditch in Erskine Caldwell's Tobacco Road (1932), it doesn't take long before S-Town sinks into a stream of southern gothic clichés. Yes, Reed is following McLemore's cynical lead, but Reed seems even more insistent in portraying Shittown as backwards and corrupt and runs with McLemore's own comparison of Shittown to the "undercurrent of depravity" expressed in William Faulkner's story "A Rose for Emily" (1930).16Reed, "Chapter I," 32:50. And, even though Reed also mentions similar works by writers Guy de Maupassant and Shirley Jackson, he uses the Zombies' song inspired by "A Rose for Emily" as the closing music for every episode, underscoring connections between the podcast and southern gothic literature.17Literary critics David A. Davis and Gina Caison discuss these southern gothic tropes at length, including the comparison to Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily." Hear their excellent critique on the podcast "S02 Episode 3: Gilded Souths & S-Towns," July 20, 2017, in About South, produced by Gina Caison, Kelly Vines, and Adjoa Danso, podcast, MP3 audio, 38:27, https://soundcloud.com/about-south/s02-episode-3-gilded-souths-and-s-towns.

In later chapters, we learn that McLemore allegedly buried large amounts of gold on his property, and Reed turns us into narrative prospectors by making us wonder if the gold was found by greedy relatives, stolen by the police, or, as Reed implies, dug up in the middle of the night by McLemore's neighbor and most intimate companion in the podcast, Tyler Goodson. As with other elements of this true-life story, the legend of buried gold is of McLemore's making. But, in the telling of it, Reed can't seem to recognize what A Streetcar Named Desire's Blanche Dubois (1947), Queen Diva of the southern gothic, would have noticed in a heartbeat: that the story of buried gold is so old that "Only Poe! Only Mr. Edgar Allan Poe!—could do it justice!" Although Blanche references Poe's poem "Ulalume" (1847) in the play, where the poet visits his dead lover's grave, in this context I'm talking about Poe's 1843 short story about buried pirate treasure, "The Gold Bug."18The story of southerners obsessively digging up land in the search for buried gold also echoes the plot of Caldwell's farcical God's Little Acre (1933).

Finally, there's S-Town's closest literary parallel: John Berendt's popular Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994). I wasn't much of a fan of that, either. Both works cast their nonfictional gaze upon a supposedly insular "southern" place and regale their audience with sensational, almost shocking "discoveries" of things like actual gay people! and even more complicated gender dynamics! Here are places, they announce, plagued with racism! and full of crimes of passion! where half the locals are too secretive and the other half are far too garrulous! Even things like college football and getting a tattoo start to sound like arcane rituals. In other words, these texts spectacularize all the colorful, grotesque things you might find virtually anywhere else in these United States, southern stereotypes be damned. To me, there's just not much that's very new in the manner of this podcast's representation. From Berendt to Blanche to Faulkner to Poe, S-Town tells a story we've been hearing for a long time.

Clichés are necessary to Reed's portrayal of a gothic South that needs policing. Like the Victorian novel, S-Town constructs an image of Alabama as the place where disorder and depravity reign. In fact, it is so dysfunctional that even the police need policing. Remember that McLemore's initial email to Reed asked for help investigating not only the alleged murder, but also a case of police corruption. And later, when Reed considers that the police might have stolen McLemore's gold when they first arrived on the suicide scene, McLemore's cousin Reta Lawrence returns to this question of corruption: "Isn't that what John first got in touch with me about to investigate, she says, corruption in the local police?"19Brian Reed, "Chapter V: Nobody'll Ever Change My Mind About It," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 16:10, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/5. Maybe the police did steal the gold. But Reed doesn't actually need to solve any of these questions. As satisfying as it is that all the cases are "left open," as Katy Waldman argues, Reed also needs his southern setting to remain gothic and corrupt in order to create the implicit counterexample of a "normal" world where the police aren't corrupt and a "normal," bourgeois person needn't worry about such things.

Another way that Reed bolsters this extended stereotype of the gothic South is through his treatment of race and racism. When Reed visits a tattoo parlor in Chapter II, he takes pains to point out the racism of the young men in the room, as if any listener could miss it. Reed seems to want to shock listeners, presumably by broadcasting what they might not normally hear in public discourse, at least before the 2016 Presidential campaign, but also by confirming that the old figuration of a racist South needs no qualifications or nuances. What's really shocking, however, is Reed's blatant, and rather clumsy, attempt to distance himself from these white men ideologically and geographically. Reed does nothing to confront or complicate the unexamined whiteness of both his real-life subjects and his own perspective.20Wesley Jenkins, "The Empathy of 'S-Town' Doesn't Extend to Black People," BuzzFeed News, April 21, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/wesleyjenkins/the-empathy-of-s-town-doesnt-extend-to-black-people?utm_term=.fmJA3Xxxe#.jtpwXLBBz; Maaza Mengiste, "How 'S-Town' Fails Black Listeners," Rolling Stone, April 13, 2017, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/how-s-town-fails-black-listeners-w476524. He quietly tells one of the young men that racism in New York is "quieter" than it is in the South.21Reed, "Chapter II," 8:34. And then, in case we had any doubts, Reed assures his audience that he is certainly not a racist, for he has boldly, bravely taken the step of making all his social media accounts private to prevent his interviewees from seeing a photo of him with his future wife, Solange, who's black.22Reed, "Chapter II," 7:58.

