Overview

Drawing upon extensive observations published in the German-speaking states of northern Europe, Paul Warden addresses the collective medical geography of the Gulf South as revealed through nineteenth-century travel and settlement writing. Warden finds a strong correlation between the discourse of medical geography and German settlement patterns and raises questions about longstanding assumptions regarding the presence of slavery as the determining factor in German settlement.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy. Selected from a competitive group of submissions, these pieces offer new perspectives on the multiple meanings of health, space, and the public in the US and Global South. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Introduction

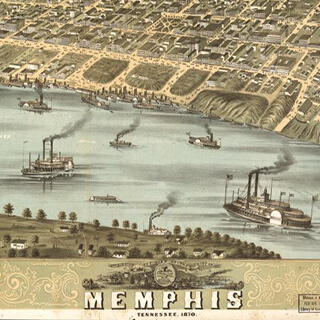

During the antebellum era, New Orleans became the second largest port of US immigration after New York City, leading hundreds of thousands of Germans to begin new lives at the mouth of the Mississippi rather than the Hudson. 1Carl Leon Bankston, ed., Encyclopedia of American Immigration, vol. 2 (Ipswich, MA: Salem Press, 2010), 476. New Orleans boasted one of the earliest and most vibrant German communities in North America, yet the German-born growth rate in Louisiana during these years pales in comparison to states such as New York and Pennsylvania, as well as that of other slave states such as Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland. In fact, between 1850–1860 it exceeds that of only Vermont, Maine, and South Carolina.2For the history of the settlement of Louisiana’s Cotes des Allemandes (the German coast) near New Orleans, see: Ellen C. Merrill, The Germans of Louisiana (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2005). Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth U.S. Census 1860a-04, 2–590; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Seventh U.S. Census 1850a-02, xxxvi. Could yellow fever and the imagined racial unsuitability of Germans to tropical climates help account for this phenomenon? A close examination of historical sources returns a resounding "Yes."

Mouth of the Mississippi, New Orleans, Louisiana, July 9, 2010. Photograph by Flickr user Adventures of KM&G-Morris. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

European Bodies, Climate, and the Geography of Yellow Fever

As a catalyst for German interest in America, the Louisiana Purchase unleashed a flood of speculation regarding whether US stewardship of the Purchase territory could lead to the realization of the biblical "land of milk and honey." According to observations reprinted by Johann Friedrich Nonne, editor of the Neue Allgemeine Weltbühne, in 1804, "the eyes of all Europe…now focused on Louisiana." The author of the piece downplayed concerns regarding the city's unhealthy reputation, which he attributed to the neglect of its former French caretakers, and expressed confidence that the territory's new masters would fare better in realizing New Orleans's potential.3Johann Friedrich Nonne, eds. Neue Allgemeine Weltbühne Auf Das Jahr 1804, (Erfurt, Germany: Johann Friedrich Nonne, 1804), 499; Thank you to Alexander Cors for encouraging a more suitable translation and for clarifying Nonne’s role in reprinting this piece. Over the next half-century Germans wrote extensively about the United States, particularly about the Louisiana Purchase and its suitability for settlement.

Heinrich Schmidt, ca. 1850s. Photograph by unknown creator. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

From 1815 onward, accounts of "travels in the New World became almost a mania among Germans."4Paul Weber, America in Imaginative German Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1926), 102–103. In 1836, for example, a single volume of the Jenaischen Allgemeinen Literatur-Zeitung reviewed twenty-one North American emigration guides.5“Neueste Colonisations-Schriften,” Ergänzungsblätter zur Jenaischen Jenaischen Allgemeinen Literatur-Zeitung 2, nos. 84–85 (1836): 281–295. Leading German newspapers began publishing weekly columns on culture and politics by Germans in America as well as observations on the relationship between climate and health.6Maria Wagner, ed., Was die Deutschen aus Amerika berichteten, 1828–1865 (Stuttgart, Germany: H. D. Heinz, 1985), x–xi. "In the most remote forest hut as well as in the middle-class dwelling," noted nineteenth-century German scholar Heinrich Julian Schmidt, "the only book that could be seen in the hands of a farmer or gentleman, was a book about America."7Julian Schmidt, Geschichte der deutschen Literatur von Leibniz bis auf unsere Zeit (1896; repr., Charleston, SC: Nabu Press, 2011), 271.

One of the most salient features of this writing was its demonstration of "Wissenschafts-popularisierung" (the popularization of science).8Andreas Daum, Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Jahrhundert: Bürgerliche Kultur, naturwissenschaftliche Bildung und die deutsche Öffentlichkeit (München, Germany: Oldenbourg, 2002). German writers from different walks of life consumed and disseminated knowledge from the burgeoning field of medical geography: the post-Enlightenment amalgamation of geography and the rediscovery of classical theories that insisted on the interrelationship between climate, environment, and disease.9Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997), 302; Mark Harrison, Contagion: How Commerce Has Spread Disease (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 49. One result was an attempt to demarcate the southernmost limits of acceptable German settlement based upon a racialized discourse of "climate" largely informed by the susceptibility of European bodies to yellow fever.

German-American historian La Vern Rippley acknowledged in 1976 that Germans often cited "climate" as a major deterrent to settlement in the southernmost United States. Rippley, however, apparently didn't consider the term within the parlance of the era.10La Vern J. Rippley, The German Americans (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1976), 44–45. More recent scholars have unpacked nuances of words like "climate" to reveal that nineteenth-century European and American understandings of health and disease were inextricable from their environment. When nineteenth-century Germans referred to their suitability to certain climates, they were often speaking about the perceived health of the land.11Conevery Bolton Valenčius, The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (New York: Basic Books, 2002); Linda Nash, Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006). Environmental historians, such as Conevery Bolton Valenčius and Linda Nash, have demonstrated how depictions of the health of the land were invaluable to nineteenth-century settlers in the burgeoning American West. Some German observers spoke favorably of the weather in Louisiana while simultaneously deriding the climate as ungesund (unhealthy).

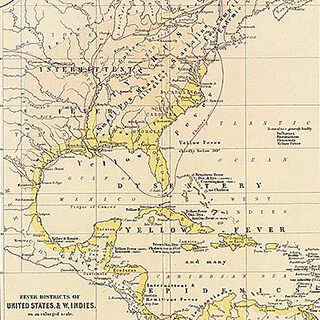

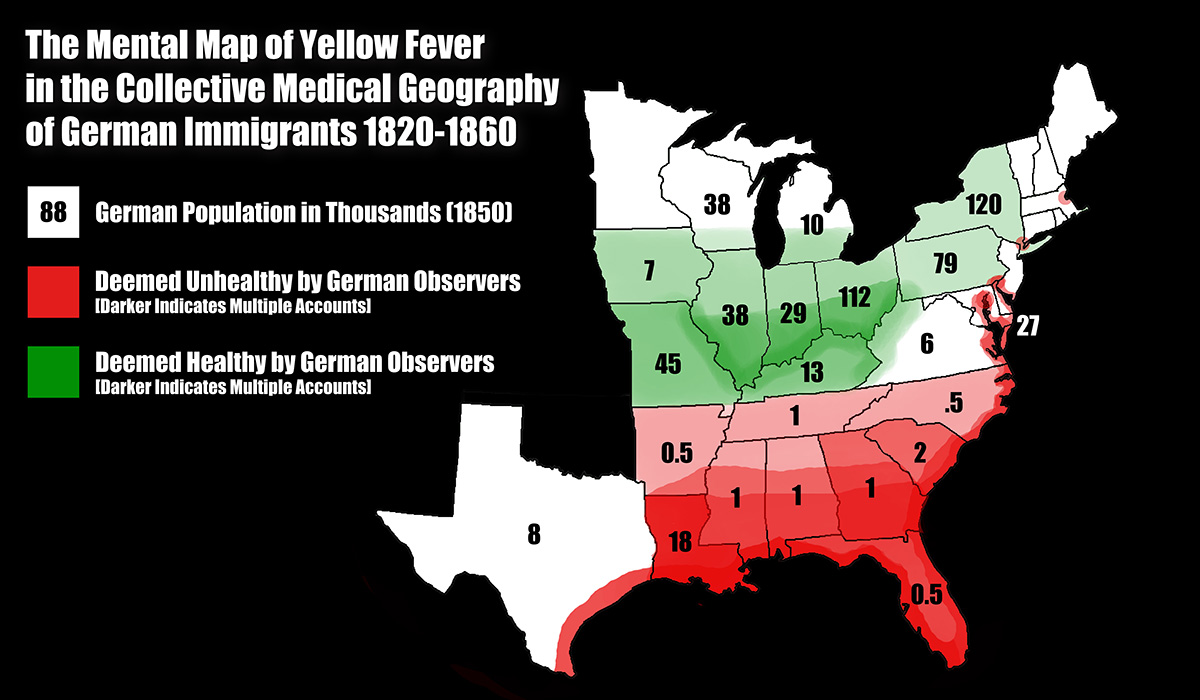

Drawing upon extensive observations published in the German-speaking states of northern Europe this article explores the collective medical geography of the Gulf South as produced through German travel and settlement writing. By collective medical geography, I refer to the gestalt of this literature within the minds of its readers. To get a sense of this perceived landscape, I have mapped the observations detailed in this work and laid them on top of each other, like transparencies on an old overhead projector (see figures below). Having mapped each author's medico-geographical observations, I juxtaposed them with immigration and settlement data from the seventh (1850) and eighth (1860) United States Censuses to demonstrate the effect of this discourse on German immigration and eventual settlement.12Both the census of 1850 and 1860 provide population statistics by nation of origin, providing the total number of German-born in each state. Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth U.S. Census 1860a-04, 2–590; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Seventh U.S. Census 1850a-02, xxxvi.

