Overview

Launched in 1964, the War on Poverty quickly entered the coalfields of southern Appalachia, finding unexpected allies among working-class white women in a tradition of citizen caregiving who were seasoned by decades of activism and community service. In To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2019), Jessica Wilkerson tells how these women acted as leaders—shaping and sustaining programs, engaging in ideological debates, offering fresh visions of democratic participation, and facing personal political struggles. Their insistence that caregiving was valuable labor clashed with entrenched attitudes and rising criticisms of welfare. Their persistence brought them into coalitions fighting for poor people's and women's rights, healthcare, and unionization. The following essay is adapted from the epilogue of Wilkerson's book.

Blog Post

The activism of Appalachian women who took up the fight for justice in the 1960s and 1970s pulsed outward from a core ethic of care. Caregiving animated their understanding of politics and activism and infused their movements.1Berenice Fisher and Joan C. Tronto, "Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring" in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women's Lives, eds. Emily Abel and Margaret K. Nelson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 40. Historically, Appalachian women had tended to the broken bodies of miners and industrial workers, mourned the dead, raised children, and negotiated a subsistence economy. They did so not because women are inherently more nurturing than men but because culture, society, and law carved out these positions. Most caregivers do not become activists. The merging of an ethic of care with democratic struggle provided a powerful argument that caring is central to the fight for justice, fairness, rights, and democracy. Women drew upon their experiences in shaping movements for labor and welfare rights, environmental justice, access to healthcare, and women's rights.

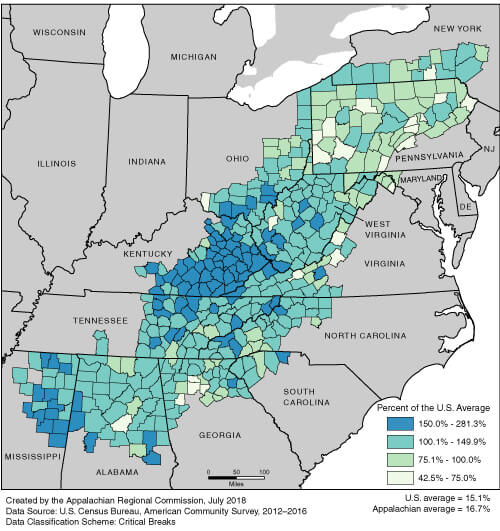

In the last thirty years, working-class caregivers have faced a US political economy ever more hostile to their needs and concerns and increasingly demanding of their time and energy. Although overall poverty has decreased since the 1960s, many locations in the Appalachian South, like rural and working-class communities across the nation, have experienced the rise of extreme economic inequality, and a growing divide between rural and metropolitan residents.2See Ronald D. Eller, Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008), 232–233. In the Appalachian coalfields, the last decades of the twentieth century ushered in the final and most precipitous decline of that industry. Although mine owners and operators had long exploited workers, mining was for many years the best paying work around. When those jobs disappeared, no other industry filled the gap and more people entered the low-wage service economy, surviving with little in the way of workplace benefits or economic security.

Relative Poverty Rates in Appalachia, 2012–2016 (County Rates as a Percentage of the US Average), July 2018. Map by the Appalachian Regional Commission. Courtesy of the Appalachian Regional Commission.

The loss of mining jobs and the transition to a global market and service economy paralleled the unraveling of the social safety net. In the 1990s, the bipartisan dismantling of Aid to Families with Dependent Children left poor families, and in particular women, on shaky ground and delivered a severe blow to decades of activism to guarantee welfare rights.3Deborah Thorne, Ann Tickamyer, and Mark Thorne, "Poverty and Income in Appalachia," Journal of Appalachian Studies 10, no. 3 (2004): 341–357. See also Debra A. Henderson and Ann R. Tickamyer, "Lost in Appalachia: The Unexpected Impact of Welfare Reform on Older Women in Rural Communities," Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 35, no. 3 (2008): 153–171. Health clinics, legal aid services, and local organizations—the legacies of 1960s activism—stood as the only buffers in a political economy increasingly hostile to poor and working people.

In the popular imagination, "Appalachia" functions as shorthand for a white working class—coded as male industrial workers. For months before and after the 2016 election, journalists reported on various Trump Countries, as they were dubbed—Appalachian communities supposedly serving as ground zero for understanding working-class support for a billionaire who claimed to care about the "forgotten people" of America. This signposting allowed for an evasion of any deep analysis of racism or growing economic disparity, generations in the making and never contained to one region.4Roger Cohen, "We Need 'Somebody Spectacular': Views from Trump Country," The New York Times, September 9, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/11/opinion/sunday/we-need-somebody-spectacular-views-from-trump-country.html; John Saward, "Welcome to Trump County, USA," Vanity Fair, February 24, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/02/donald-trump-supporters-west-virginia; Larissa MacFarquhar, "In the Heart of Trump Country," The New Yorker, October 10, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/10/in-the-heart-of-trump-country. For a full list and analysis of this coverage see Elizabeth Catte, "There is No Neutral There: Appalachia as Mythic 'Trump Country,'" October 16, 2016, https://elizabethcatte.com/2016/10/16/appalachia-as-trump-country/.

Such portraits rely on exhausted tropes that erase the voices and experiences of working-class women, a multi-racial and -ethnic group, from history while wiping from historical memory the progressive activism long central to Appalachia's history. Such a narrative ignores the experiences of the vast majority of the region's workers (many of them women) who are not employed in heavy industry, but in the work of caring: health care support, education, and social services.