Surely Reed can't really believe that these young men are so disconnected from the rest of the world that they wouldn't be able to google his name and find out more. Even bigots in Alabama have smartphones, as McLemore laments at length in Chapter I. I think Reed actually has a different motive for telling us about his social media accounts, for in doing so he positions himself as different from these other white men in important ways. By reminding us that his fiancé is black, Reed telegraphs that he is a nonracist, liberal subject who is much more connected to the modern world, not just in terms of internet savvy, but also in terms of politics. By reminding us that where he hails from racism is allegedly "quieter" (what would Eric Garner say about such a claim?), Reed suggests that he is much less tied to place than the other whites in that tattoo parlor—that he is much more mobile culturally, economically, ideologically, and geographically. Reed's unmarked whiteness allows him to travel in and out of different spaces, while the marked racism of the other white men will, it seems, prevent them from fitting in anywhere else than sweet home Alabama. With a little digital pruning, Reed will be OK in Shittown, but those boys will never make it in New York.

By layering racism, subjectivity, and place onto each other in this way, Reed also puts listeners in the same liberal subject position as himself. We implicitly identify with his narrative voice as he marks those other subjects as different and flawed. Reed wants us to feel that we, like him, are not constrained by our time and place, even if the racism where we live isn't actually "quieter." Reed's narrative manipulations tell us that we, as untethered individuals, must be liberal in the more pedestrian sense, too. Unlike those white Alabamans who don't seem to question or notice that K3 Lumber, their local lumber mill, implicitly honors the Ku Klux Klan, as Reed suggests at the very beginning of Chapter I, our feeling of autonomy—accentuated by the disembodiment of the aural podcast—guarantees we'll never have a problem with Brian Reed's marriage to Solange.23Reed, "Chapter I," 18:38.

A Queer South

Reed makes similar moves in the way he discusses McLemore's sexuality. Another thing I like about this podcast is the way that McLemore and his relationships defy simplistic analysis or categorization. The most complicated, and the one to which Reed gives the most airtime, is McLemore's close intimacy with his younger neighbor, Tyler Goodson. As McLemore admits in Chapter V, and as we learn more fully in Chapter VI, their relationship may seem to others more like a "usership" than a "friendship" because of the men's codependencies.24Reed, "Chapter V," 49:09. McLemore gives Goodson money and other kinds of material support, ostensibly for all the odd jobs he performs, while Goodson reciprocates with emotional and physical companionship. There is no clear indication that they had sex, but the erotic, even romantic dimensions of their relationship are unambiguous. Goodson agrees to satisfy McLemore's apparent fetish for pain by regularly tattooing his skin, including his nipples, and even whipping him. And, just before his death, the two men spray-paint their names on a local bridge like a queer combination of teenage lovers and, since they did this on Father's Day, daddy and son.25Reed, "Chapter VI: Since Everyone Around Here Thinks I'm a Queer Anyway," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 50:36, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/6.

Here is a rich opportunity for mapping some of the unlikely networks of gender, power, and pleasure that shape all those sketchy spaces beyond more familiar queer metropoles such as New York and San Francisco. A useful critical pairing would be Scott Herring's work on the Alabama photographer Michael Meads in Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism.26See Scott Herring, Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 99–124. As Herring demonstrates, Meads's photographs of nude and semi-nude young white men—often in the mise-en-scène of Confederate flags, guns, trophy deer, piney woods, and other objects that signal southerness to the viewer—short-circuit both homonormative assumptions about sexuality and gay identity and metronormative assumptions about sex and homophobia in the rural South.

Anecdotally, I've heard from a goodly number of southern gay white men who say that they like this kind of unsettling dynamic in S-Town. Apparently, to them, as to me, John B. McLemore's character feels at once enigmatic and familiar. He clearly doesn't fit mainstream constructions of either gay or southern identity; and yet, ironically, because of how he blends his intellectualism with a kind of down-home, country campiness, he also seems almost paradigmatically gay and southern. In a comment that he also relates to McLemore's sexuality, blogger Aaron Bady, who is originally from southern Appalachia, also notices this paradox: "John might seem like a one-of-a-kind, but hearing him instantly reminded me of any number of gifted hillbilly eccentrics I've known, red-state liberals whose local roots run deep and murky."27Aaron Bady, "Airbrushing Shittown," Hazlitt, May 1, 2017, https://hazlitt.net/longreads/airbrushing-shittown. The pejorative term "hillbilly" is specific to Appalachia and would not apply to the space of middle Alabama, let alone to McLemore. But, as someone who originates from Appalachia, Bady uses it interchangeably with "redneck" and other terms that generally refer to white southerners historically identified as "poor whites," which is to say, whites whose identities do not fit bourgeois normativities. He also uses these terms in ways that avoid perpetuating negative stereotypes, even as he remains outspoken against the racism, homophobia, and conservatism of so many white southerners.