Top, The Mental Map of Yellow Fever, 1850. Bottom, The Mental Map of Yellow Fever, 1860. Maps provided by author.

The result suggests a strong correlation between the discourse of medical geography and German settlement patterns. It also raises questions about longstanding assumptions regarding slavery as the determining factor in German settlement, especially when one considers that slave states which received clean bills of health showed dramatic population increases. While some scholars have suggested that Germans avoided the US South almost exclusively due to their aversion to slavery, many German-American historians have cautioned against inscribing the beliefs of the outspoken Forty-Eighters on the entire German-American population, including the approximately 225,000 German-born citizens who lived in slave states on the eve of the Civil War.13For more on German-Americans and motivations for German-American settlement see: Merill, Germans of Louisiana, 9, 32–40; Walter D. Kamphoefner and Wolfgang Helbich, eds., Germans in the Civil War: The Letters They Wrote Home (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 2–3; Rippley, The German Americans, 51; Andrea Mehrländer, The Germans of Charleston, Richmond and New Orleans during the Civil War Period, 1850-1870 (Berlin, Germany: Degruyter, 2011) 14; Patricia Herminghouse, “The German Secrets of New Orleans,” German Studies Review 27 (February 2004): 1–12; Wagner, Was die Deutschen aus Amerika berichteten, xi–xii.

While anti-slavery sentiment was not uncommon among Germans, other reasons more likely led to their near complete avoidance of the Gulf South: availability of land, access to cities, industrialization, etc. Closer scrutiny reveals the importance, often above all other concerns, Germans placed on settling in a salubrious climate. When combined with German laments that New Orleans's insalubrity offset its economic and cultural potential, this collective medical geography—based almost exclusively on the presence of yellow fever—was a deterring factor for German settlement in the Gulf South.

Consider as well the seasonal patterns of German immigration through New Orleans. Once its insalubrity was established in this literature by the late 1840s, German authors turned to questions of New Orleans as an economically viable port of entry to the American interior. Founded in 1847, the Deutsche Gesellschaft von New Orleans (a German-American society, DGNO) embraced this role, as is evident in annual reports and communications that dissuaded Germans from settling in Louisiana due in large part to the presence of yellow fever. The DGNO advised immigrants to utilize the port as an economical and German-friendly point of entry, but to time their arrival so that it did not fall within the yellow fever season (late May through early October). By charting the port records of the DGNO between 1847 and 1860 (see figure above) a clear correlation between their recommendations to newcomers and the arrival of German immigrants becomes apparent.

Why did Germans single out yellow fever among prevalent diseases? After all, as then American diplomat and naturalist David Bailie Warden wrote in 1819, "the ravages of yellow fever are confined to the crowded streets of the most commercial towns, and its victims are less numerous than those of the bilious putrid fever, or typhus, which sometimes runs over [all of Europe]."14David Baillie Warden, A Statistical, Political, and Historical Account of the United States of America (Edinburgh, Scotland: Hurst, Robinson, and Company, 1819), 281. While Americans attempted to downplay yellow fever against concerns abroad, what was important to consider when qualifying German fascination with the disease was not how many yellow fever killed, but whom it killed and how they died.

Top, Aedes aegypti mosquito, August 20, 2012. Colored drawing by A.J.E. Terzi. Image uploaded by Flickr user Wellcome Images. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Bottom, Electron microscope image of the virus responsible for yellow fever, August 7, 2013. Photograph by Alain Grillet. Image uploaded by Flickr user Sanofi Pasteur. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

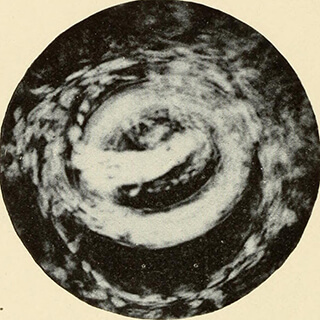

Unbeknownst at the time, yellow fever is transmitted to humans through a mosquito vector, the female Aedes aegypti. The mystery of the disease's transmission confounded contemporary medical observers leading to theories ranging from domestic origination of miasmas to the direct importation of contagious persons and/or inanimate fomites. There was broad consensus on two points: first, that the affliction targeted strangers to tropical climates, hence its moniker as a "strangers' disease," and, second, the erroneous assumption that individuals of African descent carried an inherent racial immunity.15Margaret Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 6–7. Jo Ann Carrigan, The Saffron Scourge: A History of Yellow Fever in Louisiana (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 1994), 10–11; Mariola Espinosa, “The Question of Racial Immunity to Yellow Fever in History and Historiography” Social Science History 38, nos. 3 and 4 (Fall/Winter 2014): 437–454. These two factors, whether real or imagined, carried tremendous weight for would-be German immigrants.

Beyond fears that they were more susceptible to yellow fever as strangers to the Gulf South, contemporaries suggested an underlying racial justification: the widespread belief that (white) Europeans and Americans could become acclimated over a period of years to regions otherwise hostile to their racial constitutions. Troubling to many observers, the process of acclimation suggested that the perceived immunity of slaves of West African descent confirmed a racialized climate theory often used to justify chattel slavery in the Trans-Atlantic South. That Europeans could acclimate to climates suitable for Africans raised concerns about whether the process led to racial mutability and/or degradation in whites.16David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 25–32. There is a lengthy historiography of racialized climate theory broadly conceived by Europeans in the nineteenth century. The following examples attest to American and European utilization of that theory within the American South: Mark Carey, “Inventing Caribbean Climates: How Science, Medicine and Tourism Changed Tropical Weather from Deadly to Healthy,” Osiris 26, no. 1 (2011): 129–130; A. Cash Koeniger, “Climate and Southern Distinctiveness” Journal of Southern History 54, no. 1 (February 1988): 21–44; and Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, 7. Not only would German bodies be extremely susceptible to this devastating affliction, becoming acclimated seemed to suggest that something inside them had changed.

The presence of tropical diseases, such as yellow fever, also shaped German conceptualizations of the Gulf South as a tropical place. Whereas the distinction between free and slave states has served to delineate between North and South in many US historical studies, it is evident from their descriptions and settlement patterns that nineteenth-century Germans viewed what political historians refer to as the lower South as being a part of a larger Gulf South: one that would include eastern Mexico and the Greater Caribbean. This is not to say that they did not appreciate the political distinctions between these places, but in terms of fitness for settlement words such as "tropical" and "West Indian heat," were often used to describe areas deemed ungesund.

This collective medical geography informed German imaginations, or cognitive mapping, of southern spaces such as the Gulf South's commercial center of New Orleans. Prior to photography and video—and before mass production of maps and illustrated books in the mid-nineteenth century—Europeans relied on the written or spoken word to inform their perceptions of places they had not visited. Settlement literature would influence the spatial imaginary. Writing that emphasized insalubrity and macabre scenes of epidemic yellow fever had a deleterious affect on German perceptions of New Orleans as a space.17Cognitive mapping has been utilized by a wide array of fields, but the most influential of these works are arguably those within environmental psychology and city planning. See: R.M. Kitchin, “Cognitive Maps: What are They and Why Study Them,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 14 (1994): 1–19; and Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1960).