Conceptions of "workers" that exclude and marginalize caregiving, or cast Appalachia as an isolated, out-of-step place, have little chance of generating the kind of diverse, hopeful coalitional work that emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Women activists in Appalachia and their allies—civil rights activists, lawyers, doctors, union organizers, feminists, and students—worked for what they believed was possible: the common good in their communities, region, and nation. Their most potent tool was the knowledge that they carried from a lifetime of tending to families, surviving tragedies, bearing witness to the disasters of unregulated capitalism, advocating for their communities, and taking stands for fairness and justice. Their stories are tools for the present, charting a path to a society that centers and values life-sustaining labor.

About the Author

Jessica Wilkerson is assistant professor of history and southern studies at the University of Mississippi.

Cover Image Attribution:

West Virginia Teachers' Strike, Charleston, West Virginia, March 2, 2018. Photograph by Emily Hilliard. Courtesy of the West Virginia Folklife Program at the West Virginia Humanities Council.Recommended Resources

Text

Carawan, Guy, and Candie Carawan, eds. Voices from the Mountains: Life and Struggle in the Appalachian South—The Words, the Faces, the Songs, the Memories of the People Who Live It. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.

Catte, Elizabeth. What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. Cleveland, OH: Belt Publishing, 2018.

Eller, Ronald D. Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008.

Engelhardt, Elizabeth S. D., ed. Beyond Hill and Hollow: Original Readings in Appalachian Women's Studies. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005.

Fraser, Nancy. "Contradictions of Capital and Care." New Left Review 100 (2016): 99–117.

Lewis, Helen M. Helen Matthews Lewis: Living Social Justice in Appalachia. Edited by Patricia D. Beaver and Judith Jennings. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012.

Maggard, Sally Ward. "'We're Fighting Millionaires!': The Clash of Gender and Class in Appalachian Women's Union Organizing." In No Middle Ground: Women and Radical Protest, edited by Kathleen M. Blee, 289–306. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Moore, Marat. Women in the Mines: Stories of Life and Work. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1996.

Rice, Connie Park, and Marie Tedesco, eds. Women of the Mountain South: Identity, Work, and Activism. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015.

Seitz, Virginia Rinaldo. Women, Development, and Communities for Empowerment in Appalachia. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Web

Achten, Ellee. "In Appalachia, Women Put Their Bodies on the Line for the Land." Rewire News, August 3, 2018. https://rewire.news/article/2018/08/03/in-appalachia-women-put-their-bodies-on-the-line-for-the-land/.

Appalachia: Family and Gender in the Coal Community Oral History Project. Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries (Lexington, Kentucky). Accessed March 8, 2019. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt773n20g49j.

"Appalshop." Appalshop, Inc. Accessed February 7, 2019. www.appalshop.org/.

Catte, Elizabeth."Finding the Future in Radical Rural America." Boston Review, January 26, 2019. http://bostonreview.net/politics/elizabeth-catte-finding-future-radical-rural-america.

Cheves, John, and Bill Estep. "Chapter 7: Bombs and Bullets in Clear Creek." Lexington Herald Leader, last modified August 29, 2018. https://www.kentucky.com/news/special-reports/fifty-years-of-night/article44430654.html.

Lewis, Anne. Evelyn Williams. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1995. https://www.appalshop.org/media/evelyn-williams/.

———. Fast Food Women. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1991. https://www.appalshop.org/store/appalshop-films/fast-food-women/.

———. Mud Creek Clinic. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1986. https://www.appalshop.org/store/appalshop-films/mud-creek-clinic/.

Phenix, Lucy Massie. You Got to Move: Stories of Change in the South. Harrington Park, NJ: Milestone Film & Video, April 17, 2015. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/36437/125290704.

Stine, Ali, and Cynthia Greenlee. "The Year in Appalachia: What Happened in 2018." Rewire News, December 19, 2018. https://rewire.news/article/2018/12/19/2018-appalachia/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Berenice Fisher and Joan C. Tronto, "Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring" in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women's Lives, eds. Emily Abel and Margaret K. Nelson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 40. |

|---|---|

| 2. | See Ronald D. Eller, Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008), 232–233. |

| 3. | Deborah Thorne, Ann Tickamyer, and Mark Thorne, "Poverty and Income in Appalachia," Journal of Appalachian Studies 10, no. 3 (2004): 341–357. See also Debra A. Henderson and Ann R. Tickamyer, "Lost in Appalachia: The Unexpected Impact of Welfare Reform on Older Women in Rural Communities," Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 35, no. 3 (2008): 153–171. |

| 4. | Roger Cohen, "We Need 'Somebody Spectacular': Views from Trump Country," The New York Times, September 9, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/11/opinion/sunday/we-need-somebody-spectacular-views-from-trump-country.html; John Saward, "Welcome to Trump County, USA," Vanity Fair, February 24, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/02/donald-trump-supporters-west-virginia; Larissa MacFarquhar, "In the Heart of Trump Country," The New Yorker, October 10, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/10/in-the-heart-of-trump-country. For a full list and analysis of this coverage see Elizabeth Catte, "There is No Neutral There: Appalachia as Mythic 'Trump Country,'" October 16, 2016, https://elizabethcatte.com/2016/10/16/appalachia-as-trump-country/. |