Nevertheless, Reed's treatment of sexuality is, like his treatment of race and racism, immensely frustrating. In Chapter VI, he tells of how a gay man named Olin Long contacted him to talk about his relationship with McLemore, whom he met through a phone network for gay men in the time before apps like Grindr. They became intimate friends, but not lovers, and Reed dwells on their twelve-year relationship to bolster several assumptions about how hard it must be to be queer in the South, not just for McLemore in particular, but for anyone. (Shane Barnes runs with this notion in his review of the podcast on Vice; Michael A. Lindenberger offers a better take in the Dallas Morning News.28Shane Barnes, "'S-Town' and the Loneliness of Being Gay in the Rural South," Vice, April 13, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/aemwqg/s-town-and-the-loneliness-of-being-gay-in-the-rural-south; Michael A. Lindenberger, "S-Town Humanizes the Haunting Isolation of Gays in Rural America," Dallas Morning News, May 3, 2017, https://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/commentary/2017/05/03/john-bs-loneliness-tells-us-homosexual-life-rural-america.) Olin Long tells of his deep, moving appreciation of the film Brokeback Mountain, a story of repressed, rural gay love that Reed overlays onto Alabama. It turns out that Long has been celibate for nearly six years, and Reed automatically implies that, much like the Cowboy West of the movie, Long's celibacy is more the fault of the Red-State South than a choice he has made. "John and Olin," says Reed, "both kept their sexuality hidden for much of their lives. John talked to Olin and to me about how you had to be very careful about that where he lived."29Reed, "Chapter VI," 20:44. Later, Reed summarizes that "Living in Birmingham, Olin Long says at least he had places to go on a date, places where he could sit with another man in public and get a coffee or a drink. But John had nothing like that. There's not a single bar in all of Bibb County. And even if there was, it's hard to imagine two men feeling comfortable or safe going on a date there."30Reed, "Chapter VI," 21:47.

I certainly do not want to downplay the deep loneliness and fear that so many queer people experience, perhaps especially in rural locales. I also do not want to downplay the serious threats that LGBTQ+ people face in virtually every public space, certainly not limited to conservative southern spaces. In 1999, in Coosa County, Alabama, about seventy miles from Woodstock, Steve Butler and Charles Mullins murdered thirty-nine-year-old Billy Jack Gaither simply because he was gay, as they confessed.31See Allen Tullos, Alabama Getaway: The Political Imaginary and the Heart of Dixie (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011), 39–42. And in 2004, in Bay Minette, Alabama, down near Mobile, Christopher Gaines murdered eighteen-year-old Scotty Joe Weaver, in part because he was gay.32See Jen Christensen, "Scotty's Last Moments: The Murder of a Gay Teen—Allegedly at the Hands of His Best Friends—Has Rattled a Small Alabama Town," The Advocate, September 28, 2004. Both were high-profile cases that Long and McLemore almost certainly would have known. But gay life in the South is obviously more than just a matter of fear and violence, as we can easily see in the documentary Small Town Gay Bar (2006)—which discusses Weaver's murder alongside stories of queer resistance, love, and triumph—and in the work of writers and activists like Minnie Bruce Pratt, who hails from Centreville in Bibb County.33See Pratt's lecture "When I Say 'Steal,' Who Do You Think Of?" Southern Spaces, July 21, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/when-i-say-steal-who-do-you-think and her poem "No Place," Southern Spaces, July 27, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/no-place.

Or maybe if Reed had read John Howard's work on the history of gay male car culture in rural Mississippi he'd know that being gay doesn't always require brick-and-mortar buildings with rainbow flags in front.34See John Howard, Men Like That: A Queer Southern History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 78–125. As Howard's pathbreaking work reveals, LGBTQ+ people in Mississippi in the middle of the twentieth century, and gay men in particular, did not forge a sense of identity and community simply by meeting in bars or bookstores. Car culture was central: men met men in cars for sex, shared cars to travel back and forth between homes and towns and cities, and gathered in cars in unsurveilled rural spaces. Keeping in mind the different power dynamics attached to race, class, and gender presentation, LGBTQ+ southerners are able to come out and go out in towns and villages as well as cities. And sometimes, as we see in the case studies Howard discusses and in McLemore's own unusual friendship with Tyler Goodson, queer men don't need conventional (hetero) dating rituals to develop lasting relationships.