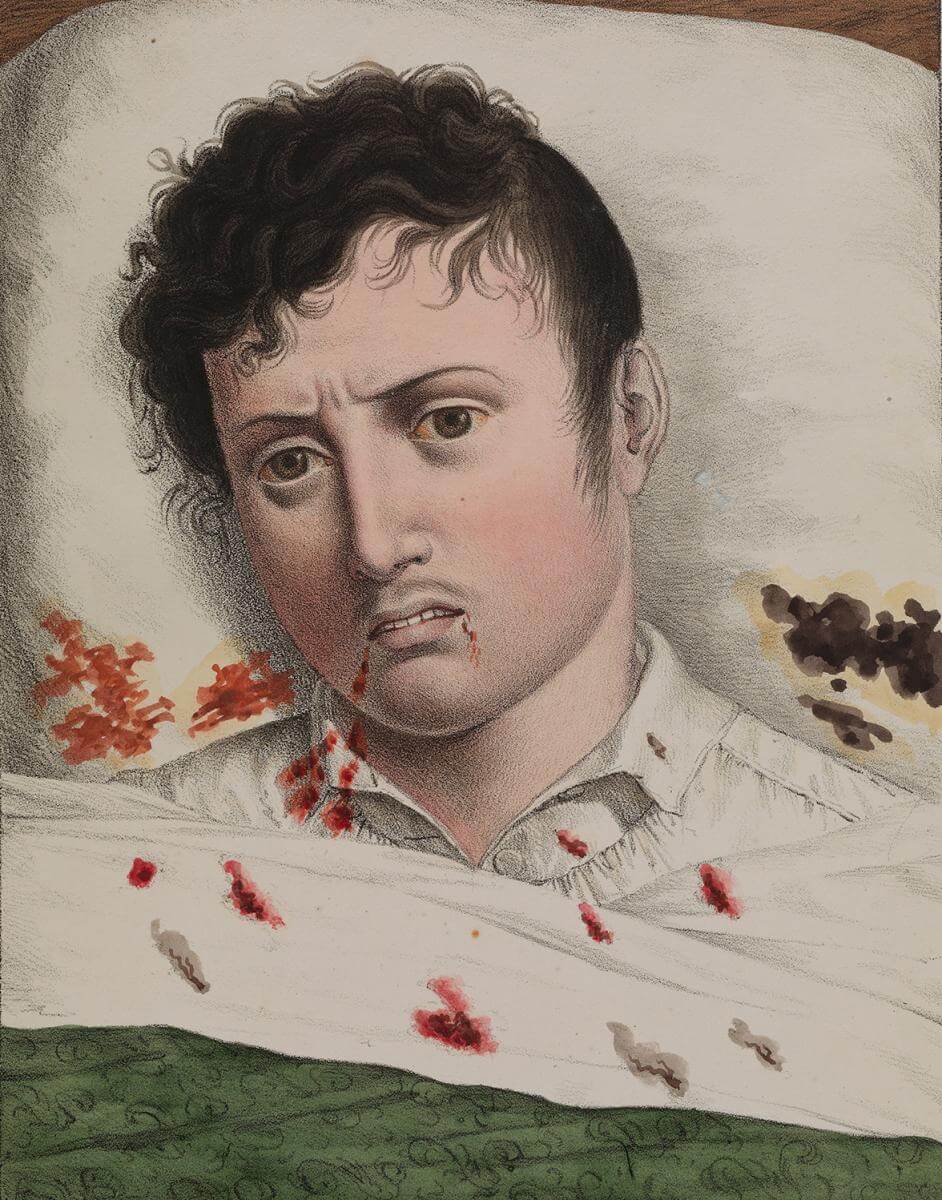

Development of yellow fever 1, 2, 3, 4. Illustration originally published in Etienne Pariset and André Mazet's Observations sur la fièvre jaune, faites à Cadix, en 1819. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

In addition to concerns of their unique susceptibility and fears of racial degradation in regions unbefitting their racial stock, the way in which yellow fever victims died embellished the disease's exotic and macabre reputation for would-be German settlers. The accumulation of the virus in the lymph nodes and the associated immune response leads to high fever and the onset of chills. As the liver is compromised, jaundice sets in, giving the victim's skin the yellowish hue that names the disease. Hepatic congestion brought on by liver failure and the eventual "systemic dysfunction of the clotting system" leads to hemorrhaging of the lining of the upper digestive system. Partially digested blood is forcefully expelled through the nose and mouth, producing a black vomit by which also characterizes the disease. Combined with descriptions of seizures and fevered delusions, lay accounts testify to the horror of this progression upon the afflicted and its effect on their caretakers.18Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, 5–6. It is no wonder that Germans placed as much emphasis on yellow fever as they did.

Travel Tales: The "Unhealthy Cities" of the South, 1820–1830

After the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), the optimism that Johann Friedrich Nonne expressed in 1804 regarding New Orleans's future salubrity was scarce among German authors. This coincided with the environmental trend in Enlightenment-era medicine that suggested nature exerted powerful forces upon the land and European bodies. Yellow fever was perceived as a product of tropical climates that could not easily be mitigated.19Ibid., 18–19; Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 302; Harrison, Contagion, 49. Germans who had traveled to tropical places during and after the Napoleonic Wars testified to the havoc these climates unleashed on German bodies. For many of these writers, the presence of endemic yellow fever was sufficient to designate a place as tropical and, therefore, ungesund.

Following his service as a Prussian artillery lieutenant in the Napoleonic Wars, Johan Valentin Hecke turned to "scientific pursuits and travel."20J. Valentin Hecke, Reise durch die Vereinigten Staaten von Nord-Amerika in den Jahren 1818 und 1819, vol. 1 (Berlin: H. Pb. Petri, 1820), 1. In his 1820, two-volume Tour of the United States of North America in the Years 1818 and 1819, yellow fever figured prominently. Little is known of Hecke's life beyond his military service, but a reviewer of his Tour in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung suggested that fellow Germans exercise caution in where they chose to settle.21“Vermischte Schriften,” Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1821): 785–792. They would do "better to be poor at home" than die abroad.22Ibid., 792.

A representation of the cholera epidemic depicting the spread of the disease in the form of poisonous air, or miasma, as Nonne and Hecke had observed. London, England, October 1, 1831. Lithograph by Robert Seymour. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in the public domain.

While, like Nonne before him, Hecke believed human agency—such as a lack of sanitation leading to pestilential miasma—could contribute to the unhealthiness of climate, the determining factor was "West Indian heat."23Hecke, Reise durch die Vereinigten Staaten, vol. 1, 76. This heat, Hecke and others insisted, exacerbated miasmatic conditions present in many port cities and led to increased frequency and virulence of tropical diseases: most notably, yellow fever.24Ibid., 166–67. Hecke's contribution lay in his detailed observations of major cities and their salubrity up and down the eastern seaboard and on the Gulf Coast.

Of all the diseases he encountered, Hecke devoted far more pages to yellow fever, dubbing it "the transatlantic plague," capable of striking "even among the hardened and seafarers accustomed to almost any climate." "Only a select few survive this terrible, nervous system-shattering disease," he wrote, and those who did would "never again reach their previous health."25Ibid., 167–183. As for the uneven distribution of yellow fever between North and South, Hecke estimated that the absence of persistent West-Indian heat explained why "in the northern states yellow fever is restricted to the seaports." While he assailed the "pestilential swamps" of the South as a haven for the disease, he noted that Delaware and New Jersey were dotted with marshes, yet "not one person has been carried away" by yellow fever.26Ibid., 166–67, 170

Bald cypress in Lake Drummond, Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia, August 2, 2006. Photograph by Rebecca Wynn, uploaded by Albert Herring. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

The further south Hecke traveled, the more he remarked on the prevalence of yellow fever. While he lauded the mountains of Virginia for their cooler and healthier climate, he was none too kind to the coastal areas. Hecke remarked that the "especially unhealthy city" of Norfolk and its surrounding coastline were dotted with pestilential fever-producing swamps. These swamps, along with high temperatures, incubated yellow and other malignant fevers that seemed to "occur almost every year."27Ibid., 161.

Of the Carolinas, Hecke was unabashedly critical. In Charleston, every summer the "burning West Indian heat" was "usually accompanied by the yellow fever."28Ibid., 166 Hecke wrote of a girl whose German-immigrant family operated a farm not far from Charleston when, without warning, yellow fever struck. Within a few days, the disease had orphaned her. Hungry and alone, she was found wandering the road.29Ibid., 167.