Moreover, doesn't McLemore tell Reed at the beginning of Chapter II that "Me and Roger Price had went up to the truck stop together to get a little dinner"?35Reed, "Chapter II," 0:28. They weren't on a date, but they were still two men sitting together, and they didn't encounter any homophobia. What does Reed think gay men do on dates that's different from what McLemore and Price did? More to the point, why doesn't Reed do more with McLemore's statement that "everyone around here thinks I'm a queer anyway"?36Reed, "Chapter I," 42:37. Reed uses this line as the title of Chapter VI, but he never really asks why McLemore would have to keep his sexuality "hidden" if his queerness is already, in a manner of speaking, public knowledge.

In any case, Reed backs away from that challenge and tells us that, because of McLemore's semi-rural Alabama situation, the only other potential partners he could find were an older man, "William," the married construction worker who tutored him in sex, and two other men whom he met on the phone line.37Reed, "Chapter VI," 16:58. Eventually, William faded away, and, according to Reed's account of what McLemore and Long told him, those other two men were too grotesque for words. One was "repulsive-looking, a chain smoker with tobacco-stained teeth," and the other had made a date at John's house only because he wanted a quick encounter.38Reed, "Chapter VI," 22:30. When McLemore didn't want to immediately jump into bed, according to Long, the man sat on the porch and "masturbated into whatever that flower bush was there. And then he left."39Reed, "Chapter VI," 23:42.

Alabama is certainly not the only place where you can find bad sex and awkward encounters. But Reed portrays Alabama as homophobic, intolerant, and virtually empty of that thirty-five-percent plurality of LGBTQ+ residents, making no real distinction between the surrounding countryside and Alabama's largest city (let alone larger cities like New Orleans, Miami, or Atlanta). Reed suggests that "Alabama" causes McLemore's loneliness far more than any of his idiosyncrasies or choices. Apparently, the problem had nothing to do with the fact that McLemore could be socially awkward, or that his strong personality might have scared some men away (remember that Reed waited a good while before he started replying to his initial calls and emails), but that he lived in a place where it's just too hard to meet the right guy. Ironically (or perhaps intentionally?), it never even seems to occur to Reed, the savvy creator of a digital podcast, that his queer subject might have moved on from antiquated telephone chatrooms to dating and hookup apps on his smartphone. It's as if the digital revolution missed Reed's version of Alabama altogether.

At least one reviewer has taken Reed to task for trying to force McLemore's sexuality to fit a normative frame of monogamy and romantic love, as if what he must have really wanted was an LTR that he could take on vacation to Fire Island.40Daniel Schroeder, "S-Town Was Great—Until It Forced a Messy Queer Experience Into a Tidy Straight Frame," Slate, April 11, 2017, http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2017/04/11/s_town_podcast_s_treatment_of_queer_experience_hobbled_by_straight_biases.html. But Reed's questionable portrayal produces another effect that brings me back to subjectivity. As he tells us about McLemore's failed relationships, Reed makes sure to remind us that his own sexuality is hardly so constrained. Once again, Reed uses his wife, Solange, to do so, telling us that it took him a while to reply to Long's email because it arrived during the time of Reed's wedding.41Reed, "Chapter VI," 7:37. Got it? Reed's sexuality is healthy and fully realized, while Long's and McLemore's erotic and romantic lives must go unfulfilled—because Alabama makes it too hard to come out and find a partner in the first place. To be clear, I'm not saying Reed is being homophobic. Rather, the podcast implies that if Long or McLemore had gotten out of Alabama, they could have found the same kind of happiness that Reed enjoys with Solange. In S-Town, they are tragic victims of location, while Reed is the liberal subject whose life in New York has (ironically) given him the freedom and autonomy to fully embrace his sexuality and find marital bliss.

Liberal Subjects

S-Town imagines a repressive and regressive "Alabama"—one that blurs into an equally backwards "South," regardless of whether it's rural, urban, or in between—in order to paint Brian Reed the narrator, and, by extension, all the podcast's listeners, as modern, mobile, and progressive. As Reed polices the narrative space of this queer and backwards Alabama, he never reveals something new that will change our perception of the state or our own circumstances. We never get past the cliché of a racism somehow predominately, if not exclusively, southern. We never find other ways to live and love that challenge the prescriptions of both hetero- and homonormativity. And we never remedy police corruption. Reed is no more interested in solving anything, including McLemore's suicide, than he is in reforming the actual institutions of the state of Alabama. Instead, just as D.A. Miller interprets in the Victorian novel, Reed uses a twisted Alabama to "repair normality" for listeners. Wherever we might be physically listening to the podcast, S-Town depicts Shittown, Alabama, in a way that makes us feel like we are all living in a better place.

How do we know our place is better? Because we don't need policing the way the people of Shittown do. Because in Shittown people are too openly racist, not like the "quieter" people of New York. Because in Shittown it's too hard to be gay. Because people in Shittown steal your property, dig up your gold, beat each other up in the woods, and so on. In Shittown people conduct dangerous experiments with mercury, even though the European milliners who wrote about the procedure back in the 1800s warned them not to. And, tragically, when the mercury poisoning combines with Shittown's other determining factors to finally drive you crazy, the people there don't even honor your last wishes by calling your friends when you die.

If I sound glib about McLemore's suicide, it's not because I actually feel that way, but because I believe the structure of the podcast is glib. The tone of the podcast honors the true genius of John B. McLemore. But the structure of S-Town tells us that the ultimate tragedy is that McLemore lived in Alabama and never got out. That is not to say that the podcast doesn't portray the citizens of Shittown as liberal subjects in their own right. But, like McLemore, they are always flawed subjects. When Tyler Goodson says in Chapter V that Reed must think he's a "bad person" for taking things off McLemore's land after his death, Reed condescendingly assures him: "No, man, I see you as a complicated, normal person. You know, I disagree with some of your decisions. But you also—you've had a very different life experience than I've had."42Reed, "Chapter V," 44:40, 44:50. A few minutes earlier in the podcast, Reta also worries that she would come across as a "bad person" because of her behavior in the property dispute (Reed, "Chapter V," 38:00). The implication here is that if Goodson had lived anywhere else—let's say New York—maybe he could have been just the same as Reed: well-traveled, successful, and "good." However, all the "bad" forces of Shittown have compromised Goodson by giving him a "very different life experience." Because of these forces, Reed suggests, Goodson will always remain "bad" and "different" from "normal" people, even if he could lift himself out of his poverty with the sudden windfall of McLemore's buried gold.

John B. McLemore, of course, is more extraordinary than Tyler Goodson. And, in terms of the narrative work of the podcast, this difference makes McLemore's fatal emplacement within Reed's southern imaginary an even greater tragedy. Reed expresses this idea in his depiction of McLemore as a crusader in Chapter II:

The shitty misfortunes John fixates on, they're not a bunch of disparate things. They're all the same thing. His Shittown is part of Bibb County, which is part of Alabama, which is part of the United States, which is part of Earth, which is experiencing climate change, which no one is doing anything about. It maddens John. The whole world is giving a collective shrug of its shoulders and saying fuck it.

What I admire about John is that in his own misanthropic way, he's crusading against one of the most powerful, insidious forces we face—resignation, the numb acceptance that we can't change things. He's trying to shake people out of their stupor, trying to convince them that it is possible to make their world a better place.43Reed, "Chapter II," 34:35.

From local corruption to planetary climate change, McLemore sensed all the social, political, economic, and natural forces that were acting upon—and against—humanity, and his tragedy was that he couldn't forget or disavow them. He could not find a way to survive because he could not blind or numb himself—even through pain—to the carceral restraints of our destructive global society. McLemore simply could not repair his own normality.

As the podcast implicitly tells us, however, we listeners still have the chance to forget and disavow. S-Town doesn't show us McLemore's almost panicked obsession with climate change so that we will also begin panicking about climate change. It doesn't tell his story so that we will run out and try to "change things." Rather, the podcast quarantines all that worry within John B. McLemore in order to repair our sense of our normality. Sure, we might worry about climate change a little—for, as D.A. Miller points out, the liberal subject's fantasy of being free from the world's determining forces also allows him to "conceive of himself as a resistance: a friction in the smooth functioning of the social order, a margin to which its far-reaching discourse does not reach."44Miller, The Novel and the Police, 207. Nevertheless, the point of the podcast is that we should be careful not to adopt McLemore's intensity and resist too much. As good liberals, we can fight for a new world of clean energy, interracial love, and queer comradeship, but the podcast suggests that if we fight too hard we might find ourselves buried next to John McLemore in Shittown. For if his brilliant mind couldn't change the forces that seek to discipline and destroy us at every level, how on earth could we?

Ultimately, the podcast is inviting us to identify with Reed, who is obviously freer and happier than all the residents of Shittown. In the logic of this work of aural literature, we must repair ourselves and our normality by imagining ourselves as a liberal subject like Reed the narrator, just as Victorian readers would have done. I don't mean that Reed is trying to shake us back into the "stupor" that McLemore was trying to shake us out of. But daily survival in a world on the brink of mass extinction really does require a lot of forgetting. In so many ways, our survival depends on our belief that we are persons with some power to resist. On its own, that belief will not help us stop climate change, but it's necessary all the same. And the fact that S-Town gives us these feelings of freedom and possibility explains its immense popularity. If a film version could accomplish the same thing—assuming the lawsuit against the podcast's makers allowed an adaptation to proceed—I imagine it would get even higher ratings, although I still cannot see how a film could do so without continuing to misrepresent Alabama and the South, and what it means to be queer in those spaces.