Yellow fever burial, Memphis, Tennessee, September 21, 1878. Illustration by unknown creator, published by Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. Courtesy of the Illustrations from Harper's Weekly Newspaper and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper collection, Digital Archive of Memphis Public Libraries.

"Despite all its glories," Hecke felt that New Orleans was "the unhealthiest place in the United States, and perhaps all of the Americas."30Ibid., 170–171. He noted "every year the yellow fever calls for its victims" in the Crescent City and that in the previous summer "one day after another, 100 [bodies] were lowered into the ground."31Ibid. He referenced the affliction's reputation as a strangers' disease, "so very dangerous not only for Europeans, but for northern Americans as well."32Ibid. Hecke's lament would be echoed in German settlement literature in the coming decades.

To emphasize the reach of the disease, Hecke wrote of a vessel anchored just outside of New Orleans during an outbreak. The ship carried "five young craftsmen who sought to take refuge [from yellow fever] in the northern states." After a short time removed from the port, each of the craftsmen fell ill. According to Hecke's informant, all five of them had fled only to perish before reaching their destination.33Ibid., 171. "No one [could] count on a long life in New Orleans, much less a comfortable one."34Ibid., 170–171.

Fellow Prussian artillery lieutenant Ignatz Hülswitt's portrayal of how yellow fever attacked and eventually killed its victims reads like a horror novel. Detailing the onset of this "fast-progressing and terrible disease," Hülswitt noted in the final stage, the victim could expect to endure "incessant vomiting and discharges of a black matter, which looks almost like tar" and "after a clear decline of all powers, strong jaundice, and maddening seizures, death usually comes on the seventh or eighth day." Hülswitt purportedly spoke from experience. Citing his own "irreplaceable loss," he claimed that during his time in Louisiana the disease had struck him down and robbed him of his "dear wife."35Ignatz Hülswitt, Tagebuch einer Reise nach den Vereinigten Staaten und der Nordwestküste von Amerika (Münster, Germany: Coppenrathschen Buch und Kunsthandlung, 1828), 306, 308. Hülswitt warned German readers that yellow fever resided "in the cities of Louisiana and causes much suffering," especially "among the newcomers."36Hülswitt, Tagebuch einer Reise nach den Vereinigten Staaten, 305–306. Despite praising the state as "indisputably one of the most beautiful in America," like Hecke, Hülswitt lamented his racial unsuitability for Louisiana.37Ibid., 304.

In a review of Hülswitt's work in the Neue Allgemeine Geographische und Statistische Ephemeriden, prospective immigrants to Louisiana were cautioned that, despite attaining a "comfortably furnished home on 160 acres of land," yellow fever had taken Hülswitt's wife and ravaged his constitution to the extent that he spent a year rehabilitating "without being able to recover from the effects of the fever."38Neue Allgemeine Geographische und Statistische Ephemeriden, (Weimar, Germany: Geographischen Institut und des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1830) 215. The affordability of land and the lure of prosperity came with dangerous consequences.

Unbeknownst to readers, Hülswitt may have fabricated the incident. Scholars have confirmed that he plagiarized much of his 1828 Diary of a Trip to the United States and the Northwest Coast of America from Englishman John R. Jewitt's Journal Kept at Nootka Sound: an account of Jewitt's abduction, enslavement, and eventual assimilation into the Nuu-chah-nulth tribe. While the portion of his book that dealt with his bout with yellow fever in Louisiana has not yet been attributed to any other author, there is no proof that Hülswitt traveled to America.39Peter Littke, “Ignatz Hülswitt, the German ‘John R. Jewitt’ at Nootka Sound?” The Initiative for Russian American History, April 2002, www.irah.eu. It's possible that Hülswitt's narrative of his family's bout with yellow fever was an attempt to exoticize an already sensational tale.

In 1835, encouraged by the swell of interest in travel narratives, Duke Friedrich Paul Wilhelm, a naturalist, explorer, and nephew of the first king of Württemberg, published his First Travels in North America, 1822–1824.40Friedrich Paul Wilhelm, Travels in North America 1822-1824, ed. Robert Nitske and Savoie Lottinville (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), xiii. Having spurned the military life in pursuit of botany and other natural studies, "Duke Paul" set out to further the work begun by his idols, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. As a self-styled expert of natural science, he believed himself an ideal candidate to report on the climate and ecology of Louisiana and its environs.41Ibid., xv, xiii–xx.

Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg. Image by unknown creator. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

Landing in New Orleans, Wilhelm reports he was briefed on the recent yellow fever epidemic and felt blessed that a delay had kept him from arriving at its peak. "Many German countrymen who had not left," he reported, "had fallen victim to its plague."42Ibid., 34. The following year he escaped another yellow fever epidemic as it swept through. Returning to the city from yet another trip to the "interior of North America," Wilhelm was "saddened by the news of the death of a highly valued friend." He consequently declared "all strangers [should] shun New Orleans from June to November."43Ibid., 21, 34.

Like his counterparts, Duke Paul found much to appreciate in New Orleans. Enthralled by the city's commercial potential and the steamships that traveled the Mississippi, he wrote that "trade and population would increase enormously if the climate and unhealthful situation did not disturb both."44Ibid., 34. He had little faith in New Orleans's measures to combat yellow fever, noting that a "quarantine station intended to protect the city from contagious diseases" was too far up river to prove effective. Ships could disembark early and circumvent quarantine, enabling those exposed to the disease to "go unhindered in the city."45Ibid., 31.

That Wilhelm traveled through Louisiana at this time appears to be corroborated by other accounts. He purportedly crossed paths with a young German named Max who had escaped a yellow fever epidemic that had decimated St. Francisville, Louisiana. Max's account comes from letters edited and published by his father in Ulm alongside those of his sister and uncle in Excerpts from Letters from North America (1833).46Auszüge aus Briefen aus Nord-Amerika, geschrieben von zweien aus Ulm an der Donau gebürtigen, num in Staate Louisiana ansässigen Geschwistern (Ulm, Germany: E. Nübling Book Printers, 1833), 32–35, 51. Not to chance misinterpretation, Max's father emphasized his purpose for publishing his children's letters in an ominous foreword. He asked that "the youth and newly married couples who felt the impulse to emigrate to North America" heed this cautionary tale left behind, "especially the descriptions of the state of Louisiana and New Orleans."47Ibid., foreword.

In writing of a steamboat trip from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, Max noted the well-developed land and beautiful plantations.48Ibid., 22–23. He remarked on the affordability of life in Louisiana, adding that he and his uncle were able to rent their storefront, an African slave, and a wagon for only fifty-three Spanish talers per year.49Ibid., 28. Max expressed fear, however, of the area's becoming "unhealthy" by summer due to the annual flooding of the river and the formation of swamps as it receded.50Ibid., 25. That Max's unabashed participation in slavery and praise of Louisiana's economic accessibility is counterbalanced with fears of impending yellow fever presents a familiar theme.

Death of Aurelio Caballero due to yellow fever in Veracruz, 1892. Etching on zinc by José Guadalupe Posada. Courtesy of the Drawings and Prints department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In a letter dated November 18, 1827, Max described an outbreak of yellow fever presumably brought by steamboat in September.51Ibid., 51. The disease initially spread among the unacclimated, "new arrivals and the older residents." Six weeks into the epidemic, Max reported that he had fallen victim. Suffering from inflamed eyes and a blackened tongue, he recalled feeling "an unusual accumulation" in his mouth, at which point he "pulled out a large piece of spalted black blood." Soon the blood poured out of his mouth and nose as doctors tried desperately to take his pulse. Max reported that he had "vomited about two sinks full of blood" that day and was failing fast. Miraculously, he made a full recovery, the lone survivor among those infected.52Ibid., 52.

Max's expressed concern for fellow Germans seeking to land in New Orleans during the summer months is also telling. In June 1828, he lamented that during his time in New Orleans, a ship "brought about 120 Germans of diverse ages" who were ill prepared to travel to the interior. Without sufficient money, they were forced to beg while the "heat during and after the flooding of the river…will soon bring about the Yellow Fever." Disheartened, Max knew that his "countrymen, who have come here so hearty and strong from healthy Germany, will fall without a fight as its first victims."53Ibid., 62–63.

When Max's sister Thekla came to America, he suggested that they meet in New York in the late fall and travel to New Orleans by steamship only after the fever season had ended. Despite their careful planning, Max reported the fever had lingered late that summer and was terrorizing New Orleans well into November. He noted that the twenty or so Germans on board decided to immediately travel north "for the sake of the preservation of their health." According to Thekla's account, she and Max retired to their quarters where they held each other and cried—praying the fever would leave them unscathed. Upon their arrival, Max and Thekla heeded the advice of "some experienced Germans" to remain onboard rather than risk entering the city.54Ibid., 148. While they survived the ordeal, Max and Thekla's letters emphasized the danger posed to Germans by yellow fever in the Gulf South. The lesson Max's father intended comes through loud and clear—wanderlust had perilous consequences.