S-Town's literary predecessor, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, ends with a celebration of the restored and persistent pleasures of the southern gothic:

For me, Savannah's resistance to change was its saving grace. The city looked inward, sealed off from the noises and distractions of the world at large. It grew inward, too, and in such a way that its people flourished like hothouse plants tended by an indulgent gardener. The ordinary became the extraordinary. Eccentrics thrived. Every nuance and quirk of personality achieved greater brilliance in that lush enclosure than would have been possible anywhere else in the world.45John Berendt, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (New York: Random House, 1994), 388.

But in the story that Reed tells, nothing grows in the scorched earth of S-Town, where its key "eccentric" found he could no longer thrive. This inability to thrive is symbolized most clearly in the story of McLemore's hedge maze. In Chapter I, Reed dwells at length on the maze that McLemore and Goodson built on McLemore's land—a maze with moveable doors that allowed McLemore to create sixty-four different solutions as well as an insoluble "null set."46Reed, "Chapter I," 29:50. After McLemore's death, the maze fell into disrepair, and the hedges died. Although Reed does not talk about that decay, it is clear even within the podcast that the maze will never reach the "maturity" wished for in the final Chapter.47Brian Reed, "Chapter VII: You're Beginning To Figure It Out Now, Aren't You?" March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 24:27, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/7. The maze signifies McLemore's attempt to impose his own vision of order and wonder on the landscape. But after the podcast, we remain trapped in the maze of Reed's creation. When tourists go to Bibb County to look for the maze, they find they can only know it as they have encountered it in the podcast. As William Thornton writes for AL.com, many who visit the town of Woodstock do not find the Shittown they expect, for the maze is effectively gone and the citizens do not fit the impression that the podcast creates.48William Thornton, "The Seeds of S-Town: Woodstock Looks for Healing," AL.com, September 6, 2018, https://www.al.com/news/2018/09/the_seeds_of_s-town_woodstock.html. It is the podcast's depiction of Shittown that endures most of all.

If we could separate McLemore's voice from the narrative frame, what might we learn? Could he help us build new kinds of spatial narratives in addition to the temporal ones Rooney traces in her article? What might he teach us about being queer? Or even solving climate change? I am particularly interested in the possible links between his self-identification as a "semi-homosexual" and his becoming "unbanked."49Brian Reed, "Chapter III: Tedious and Brief," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 34:16, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/3. As he claimed to have mostly withdrawn from capitalist financial structures, how did he also imagine his sexuality as never fully fitting a coherent ideological category? How was he trying to occupy a subject position outside the control of capitalist networks and epistemologies that seek to make every individual fully knowable and accountable? What might be the advantages of other LGBTQ+ people following this lead—as southerners such as Minnie Bruce Pratt have been doing for years—fighting for sexual and gender liberation by revising and restructuring, or perhaps just rejecting, the systems of twenty-first-century global capitalism? Back in 1983, before the turn to the umbrella terms queer and LGBTQ+, historian John D'Emilio pointed out that "gay men and lesbians" were especially well positioned to build alternatives to exploitative capitalist regimes—to create models of sociality and community that "broaden the opportunities for living outside traditional heterosexual family units" and "provide a [stronger] material basis for personal autonomy."50John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," in Making Trouble: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and the University (New York: Routledge, 1992), 13. Up to his death in 2015, John B. McLemore was essentially calling for the same thing, but with even greater urgency.

Maybe if I went back and listened one more time, I'd find the answers to these questions buried in McLemore's monologues. But then I'd still be grappling with the narrative frame that arranges them into a meaningful structure. I'd be right back where I started, and still not a fan of the podcast. Maybe Brian Reed should just release McLemore's full recordings, monologues, and emails, however interminable and insufferable they may be. Listening to an unedited John B. McLemore might not be as entertaining or as pleasant, but it would still be profoundly interesting. Maybe that's what we need to "shake people out of their stupor" and show the rest of the nation that thirty-five percent of its queer population really do have something important to say.

About the Author

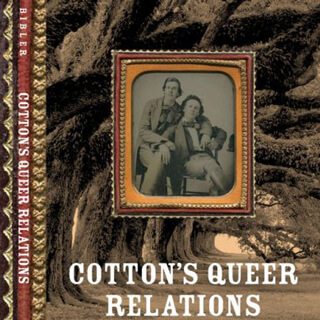

Michael P. Bibler is Robert Penn Warren Associate Professor of English at Louisiana State University. He is the author of Cotton's Queer Relations: Same-Sex Intimacy and the Literature of the Southern Plantation, 1936–1968 and co-editor of the collection of essays Just Below South: Intercultural Performance in the Caribbean and the US South. He is currently finishing a book manuscript about literalism and silliness in literature, music, performance, and film from the 1980s to the present, entitled "Literally, Queerly: The Pleasures of Silly Objects and Identities."

Cover Image Attribution:

Producer Brian Reed (right) interviews a clock collector in Alabama, 2016. Photograph by Andrea Morales. Courtesy of S-Town Podcast.Recommended Resources

Text

Dunn, Thomas R. Queerly Remembered: Rhetorics for Representing the GLBTQ Past. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2016.

Gray, Mary L., Colin R. Johnson and Brian J. Gilley, eds. Queering the Countryside: New Frontiers in Rural Queer Studies. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Herring, Scott. Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism. New York: New York University Press, 2010.

Howard, John. Men Like That: A Queer Southern History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Johnson, Colin R. Just Queer Folks: Gender and Sexuality in Rural America. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2013.

Kazyak, Emily A. "The Space and Place of Sexuality: How Rural Lesbians and Gays Narrate Identity." PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2010. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/873c/f926845227a897bcdf1bf4f6e1abb49f3246.pdf.

Rooney, Monique. "Queer Objects and Intermedial Timepieces: Reading S-town," Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 23, no. 1 (2018): 157–173. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0969725X.2018.1435392.

Web

Balaban, Samantha and Lulu Garcia-Navarro. "Bearing Musical Witness to John B. McLemore, the Late Protagonist of 'S-Town'." NPR. April 22, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/04/22/602169454/bearing-musical-witness-to-john-b-mclemore-the-late-protagonist-of-s-town.

Caison, Gina and David A. Davis. "S02 Episode 3: Gilded Souths & S-Towns." July 20, 2017. In About South. Produced by Gina Caison, Kelly Vines, and Adjoa Danso. Podcast. https://soundcloud.com/about-south/s02-episode-3-gilded-souths-and-s-towns.

Helmore, Edward. "'It's hell being famous': second violent death of Serial podcast character raises ethics questions," December 10, 2023. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/dec/10/s-town-serial-podcast-tyler-goodson-dead

Hasenbush, Amira, Andrew R. Flores, Angeliki Kastanis, Brad Sears, and Gary J. Gates. "The LGBT Divide: A Data Portrait of LGBT People in the Midwest, Mountain, and Southern States." The Williams Institute, 2014. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/lgbtdivide.

Movement Advancement Project. "Where We Call Home: LGBT People in Rural America." Movement Advancement Project, 2019. http://www.lgbtmap.org/file/lgbt-rural-report.pdf.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Amira Hasenbush, Andrew R. Flores, Angeliki Kastanis, Brad Sears, and Gary J. Gates, "The LGBT Divide: A Data Portrait of LGBT People in the Midwest, Mountain, and Southern States," The Williams Institute, December 2014, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/lgbtdivide. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Monique Rooney, "Queer Objects and Intermedial Timepieces: Reading S-town," Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 23, no. 1 (2018): 157. |

| 3. | Rooney, 159. |

| 4. | Rooney, 157, original emphasis. |

| 5. | Jessica Goudeau, "Was the Art of S-Town Worth the Pain? How a Decades-Old Literary Argument Adds Insight to the Debate over the Popular Nonfiction Podcast," The Atlantic, April 9, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/04/was-the-art-of-s-town-worth-the-pain/522366/; Aja Romano, "S-Town is a stunning podcast. It probably shouldn't have been made," Vox, April 1, 2017, https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/3/30/15084224/s-town-review-controversial-podcast-privacy. |

| 6. | EJ Dickson, "Judge Allows Lawsuit to Proceed Against 'S-Town' Podcast Makers," Rolling Stone, March 25, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/s-town-lawsuit-john-mclemore-estate-812965/. |

| 7. | Brian Reed, "Chapter II: Has Anybody Called You?" March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 44:22, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/2. |

| 8. | Brian Reed, "Chapter I: If You Keep Your Mouth Shut, You'll Be Surprised What You Can Learn," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 31:16, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/1. |

| 9. | Reed, "Chapter II," 22:48. |

| 10. | Reed, "Chapter II," 26:43, 25:28. |

| 11. | Katy Waldman, "The Gorgeous New True Crime Podcast S-Town is Like Serial but Satisfying," Slate, March 30, 2017, http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2017/03/30/s_town_the_new_true_crime_podcast_by_the_makers_of_serial_reviewed.html. |

| 12. | Rooney, 157. |

| 13. | D.A. Miller, The Novel and the Police (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988). |

| 14. | Miller, The Novel and the Police, 3. |

| 15. | Miller, The Novel and the Police, x. |

| 16. | Reed, "Chapter I," 32:50. |

| 17. | Literary critics David A. Davis and Gina Caison discuss these southern gothic tropes at length, including the comparison to Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily." Hear their excellent critique on the podcast "S02 Episode 3: Gilded Souths & S-Towns," July 20, 2017, in About South, produced by Gina Caison, Kelly Vines, and Adjoa Danso, podcast, MP3 audio, 38:27, https://soundcloud.com/about-south/s02-episode-3-gilded-souths-and-s-towns. |