The authors of this first period of travel and settlement literature placed more emphasis on personal observation buttressed by hearsay than scientific analysis. Even self-styled naturalists, such as "Duke Paul" and Johan Valentin Hecke, offered little data, aside from notions of yellow fever's limited range from the sea. During the mid-nineteenth century, the "Wissenschafts-popularisierung" (the popularization of science) became more apparent. Just prior to the height of German immigration to the United States, writers would provide scientific evidence that explain earlier observations and explore the presumed relationship between southern climates and German bodies that made them more susceptible to yellow fever.

"Too Far South": Yellow Fever, Race, and German Fears, 1830–1845

Beginning in the 1830s, there was a perceivable shift from travel and adventure narratives towards settlement guides and treatises on medical geography. Of particular interest were the increasingly prevalent theories of acclimation, as well as the utilization of latitudinal coordinates to pinpoint unhealthy areas for German immigration. The shift in emphasis from dissuading settlement in New Orleans to debating its merits merely as a viable port of entry for Germans settling elsewhere suggests that the unhealthy nature of the climate was increasingly taken for granted.

Cover of Gottfried Duden's Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980).

The most well known German travel and emigration author of the nineteenth century, Gottfried Duden, extolled the virtues of the slave state of Missouri for prospective German immigrants in his Report on a Trip to the Western States of North America (1829).55Gottfried Duden, Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas (Elberfeld, Germany: S. Lucas, 1829). Reprinted three times, his Report became so popular that German authorities feared it might inspire a mass exodus to Missouri.56Robyn Burnett and Ken Luebbering, German Settlement in Missouri: New Land, Old Ways (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996), 10. Historians have long noted the significance of Duden's Missouri boosterism,57Robert Frizell, Independent Immigrants: A Settlement of Hanoverian Germans in Western Missouri (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 29; Conevery Bolton Valenčius, Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 37; Richard O’Connor, The German-Americans: An Informal History (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1968), 68–70; Rippley, The German-Americans, 44. but his remarks on the southern limits of German settlement and yellow fever's role in establishing them have been largely ignored. Duden advised his readers to stay north of "settlements at the mouth of the Arkansas [River]," some 325 miles north of New Orleans, as they were "perhaps too far south." The main reason for his admonitions was yellow fever, which he claimed struck the Crescent City "almost every summer."58Duden, Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas, 165–166, 328.

Duden argued that the dangers of yellow fever and other tropical diseases kept Germans from areas in which slavery was most depraved. In the middle states, like Missouri, he contended, slavery was a relatively benign institution, comparing favorably to domestic servitude in Europe, and often in the best interests of the enslaved. The greatest obstacle slaves faced to freedom, Duden believed, was their racial inferiority. He asserted that no amount of education or betterment could undo thousands of years of being exposed to debilitative, and inferior, climates.59Ibid., 142–143.

Duden maintained that Germans could not saunter into a tropical climate without prolonged seasoning.60Ibid., 328. He cautioned readers not to be enticed by the availability of inexpensive tracts of land where their health would be imperiled. Germans, he argued, should settle in Missouri, preferably near St. Louis.61Ibid., 328, 330. While he recommended traveling there from New York or some other northeastern port, he conceded that traveling to Missouri by way of New Orleans was feasible, so long as one embarked from Germany no later than "December or January so that they arrive when there is no danger from yellow fever."62Ibid., 332.

Observing that many Europeans survived in cities such as New Orleans seemingly unaffected by diseases such as yellow fever, Duden based his concepts of acclimation and seasoning on a version of racialized climate theory in which racial traits were somewhat mutable.63Ibid., ix–xiv, 110. Seasoning or acclimation attempted to scientifically explain yellow fever's reputation as a strangers' disease. When his methods of acclimation failed and the promise of his Missouri boosterism went unrealized, Duden came to be known in many settlements of the mid- to upper Mississippi River Valley as "Duden der Lügenhund" (Duden the Lying Dog).64T.S. Baker, “America as the Political Utopia of Young Germany,” Americana Germanica 1 (1897): 78.

Letter from Gustave P. Koerner to Abraham Lincoln, Springfield, Illinois, October 8, 1861. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Abraham Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division, memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mal&fileName=mal1/123/1235900/malpage.db&recNum=0.

A young Gustav Koerner took exception to Duden's proclamations. As an abolitionist fresh off the boat from Frankfurt in 1833, Koerner would become Illinois's most renowned German son as well as a political confidant and close friend of Abraham Lincoln.65Jack Le Chien, “We Must Make Them Understand Lincoln is Our Man,” ed. Molly McKenzie (Bellville, IL: Koerner House Restoration Committee, 2011), 14. In his Illumination of Duden's Report on the Western States of North America, from America (1834), Koerner encouraged the German public to question Duden's observations regarding the health of St. Louis. In particular, he questioned how a city in constant contact with New Orleans, a locality known to harbor "diseases of all kinds, but especially yellow fever," could possibly be considered healthy. Koerner cited longtime residents of St. Louis who confirmed that the health of the city worsened since the advent of regular steamboat traffic to and from New Orleans.66Gustav Koerner, Beleuchtung des Duden’schen Berichtes über die westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas, von Amerika aus (Frankfurt, Germany: Karl Körner, 1834), 28. It is important to acknowledge Koerner's role as a booster in Illinois. Both Duden and Koerner were selling the virtues of a place to prospective immigrants. Disagreements aside, they agreed on two principles: the universal condemnation of New Orleans as being host to endemic yellow fever (ungesund) and that Germans who settled too far south did so at their peril.

German-born academic and journalist, Francis Grund, echoed Duden's theory of acclimation in a piece for the Ausberger Allgemeine Zeitung, entitled "Die Colonisation von Liberia." Published in 1840, the article was sectionally biased. As the anti-slavery Grund lived in the North, his article about the colony of Liberia begun by the American Colonization Society offered few kind words for the South's peculiar institution. In his discussion of African Americans' perceptions of Liberia as a "morgue for the blacks," he made a corollary observation of yellow fever and the southern United States. Writing that blacks and "acclimated" residents of the South need not fear "this scourge of Mankind," Grund voiced another reminder that yellow fever was a strangers' disease and that those foreign to the South risked infection and their lives when this "yearly" affliction struck.67Duden, Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas, ix–xiv, 110.

The yellow fever scourge in Florida, September 8, 1888. Illustration by unknown creator, published by Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. Courtesy of the General: Reference collection, Florida Memory website, The State Archives of Florida.

So influential were Grund's opinions of the US that one scholar referred to him as "The Jacksonian Tocqueville."68Holman Hamilton and James L. Crouthamel, “A Man for Both Parties: Francis J. Grund as a Political Chameleon,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 97 (1973): 465–484. Alongside observations of culture and politics in his 1835 Die Amerikaner (The Americans), Grund offered a chastising observation of the climate in the Carolina Low Country. He warned that the region was "visited each year by the yellow fever" and insisted that even the interior or rural portions of the Carolinas and Georgia were not safe.69Francis Grund, Die Amerikaner: in ihren moralischen, politischen, und gesellschaftlichen Verhältnissen (Stuttgart, Germany: J.G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, 1837), 363.

German observers often suggested what areas were "healthy" for German bodies. Friedrich Schmidt's Account of the Politics and Moral Condition of the United States of North America in the Year 1821 was published shortly after Hecke's first volume. Schmidt was quick to address the mania surrounding German emigration and in his use of medical geography and latitudinal coordinates, he was a pioneer. He offered five observations as to "which areas of North America are especially unhealthy and which states might be beneficial for Europeans."70Schmidt, Versuch über den politischen Zustand der Vereinigten Staaten von Nord Amerika im Jahre 1821, 82.

Schmidt wrote that American climates were subject to rapid change and posed a potential threat, but that all areas south of "thirty-six degrees north latitude" were tropical and would "devastate European constitutions." He warned of uncultivated soils and "the reigning diseases" of the "southern and western states" that caused "exhaustion and death among Europeans and Americans." And significantly, he claimed that the "healthiest and most beneficial areas in North America for Europeans, are the states of Pennsylvania, New York, and around the southern parts of Ohio and Indiana."71Ibid., 82. As the maps accompanying this essay show, these states displayed high rates of settlement among German-born immigrants.