| 18. | The story of southerners obsessively digging up land in the search for buried gold also echoes the plot of Caldwell's farcical God's Little Acre (1933). |

| 19. | Brian Reed, "Chapter V: Nobody'll Ever Change My Mind About It," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 16:10, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/5. |

| 20. | Wesley Jenkins, "The Empathy of 'S-Town' Doesn't Extend to Black People," BuzzFeed News, April 21, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/wesleyjenkins/the-empathy-of-s-town-doesnt-extend-to-black-people?utm_term=.fmJA3Xxxe#.jtpwXLBBz; Maaza Mengiste, "How 'S-Town' Fails Black Listeners," Rolling Stone, April 13, 2017, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/how-s-town-fails-black-listeners-w476524. |

| 21. | Reed, "Chapter II," 8:34. |

| 22. | Reed, "Chapter II," 7:58. |

| 23. | Reed, "Chapter I," 18:38. |

| 24. | Reed, "Chapter V," 49:09. |

| 25. | Reed, "Chapter VI: Since Everyone Around Here Thinks I'm a Queer Anyway," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 50:36, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/6. |

| 26. | See Scott Herring, Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 99–124. |

| 27. | Aaron Bady, "Airbrushing Shittown," Hazlitt, May 1, 2017, https://hazlitt.net/longreads/airbrushing-shittown. The pejorative term "hillbilly" is specific to Appalachia and would not apply to the space of middle Alabama, let alone to McLemore. But, as someone who originates from Appalachia, Bady uses it interchangeably with "redneck" and other terms that generally refer to white southerners historically identified as "poor whites," which is to say, whites whose identities do not fit bourgeois normativities. He also uses these terms in ways that avoid perpetuating negative stereotypes, even as he remains outspoken against the racism, homophobia, and conservatism of so many white southerners. |

| 28. | Shane Barnes, "'S-Town' and the Loneliness of Being Gay in the Rural South," Vice, April 13, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/aemwqg/s-town-and-the-loneliness-of-being-gay-in-the-rural-south; Michael A. Lindenberger, "S-Town Humanizes the Haunting Isolation of Gays in Rural America," Dallas Morning News, May 3, 2017, https://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/commentary/2017/05/03/john-bs-loneliness-tells-us-homosexual-life-rural-america. |

| 29. | Reed, "Chapter VI," 20:44. |

| 30. | Reed, "Chapter VI," 21:47. |

| 31. | See Allen Tullos, Alabama Getaway: The Political Imaginary and the Heart of Dixie (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011), 39–42. |

| 32. | See Jen Christensen, "Scotty's Last Moments: The Murder of a Gay Teen—Allegedly at the Hands of His Best Friends—Has Rattled a Small Alabama Town," The Advocate, September 28, 2004. |

| 33. | See Pratt's lecture "When I Say 'Steal,' Who Do You Think Of?" Southern Spaces, July 21, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/when-i-say-steal-who-do-you-think and her poem "No Place," Southern Spaces, July 27, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/no-place. |

| 34. | See John Howard, Men Like That: A Queer Southern History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 78–125. |

| 35. | Reed, "Chapter II," 0:28. |

| 36. | Reed, "Chapter I," 42:37. |

| 37. | Reed, "Chapter VI," 16:58. |

| 38. | Reed, "Chapter VI," 22:30. |

| 39. | Reed, "Chapter VI," 23:42. |

| 40. | Daniel Schroeder, "S-Town Was Great—Until It Forced a Messy Queer Experience Into a Tidy Straight Frame," Slate, April 11, 2017, http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2017/04/11/s_town_podcast_s_treatment_of_queer_experience_hobbled_by_straight_biases.html. |

| 41. | Reed, "Chapter VI," 7:37. |

| 42. | Reed, "Chapter V," 44:40, 44:50. A few minutes earlier in the podcast, Reta also worries that she would come across as a "bad person" because of her behavior in the property dispute (Reed, "Chapter V," 38:00). |

| 43. | Reed, "Chapter II," 34:35. |

| 44. | Miller, The Novel and the Police, 207. |

| 45. | John Berendt, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (New York: Random House, 1994), 388. |

| 46. | Reed, "Chapter I," 29:50. |

| 47. | Brian Reed, "Chapter VII: You're Beginning To Figure It Out Now, Aren't You?" March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 24:27, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/7. |

| 48. | William Thornton, "The Seeds of S-Town: Woodstock Looks for Healing," AL.com, September 6, 2018, https://www.al.com/news/2018/09/the_seeds_of_s-town_woodstock.html. |

| 49. | Brian Reed, "Chapter III: Tedious and Brief," March 28, 2017, in S-Town, produced by Brian Reed and Julie Snyder, podcast, MP3 audio, 34:16, https://stownpodcast.org/chapter/3. |

| 50. | John D'Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity," in Making Trouble: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and the University (New York: Routledge, 1992), 13. |