Ludwig Gottfried Blanc. Image by unknown creator. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

Written fifteen years later by renowned preacher, philologist, and professor of Romantic Languages at the University of Halle-Wittenberg, Ludwig Gottfried Blanc's Handbook of Essential Knowledge of the Nature and History of the Earth and its Inhabitants (1837) was a comprehensive study intended for a broader audience of fellow Germans.72Ludwig G. Blanc, Handbuch des Wissenswürdigsten aus der Natur und Geschichte der Erde und ihrer Bewohner Vol. 3 (Halle, Germany: C.H. Schwetschke und Sohn, 1837). In "The United States of North America" under the subheading of "Climate," Blanc summarized the health of the US landscape. "[T]he East Coast," he wrote, "particularly from 40° South [latitude] is, for the most part, unhealthy, and most so in the southern states." Blanc singled out the "terrible yellow fever" as the "main plague of these areas," adding that in the hotter southern states even the interior was susceptible to its devastation.73Ibid., 471.

Blanc remarked favorably on the salubrity of New England, but claimed that the "interior states, between 36° and 42° are, by far, the most healthy."74Ibid., 454. This area included Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, and the southern portions of Michigan and Wisconsin where, by 1860, over half of the German-born US population resided. If the western portions of Pennsylvania and New York were included as "interior states," the proportion would rise to roughly three-quarters.75Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census 1860a-15 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1864), 621. For Blanc, the yellow fever zone extended down the eastern seaboard from New York City, with an increase in virulence and general unhealthiness the further south one traveled. He was especially critical of the coastal areas from Maryland southward, reserving particular scorn for Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.76Blanc, Handbuch des Wissenswürdigsten, 479–492.

While differing in content and methods from earlier travel and adventure narratives, the settlement guides of 1830–1845 came to very similar conclusions, emphasizing the destructive power of yellow fever and its relation to southern geography. Rather than take a chance on acclimation, it was better to avoid the area altogether. On the eve of the greatest period of German immigration to the United States, prospective immigrants were inundated with warnings about the lower Gulf South, and particularly New Orleans. With the question of where to settle, one question remained: was New Orleans still a viable port of entry for Germans heading for California, Texas, and the upper Midwest?

Just Passing Through: New Orleans, 1845–1860

Death as a sailor bringing yellow fever to New York. Illustration by unknown creator, published by Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. Courtesy of the Civil War Profiles website.

The emphasis of German writings of the late 1840s and 1850s shifted to discussing the viability of New Orleans as a port of entry for immigrants planning on settling outside the Gulf South. Despite the threat of yellow fever, writers acknowledged New Orleans as an economical port for those heading to the US interior. Even here, there were stipulations, the most damaging of which dealt with the time of year to arrive to avoid yellow fever.

George M. von Ross, an American of German descent and a well-known booster of German immigration to central Texas, wrote several guides. While affirming New Orleans as an economical alternative to ports in the Northeast, Ross, in his 1851 The Emigrants' Handbook, warned that those who sought to immigrate through New Orleans "must avoid landing during the period of July to November" or they would "risk finding [the city] haunted by yellow fever upon their arrival."77Ross, Die Auswanderers Handbuch, 404. Books by Gabriel Auguste van der Straten-Ponthoz and Traugott Braume shared Ross's concerns and warnings.78Gabriel Auguste van der Straten-Ponthoz, Forschungen uber die Lage der Auswanderer in den Vereinigten Staaten von Nord Amerika (Augsburg, Germany: K. Kollman Publisher, 1846), 79–80. Braume, in particular, suggested that those headed for the interior of Texas were better off landing in Galveston which, despite being host to yellow fever on occasion, he deemed a safer alternative.79Traugott Braume, Hand- und Reisebuch für Auswanderer und Reisende nach Nord, Mittel, und Süd-Amerika (Bamberg, Germany: Buchner Publishing, 1853), 612–613.

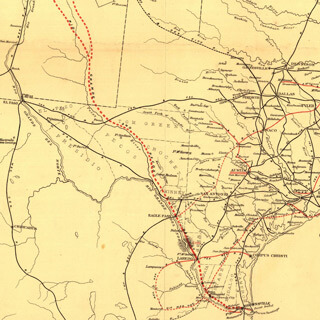

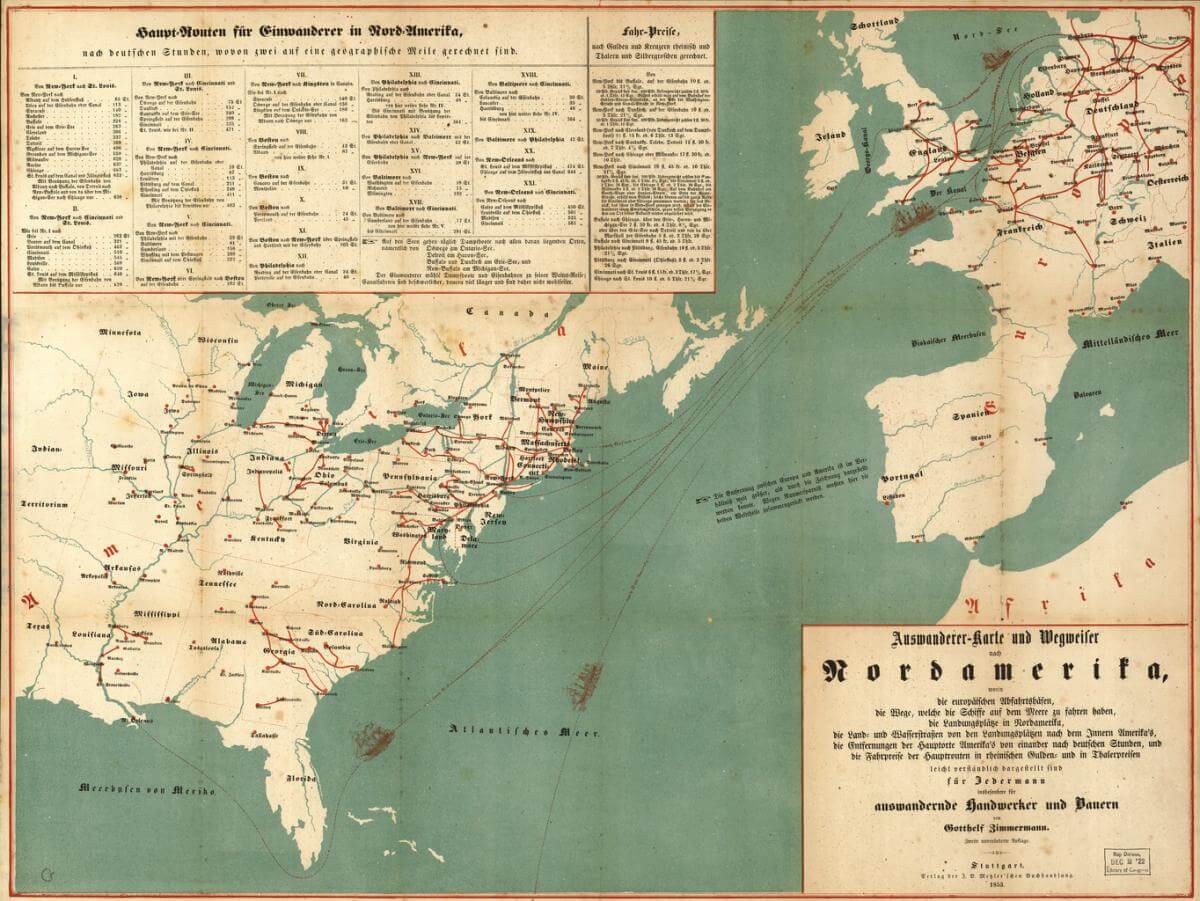

Auswanderer-karte und wegweiser nach Nordamerika, Emigration map and guide to North America, Stuttgart, Germany, 1853. Map by Gotthelf Zimmermann, published by J.B. Metzler'schen Buchhandlung. Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, loc.gov/resource/g3701e.ct000244/.

Established in 1847, the Deutsche Gesellschaft von New Orleans (DGNO) sought to increase German immigration through the Crescent City. It provided inexpensive or free services to those heading to the interior, and tried to protect German immigrants from fraudulent travel "brokers," false baggage handlers, and yellow fever. The organization did not actively recommend New Orleans as a final destination, but aspired to make the city the primary port of entry for German-speakers.80Historic New Orleans Collection (HNOC), Deutsches Haus Collection 1847–1983 EL 1. 1984 Item 1—Die Deutsche Gesellschaft von New Orleans, Louisiana. 1848–1888.

The DGNO closed its first annual report with an unattributed quotation that eventually found its way into the Central Association of German Emigration and Colonization's 1852 circular "To all who want to emigrate!" It advised prospective German emigrants to:

...remain in the land that nourishes you fairly because you come to a country where climate, language, customs and traditions are quite different from your own. There have been many cases in which immigrants have befallen the bitterest price of woes, regretted the reckless step taken, and who, though often in vain, must beg for the means to return to the homeland.

The circular noted that those who sought "to improve their situation" were "only too often met by a terrible awakening." For "malignant fever is almost inevitable everywhere and is often fatal if the right care cannot be found."81Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz. Inventory: 441, No. 24, 215. www.t-stoffel.de/QUELL/Quellen/An%20alle%20die%20auswandern%20wollen%202.htm.

While originally conceived as an organization to protect German immigrants from false agents and travel brokers, the DGNO realized quickly that disease posed an even greater threat and understood their "special duty to advise immigrants to schedule their arrival during a time in which the city is free from yellow fever." Further it stressed that "no embarkation from Europe should proceed later than the beginning of May . . . [or] until the end of September."82HNOC, Deutsches Haus Collection 1847–1983 EL 1. 1984 Item 1—Die Deutsche Gesellschaft von New Orleans, Louisiana. 1848–1888.

The data that the DGNO gathered between 1847 and 1860 when juxtaposed against the census figures of 1850 and 1860 explain the settlement patterns of Germans who landed in New Orleans. Of the 233,374 immigrants the society processed, sixty percent boarded steamships upriver upon their arrival. Seventy-five percent of that number chose St. Louis and its surrounding environs as their destination with just over twenty-three percent headed for the Ohio River Valley. The rest set out for Texas and, to a lesser extent, California. The remaining 63,665 were identified as either unsure of their final destination, withheld that information from the society, or had decided to remain in New Orleans for the time being. The society did not track those who migrated after their processing. Given that the German population of Louisiana was 24,614 in 1860—having only grown by 6,727 since 1850—it is safe to assume that the majority of the 63,665 who did not make immediate travel arrangements eventually migrated out of the region. Only five percent of the total German immigration occurred during the peak fever months of July, August, and September and sixty-five percent avoided arriving from the end of May to the first of November.83Ibid.

A girl suffering from yellow fever. Watercolor by unknown creator. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0.

The majority of German immigrants made arrangements in advance of their arrival to settle in areas deemed "healthy." The timing of their arrival suggests that they heeded the settlement literature's advice and almost unanimously avoided New Orleans during peak yellow fever months even in years when the disease was not epidemic. May, the month immediately preceding the yellow fever season, was the third highest month for German immigration to New Orleans. High numbers in November and December could be explained away by the avoidance of frozen rivers in the North, but seeing immigration peak immediately before and after yellow fever season suggests more. An even clearer picture becomes apparent when we combine data from the DGNO and U.S. Census with the gestalt of the geographic recommendations of the settlement literature (see "Mental Map of Yellow Fever" maps).

Cover page of J.W. McClung's Minnesota as it is in 1870, (St. Paul, Minnesota, 1870). Courtesy of the Library of Congress General Collections and Rare Book and Special Collections Division, loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01092/?sp=1.

Yellow fever and antebellum German perceptions of its hold on the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal South contributed significantly to their avoidance of these areas. Kindled by the vast expanse of the Louisiana Purchase, travel and settlement writing as well as the discourse of medical geography contributed to the popularization of scientific knowledge (Wissenschafts-popularisierung). The American frontier provided economic and scientific opportunity to observers and newcomers brimming with new ideas about the relationship between health and the land. The explosion of European immigration to the United States had an immediate and lasting effect, as German and Irish immigrants moved into US cities seeking a better life.

Germans, in particular, sought out the expanse west of the Appalachians and, if the extent of writing presented in this essay is any indication, they were considerably well informed as to the politics, economics, and health of the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal South. This is not to say that they came prepared. With published accounts of an unknown land in mind and far less money and resources than needed, they arrived in New Orleans by the hundreds of thousands: most of them promptly boarded a steamship and traveled up the Mississippi to what they hoped would be healthier country.

About the Author

Paul Michael Warden is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara and a visiting scholar in Harvard's Department of the History of Science. His dissertation focuses on how yellow fever shaped the medical imagination and development of antebellum New Orleans. His broader research examines how ecology and geography intersect with period medical and scientific theory within early American history.

Cover Image Attribution:

Emigration map and guide to North America, Stuttgart, Germany, 1853. Map by Gotthelf Zimmermann, published by J.B. Metzler’schen Buchhandlung. Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.Recommended Resources

Text

Carey, Mark. "Inventing Caribbean Climates: How Science, Medicine and Tourism Changed Tropical Weather from Deadly to Healthy," Osiris 26, no. 1 (2011): 129–130.

Herminghouse, Patricia. "The German Secrets of New Orleans." German Studies Review 27, no. 1 (2004): 1–16.

Humphreys, Margaret. Yellow Fever and the South. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. "Fear of Hot Climates in the Anglo-American Colonial Experience." The William and Mary Quarterly 41, no. 2 (1984): 213–40.

McNeill, J. R. Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Merrill, Ellen C. Germans of Louisiana. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2005.

Nash, Linda. Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999.

Valencius, Conevery Bolton. The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Web

Brink, Susan. "Yellow Fever Timeline: The History Of A Long Misunderstood Disease." National Public Radio. August 28, 2016. http://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/08/28/491471697/yellow-fever-timeline-the-history-of-a-long-misunderstood-disease.

Donato, Katharine and Shirin Hakimzadeh. "The Changing Face of the Gulf Coast: Immigration to Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama." Migration Policy Institute. January 1, 2006. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/changing-face-gulf-coast-immigration-louisiana-mississippi-and-alabama.

"German Settlers in Louisiana and New Orleans." The Historic New Orleans Collection. Accessed February 16, 2017. http://www.hnoc.org/research/sources-study-germans-louisiana-and-new-orleans-williams-research-center.

Kelley, Laura D. "Yellow Fever." In KnowLouisiana, edited by David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. January 16, 2011. http://www.knowlouisiana.org/entry/yellow-fever-in-louisiana.

Public Broadcasting Service. "The Great Fever." American Experience Series. September 29, 2006. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/fever/index.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Carl Leon Bankston, ed., Encyclopedia of American Immigration, vol. 2 (Ipswich, MA: Salem Press, 2010), 476. |

|---|---|

| 2. | For the history of the settlement of Louisiana’s Cotes des Allemandes (the German coast) near New Orleans, see: Ellen C. Merrill, The Germans of Louisiana (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2005). Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth U.S. Census 1860a-04, 2–590; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Seventh U.S. Census 1850a-02, xxxvi. |

| 3. | Johann Friedrich Nonne, eds. Neue Allgemeine Weltbühne Auf Das Jahr 1804, (Erfurt, Germany: Johann Friedrich Nonne, 1804), 499; Thank you to Alexander Cors for encouraging a more suitable translation and for clarifying Nonne’s role in reprinting this piece. |

| 4. | Paul Weber, America in Imaginative German Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1926), 102–103. |

| 5. | “Neueste Colonisations-Schriften,” Ergänzungsblätter zur Jenaischen Jenaischen Allgemeinen Literatur-Zeitung 2, nos. 84–85 (1836): 281–295. |

| 6. | Maria Wagner, ed., Was die Deutschen aus Amerika berichteten, 1828–1865 (Stuttgart, Germany: H. D. Heinz, 1985), x–xi. |

| 7. | Julian Schmidt, Geschichte der deutschen Literatur von Leibniz bis auf unsere Zeit (1896; repr., Charleston, SC: Nabu Press, 2011), 271. |

| 8. | Andreas Daum, Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Jahrhundert: Bürgerliche Kultur, naturwissenschaftliche Bildung und die deutsche Öffentlichkeit (München, Germany: Oldenbourg, 2002). |

| 9. | Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997), 302; Mark Harrison, Contagion: How Commerce Has Spread Disease (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 49. |

| 10. | La Vern J. Rippley, The German Americans (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1976), 44–45. |

| 11. | Conevery Bolton Valenčius, The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (New York: Basic Books, 2002); Linda Nash, Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006). Environmental historians, such as Conevery Bolton Valenčius and Linda Nash, have demonstrated how depictions of the health of the land were invaluable to nineteenth-century settlers in the burgeoning American West. |

| 12. | Both the census of 1850 and 1860 provide population statistics by nation of origin, providing the total number of German-born in each state. Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth U.S. Census 1860a-04, 2–590; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Seventh U.S. Census 1850a-02, xxxvi. |

| 13. | For more on German-Americans and motivations for German-American settlement see: Merill, Germans of Louisiana, 9, 32–40; Walter D. Kamphoefner and Wolfgang Helbich, eds., Germans in the Civil War: The Letters They Wrote Home (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 2–3; Rippley, The German Americans, 51; Andrea Mehrländer, The Germans of Charleston, Richmond and New Orleans during the Civil War Period, 1850-1870 (Berlin, Germany: Degruyter, 2011) 14; Patricia Herminghouse, “The German Secrets of New Orleans,” German Studies Review 27 (February 2004): 1–12; Wagner, Was die Deutschen aus Amerika berichteten, xi–xii. |

| 14. | David Baillie Warden, A Statistical, Political, and Historical Account of the United States of America (Edinburgh, Scotland: Hurst, Robinson, and Company, 1819), 281. |

| 15. | Margaret Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 6–7. Jo Ann Carrigan, The Saffron Scourge: A History of Yellow Fever in Louisiana (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 1994), 10–11; Mariola Espinosa, “The Question of Racial Immunity to Yellow Fever in History and Historiography” Social Science History 38, nos. 3 and 4 (Fall/Winter 2014): 437–454. |

| 16. | David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 25–32. There is a lengthy historiography of racialized climate theory broadly conceived by Europeans in the nineteenth century. The following examples attest to American and European utilization of that theory within the American South: Mark Carey, “Inventing Caribbean Climates: How Science, Medicine and Tourism Changed Tropical Weather from Deadly to Healthy,” Osiris 26, no. 1 (2011): 129–130; A. Cash Koeniger, “Climate and Southern Distinctiveness” Journal of Southern History 54, no. 1 (February 1988): 21–44; and Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, 7. |

| 17. | Cognitive mapping has been utilized by a wide array of fields, but the most influential of these works are arguably those within environmental psychology and city planning. See: R.M. Kitchin, “Cognitive Maps: What are They and Why Study Them,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 14 (1994): 1–19; and Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1960). |

| 18. | Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, 5–6. |

| 19. | Ibid., 18–19; Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 302; Harrison, Contagion, 49. |

| 20. | J. Valentin Hecke, Reise durch die Vereinigten Staaten von Nord-Amerika in den Jahren 1818 und 1819, vol. 1 (Berlin: H. Pb. Petri, 1820), 1. |

| 21. | “Vermischte Schriften,” Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (1821): 785–792. |

| 22. | Ibid., 792. |

| 23. | Hecke, Reise durch die Vereinigten Staaten, vol. 1, 76. |

| 24. | Ibid., 166–67. |

| 25. | Ibid., 167–183. |

| 26. | Ibid., 166–67, 170 |

| 27. | Ibid., 161. |

| 28. | Ibid., 166 |

| 29. | Ibid., 167. |

| 30. | Ibid., 170–171. |

| 31. | Ibid. |

| 32. | Ibid. |

| 33. | Ibid., 171. |

| 34. | Ibid., 170–171. |

| 35. | Ignatz Hülswitt, Tagebuch einer Reise nach den Vereinigten Staaten und der Nordwestküste von Amerika (Münster, Germany: Coppenrathschen Buch und Kunsthandlung, 1828), 306, 308. |

| 36. | Hülswitt, Tagebuch einer Reise nach den Vereinigten Staaten, 305–306. |

| 37. | Ibid., 304. |

| 38. | Neue Allgemeine Geographische und Statistische Ephemeriden, (Weimar, Germany: Geographischen Institut und des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1830) 215. |

| 39. | Peter Littke, “Ignatz Hülswitt, the German ‘John R. Jewitt’ at Nootka Sound?” The Initiative for Russian American History, April 2002, www.irah.eu. |

| 40. | Friedrich Paul Wilhelm, Travels in North America 1822-1824, ed. Robert Nitske and Savoie Lottinville (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), xiii. |

| 41. | Ibid., xv, xiii–xx. |

| 42. | Ibid., 34. |

| 43. | Ibid., 21, 34. |

| 44. | Ibid., 34. |

| 45. | Ibid., 31. |

| 46. | Auszüge aus Briefen aus Nord-Amerika, geschrieben von zweien aus Ulm an der Donau gebürtigen, num in Staate Louisiana ansässigen Geschwistern (Ulm, Germany: E. Nübling Book Printers, 1833), 32–35, 51. |

| 47. | Ibid., foreword. |

| 48. | Ibid., 22–23. |

| 49. | Ibid., 28. |

| 50. | Ibid., 25. |

| 51. | Ibid., 51. |

| 52. | Ibid., 52. |

| 53. | Ibid., 62–63. |

| 54. | Ibid., 148. |

| 55. | Gottfried Duden, Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas (Elberfeld, Germany: S. Lucas, 1829). |

| 56. | Robyn Burnett and Ken Luebbering, German Settlement in Missouri: New Land, Old Ways (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996), 10. |

| 57. | Robert Frizell, Independent Immigrants: A Settlement of Hanoverian Germans in Western Missouri (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 29; Conevery Bolton Valenčius, Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 37; Richard O’Connor, The German-Americans: An Informal History (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1968), 68–70; Rippley, The German-Americans, 44. |

| 58. | Duden, Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas, 165–166, 328. |

| 59. | Ibid., 142–143. |

| 60. | Ibid., 328. |

| 61. | Ibid., 328, 330. |

| 62. | Ibid., 332. |

| 63. | Ibid., ix–xiv, 110. |

| 64. | T.S. Baker, “America as the Political Utopia of Young Germany,” Americana Germanica 1 (1897): 78. |

| 65. | Jack Le Chien, “We Must Make Them Understand Lincoln is Our Man,” ed. Molly McKenzie (Bellville, IL: Koerner House Restoration Committee, 2011), 14. |

| 66. | Gustav Koerner, Beleuchtung des Duden’schen Berichtes über die westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas, von Amerika aus (Frankfurt, Germany: Karl Körner, 1834), 28. |

| 67. | Duden, Bericht über eine Reise nach den westlichen Staaten Nordamerikas, ix–xiv, 110. |

| 68. | Holman Hamilton and James L. Crouthamel, “A Man for Both Parties: Francis J. Grund as a Political Chameleon,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 97 (1973): 465–484. |

| 69. | Francis Grund, Die Amerikaner: in ihren moralischen, politischen, und gesellschaftlichen Verhältnissen (Stuttgart, Germany: J.G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung, 1837), 363. |

| 70. | Schmidt, Versuch über den politischen Zustand der Vereinigten Staaten von Nord Amerika im Jahre 1821, 82. |

| 71. | Ibid., 82. |

| 72. | Ludwig G. Blanc, Handbuch des Wissenswürdigsten aus der Natur und Geschichte der Erde und ihrer Bewohner Vol. 3 (Halle, Germany: C.H. Schwetschke und Sohn, 1837). |

| 73. | Ibid., 471. |

| 74. | Ibid., 454. |

| 75. | Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census 1860a-15 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1864), 621. |

| 76. | Blanc, Handbuch des Wissenswürdigsten, 479–492. |

| 77. | Ross, Die Auswanderers Handbuch, 404. |

| 78. | Gabriel Auguste van der Straten-Ponthoz, Forschungen uber die Lage der Auswanderer in den Vereinigten Staaten von Nord Amerika (Augsburg, Germany: K. Kollman Publisher, 1846), 79–80. |

| 79. | Traugott Braume, Hand- und Reisebuch für Auswanderer und Reisende nach Nord, Mittel, und Süd-Amerika (Bamberg, Germany: Buchner Publishing, 1853), 612–613. |

| 80. | Historic New Orleans Collection (HNOC), Deutsches Haus Collection 1847–1983 EL 1. 1984 Item 1—Die Deutsche Gesellschaft von New Orleans, Louisiana. 1848–1888. |

| 81. | Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz. Inventory: 441, No. 24, 215. www.t-stoffel.de/QUELL/Quellen/An%20alle%20die%20auswandern%20wollen%202.htm. |

| 82. | HNOC, Deutsches Haus Collection 1847–1983 EL 1. 1984 Item 1—Die Deutsche Gesellschaft von New Orleans, Louisiana. 1848–1888. |

| 83. | Ibid. |